Pediatric MRI Urography: Advances in Renal Imaging

Pediatric Magnetic Resonance Urography: Emerging Technologies and the Future of Quantitative Renal Imaging

Benjamin Press1,2 Rachael Germany3, Mariana Coronado3, Andrew Kirsch1,2,3

- Pediatric Urology Department, Emory University School of Medicine.

- Pediatric Urology Department, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta.

- Pediatric Urology Department, Georgia Urology.

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 October 2025

CITATION: PRESS, Benjamin et al. Pediatric Magnetic Resonance Urography: Emerging Technologies and the Future of Quantitative Renal Imaging Benjamin Press 1,2 , Rachael Germany 3 , Mariana Coronado 3 , Andrew. Medical Research Archives, [S.l.], v. 13, n. 10, oct. 2025. Available at: <https://esmed.org/MRA/mra/article/view/6990>.

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i10.6990

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

Magnetic resonance urography (MRU) has evolved over the past three decades into a validated tool for evaluating the pediatric urinary tract. Originally developed in the early 1990s, MRU now combines high-resolution anatomic imaging with quantitative functional assessment, offering a radiation-free alternative to traditional modalities. Comparative studies have consistently demonstrated excellent agreement between MRU-derived differential renal function and radionuclide scintigraphy. Beyond functional equivalence, MRU provides superior delineation of complex anomalies such as megaureter and ectopic ureteral insertion, directly informing surgical planning. Recent innovations have enhanced feasibility in younger children, with real-time imaging and compressed sensing reducing scan times by 30–50% and improving motion robustness. Multiparametric protocols integrating diffusion and perfusion sequences, as well as emerging multi-nuclear approaches, extend MRU’s role into parenchymal and physiologic evaluation. Collectively, these advances shift MRU from a problem-solving adjunct to a central modality in pediatric urology, with future directions focused on standardization, multicenter validation, and potential integration of artificial intelligence for quantitative analysis.

Keywords

Magnetic Resonance Urography, Pediatric Urology, Quantitative Renal Function, Urinary Tract Anomalies, Diffusion and Perfusion Imaging, Artificial Intelligence in Medical Imaging.

Introduction

Magnetic resonance urography (MRU) has undergone rapid development since its introduction in the early 1990s, when heavily T2-weighted “static-fluid” sequences were first used to non-invasively visualize dilated urinary tracts. By the late 1990s, the technique expanded with contrast-enhanced excretory MRU, allowing assessment of renal perfusion and urinary drainage analogous to intravenous urography. These advances provided the foundation for MRU’s clinical uptake in pediatric urology, where the ability to combine detailed anatomic imaging with functional analysis has been particularly valuable in congenital anomalies of the urinary tract. Several reviews have summarized the clinical uptake and evolving role of MRU in pediatric practice.

Although ultrasound (US), voiding cystourethrography (VCUG), and radionuclide scintigraphy remain integral to the diagnostic algorithm, each modality has inherent limitations. US is operator dependent and lacks functional assessment; VCUG is invasive and restricted to the bladder and urethra; and scintigraphy provides limited anatomic resolution and involves ionizing radiation. MRU addresses these shortcomings by delivering a comprehensive, radiation-free evaluation of both anatomy and function in a single examination.

Validation studies over the past decade have firmly established MRU as a reliable alternative to scintigraphy. Large pediatric series demonstrate correlation coefficients of 0.95–0.99 between MRU-derived differential renal function and radionuclide studies. Beyond functional equivalence, MRU surpasses conventional imaging in delineating complex anomalies such as megaureter and ectopic ureter, where both US and scintigraphy may be inconclusive. Importantly, functional scoring systems based on MRU parameters have been developed to discriminate surgical from non-surgical cases of ureteropelvic junction obstruction, achieving predictive accuracy with reported AUC up to 0.91. Additionally, because MRU permits evaluation of qualitative functional and physiologic parameters, we have shown MRU to be a valuable tool for distinguishing congenital renal dysplasia from renal scarring as well as the pre- and postoperative evaluation of ureteropelvic junction obstruction and pyeloplasty.

Recent technical innovations have further enhanced feasibility in children. Real-time MRI and compressed sensing have reduced scan times by 30–50%, improving motion robustness and decreasing the need for sedation. Optimized 3 T protocols provide superior signal-to-noise ratios, while remaining mindful of artifact susceptibility. Multiparametric MRU now integrates diffusion, perfusion, and functional sequences into unified protocols, and experimental applications of multi-nuclear MRI (23Na, 31P-MRS) extend the modality into physiologic assessment.

Collectively, these developments position MRU not only as a diagnostic adjunct but as a central imaging platform in pediatric urology, with a trajectory toward broader clinical adoption and standardized integration. The objective of this review is to provide a clinically oriented synthesis of MRU. Specifically, we summarize the technical principles relevant to daily practice, compare MRU to conventional imaging modalities within guideline-based diagnostic pathways, and highlight scenarios where MRU directly impacts surgical decision-making. We also review recent technical innovations that improve feasibility in children and discuss emerging applications that may expand MRU’s role in the future. By outlining both current clinical applications and anticipated directions, we aim to clarify MRU’s evolving place in pediatric urology and provide a framework for its broader adoption.

Technical Principles of MRU

MRU can be performed on both 1.5 Tesla (T) and 3 T systems. Higher field strength at 3 T provides an approximately 40–50% improvement in signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), which enhances spatial resolution and allows thinner slices for high-quality 3D reconstructions. This advantage is particularly valuable for evaluating structural complexity such as duplicated systems or ectopic ureteral insertions. Improved SNR also benefits fluid-sensitive T2-weighted sequences when contrast administration is contraindicated. However, 3 T systems are more susceptible to artifacts from surgical hardware, bowel gas, or patient motion, whereas 1.5 T scanners often produce more uniform fields and fewer shading artifacts, especially in larger children.

Static fluid imaging is typically obtained with heavily T2-weighted single-shot techniques such as HASTE or SSFSE, which yield strong contrast between fluid and surrounding tissue. These sequences form the backbone of anatomic MRU, reliably demonstrating hydronephrosis, duplex systems, and perinephric collections. T1-weighted imaging complements this by depicting renal parenchyma, corticomedullary differentiation, and solid lesions. Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) adds sensitivity to tissue abnormalities, with restricted diffusion correlating with acute pyelonephritis, neoplasms, and high-grade obstruction. Three-dimensional acquisitions enable multiplanar reformatting and volume-rendered reconstructions, which are especially helpful for complex abnormalities such as ectopic ureteral insertions and ureteral strictures.

| MRI Sequences | Est Time (min:sec) |

|---|---|

| Localizer | 0:08 |

| HASTE Sagittal FS | 0:16 |

| HASTE Coronal FS | 0:15 |

| T2 Axial HR FS Kidneys | 5:39 |

| Lasix Given | |

| T1 FLAIR FS Coronal | 4:38 |

| 3D T2 Triggered Kidneys/Ureters | 5:00 |

| Increase Sedation | |

| DWI | 2:56 |

| T2 Axial FS Bladder | 2:47 |

| Contrast Injection | |

| 3D Dynamic Coronal | 10:00 |

| Decrease Sedation | |

| 3D GRE Sagittal | 2:50 |

| 3D GRE Coronal | 2:11 |

| PD Axial FS Kidneys | 1:55 |

| TOTAL STUDY TIME* | 39:12 |

*Post-processing time required to complete the analysis and generate the report is not included in this estimate.

Functional MRU (fMRU) is performed with dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) sequences, capturing the arterial, corticomedullary, and excretory phases after gadolinium injection. Quantitative parameters include time-to-peak enhancement, renal output efficiency, and differential renal function (DRF). Validation studies demonstrate strong agreement between MRU and radionuclide scintigraphy, with correlation coefficients of 0.95–0.99 across large pediatric series. In suspected ureteropelvic junction obstruction (UPJO), fMRU derived transit times (mean transit time, calyceal transit time, and renal transit time) accurately differentiate obstructed from non-obstructed systems, with abnormal renal transit time correlating with surgical obstruction in over 90% of cases. Damasio et al. recently introduced a morpho-functional score based on fMRU that predicted surgical intervention with an AUC of 0.91.

Practical considerations remain important in pediatric imaging. Hydration, diuretic administration, and bladder catheterization are often employed to optimize urinary tract distension and drainage. Younger children frequently require sedation, with one large pediatric series reporting anesthesia use in nearly 70% of children under age nine. However, technical innovations are reducing these barriers. Hirsch et al. demonstrated the feasibility of real-time MRI in children, while acceleration techniques such as compressed sensing and parallel imaging have reduced scan times by 30–50% without sacrificing diagnostic accuracy. These advances improve motion robustness and decrease the reliance on sedation.

Beyond conventional approaches, MRU is increasingly applied in multiparametric and physiologic domains. Diffusion and perfusion imaging can be integrated into routine protocols, while experimental multi-nuclear techniques such as 23Na and 31P-MRS enable non-invasive assessment of renal sodium handling and energetics. Together, these developments expand MRU from a primarily anatomic and functional modality into a platform for quantitative renal physiology.

Comparative Effectiveness

Ultrasound is the most widely used modality for evaluating the kidneys and bladder both pre- and postnatally. It is non-invasive, radiation-free, portable, cost-effective, and typically performed without sedation. US provides real-time anatomic detail sufficient for grading hydronephrosis and assessing parenchymal changes such as thinning, echogenicity alterations, or cysts. However, limitations include poor visualization of non-dilated ureters, difficulty characterizing the mid-ureter and ureterovesical junction, and challenges in cases with significant distortion or body habitus. US also provides no functional data, though contrast-enhanced US with microbubble agents may eventually expand its utility for perfusion assessment.

Diuretic renal scintigraphy remains the worldwide standard for functional assessment. MAG3 studies quantify differential DRF and drainage, while DMSA detects cortical defects and scarring, and DTPA evaluates glomerular filtration-based DRF. These studies are reproducible and relatively noninvasive but provide limited anatomic detail and involve ionizing radiation. MRU has also been validated in comparison to DMSA. Cerwinka et al. demonstrated that MRU reliably identified cortical defects and renal scarring in children with vesicoureteral reflux, showing close agreement with DMSA studies while avoiding radiation exposure.

Computed tomography is used sparingly in children, primarily for renal masses and urinary tract stones. While multiphase CT urography is well established in adults, pediatric use is restricted due to radiation concerns. Techniques such as dual-energy CT and split-bolus protocols can reduce exposures but remain impractical in most pediatric settings.

Magnetic resonance urography provides a comprehensive alternative by combining high-resolution anatomic and functional evaluation without radiation exposure. Unlike US, MRU is operator-independent and reliably depicts the entire collecting system. Compared with VCUG, which is invasive and confined to the bladder and urethra, MRU is non-invasive and evaluates the upper and lower urinary tract in continuity. Early work even explored cine MR cystography as a non-invasive alternative to VCUG for reflux evaluation, though this has not achieved widespread clinical adoption. Relative to scintigraphy, MRU provides equivalent or superior functional data while also supplying detailed anatomic information.

Validation studies underscore this equivalence. Kirsch et al., Al-Shaqsi et al., and Gołuch et al. each demonstrated correlation coefficients of 0.95–0.99 between MRU-derived DRF and MAG3 scintigraphy. Al-Shaqsi et al. found less than 10% discrepancy in DRF values, while Gołuch et al. confirmed nearly perfect agreement across a multicenter cohort. Riccabona et al. reported sensitivity of 88.2%, specificity of 96.2%, and accuracy of 91.7% for MRU in children with suspected functional single kidneys, reinforcing MRU’s diagnostic reliability.

MRU also surpasses other modalities for complex anomalies. Świętoń et al. showed MRU to be superior to US and scintigraphy in evaluating primary megaureter, particularly for delineating insertional anatomy and functional obstruction. Similarly, MRU accurately depicts ectopic ureters and duplex systems, which are frequently missed by ultrasound. Taken together, the evidence demonstrates that MRU is not merely equivalent to scintigraphy for functional assessment but superior in many contexts due to its combined structural and quantitative evaluation. This positions MRU as the optimal imaging modality for pediatric hydronephrosis and related anomalies, ensuring accurate diagnosis and guiding effective treatment planning.

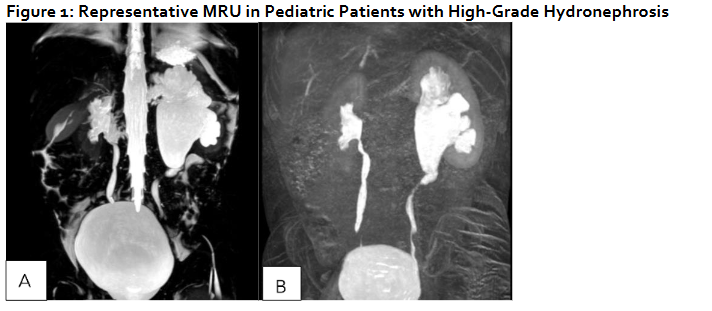

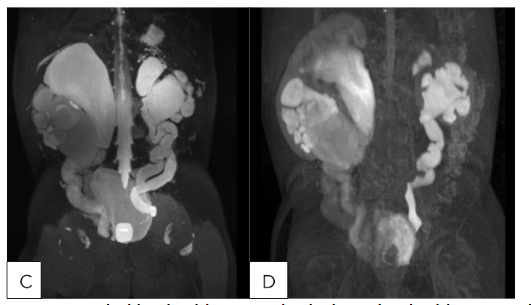

Representative MRU in Pediatric Patients with High-Grade Hydronephrosis

(A,B) 24 month old male with SFU Grade 4 hydronephrosis with UPJ morphology without obstruction/decompensation and (C,D) 23 month old female with bilateral duplex collecting systems with persistent grade 4 hydronephrosis following surgical reconstruction. (A) T2 MIP: Right kidney SFU grade 4, Left kidney SFU grade 1. (B) T1 Gd-enhanced MIP: Renal transit time is 2 minutes 1 seconds on the left, which is normal. Renal transit time is 1 minutes 47 seconds on the right, which is normal. (C): T2 MIP: Duplicated left kidney with cystic dysplasia of the upper left moiety and SFU grade 4 of the lower left moiety, Duplicated right kidney with SFU grade 4 of both upper and lower moieties, Tortuous ureters. (D) T1 Gd-enhanced MIP: Unit Patlak differential renal function is 56.9% on the lower left moiety and 43.1% on the upper left moiety. Renal transit time is 3 minutes 45 seconds on the left lower pole, which is nonobstructive. The left upper pole demonstrates trace contrast excretion. The equivocal range of the renal transit time of the right upper and lower pole is most likely related to capacious system. It does not appear to be high-grade obstruction.

The most widely studied application of MRU in pediatric urology is the evaluation of hydronephrosis and suspected UPJO. Traditional modalities such as ultrasound and scintigraphy provide partial information, but MRU offers the unique ability to combine anatomic detail with quantitative functional analysis. In a prospective comparison, Perez-Brayfield et al. found MRU superior to ultrasound or MAG3 scintigraphy in predicting surgical outcomes in hydronephrosis. Leppert et al. reported that incorporating MRU into the preoperative workup altered surgical decision-making in nearly 30% of children initially assessed by ultrasound and scintigraphy alone. Janssen et al. further refined MRU’s role by demonstrating that the change in renal pelvic diameter after furosemide administration (Δ pelvis) was a sensitive predictor of clinically significant UPJO. Crossing vessels, a frequent confounder in obstruction, are also well evaluated with MRU. Parikh et al. and Weiss et al. demonstrated that MRU reliably identified aberrant vessels compressing the ureteropelvic junction, findings that directly impacted surgical planning.

Quantitative validation has strengthened this role: correlation coefficients for DRF between MRU and scintigraphy consistently range from 0.95 to 0.99, with Gołuch et al. demonstrating nearly perfect agreement in a multicenter pediatric cohort. Al-Shaqsi et al. confirmed <10% discrepancy between MRU- and MAG3-derived DRF, while Riccabona et al. showed sensitivity of 88.2% and specificity of 96.2% for MRU in children with functional single kidneys. Beyond equivalence, MRU-derived transit times reliably differentiate obstructed from non-obstructed systems, with abnormal renal transit time correlating with surgical confirmation of obstruction in >90% of cases. Importantly, Damasio et al. developed a morpho-functional MRU score that predicted surgical intervention with an AUC of 0.91, demonstrating MRU’s potential to guide management rather than simply confirm diagnosis.

In primary megaureter, MRU’s advantages are similarly clear. Świętoń et al. found MRU superior to ultrasound and scintigraphy in delineating ureteral insertion and identifying functionally significant obstruction. In their cohort, MRU correctly identified all obstructed megaureters that ultimately required surgery, whereas ultrasound underestimated both the degree of dilatation and the anatomical level of obstruction in nearly one-third of cases. For equivocal cases on scintigraphy, MRU provided decisive information, highlighting its value as a problem-solving modality.

Duplex kidneys and ectopic ureters also represent domains where MRU outperforms conventional imaging. Avni et al. demonstrated that MRU significantly improved preoperative planning in children with complicated duplex kidneys, especially in characterizing duplicated moieties and their drainage patterns. Joshi et al. added international validation from an Indian cohort, showing comparable accuracy of MRU in duplex systems and reinforcing its generalizability across practice settings. Figueroa et al. confirmed MRU’s role in detecting ectopic ureters, with MRU identifying insertions that were missed on ultrasound. These findings are clinically meaningful, as correct diagnosis of ectopic insertion can alter management from conservative monitoring to definitive ureteral reimplantation.

MRU also plays an important role in post-surgical follow-up. Grattan-Smith et al. highlighted that functional parameters derived from MRU, such as renal output efficiency and time-to-peak enhancement, correlated with symptomatic improvement after pyeloplasty. Arlen et al. showed MRU’s utility in diagnosing ureteral strictures, particularly in children with prior reconstruction where ultrasound findings were inconclusive. By providing a reproducible, radiation-free alternative to scintigraphy, MRU allows longitudinal surveillance of complex surgical patients without cumulative exposure.

Beyond these well-established indications, MRU has contributed to the evaluation of less common anomalies. Garcia-Roig et al. demonstrated its use in prune belly syndrome, where MRU provided detailed evaluation of both dilated and hypoplastic segments of the upper tracts. Kalisvaart et al. reported the advantage of MRU over ultrasound in contralateral kidney assessment in multicystic dysplastic kidney disease. Stone et al. recently described MRU appearances of rare variants of megacalycosis, adding to its role in defining atypical congenital anomalies.

MRU’s ability to provide combined anatomic and functional information in a single, radiation-free examination has increasingly shifted its role from adjunctive to central in diagnosis, prognostication, and post-surgical follow-up.

Recent Advances and Future Directions

The future of magnetic resonance urography (MRU) lies in overcoming its historical limitations and expanding its role from diagnostic adjunct to a central, physiology-based platform in pediatric urology. A major barrier has been the need for sedation, required in up to 70% of children under age nine. Recent technical innovations are directly addressing this challenge. Hirsch et al. demonstrated the feasibility of real-time MRI in children, showing that free-breathing, motion-robust acquisitions could generate diagnostic-quality abdominal images. Kim et al. similarly reported on real-time 3D sequences with encouraging results in motion-prone pediatric patients. Complementary acceleration techniques, including compressed sensing and parallel imaging, reduce acquisition time by 30–50% while maintaining diagnostic accuracy. These approaches not only decrease anesthesia exposure but also lower cost, increase throughput, and expand access to centers without routine pediatric anesthesia support, marking a transition toward sedation-free MRU.

In parallel, advances in post-processing are addressing reproducibility and workflow. MRU analysis has traditionally been labor-intensive and operator-dependent, but automated segmentation and machine learning tools are increasingly capable of extracting functional parameters such as differential renal function and transit times. These methods reduce inter-observer variability and shorten analysis time, while multicenter initiatives are beginning to harmonize acquisition protocols and functional definitions. Standardization is essential for establishing normative pediatric reference ranges, validating predictive metrics, and incorporating MRU into clinical guidelines for hydronephrosis and congenital anomalies.

Beyond workflow, MRU is also expanding into multiparametric and quantitative domains. Diffusion-weighted imaging and perfusion-sensitive sequences provide tissue-level sensitivity to inflammation, ischemia, and obstruction. Radiomics and quantitative texture analysis applied to these data suggest that MRU-derived features could eventually serve as predictive biomarkers, differentiating obstructive from non-obstructive hydronephrosis or identifying kidneys at risk for scarring. This represents a conceptual shift from imaging as a descriptive tool to imaging as a contributor to precision medicine and outcome prediction.

The most forward-looking innovations involve multi-nuclear MRI, which extends MRU beyond proton imaging into physiologic assessment. Sodium (23Na) MRI visualizes corticomedullary sodium gradients, reflecting tubular concentrating ability, while phosphorus (31P) MR spectroscopy measures high-energy phosphate metabolites such as ATP and phosphocreatine, reflecting renal bioenergetics. De Mul et al. recently demonstrated the feasibility of these approaches in pediatric kidneys, suggesting they may detect tubular dysfunction or metabolic stress before structural or functional changes are apparent. Although limited by acquisition times, spatial resolution, and the need for specialized hardware, continued progress in acceleration and motion correction may make these approaches clinically viable within the next decade.

Despite these advances, challenges remain. Gadolinium-based contrast agents, though generally safe, raise concerns about tissue deposition, reinforcing the importance of non-contrast functional methods. Limited scanner availability, high cost, and the need for specialized teams restrict MRU access to tertiary centers, and cost-effectiveness analyses compared with ultrasound and scintigraphy are lacking. Overcoming these barriers will require coordinated multicenter studies, standardized protocols, and integration of patient-centered outcomes into trial design.

Collectively, these innovations point to an expanding role for MRU in pediatric urology. Faster and more robust acquisitions are making sedation-free imaging feasible; automation and standardization are improving reproducibility; multiparametric protocols are creating new biomarkers of renal health; and multi-nuclear imaging offers a vision of MRU as a platform for quantitative renal physiology. Realizing this future will depend on collaboration, validation, and careful integration into clinical pathways, but the trajectory is clear: MRU is poised to evolve from an adjunctive study into a cornerstone of precision diagnostics in pediatric urinary tract disease.

Conclusion

MRU has matured into a reliable and reproducible modality for pediatric urinary tract evaluation. By integrating high-resolution anatomic detail with quantitative functional assessment, MRU addresses the major limitations of ultrasound, voiding cystourethrography, and scintigraphy, while avoiding ionizing radiation. Validation studies demonstrate strong agreement with scintigraphy for differential renal function, and MRU provides added value in complex anomalies such as duplex systems, ectopic ureters, and primary megaureter. Increasingly, MRU is not only diagnostic but prognostic, with morpho-functional scoring systems now able to predict surgical outcomes in ureteropelvic junction obstruction.

Despite these advantages, limitations remain. Scan time, need for sedation in younger children, cost of the MRU scanner, expertise of the radiologist, and variability in acquisition and post-processing across institutions hinder universal adoption. Ongoing technical innovations—real-time imaging, compressed sensing, and artificial intelligence—are reducing these barriers, while multiparametric and multi-nuclear MR approaches point toward an expanded role in renal physiology. Standardization of protocols and multicenter collaboration will be essential to establish normative data, refine predictive models, and integrate MRU into clinical guidelines.

MRU has evolved from an adjunctive tool to a central imaging platform in pediatric urology. Its trajectory is toward broader clinical integration, where it may ultimately serve not only as a diagnostic modality but as a quantitative, physiology-based assessment of the developing urinary tract.

Conflict of Interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Statement:

No financial disclosure.

Acknowledgements:

No acknowledgements.

References:

- Borthne A, Nordshus T, Reiseter T, et al. MR urography: the future gold standard in paediatric urogenital imaging? Pediatr Radiol. Sep 1999;29(9):694-701. doi:10.1007/s002470050677

- Borthne A, Pierre-Jerome C, Nordshus T, Reiseter T. MR urography in children: current status and future development. European radiology. 2000;10(3):503-11. doi:10.1007/s003300050085

- El-Nahas AR, Abou El-Ghar ME, Refae HF, Gad HM, El-Diasty TA. Magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of pelvi-ureteric junction obstruction: an all-in-one approach. BJU international. Mar 2007;99(3):641-5. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06673.x

- Leppert A, Nadalin S, Schirg E, et al. Impact of magnetic resonance urography on preoperative diagnostic workup in children affected by hydronephrosis: should IVU be replaced? Journal of pediatric surgery. Oct 2002;37(10):1441-5. doi:10.1053/jpsu.2002.35408

- Cerwinka WH, Damien Grattan-Smith J, Kirsch AJ. Magnetic resonance urography in pediatric urology. Journal of pediatric urology. Feb 2008;4(1):74-82; quiz 82-3. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2007.08.007

- Grattan-Smith JD, Little SB, Jones RA. MR urography evaluation of obstructive uropathy. Pediatr Radiol. Jan 2008;38 Suppl 1:S49-69. doi:10.1007/s00247-007-0667-y

- Kirsch AJ, McMann LP, Jones RA, Smith EA, Scherz HC, Grattan-Smith JD. Magnetic resonance urography for evaluating outcomes after pediatric pyeloplasty. The Journal of urology. Oct 2006;176(4 Pt 2):1755-61. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2006.03.115

- Chua ME, Ming JM, Farhat WA. Magnetic resonance urography in the pediatric population: a clinical perspective. Pediatric Radiology. 2016/05/01 2016;46(6):791-795. doi:10.1007/s00247-016-3577-z

- Morin CE, McBee MP, Trout AT, Reddy PP, Dillman JR. Use of MR Urography in Pediatric Patients. Current Urology Reports. 2018/09/11 2018;19(11):93. doi:10.1007/s11934-018-0843-7

- Nguyen HT, Herndon CD, Cooper C, et al. The Society for Fetal Urology consensus statement on the evaluation and management of antenatal hydronephrosis. Journal of pediatric urology. Jun 2010;6(3):212-31. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2010.02.205

- Dillman JR, Trout AT, Smith EA. MR urography in children and adolescents: techniques and clinical applications. Abdominal Radiology. 2016/06/01 2016;41(6):1007-1019. doi:10.1007/s00261-016-0669-z

- Emad-Eldin S, Abdelaziz O, El-Diasty TA. Diagnostic value of combined static-excretory MR Urography in children with hydronephrosis. Journal of advanced research. Mar 2015;6(2):145-53. doi:10.1016/j.jare.2014.01.008

- Al-Shaqsi Y, Peycelon M, Paye-Jaouen A. Evaluating pediatric ureteropelvic junction obstruction: Dynamic MR urography vs renal scintigraphy with 99m-technetium mercaptoacetyltriglycine. World J Radiol. 2024;16(3):49-57.

- Gołuch M, Pytlewska A, Sarnecki J. Evaluation of differential renal function in children: a comparative study between magnetic resonance urography and dynamic renal scintigraphy. BMC Pediatr. 2024;24:213. doi:10.1186/s12887-024-04694-2

- Kirsch H, Krüger P, John-Kroegel U. Functional MR urography in children—update 2023. Fortschr Röntgenstr. 2023;195:1097-1105. doi:10.1055/a-2099-5907

- Avni FE, Nicaise N, Hall M, et al. The role of MR imaging for the assessment of complicated duplex kidneys in children: preliminary report. Pediatr Radiol. Apr 2001;31(4):215-23. doi:10.1007/s002470100439

- Figueroa VH, Chavhan GB, Oudjhane K, Farhat W. Utility of MR urography in children suspected of having ectopic ureter. Pediatr Radiol. Aug 2014;44(8):956-62. doi:10.1007/s00247-014-2905-4

- Świętoń D, Grzywińska M, Czarniak P, et al. The Emerging Role of MR Urography in Imaging Megaureters in Children. Front Pediatr. 2022;10:839128. doi:10.3389/fped.2022.839128

- Damasio MB, Rinaldi VE, Magni C. Functional MR urography in children—development of a morpho-functional score to differentiate surgical from non-surgical UPJO kidneys. Front Pediatr. 2022;10:882892. doi:10.3389/fped.2022.882892

- McMann LP, Kirsch AJ, Scherz HC, et al. Magnetic resonance urography in the evaluation of prenatally diagnosed hydronephrosis and renal dysgenesis. The Journal of urology. Oct 2006;176(4 Pt 2):1786-92. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2006.05.025

- Gallo-Bernal S, Bedoya MA, Gee MS, Jaimes C. Pediatric magnetic resonance imaging: faster is better. Pediatric Radiology. 2023/06/01 2023;53(7):1270-1284. doi:10.1007/s00247-022-05529-x

- Hirsch FW, Frahm J, Sorge I, Roth C, Voit D, Gräfe D. Real-time magnetic resonance imaging in pediatric radiology — new approach to movement and moving children. Pediatric Radiology. 2021/05/01 2021;51(5):840-846. doi:10.1007/s00247-020-04828-5

- Vosshenrich J, Koerzdoerfer G, Fritz J. Modern acceleration in musculoskeletal MRI: applications, implications, and challenges. Skeletal Radiology. 2024/09/01 2024;53(9):1799-1813. doi:10.1007/s00256-024-04634-2

- Grzywińska M, Świętoń D, Sabisz A, Piskunowicz M. Functional Magnetic Resonance Urography in Children-Tips and Pitfalls. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). May 18 2023;13(10)doi:10.3390/diagnostics13101786

- Karajgikar JA, Bagga B, Krishna S, Schieda N, Taffel MT. Multiparametric MR urography: state of the art. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2025;45(4):e240151. doi:10.1148/rg.240151

- De Mul A, Schleef M, Filler G, McIntyre C, Lemoine S. In vivo assessment of pediatric kidney function using multi-parametric and multi-nuclear functional magnetic resonance imaging: Challenges, perspectives, and clinical applications. Pediatr Nephrol. 2025;40(8):1539-1548. doi:10.1007/s00467-024-06560-w

- Adler B. Pediatric radiology: practical imaging evaluation of infants and children (1st edn), by Edward Lee (ed). Pediatric Radiology. 2017;48:449-450.

- Gourtsoyiannis NC, Aschoff P. Clinical MRI of the abdomen: why, how, when. Springer; 2011.

- Dickerson EC, Dillman JR, Smith EA, DiPietro MA, Lebowitz RL, Darge K. Pediatric MR Urography: Indications, Techniques, and Approach to Review. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. Jul-Aug 2015;35(4):1208-30. doi:10.1148/rg.2015140223

- Boss A, Martirosian P, Fuchs J, et al. Dynamic MR urography in children with uropathic disease with a combined 2D and 3D acquisition protocol–comparison with MAG3 scintigraphy. The British journal of radiology. Dec 2014;87(1044):20140426. doi:10.1259/bjr.20140426

- Cerwinka WH, Grattan-Smith JD, Jones RA, et al. Comparison of magnetic resonance urography to dimercaptosuccinic acid scan for the identification of renal parenchyma defects in children with vesicoureteral reflux. Journal of pediatric urology. Apr 2014;10(2):344-51. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2013.09.016

- Vasanawala SS, Kennedy WA, Ganguly A, et al. MR voiding cystography for evaluation of vesicoureteral reflux. AJR American journal of roentgenology. May 2009;192(5):W206-11. doi:10.2214/ajr.08.1251

- Gupta RK, Kapoor R, Poptani H, Rastogi H, Gujral RB. Cine MR voiding cystourethrogram in adult normal males. Magnetic resonance imaging. 1992;10(6):881-5. doi:10.1016/0730-725x(92)90441-2

- Riccabona M, Ruppert-Kohlmayr A, Ring E, Maier C, Lusuardi L, Riccabona M. Potential impact of pediatric MR urography on the imaging algorithm in patients with a functional single kidney. AJR American journal of roentgenology. Sep 2004;183(3):795-800. doi:10.2214/ajr.183.3.1830795

- Perez-Brayfield MR, Kirsch AJ, Jones RA, Grattan-Smith JD. A prospective study comparing ultrasound, nuclear scintigraphy and dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of hydronephrosis. The Journal of urology. Oct 2003;170(4 Pt 1):1330-4. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000086775.66329.00

- Janssen KM, Cho JY, Stone K, Kirsch AJ, Linam LE. Decreased percent change in renal pelvis diameter on diuretic functional magnetic resonance urography following administration of furosemide may help characterize unilateral uretero-pelvic junction obstruction. Journal of pediatric urology. Dec 2023;19(6):779.e1-779.e5. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2023.08.014

- Parikh KR, Hammer MR, Kraft KH, Ivančić V, Smith EA, Dillman JR. Pediatric ureteropelvic junction obstruction: can magnetic resonance urography identify crossing vessels? Pediatr Radiol. Nov 2015;45(12):1788-95. doi:10.1007/s00247-015-3412-y

- Weiss DA, Kadakia S, Kurzweil R, Srinivasan AK, Darge K, Shukla AR. Detection of crossing vessels in pediatric ureteropelvic junction obstruction: Clinical patterns and imaging findings. Journal of pediatric urology. Aug 2015;11(4):173.e1-5. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2015.04.017

- Joshi MP, Shah HS, Parelkar SV, Agrawal AA, Sanghvi B. Role of magnetic resonance urography in diagnosis of duplex renal system: Our initial experience at a tertiary care institute. Indian journal of urology : IJU : journal of the Urological Society of India. Jan 2009;25(1):52-5. doi:10.4103/0970-1591.45537

- Arlen AM, Kirsch AJ, Cuda SP, et al. Magnetic resonance urography for diagnosis of pediatric ureteral stricture. Journal of pediatric urology. Oct 2014;10(5):792-8. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2014.01.004

- Garcia-Roig ML, Grattan-Smith JD, Arlen AM, Smith EA, Kirsch AJ. Detailed evaluation of the upper urinary tract in patients with prune belly syndrome using magnetic resonance urography. Journal of pediatric urology. Apr 2016;12(2):122.e1-7. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2015.11.008

- Kalisvaart J, Bootwala Y, Poonawala H, et al. Comparison of ultrasound and magnetic resonance urography for evaluation of contralateral kidney in patients with multicystic dysplastic kidney disease. The Journal of urology. Sep 2011;186(3):1059-64. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2011.04.105

- Stone KM, Cho J, Linam LE, Kirsch AJ. Unique Variants of Megacalycosis on Magnetic Resonance Urography. Urology. Dec 2024;194:189-195. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2024.08.003

- Kim T, Park JC, Gach HM, Chun J, Mutic S. Technical Note: Real-time 3D MRI in the presence of motion for MRI-guided radiotherapy: 3D Dynamic keyhole imaging with super-resolution. Medical Physics. 2019;46(10):4631-4638. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/mp.13748

- Press B, Cho J, Kirsch A. Magnetic Resonance Urogram in Pediatric Urology: a Comprehensive Review of Applications and Advances. International braz j urol : official journal of the Brazilian Society of Urology. May-Jun 2025;51(3)doi:10.1590/s1677-5538.Ibju.2025.004