Advanced Pulmonary Sarcoidosis: Insights from India Study

Advanced Pulmonary Sarcoidosis in India: a single centre experience in North India

Pallav Bhattacharyya1, Deepak Prajapat2, Kanishka Kumar2, Dhruv Talwar3, Saurabh Pahuja4, Anupam Prakash2, Deepak Talwar2,

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 January 2024

CITATION: BHATTACHARYYA, Pallav et al. Advanced Pulmonary Sarcoidosis in India: a single centre experience in North India. Medical Research Archives, [S.l.], v. 13, n. 1, jan. 2025. Available at: <https://esmed.org/MRA/mra/article/view/6269>.

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i1.6269

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Background. Advanced sarcoidosis is a recently defined entity which needs to be elaborated in different geographical areas.

Methods. Retrospective analysis of records in a single north Indian centre is done on patients of advanced sarcoidosis.

Results. The disease was more common in females, non smokers, with mean age 55.91 ± 10.64 years and mean BMI of 28.05 ± 4.26 kg/m2. Majority patients were homemakers. Most common comorbidity was hypertension. Dyspnoea and fatigue were present in all. Radiologically, Scadding stage 4 was most common (70.27%). Septal thickening (100%), ground glass opacity (97.3%), traction bronchiectasis (75.68%) and nodules (70.27%) were typically present on HRCT chest. Lymph node station 7 was most frequently involved (97.3%), and cluster involvement of station 4,7,10 was the commonest (32.4%). Most common PET positive parenchymal entity was nodules (40%), followed by GGO (35%). Most common PET positive extra mediastinal lymph node was gastrohepatic (25%), and extra thoracic organ was salivary glands and spleen. Echo revealed pulmonary hypertension in almost half of patients. Diagnostic yield of non caseating granuloma was highest in TBLB (83.33%) followed by EBUS (74.28%). As regards lung function, diffusion capacity was reduced in all patients. Spirometry revealed mixed pattern in 43.24%, obstructive pattern in 21.63% and restrictive pattern in 32.43%.

Conclusions. Indian experience is somewhat different from data on available global experience. More studies from different parts of the country are required.

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown aetiology that runs a variable course, affecting different organs in severity and adversity across various ethnic populations worldwide. Fibrosing lung pathology may predominate in some regions, particularly in India, where sarcoid interstitial lung disease (ILD) is more common than idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), leading to imminent loss of function and/or life. This entity has been categorized as “Advanced Pulmonary Sarcoidosis.”(1)

In India, tuberculosis is endemic, with manifestations ranging from mediastinal lymphadenopathy and consolidation to cavities and fibrotic changes in the lungs. Within this “forest” of tuberculosis cases, sarcoidosis represents individual “trees,” relatively rare and often overlooked. Tuberculosis and sarcoidosis closely mimic each other in histopathology, making the distinction between the two diseases critical, especially in the Indian subcontinent. The clinical features between the two may also overlap significantly, underscoring the importance of accurate diagnosis. While sarcoidosis cases exist in the community, they are not as commonly diagnosed, and the subset of advanced sarcoidosis patients is particularly challenging to manage.

Although Valeyre D et al. described advanced sarcoidosis in 2014(2), Baughman and colleagues later refined its definition, including categorical information on organ dysfunction, lung function, imaging features, extreme fatigue, and the use of third-line therapy(3).

The true burden of sarcoidosis in India remains unknown, though several reports and case series have been published(4). Misdiagnosis with tuberculosis often delays appropriate therapy, with patients symptomatic for a mean of six years before diagnosis. Consequently, baseline CT scans frequently reveal a UIP pattern in 30% of cases. Given these challenges, we aimed to investigate the spectrum of advanced pulmonary sarcoidosis and assess the need for timely interventions. This study compiles the experience of a WASOG Sarcoidosis Clinic in India to enhance understanding and improve outcomes in this unique subset of patients.

Materials and Methods

This is retrospective observational study performed at Metro Centre for Respiratory Diseases, in Noida, NCR, India approved by IREB.

INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION CRITERIA

Case records of all patients diagnosed as Sarcoidosis based on ATS/ERS/WASOG were screened for the criteria of Advanced Pulmonary Sarcoidosis(3) as below:

-

FVC < 60% predicted

-

FEV1 < 50% predicted

-

DLCO < 50% predicted

-

More than 25% of chest imaging demonstrating fibrosis using scoring system of Walsh et al

-

Pre capillary pulmonary hypertension

Those who satisfied the criteria were further evaluated to check for exclusion criteria included malignant lesions, other granulomatous diseases, pregnancy, and age younger than 18 years.

Detailed demographic data, medical history, results of physical examination, and several investigational data were noted. The latter comprised the radiological findings of chest x-ray, high resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the chest, and positron emission tomography (PET) CT, lung function studies as spirometry, diffusion capacity, and body plethysmography. The histopathological data from excision biopsy or aspiration from extrapulmonary sites of involvement or bronchoscopic aspiration and transbronchial lung biopsy were collected from records.

Data was entered in MS Excel, coded and analysed in statistical software STATA. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic, clinical, and imaging data. Continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard deviation, while

Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. Comparisons between imaging and PET scan findings were analyzed using inferential statistical methods, including chi-square tests and p-values.

Results

The data of 37 patients who qualified as “advanced sarcoidosis” was collated from records. Out of them, 23 were females (62.2%) and 14 were males (37.8%). The mean age of patients in the study was 55.91 ± 10.64 years and the mean BMI was 28.05 ± 4.26 kg/m².

The common co-morbidities were hypertension (35.1 %), diabetes mellitus (32.4%), hypothyroidism (29.7 %), and coronary artery disease (8.1%), followed by benign hypertrophy prostate in 5.4%, obstructive sleep apnoea in 5.4%. Chronic kidney disease, chronic myeloid leukaemia and rheumatoid arthritis was seen in 2.7% each (n=1). Majority of subjects in the study were never smokers (n=35; 94.6%).

Shortness of breath and fatigue were universal symptoms in all patients (n=37;100%), cough was seen in 36 patients (97.3%). This was followed by joint pain in 4 patients (10.8%), visual changes in 3 patients (8.1%), skin changes and clubbing were seen in 2 patients each (5.4%) while weight loss and parotid swelling were seen in 1 patient each (2.7%).

The majority of our patients (62.2 %, n= 23) were homemakers, followed by office goers (27%, n=10) and businessmen (5.4%, n=2).

Majority of study subjects belong to Scadding stage 4 (n=26; 70.27%) followed by Scadding stage 3 (n=9; 24.3%). There are only two (5.4%) subjects who belong to Scadding stage 2.

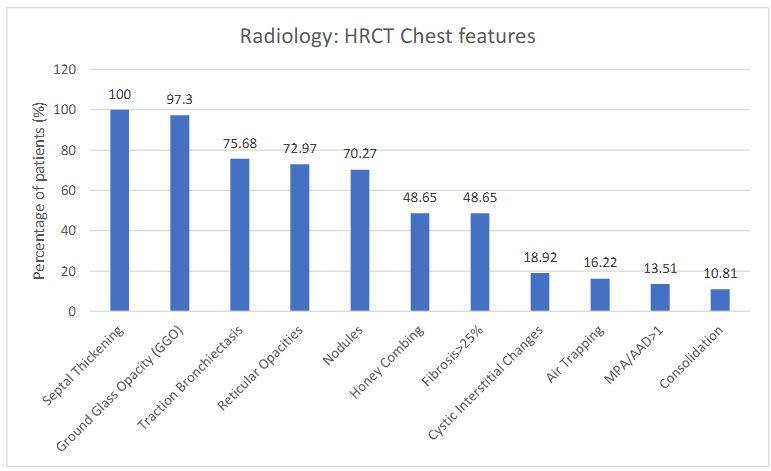

The HRCT chest revealed multiple features with several morphological changes in different frequencies: interlobular septal thickening was seen in 100% followed by ground glass opacity (97.29%), traction bronchiectasis (75.67 %), reticular opacities (72.97%), nodules (70.27%). Honey-combing with UIP pattern was seen as seen 48.6 % in more than 25 % of lungs have been observed in each. The other features noted are macrocytisc interstitial-changes were seen in 18.9%. Ratio of main pulmonary artery to ascending aorta (MPA/AAD) more than one in 13.5% cases. Significant air-trapping was reported in 16.2% cases.

Figure 1 elaborates the various HRCT changes seen in advanced sarcoidosis (n=37)

The common co-morbidities were hypertension (35.1%), diabetes mellitus (32.4%), hyperlipidemia (18.9%) and hypothyroidism (16.2%). The majority of our patients (62.2%, n= 23) were female, followed by males (27%, n= 10) and businessmen (5.4%).

The majority of patients were classified into Scadding stage 2 (n= 10; 27.0%) followed by Scadding stage 3 (n= 8; 21.6%).

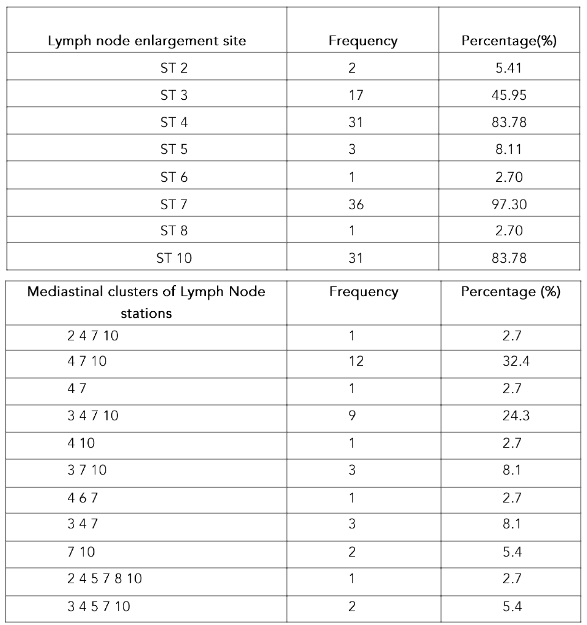

The lymph-node affection site and clusters are displayed in table-1. The most common LN stations involved in combination were 4, 7 and 10 in 32% with add on station 3 in 24%. Isolated mediastinal LN station enlargement as well as station 9 nodes were not seen in any case.

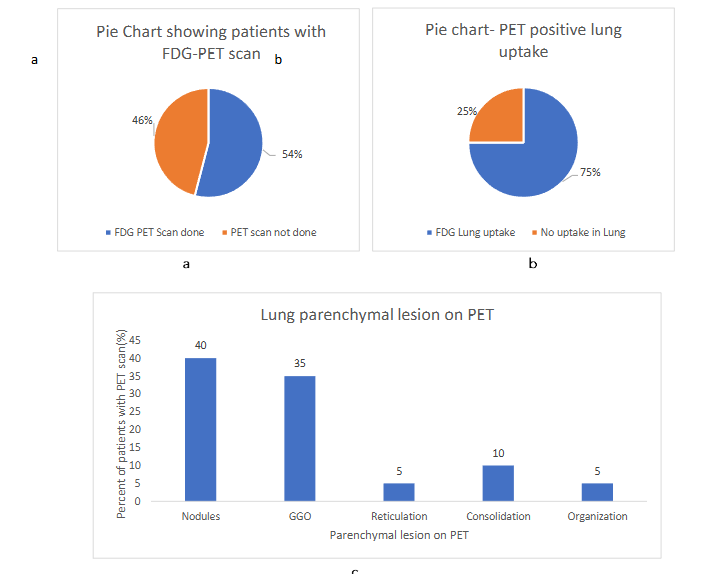

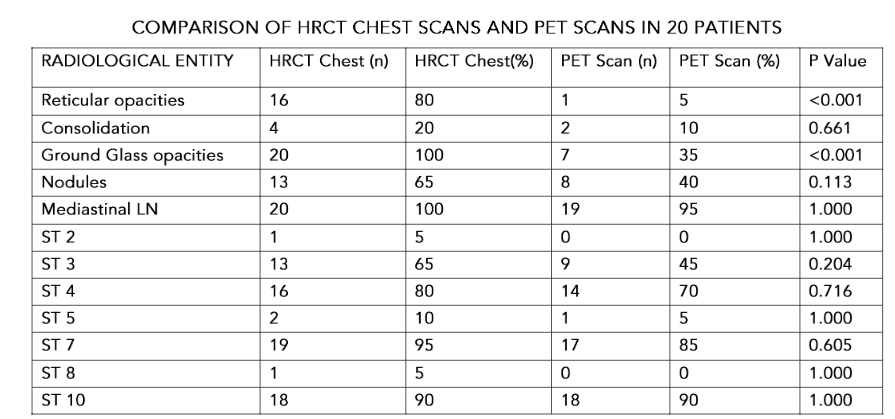

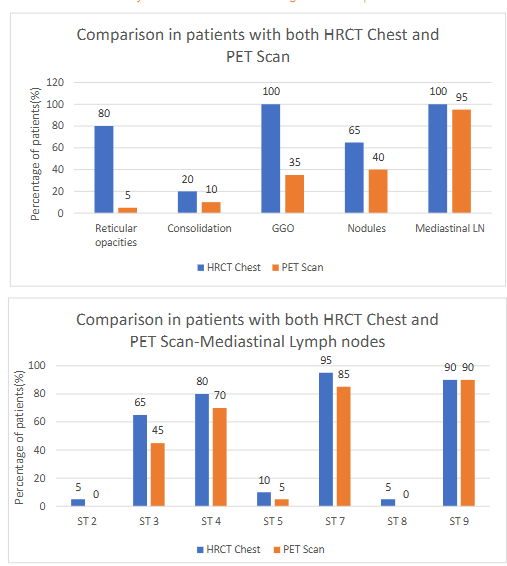

The FDG-PET (fluoro-deoxy-glucose positron emission tomography) scan was done in 20 patients (out of 37) and showed increased uptake in lung parenchyma, different lymph nodes, and organs. The lung parenchymal uptake (75%) was seen most commonly in nodules in (n=8; 40%) followed by ground glass opacities in (n=7; 35%), consolidation, reticulation and organization.

Figure-2 (a, b, c); the figure 2a and 2b are displaying the percentage of patients with PET being done and percentage of lung parenchymal uptake while figure 2c shows the status of different PET positive parenchymal lesions.

FDG-PET scan was done in 40% of patients and the lung parenchymal uptake was noted in 54% (n= 7; 35%), consolidation, reticulation and organization in 10%.

The extra-mediastinal lymph node PET uptake was noticed in gastrohepatic (25%), portocaval in (20%) as well as axillary, supraclavicular, internal mammary, anterior diaphragmatic and inguinal nodes in 10% each cases (see table-2).

Table-2 shows the different group of extra mediastinal lymph nodes with PET uptake.

| Extra-mediastinal LN | Frequency | Percentage % |

|---|---|---|

| Gastrohepatic | 5 | 25 |

| Portocaval | 4 | 20 |

| Axillary | 2 | 10 |

| Supraclavicular | 2 | 10 |

| Internal Mammary | 2 | 10 |

| Anterior Diaphragmatic | 2 | 10 |

| Inguinal | 2 | 10 |

| Infraclavicular | 1 | 5 |

| Epiphrenic | 1 | 5 |

| Retrocrural | 1 | 5 |

| Renal hilar | 1 | 5 |

| Peripancreatic | 1 | 5 |

| Pelvic | 1 | 5 |

PET scan also showed FDG uptake in salivary glands and spleen in 15% each respectively. Other organs with PET positive lesions were reported in liver, maxillary sinuses, antro-pylorus and bone marrow.

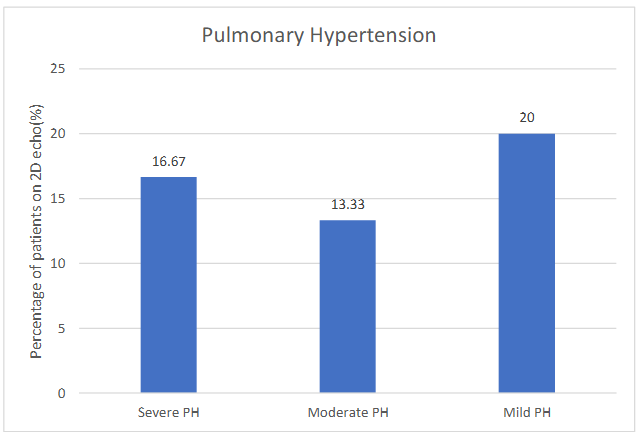

Echocardiography (two dimensional) were done in all patients and showed normal mean ejection fraction (56.36 ± 5.36%) of left ventricle. Pulmonary hypertension (PH) was present in 50% of cases as mild (20%; n=6), moderate (13.33%; n=4), and severe (16.67%; n=5) study subjects respectively.

Figure 3. Bar graph showing severity of pulmonary hypertension in study subjects.

LVDD (Left Ventricular Diastolic Dysfunction) and RWMA (Regional wall motion abnormality) seen in 13.33% (n=4) each. Dilated right ventricle was present in (n=3) 10% of study subjects on 2Dechoardiography.

EBUS (endobronchial ultrasound) biopsy was done in 35 (94.59%), EBB (endobronchial biopsy) in 15 (40.54%), and TBLB (transbronchial lung biopsy) in 12 (37%) of the study subjects. The yield has been compiled in table-3.

Table 3 showing histopathological results of various biopsy procedures

| NCG (non caseating granuloma) | NSI (nonspecific inflammation) | OP (organizing pneumonia) | RL (reactive lymphadenitis) | NG (no granuloma) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBUS (94.59%, n=35) | 74.28% | 5.71% | 2.86% | 14.29% | 2.86% |

| EBB (40.54%, n=15) | 26.67% | 40% | — | — | 33.33% |

| TBLB (37%, n=12) | 83.33% | 16.67% | — | — | — |

The analysis of the treatment offered to patients revealed that steroids were administered in 97.3% of patients followed by hydroxychloroquine in 45.9% and anti-fibrotics in 29.7% of patients. Infliximab was administered in 16.2% (n=6).

The reduction in diffusion capacity (DLCO) was universal; it was severe in 56.76%, very severe in 5.40% and moderate in 37.84% of patients.

Spirometry patterns showed mixed defect to be most common (43.24%) followed by obstructive (21.63%) and restrictive (32.43%) patterns (see table 4).

Table 4 showing spirometry patterns among study subjects

| Spirometry pattern | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Obstructive | 8 | 21.63% |

| Restrictive | 12 | 32.43% |

| Mixed | 16 | 43.24% |

| Normal | 1 | 2.7% |

Table 5. Elaboration of mean spirometry and lung volumes in study subjects

| Obstructive | Restrictive | Mixed | Over-all | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEV1/FVC Pre BD (Absolute Value) | 56.215 | 80.074 | 81.16 | 75.06 |

| Post BD | 52.985 | 81.432 | 83.01 | 75.59 |

| FEV1 Post BD (Absolute Value) | 1.0262 | 1.717 | 0.965 | 1.26 |

| Post BD (%) | 45.62 | 68.25 | 45.12 | 53.7 |

| Absolute change (FEV1) | 0.006 | 0.07 | 0.05 | |

| Percentage Change (FEV1)(%) | 0.37 | 1.84 | 1.94 | |

| FVC Post BD (Absolute Value) | 1.968 | 2.106 | 1.198 | 1.72 |

| Post BD (%) | 68.62 | 70.33 | 46.25 | 59.91 |

| Absolute change (FVC) | 0.138 | 0.047 | 0.027 | |

| Percentage Change (FVC)(%) | 4.75 | 1.33 | 1.07 | |

| TLC Absolute value | 5.2 | 3.128 | 2.69 | 3.46 |

| Percentage (%) | 104.5 | 62.83 | 58.37 | 70.48 |

| RV Absolute value | 3.35 | 1.0583 | 1.54 | 1.80 |

| Percentage (%) | 178.25 | 60.16 | 87 | 98.38 |

| RV/TLC Absolute value | 63.45 | 35.03 | 57 | 50.57 |

| Percentage (%) | 167.5 | 97 | 152.86 | 135.94 |

Discussion

Our observation finds 62.2% females and 37.8% males in advanced sarcoidosis cases. This female predilection was observed in other studies(5). Our study showed mean age of patients to be 55.91 ± 10.64 years. Prior Indian study by Kumar et al(6) showed average age to be 43 years.

Mean BMI was 28.05 ± 4.26 kg/m². A higher BMI showed an increased frequency of sarcoidosis in prior studies.(7) Hypertension and diabetes mellitus was found relatively more frequent (35.1% and 32.4%) in our series compared to other studies.(8). Non smokers are in majority in our experience which matches results of a prior case control study.(9)

We observed shortness of breath and fatigue as universal symptoms, followed by cough unlike others who documented fatigue, shortness of breath, arthalgia and myalgia in decreasing order.(10)

Homemakers were the most common occupation. Prior study points out greater risk of sarcoidosis in occupations such as metal working and transport industry.(11)

Majority of patients belonged to Scadding stage 4 (70.27%) and stage 3 (24.3%). An Indian observation Sharma et al(12) revealed the frequency of stage 1, stage 2, stage 3 as 31%, 26.8% and 55% respectively.

HRCT chest findings revealed the most common mediastinal lymph node involvement to be subcarinal (97.3%). Right lower paratracheal and hilar stations were involved in 83.78% each. The commonest cluster was found to be ST-4,7,10 (32.4%), followed by ST 3,4,7,10 (24.9%). Prior literature reveals most common pattern of lymph node involvement to be stations 4R and 10(13). Paratracheal, subcarinal and hilar nodes involvement have been found in over 90% of subjects(14).

In our experience we have observed septal thickening (100%), ground glass opacity (97.3%), traction bronchiectasis (75.67%), reticular opacities (72.97%), nodules (70.27%), honey combing (> 48.64%), fibrosis > 25% in (48.64%), cystic changes (18.91%). Prior studies show micronodules in up to 75 to 90% of cases.(15) Abehssera et al found bronchial distortion in 47%, linear opacities in 24% and honey combing in 29% of cases.(16) A study by Kristyn Sayball et al(17) showed 26 out of 78 African American patients and 1 out of 19 caucasians had GGO. In our study, GGO was present in 98% of the study subjects.

In our experience with 20 patients in whom PET CT scan was done, lung parenchymal PET uptake was seen in 15 (75%). Out of 15 patients who had pulmonary PET positive lesions, 4 (26.66%) showed extrathoracic uptake. Out of 5 patients without any pulmonary PET uptake, 2 (40%) had extra thoracic PET uptake. It is worthwhile to find that although nodules are present in 70.24 % in HRCT chest scan, showed 26 out of 27 patients had GGO. Study by Mostard et al(18) shows 35 % PET uptake while the HRCT presence was in tune of 97.3 %. The difference in frequency of PET uptake and HRCT findings in our series, however, has similar PET positivity (about 10 %). This observation suggests that different lung morphological lesions express different degree of activity in advanced sarcoidosis.

Mostard et al(18) reviewed 106 sarcoidosis patients and found 59% of them to have PET-uptake in different kinds of pathological lung parenchymal descriptions. The HRCT chest pattern corresponding to most intense FDG uptake were consolidations (48%), lymph nodes (25%), nodules (25%).

Our study revealed gastro hepatic and portocaval are most common extrathoracic lymph node uptake sites. Spleen and salivary glands had 15% involvement each. Liver, maxillary sinus, bone marrow showed uptake in lower frequency (5% each). Study by Mostard et al(18) revealed 73% (n=65) had some positive uptake on PET CT and the uptake was localized in peripheral lymph nodes (n=48), bone (n=14), spleen (n=11), muscle (n=10), Liver (n=6).

In our study, severe PH was seen found less frequently (16.67%) than mild and moderate PH.

Sarcoidosis associated Pulmonary hypertension has been found to be present in 5–20% of patients in sarcoidosis clinics(19). The prevalence of Tricuspid regurgitation has been around 33% in our observation. Prior study by Devraj et al(20) documented tricuspid regurgitation in 85% of patients.

The non-caseating granuloma was detected in 74.24 %, 26.67%, and 83.33% by EBUS-biopsy, EBB and TBLB (see table 3 ). A comparative study with 154 subjects from literature shows demonstration of granuloma in 127 (84.2%) of 151 subjects in whom final diagnosis was established. The diagnostic yield was 68.7%, 49.6%, 22.43%, and 57.1%, respectively for TBLB, EBB, TBNA, and EBUS-TBNA respectively(21). Another work revealed the diagnostic rates for TBNA, TBLB as 88.5%-55.6% respectively; incidentally, granulomas were found most commonly in TBNA from lymph nodes and the authors found that the diagnostic positivity of TBNA was 100 %, same as that of surgical biopsy.(22)

In our study, 21.63% patients had airflow obstruction, 32.43% and 43.24% of patients had restrictive and mixed defect. It is found that for obstructive changes, the mean post bronchodilator FEV1 was 45.60 % and for restrictive changes, the mean FVC (post bronchodilator) was 70.33 % suggesting relatively more severity for obstruction than restriction. The mean FEV1 and FVC for the mixed changes were 45.12, and 45.18 percent respectively.

Calaras D et al(23) has observed 14 (9.7%) patients to have obstructive disease (FEV1/FVC <0.7) in 144 sarcoidosis patients. However, if the criteria for airflow obstruction is changed to FEV1/FVC < 0.8, the frequency of airflow obstruction increased to 56 (38 %). On assessment of the lung volumes, 13 (9%) of the patients had low TLC suggesting restrictive pattern. Obstructive indices like RV/TLC were also found elevated in 13 patients (9%). In another study, the majority of the patients of sarcoidosis showed an FEV1/FVC ratio below 75%. Some of the patients also showed a low peak expiratory flow suggesting the narrowing of the large airways.(24)

In our experience, reduction of diffusion capacity was universal; the majority of subjects with advanced sarcoidosis had either severe or very severe 56.76%, 5.4%; (n=21 ,n=2) diffusion defects. In the series studied by Calaras D et al(23), diffusion defect was present in 69.4% and it was mostly mild (between 60–80%) in 54.1 %, moderate defect (between 40–59%) in 13.9% and severe defect (<40%) in 1.4% (n=2).

Conclusion

Our study highlights key differences in advanced sarcoidosis presentation in India, as compared to global data, including varied HRCT patterns with higher prevalence of septal thickening, ground glass opacities, and traction bronchiectasis, and a mismatch with PET-CT uptake. PET-CT revealed active uptake across lesion types and distinct extrathoracic involvement, particularly in gastrohepatic lymph nodes. Pulmonary testing findings also emphasize the importance of PET-CT in assessing disease activity and guiding diagnostic and management strategies for the Indian population.

Conflict of Interest:

None

Acknowledgements:

None

References

1. Patterson KC, Strek ME. Pulmonary fibrosis in sarcoidosis. Clinical features and outcomes. Ann

Am Thorac Soc. 2013 Aug;10(4):362–70

2. Valeyre D, Nunes H, Bernaudin JF. Advanced pulmonary sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2014

Sep;20(5):488–95

3. Baughman RP, Wells A. Advanced sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2019 Sep;25(5):497–504

4. Sharma SK, Mohan A. Sarcoidosis in India: not so rare. Journal, Indian Academy of Clinical

Medicine. 2004;5(1):12–21.

5. Baughman RP, Field S, Costabel U, Crystal RG, Culver DA, Drent M, et al. Sarcoidosis in America. Analysis Based on Health Care Use. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016 Aug;13(8):1244–52

6. Kumar R, Goel N, Gaur SN. Sarcoidosis in north Indian population: a retrospective study. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2012 Jun;54(2):99–104.

7. Cozier YC, Coogan PF, Govender P, Berman JS, Palmer JR, Rosenberg L. Obesity and weight gain in relation to incidence of sarcoidosis in US black women: data from the Black Women’s Health Study. Chest. 2015 Apr;147(4):1086–93.

8. Martusewicz-Boros MM, Boros PW, Wiatr E, Roszkowski-Śliż K. What comorbidities accompany sarcoidosis? A large cohort (n=1779) patients analysis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2015 Jul 22;32(2):115–20

9. Douglas JG, Middleton WG, Gaddie J, Petrie GR, Choo-Kang YF, Prescott RJ, et al. Sarcoidosis: a disorder commoner in non-smokers? Thorax. 1986 Oct;41(10):787–91.

10. Wirnsberger RM, de Vries J, Wouters EF, Drent M. Clinical presentation of sarcoidosis in The Netherlands an epidemiological study. Neth J Med. 1998 Aug;53(2):53–60.

11. Kucera GP, Rybicki BA, Kirkey KL, Coon SW, Major ML, Maliarik MJ, et al. Occupational risk factors for sarcoidosis in African-American siblings. Chest. 2003 May;123(5):1527–35.

12. Sharma R, Guleria R, Mohan A, Das C. Scadding Criteria for Diagnosis of Sarcoidosis: Is There A Need For Change? CHEST. 2004 Oct 1; 126(4):754S

13. Lynch JP, Kazerooni EA, Gay SE. Pulmonary sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 1997 Dec;18(4):755–

85.

14. Ors F, Gumus S, Aydogan M, Sari S, Verim S, Deniz O. HRCT findings of pulmonary sarcoidosis; relation to pulmonary function tests. Multidisciplinary Respiratory Medicine. 2013 Feb 5;8(1):8.

15. Nakatsu M, Hatabu H, Morikawa K, Uematsu H, Ohno Y, Nishimura K, et al. Large coalescent parenchymal nodules in pulmonary sarcoidosis: “sarcoid galaxy” sign. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002 Jun;178(6):1389–93.

16. Abehsera M, Valeyre D, Grenier P, Jaillet H, Battesti JP, Brauner MW. Sarcoidosis with pulmonary fibrosis: CT patterns and correlation with pulmonary function. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000 Jun;174(6): 1751–7.

17. Sayball K, Iden T, Syed A, Farner L, Groves R, James W. Presence of Ground Glass Opacities on Chest Imaging Varies by Race and Correlates With Decreased Lung Function in Patients With Sarcoidosis. CHEST. 2015 Oct 1;148(4):398A

18. Mostard RLM, van Kroonenburgh MJPG, Drent M. The role of the PET scan in the management of sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2013 Sep;19(5): 538–44.

19. Bourbonnais JM, Samavati L. Clinical predictors of pulmonary hypertension in sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2008 Aug;32(2):296–302.

20. Devaraj A, Wells AU, Meister MG, Corte TJ, Wort SJ, Hansell DM. Detection of pulmonary hypertension with multidetector CT and echocardiography alone and in combination. Radiology. 2010 Feb;254(2):609–16

21. Goyal A, Gupta D, Agarwal R, Bal A, Nijhawan R, Aggarwal AN. Value of different bronchoscopic sampling techniques in diagnosis of sarcoidosis: a prospective study of 151 patients. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2014 Jul;21(3):220–6

22. Wang KP, Fuenning C, Johns CJ, Terry PB. Flexible transbronchial needle aspiration for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1989 Apr;98(4 Pt 1):298–300

23. Calaras D, Munteanu O, Scaletchi V, Simionica I, Botnaru V. Ventilatory disturbances in patients with intrathoracic sarcoidosis – a study from a functional and histological perspective. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2017;34(1):58–67.

24. Harrison BD, Shaylor JM, Stokes TC, Wilkes AR. Airflow limitation in sarcoidosis—a study of pulmonary function in 107 patients with newly diagnosed disease. Respir Med. 1991 Jan;85(1):59 –64