Affordable Chest Tube Training Simulator for EM Residents

Making Chest Tube Thoracostomy Training Realistic, Efficient, and Affordable

Andrew Eyre1, John Eicken2, David Meguerdichian1, Eric Nadel3, Roger Dias4, Valerie Dobiesz1

- Brigham and Women’s Hospital/ Harvard Medical School

- Prisma Health-Upstate/University of South Carolina School of Medicine

- Brigham and Women’s Hospital/ Massachusetts General Hospital/ Harvard Medical School

- STRATUS Center for Medical Simulation/Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Email: [email protected]

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 28 February 2025

CITATION: Eyre, A., Eicken, J., et al., 2025. Making Chest Tube Thoracostomy Training Realistic, Efficient, and Affordable. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(2). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i2.6350

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i2.6350

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Background: Procedural competency is a vital component of emergency medicine (EM) residency. Chest tube thoracostomy can be an emergent lifesaving procedure that all graduating EM residents should be competent in performing. Simulated task trainers for tube thoracostomy are commercially available and described in the literature, however, financial constraints and anatomical inconsistencies represent drawbacks of these devices.

Methods: TITUS (Thoracic Intervention Training Unit Simulator) was developed to create a chest tube thoracostomy model that is easy to assemble, realistic, portable and affordable. TITUS is comprised of a plastic mannequin torso and basic hardware supplies and can be assembled for under $50. Using TITUS, we performed a cross-sectional survey-based study as part of procedure education session.

Results: A total of 29 EM residents completed the survey. Most participants had little prior experience placing open chest tubes or pigtail catheters. Using the TITUS model, participant comfort levels rose from 2.6 + 0.98 (where 1= not at all comfortable and 5= extremely comfortable) before the educational session to 3.7 + 0.85 (p < 0.001, z = -0.49). Participants rated TITUS to be more realistic than other chest tube simulators (n=28, average= 4.2 where 1=much less realistic and 5=much more realistic) and rated it to be highly realistic compared to cadavers or live patients (n=22, average=3.8 where 1=much less realistic and 5=much more realistic). Participants reported that the educational session improved their ability to place chest tubes (average=4.2, where 1=decreased and 5=greatly improved).

Conclusions: Our results indicate that TITUS provides a realistic, affordable, and easy-to-assemble alternative to currently available thoracostomy simulators.

Keywords

chest tube thoracostomy, simulation, emergency medicine, training, procedural competency

Introduction

Procedural competency is a vital component of emergency medicine (EM) training and part of the EM Milestone matrix that should be acquired during residency. Chest tube insertion (tube thoracostomy) is an emergent, lifesaving procedure that all EM residents should master prior to graduation. Practicing high-acuity, low-frequency procedures through the use of simulation affords trainees the opportunity to learn and practice crucial skills prior to performing invasive procedures on a live patient. Currently, commercially-available and self-made models exist, however, each has significant limitations. Ideally, chest tube training models should be realistic, inexpensive, easily constructed, reproducible, portable, anatomically accurate, and easy to reset between learners. Traditionally, tube thoracostomy is taught through the review of anatomical landmarks and supervised bedside teaching on real patients. Such an approach has become increasingly limited in training programs due to resident duty hours, public demand for safer practices that decrease patient risk, and economic pressures driving hospitals to more efficient care processes that limit resident experiences. Simulation has proven to be an effective modality for teaching chest tube insertion. In a study of 500 physicians-in-training, respondents indicated significant interest in obtaining simulation-based training for invasive procedures prior to practicing these procedures on live patients. Stronger preferences were reported for more complicated procedures. In fact, most respondents preferred that simulation be used to teach chest tube placement. In addition to improving success rates and overall performance, simulation-based chest tube training has been shown to significantly decrease procedure time when compared to non-simulation training. Simulation mannequins, cadaveric models, animal models, serious gaming approaches, and simulation task trainers for tube thoracostomy have all been used and shown to be effective in teaching residents and students. Nonetheless, financial constraints, poor fidelity, and anatomical inconsistencies pose potential barriers to trainees experiencing an optimal simulation experience.

In an effort to address and overcome the limitations of existing chest tube thoracostomy simulators, we designed and tested an innovative chest tube insertion simulator called TITUS (Thoracic Intervention Training Unit Simulator). TITUS was developed to be an inexpensive, easily constructed, portable, and reusable simulator that provides learners with realistic anatomic landmarks and tissue fidelity. Furthermore, this task trainer was designed to facilitate rapid transition and turnover between learners in order to afford adequate skill training and exposure to this high risk, low frequency procedure for large groups of EM and surgical trainees. Specifically, the objectives of this study were to: 1) design and construct a low-cost, portable, and realistic chest tube model 2) demonstrate the ease of designing this model and 3) assess the impact of this chest perceived confidence level with the procedure.

Materials and Methods

STUDY DESIGN, SETTING AND PARTICIPANTS

This was a cross-sectional, survey-based study. Participants were a convenience sample of EM residents from our 4-year EM residency training program and no exclusion criteria were used. As part of the normal didactics program, all residents attending a procedural skills session were invited to participate in this study. Participation in the study was voluntary and based on institutional guidelines, this study was exempt from formal IRB review.

SIMULATOR SPECIFICATIONS

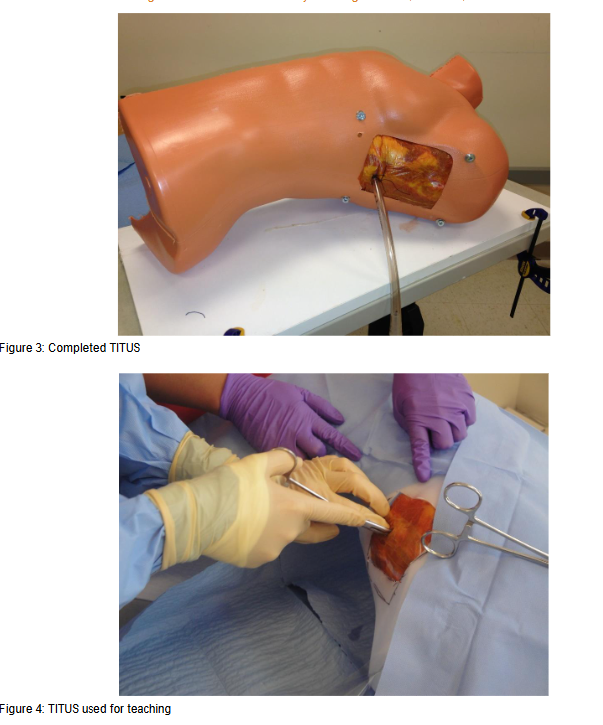

The TITUS is comprised of a plastic mannequin torso and basic hardware supplies that when constructed creates an anatomically correct base and bracket system that facilitates convenient and secure loading of porcine ribs into the unit. The materials for a TITUS simulator cost approximately $50 (US dollars) and a single person can assemble a TITUS in approximately two hours.

To create TITUS, a plastic mannequin torso was purchased from an online retailer and hemisected using a saw, thus providing the chest wall base for two simulators. Following correct anatomical landmarks, a saw was used to cut out a small rectangle in the axilla and lateral aspect of the anterior latissimus dorsi, the lateral pectoralis major, and a horizontal line extending through the nipple and associated intercostal space. Using screws, the plastic torso was attached to a pre-cut wooden shelf to create a stable, portable platform. Segments of PVC pipe and T-Shaped PVC connectors were attached to the inner portion of the torso using polyurethane glue (Gorilla Glue Company, Sharonville, OH), in an anterior to posterior direction, providing additional strength and stability to the model. A total of four small holes were drilled approximately 1cm beyond the corners of the resected chest wall rectangle. Screws were inserted from the external surface through these holes. An internal bracket system was created when these screws were attached to vertically oriented metal mending plates within the torso using washers and wing nuts.

To prepare the model, a rack of porcine ribs, purchased for $12 (US Dollars) at a local grocery store, is cut into short, 4-5 rib segments. Each segment is wrapped in Ioban (3M) or commercially available plastic food wrap in order to minimize fluid leakage and learner exposure during the training session. Each segment of ribs is then covered with foam or any available simulated suture pad which replicates skin and subcutaneous tissue. Together, the ribs and suture pad are inserted from the inside of the torso in an anatomically correct fashion that occludes the resected rectangle. The bracket system is then tightened to secure the ribs and foam in place. When completed, TITUS simulates a patient lying in the supine position with actual tissue that can be palpated and instrumented in an anatomically realistic location. Each rib segment can be used multiple times before being rapidly and easily replaced as necessary depending on the number of learners during teaching sessions.

MEASUREMENT AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

To evaluate the effect that the model had on participant education, emergency medicine residents were asked to complete a brief survey after using TITUS as part of a procedure training didactic session. The anonymous, brief survey consisted of a mix of multiple choice and Likert-type questions (Appendix A). Continuous data were reported as mean, median and standard deviation. Categorical data was reported as absolute number (N) and percentage (%). For comparison of the comfort level (ordinal variable) before and after the training session, the Wilcoxon Signed Ranks test was used and a p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical software SPSS (version 22.0) was used.

Results

From a cohort of 60 EM residents in the training program, 30 participated in the procedure skills sessions and all participants agreed to participate in this study. A single resident did not complete the entire survey and was excluded from the analysis, resulting in 29 EM residents (8 PGY1, 7 PGY2, 10 PGY 3, 4 PGY4). Most participants had little or no experience placing open chest tubes in actual patients (8 (28%) with 0 live chest tubes, 13 (45%) with 1-5 live chest tubes, 7 (24%) with 6-10 live chest tubes, and 1 (3%) with 15 or more live chest tubes. Similarly, most participants were inexperienced in placing percutaneous (pigtail) chest tubes (9 (31%) with 0 live pigtails, 19 (66%) with 1-5 live pigtails, and 1 (3%) with 6-10 pigtails).

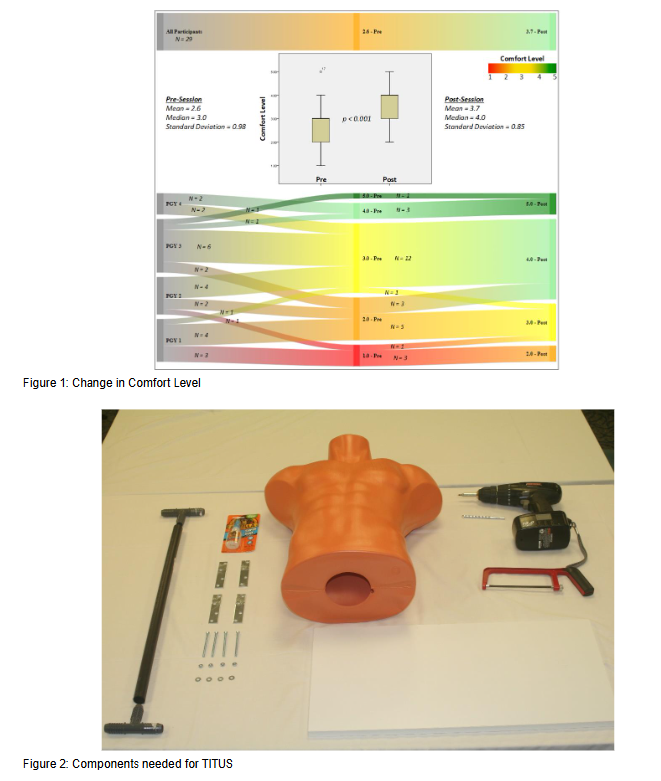

Using the TITUS model, participant comfort levels rose from 2.6 + 0.98 (where 1= not at all comfortable and 5= extremely comfortable) before the educational session to 3.7 + 0.85 after the educational session (p < 0.001, z = -0.49).

displays these findings stratified for each group of residents (postgraduate year 1 to 4).

Of the respondents with prior experience using other chest tube simulators, participants rated TITUS to be more realistic (n=28, average= 4.2 where 1=much less realistic and 5=much more realistic). Similarly, of respondents with prior experience placing a chest tube in a live human or cadaver, participants reported that TITUS was highly realistic (n=22, average=3.8 where 1=much less realistic and 5=much more realistic). Overall, participants reported that the educational session improved their ability to place chest tubes (average=4.2, where 1=decreased and 5=greatly improved).

Discussion

Mastering the technical skills and ability to practice the high acuity, low frequency procedure of tube thoracostomy is an important part of EM training. With the development of the TITUS model, we have addressed a need in the realm of procedural education for an affordable, realistic, versatile, and effective simulator for teaching and practicing both open chest tube thoracotomy and pigtail catheter placement. Following the design of this novel simulator, our survey study of EM trainees confirmed these assertions. After using TITUS in an educational session, not only did our participants report a significant increase in their own comfort level performing these procedures, but they also reported the model to be more authentic and realistic than other simulators they had used. TITUS was shown to be an effective method of teaching a procedural skill to our residents, many of whom had never or very infrequently performed this procedure on live patients. Although our data was collected from EM residents, TITUS has subsequently been used successfully in training sessions for both EM and general surgery providers.

Chest tube thoracotomy and pigtail catheter placement remain vital skills for EM providers. However, as minimally invasive techniques become more common and there is increased scrutiny on patient safety, these procedures are becoming less frequent and thus more challenging to learn and practice. Simulation minimizes patient risks while providing opportunities for safe and consistent repetition, thus making it an ideal modality for teaching high acuity and increasingly low-frequency procedures. There are commercially available and fabricated chest tube simulators described in the literature. These simulators, however, have limitations in cost, feasibility, and fidelity. Most commercially available chest tube simulators are expensive and require frequent replacement of costly components which limits their availability to a large number of learners and trainees, particularly those practicing in low-resource environments. Other simulators are heavy, bulky, and difficult to set-up and transport. Many simulators use synthetic components that do not effectively or realistically provide users with the tactile feel of working with actual tissue. Similarly, many non-commercial chest tube simulators lack fidelity with regards to the anatomical landmarks and patient positioning that are important to safely performing this procedure. The unique design of TITUS combines the realistic feel of actual animal tissue with an anatomically accurate base, thus allowing learners the opportunity to learn and practice the essential steps of this procedure in a low stress manner that aligns with the promotion of patient safety.

The TITUS model was designed and successfully addresses many of the limitations associated with other available simulators providing a realistic, affordable, and versatile training model. Our results demonstrate that TITUS improved our comfort level in chest tube placement and was a realistic model. Future studies using validating assessment tools and correlation to clinical performance will be an important next step.

Limitations

A key limitation for our design and study is that TITUS cannot fully replace the cognitive and technical experiences of placing a chest tube in an actual, live patient but it can simulate this procedure in a setting that is safe and protects both learners and patients. This simulator does not actively bleed thus learners do not have the opportunity to manage a large volume of blood from the tube, a bloody field, or the actual drainage system in a realistic fashion. Our model also does not simulate pain to provide users with the opportunity to manage pain. Future models of TITUS can potentially integrate bleeding to more closely simulate a live human. Despite these fidelity limitations, TITUS provides a realistic option to master this procedure in a setting that is safe and protected for learners.

A second limitation is that this was a small pilot study in a single center and thus the results may not be generalizable. Surveys were taken of a small cohort of EM trainees from a single EM residency program. Furthermore, our study did not directly perform structured assessments or measure performance, and, therefore, our findings cannot be used to assess the effect of TITUS on learners’ procedural competency. Finally, while we asked participants to compare TITUS to their experiences with other types of training models, we did not directly compare our model to cadaveric models, animal models, or other available simulators.

Conclusion

Chest tube insertion remains an essential yet increasingly infrequent procedure in emergency medicine. Simulation, therefore, serves as an ideal modality for teaching and practicing this vital skill. While many commercial and custom-made chest tube simulators exist, many are prohibitively expensive while others lack necessary fidelity and anatomic realism. Similarly, cadaveric models are expensive and often difficult for training programs to access. TITUS was designed to address these challenges by creating a model that is inexpensive and easily constructed while retaining tissue and anatomic fidelity. Our results indicate that TITUS was viewed by users as realistic and, more importantly, participants reported that their confidence and ability to place chest tubes significantly increased following an educational session using TITUS. The TITUS model provides physicians with a practical solution for the training, practice, and maintenance of tube thoracostomy skills. Further investigation regarding the impact that TITUS has on procedural competency is needed.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no relevant conflicts to report.

Funding Statement

None.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author Contributions

Concept and Design (AE, JE, DM, EN) Acquisition of Data (AE, JE, DM) Analysis and Interpretation (AE, JE, DM, RD, VD) Drafting of Manuscript (AE, JE, DM, RD, VD) Critical Revision (AE, JE, DM, RD, VD) Statistical Expertise (RD)

References

- Emergency Medicine Milestones. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/EmergencyMedicineMilestones.pdf. Accessed January 8, 2019.

- Tatli O, Turkmen S, Imamoglu M, et al. A novel method for improving chest tube insertion skills among medical interns. Using biomaterial-covered mannequin. Saudi Med J. 2017;38(10):1007-1012. doi:10.15537/smj.2017.10.21021

- Netto FACS, Sommer CG, Constantino M de M, Cardoso M, Cipriani RFF, Pereira RA. Teaching project: a low-cost swine model for chest tube insertion training. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2016;43(1):60-63. doi:10.1590/0100-69912016001012

- Gupta AO, Ramasethu J. An innovative nonanimal simulation trainer for chest tube insertion in neonates. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3):e798-805. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-0753

- Al-Qadhi SA, Pirie JR, Constas N, Corrin MSC, Ali M. An innovative pediatric chest tube insertion task trainer simulation: a technical report and pilot study. Simul Healthc. 2014;9(5):319-324. doi:10.1097/SIH.0000000000000033

- Ching JA, Wachtel TL. A simple device to teach tube thoracostomy. J Trauma. 2011;70(6):1564-1567. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e318213f5bc

- Sinclair C. Model for teaching insertion of chest tubes. J Fam Pract. 1984;18(2):305-308.

- Shefrin AE, Khazei A, Hung GR, Odendal LT, Cheng A. The TACTIC: development and validation of the Tool for Assessing Chest Tube Insertion Competency. CJEM. 2015;17(2):140-147. doi:10.2310/8000.2014.141406

- Ghazali A, Breque C, Leger A, Scepi M, Oriot D. Testing of a Complete Training Model for Chest Tube Insertion in Traumatic Pneumothorax. Simul Healthc. 2015;10(4):239-244. doi:10.1097/SIH.0000000000000071

- Greene AK, Zurakowski D, Puder M, Thompson K. Determining the need for simulated training of invasive procedures. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2006;11(1):41-49. doi:10.1007/s10459-004-2320-y

- Chung TN, Kim SW, You JS, Chung HS. Tube thoracostomy training with a medical simulator is associated with faster, more successful performance of the procedure. Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2016;3(1):16-19. doi:10.15441/ceem.15.097

- Leger A, Ghazali A, Petitpas F, Guechi Y, Boureau-Voultoury A, Oriot D. Impact of simulation-based training in surgical chest tube insertion on a model of traumatic pneumothorax. Adv Simul (London, England). 2016;1:21. doi:10.1186/s41077-016-0021-2

- Hutton IA, Kenealy H, Wong C. Using simulation models to teach junior doctors how to insert chest tubes: a brief and effective teaching module. Intern Med J. 2008;38(12):887-891. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.2007.01586.x

- Carter YM, Wilson BM, Hall E, Marshall MB. Multipurpose simulator for technical skill development in thoracic surgery. J Surg Res. 2010;163(2):186-191. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2010.04.051

- Tan TX, Buchanan P, Quattromani E. Teaching Residents Chest Tubes: Simulation Task Trainer or Cadaver Model? Emerg Med Int. 2018;2018:9179042. doi:10.1155/2018/9179042

- Haubruck P, Nickel F, Ober J, et al. Evaluation of App-Based Serious Gaming as a Training Method in Teaching Chest Tube Insertion to Medical Students: Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(5):e195. doi:10.2196/jmir.9956

- Ballard HO, Shook LA, Iocono J, Turner MD, Marino S, Bernard PA. Novel animal model for teaching chest tube placement. J Ky Med Assoc. 2009;107(6):219-221.

Appendix A: Chest Tube Survey

CHEST TUBE SIMULATOR (TITUS) SURVEY

- Age:

- Gender:

- Specialty:

- Level of Training (Circle all that apply): MD PA NP RN

- Approximately how many chest tubes/pigtail catheters did you place during residency (Circle one)?

- 0

- 1-10

- 10-20

- 20-30

- More than 30

- Approximately how many chest tubes have you placed since you finished residency (Circle one)?

- 0

- 1-10

- 10-20

- 20-30

- More than 30

- If you have placed a chest tube in a human, how well does the TITUS Model simulate actual chest tube placement (Circle one)?

- 1 2 3 4 5 Not at all realistic Very Realistic

- How did the TITUS Chest Tube Simulator affect your clinical skills (Circle one)?

- 1 2 3 4 5 Decreased Greatly Improved

- How did the TITUS Chest Tube Simulator affect your confidence in placing chest tubes (Circle one)?

- 1 2 3 4 5 Decreased Greatly Improved

- Do you feel like your work-place would benefit from a low-cost, realistic chest tube simulator (Circle one)?

- yes

- no