Albinism in Angola: A Public Health Perspective

Albinism in Angola as a Public Health Issue

Francisco João Pinto1

- Agostinho Neto University. UNINET – Center for Studies, Scientific Research and Advanced Training in Computer Systems and Communication University Campus of the Camama, S/N, Luanda-Angola.

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 April 2025

CITATION: Pinto, FJ., 2025. Albinism in Angola as a Public Health Issue. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(4). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i4.6367

COPYRIGHT: This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i4.6367

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

In this work we describe albinism in Angola as a public health issue. In Angola there is an estimated population of around 34 million people, 6818 are albinos and only around 2000 people are monitored by the national health service. Oculocutaneous albinism (OCA) is a genetically inherited autosomal recessive condition and OCA2, tyrosine positive albinism, is the most prevalent type found across Angola. Due to the lack of melanin, people with albinism are more susceptible to the harmful effects of exposure to ultraviolet radiation. This population must deal with issues such as photophobia, decreased visual acuity, extreme sun sensitivity and skin cancer. People with albinism also face social discrimination as a result of their difference in appearance. The World Health Organization is currently investigating issues relating to this vulnerable population.

Keywords: Albinism, Angola, public health issue

Introduction

Albinism is characterized as a rare and inherited recessive disease, caused by the complete absence or reduction of melanin biosynthesis in melanocytes, associated with a variable hypopigmentation phenotype, which can affect pigmentation only in the eyes (ocular albinism) or in the eyes and skin (oculocutaneous albinism)”. The word albino comes from the Latin term “Albus”, which means white, and is also synonymous with acromo, achromia and achromatosis, which means deficiency or absence of pigmentation in tissues.

The prevalence of albinism varies globally, with a worldwide incidence of 1 in every 20,000 inhabitants, which Sub-Saharan Africa being the region where the highest incidence is recorded, with 1 in every 5,000 people, in addition to communities that have high consanguinity, notably the Bhatti tribe in Pakistan and the Kuna people in Panama, with prevalences of 5 in every 100 people and between 5 and 10 in every 100 people, respectively. Angola, in turn, has few epidemiological mapping studies on albinism, however, it is assumed that around 6,818 Angolans are albinos, according to data from the Primary Health Care Secretariat of the Ministry of Health. Due to the decrease or absence of melanin, responsible for being a barrier against ultraviolet rays, albino individuals are more susceptible to actinic damage, ranging from sunburn to malignant basal cell lesions.

This condition, especially in a tropical country like Angola, with a high incidence of solar radiation throughout the year, is a major social determinant of health, as it causes, in addition to the aforementioned nosological damage, socioeconomic vulnerabilities, as these individuals have work limitations, such as vision problems or contraindications to prolonged exposure to sunlight. Furthermore, people with albinism are targets of discrimination and invisibility. The lack of accessibility, educational barriers, social stigma are factors that generate a cycle of poverty and oppression against this population.

Therefore, this study, when considering albinism as a public health problem, aims to provide a brief historical perspective of albinism, deconstruct the main mysticisms, prejudices and subjectivities, in addition to giving visibility to the albino population in the fight for their rights. Albinism is a genetic condition that affects melanin, a substance that pigments the skin, hair and other tissues. This condition of absence or significant reduction of melanin has intrigued humanity throughout history. In this work we will explore albinism in Angola as a public health issue.

Theoretical foundation

Genetics is the study of genes and tries to explain what they are and how they work. Genes are living organisms inherit characteristics or traits from their ancestors; for example, children usually look like their parents because they have inherited their parents’ genes. Genetics tries to identify which characteristics are inherited and to explain how these characteristics are passed from generation to generation.

Some characteristics are part of an organism’s physical appearance, such as eye color or height. Other types of characteristics are not easily seen and include blood types. Some characteristics are inherited through genes, which is the reason why tall and thin people tend to have tall and thin children. Other characteristics come from interactions between genes and the environment. The way our genes and environment interact to produce a trait can be complicated. For example, the probability of somebody dying of cancer or heart disease seems to depend on both their genes and their lifestyle.

Genes are made from a long molecule called DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), which is copied and inherited across generations. DNA is a molecule that contains the genetic information for an organism´s development and function. It is passed from one generation to the next. A mutation is a sequential change in DNA, which can occur naturally or be caused by external factors. This appearance of new characteristics is important in revolutionizing organism.

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, or extra chromosomal DNA. It creates slightly different versions of the same genes, called alleles. These small differences DNA sequence make every individual unique.

2.1 GENES AND INHERITANCE

All organisms inherit the genetic information specifying their structure and function form their parents. Likewise, all cells arise from preexisting cells, so the genetic material must be replicated and passed from parent to progeny cell at each cell division.

Genes are pieces of DNA that contain information for the synthesis of ribonucleic acids (RNAs) or polypeptides. They are inherited as units, with two parents dividing out copies of their genes to their offspring. Humans have two copies of each of their genes, but each egg or sperm cell only gets one of those copies for each gene. An egg and sperm join to form a zygote with a complete set of genes. The resulting offspring has the same number of genes as their parents, but for any gene, one of their two copies comes from their father and one from their mother.

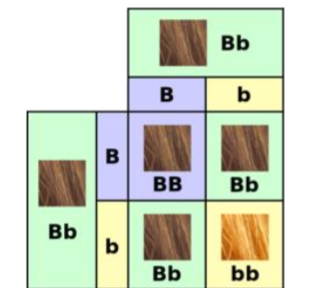

Example of crossing: The effects of crossing depend on the types (the alleles) of the gene. If the father has two copies of an allele for red hair, and the mother has two copies for brown hair, all their children get the two alleles that give different instructions, one for red hair and one for brown. The hair color of these children depends on how these alleles work together. If one allele dominates the instructions from another, it is called the dominant allele, and the allele that is overridden is called the recessive allele. In the case of a daughter with alleles for both red and brown hair, brown is dominant and she ends up with brown hair.

Now imagine that this woman and has children with a brown-haired man who also has a brown-haired genotype. Her ova will be a crossing of two types, one type containing the B allele, and one type the b allele. Similarly, her partner will produce a crossing of two types of sperm containing one or the other of these two alleles. When the transmitted genes are joined up in their offspring, these children have a chance of getting either brown or red hair, since they could get a genotype of BB = brown hair, Bb = brown hair or bb = red hair. In this generation, there is, therefore, a chance of the recessive allele showing itself in the phenotype of the children. Some of them may have red hair like their grandfather.

Red hair is a recessive characteristic. Although the red color allele is still there in this brown-haired girl, it doesn’t show. This is a difference between what is seen on the surface (the traits of an organism, called its phenotype) and the genes within the organism (its genotype). In this example, the allele for brown can be called “B” and the allele for red “b” (It is normal to write dominant alleles with capital letters and recessive ones with lower-case letters). The brown hair daughter has the “brown hair phenotype” but her genotype is Bb, with one copy of the B allele, and one of the b alleles.

Now imagine that this woman and has children with a brown-haired man who also has a Bb genotype. Her ova will be a crossing of two types, one type containing the B allele, and one type the b allele. Similarly, her partner will produce a crossing of two types of sperm containing one or the other of these two alleles. When the transmitted genes are joined up in their offspring, these children have a chance of getting either brown or red hair, since they could get a genotype of BB = brown hair, Bb = brown hair or bb = red hair. In this generation, there is, therefore, a chance of the recessive allele showing itself in the phenotype of the children. Some of them may have red hair like their grandfather.

2.2 HOW GENES WORK

It consists of two major steps: transcription and translation. Together, transcription and translation are known as gene expression. During the process of transcription, the information stored in a gene’s DNA is passed to a similar molecule called RNA (ribonucleic acid) in the cell nucleus.

The basic unit of heredity passed from parent to child. Genes are made up of sequences of DNA and are arranged, one after another, at specific locations on chromosomes in the nucleus of cells. The functional and physical unit of heredity passed from parent to offspring. Genes are pieces of DNA, and most genes contain the information for making a specific protein.

Our genes carry information that gets passed from one generation to the next. For example, genes are why one child has blonde hair like their mother, while their sibling has brown hair like their father. Genes also determine why some illnesses run in families and whether babies will be male or female.

While the human genome contains an estimated 20,000 protein-coding genes, the coding segments of those genes—the exons—comprise less than 2% of the genome; most of the genome consists of DNA that lies between genes, far from genes or in vast areas spanning several million base pairs (Mb) that appear to contain no genes.

The gene occurs in the same position on each chromosome. Genetic traits, such as eye color, are dominant or recessive: Dominant traits are controlled by 1 gene in the pair of chromosomes. Recessive characteristics need both genes in the gene pair to work together.

Generators don’t actually create electricity. Instead, they convert mechanical or chemical energy into electrical energy. They do this by capturing the power of motion and turning it into electrical energy by forcing electrons from the external source through an electrical circuit.

The human reference genome contains somewhere between 19,000 and 20,000 protein-coding genes. These genes contain an average of 10 introns and the average size of an intron is about 6 kb (6,000 bp).

Genes are at the center of everything that makes us human. They are responsible for producing the proteins that run everything in our bodies. Some proteins are visible, such as the ones that compose our hair and skin. Others work out of sight, coordinating our basic biological functions. While the human genome contains an estimated 20,000 protein-coding genes, the coding segments of those genes—the exons—comprise less than 2% of the genome; most of the genome consists of DNA that lies between genes, far from genes or in vast areas spanning several million base pairs (Mb) that appear to contain no genes.

2.3 Genetic disorder

A genetic disorder is a health problem caused by abnormalities in the genome. They are heritable, and may be passed down from the parents’ genes to their children and to later generations. If a genetic disorder is present from birth, it is described as a congenital defect. Some defects only show up in later life.

The mutation responsible can occur spontaneously before the embryo develops, or it can be inherited from parents who are carriers of a faulty gene. There are well over 6,000 known genetic disorders, and new genetic disorders are constantly being found. More than 600 genetic disorders are treatable. Around 1 in 50 people are affected by a known single-gene disorder, while around 1 in 263 are affected by a disorder caused by their chromosomes. Parts of a chromosome may be absent, or duplicated.

About 65% of people have some kind of health problem as a result of congenital genetic mutations. About 1 in 21 people are affected by a genetic disorder classified as “rare” (less than 1 in 2,000 people). Most genetic disorders are rare in themselves. They may affect one person in every several thousands or even millions. Sometimes they are relatively frequent in a population. If they are frequent, it suggests these recessive gene disorders give an advantage in certain environments when only one copy of the gene is present. Sickle cell anemia is an example of this.

The same disease, such as some forms of cancer, may be caused by an inherited genetic condition in some people, by new mutations in other people, and by non genetic causes in still other people. A disease is only called a genetic disease if it can be inherited at birth. The particular defect may only show up later in life.

Methodology

In this work, we used quantitative observation as a research method, which allowed us to collect numerical data about the phenomenon. It also allowed us to quantify the problem and understand its dimension, as well as to investigate and observe the phenomenon comprehensively.

This is a qualitative observational study, which used Google Scholar and Virtual Health Library databases. The search strategy used the descriptors “Albinism”, “Angola” and “Public health issue”. 375 results were found, but after reading the titles, 10 articles were selected, according to the inclusion criteria of addressing the topic of albinism, which were read in their entirety. Furthermore, official documents from the Angolan Ministry of Health were analyzed, based on the Virtual Health Library database, and from the High Commissioner for Human Rights of the United Nations, in its annual report on albino people in the world.

3.1 A BRIEF PHENOTYPIC DESCRIPTION OF HUMAN ALBINISM: OCULAR, OCULOCUTANEOUS AND SYNDROMIC FORMS

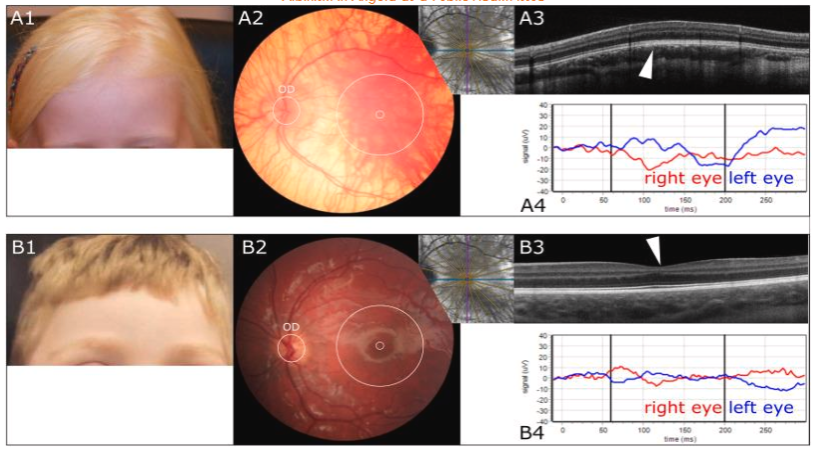

In humans, albinism affects melanosomal pigmentation in the eye, skin and hair. In addition, patients have the following ocular abnormalities: nystagmus, iris translucency, fundus hypopigmentation, foveal hypoplasia and chiasmal misrouting. These abnormalities result in reduced visual acuity (VA) in patients. As melanin prevents excessive DNA-damage by UV radiation, a large subset of persons with albinism can be prone to skin cancer, unless adequate protective measures (sunscreen, clothing) are implemented.

The clinical diagnosis of albinism is based on examination of the eyes, skin, hair, and assessment of chiasmal misrouting. The diagnosis can be confirmed by pedigree analysis and DNA diagnostics of all known albinism disease genes. Of note, in approximately 25–30% of patients no disease-causing mutations have been identified (yet). Ocular examination includes best corrected VA measurement, slit lamp examination to assess iris translucency, and fundoscopy to assess pigmentation levels. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) scans are used to determine the degree of foveal hypoplasia, measured using the Leicester grading system (Thomas et al., 2011). OCT is also used to record the asymmetry of the ganglion cell layer thickness between the nasal and temporal areas of the retina, as found in patients with albinism. Analysis of visual evoked potentials (VEPs) is used to assess optic nerve misrouting.

In oculocutaneous albinism (OCA), the pigmented skin, eyes, and hair are all affected to a variable degree. In OA1, the hypopigmentation is mostly restricted to the eyes (iris and retina). Nonetheless, some evidence suggests that OA1 may also be associated with mild hypopigmentation of the skin. In addition to OCA and OA1, Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome (HPS) and Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS) include albinism in their pathological spectrum. Albinism deafness syndrome(s), including the autosomal dominant Tietz syndrome, as well as Waardenburg syndrome type 2, caused by mutations in MITF, are clinically considered auditory-hypopigmentation syndromes and are excluded from this report. MITF is only briefly mentioned as it is a transcription factor that affects expression of a number of melanosomal genes. Griscelli syndrome can also be considered a syndromic form of human albinism, but it has no consistent ocular phenotype and is therefore excluded from this report. Finally, FHONDA (foveal hypoplasia, optic nerve decussation defects and anterior segment dysgenesis) is an autosomal recessive syndrome with remarkable similarities to albinism, including nystagmus, foveal hypoplasia and misrouting of the optic nerve fibres. However, an abnormal pigmentary phenotype is absent.

3.2 ALBINISM IN ANGOLA AS A PUBLIC HEALTH ISSUE

Angola is located in Southern Africa, on the Atlantic coast, between Namibia and the Republic of Congo. It has an area of 1,246,700 km2, an Atlantic coastline of 1,650 km and is bordered by the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Zambia to the east. The country has a tropical climate and plateau relief.

In Angola there are around 34 million of people and it is estimated that there are 6,818 people with albinism, with over 2,000 people with albinism being monitored by the National Health System. Albinism is protected by the principle of equality, enshrined in article 77º of the Constitution of the Republic. Presidential Decree number 193/23 of October 9 establishes social protection measures for people with albinism, such as:

- Ensure access to specialized consultations, such as dermatology, ophthalmology, psychology, oncology and sociology

- Ensure access to glasses and sunscreen

- Implement mobile clinics to serve populations in areas without reference hospitals

- Empower people with albinism and their families to promote sun protection behaviors.

The Plan of Action on Albinism in Africa is another social protection instrument for people with albinism. This plan defines areas of strategic intervention, such as:

- Universal access to medical and medication assistance

- Civic education, awareness and literacy

- Social action

- Inclusive and quality school education

- Access to higher education

- Sport as a tool for social integration

- Protective policies and laws to combat stigma and discrimination

Albinism is more common in eastern and southern Africa, and Angola is a country located more or less in southern Africa. In Tanzania, for example, one in every 1,400 people is albino. However, albinism can affect people of all ethnicities. According to the (WHO), it is estimated that one in every five thousand people on the globe has some form of albinism. In Angola, by 2027, at least 7,668 could be included in these statistics. Albinism is a genetic condition characterized by a lack of melanin, the pigment that gives color to the skin, eyes and hair. People with albinism are more vulnerable to sun exposure and can suffer from stigma, discrimination and violence.

3.3 IMPACT ON THE HEALTH OF PEOPLE WITH ALBINISM IN ANGOLA

Albinism is a genetic condition that can have impacts on people’s health, such as:

- Skin cancer; People with albinism are more susceptible to developing skin cancer as they do not have enough melanin to protect their skin from ultraviolet rays.

- Low vision. The most common type of albinism, OCA, can cause problems with low vision.

Sun exposure can cause chemical damage to the skin and premature aging. In addition to significantly affecting appearance, albinism often results in permanent congenital health problems. For example, visual impairments.

3.4 PREVENTING SUN DAMAGE

People with albinism may:

- Use accessories such as brimmed hats and umbrellas;

- Wear tightly woven fabric clothing;

- Use products with sunscreen SPF ≥ 20, 30 minutes before leaving home and reapply every 2 hours.

3.5 LIFE EXPECTANCY OF AN ALBINO PERSON IN ANGOLA

People with albinism are a thousand times more susceptible to this disease, and life expectancy for this group can reach 33 years, due to skin cancer, a condition that can be easily prevented. This is justified by the fact that Angola is a country with a lot of sun and high temperatures. Cancer is one of the most harmful consequences for the physical health of people with albinism. Skin cancer occurs recurrently when the individual does not have access to preventive measures, such as the use of sunscreen.

Results and Discussion

In Angola there is an estimated population of around 34 million people, 6818 are albinos and only around 2000 people are monitored by the National Health Service. Despite the decrease in prejudices regarding people with albinism, the importance of creating effective public policies in Angola, which protect them both from psychosocial stigmas and in terms of physical health, is clear. Therefore, there is an urgent need to qualify health professionals so that they can understand the albino population from both a medical and biological point of view and from a social point of view.

Furthermore, social programs must be based on guaranteeing autonomy for albino people. It is important to emphasize the importance of tools that include the Angolan albino person in education and the job market, in order to guarantee their safety – such as the distribution of sunscreens, clothing with protection against solar rays, the availability of ophthalmological therapies and early screening for skin neoplasms. Furthermore, the media plays a key role in mitigating discrimination and increasing the visibility of albino people, with educational measures and the promotion of narratives that aim at social inclusion and development. Finally, the country still lacks solid epidemiological studies that show the quantitative panorama of the albino population in the country.

Regarding access to healthcare for this population, the stigma and lack of knowledge among healthcare professionals about albinism is a factor that hinders access to healthcare services. Considering that this population is 1000 times more susceptible to developing skin cancer and other lesions, this reality is, unfortunately, a factor of morbidity and mortality that affects the albino population, with a life expectancy of only 33 years. Simple measures, such as the distribution of sunscreen and general guidelines, would be adequate for prevention.

Among the problems reported by albinos in Angola, the albino association highlights the lack of accessibility in some state institutions. Albinos cannot find employment and sometimes are not treated in hospitals because of their condition. These are barriers to employment and also to hospital care.

In Angola, people with albinism can access medical consultations and social support through the Support and Protection Plan for People with Albinism. There is support for priority sectors of support and protection for people with albinism, taking into account Universal Access to Medical Care.

Conclusions

We can conclude that Angola, a country with a population of around 34 million people, has about 6818 people with albinism. But only around 2,000 are monitored by the health service. Therefore, it is a public health issue. Albinism, especially in Angola due to extreme sun exposure, is a condition that requires more attention. Although prevalence data are scarce and further epidemiologic research is needed, the number of people living with albinism in Angola is likely to be as high as tens of thousands. Our findings underscore the need to better address the already known medical problems facing people with albinism, but also issues of social discrimination against this population. Some progress has been made in terms of medical and social care but we hope to further increase the awareness of albinism throughout Angolan society in the future. Public health action should focus on educational, medical and occupational settings.

References

- Angola (2022). Ministério da saúde. Secretária de Atenção Primária á Saúde. Orientação e sensibilização de gestores e profissionais de Atenção Primária á Saúde. Perfil de saúde das Pessoas com Albinismo em Angola e no Mundo.

- Araújo, S. (2021). The beautiful (in) visible of the Albina Child in Children´s literature. Ufpb.br.João Pessoa. Disponível em: https://periodicos.ufpbr.br/ojs2/index.php/caos/article/view/34701. Acesso em 6 / Nov/2024.

- Ero (2021). Pessoas com Albinismo no mundo. Uma Perspectiva de direitos humanos. Disponível em https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Albino m-worldwide-Report2021-PT.pdf. Acessado em: 25/Nov/2024.

- Marçon, C.; Maia, M. (2019). Epidemia genética, caracterização cutânea a factores psicosociais. Departamento de Medicina, Santa casa de Misercódia de São Paulo. Disponível em https://clínica.elsevier.es/, Acesso em 12/Jan/2025.

- Gould, G.M(1893). Journal of the Amercan Medical Association.

- D Creel, C. J., WITKOP, R.A., King. (1974)- Asymmetric visually evoked potentials in human albinos: evidence for visual system anomalies. Investigative Ophthalmology & visual science.

- Jump up to: a b University of Utah Genetics Learning Center animated tour of the basics of genetics. Howstuffworks.com. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- Jump up to: a b Melanocortin 1 Receptor, Accessed 27 November 2024.

- Simons, A. (2024). Chromosomes, Genes, and Traits: An Introduction to Genetics.

- Halder, R.M., Bridgeman-Shah, M.D. (1995) Skin cancer in African Americans – Wiley Online Library. Department of Dermatology, Howard University College of Medicine.

- Kruijt, C. C., Montoliu, L. (2022). The retinal pigmentation pathway in human albinism. National Institute Health, published in Progress in Retinal and Eye Research.

- Brücher, C.V, Peter Heiduschka, P., Ulrike Grenzebach, U., Eter, N., Biermann, J. (2019). Distribution of macular ganglion cell layer thickness in foveal hypoplasia: A new diagnostic criterion for ocular albinism. Published: November 18, 2019 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224410.

- Hoffmann, M.B. (2005). Visual Processing Lab – Dpt Ophthalmology -Otto-von-Guericke-University Magdeburg.

- Schiaffino, M.V., Tacchetti, C. (2005). The ocular albinism type 1 (OA1) protein and the evidence for an intracellular signal transduction system involved in melanosome biogenesis, DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2005.00240.x.

- Keren, G., Lewis, C. (Eds.). (1993). A handbook for data analysis in the behavioral sciences: Methodological issues. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Marjan Huizing, M., May, C. V., Malicdan, Jennifer ´A., Wang, H.P, Richard, A., Hess, R. F., Kevin, J.. O’Brien, M. A. Merideth, W. A. Gahl, B. R. G,(2020). Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome: Mutation update, First published: 03 January 2020 https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.23968.

- Chiang, G. (2009) Effects of Feeding Solid-State Fermented Rapeseed Meal on Performance, Nutrient Digestibility, Intestinal Ecology and Intestinal Morphology of Broiler Chickens. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences, 23, 263-271. https://doi.org/10.5713/ajas.2010.90145.

- Mancini, P.M, Camilleri-Bröet, S. Anderson, B.O., Hockenbery, D. M. (1998). Proliferative mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1566-3124(01)05005-2.

- Constituição da Republica de Angola (CRA), Órgão Oficial, I Série, Nº 154. 16 de Agosto de 2023, Artigo 77º (Saúde e Protecção Social).

- Lim, H.W., Kohli, I., Ruvolo, E.(2022). Impact of visible light on skin health: The role of antioxidants and free radical quenchers in skin protection. J Am Acad Dermatol 86(3S):S27-S37, 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.12.024.

- Lvovs, D.; Favorova, O.O.; Favorov, A.V. (2012). “A Polygenic Approach to the Study of Polygenic Diseases”. Acta Naturae. 4(3):59–71. doi:10.32607/20758251-2012-4-3-59-71. ISSN 2075-8251. PMC 3491892. PMID 23150804.

- “Spontaneous Mutations | Harvard Medical School”. hms.harvard.edu. 2013-05-15. Retrieved 2025-01-08.

- “OMIM Gene Map Statistics”. www.omim.org. Retrieved 2020-01-14.

- “Orphanet: About rare diseases”. www.orpha.net. Retrieved 2020-01-14.

- Bick, David; Bick, Sarah L.; Dimmock, David P.; Fowler, Tom A.; Caulfield, Mark J.; Scott, Richard H. (2021). “An online compendium of treatable genetic disorders”. American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part C, Seminars in Medical Genetics. 187 (1): 48–54. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31874. ISSN 1552-4876. PMC 7986124. PMID 33350578.

- Kumar, Pankaj; Radhakrishnan, Jolly; Chowdhary, Maksud A.; Giampietro, Philip F. (2001). “Prevalence and Patterns of Presentation of Genetic Disorders in a Pediatric Emergency Department”. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 76 (8):777–783. doi:10.4065/76.8.777. ISSN 0025-6196. PMID 11499815.

- Jackson, Maria; Marks, Leah; May, Gerhard H.W.; Wilson, Joanna B. (2018). “The genetic basis of disease”. Essays in Biochemistry. 62 (5): 643–723. doi:10.1042/EBC20170053. ISSN 0071-1365. PMC 6279436. (calculated from “1 in 17” rare disorders and “80%” of rare disorders being genetic).

- “WGBH Educational Foundation”. Archived from the original on 2008-05-14. Retrieved 2013-03-22.

- Carroll, Sean B. (1974). Introdução À Genética – 11ª Ed. [S.l.]: Guanabara Koogan.

- Robinson, Tara Rodden (2005). Genetics for Dummies (em inglês). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Publishing. p. 9. 364 páginas. ISBN 978-0-7645-9554-7.

- Robinson, Tara Rodden (2005). Genetics for Dummies (em inglês). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Publishing. p. 327. 364 páginas. ISBN 978-0-7645-9554-7.

- Hart, Daniel L.; Jones, Elizabeth W. (1998). Genetics. Principles and Analysis 4ª ed. Sudbury, Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. p. 177-182. ISBN 0-7637-0489-X.

- Alberts, Bruce; Johnson, Alexander; Lewis, Julian; Raff, Martin; Roberts, Keith; Walter, Peter (2010). Biologia Molecular da Célula 5 ed. Porto Alegre: Artmed. pp. 553–556. ISBN 978-85-363-2066-3.

- Karp, Gerald (2008). Cell and Molecular Biology. Concepts and Experiments (em inglês) 5ª ed. New Jersey: John Wiley. pp. 727–776. ISBN 978-0-470-04217-5.

- Dale, Jeremy W.; Park, Simon F (2004). Molecular Genetics of Bacteria (em inglês) 4ª ed. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. p. 37-66. 346 páginas. ISBN 0-470-85084-1.

- Gillespie, John H (1998). Population Genetics. A Concise Guide. Baltimore/London: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 1. 169 páginas. ISBN 0-8018-5755-4.

- Albinos (2013). Associação dos albinos da Republica de Angola. Disponível em https://m.redeangola.info/albinos. Acesso 7/Mar/2025.