Balancing Human and Planetary Health with Plant-Based Diets

Balancing Human and Planetary Health Through Plant-Based Diet

Rattan Lal1

- CREATES East Center for Carbon Management and Sequestration, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 28 January 2025

CITATION: Lal, R. 2023. Balancing Human and Planetary Health Through Plant-Based Diet. Medical Research Archives. https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v11i2.4235

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i2.6235

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

Dietary preferences, with strong effects on human health and environmental sustainability including climate change, is an emerging scientific discipline of nutrition ecology. Whereas poor food choices are a serious health issue in low- and middle-income countries, malnutrition (hidden hunger) is also a growing concern in developed economies. A western diet based on red meat may be unhealthy and unsustainable because of its adverse impacts on soil, water, air, biodiversity, and human health. Traditional animal-based diets (ABDs) may have aggravated public-health crisis, accelerated anthropogenic climate change, increased vulnerability to pandemics, and accentuated social/psychological anxieties. In comparison, plant-based diets (PBDs) have low health risks, reduced emission of greenhouse gases (GHGs), and less consumption of water and other natural resources. Adoption of PBDs may benefit people and spare some land and water for nature. In addition to lower health risks (i.e., some cancers, obesity, cardiovascular diseases), PDBs also have life-enhancing potential. Recent increasing focus on PBDs may also be due to ethical concerns about animal welfare and environmental friendliness. However, there are several barriers and challenges to adoption of PBDs. Strict vegan diet may aggravate malnutrition among children, nursing mothers, and elderly population. Rather than a radical transition, a holistic approach to PBDs may be an appropriate strategy. A holistic strategy would include using animal products judiciously, balancing human and planetary health through PBDs, and sparing land/water for nature. In contrast with ABDs, balanced PBDs can improve human health and have a positive environmental impact.

Keywords

Plant-based diet, human health, planetary health, sustainability, nutrition ecology

Introduction

An unhealthy diet is among major causes of vulnerability to non-communicable diseases (i.e., obesity, diabetes, hyper-tension, some cancers, malnutrition), and growing risks of civil unrest and political instability. The adverse effects of predominantly animal-based diets (ABDs) on planetary processes include anthropogenic global warming, water scarcity, loss of biodiversity, etc. Therefore, a trend of shifting from ABDs to plant-based diets (PBDs) is gaining momentum in the interest of enhancing human wellbeing and restoring nature/planetary processes. Interest in PBDs is also growing because of the challenges of ecological sustainability, human health, animal welfare, and strong inter-connectivity among these issues. Indeed, transitioning to PBDs may be an appropriate strategy to addressing global issues of the 21st century, putting Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations Agenda 2030 on track, and reducing the environmental footprint (EFP) of humanity. Examples outlined in Table 1 show notable reduction in EFP through adoption of PBDs. However, without proper planning, requirements of micronutrients for good human health may not be met by PBDs. Thus, there is a strong need to understanding of barriers to a widespread adoption or shift to PBDs.

Table 1. Examples of reduction in environmental footprint by adoption of plant-based diets

| Approach | Impact | References |

|---|---|---|

| Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) | Moving from omnivorous to vegetarian diet reduced environmental impact | Coelho et al., 2016 |

| Cohort & randomized control trials | Adoption of PBD reduced EFP | Viroli et al., 2023 |

| One-Health | Meat products contributed most to EFP | Paris et al., 2024 |

| Cardiovascular Health | PBD is environmentally sustainable dietary option | Satija and Hu, 2018 |

| Plant-based meat (PBM) | Use of PBM have low EFP | Van Vliet et al., 2020 |

| Diet Quality | Low-meat diets are environmentally friendly | Hagmann et al., 2019 |

The objective of this article is to deliberate merits and challenges to adoption of PBDs as a strategy to improve human health while advancing nature conservancy and sustaining planetary processes. The article addresses barriers or challenges to achieving the transition including cultural, social, economic, and political factors which affect acceptability and affordability of PBDs. The article also considers some innovative options such as use of pulses, algal products, and meditation while transitioning to PBDs.

Types of Human Diet

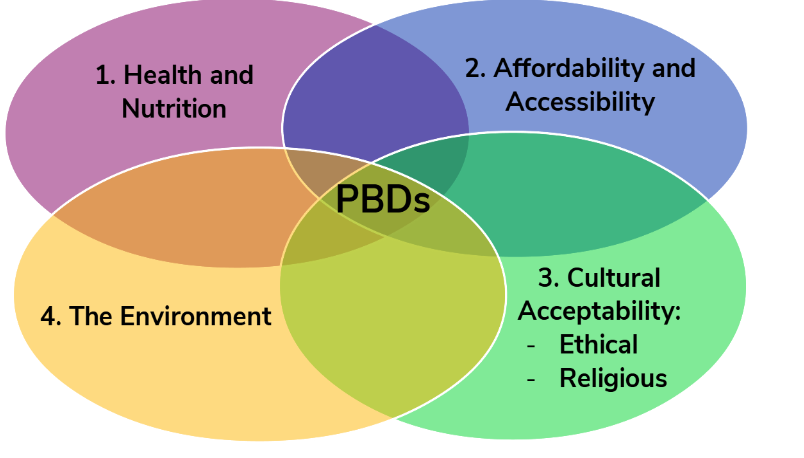

There are four pillars of PBDs (Figure 1), and these must be carefully considered while making choice of specific dietary preferences. Different types of human diet include the following:

THE VEGAN DIET (VGD): It is a vegetarian diet that excludes meat, fish, dairy, honey, and eggs. With proper planning, VGD can have positive effects on obesity, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases (CVDs).

VEGETARIAN DIET (VDD): It is a vegan diet plus use of dairy products (i.e., milk, cheese, yogurt, ghee).

PESCATARIAN DIET (PSD): It includes VGD plus fish and seafood, but no meat or poultry.

FLEXITARIAN DIET (FXD): It is a semi-vegetarian diet that focuses on plant-based food while occasionally including meat. It is a combination of flexible and vegetarian diets.

TERRITORIAL DIVERSIFIED DIET (TDD): It is a flexitarian style diet that includes plant-based food along with seasonal and locally sourced food. Some examples of TDD are Mediterranean and New Nordic Diet.

MEDITERRANEAN DIET (MTD): It involves eating whole unprocessed foods including fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, seeds, and olive oil.

NEW NORDIC DIET (NND): It includes locally sourced sustainable and traditional foods including whole grains, fruits and vegetables, tubers (beets, turnip), fish, and rape seed oil.

TRADITIONAL WESTERN OR AMERICAN STANDARD DIET (TAD): It is high in saturated and trans fats, refined grains, red meat, processed meat, high sugar drinks and high-fat dairy products. TAD is low in plant-based food, and has high calories, excess sugar and sodium content.

Figure 1. Four pillars of PBDs as outlined by Moreno et al. (2022). Without professional supervision, use of PBDs (vegan, vegetarian, and pescetarian) can increase the risks of malnutrition among vulnerable population (e.g., infants, children, women, nursing mothers, and the elderly).

Plant Based Diets With Meditation and Supplements

There is a wide range of PBDs which exclude or reduce intake of animal products. These PBDs have evolved over millennia and are adapted to specific social, cultural, and ecological environments. PBDs are often used in combination with meditation and some supplements to minimize risks of the deficiency of micronutrients and other essential ingredients.

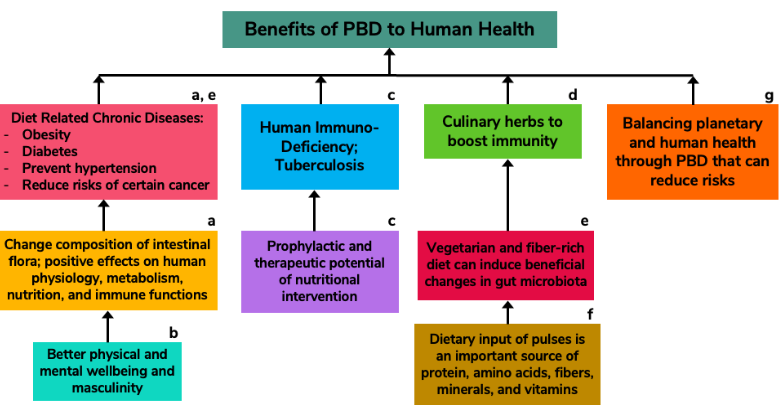

For example, VDD is often combined with meditation for treatment of some psychological, CVDs, and digestive diseases. Potential benefits of PBDs are outlined in Figure 2 and briefly discussed below.

Figure 2. Human-health benefits of plant-based diets: a, b, c, d, e, f, g.

Reduction in Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Adoption of PBDs

One of the ecological benefits of adopting PBDs is the potential of reducing emission of greenhouse gases (GHGs) from predominantly animal-based foods. While more context-specific research may be needed to check the carbon-footprint (CFP) of PBDs, the data from some examples listed in Table 2 are a cause of optimism. Several approaches, including the life cycle assessment (LCA), indicate reduction in CFP by decrease in emission of methane (CH₄) and of nitrous oxide (N₂O) through adoption of PBDs. These GHGs have much higher global warming potential (GWP) compared with that of carbon dioxide (CO₂). Transition to PBDs may also reduce the energy and water footprint (ecological footprint or EFP) and enhance terrestrial biodiversity.

Table 2. Reduction of greenhouse gas emission by adoption of plant-based diet

| Approach | Impact | References |

|---|---|---|

| Individual Carbon Footprint (CFP) | Adoption of PBDs can reduce CFP by 20% and decrease GHG emissions | Rancilio et al., 2022 |

| Anthropogenic GHG Emissions | Reducing meat consumption can decrease GHG emission in Sweden | Martin and Brando, 2017 |

| Dietary Shift | Reducing meat may decrease GHG emissions and reduce loss of biodiversity | Stoll-Kleemann and Schmidt, 2017 |

| Resource Management | Shift to PBD is necessary to mitigating anthropogenic climate change | Mayes, 2017 |

| Food-Energy-Water (FEW) Nexus | Balanced diet habits can save water, energy, and natural resources | Kheirinejad et al., 2024 |

| Life Cycle Assessment of Diets | Sustainable diets are important to mitigating anthropogenic climate change | Mazac et al., 2023 |

One-Health Benefit of PBDs

The One-Health model states that the health of soil, plants, animals, people, ecosystems and planetary processes is strongly inter-connected. The One-Health model is gaining momentum among agronomists, veterinarians, human nutritionists, and those concerned with planetary health. The data in Table 3 outlines examples of the PBDs which also support the One-Health model as confirmed through diverse approaches including LCA, cohort and randomized control trials of diverse and well-planned diets.

The benefits of PBDs to human health can be enhanced by diversification of diet from traditional crops or forgotten crops of the specific region. Nutrient dense traditional crops include cereals (sorghum, millet, teff), pulses (chickpeas, mung beans, pigeon peas, lentils), root crops (cassava, yam, sweet potato, taro) and some supplements such as algal products. These traditional crops are dense in essential plant nutrients and other health-positive ingredients. Indeed, well-planned PBDs can lead to multiple benefits to human and nature.

Table 3. One-Health Benefits of PBDs

| Approach | Beneficial Impact | References |

|---|---|---|

| Life Cycle Analysis | Animal welfare and human health indicators must be included in LCA | Paris et al., 2022 |

| Veganism | Addresses simultaneously issues of food, health, climate change, and animal justice with better physical and mental health, and healthier masculinities in men | Aavik and Velgan, 2021 |

| Vegetarian diets | Can effectively prevent hypertension, metabolic diseases such as diabetes and obesity, and certain cancers. Long-term vegan meditation can improve body’s immunity and adjusting endocrine and metabolic levels, and good health | Jia et al., 2020 |

| Cohort and randomized control trials | PBD diets have beneficial impacts on obesity control, cardiovascular health, and diabetes prevention | Viroli et al., 2023 |

| Traditional crops | Chickpea and other traditional crops (pulses) lead to better nutrition and health | Bar-El Dadon et al., 2017 |

| Algal supplementation | Long chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid deficiencies in vegetarian population can be addressed by using algal supplements | Craddock et al., 2017 |

| Well-planned vegetarian diet | A holistic approach leading to a wide range of plant foods along with a consistent source of vitamin B12, can provide adequate nutrition | Agnoli et al., 2017 |

Some Nutritional Constraints of PBDs

Despite numerous benefits of transitioning to PBDs, there are some concerns regarding the risks of micronutrient deficiencies and the attendant human health issues of PBDs which are neither properly planned nor adequately balanced. Important among these concerns (Table 4) are food allergy, low digestibility, existence of some anti-nutritional compounds, risks of kidney disease in some leafy vegetables which may contain substances that aggravate formation of kidney stones, and toxicity of some substances such as Mn concentration in açaí.

Education about these issues, judicious planning of PBDs, increasing diversity of sources of PBDs including the use of traditional crops, and consultation with specialists in human nutrition can be advantageous to human wellbeing.

Table 4. Health risks of PBDs and environmentally sustainable foods

| Causes of Malnutrition in PBDs | References |

|---|---|

| Lack of essential macro- and micro-nutrients; nutrient deficiencies and risks of non-communicable diseases, deficiency of Fe and Zn | Kalmpourtzidou and Scazzina, 2022; Metoudi et al., 2024 |

| Food allergy with PBD | Protudjer et al., 2024 |

| Low digestibility coefficient for protein and deficiency of amino acids | Adolph, 1954 |

| Existence of anti-nutrient compounds like phytic acid and polyphenols which reduce the mineral bioavailability because of their chelating properties such as in Pearl Millet | Singhal et al., 2022 |

| Risks of high protein intake in some PBD (e.g., pulses) may accelerate underlying kidney disease process | Bernstein et al., 2007 |

| A daily consumption of 300 ml açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) may lead to daily intake of Mn (14.6 mg) which exceeds the recommended dose at 11 mg, and it leads to impaired Fe absorption and anemia in children | Santos et al., 2014 |

Planetary Benefits of PBDs

Over and above the benefits to human health and wellbeing, there are also distinct planetary benefits of transitioning to PBDs. Planetary health can be improved by using PBDs which have low CFP, including diverse sources of food (traditional crops of the region along with some pulses), and addressing the problem of malnutrition because of the deficiency of some micronutrients (e.g., Zn, Fe) in PBDs (Table 5).

Table 5. Planetary benefits of PBD

| Approach | Impact | References |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Foot-Print | Diets that exhibit low CFPs (e.g., vegan, climatarian, Mediterranean) have a positive effect on human health | Dixon et al., 2023 |

| Planning | Well-planned PBD is achievable and sustainable in a community setting and has health benefits | Sadler et al., 2024 |

| Dietary Patterns | There is a strong link between dietary patterns (e.g., vegetarian diet) and improved health | Orlich and Fraser, 2014 |

| Addressing Malnutrition | PBDs (along with use of pulses and traditional crops) can achieve a malnutrition-free world while providing significantly higher intake of ascorbate, folate, magnesium, copper, and manganese | Kumar et al., 2023 |

Processes are reducing CFP, decreasing emission of GHGs, increasing above and below-ground biodiversity, sparing land and water, and reducing risks of degradation of soil (i.e., erosion, elemental imbalance, loss of soil organic matter content, decline in soil structure), eutrophication of water, and pollution of air.

General Considerations

An objective assessment of PBDs for human and planetary health needs careful assessment of the following:

1. Health Impacts of Plant-Based Diets

PBDs are receiving a lot of attention and more visibility because of their potential for health benefits and possibility of positive environmental impacts. PBDs contain some ingredients which may have some independent health benefits. Several studies have indicated that PBDs can reduce risks of developing diabetes, hypertension, CVDs, dementia and some cancers. Vegetarian diets are also associated with reduction in weight, blood pressure, glycosylated hemoglobin for low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Beneficial impacts of PBDs are due to low intakes of saturated fats and high intakes of dietary fibers.

However, potentially deleterious effects of PBDs are due to lack of some micronutrients, vitamin D, and B12, Ca, Fe, Zn and I. PBDs lead to smaller risk reduction in CVDs, diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease. Yet, there are limited data for cancer and CVDs. PBDs may also adversely affect bone-mineral density and risks of lumbar fracture and bone health.

Effects of PBDs on quality of life (physical, psychological, social, and environmental) are not widely studied. The choice of adopting PBDs may have positive impacts such as improved physical health, positive feelings related to morally-correct attitude, an increased sense of belonging to a wider community, and lower EFP.

But there may also be some negative impacts of adopting PBDs on quality of life such as environment, social/cultural group, gender-based differences, economic status, and a limited access to PBDs.

Adoption of PBDs may also lead to higher levels of pesticides in consumers suggesting that consumption of organic produce may reduce exposure.

Organophosphate pesticide residues in vegetarians.

In comparison with ABDs, vegetarians are known to have a lower mean body mass index or BMI (in kg/m²), a lower mean plasma total concentration (in 0.5 mmol/l), and a lower mortality from coronary artery disease (~25%). Those following PBDs may also have lower risks of some other diseases, gallstones and appendicitis. However, there may be no differences in mortality from common cancers. There is a lack of information about an association between PBDs and cancer prevention.

2. Environmental Impacts of Plant-Based Diets

In general, PBDs are less resource-intensive and have lower EFP than those of ABDs. In other words, PBDs are more environmentally sustainable than are ABDs. Thus, adopting PBDs high in fiber may reduce global warming and prevalence of obesity and other diseases. However, long-distance air transport, deep freezing, and some horticultural practices may increase EFP of PBDs.

GHG emissions from PBDs may be 35 to 50% lower than those for ABDs with attendant impacts on the use of natural resources. The GWP impacts of ABDs can be substantially more than those of PBDs, and environmental indicators show a positive association with the amount of PBDs consumed. Emission of GHGs may be reduced by more than two-fold for PBDs (0.9 kg) compared with that of ABDs (2.1 kg CO₂ equivalent per meal). Thus, changing from ABDs to PBDs may reduce the EFP due to climate change, eco-toxicity, acidification, and eutrophication. Food waste may also be lower in PBDs than with ABDs.

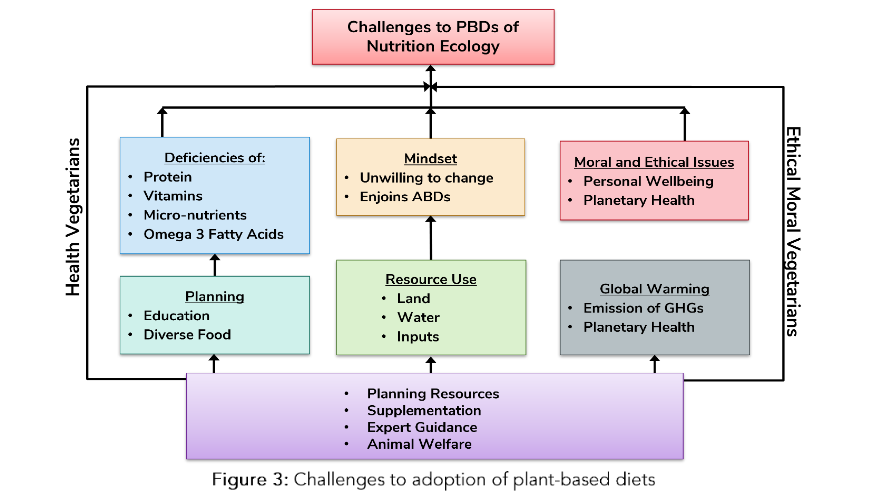

3. Challenges to Promoting PBDs in Developed Economies

Interdisciplinary scientific discipline of nutrition ecology is pertinent to addressing the global issues of human and planetary health. Despite substantial benefits, both in terms of health and environmental impacts, ABDs may be more attractive to consumers than PBDs. The more restrictive the PBD and the younger the child, the greater the risks of nutritional deficiency of protein quantity and quality, Fe, Zn, Se, Ca, riboflavin, vitamins A, D, B12 and essential fatty acids.

Thus, adequate planning is critical to reducing health-related risks of PBDs. Well-planned PBDs must include numerous protective fibers (i.e., fiber, phytocompounds) and carefully chosen diverse sources including pulses and nuts. The choice of personal vs. planetary health is also a moral and ethical issue.

Primary barriers to adopting PBDs include the mindset about enjoying eating ABDs and unwillingness to change eating habits. In addition, PBDs also have health risks of deficiencies of protein, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin D, vitamin B12, Fe, Ca, and Zn. Restrictive and unbalanced PBDs may lead to nutritional deficiencies, especially in situations of high metabolic demand. A complete PBD in a young child would need substantial commitment, expert guidance, planning, resources, and supplementation. Similar precautions are needed for pregnant women. There is also a question of “health vegetarian” versus “ethical vegetarian.” The former is motivated by the perceived threat of disease and the latter by animal welfare and planetary health. These issues must be critically considered (Figure 3).

Conclusions

Humanity is at a critical crossroads of growing and increasingly affluent population, anthropogenic global warming, and widespread problems of undernutrition and malnutrition. These problems are being aggravated by natural and political causes which have led to disruptions in food production and supply chains, as well as decreased the amount and quality of food produced from agro-ecosystems.

Thus, the choice of diet must be made in view of its impact on resources needed to produce food (soil, water, inputs, energy), EFP, and risks of non-communicable diseases (e.g., obesity, diabetes, some cancers) which are being aggravated by excessive reliance and indiscriminate use of ABDs. Choice of diet is also a moral question of personal or planetary benefits.

Because there are several types of PBDs, adequate planning is needed with regards to:

a) diversity of food sources (traditional crops, pulses, and some algal-based supplements),

b) advice of specialists in human nutrition,

c) guidance from scientists in management of natural resources (i.e., soil scientists, hydrologists, plant scientists),

d) education of mothers and planners about the strategies of reducing risks of malnutrition caused by deficiency of micronutrients (Zn, Fe) in PBDs, and

e) interaction with policy makers to promote adoption of PBDs.

The risks of deficiency of micronutrients with some PBDs are aggravated by low digestibility and low density of some critical nutrients in predominantly cereal-based diets (rice, wheat). Thus, a judicious choice of appropriate PBDs, in combination with diverse sources which include traditional crops and pulses and some supplements, can enhance human health and address some critical planetary processes through sparing of some land and water for nature.

References

1. Lal R. The soil-peace nexus: our common future. SOIL SCIENCE AND PLANT NUTRITION. 2015;61(4):566-578. doi:10.1080/00380768.2015.1065166

2. Aavik K, Velgan M. Vegan Men’s Food and Health Practices: A Recipe for a More Health-Conscious Masculinity? AMERICAN JOURNAL OF MENS HEALTH. 2021;15(5). doi:10.1177/15579883211044323

3. Coelho C, Pernollet F, van der Werf H. Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of Diets with Improved Omega-3 Fatty Acid Profiles. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(8). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0160397

4. Viroli G, Kalmpourtzidou A, Cena H. Exploring Benefits and Barriers of Plant-Based Diets: Health, Environmental Impact, Food Accessibility and Acceptability. NUTRIENTS. 2023;15(22).

doi:10.3390/nu15224723

5. Paris J, Escobar N, Falkenberg T, et al. Optimised diets for achieving One Health: A pilot study in the Rhine-Ruhr Metropolis in Germany. ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT REVIEW. 2024;106. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2024.107529

6. Satija A, Hu F. Plant-based diets and cardiovascular health. TRENDS IN CARDIOVASCULAR MEDICINE. 2018;28(7):437-441. doi:10.1016/j.tcm.2018.02.004

7. van Vliet S, Kronberg S, Provenza F. Plant-Based Meats, Human Health, and Climate Change. FRONTIERS IN SUSTAINABLE FOOD SYSTEMS. 2020;4. doi:10.3389/fsufs.2020.00128

8. Hagmann D, Siegrist M, Hartmann C. Meat avoidance: motives, alternative proteins and diet quality in a sample of Swiss consumers. PUBLIC HEALTH NUTRITION. 2019;22(13):2448-2459. doi:10.1017/S1368980019001277

9. Moreno L, Meyer R, Donovan S, et al. Perspective: Striking a Balance between Planetary and Human Health-Is There a Path Forward? ADVANCES IN NUTRITION. 2022;13(2):355-375. doi:10.1093/advances/nmab139

10. Protudjer J, Roth-Walter F, Meyer R. Nutritional Considerations of Plant-Based Diets for People With Food Allergy. CLINICAL AND EXPERIMENTAL ALLERGY. 2024;54(11):895-908. doi:10.1111/cea.14557

11. Jia W, Zhen J, Liu A, et al. Long-Term Vegan Meditation Improved Human Gut Microbiota. EVIDENCE-BASED COMPLEMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE. 2020;2020. doi:10.1155/2020/9517897

12. van Lettow M, Fawzi W, Semba R. Triple trouble: The role of malnutrition in tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus co-infection. NUTRITION REVIEWS. 2003;61(3):81-90. doi:10.1301/nr.2003.marr.81-90

13. Majumdar A, Shukla S, Pandey R. Culinary and herbal resources as nutritional supplements against malnutrition-associated immunity deficiency: the vegetarian review. FUTURE JOURNAL OF PHARMACEUTICAL SCIENCES. 2020;6(1). doi:10.1186/s43094-020-00067-5

14. Merli M, Iebba V, Giusto M. What is new about diet in hepatic encephalopathy. METABOLIC BRAIN DISEASE. 2016;31(6):1289-1294. doi:10.1007/s11011-015-9734-5

15. Kumar S, Gopinath K, Sheoran S, et al. Pulse-based cropping systems for soil health restoration, resources conservation, and nutritional and environmental security in rainfed agroecosystems. FRONTIERS IN MICROBIOLOGY. 2023;13. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2022.1041124

16. Rancilio G, Gibin D, Blaco A, Casagrandi R. Low-GHG culturally acceptable diets to reduce individual carbon footprint by 20%. JOURNAL OF CLEANER PRODUCTION. 2022;338. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.130623

17. Martin M, Brandao M. Evaluating the Environmental Consequences of Swedish Food Consumption and Dietary Choices. SUSTAINABILITY. 2017;9(12). doi:10.3390/su9122227

18. Stoll-Kleemann S, Schmidt U. Reducing meat consumption in developed and transition countries to counter climate change and biodiversity loss: a review of influence factors. REGIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE. 2017;17(5):1261-1277. doi:10.1007/s10113-016-1057-5

19. Mayes X, Informat Resources Management Assoc. Livestock and Climate Change: An Analysis of Media Coverage in the Sydney Morning Herald.; 2017:1246. doi:10.4018/978-1-5225-0803-8.ch059

20. Kheirinejad S, Bozorg-Haddad O, Savic D, Singh V, Loáiciga H. Developing a National-Scale Hybrid System Dynamics, Agent-Based, Model to Evaluate the Effects of Dietary Changes on the Water, Food, and Energy Nexus. WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT. 2024;38(10):3581-3606. doi:10.1007/s11269-024-03829-5

21. Mazac R, Järviö N, Tuomisto H. Environmental and nutritional Life Cycle Assessment of novel foods in meals as transformative food for the future. SCIENCE OF THE TOTAL ENVIRONMENT. 2023;876. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162796

22. Bar-El Dadon S, Abbo S, Reifen R. Leveraging traditional crops for better nutrition and health – The case of chickpea. TRENDS IN FOOD SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY. 2017;64:39-47. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2017.04.002

23. Craddock J, Neale E, Probst Y, Peoples G. Algal supplementation of vegetarian eating patterns improves plasma and serum docosahexaenoic acid concentrations and omega-3 indices: a systematic literature review. JOURNAL OF HUMAN NUTRITION AND DIETETICS. 2017;30(6):693-699. doi:10.1111/jhn.12474

24. Agnoli C, Baroni L, Bertini I, et al. Position paper on vegetarian diets from the working group of the Italian Society of Human Nutrition. NUTRITION METABOLISM AND CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASES. 2017;27(12):1037-1052. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2017.10.020

25. Paris J, Falkenberg T, Nöthlings U, Heinzel C, Borgemeister C, Escobar N. Changing dietary patterns is necessary to improve the sustainability of Western diets from a One Health perspective. SCIENCE OF THE TOTAL ENVIRONMENT. 2022; 811. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151437

26. Kalmpourtzidou A, Scazzina F. Changes in terms of risks/benefits of shifting diets towards healthier and more sustainable dietary models. EFSA JOURNAL. 2022;20. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2022.e200904

27. Metoudi M, Bauer A, Haffner T, Kassam S. A cross-sectional survey exploring knowledge, beliefs and barriers to whole food plant-based diets amongst registered dietitians in the United Kingdom and Ireland. JOURNAL OF HUMAN NUTRITION AND DIETETICS. Published online November 3, 2024. doi:10.1111/jhn.13386

28. ADOLPH W. NUTRITION PROBLEMS IN TROPICAL AREAS. AMERICAN JOURNAL OF TROPICAL MEDICINE AND HYGIENE. 1954;3(6): 964-970. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1954.3.964

29. Singhal T, Satyavathi C, Singh S, et al. Achieving nutritional security in India through iron and zinc biofortification in pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br.). PHYSIOLOGY AND MOLECULAR BIOLOGY OF PLANTS. 2022;28(4):849-869. doi:10.1007/s12298-022-01144-0

30. Bernstein A, Treyzon L, Li Z. Are high-protein, vegetable-based diets safe for kidney function? A review of the literature. JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN DIETETIC ASSOCIATION. 2007; 107(4):644-650. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2007.01.002

31. Santos V, Teixeira G, Barbosa F. ACAI (Euterpe oleracea MART.): A TROPICAL FRUIT WITH HIGH LEVELS OF ESSENTIAL MINERALS-ESPECIALLY MANGANESE-AND ITS CONTRIBUTION AS A SOURCE OF NATURAL MINERAL SUPPLEMENTATION. JOURNAL OF TOXICOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH-PART A-CURRENT ISSUES. 2014;77(1-3):80-89. doi:10.1080/15287394.2014.866923

32. Dixon K, Michelsen M. Modern Diets and the Health of Our Planet: An Investigation into the Environmental Impacts of Food Choices. NUTRIENTS. 2023;15:692. doi:10.3390/nu15030692

33. Sadler I, Bauer A, Kassam S. Dietary habits and self-reported health outcomes in a cross-sectional survey of health-conscious adults eating a plant-based diet. JOURNAL OF HUMAN NUTRITION AND DIETETICS. 2024;37(4):1061-1074. doi:10.1111/jhn.13321

34. Orlich M, Fraser G. Vegetarian diets in the Adventist Health Study 2: a review of initial published findings. AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CLINICAL NUTRITION. 2014;100(1):353S-358S. doi:10.3945/ajcn.113.071233

35. Craig, W J. Health effects of vegan diets. THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CLINICAL NUTRITION. 2009; 89(5), 1627S-1633S.

36. McEvoy C, & Woodside J V. Vegetarian and vegan diets: weighing the claims. NUTRITION GUIDE FOR PHYSICIANS. 2010; 81-93.

37. McEvoy C T, Temple N, & Woodside J V. Vegetarian diets, low-meat diets and health: a review. PUBLIC HEALTH NUTRITION. 2012;15(12), 2287-2294.

38. Marsh K, Zeuschner C, & Saunders A. Health implications of a vegetarian diet: a review. AMERICAN JOURNAL OF LIFESTYLE MEDICINE. 2012; 6(3), 250-267.

39. Tuso P J, Ismail M H, Ha B P, & Bartolotto C. Nutritional update for physicians: plant-based diets. THE PERMANENTE JOURNAL. 2013; 17(2), 61.

40. Hargreaves S M, Raposo A, Saraiva A, & Zandonadi R P. Vegetarian diet: an overview through the perspective of quality of life domains. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCH AND PUBLIC HEALTH. 2021; 18(8), 4067.

41. Wang T, Masedunskas A, Willett W C, & Fontana L. Vegetarian and vegan diets: benefits and drawbacks. EUROPEAN HEART JOURNAL. 2023; 44(36), 3423-3439.

42. Key T J, Papier K, & Tong T Y. Plant-based diets and long-term health: findings from the EPIC-Oxford study. PROCEEDINGS OF THE NUTRITION SOCIETY. 2022; 81(2), 190-198.

43. Rocha J P, Laster J, Parag B, & Shah N U. Multiple health benefits and minimal risks associated with vegetarian diets. CURRENT NUTRITION REPORTS. 2019; 8, 374-381.

44. Chuang T L, Lin C H, & Wang Y F. Effects of vegetarian diet on bone mineral density. TZU CHI MEDICAL JOURNAL. 2021; 33(2), 128-134.

45. Berman T, Göen T, Novack L, Beacher L, Grinshpan L, Segev D, & Tordjman K. Urinary concentrations of organophosphate and carbamate pesticides in residents of a vegetarian community. ENVIRONMENT INTERNATIONAL. 2016; 96, 34-40.

46. Key T J, Davey G K, & Appleby P N. Health benefits of a vegetarian diet. PROCEEDINGS OF THE NUTRITION SOCIETY. 1999; 58(2), 271-275.

47. Reijnders L, & Soret S. Quantification of the environmental impact of different dietary protein choices. THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CLINICAL NUTRITION. 2003; 78(3), 664S-668S.

48. Fresán U, & Sabaté J. Vegetarian diets: planetary health and its alignment with human health. Advances in nutrition. 2019; 10, S380-S388.

49. Kelhafiz I “A Comparison of Environmental Impacts of Different Nutritional Diets via Life Cycle Assessment” in PROCEEDINGS OF THE 6TH EURASIA WASTE MANAGEMENT SYMPOSIUM, EWMS 2022. p. 432. Esenler/Istanbul: Mehmet Sinan Bilgili.

50. Góralska-Walczak R, Kopczyńska K, Kazimierczak R, Stefanovic L, Bieńko M, Oczkowski M, & Średnicka-Tober D. Environmental Indicators of Vegan and Vegetarian Diets: A Pilot Study in a Group of Young Adult Female Consumers in Poland. SUSTAINABILITY. 2023; 16(1). http://dx-doi-org.proxy.lib.ohio-state.edu/10.3390/su16010249

51. Medawar E, Zedler M, de Biasi L, Villringer A, & Witte A V. Effects of single plant-based vs. animal-based meals on satiety and mood in real-world smartphone-embedded studies. NPJ SCIENCE OF FOOD. 2023; 7(1), 1.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-022-00176-w

52. Kusch S, & Fiebelkorn F. Environmental impact judgments of meat, vegetarian, and insect burgers: Unifying the negative footprint illusion and quantity insensitivity. FOOD QUALITY AND PREFERENCE. 2019; 78.

doi:10.1016/J.FOODQUAL.2019.103731

53. Krpan D, & Houtsma N. To veg or not to veg? The impact of framing on vegetarian food choice. JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY. 2020; 67, doi:10.1016/J.JENVP.2020.101391

54. Chai B C, van der Voort J R, Grofelnik K, Eliasdottir H G, Klöss I, & Perez-Cueto F. Which diet has the least environmental impact on our planet? A systematic review of vegan, vegetarian and omnivorous diets. SUSTAINABILITY. 2019;11 (15), 4110. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154110

55. Rabès A, Seconda L, Langevin B, Allès B, Touvier M, Hercberg S, Lairon D, Baudry J, Pointereau P, Kesse-Guyot E. Greenhouse gas emissions, energy demand and land use associated with omnivorous, pesco-vegetarian, vegetarian, and vegan diets accounting for farming practices. SUSTAINABLE PRODUCTION AND CONSUMPTION. 2020 Apr 1;22:138-46.

56. Berardy A, Egan B, Birchfield N, Sabaté J, & Lynch H. Comparison of Plate Waste between Vegetarian and Meat-Containing Meals in a Hospital Setting: Environmental and Nutritional Considerations. NUTRIENTS. 2022; 14(6), 1174. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14061174

57. Scarborough P, Clark M, Cobiac L, Papier K, Knuppel A, Lynch J, Harrington R, Key T, Springmann M. Vegans, vegetarians, fish-eaters and meat-eaters in the UK show discrepant environmental impacts. NATURE FOOD. 2023 Jul;4(7):565-74.

58. Dahmani J, Nicklaus S, Grenier JM, Marty L. Nutritional quality and greenhouse gas emissions of vegetarian and non-vegetarian primary school meals: A case study in Dijon, France. FRONTIERS IN NUTRITION. 2022 Oct 10;9:997144.

59. Leitzmann C. Nutrition ecology: the contribution of vegetarian diets. THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CLINICAL NUTRITION. 2003; 78(3), 657S-659S. doi:10.1093/AJCN/78.3.657S

60. Pechey R, Hollands G J, & Marteau T M. Are meat options preferred to comparable vegetarian options? An experimental study. BMC RESEARCH NOTES. 2021; 14(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-021-05451-9

61. Kiely M E. Risks and benefits of vegan and vegetarian diets in children. THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE NUTRITION SOCIETY. 2021; 80(2), 159-164. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002966512100001X

62. Shreedhar G, & Galizzi M M. Personal or planetary health? Direct, spillover and carryover effects of non-monetary benefits of vegetarian behaviour. JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY. 2021; 78.

doi:10.1016/J.JENVP.2021.101710

63. Lea E, & Worsley A. Benefits and barriers to the consumption of a vegetarian diet in Australia. PUBLIC HEALTH NUTRITION. 2003; 6(5), 505-11. https://doi.org/10.1079/PHN2002452

64. Sabaté J. The contribution of vegetarian diets to health and disease: a paradigm shift? THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CLINICAL NUTRITION. 2003; 78(3), 502S-507S. doi:10.1093/AJCN/78.3.502S

65. Alexy U. Diet and growth of vegetarian and Vegan children. BMJ NUTRITION. 2023; Prevention & Health, 6(Suppl 2).

66. Mangels A R. Vegetarian diets in pregnancy. HANDBOOK OF NUTRITION AND PREGNANCY. 2008; 215-231.

67. Jabs J, Devine C M, & Sobal J. Model of the process of adopting vegetarian diets: Health vegetarians and ethical vegetarians. JOURNAL OF NUTRITION EDUCATION. 1998; 30(4), 196-202.