Breast Cancer: Omission of Axillary Node Surgery

Selection of Breast Cancer Patients for Omission of Axillary Lymph Node Surgery

Jenny Bui, MD, MPH¹; S. David Nathanson, MD¹; Christine Joliat, MD¹; Jessica Bensenhaver, MD, MS¹; Theresa L. Schwartz, MD, MS¹; Lindsay Petersen, MD¹; Anna Lehrberg, DO¹; Laura Dalla Vecchia, MD¹

- Department of Surgery, Henry Ford Health, Detroit, Michigan

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED:30 October 2024

CITATION: Bui, J., et al., 2024. Selection of Breast Cancer Patients for Omission of Axillary Lymph Node Surgery.

Medical Research Archives, [online] 12(10).

https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v12i11.5861

COPYRIGHT:© 2024 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v12i11.5861

ISSN: 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Accurate axillary lymph node dissection (CALND), defined as the removal of all lymph nodes from levels I and II, has been the standard for clinically confirmed lymph node (LN) metastases, or prophylactic for clinically negative LNs, and was once a routine part of the standard surgical management for patients with breast cancer (BC). In 1977, the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) B-04 trial called into question the therapeutic value of CALND in early BC with clinically negative ALNs. In this landmark trial, patients were randomized to radical mastectomy, total mastectomy with LN irradiation, or the mastectomy without any surgical intervention. The ultimate goal is to eliminate axillary surgery altogether in some patients. However, some patients’ outcomes depend upon excision of the axilla. This review aims to summarize the current recommendations for the omission of axillary lymph node surgery.

Keywords

breast cancer, axillary lymph node dissection, sentinel lymph node biopsy, metastasis, surgical management

Introduction

Complete axillary lymph node dissection (CALND), defined as the removal of axillary lymph nodes (ALNs) from levels I and II, either therapeutic for clinically confirmed lymph node (LN) metastases, or prophylactic for clinically negative LNs was once a routine part of the standard surgical management for patients with breast cancer (BC). In 1977, the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) B-04 trial called into question the therapeutic value of CALND in early BC with clinically negative ALNs.¹ In this landmark trial, patients were randomized to radical mastectomy, total mastectomy with LN irradiation, or total mastectomy with delayed CALND if nodal disease developed. After 25 years of follow-up, it was shown that there were no survival differences among the groups. In the observation arm, only 18.5% of patients developed axillary recurrence, despite a calculated likelihood that 40% would have had nodal metastases, suggesting that in more than 50% of the cases the LN metastases did not progress.¹

These studies demonstrated success in improvement in locoregional control by adjuvant systemic therapies compared to surgery alone. In the NSABP B-14 trial, endocrine therapy with Tamoxifen significantly lowered the locoregional recurrence rate in estrogen receptor–positive women from 14.7% to 4.3%.² Similarly, the NSABP B-13 trial showed that chemotherapy reduced locoregional recurrence in estrogen receptor–negative women from 13.4% to 2.6%.³ This trend was further confirmed in the NSABP B-31 trial, where combining the anti-HER2/neu antibody trastuzumab with chemotherapy in HER2/neu-overexpressing BC patients led to enhanced local control.⁴

Other advances in adjuvant therapies confirmed the hypothesis that LN metastases can be eradicated without surgery.⁵ ⁶ Following the introduction of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) as a diagnostic rather than a therapeutic procedure in the 1990s, the CALND has been largely replaced.⁷ ¹² While SLNB is less invasive and poses fewer complications compared to CALND, there is a growing trend toward de-escalation of axillary management in BC treatment. The ultimate goal is to eliminate axillary surgery altogether in select patients. However, some treatment decisions still depend upon excision of the SLNs.⁷–¹⁰ ¹³ In addition, there are some patients with more advanced BCs with LN metastases that still warrant CALND.⁷ ¹⁰ ¹⁴ ¹⁵

In an age where each BC patient deserves a careful personalized plan of management that conforms to the current guidelines, the type of ALN surgery is an important area of investigation. The selection of the type of LN surgery should include accounting for surgical morbidity, demographics, the patient’s quality of life, the expected treatment outcomes, molecular subtype, pathological factors, a deeper understanding of tumor biology, and improved means of evaluating the tumor status of regional LNs.

In this paper, we will discuss recent advances in the detection of LN metastases by imaging modalities (IM), the indications and outcomes of omitting SLNB, the rationale behind these decisions, and the potential impact on patient outcomes. By focusing on evidence-based practices and recent clinical trials, we provide an overview of this evolving aspect of BC management, ultimately contributing to more effective and less invasive treatment pathways for patients.

Nonsurgical Evaluation of Ipsilateral Axillary Lymph Nodes

Nonsurgical evaluation of ipsilateral ALNs in BC patients adds accuracy to preoperative staging and treatment planning. Techniques such as ultrasound (US), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET), and computed tomography (CT) are increasingly used to assess LN involvement.¹⁶–²¹

Ultrasound, often combined with fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) or core needle biopsy (CNB), allows for real-time imaging and cytological/histological evaluation.¹⁷ Ultrasound combined with elastography enhances the specificity of the imaging.

enabling clinicians to not only identify suspicious LNs, but also to possibly justify the avoidance of invasive surgery.²³

Ultrasound is the preferred ALN imaging modality for primary BC while MRI, PET and CT may be reserved for staging purposes or in cases where more extensive disease is suspected. Compared with clinical examination, axillary US has a significantly higher negative predictive value (76%–84% for US vs. 50%–62% for clinical examination).²⁴ Sonographic criteria of possible LN metastatic disease include cortical thickening greater than 3 mm, loss of the fatty hilum, changed LN shape, increased vascularity, and irregular cortical bulges.²⁵ ²⁶ Ipsilateral axillary US is commonly performed when LNs appear abnormal on mammogram, when ipsilateral invasive BCs are larger than 2 centimeters, for clinically palpable nodes, or for meeting the SOUND trial criteria for deferring SLNB²⁷ (patient aged greater than 50 years old, tumor size less than 2 cm, hormone receptor positive, and more than 2 mm).²⁷

Breast MRI is effective in assessing the size and anatomical extent of ipsilateral ALNs while allowing for immediate comparison with the opposite side. However, its specificity in diagnosing LN metastases is low, which limits its accuracy. Furthermore, the potential discomfort and high costs associated with MRIs make them less practical for routine clinical use, especially when other less invasive and more cost-effective diagnostic methods are available. For these reasons, despite its imaging capabilities, MRI might not always be the most suitable option for evaluating LNs in clinical settings.¹⁸ ¹⁹

PET with or without CT scans can be valuable for identifying metabolic activity in ALNs, offering insights into the possibility that enlarged nodes harbor malignant tumors. However, they have limitations in differentiating between malignant tumors and benign conditions that also cause increased metabolic activity. These conditions include lymphoproliferative responses due to tumor in the primary breast site, recent surgical intervention, inflammation, vaccination, immunotherapy, or infection.²⁰ ²¹ Therefore, while PET-CT is useful in evaluating ALNs, observed abnormalities must be interpreted with caution and often need confirmation through additional diagnostic methods like tissue biopsy.

Axillary Imaging as an Alternative to Axillary Lymph Node Surgery

Although not currently an absolute guideline, axillary US is selectively recommended for patients with BC to evaluate ALN status preoperatively. The SOUND trial has shown that negative axillary US in small early BCs is noninferior to performing a SLNB. Other studies have demonstrated that some sonographic features of breast lesions, such as tumor size, margin morphology, and location might be associated with BC nodal metastases and thus can help predict ALN status.²⁶ ²⁸ Risk models have also been developed for predicting ALN metastases in patients with BC.²⁹–³² As imaging modalities improve and more nomograms are developed, US and other imaging modalities may help to further de-escalate ALN surgery.

Confirming the Diagnosis of Clinically Positive Lymph Nodes

Neoadjuvant systemic therapy, including chemotherapy (NAC), anti-HER2/neu or other targeted therapy, immunotherapy or hormonal therapy is often used in patients with proven LN metastases. In BC patients with clinically or radiologically suspicious LNs, the choice between FNAB and CNB for cytological proof of LN metastases is an important consideration that can impact treatment decisions and patient outcomes.

Fine needle aspiration biopsy is a quick, minimally invasive procedure that involves using a thin, hollow needle to extract a small sample of cells from the LN. However, FNAB provides only cellular material and may not yield enough tissue for comprehensive histopathological evaluation, particularly for determining receptor (hormone receptors and HER2/neu) status. It may also have a higher false-negative rate compared to CNB.³³ ³⁴ Core needle

biopsy offers more comprehensive diagnostic information. Core needle biopsy uses a larger, hollow needle to obtain a tissue core from the LN, allowing for a more detailed pathological analysis, including receptor status and tumor grade. Of note, whenever a LN is biopsied, it is important to leave a metal clip in the node as a guide for the surgeon for future removal by targeted axillary dissection.³⁵

Current Recommendations for Axillary Lymph Node Surgery

EARLY CLINICALLY cN0 INVASIVE BREAST CANCER

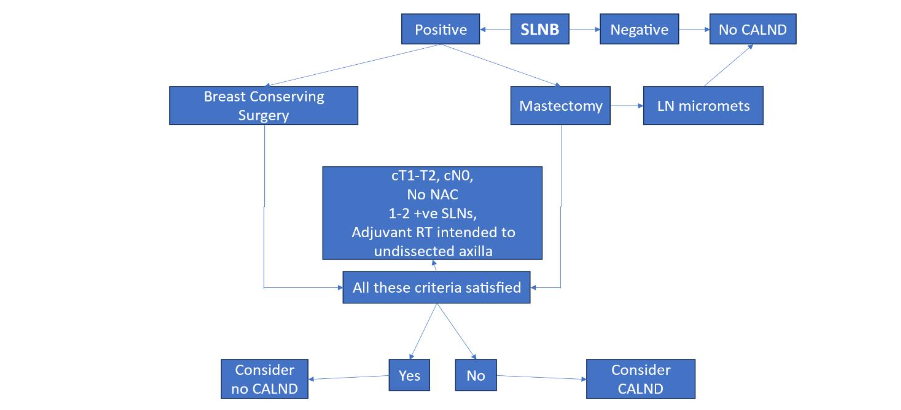

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network, American Society of Clinical Oncology, American Society of Breast Surgeons, and Society of Surgical Oncology recommend eligible patients with early-stage BC undergo an operative axillary evaluation to determine the presence of LN metastasis.⁷–¹⁰ Clinically node-negative patients (cN0) should be offered axillary evaluation by SLNB (Figure 1). If SLNs exhibit metastatic BC in less than 3 LNs and without extra-nodal invasion, clinical studies support avoiding CALND,³⁶ ³⁸ provided that regional radiation and systemic therapies are also added as appropriate (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Summary of Axillary Lymph Node Management for Breast Cancer

-

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is the preferred method. ⁷ ¹⁰

-

Level III dissection only when there is gross tumor in level II or III nodes.

-

See Figures 2 and 3 for indications for complete axillary lymph node dissection.

-

Optional criteria for omission of SLNB:

-

Pathologically favorable tumors

-

Selection of systemic and/or radiation is unlikely to be affected

-

≥ 70 years of age³⁹

-

Serious comorbid conditions

-

The SOUND criteria (> 50 years of age, hormone receptor positive, ≤ 2 cm in size, Ki 67 < 20%, and negative axillary US)²⁷

-

Figure 2. Management of clinically negative ipsilateral axillary nodes in breast cancer.

⁸ Abbreviations: CALND, complete axillary lymph node dissection; LN micromets, lymph node micrometastases; NAC, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; RT, radiation therapy; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy

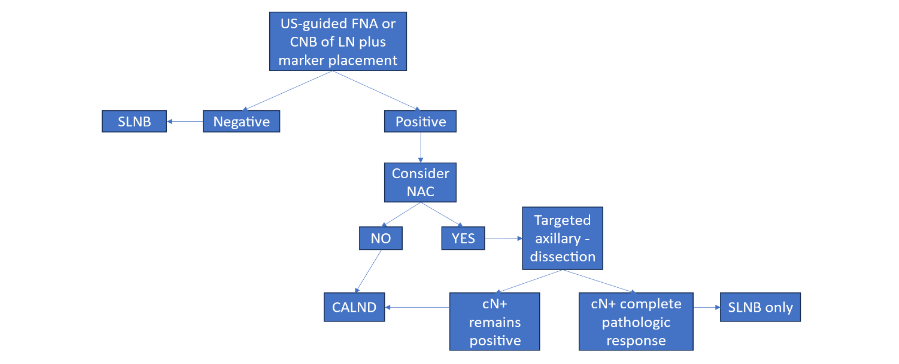

CLINICALLY NODE-POSITIVE BREAST CANCER

National Comprehensive Cancer Network, American Society of Clinical Oncology, American Society of Breast Surgeons, and Society of Surgical Oncology recommend patients who present with clinically node-positive involvement undergo CALND as part of their surgical management, regardless of their treatment approach with NAC or adjuvant chemotherapy.⁷–¹⁰ As an alternative to CALND for patients receiving NAC, plus other systemic therapies, targeted ALN dissection should be considered.⁴⁰–⁴³ The objective of this operative procedure is to remove the LN that showed metastasis on needle biopsy prior to NAC. The LN is identified intraoperatively by finding the clipped LN by a radiologically placed identifier, such as a preoperatively placed wire, or an intraoperatively traceable radioactive seed, bead, or solution.⁴¹,⁴³,⁴⁶ Initial clinical studies, such as the Alliance Z001 trial, suggest it is reasonable to consider omission of CALND if the histology shows a complete pathological response with no residual tumor in the node.¹³

Patients with residual LN tumor after neoadjuvant therapy are usually offered level I–II CALND, although an alternative option might be axillary radiation (Figure 2). When compared to CALND, the AMAROS study showed comparable results with axillary irradiation.³⁷ The AMAROS trial showed that it was safe to avoid CALND in selected patients with 1 or 2 positive SLNs who had received adjuvant axillary radiation therapy.³⁷

INFLAMMATORY BREAST CANCER

Inflammatory BC, an aggressive form of BC, is usually managed by NAC, surgery, and radiation therapy. The decision regarding CALND is an important aspect in treatment planning for patients with inflammatory BC as the risk of ALN involvement is high compared to other BC types.⁴⁷,⁴⁸ Complete axillary lymph node dissection may be indicated to assess the extent of disease and to achieve local control. Patients with inflammatory BC who undergo CALND experience improved locoregional control and overall survival rates compared to those who do not undergo adequate axillary surgery.¹⁴,¹⁵

STAGE IV BREAST CANCER

Some studies have shown that removing the primary breast tumor in stage IV BC may decrease the likelihood of developing new metastases leading to improved survival outcomes.⁴⁹–⁵¹ Tumor in LNs is a known source of systemic metastases so it might seem intuitive that resection of positive ALNs would also improve outcome.⁵²,⁵³ However, this has not been examined in randomized studies. Thus, there is no consensus on CALND, SLNB, or level I sampling in patients with stage IV BC with positive ALNs.

Palliative surgical resection of uncontrolled bulky axillary metastases may sometimes be necessary for patients when there is no immediate threat of dying from BC or other non-cancer visceral disease. This is particularly true if the tumor invades the overlying skin or where brachial plexus invasion causing severe pain is not palliated by radiation or other therapies. When performed, CALND is generally less considered for curative intent and more for pain alleviation and improving quality of life in patients with symptoms caused by LN involvement, especially with enlarged LNs unresponsive to systemic therapy.

DUCTAL CARCINOMA IN-SITU

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network suggests that SLNB should be considered in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) when there is an invasive component. Pure DCIS without an invasive component does not justify SLNB because of the low likelihood of LN metastasis (less than 1%).⁵⁴ When DCIS is treated by lumpectomy, it is reasonable to await the final pathological evaluation before deciding to do an SLNB because of the finding of previously unrecognized invasion in the excised lumpectomy specimen. The usual techniques used to do a SLNB can then be accurately performed as a second procedure when the breast has not been removed. In patients undergoing mastectomy for DCIS, a second procedure to find the SLN can only be performed for unexpected invasive disease if the node has a tracer in it to guide the surgeon. To avoid this issue, some surgeons perform a SLNB in all cases of DCIS undergoing mastectomy. However, iron oxide liquid Magtrace (Endomagnetics, Cambridge, UK) stays in the LN for weeks to months after subareolar lymphatic plexus injection during mastectomy. As such, the SLN can be removed later using a minor second operation if the final pathology reveals invasive characteristics.

Current Recommendations for Omission of Axillary Lymph Node Surgery

AVOIDING COMPLETE AXILLARY LYMPH NODE DISSECTION (see Figures 1, 2, 3)

The American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z0011 multicenter, randomized clinical trial was designed to evaluate the necessity of CALND in patients with early-stage BC who had positive SLNs. The trial included women undergoing breast-conserving surgery, radiation, and systemic therapy for clinical T1-T2 BC and 1 or 2 positive SLNs without extranodal extension. The trial found that patients with 1 or 2 positive SLNs who received CALND and those who did not had similar rates of overall survival and disease-free survival compared to those who had CALND.³⁶ There was no significant difference in axillary recurrences, which occurred at low rates in both groups (1%–2%).³⁶ The Z0011 trial supported the conclusion that patients with 1 or 2 positive SLNs who received adjuvant axillary radiation and systemic therapy could forego CALND without compromising oncological outcomes.

The multicenter, randomized controlled AMAROS trial evaluated the outcomes of patients with early-stage BC who had 1 or 2 positive SLNs and received adjuvant axillary radiation therapy compared to CALND. In addition, and unlike the Z0011 trial, the AMAROS trial included mastectomy patients. The AMAROS trial also concluded that it was safe to avoid CALND in selected patients with 1 or 2 positive SLNs who had received adjuvant axillary radiation therapy.³⁷ These findings support those of the Z0011 trial and further contribute to the growing body of evidence reinforcing the omission of CALND for specific patient populations.³⁷

In 2015, researchers from Northern Europe initiated the SENOMAC study that aimed to broaden the eligibility criteria to encompass significantly underrepresented groups in the previous studies, such as individuals undergoing mastectomy, patients with extracapsular extension in SLNs or T3 tumors, and male sex. The noninferiority study showed no difference in overall survival in patients who underwent SLNB without CALND but with adjuvant axillary radiation for clinically node-negative, pathologically node-positive primary T1 to T3 BC with 1 or 2 SLN macrometastases compared to patients who underwent CALND.³⁸

AVOIDING SENTINEL LYMPH NODE BIOPSY

In collaboration with the ‘Choosing Wisely’ initiative in 2016, the Society of Surgical Oncology recommended against the routine use of SLNB in clinically node-negative women aged 70 or older with early-stage hormone receptor-positive, HER2/ neu-negative invasive BC.¹⁰,³⁹ This guideline was supported by multiple investigations that demonstrated SLNB did not influence locoregional recurrence or BC-specific mortality in older women.

Martelli et al. examined the long-term safety of forgoing axillary surgery in patients over 70 years old with a negative clinical axilla (cN0) who had breast conserving surgery and adjuvant endocrine therapy.⁵⁵ The results indicated that axillary surgery did not improve overall survival or BC-specific survival over a 5-year period. The cumulative 15-year incidence of axillary disease was low, with rates of 5.8% for patients who underwent CALND compared to 3.7% for those who did not.⁵⁵ Similarly, Chung et al. assessed the safety of omitting SLNB in women over 70 with T1 to T2 tumors. They reported a 5-year overall survival of 70% and a BC specific survival of 96%.⁵⁶ The authors also noted that adjuvant systemic chemotherapy was less frequently offered, regardless of nodal status, suggesting that LN involvement did not significantly affect treatment decisions, as patients were more likely to die from causes other than BC.⁵⁶

The CALGB 9343 trial examined the necessity of adjuvant radiation after lumpectomy in older patients with early-stage hormone receptor-positive BC. Within this study, a small subset of patients did not undergo axillary surgery or radiation. Among this cohort, only 3% experienced ipsilateral axillary progression, compared to no progression in patients who received radiation without surgical axillary staging.⁵⁷ Given the low rate of axillary progression in those who avoided nodal surgery and radiotherapy, the authors suggested that SLNB could be safely omitted in this population.

If we could identify a subset of patients with low rates of LN metastases using standard pathologic characteristics, we might be able to justify omission of SLNB. The ideal patient in whom a SLNB could be avoided would be one in whom LN metastasis does not occur. Since no one has yet identified a population of BC patients with zero LN metastases, the next best hope would be to find BC patients with very low levels of LN metastases. Using our 28-year prospective SLNB database, we found less than 7% of patients irrespective of age with less than 1 cm, low-grade BCs showing no evidence of lymphovascular invasion had LN metastases.⁵⁸ This finding might justify a clinical study to determine the oncologic outcome of avoiding SLNB in BC patients with these tumor characteristics.

Patients with tubular carcinoma should also be considered for omission of SLNB. The 5-year disease-free survival rate is usually over 90%.⁵⁹ Further, it has been shown that less than 1 cm tubular carcinoma lesions have a less than 1% chance of LN metastasis.⁶⁰ Other pathological subtypes with a relatively low incidence of LN metastases include mucinous and medullary BC.⁶¹,⁶²

The SOUND trial aimed to determine if forgoing SLNB in patients with negative axillary US is noninferior in 5-year distant disease-free survival rates compared to performing SLNB. They found that patients over age 50 years with BCs less than 2 cm and with sonographically normal LNs undergoing breast conserving surgery and radiation therapy can safely avoid axillary surgery.²⁷

While there is emerging evidence regarding the omission of SLNB in patients with high-risk lesions and significant comorbidities, further research is needed to establish standardized protocols and guidelines. For patients with high-risk BCs, the approach to axillary staging with SLNB should be individualized where comorbidities may limit guideline-controlled treatment options. Patients with major comorbidities may not benefit from routine SLNB due to the potential risks of surgical complications outweighing the benefits. Further, if a patient is not a candidate for systemic chemotherapy, SLNB would not influence their treatment plan.

Figure 3. Management of clinically and/or radiologically positive ipsilateral axillary lymph nodes.⁸ Abbreviations: CALND, complete axillary lymph node dissection; cN+, clinically positive lymph nodes; FNA, fine needle aspiration; NAC, neoadjuvant chemotherapy; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy; US, ultrasound.

Molecular/Genetic Markers that Could Make Sentinel Node Biopsy Redundant

Apart from the special conditions for avoiding SLNB already described above, we can imagine the following 3 situations where surgical excision of ALNs would be redundant:

-

molecular or genetic tests done on BC tumor cells provide enough prognostic and predictive information that supersedes the information obtained from accurate pathologic documentation of metastases in the SLN;

-

BC tumor cells directly invade intra- or peri-tumoral blood vessels but not lymphatics; and

-

BC tumor cells do not directly invade lymphatics or blood vessels and therefore are not capable of metastasizing to either regional LNs or systemic sites.**

Molecular markers, such as hormone receptors, HER2/neu and Ki67, are routinely performed on BCs. When combined with demographic features (such as age at diagnosis) and pathologic characteristics (such as tumor size, grade, and the presence of lymphovascular invasion), the likelihood of LN and systemic metastases can be calculated and appropriate systemic treatment selected.⁶³While assessments of standard clinical and pathological features have been used to determine the use of adjuvant systemic therapy with early-stage BC, the challenge of accurately identifying those patients that will benefit from adjuvant therapies remains challenging. Gene expression assays can guide treatment for early-stage BC. The Oncotype DX test (Exact Sciences, Madison, WI), based upon the expression of 16 functional and 5 control genes, is usually done on the primary BC after lumpectomy or mastectomy in selected patients, where SLNB has already been performed.⁶⁴ The results are commonly used to advise adjuvant therapy. Several other commercially available genomic assays continue to be clinically validated.⁶⁵ These assays can be done on needle biopsy specimens prior to surgical treatment and such a practice, if it were to become routine, might be as valuable as SLNB.Even in the age of molecular medicine, the presence or absence of BC in regional LNs remains the strongest predictor of systemic metastases.⁶⁶ LNs thus act as a highly efficient bioassay for identifying metastasis-competent cells. If we knew that BC tumor cells were able to invade directly into intra- or peri-tumoral blood vessels and metastasize to systemic sites, and bypass LNs, we could avoid SLNB. Molecular evidence of distinct parental subclones of cells that bypass regional LNs has been shown in both breast and colorectal cancer.⁶⁷,⁶⁸ Similarly, it is conceivable that we could identify by molecular means tumors where neither lymphatic nor blood vessel invasion is likely. Unfortunately, such assays are not yet available.

Other advances that allowed de-escalation of axillary nodal surgeryDe-escalation of axillary node surgery did not occur in a vacuum. At the beginning of the modern age, BC was managed predominantly by surgeons. Successful management of BC, including the avoidance of axillary node surgery, developed because of the multidisciplinary approach to the disease in its many manifestations. Each stage of diminished axillary node surgery has been supported by countless revolutionary changes in many disciplines that interact directly or indirectly in the management of BC (Figure 4). Each discipline played a necessary role in how we can now confidently select to omit excision of ALNs.

We anticipate a further decrease in axillary node surgery with developing technologies in axillary imaging and by incorporating clinicopathological and molecular/genetic predictors of LN metastases. Innovative imaging techniques, such as US, MRI, and molecular imaging, may offer a more precise, personalized approach to BC management.⁵⁸,⁶⁹ However, challenges persist, including the need for standardized imaging protocols, consistent interpretation, and large-scale clinical validation of emerging methods. As BC management continues to evolve, multidisciplinary clinical and translational research collaboration is essential to balance accurate

Figure 4. Advances that contributed to development of safe, selective omission of axillary lymph node surgery in breast cancer

-

Research and development

○ Government, pharmaceutical, university, and private funded research programs

-

Biological understanding

○ Improved awareness of the biology and progression of BC⁷⁰

○ Increased understanding of patterns and sites of metastasis⁶⁹

-

Imaging and diagnostics

○ Advances in the imaging of the breast, LNs and systemic sites¹⁶–²¹

○ Needle biopsy of primary and metastatic BCs³³–³⁵

-

Therapeutic advances

○ Discoveries of new chemotherapeutic drugs, targeted therapies, endocrine therapy, and immunotherapy⁴

○ Development of successful adjuvant therapies⁷¹

○ Radiation technologies and research⁷²

-

Sub-specialization in oncology

○ Subspecialization of BC oncologists

○ Superspecialized breast surgeons⁷

-

Pathology and molecular subtyping

○ BC pathological subtypes reclassification⁷³

○ BC molecular subtypes recognized⁷⁴

○ Molecular/genetic aids for selection of adjuvant therapy⁴⁴

-

Patient empowerment and awareness

○ Breast cancer awareness

○ Women taking charge – change at political and cultural level

○ Increasing awareness propagated through schools, churches, and social gatherings

-

Clinical decision support

○ National and international guidelines⁸

○ Advances in mathematical outcome prediction models⁷⁵

○ High-risk and genetic counselors⁷⁶

○ Tumor boards⁷⁷

Conclusion

The evaluation of ALNs in BC patients continues to evolve. De-escalation of ALN surgery has historically been the clinical pattern starting from the Halstedian dogma of levels I, II, and III LN dissection in all BC patients, regardless of whether LNs were clinically suspicious or not. The carefully controlled era of SLNB is still the standard of care in most cases. The morbidity of nodal surgery while markedly decreased with SLNB has not completely disappeared. Recently, the trend has turned to selective complete avoidance of all axillary nodal surgery. During these historic times the accompanying belief in the therapeutic value of CALND has largely evaporated, justifying removal of LNs for staging and treatment planning purposes in some cases. As the genetic/molecular era leads us to better predictive and prognostic tests, we anticipate a time when axillary nodal surgery may disappear completely.Conflicts of Interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgement:

This review was supported by the Nathanson/Rands Chair in Breast Cancer Research, Detroit, Michigan, and by the Team Angels, Sterling Heights, Michigan.

References

1. Fisher B, Montague E, Redmond C, et al. Comparison of radical mastectomy with alternative treatments for primary breast cancer:A first report of results from a prospective randomized clinical trial. Cancer. 1977;39(6):2827-2839. doi:10.1002/1 097-0142(197706)39:6<2827::AID-CNCR2820390 671>3.0.CO;2-I

2. Fisher B, Dignam J, Bryant J, Wolmark N. Five versus more than five years of tamoxifen for lymph node-negative breast cancer: updated findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-14 randomized trial. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(9):684-690. doi:10.1093/jnci/ 93.9.684

3. Fisher B, Dignam J, Mamounas EP, et al. Sequential methotrexate and fluorouracil for the treatment of node-negative breast cancer patients with estrogen receptor-negative tumors: eight-year results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) B-13 and first report of findings from NSABP B-19 comparing methotrexate and fluorouracil with conventional cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil. J Clin Oncol. 1996; 14(7):1982-1992. doi:10.1200/JCO.1996.14.7.1982

4. Romond EH, Perez EA, Bryant J, et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(16):1673-1684. doi:10.1056/NEJM oa052122

5. Shah C, Al-Hilli Z, Vicini F. Advances in Breast Cancer Radiotherapy: Implications for Current and Future Practice. JCO Oncol Pract. 2021;17(12): 697-706. doi:10.1200/OP.21.00635

6. Corti C, Batra-Sharma H, Kelsten M, Shatsky RA, Garrido-Castro AC, Gradishar WJ. Systemic Therapy in Breast Cancer. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2024;44(3):e432442. doi:10.1200/EDBK_432442

7. American Society of Breast Surgeons. Consensus statement on axillary management for patients with in-situ and invasive breast cancer: a concise overview. 2022. Accessed September 24, 2024. https://www.breastsurgeons.org/docs/statements/management-of-the-axilla.pdf

8. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Breast cancer, version 4.2024. Published online July 3, 2024. Accessed September 24, 2024. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf

9. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Breast Cancer. Accessed September 24, 2024. https://society.asco.org/practice-patients/guidelines/breast-cancer

10. Society of Surgical Oncology. Breast Cancer. Accessed September 24, 2024.

https://surgonc.org/resources/guidelines/

11. Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, et al. Sentinel-lymph-node resection compared with conventional axillary-lymph-node dissection in clinically node-negative patients with breast cancer: overall survival findings from the NSABP B-32 randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11 (10):927-933. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70207-2

12. Veronesi U, Viale G, Paganelli G, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer: ten-year results of a randomized controlled study. Ann Surg. 2010;251(4):595-600. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b01 3e3181c0e92a

13. Boughey JC. Sentinel lymph node surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with node-positive breast cancer: the ACOSOG Z1071 (Alliance) clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(14):1455. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.278932

14. Fayanju OM, Ren Y, Greenup RA, et al. Extent of axillary surgery in inflammatory breast cancer: a survival analysis of 3500 patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;180(1):207-217. doi:10.1007/s105 49-020-05529-1

15. Rehman S, Reddy CA, Tendulkar RD. Modern outcomes of inflammatory breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2012;84(3):619-624. doi:10.1016/j.ijr obp.2012.01.030

16. Britton P, Moyle P, Benson JR, et al. Ultrasound of the axilla: where to look for the sentinel lymph node. Clin Radiol. 2010;65(5):373-376. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2010.01.013

17. Swinson C, Ravichandran D, Nayagam M, Allen S. Ultrasound and fine needle aspiration cytology of the axilla in the pre-operative identification of axillary nodal involvement in breast cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol EJSO. 2009;35(11):1152-1157. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2009.03.008

18. Ha SM, Chae EY, Cha JH, Shin HJ, Choi WJ, Kim HH. Diagnostic performance of standard breast MR imaging compared to dedicated axillary MR imaging in the evaluation of axillary lymph node. BMC Med Imaging. 2020;20(1):45. doi:10.1186/s 12880-020-00449-4

19. Kuijs VJL, Moossdorff M, Schipper RJ, et al. The role of MRI in axillary lymph node imaging in breast cancer patients: a systematic review. Insights Imaging. 2015;6(2):203-215. doi:10.1007/s13244-015-0404-2

20. De Mooij CM, Sunen I, Mitea C, et al. Diagnostic performance of PET/computed tomography versus PET/MRI and diffusion-weighted imaging in the N- and M-staging of breast cancer patients. Nucl Med Commun. 2020;41(10):995-1004. doi:10.1097/MNM.0000000000001254

21. Riegger C, Koeninger A, Hartung V, et al. Comparison of the diagnostic value of FDG-PET/CT and axillary ultrasound for the detection of lymph node metastases in breast cancer patients. Acta Radiol. 2012;53(10):1092-1098. doi:10.125 8/ar.2012.110635

22. Zheng H, Zhao R, Wang W, et al. The accuracy of ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration and core needle biopsy in diagnosing axillary lymph nodes in women with breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 2023;13:11 66035. doi:10.3389/fonc.2023.1166035

23. Huang Y, Liu Y, Wang Y, et al. Quantitative analysis of shear wave elastic heterogeneity for prediction of lymphovascular invasion in breast cancer. Br J Radiol. 2021;94(1127):20210682. doi:10.1259/bjr.20210682

24. Schwartz T. At the speed of SOUND: the pace of change for axillary management in breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2024;31(5):2801-2803. doi:10.1245/s10434-024-15010-8

25. Zhang H, Sui X, Zhou S, Hu L, Huang X. Correlation of conventional ultrasound characteristics of breast tumors With axillary lymph node metastasis and Ki‐67 expression in patients with breast cancer. J Ultrasound Med. 2019;38(7):1833-1840. doi:10.1002/jum.14879

26. Kim WH, Kim HJ, Lee SM, et al. Preoperative axillary nodal staging with ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging: predictive values of quantitative and semantic features. Br J Radiol. 2018;91(1092):2 0180507. doi:10.1259/bjr.20180507

27. Gentilini OD, Botteri E, Sangalli C, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy vs no axillary surgery in patients with small breast cancer and negative results on ultrasonography of axillary lymph nodes: the SOUND randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9(11):1557. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2023.3759

28. Guo Q, Dong Z, Zhang L, et al. Ultrasound features of breast cancer for predicting axillary lymph node metastasis. J Ultrasound Med. 2018; 37(6):1354-1353. doi:10.1002/jum.14469

29. Li XL, Xu HX, Li DD, et al. A risk model based on ultrasound, ultrasound elastography, and histologic parameters for predicting axillary lymph node metastasis in breast invasive ductal carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):3029. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-03582-3

30. Yun SJ, Sohn YM, Seo M. Risk stratification for axillary lymph node metastases in breast cancer patients: what clinicopathological and radiological factors of primary breast cancer can predict preoperatively axillary lymph node metastases? Ultrasound Q. 2017;33(1):15-22. doi:10.1097/RU Q.0000000000000249

31. Tran HT, Pack D, Mylander C, et al. Ultrasound -based nomogram Identifies breast cancer patients unlikely to harbor axillary metastasis: towards selective omission of sentinel lymph node biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27(8):2679-2686.

doi:10.1245/s10434-019-08164-3

32. Zhang M, Zha H, Pan J, et al. Development of an ultrasound-based nomogram for predicting pathologic complete response and axillary response in node-positive patients with triple- negative breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2024;24(6):e48 5-e494.e1. doi:10.1016/j.clbc.2024.03.012

33. Lee J, Park HY, Kim WW, Park CS, Jeong M, Jung JH. Efficacy of ultrasound-guiided core needle biopsy in detecting metastatic axillary lymph nodes in breast cancer. J Surg Ultrasound. 2020;7(2):21-28. doi:10.46268/jsu.2020.7.2.21

34. Luo Y, Zhao C, Gao Y, et al. Predicting axillary lymph node status With a nomogram based on breast lesion ultrasound features: performance in N1 breast cancer patients. Front Oncol. 2020; 10:581321. doi:10.3389/fonc.2020.581321

35.Nathanson SD, Burke M, Slater R, Kapke A. Preoperative Identification of the Sentinel Lymph Node in Breast Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007; 14(11):3102-3110. doi:10.1245/s10434-007-9494-5

36. Giuliano AE, Ballman KV, McCall L, et al. Effect of axillary dissection vs no axillary dissection on 10-year overall survival among women with invasive breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis: the ACOSOG Z0011 (Alliance) randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(10):918. doi:10.1001/jama.201 7.11470

37. Donker M, Van Tienhoven G, Straver ME, et al. Radiotherapy or surgery of the axilla after a positive sentinel node in breast cancer (EORTC 10981-22023 AMAROS): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(12):1303-1310. doi:10.1016/S1470 -2045(14)70460-7

38. De Boniface J, Filtenborg Tvedskov T, Rydén L, et al. Omitting axillary dissection in breast cancer with sentinel-node metastases. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(13):1163-1175. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa23 13487

39. The American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. Choosing Wisely® Campaign. Accessed September 24, 2024. https://choosingwisely.org/

40. Kuehn T, Bauerfeind I, Fehm T, et al. Sentinel-lymph-node biopsy in patients with breast cancer before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (SENTINA): a prospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(7):609-618. doi:10.1016/S1 470-2045(13)70166-9

41. Caudle AS, Yang WT, Krishnamurthy S, et al. Improved Axillary Evaluation Following Neoadjuvant Therapy for Patients With Node-Positive Breast Cancer Using Selective Evaluation of Clipped Nodes: Implementation of Targeted Axillary Dissection. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(10):1072-1078. doi:10.1200/J CO.2015.64.0094

42. Nathanson D. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer: past, present, and future. J Oncol Res Ther. 2023;8(3). doi:10.29011/2574-710X.10178

43. Caudle AS, Yang WT, Mittendorf EA, et al. Selective Surgical Localization of Axillary Lymph Nodes Containing Metastases in Patients With Breast Cancer: A Prospective Feasibility Trial. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(2):137. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.201 4.1086

44. Plecha D, Bai S, Patterson H, Thompson C, Shenk R. Improving the accuracy of axillary lymph node surgery in breast cancer with ultrasound-guided wire localization of biopsy proven metastatic lymph nodes. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(13):4241-4246. doi:10.1245/s10434-015-4527-y

45. Hartmann S, Reimer T, Gerber B, Stubert J, Stengel B, Stachs A. Wire localization of clip-marked axillary lymph nodes in breast cancer patients treated with primary systemic therapy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44(9):1307-1311. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2 018.05.035

46. Balasubramanian R, Morgan C, Shaari E, et al. Wire guided localisation for targeted axillary node dissection is accurate in axillary staging in node positive breast cancer following neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020;46(6):1028-1033. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2019.12.007

47. Anderson WF, Chu KC, Chang S. Inflammatory breast carcinoma and noninflammatory locally advanced breast carcinoma: distinct clinicopathologic entities? J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(12):2254-2259. doi:10.1200/JCO.2003.07.082

48. Yang WT, Le-Petross HT, Macapinlac H, et al. Inflammatory breast cancer: PET/CT, MRI, mammography, and sonography findings. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;109(3):417-426. doi:10.100 7/s10549-007-9671-z

49. Fields RC, Jeffe DB, Trinkaus K, et al. Surgical resection of the primary tumor is associated with increased long-term survival in patients with stage IV breast cancer after controlling for site of metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(12):3345-3351. doi:10.1245/s10434-007-9527-0

50. Gnerlich J, Jeffe DB, Deshpande AD, Beers C, Zander C, Margenthaler JA. Surgical removal of the primary tumor increases overall survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer: analysis of the 1988–2003 SEER data. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007; 14(8):2187-2194. doi:10.1245/s10434-007-9438-0

51. Rao R, Feng L, Kuerer HM, et al. Timing of surgical intervention for the intact primary in stage IV breast cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008; 15(6):1696-1702. doi:10.1245/s10434-008-9830-4

52. Brown M, Assen FP, Leithner A, et al. Lymph node blood vessels provide exit routes for metastatic tumor cell dissemination in mice. Science. 2018;359(6382):1408-1411. doi:10.1126/science.a al3662

53. Pereira ER, Kedrin D, Seano G, et al. Lymph node metastases can invade local blood vessels, exit the node, and colonize distant organs in mice. Science. 2018;359(6382):1403-1407. doi:10.112 6/science.aal3622

54. Tada K, Ogiya A, Kimura K, et al. Ductal carcinoma in situ and sentinel lymph node metastasis in breast cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2010;8(1):6. doi:10.1186/1477-7819-8-6

55. Martelli G, Miceli R, Daidone MG, et al. Axillary dissection versus no axillary dissection in elderly patients with breast cancer and no palpable axillary nodes: results after 15 Years of follow-Up. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(1):125-133. doi:10.1245/s10434-010-1217-7

56. Chung AP, Dang CM, Karlan SR, et al. A prospective study of sentinel node biopsy omission in women age ≥ 65 years with ER+ breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2024;31(5):3160-3167. doi:10.124 5/s10434-024-15000-w

57. Hughes KS, Schnaper LA, Berry D, et al. Lumpectomy plus tamoxifen with or without Irradiation in women 70 years of age or older with early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(10): 971-977. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa040587

58. Nathanson S, Leonard-Murali S, Bui J, et al. Combined selected pathological variables predict a low likelihood of axillary node metastasis in breast cancer patients regardless of age. Poster presented at: American Society of Breast Surgeons 25th Annual Meeting; April 10, 2024; Orlando, FL.

59. Min Y, Bae SY, Lee HC, et al. Tubular carcinoma of the breast: clinicopathologic features and survival outcome compared with ductal Carcinoma in situ. J Breast Cancer. 2013;16(4):404. doi:10.4048/jbc.2013.16.4.404

60. Javid SH, Smith BL, Mayer E, et al. Tubular carcinoma of the breast: results of a large contemporary series. Am J Surg. 2009;197(5):674-677. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.05.005

61. Budzik M, Sobieraj M, Sobol M, et al. Medullary breast cancer is a predominantly triple-negative breast cancer – histopathological analysis and comparison with invasive ductal breast cancer. Arch Med Sci. 2019;18(2):432-439. doi:10.5114/a oms.2019.86763

62. Marrazzo E, Frusone F, Milana F, et al. Mucinous breast cancer: A narrative review of the literature and a retrospective tertiary single-centre analysis. The Breast. 2020;49:87-92. doi:10.1016/j. breast.2019.11.002

63. Bhargava R, Esposito NN, OʹConnor SM, et al. Magee EquationsTM and response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in ER+/HER2-negative breast cancer: a multi-institutional study. Mod Pathol. 2021;34(1):77-84. doi:10.1038/s41379-020-0620-2

64. Paik S, Shak S, Tang G, et al. A Multigene Assay to Predict Recurrence of Tamoxifen-Treated, Node-Negative Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004; 351(27):2817-2826. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa041588

65. Pauls M, Chia S. Clinical Utility of Genomic Assay in Node-Positive Early-Stage Breast Cancer. Curr Oncol. 2022;29(7):5139-5149. doi:10.3390/cu rroncol29070407

66. Jana S, Muscarella RA, Jones D. The Multifaceted Effects of Breast Cancer on Tumor-Draining Lymph Nodes. Am J Pathol. 2021;191 (8):1353-1363. doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2021.05.006

67. Nathanson SD, Detmar M, Padera TP, et al. Mechanisms of breast cancer metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2022;39(1):117-137. doi:10.1007/s105 85-021-10090-2

68. Naxerova K, Reiter JG, Brachtel E, et al. Origins of lymphatic and distant metastases in human colorectal cancer. Science. 2017;357(6346):55-60. doi:10.1126/science.aai8515

69. Nathanson SD, Dieterich LC, Zhang XHF, et al. Associations amongst genes, molecules, cells, and organs in breast cancer metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2023;41:417-437. doi:10.1007/s10585-023-10230-w

70. Rakha EA, Tse GM, Quinn CM. An update on the pathological classification of breast cancer. Histopathology. 2023;82(1):5-16. doi:10.1111/his14786

71. Bonadonna G, Rossi A, Valagussa P, Banfi A, Veronesi U. The CMF program for operable breast cancer with positive axillary nodes:Updated analysis on the disease-free interval, site of relapse and drug tolerance. Cancer. 1977;39(6):2904-2915. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(197706)39:6<2904::AID-CNCR2820390677>3.0.CO;2-8

72. Kaidar-Person O, Meattini I, Poortmans P, eds. Breast Cancer Radiation Therapy: A Practical Guide for Technical Applications. 1st ed. Springer International Publishing; 2022.

73. Hoda SAF, Koerner FC, Brogi E, Rosen PP. Rosen’s Breast Pathology. 5th edition. Wolters Kluwer; 2021.

74. Perou CM, Sørlie T, Eisen MB, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000; 406(6797):747-752. doi:10.1038/35021093

75. Van Zee KJ, Manasseh DME, Bevilacqua JLB, et al. A Nomogram for Predicting the Likelihood of Additional Nodal Metastases in Breast Cancer Patients With a Positive Sentinel Node Biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10(10):1140-1151. doi:10.124 5/ASO.2003.03.015

76. Narod SA, Foulkes WD. BRCA1 and BRCA2: 1994 and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(9):665-676. doi:10.1038/nrc1431

77. Coles CE, Earl H, Anderson BO, et al. The Lancet Breast Cancer Commission. The Lancet. 2024;403(10439):1895-1950. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00747-5