Professional CGM for Managing Hypoglycemia in Older Adults

Professional Continuous Glucose Monitoring for Diabetes Management in Older Adults with Type 2 Diabetes on Insulin: An Underutilized Tool?

Elena Toschi, MD¹²³, Christine Slyne, BA¹, Amy Michals, MPH¹, Noa Krakoff, BS¹, Medha Munshi, MD¹²³

- Joslin Diabetes Center

- Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

- Harvard Medical School

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 October 2025

CITATION: Toschi, E., Slyne, C., et al., 2025. Professional Continuous Glucose Monitoring for Diabetes Management in Older Adults with Type 2 Diabetes on Insulin: An Underutilized Tool? Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(10).

https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i10.6913

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i10.6913

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

Background: Professional CGM (continuous glucose monitoring) holds the potential to improve diabetes management in older adults with insulin-treated type 2 diabetes. However, information on professional CGM use and the reasons for and barriers to prescribing it in clinical practice are limited.

Methods: At a tertiary diabetes-only clinic, we reviewed electronic medical records of older adults with type 2 diabetes (≥65 years) on insulin that underwent professional CGM. Additionally, we surveyed clinicians on the reasons for and barriers to prescribing proCGM.

Results: During a 3-year period, a total of 2,481 older adults with type 2 diabetes (72±7 years, HbA1c 8.2±1.5% and diabetes duration 21±10 years) using insulin were seen in the clinic. One-hundred and sixty-nine older adults (7% of the total) underwent professional CGM. In the 139 older adults (77±8 years, HbA1c 8.0±1.5%, duration of diabetes 21±12 years) with viable proCGM data, the mean duration of hypoglycemia was high (<70 mg/dL: 5.5±6.3%; ≤54 mg/dL: 2.2±3.5%) and 86% of the cohort had ≥1 episodes of hypoglycemia (≥15 min). A clinically significant discrepancy (≥0.5%) between HbA1c and glucose management indicator was observed in 65% of the cohort. More than 80% (20/25) of the clinicians reported the use of professional CGM was helpful for pattern management and identification of hypoglycemia, however more than half of clinicians reported difficulty with clinical workflow and insurance coverage.

Conclusion: In older adults with type 2 diabetes on insulin, professional CGM identified a high burden of hypoglycemia, despite suboptimal HbA1c. The great majority of clinicians reported use of professional CGM helpful for diabetes management, however infrastructures issues were a major barrier to using it.

Keywords:

- Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM)

- Glucose Management Indicator (GMI)

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Older Adults

- Hypoglycemia

- Insulin

Introduction

In the United States, several millions of older adults (≥65 years) have type 2 diabetes (T2D) treated with basal or basal bolus insulin. Older adults with T2D treated with insulin are at high risk of hypoglycemia and its related poor clinical outcomes. Risk of hypoglycemia may not correlate with glucose average and HbA1c level, therefore hypoglycemia may be difficult to recognize, especially in the older population where hypoglycemia unawareness may be present. In randomized controlled studies, in older adults with diabetes on insulin, the use of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) has shown to improve glycemic control and mitigate the risk of hypoglycemia. In older adults with type 1 diabetes, the use of CGM derived metrics, such as glucose variability and glucose management indicator (GMI), can better identify individuals at higher risk of hypoglycemia compared to HbA1c alone. However, currently there are very limited data on CGM metrics and their relationship with HbA1c, glycemic control and risk of hypoglycemia in older adults with T2D.

In addition, the use of personal CGM in the adult population has shown a reduction in the risk of emergency department visits and hospitalization related to hypoglycemia. However, the uptake of personal CGM in older adults with T2D on insulin is limited. Older adults may experience cognitive and functional impairments that can interfere with the ability to initiate and use new technologies, and these impairments may be a barrier to initiating personal CGM. In addition, a report of a workshop of older adults and their caregivers focusing on the initiation and use of CGM suggested that older adults may need more technical support and a dynamic age-specific education that may not be yet in place in clinics. Lastly, despite broad coverage of personal CGM in insulin-treated older adults, its uptake is still <10%, possibly due to racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities.

Professional CGM (proCGM) is a viable option for older adults with T2D that are unable or unwilling to use a personal CGM. ProCGM devices, which require no input from patients and provide no data to them in real time, are provided by the clinicians and worn by the person with diabetes for a short period – up to two weeks – providing insight on glycemic pattern. The American Diabetes Association Grade E (expert opinion) recommends the use of proCGM “in identifying and correcting patterns of hyper- and hypoglycemia in people with type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes.” However, proCGM is not used commonly in clinical practice. The reasons for the underutilization of this tool are not clear.

In this retrospective cross-sectional study, we reviewed electronic medical records of older adults (≥65 years) with T2D on insulin seen in a tertiary diabetes-only clinic between January 2017 and March 2020, and analyzed data from proCGM performed during this time in the same cohort of patients. Furthermore, we surveyed clinicians in the clinic to understand the reasons for and barriers to prescribing proCGM in clinical practice.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cross-sectional analysis on older adults (≥65 years) with T2D seen in the clinic between January 1, 2017 and March 1, 2020 and identified older adults that underwent proCGM. Demographic and clinical data were retrieved from the clinical medical records. The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board.

Professional CGM: Data from proCGM prescribed to older adults (age ≥65 years) with T2D on insulin (basal or basal/bolus) were collected. Patients labelled with ICD code consistent with prediabetes, hypoglycemia without associated diabetes ICD code, pancreatic diabetes, or impaired glucose tolerance were excluded, along with patients with T2D not on insulin. Data collected with the proCGM were “masked,” therefore the patient had no interaction with the sensor and no access to real-time glucose data. At the visit (end of the wear period), the sensor was scanned and CGM data were uploaded to the software to generate a standard Ambulatory Glucose Profile report, which includes CGM-measured mean glucose concentration during the period of the CGM wear. Data were run through Spyder 3.1 IDE to retrieve CGM metrics for time in range (TIR) defined as glucose 70-180 mg/dL. Time in hypoglycemia defined as <70 mg/dL and ≤54 mg/dL, and time above range was defined as glucose 180-250 mg/dL and >250 mg/dL. Data on proCGM was deemed sufficient for analysis if there was ≥10 days of data available from the 14 days of wear. Coefficient of variation (CV%) was calculated as: (standard deviation / mean glucose in mg/dL) × 100. GMI was calculated as: 3.31 + (0.02392 × mean glucose in mg/dL).

Laboratory HbA1c values collected within one month of proCGM wear were used.

Clinician Survey: We administered an anonymous survey using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Joslin Diabetes Center to clinicians (endocrinologist and nurse practitioners) seeing patients at our institution, a diabetes-only center (Joslin Diabetes Center), to assess reasons for and barriers to prescribing proCGM between March and June 2023.

Statistical analysis: For categorical variables, data are reported as number (n) and percentage (%) of the cohort. Data are reported as mean ± SD for data with normal distribution and as median and first and third interquartile (quartile 1, quartile 3) for data with non-normal distribution. SAS version 9.4 software was used for all analyses and included Pearson correlations, Student t tests, Fisher exact tests, and simple linear regression modeling. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 2,481 older adults (≥65 years) with T2D using insulin (age 72±7 years, HbA1c 8.2±1.5%, diabetes duration 21±10 years) were seen at the Joslin Diabetes Center between January 2017 and March 2020. One-hundred and sixty-nine older adults with T2D on insulin (7% of the entire cohort) underwent proCGM and 139 (82%) had sufficient proCGM data to analyze. Patients undergoing proCGM were older compared to the whole cohort (age: 77±8 vs. 72±7 years; p<0.001), and had similar glycemic control as HbA1c (8.0±1.5 vs 8.2±1.5%; p=ns), as well as duration of diabetes (21±12 vs 21±10 years; p=ns).

| All | Pro-CGM | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 2,481 | 139 | |

| Age (years) | 72 ± 7 | 77 ± 8 | <0.001 |

| Duration of diabetes (years) | 21±10 | 21±12 | NS |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.2±1.5 | 8.0±1.5 | NS |

| GMI (%) | NA | 7.3±1.4 | – |

| CV (%) | NA | 42% | – |

| Duration of Hypoglycemia <70 mg/dL (min/day) | NA | 80±92 | – |

| Duration of Hypoglycemia <54 mg/dL (min/day) | NA | 32±51 | – |

| Duration of Nocturnal Hypoglycemia <70 mg/dL (min/day) | NA | 24 (6, 60) | – |

| Episodes of Hypoglycemia (>20 consecutive min/day) (episodes/day) | NA | 86% | – |

| % of cohort with CV ≥36% | NA | 58 (49) | – |

In the cohort of 139 older adults with viable CGM data, the mean duration of hypoglycemia (<70 mg/dL) was 80±92 min/day (5.5±6.3%) and clinically significant hypoglycemia (≤54 mg/dL) was 32±51 min/day (2.2±3.5%). A total of 86% of the cohort (n=119) had ≥1 episode of hypoglycemia (≥15 consecutive minutes of glucose level <70 mg/dL). The comparison between older adults with T2D with (n=119) and without (n=20) hypoglycemia did not show a statistically significant difference in age (77±6 vs 76±8 years, p=ns), duration of diabetes (21±12 vs 20±12 years, p=ns) or HbA1c (7.9±1.4 vs 8.3±2.0, p=ns), while a greater number of older adults with hypoglycemia had a CV >36% compared to the ones without hypoglycemia (49% vs 1%, p=0.0003).

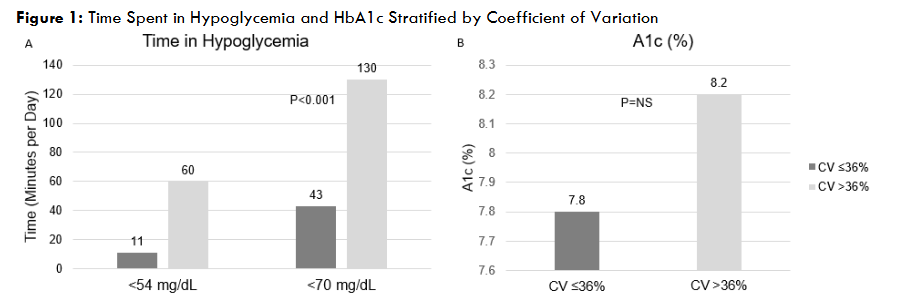

When we analyzed data for the whole cohort by CV (<36 and ≥36%), glycemic control measured by HbA1c was not different (7.8 vs 8.2%, p=ns), however, time spent in hypoglycemia, both <70 mg/dL and <54 mg/dL was higher in the cohort with CV≥36% compared to <36% [(120 vs 43 min/day mg/dL; p <0.0001) and (60 vs 11 min/day; p <0.0001)].

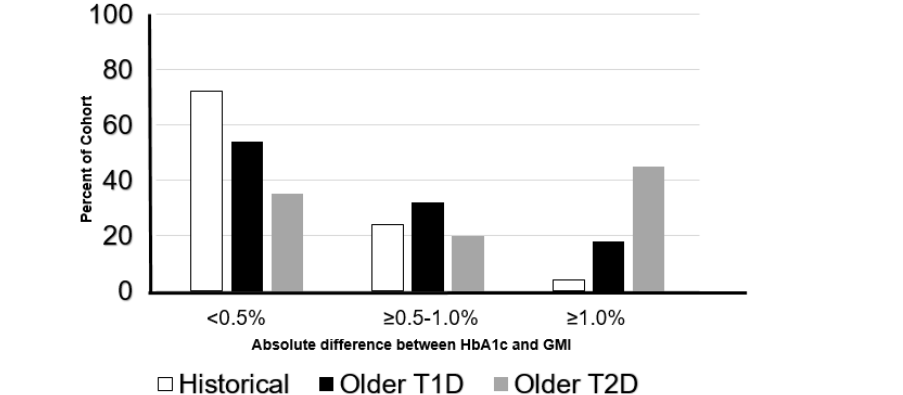

Next, we looked at the relationship between glycemic control, measured by laboratory HbA1c, and GMI. We observed an absolute clinically significant difference between HbA1c and GMI greater than 0.5% in 65% of the cohort and a difference between HbA1c and GMI greater than 1% in 45% of the cohort.

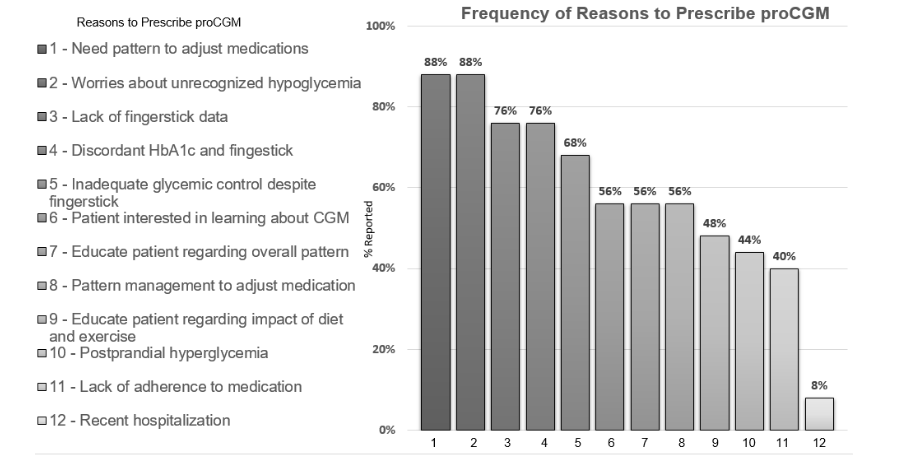

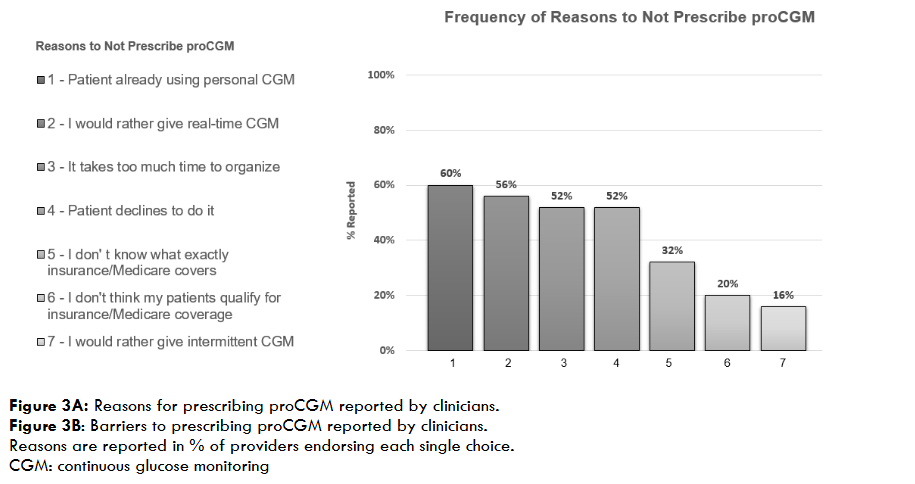

To assess the reasons for and barriers to prescribing proCGM, we surveyed twenty-five clinicians (60% endocrinologist and 40% nurse practitioners). They reported that the most common reasons to prescribe proCGM were: pattern management to adjust medications (88%), followed by worries of unrecognized hypoglycemia (88%), and lack of glucose data (76%) and discordant HbA1c and fingersticks (76%). Other than the patient already using personal CGM and/or eligible to use personal CGM (62%), clinicians reported the barriers to prescribing proCGM were: the time to organize proCGM in the clinic (52%), patient unwillingness to undergo proCGM (52%) and uncertainty whether proCGM was covered by patient’s insurance plan (32%) or if patients qualified for insurance coverage for proCGM wear (20%).

Figure 3: Reasons for and Barriers to Prescribing proCGM Reported by Clinicians

Discussion

In a large cohort of older adults with T2D on insulin seen in a tertiary diabetes-only clinic, the use of proCGM showed a high percentage of time spent in hypoglycemia independent of HbA1c, and a clinically relevant discrepancy between HbA1c and GMI. In addition, clinicians surveyed on the use of proCGM in clinic reported that proCGM provided useful data for pattern management and identification of unrecognized hypoglycemia, however, infrastructure issues, such as clinical workflow and patient cost, were among major barriers to prescribing it.

The finding of high percentage of hypoglycemia detected by CGM, independent of HbA1c value is consistent with the data in literature, where the limitation of HbA1c value to detect hypoglycemia has been described. Additionally, in our cohort, glycemic variability was a better predictor of risk of hypoglycemia, independent of HbA1c, which is consistent with data in the literature in older persons with T1D. The incidence of episodes of hypoglycemia (episode of glucose <70 mg/dL for ≥15 consecutive minutes) was high in this cohort of the older adults with T2D on insulin. Episodes of hypoglycemia in the older population have been associated with poor clinical outcomes such as falls, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations. These findings highlight how proCGM is a valuable clinical tool to identify hypoglycemia in older adults with T2D who find using personal CGM challenging. Clinicians should consider periodic use of proCGM to uncover unrecognized hypoglycemia, optimize diabetes medications, and individualize glycemic goals to improve outcomes.

Next, we described that the discrepancy between HbA1c and GMI in this cohort of older adults with T2D. This discrepancy was even more frequent than what has been previously described in adults with T1D or T2D and older adults with T1D.

Overall, these findings highlight the usefulness of proCGM to assess glycemic control and identify hypoglycemia, irrespective of HbA1c value. The data provided by proCGM on glycemic pattern and hypoglycemia can be especially relevant in older adults who are unable or unwilling to initiate the use of personal CGM and/or able to afford the ongoing cost of personal CGM. Clinicians can use such information to guide therapeutic decisions and develop a personalized diabetes management plan with minimal burden on the patient.

Previously, in a small study in the primary care setting, the use of pro-CGM was associated with improvement in diabetes management. The survey administered to clinicians working in our tertiary diabetes-only clinic confirmed the seen benefit of performing proCGM for pattern management, recognition of hypoglycemia and to guide therapeutic decisions. However, they reported several reasons for not prescribing proCGM, among which were clinical process, uncertainty of insurance coverage, and cost. These findings highlight the complexity of implementing the use of a novel tool into the clinical workflow, and concerns with insurance reimbursement to cover proCGM. Clinics should consider developing protocols for workflows, and staff training for the use of proCGM to help identify patients at high risk for hypoglycemia, and for CGM pattern interpretation. Insurers should consider expanding coverage policies to support the use of proCGM in older populations to help identify hypoglycemia and reduce the risk of its consequences such as falls, ED visits and hospitalizations.

The limitations of our study include the retrospective nature and its single-center, observational design. Our study lacks information on the individual reason clinicians prescribed proCGM and, as well as prospective information on impact of proCGM data on clinical care. Additionally, the CGM system used may not be the most accurate in detecting hypoglycemia, and CGM data are from one-time-only wear, and may not reflect long-term glycemic control.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the use of proCGM in older adults with T2D on insulin identified a high percentage of time spent in hypoglycemia, independent of HbA1c, and a discrepancy between HbA1c and GMI. Infrastructure issues, such as clinical workflow and insurance coverage, and patient-related cost are a major barrier reported by clinicians to implement the use of proCGM in clinical practice. Clinics should establish workflows for periodic use of proCGM, while insurers should consider expansion of coverage to improve overall outcomes in this older frail populations.

Acknowledgments

Funding and Duality of Interest

Elena Toschi receives funding from The Beatson Foundation and The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust and is a consultant for Vertex and Sequel. Medha Munshi receives funding from Dexcom, Inc and NIH DP3 Grant (1DP3DK112214-01) and is a consultant for Sanofi and Medtronic. Christine Slyne, Amy Michals, and Noa Krakoff have no duality of interest.

Author Contributions

E.T., C.S., and M.M. contributed to study design and concept. E.T., C.S., A.M., N.K., and M.M. contributed to data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation. E.T., and C.S. drafted the manuscript, and E.T., C.S., and M.M. critically edited the manuscript for consistency and important intellectual information. Elena Toschi is the guarantor of this work and takes full responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of its content and reporting.

Prior Presentations

Data presented in part at ADA Scientific Sessions Virtually in 2021; ATTD Scientific Sessions Virtually 2024.

References:

- Bullard KM, Cowie CC, Lessem SE, et al. Prevalence of Diagnosed Diabetes in Adults by Diabetes Type – United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Mar 30 2018;67(12):359-361. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6712a2

- Boureau AS, Guyomarch B, Gourdy P, et al. Nocturnal hypoglycemia is underdiagnosed in older people with insulin-treated type 2 diabetes: The HYPOAGE observational study. J Am Geriatr Soc. Jul 2023;71(7):2107-2119. doi:10.1111/jgs.18341

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice C. 13. Older Adults: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2025. Diabetes Care. Jan 1 2025;48(Supplement_1):S266-S282. doi:10.2337/dc25-S013

- Brierley EJ, Broughton DL, James OF, Alberti KG. Reduced awareness of hypoglycaemia in the elderly despite an intact counter-regulatory response. QJM. Jun 1995;88(6):439-45.

- Ruedy KJ, Parkin CG, Riddlesworth TD, Graham C, Group DS. Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Older Adults With Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes Using Multiple Daily Injections of Insulin: Results From the DIAMOND Trial. J Diabetes Sci Technol. Nov 2017;11(6):1138-1146. doi:10.1177/1932296817704445

- Pratley RE, Kanapka LG, Rickels MR, et al. Effect of Continuous Glucose Monitoring on Hypoglycemia in Older Adults With Type 1 Diabetes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. Jun 16 2020;323(23):2397-2406. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6928

- Bao S, Bailey R, Calhoun P, Beck RW. Effectiveness of Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Older Adults with Type 2 Diabetes Treated with Basal Insulin. Diabetes Technol Ther. May 2022;24(5):299-306. doi:10.1089/dia.2021.0494

- Weinstock RS, Raghinaru D, Gal RL, et al. Older Adults Benefit From Virtual Support for Continuous Glucose Monitor Use But Require Longer Visits. J Diabetes Sci Technol. Nov 2 2024:19322968241294250. doi:10.1177/19322968241294250

- Toschi E, Slyne C, Sifre K, et al. The Relationship Between CGM-Derived Metrics, A1C, and Risk of Hypoglycemia in Older Adults With Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. Oct 2020;43(10):2349-2354. doi:10.2337/dc20-0016

- Karter AJ, Parker MM, Moffet HH, Gilliam LK, Dlott R. Association of Real-time Continuous Glucose Monitoring With Glycemic Control and Acute Metabolic Events Among Patients With Insulin-Treated Diabetes. JAMA. Jun 8 2021;325(22):2273-2284. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.6530

- Alkabbani W, Cromer SJ, Kim DH, et al. Overall Uptake and Racial, Ethnic, and Socioeconomic Disparities in the Use of Continuous Glucose Monitoring Devices Among Insulin-Treated Older Adults With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. Aug 1 2025;48(8):1377-1385. doi:10.2337/dca25-0006

- Munshi M, Slyne C, Davis D, et al. Use of Technology in Older Adults with Type 1 Diabetes: Clinical Characteristics and Glycemic Metrics. Diabetes Technol Ther. Jan 2022;24(1):1-9. doi:10.1089/dia.2021.0246

- Kahkoska AR, Smith C, Thambuluru S, et al. “Nothing is linear”: Characterizing the determinants and dynamics of CGM use in older adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. Feb 2023;196:110204. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2022.110204

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice C. 7. Diabetes Technology: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2025. Diabetes Care. Jan 1 2025;48(1 Suppl 1):S146-S166. doi:10.2337/dc25-S007

- Danne T, Nimri R, Battelino T, et al. International Consensus on Use of Continuous Glucose Monitoring. Diabetes Care. Dec 2017;40(12):1631-1640. doi:10.2337/dc17-1600

- ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 7. Diabetes Technology: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. Jan 1 2023;46(Suppl 1):S111-S127. doi:10.2337/dc23-S007

- Bergenstal RM, Beck RW, Close KL, et al. Glucose Management Indicator (GMI): A New Term for Estimating A1C From Continuous Glucose Monitoring. Diabetes Care. Nov 2018;41(11):2275-2280. doi:10.2337/dc18-1581

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. Jul 2019;95:103208. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208

- Munshi MN, Segal AR, Slyne C, Samur AA, Brooks KM, Horton ES. Shortfalls of the use of HbA1C-derived eAG in older adults with diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. Oct 2015;110(1):60-65. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2015.07.012

- Beck RW, Connor CG, Mullen DM, Wesley DM, Bergenstal RM. The Fallacy of Average: How Using HbA1c Alone to Assess Glycemic Control Can Be Misleading. Diabetes Care. Aug 2017;40(8):994-999. doi:10.2337/dc17-0636

- Pettus JH, Zhou FL, Shepherd L, et al. Incidences of Severe Hypoglycemia and Diabetic Ketoacidosis and Prevalence of Microvascular Complications Stratified by Age and Glycemic Control in U.S. Adult Patients With Type 1 Diabetes: A Real-World Study. Diabetes Care. Dec 2019;42(12):2220-2227. doi:10.2337/dc19-0830

- Shah VN, Wu M, Foster N, Dhaliwal R, Al Mukaddam M. Severe hypoglycemia is associated with high risk for falls in adults with type 1 diabetes. Arch Osteoporos. Jun 12 2018;13(1):66. doi:10.1007/s11657-018-0475-z

- Simonson GD, Bergenstal RM, Johnson ML, Davidson JL, Martens TW. Effect of Professional CGM (pCGM) on Glucose Management in Type 2 Diabetes Patients in Primary Care. J Diabetes Sci Technol. May 2021;15(3):539-545. doi:10.1177/1932296821998724

- Galindo RJ, Migdal AL, Davis GM, et al. Comparison of the FreeStyle Libre Pro Flash Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM) System and Point-of-Care Capillary Glucose Testing in Hospitalized Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Treated With Basal-Bolus Insulin Regimen. Diabetes Care. Nov 2020;43(11):2730-2735. doi:10.2337/dc19-2073