Dietary Supplements Enhance Inflammation and Oxidative Stress

Dietary Supplementation Improves Markers of Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Endothelial Function in a Healthy Adults

Mahmut Ilker Yilmaz1*, Zeynep Demir2, Muhammet Fatih Demir3, Nilgun Ece Yilmaz4, Awatif M. Abuzgaia5, Abdelbaset Elzagallaai6, David Piskin6, Sinem Tuncer7, Murat Tolga Yilmaz8, Fatih Muhammed Kaya9, Yaprak Demir10, Aysegul Elbir Sahin11, Mustafa Öztürk12, Halit Demir13

1.Epigenetic Health Solutions, Unit of Nephrology, Ankara, Turkey

2.Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA

3.Wake Forest University, Center for Artificial Intelligence Research, Winston-Salem, NC, USA

4.Ankara Training and Research Hospital, Department of Emergency Medicine, Ankara, Turkey

5.Division of Pediatric Rheumatology, Victoria Hospital, University of Western Ontario, London, ON, Canada

6.Physiology and Pharmacology, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Western Ontario, London, Canada

7.Public Health Institution of Turkey, Ankara Turkey

8.Environmental Engineering Department, Engineering Faculty, Atatürk University, Erzurum, Turkey

9.Igdir Hospital, Department of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation, Igdir, Turkey

10.Arztekammer Berlin, Germany

11.Samsun Training and Research Hospital, Clinic of Anesthesiology and Reanimation, Samsun, Türkiye

12.Private Medistate Hospital, Department of Oncology, Istanbul, Turkey

13.Van Yuzuncu Yil University, Department of Biochemistry, Van, Turkey.

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 August 2025

CITATION

Yilmaz, MI., Demir, Z., et al., 2025. Dietary Supplementation Improves Markers of Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Endothelial Function in a Healthy Adults. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(8). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i8.6826

COPYRIGHT

© 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI

https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i8.6826

ISSN

2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Objectives: This study is to investigate the effects of 3 functional food supplements on basic metabolic parameters on 61 healthy adult individuals. The 24-week study was completed with 43 men and 18 adult women. The average age of the participants was 30 ± 9 years.

Methods: In this study, anti-atherosclerotic liquid (AAL)-Morinda citrifolia (3 mL once per day orally) anti-inflammatory capsules (AIC)-Omega-3 (3 capsules once per day orally) extract with antioxidant liquid (AOL)-Blueberry and 21 different red purple fruit vegetables (30 mL once per day orally) have been used. We compared 24 weeks before and after.

Results: The study shows the longitudinal changes of selected parameters in the 61 healthy people that completed the study. Following anti-atherosclerotic liquid (AAL), anti-inflammatory capsules (AIC) and antioxidant liquid (AOL) therapies, asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), malondialdehyde (MDA), pentraxin-3 (PTX3), homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), body mass index (BMI), fasting plasma glucose (FPG), total cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) levels were significantly decreased, while flow-mediated dilation (FMD), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25OHVD), and folic acid levels were significantly increased.

Conclusions: Our results indicated that selected functional food supplements showed strong beneficial effect on selected metabolic parameters.

Keywords: Morinda citrifolia, omega-3, blueberries, inflammation, oxidative stress, healthy people.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disorders, diabetes, obesity, and neurodegenerative conditions remain major public health concerns worldwide. These conditions are typically progressive, often incurable, and tend to become more prevalent with aging. While some chronic diseases can be delayed or prevented through lifestyle changes, others arise independently of behavioral risk factors. In either case, health-damaging behaviors such as smoking, physical inactivity, and poor dietary habits significantly contribute to increased morbidity and mortality in affected populations.

Among the leading chronic conditions, atherosclerosis stands out as one of the most common causes of death globally. It is closely associated with three fundamental and interconnected pathological mechanisms: oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction. These processes not only underlie the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis but also play essential roles in maintaining overall health and vascular homeostasis.

These three basic mechanisms (oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction) play very important key roles. In this study, we conducted a 6-month study on 61 healthy volunteers who had no health problems and were not taking any medication in order to demonstrate the effectiveness of the 3 mechanisms by giving them a food containing nitrate (Morinda citrifolia) related to Nitric Oxide metabolism, an extract obtained from 22 vegetables and fruits with high antioxidant capacity for the management of the oxidative stress process and an omega 3 obtained from salmon and containing astaxanthin and tocotrienol for the proper management of the inflammatory process.

Metabolism produces free radicals or oxidants. The elimination of these is necessary for the systematic functioning of biological processes. Unhealthy eating, smoking, and alcohol consumption increase oxidative stress. Free radicals can be produced within the body, meaning as a by-product of aerobic activity. An individual’s lifestyle and environment also contribute to the increase of free radicals. During normal metabolism, each cell produces about 20 billion oxidants per day. As a defense mechanism, cells produce free radicals such as nitric oxide, superoxide, and H2O2 to fight pathogenic microorganisms. Additionally, oxidants are produced as a result of the breakdown of fatty acids or as a defense against certain chemicals.

Blueberry is a dark blue fruit native to the European basin. Blueberry, a fruit rich in antioxidants, also contains many vitamins and minerals such as iron, phosphorus, calcium, magnesium, manganese and zinc. In this respect, blueberry fruit supports heart health and reduces the risk of cardiovascular diseases, protects bone health by increasing calcium absorption, makes it easier to keep sugar under control, manages blood pressure by balancing blood pressure, lowers cholesterol, strengthens the immune system and makes the body resistant to diseases. Blueberry also has potential benefits in terms of brain health, skin protection and cancer prevention.

Inflammation, known as inflammation, is a response that occurs in everyone and is generated by the immune system to protect the body against various diseases or injuries. Inflammation underlies many healing processes in the body. The cause of inflammation in some individuals may be autoimmune diseases resulting from immune system cells producing antibodies against the body’s other healthy cells and tissues. There is an autoimmune event in the formation of some disorders such as arthritis (joint inflammation) and inflammatory bowel disease. The state of inflammation is studied in two groups: acute and chronic. Acute inflammation typically describes a serious inflammatory condition that occurs over a short period of time. In acute inflammations, the duration is less than 2 weeks, and the symptoms develop quite rapidly. Inflammation that occurs in newly initiated diseases and injuries is acute inflammation.

By producing nitric oxide, which is also vital in healthy individuals, with the right food and by directing the free radicals formed in the body correctly with a food product with strong antioxidant capacity, we have shown an important step in preventing the development of endothelial dysfunction and reducing cardiovascular mortality and morbidity.

Endothelial cells are a type of flat, single-layer epithelium found throughout the vascular system. They play key regulatory roles there. They maintain vascular tone, regulate blood flow, and provide protection against inflammation and thrombosis. However, impaired regulation can result in pathological processes and harmful outcomes. These functions are mediated by molecules such as nitric oxide, endothelin, prostaglandins, and angiotensin II. Endothelial dysfunction is defined as disturbances in the production or action of these mediators, often due to pathological factors or secretory imbalances. Dysfunction of the endothelium is closely associated with the progression of chronic diseases, inflammation, and conditions such as atherosclerosis.

Nitric oxide is naturally produced by the body and affects health in many ways. Because it allows blood to travel effectively and efficiently throughout the body. Its most important function is as a vasodilator. In other words, it relaxes the inner muscles of the blood vessels, allowing them to expand, increasing blood flow and lowering blood pressure. Nitric oxide production is limited in people with heart disease, diabetes and erectile dysfunction.

The organ system that maintains the integrity of the cardiovascular system maintains its integrity and the risk of developing cardiovascular disease is eliminated. The endothelium plays a role in regulating blood flow through nitric oxide production. Loss of endothelial nitric oxide production causes endothelial dysfunction. This loss occurs years before structural changes in the vessels and is associated with cardiovascular risks. All the risk factors that cause the development of cardiovascular disease impair nitric oxide production, and nitric oxide production is suppressed with aging.

Since nitrates can be converted to nitric oxide, eating foods high in natural nitrates can easily and easily increase nitric oxide levels. Research shows that getting nitrates from vegetables is an effective way to improve heart health. Eating more nitrates in your daily diet can help increase nitric oxide levels and exercise performance. The body produces nitric oxide from vitamin C and nitrate-containing components.

Noni is a tropical fruit that grows naturally in volcanic, mineral-rich soils of the Pacific region. Known by its Latin name Morinda citrifolia, noni is considered one of the superfoods. It is rich in vitamins, minerals, isoflavones, terpenes, scopoletin, xeronines, and anthraquinones. Thanks to these bioactive compounds, noni is believed to possess anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antibacterial, antifungal, antihistamine, and anti-aging properties.

Oxidative stress occurs because of an imbalance between free radicals and antioxidants in your body. Molecules containing oxygen with an unequal number of electrons are called free radicals. These uneven electrons in free radicals easily react with other molecules. This situation can lead to large chain chemical reactions in your body. These reactions that can occur in your body are referred to as oxidation. Oxidation is a normal and necessary process that occurs in your body. It can be beneficial and harmful for your body.

Omega 3 is a group of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids that help many functions in the body to be more functional and are used as the building blocks of cell membranes. Omega 3, which comes in various forms, has 3 different types: EPA (eicosatetraenoic acid), DHA (docosahexaenoic acid) and ALA (alpha-linolenic acid). Omega 3, which cannot be produced naturally by the body and is most found in seafood, is taken into the body through food. Omega 3 fatty acids have basic benefits such as strengthening the immune system, reducing inflammatory processes, protecting cardiovascular health, supporting brain health and eye health.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

PARTICIPANTS

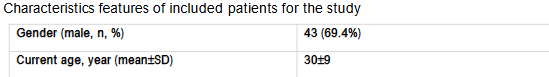

This study conducted with selected patients who referred to the Epigenetic Health Center Outpatient Clinics, Ankara, Turkey during the period September 7th, 2020 – November 7th, 2022. We included patients who were: older than 18 normal estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) treated with an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibiters (ACEI) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), with obesity (BMI >30kg/m2), dyslipidemia (total cholesterol > 280 mg/dl, fasting triglycerides > 180 mg/dl), renal failure, (eGFR <90 ml/min), nephrotic syndrome (urinary protein excretion >3000 mg/day), a history of CVD (medical history, abnormal electrocardiogram, smoking and/or currently or within the last 3 months taking statins). There were 144 healthy people who fulfilled the above inclusion criteria. The mean age of the participants was 30±9 years and 69.4% were male. A total of 61 healthy participants (43 M and 18 F) were recruited for the study.

Study groups were evaluated by standard physical examination, chest X-ray, baseline electrocardiogram, two-dimensional echocardiography, and routine clinical laboratory tests, including liver and kidney function tests and 24-hour urinary protein measurements. Arterial blood pressure was measured in the right arm by mercury sphygmomanometer three times in a resting condition in the morning, and mean values were calculated for diastolic and systolic pressures.

INTERVENTION

In an open-label trial, healthy people were given a Morinda citrifolia (anti-atherosclerotic liquid- AAL-Nitro plus, Amare Global, 3 ml once per day), omega-3 (anti-inflammatory capsules- AIC- Sunset, Amare Global, 3 capsules once per day) and an extract of blueberry and 21 different red purple fruit vegetables (anti-oxidant liquid- AOL- Sunrise, Amare Global, 30 ml once per day) therapies for 24 weeks immediately following baseline measurements. During the study period, serum creatinine and potassium concentrations were measured every 2 weeks, and the dose of Noni, omega-3 and antioxidant therapies were titrated to achieve a serum potassium concentration <5.5 mEq/L. After this period, blood samples were obtained for measurements as shown below. None of healthy people used either dietary supplements or any vitamin supplements. The participants consuming the intervention did not alter their common diet or perform extra physical activity intended to alter metabolic parameters. To be able to reach the standard in the study and not to affect our results in the 6th month, people with similar nutritional and exercise habits were included in the study.

MEASUREMENTS

Blood chemistry: Morning blood samples were collected from patients after 12 hours of fasting. Subjects were asked to refrain from physical activity for at least 30 minutes prior to the blood draw. In addition to routine clinical laboratory tests, serum asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), malondialdehyde (MDA), copper zinc-superoxide dismutase (CuZn-SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), high sensitivity C reactive protein (hsCRP) and pentraxin 3 (PTX3) concentrations and basal insulin levels were analyzed from healthy people. After the intervention period, blood samples were obtained for the measurement of serum asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), malondialdehyde (MDA), copper zinc-superoxide dismutase (CuZn-SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), high sensitivity C reactive protein (hsCRP) and pentraxin 3 (PTX3) concentration. The measurement of total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and fasting plasma glucose (FPG) was performed by enzymatic colorimetric method with Olympus AU 600 auto analyzer using reagents from Olympus Diagnostics, GmbH (Hamburg, Germany). Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol formula.

Serum basal insulin values were determined by the coated tube method (DPC-USA). Insulin resistances index Homeostasis Model Assessment-Insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was computed with the formula: (HOMA-IR) = fasting plasma glucose (FPG) (mg/dl) x immunoreactive insulin (IRI) (µIU/ml)/405. All samples were run in triplicates.

Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) measurements: Measurements of serum asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) were done using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), as described by Chen et al. In brief, 20 mg of 5-sulfosalisilic acid (5-SSA) was added to 1 ml serum and the mixture was left in an ice-bath for 10 min. The precipitated protein was removed by centrifugation at 2000 g for 10 min. Ten micro liters of the supernatant which was filtered through a 0.2 µm filter was mixed with 100 µl of derivatization reagent (prepared by dissolving 10 mg o-phtaldialdehyde in 0.5 ml of methanol, 2 ml of 0.4 M borate buffer (pH 10.0) and 30 µl of 2-mercaptoethanol) and then injected into the chromatographic system. Separation of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) was achieved with a 150×4 mm I.D. Nova-pak C18 column with a particle size of 5 µm (Waters, Millipore, Milford, MA, USA) using 50 mM sodium acetate (pH 6.8), methanol and tetrahydrofurane as mobile phase (A, 82:17:1; B, 22:77:1) at a flowrate of 1.0 ml/min. The area of peak detected by the fluorescent detector (Ex: 338 nm) was used as quantification. The variability of the method was less than 7%, and the detection limit of the assay was 0.01 µM.

High sensitive C reactive protein (hsCRP) assessment: Briefly, serum samples were diluted with a ratio of 1/101 with the diluent solution. Calibrators, kit controls and serum samples were all added on each micro well with an incubation period of 30 minutes. After 3 washing intervals 100 µL enzyme conjugate (peroxidase labeled anti-CRP) was added on each micro well for additional 15 minutes incubation in room temperature in dark. The reaction was stopped with a stop solution and photometric measurement was performed at the 450 nm wavelength.

Plasma Pentraxin 3 (PTX-3) measurements: Plasma pentraxin 3 (PTX 3) concentration was measured posteriori from frozen samples by using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Perseus Proteomics Inc, Japan).

Erythrocyte antioxidant capacity: Blood samples were drawn after overnight fasting from the antecubital vein and collected in heparinized polypropylene tubes. Plasma and erythrocytes were separated and used for measuring trace elements and antioxidant enzymes. Erythrocyte copper zinc-superoxide dismutase (CuZn-SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) activity was measured in a UV-VIS Recording Spectrophotometer (UV-2100S; Shimadzu Co., Kyoto, Japan) as previously described by Aydin et al. Erythrocyte zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), and iron (Fe) levels were measured by flame atomic absorption spectrophotometry using a Varian atomic absorption spectrophotometer (30/40 model; Varian Techtron Pty Ltd., Victoria, Australia). The wavelengths used were as follows: 213.9-nm wavelengths for Zn, 324.7-nm wavelengths for Cu, and 248.3-nm wavelengths for Fe. Results were expressed as units per milliliter for copper zinc-superoxide dismutase (CuZn-SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) and as micrograms per milliliter for Zn, Fe, and Cu.

Erythrocyte malondialdehyde (MDA) level measurement: Erythrocyte malondialdehyde (MDA) levels were determined on erythrocyte lysate obtained after centrifugation and in accordance with the method described by Jain. After the reaction of thiobarbituric acid with malondialdehyde (MDA), the reaction product was measured spectrophotometrically at 532 nm. Tetrametoxypropane solution was used as standard. Malondialdehyde (MDA) levels of erythrocyte were expressed as nanomoles per milliliter.

Serum vitamin B12 measurement: Serum vitamin B12 was measured in adults 20 years and older using the fully automated electrochemiluminescence immunoassay on the Roche Elecsys 170 System (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Vials were stored under appropriate frozen (<-20°C) conditions until they were shipped to National Center for Environmental Health for testing. The lower limit of detection (LLOD) for vitamin B12 was 30 pg/mL (i.e., 22.14 pmol/L). The coefficient of variation for this assay was lower than 4%.

Serum folic acid measurement: Serum folic acid was studied using an automated cell counter and chemiluminescence. A serum folic acid level of less than 4 ng/ml was considered to indicate a folate deficiency (Roche Elecsys 170 System (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN).

Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25OHVD) measurement: To measure 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25OHVD) we used high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) kits following the manufacturer’s instructions (ImmuChrom GmbH, Heppenheim, Germany. Quantification of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 was made by HPLC system with UV (264 nm) detector (Thermo Electron, San Jose, CA, USA). The intra-assay coefficient of variation was 0.9-2.9%, and the calculated inter-assay coefficient of variation was 1.7-3.9% and recovery was 91%.

Serum magnesium measurement: The Beckman Coulter AU System Magnesium procedure utilizes a direct method in which magnesium forms a colored complex with xylidyl blue in a strongly basic solution, where calcium interference is eliminated by glycoletherdiamine- N,N,N’,N’-tetra acetic acid (EDTA) (Beckman Coulter, Inc., 250 S. Kraemer Blvd. Brea, CA 92821, USA). The magnesium levels were expressed in milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL). The within run precision for serum samples was less than 1.26% CV and total precision is less than 1.53% CV.

Assessment of endothelial dysfunction: The determination of endothelial dysfunction was performed according to the method described by Celemajer et al. Measurements were made by a single observer using an ATL 5000 ultrasound system (Advanced Technology Laboratories Inc., Bothell, WA., USA) with a 12-Mhz probe. All vasoactive medications were withheld for 24 hours before the procedure. The subjects remained at rest in the supine position for at least 15 min before comfortably immobilized in the extended position to allow consistent recording of the brachial artery 2 4 cm above the antecubital fossa. Three adjacent measurements of end-diastolic brachial artery diameter were made from single 2-D frames. All ultrasound images were recorded on S-VHS videotape for subsequent blinded analysis. The maximum flow-mediated dilation (FMD) diameters were calculated as the average of the three consecutive maximum diameter measurements after hyperemia. The flow-mediated dilation (FMD) levels were then calculated as the percent change in diameter compared with baseline resting diameters.

ENDPOINTS

The primary endpoint was flow-mediated dilation (FMD) percentage change in cohort at the 24th week of the study. Secondary endpoints included status of the antioxidant parameters, inflammatory marker high sensitivity C reactive protein (hsCRP), endothelial biomarkers (malondialdehyde-ADMA, Homeostasis Model Assessment-HOMA), and serum lipid profile.

STATISTICAL METHODS

With a study population of 61 healthy people and a standard deviation of the difference of flow-mediated dilation (FMD) change after therapies of 0.50, our study has a 90% power to detect as statistically significant with a p value<0.001 a flow-mediated dilation (FMD) change of 0.2% or greater. Non-normally distributed variables were expressed as median (range) and normally distributed variables as mean ± SD. A p value <0.05 was statistically significant. Kolmogorov Smirnov test was used for analysis distribution of data. All statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) statistical package.

RESULTS

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS

The mean age of the participants was 30±9 years and 69.4% were male. (Table 1) Baseline clinical and laboratory characteristics of selected parameters in the 61 participants presented in Table 2.

THE EFFECT OF ANTI-ATHEROSCLEROTIC LIQUID (AAL), ANTI-INFLAMMATORY CAPSULES (AIC) AND ANTIOXIDANT LIQUID (AOL) THERAPIES

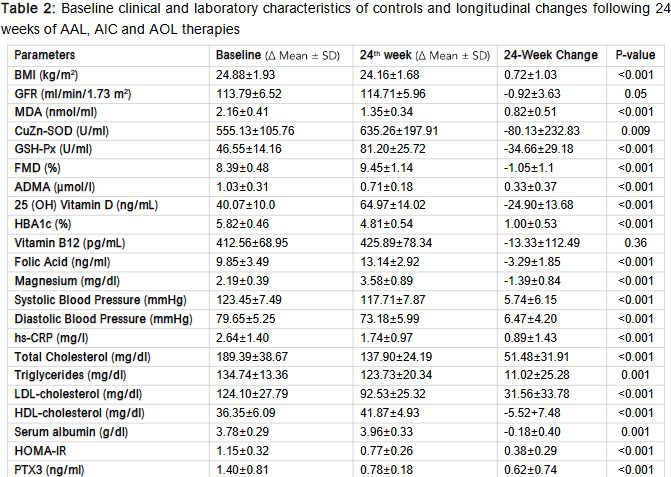

Table 2 shows the longitudinal changes of selected parameters in the 61 participants that completed the study. The results are displayed across major categories, such as metabolic control, fat metabolism, blood vessel function, oxidative stress and inflammation, and vitamin and mineral levels. (Figure 1-5). After 24 weeks of anti-atherosclerotic liquid (AAL), anti-inflammatory capsules (AIC) and antioxidant liquid (AOL) therapies, participants demonstrated significant improvements in various clinical parameters. The results showed significant improvements in cardiometabolic health, as indicated by reductions in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), body mass index (BMI), and blood pressure, along with advances in lipid profiles and endothelial function. Additionally, elevated antioxidant enzyme activity and decreased inflammatory marker levels indicate reduced systemic oxidative stress and inflammation. Collectively, these results underscore the varied healing capabilities of the measures in lowering the likelihood of long-term metabolic and cardiovascular illnesses.

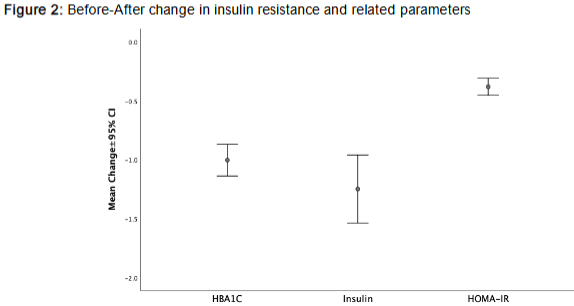

1. Metabolic Parameters:

After 24 weeks of therapy, significant metabolic improvements were observed (p<0.001), suggesting weight reduction likely due to lifestyle or therapeutic interventions. Insulin sensitivity improved, as evidenced by a significant reduction in homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) (Δ = 0.38±0.29).

Glycemic control was also enhanced, with glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels decreasing from 5.82% to 4.81% (p<0.001). Although serum albumin levels showed a slight but statistically significant decrease (p=0.001), this change may reflect minor alterations in protein metabolism or systemic inflammation, with limited clinical relevance.

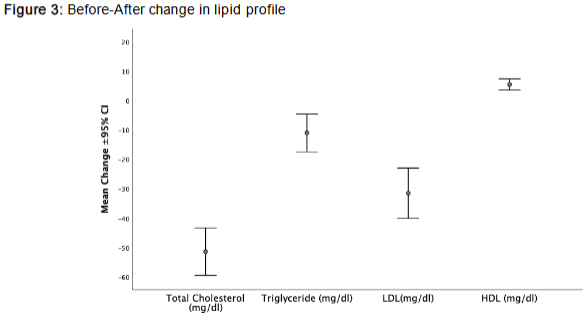

2. Lipid Profile and Cardiovascular Risk:

Total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL), and triglyceride levels significantly decreased (all p<0.001), indicating a favorable lipid-lowering effect. Notably, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) increased by 5.52 mg/dL (p<0.001), further improving the atherogenic profile. Collectively, these changes suggest a reduced cardiovascular risk over the course of the 24-week intervention.

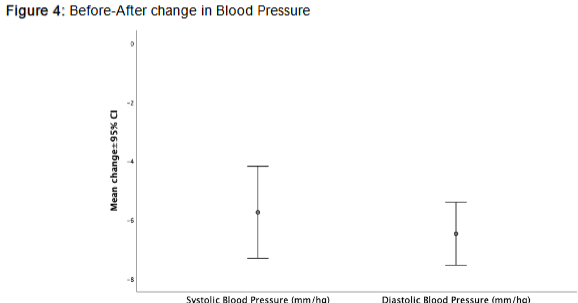

3. Vascular Function and Blood Pressure:

Systolic and diastolic blood pressures significantly decreased (Δ = -5.74±6.15 mmHg, respectively; p<0.001), indicating improved hemodynamic stability.

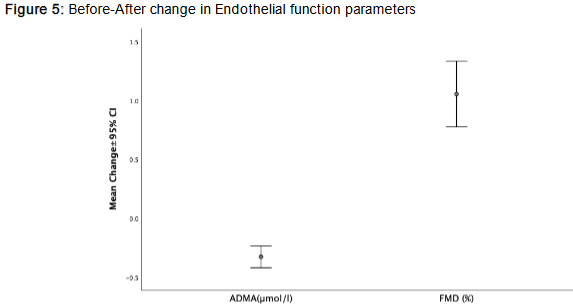

Additionally, flow-mediated dilation (FMD) improved (Δ = 1.05±1.1%, p<0.001), reflecting enhanced endothelial function. This was further supported by a significant reduction in asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) levels (p<0.001), a marker of endothelial dysfunction, collectively suggesting improved vascular health following the intervention.

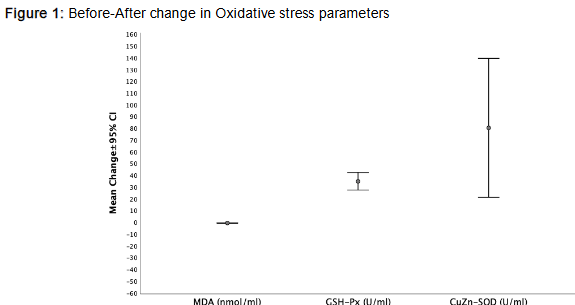

4. Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Markers:

Markers of oxidative stress and inflammation showed significant improvement after the intervention. Malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, indicative of lipid peroxidation, decreased markedly (p<0.001), while antioxidant enzyme activities copper zinc-superoxide dismutase (CuZn-SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) increased significantly (p=0.009 and p<0.001, respectively), suggesting enhanced oxidative defense. Inflammatory markers also improved, with hs-CRP decreasing by 0.89 mg/L (p<0.001) and pentraxin-3 (PTX3) showing a significant decline (p<0.001), collectively supporting a robust anti-inflammatory effect.

5. Micronutrient and Vitamin Status:

Micronutrient and vitamin status improved following the intervention. Serum 25(OH) vitamin D levels increased significantly from 40.07 ng/mL to 64.97 ng/mL (p<0.001), indicating enhanced vitamin D status, likely due to supplementation or increased sun exposure. Folic acid and magnesium levels also rose significantly (p<0.001), potentially contributing to improved metabolic and vascular function. In contrast, vitamin B12 levels did not change significantly (p=0.36), suggesting minimal impact on B12 status. Additionally, no significant changes were observed in glomerular filtration rate (GFR), hemoglobin (Hb), hematocrit (Hct), calcium (Ca), or parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels over the course of the study.

Overall, the 24-week supplementation with anti-atherosclerotic liquid (AAL), anti-inflammatory capsules (AIC) and antioxidant liquid (AOL) was associated with broad improvements in metabolic, vascular, oxidative, and inflammatory parameters, without negatively impacting renal or hematological markers, highlighting the potential health-supporting benefits of these natural compounds in healthy individuals.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that 24 weeks of dietary supplementation with anti-atherosclerotic liquid (AAL), anti-inflammatory capsules (AIC) and antioxidant liquid (AOL) formulations led to significant improvements across multiple physiological systems in healthy adults. Improvements were observed in metabolic control, lipid profile, vascular function, oxidative stress, and inflammatory markers all without adverse effects on renal, hematologic, or micronutrient balance. Natural compounds such as Noni fruit, Omega-3 fatty acids and blueberry have important roles in managing inflammation, oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction, which are the three main mechanisms of chronic diseases.

Our study was intentionally designed to evaluate a multi-targeted nutritional strategy. Chronic diseases are complex, stemming from the interplay of various pathological processes. Therefore, we hypothesized that a combination of supplements (one targeting nitric oxide bioavailability (AAL-anti-atherosclerotic liquid), one targeting systemic inflammation (AIC-anti-inflammatory capsules), and one providing broad antioxidant support (AOL-antioxidant liquid)) would yield a more comprehensive and synergistic benefit than any single agent alone. This approach aims to restore homeostasis by addressing these interconnected pathways simultaneously.

IMPROVEMENTS IN ENDOTHELIAL DYSFUNCTION

Among the most significant outcomes was the improvement in endothelial function, demonstrated by an increase in flow-mediated dilation (FMD) and a reduction in asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), a known endogenous inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase and marker of endothelial dysfunction. This suggests enhanced nitric oxide bioavailability, a critical factor in maintaining vascular tone and preventing atherogenesis. The use of Morinda citrifolia (noni) in anti-atherosclerotic liquid (AAL), a nitrate-rich fruit with known vasodilatory and antioxidant properties, likely contributed to these vascular benefits. Noni fruit also improves endothelial function by protecting vascular walls and promoting vasodilation. Blueberries promote vasodilation and reduce arterial stiffness by increasing nitric oxide production in vascular endothelial cells. This effect was observed in 12-week studies, especially in postmenopausal women. Omega-3 also improves endothelial function by increasing eNOS activity and supporting nitric oxide production. This contributes to maintaining vascular health.

The observed improvement in flow-mediated dilation (FMD) is particularly noteworthy. As a functional measure of endothelial health, even modest increases in flow-mediated dilation (FMD) are associated with a lower risk of future cardiovascular events. The corresponding decrease in asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), a competitive inhibitor of the enzyme that produces nitric oxide, provides a plausible biochemical mechanism for this improvement. Together, these findings suggest a tangible restoration of vascular function that could be crucial for long-term cardiovascular health maintenance.

REDUCTION IN OXIDATIVE STRESS

The antioxidant liquid (AOL) formulation, composed of 22 fruits and vegetables high in antioxidants, appears to have contributed to reduced oxidative stress, as evidenced by decreased malondialdehyde (MDA) levels and increased antioxidant enzyme activity (copper zinc-superoxide dismutase (CuZn-SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px)). These changes align with the antioxidant theory of chronic disease prevention, which posits that polyphenols and flavonoids mitigate free radical damage and cellular aging. Similar outcomes have been observed in studies evaluating berry fruits and polyphenol-rich supplements on oxidative stress markers. Noni fruit reduces cellular damage by neutralizing free radicals and lowering overall oxidative stress. Blueberry components reduce oxidative stress by neutralizing reactive oxygen species (ROS). This protects the vascular walls and reduces the risk of atherosclerosis. Omega-3 fatty acids reduce oxidative stress by increasing the activity of antioxidant enzymes and suppressing NADPH oxidase activity. These mechanisms help protect endothelial cells.

It is critical to view these findings not in isolation, but as part of a connected physiological cascade. The reduction in oxidative stress is a key upstream event, as excess reactive oxygen species are known to both trigger pro-inflammatory signaling and quench the nitric oxide needed for healthy endothelial function. By mitigating oxidative stress, this intervention likely interrupted a vicious cycle that perpetuates both inflammation and vascular damage.

ATTENUATION OF INFLAMMATION

Inflammation, another central mechanism in chronic disease pathophysiology, was significantly attenuated. Both high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) and pentraxin-3 (PTX3) levels decreased after supplementation, suggesting systemic anti-inflammatory effects. The antioxidant liquid (AOL) formulation and omega-3 based supplement containing Eicosatetraenoic acid (EPA), Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), astaxanthin, and tocotrienols is likely responsible for this outcome. Marine omega-3s are well documented for reducing inflammatory cytokines and improving vascular function, while astaxanthin and tocotrienols add synergistic antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. Noni fruit reduces inflammation by inhibiting enzymes such as cyclooxygenase (COX-2) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). This effect may be beneficial in the management of arthritis and other inflammatory conditions. Blueberry components also reduce the production of inflammatory cytokines by suppressing inflammatory pathways such as NF-κB. This mechanism plays a role in the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Omega-3 fatty acids have positive effects on cardiovascular and metabolic health by targeting inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction. Omega-3 fatty acids reduce systemic inflammation by reducing inflammatory markers such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP). This effect has been confirmed in meta-analyses in individuals with heart disease.

ASSOCIATED IMPROVEMENTS IN CARDIOMETABOLIC HEALTH

Additionally, reductions in blood pressure, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL), and triglyceride levels accompanied by increased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) indicate improved cardiometabolic health. These findings are consistent with previous literature highlighting the lipid-lowering and antihypertensive effects of polyphenol and nitrate rich foods. Metabolic parameters also improved significantly, with reductions in body mass index (BMI), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), and homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) indicating better glycemic regulation and insulin sensitivity. These changes may reflect not only the biochemical effects of the supplements but also possible improvements in metabolic flexibility and mitochondrial function areas increasingly linked to cardiometabolic resilience. Notably, the interventions improved serum vitamin D, magnesium, and folic acid levels, while maintaining stable values for vitamin B12, calcium, and parathyroid hormone (PTH). No adverse changes were observed in renal markers (e.g., GFR), hemoglobin, or hematocrit, underscoring the safety of the supplementation over 24 weeks.

STRENGTHS, LIMITATIONS, AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The merits of this study are manifold, including its emphasis on a population that is free of medication and in good health; its thorough evaluation of metabolic, vascular, and biochemical endpoints; and its employment of objective biomarkers such as flow-mediated dilation (FMD), malondialdehyde (MDA), and pentraxin-3 (PTX3). However, limitations include the lack of a placebo control group, potential dietary and lifestyle confounders, and the relatively short follow-up period. The study population was recruited from a single center, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. While the study’s designers intended to assess health promotion rather than disease treatment, these findings raise important questions about the role of targeted dietary supplementation in the early prevention of chronic disease.

Furthermore, the 24-week follow-up period is sufficient to observe changes in biomarkers, but longer-term studies are required to determine if these improvements translate into a reduced incidence of clinical events. This study is the use of a combined supplement intervention. While this reflects a common approach in nutritional strategies, it prevents us from attributing the observed effects to a single supplement or ingredient. The study was designed to assess the efficacy of the combined protocol, and future research would be necessary to disentangle the specific contributions of each component.

In the future, studies should use a random, placebo-controlled design with more people and longer follow-up to confirm these results and see long-term results. Clarification of the interaction of these natural compounds at the cellular and molecular levels is also within the capacity of mechanistic studies.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this study provides evidence that a 24-week dietary supplementation course with AAL, AIC, and AOL improves metabolic health markers, vascular function, oxidative balance, and inflammation markers in healthy individuals. These findings support the potential of targeted nutritional strategies. These strategies can help maintain cardiometabolic health. They can also help prevent the onset of chronic disease.

Conflict of Interest Statement:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Statement:

This study was supported by Amare Global Company.

Acknowledgements:

None.

References:

- Yilmaz MI, Romano M, Basarali MK, et al. The Effect of Corrected Inflammation, Oxidative Stress and Endothelial Dysfunction on Fmd Levels in Patients with Selected Chronic Diseases: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Sci Rep. Jun 2 2020;10(1):9018. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-65528-6

- Godo S, Shimokawa H. Endothelial Functions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. Sep 2017;37(9):e108-e114. doi:10.1161/atvbaha.117.309813

- Senoner T, Dichtl W. Oxidative Stress in Cardiovascular Diseases: Still a Therapeutic Target? Nutrients. Sep 4 2019;11(9) doi:10.3390/nu11092090

- Fergus-Lavefve L, Howard L, Adams SH, Baum JI. The Effects of Blueberry Phytochemicals on Cell Models of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. Adv Nutr. Aug 1 2022;13(4):1279-1309. doi:10.1093/advances/nmab137

- Yilmaz M, Ozturk M, Demir Z, et al. A Different Approach to Malnutrition-Related Appetite and Weight Loss in Cancer Patients: Is Saturation Enough at The Cell Level? Medical Research Archives. 04/01 2025;13 doi:10.18103/mra.v13i3.6419

- Arulselvan P, Fard MT, Tan WS, et al. Role of Antioxidants and Natural Products in Inflammation. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:5276130. doi:10.1155/2016/5276130

- Deanfield JE, Halcox JP, Rabelink TJ. Endothelial function and dysfunction: testing and clinical relevance. Circulation. Mar 13 2007;115(10):1285-95. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.106.652859

- Romano M, Garcia-Bournissen F, Piskin D, et al. Anti-Inflammatory, Antioxidant, and Anti-Atherosclerotic Effects of Natural Supplements on Patients with FMF-Related AA Amyloidosis: A Non-Randomized 24-Week Open-Label Interventional Study. Life (Basel). Jun 15 2022;12(6) doi:10.3390/life12060896

- Chaudron Z, Nicolas-Francès V, Pichereaux C, et al. Nitric oxide production and protein S-nitrosation in algae. Plant Sci. Jun 2025;355:112472. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2025.112472

- Lin YL, Chang YY, Yang DJ, Tzang BS, Chen YC. Beneficial effects of noni (Morinda citrifolia L.) juice on livers of high-fat dietary hamsters. Food Chem. Sep 1 2013;140(1-2):31-8. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.02.035

- West BJ, Deng S, Isami F, Uwaya A, Jensen CJ. The Potential Health Benefits of Noni Juice: A Review of Human Intervention Studies. Foods. Apr 11 2018;7(4) doi:10.3390/foods7040058

- Sies H. Oxidative stress: a concept in redox biology and medicine. Redox Biol. 2015;4:180-3. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2015.01.002

- Shahidi F, Ambigaipalan P. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Their Health Benefits. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol. Mar 25 2018;9:345-381. doi:10.1146/annurev-food-111317-095850

- Ishihara T, Yoshida M, Arita M. Omega-3 fatty acid-derived mediators that control inflammation and tissue homeostasis. Int Immunol. Aug 23 2019;31(9):559-567. doi:10.1093/intimm/dxz001

- Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. Jun 1972;18(6):499-502.

- Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. Jul 1985;28(7):412-9. doi:10.1007/bf00280883

- Chen BM, Xia LW, Zhao RQ. Determination of N(G),N(G)-dimethylarginine in human plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl. May 9 1997;692(2):467-71. doi:10.1016/s0378-4347(96)00531-2

- Yilmaz MI, Stenvinkel P, Sonmez A, et al. Vascular health, systemic inflammation and progressive reduction in kidney function; clinical determinants and impact on cardiovascular outcomes. Nephrol Dial Transplant. Nov 2011;26(11):3537-43. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfr081

- Aydin A, Orhan H, Sayal A, Ozata M, Sahin G, Işimer A. Oxidative stress and nitric oxide related parameters in type II diabetes mellitus: effects of glycemic control. Clin Biochem. Feb 2001;34(1):65-70. doi:10.1016/s0009-9120(00)00199-5

- Sun Y, Sun M, Liu B, et al. Inverse Association Between Serum Vitamin B12 Concentration and Obesity Among Adults in the United States. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:414. doi:10.3389/fendo.2019.00414

- Yilmaz MI, Sonmez A, Saglam M, et al. FGF-23 and vascular dysfunction in patients with stage 3 and 4 chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. Oct 2010;78(7):679-85. doi:10.1038/ki.2010.194

- Kanbay M, Yilmaz MI, Apetrii M, et al. Relationship between Serum Magnesium Levels and Cardiovascular Events in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients. American Journal of Nephrology. 2012;36(3):228-237. doi:10.1159/000341868

- Celermajer DS, Sorensen KE, Gooch VM, et al. Non-invasive detection of endothelial dysfunction in children and adults at risk of atherosclerosis. Lancet. Nov 7 1992;340(8828):1111-5. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(92)93147-f

- Yilmaz MI, Carrero JJ, Martín-Ventura JL, et al. Combined therapy with renin-angiotensin system and calcium channel blockers in type 2 diabetic hypertensive patients with proteinuria: effects on soluble TWEAK, PTX3, and flow-mediated dilation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. Jul 2010;5(7):1174-81. doi:10.2215/cjn.01110210

- Böger RH. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) and cardiovascular disease: insights from prospective clinical trials. Vasc Med. Jul 2005;10 Suppl 1:S19-25. doi:10.1177/1358836×0501000104

- Lundberg JO, Gladwin MT, Ahluwalia A, et al. Nitrate and nitrite in biology, nutrition and therapeutics. Nat Chem Biol. Dec 2009;5(12):865-9. doi:10.1038/nchembio.260

- Yilmazer N, Coskun C, Gurel-Gurevin E, Yaylim I, Eraltan EH, Ikitimur-Armutak EI. Antioxidant and Anti-inflammatory Activities of a Commercial Noni Juice revealed by Carrageenan-induced Paw Edema. Pol J Vet Sci. Sep 1 2016;19(3):589-595. doi:10.1515/pjvs-2016-0074

- Woolf EK, Terwoord JD, Litwin NS, et al. Daily blueberry consumption for 12 weeks improves endothelial function in postmenopausal women with above-normal blood pressure through reductions in oxidative stress: a randomized controlled trial. Food & Function. 2023;14(6):2621-2641. doi:10.1039/D3FO00157A

- Visioli F, Lastra CADL, Andres-Lacueva C, et al. Polyphenols and Human Health: A Prospectus. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2011/07/01 2011;51(6):524-546. doi:10.1080/10408391003698677

- Manach C, Scalbert A, Morand C, Rémésy C, Jiménez L. Polyphenols: food sources and bioavailability. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004/05/01/ 2004;79(5):727-747. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/79.5.727

- Del Bo C, Martini D, Porrini M, Klimis-Zacas D, Riso P. Berries and oxidative stress markers: an overview of human intervention studies. Food Funct. Sep 2015;6(9):2890-917. doi:10.1039/c5fo00657k

- Najjar RS, Mu S, Feresin RG. Blueberry Polyphenols Increase Nitric Oxide and Attenuate Angiotensin II-Induced Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Signaling in Human Aortic Endothelial Cells. Antioxidants (Basel). Mar 23 2022;11(4) doi:10.3390/antiox11040616

- Yamagata K. Prevention of Endothelial Dysfunction and Cardiovascular Disease by n-3 Fatty Acids-Inhibiting Action on Oxidative Stress and Inflammation. Curr Pharm Des. 2020;26(30):3652-3666. doi:10.2174/1381612826666200403121952

- Calder PC. Omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory processes. Nutrients. Mar 2010;2(3):355-374. doi:10.3390/nu2030355

- Serhan CN. Pro-resolving lipid mediators are leads for resolution physiology. Nature. Jun 5 2014;510(7503):92-101. doi:10.1038/nature13479

- Ambati RR, Phang SM, Ravi S, Aswathanarayana RG. Astaxanthin: sources, extraction, stability, biological activities and its commercial applications–a review. Mar Drugs. Jan 7 2014;12(1):128-52. doi:10.3390/md12010128

- Aggarwal BB, Sundaram C, Prasad S, Kannappan R. Tocotrienols, the vitamin E of the 21st century: its potential against cancer and other chronic diseases. Biochem Pharmacol. Dec 1 2010;80(11):1613-31. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2010.07.043

- Ibrahim Mohialdeen Gubari M. Effect of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation on markers of inflammation and endothelial function in patients with chronic heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). Jun 5 2024;70(6):171-177. doi:10.14715/cmb/2024.70.6.26

- Basu A, Rhone M, Lyons TJ. Berries: emerging impact on cardiovascular health. Nutr Rev. Mar 2010;68(3):168-77. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00273.x

- Visioli F, Davalos A. Polyphenols and cardiovascular disease: a critical summary of the evidence. Mini Rev Med Chem. Dec 2011;11(14):1186-90. doi:10.2174/13895575111091186

- Petersen KF, Shulman GI. Etiology of insulin resistance. Am J Med. May 2006;119(5 Suppl 1):S10-6. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.01.009