Enhancing Islet Transplantation with MSC and EC Co-Transplantation

Co-transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells and endothelial cells with islet grafts: A strategy to improve post-tx engraftment of pancreatic islets

Raza Ali Naqvi ¹*, Amar Singh ²*, Afsar Naqvi ¹, Priyadarshini M ³, Devanjan Dey ²

¹ Department of Periodontics, College of Dentistry, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States.

² Department of Surgery, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, United States.

³ Department of Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States.

*E-mail: [email protected] *[email protected]

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 28 February 2025

CITATION Naqvi, RA., Singh, A., et al., 2025. Co-transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells and endothelial cells with islet grafts: A strategy to improve post-tx engraftment of pancreatic islets. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(2). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i2.6230

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i2.6230

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

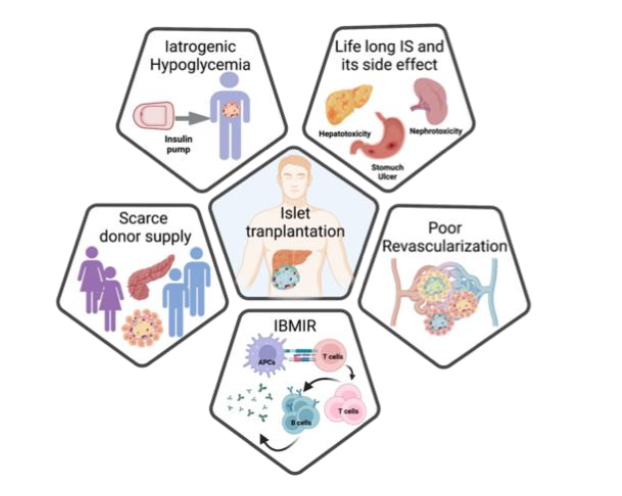

Though islet transplantation is now being considered as a gold standard to cure type 1 diabetes in patients without the threat of unaware hypoglycemia and severe hypoglycemia episode, post-transplantation islet loss due to the loss of intra-islet vasculature during the islet isolation process compromises the full functionality of the transplanted islet mass. Therefore, besides instant blood-mediated inflammatory reaction (IBMIR) induced loss within the first 60 minutes in intraportal vein, two weeks avascular window, prior to adequate vascularization, is responsible for further loss of islets due to hypoxia induced necrosis. Burgeoning evidences demonstrated that using omentum or kidney capsules we can overcome the IBMIR. This review first summarizes the post-transplantation islet loss till day 14 due to the absence of islet vascularization and then elucidates the methods used to restore the post-IBMIR islet loss. Co-transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells and endothelial cells with the islets appeared to be a better approach to overcome the challenges in islet transplantation.

Keywords:

Type 1 diabetes (T1D), Islet transplantation, Co-transplantation, Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), Endothelial cells (ECs), Instant blood mediated immune reaction (IBMIR), Post-transplantation islet loss.

1. Introduction

Autoimmune destruction of insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas and resultant hyperglycemia are the salient features of this devastating type 1 diabetes (T1D). The exact etiology and pathogenesis of this disease is ironically unknown. Global burden of Type 1 diabetes is increasing rapidly. Recently, Gregory et al, reported ~8.4 million individuals worldwide with type 1 diabetes with various age groups: 1·5 million aged 20 years, 5·4 million aged 20-59 years, 1·6 million aged in 2021. Although genetic predisposition suggested more than 40 loci at different chromosomes are associated with T1D predisposition, the majority of genetically predisposed individuals do not necessarily show overt T1D. Though insulin is considered a life savior drug to treat T1D patients with overt hyperglycemia, insulin-induced iatrogenic hypoglycemia has emerged as a real challenge to this treatment modality. Human islet allo-transplantation under immunosuppressive protocol turn out to be a medical miracle as 7/7 patients in this treatment achieved irreversible insulin independence for 5 years. This protocol is based on steroid-free immune suppressive regimens. Results of this protocol were successfully reproduced in multicentric international trials in 2006 and it has been widely accepted as state-of-art technology to treat type 1 diabetics. In this protocol, Tacrolimus (Tac) is regarded as a mainstay immunosuppressant to prevent islet specific post transplantation auto- and allo immunity. Prolonged exposure to Tac (calcineurin inhibitor) eventually leads to 1) nephrotoxicity, 2) impairment in insulin secretion and biosynthesis, 3) mitochondrial arrest and 4) decrease in post-transplant vascularization. To overcome the deleterious effects of Tac, group supplemented the islets with antiaging glycopeptide (AAGP). AAGP supplementation significantly improved islet survival (Tac+ vs. Tac+AAGP, 31.5% vs. 67.6%), augmented insulin secretion (area under the curve: Tac+ vs. Tac+AAGP, 7.3 vs. 129.2 mmol/L/60 min), ameliorated oxidative stress, enhanced insulin exocytosis, reduced apoptosis, and improved engraftment in mice. Furthermore, the use of pig islets has promised to resolve islet donor shortages with good quality islets. Long-term survival of both adult pig islets and neonatal pig islets promised to solve most of the issues pertaining to insufficient cadaveric islets but PERV virus epidemiology in pigs is yet to be resolved to apply this hyperglycemia curing regimen in the clinic in the future.

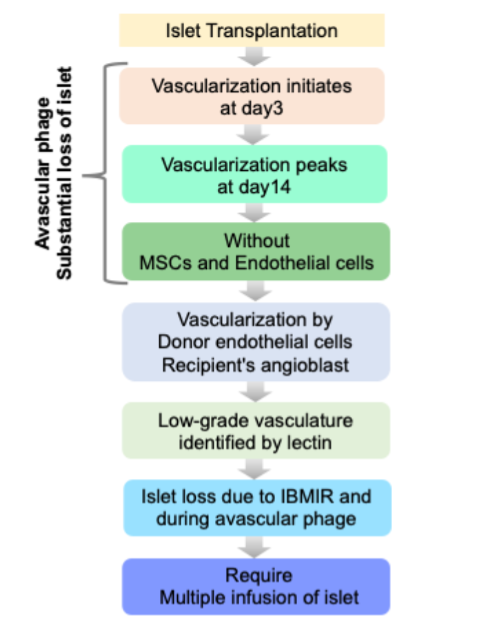

2. Poor engraftment of islet graft

Owing to recent advancements in islet isolation and immunosuppression regimens, pancreatic islet transplantation holds great promise for a long-term cure of T1D without recurrent hypoglycemic episodes. Ironically, 60-70% of islet mass is lost during the initial days of transplantation, and normoglycemia is maintained by 20-30% leftover islets. To maintain the optimal delivery of oxygen and other necessary nutrients for sufficient dispersal of secreted hormones, pancreatic islets maintain exceptional glomerular-like angioarchitecture with a high blood perfusion rate: 5-7 ml min-1·g-1 tissue. The disruption of islet endothelium and endogenous islet-angioarchitecture during the islet isolation process led to the purified transplantable islets as an avascular entity. Thus, there is a crucial need for rapid vascularization for the survival and engraftment of the islets to maintain normoglycemia in T1D patients. To improvise the post-transplantation vascularization, D. group has made commendable efforts. The group has have transplanted pancreatic islets onto the vascular bed of striated muscles in the dorsal skinfold chamber in the Syrian golden model. Both in iso- and xeno-islets, the first signs of re-vascularization appeared on 2-4 days post-tx. Early vascularization in this study was characterized by: 1) the presence of sinusoidal vessels and, the protrusion of capillary sprouts from the venular segments, 2) post capillary venules of the striated muscle vascular bed (which further branched and eventually formed an initial microvascular network). Later in the same year, O group in Sweden further substantiated these findings. They have transplanted fetal porcine islet-like cell clusters (ICC) and used laser-Doppler flowmetry and Hsp70 levels (beta cell stress) as read-outs of initiation of revascularization. They have demonstrated that revascularization of subcapsular ICC graft was initiated rapidly within 3 days post-tx with the concomitant lowering of Hsp70 levels. Furthermore, it was demonstrated by Davalli et al., that post-tx re-vascularization begins on day 3 and peaks on day 14. Therefore, the transplanted islets were in an avascular state till day 14 and succumb to undergo beta cell necrosis. The potential of this newly formed vascular bed to meet the requirements of highly metabolically active beta cells is still a matter of debate. Carlsson et al, demonstrated poor revascularization in transplanted islets, which could in-turn effect compromise the metabolic and insulin release by beta cells. This group observed mean pO2 in native pancreatic islets as ∼40 mmHg vs pO2 of ∼5 mmHg in revascularized islets irrespective of transplantation site. These studies suggest that revascularization is critical for islet transplant success, Poor revascularization are the key reasons of post-tx islet loss.

3. Strategies to improve the vascularization of the islet graft

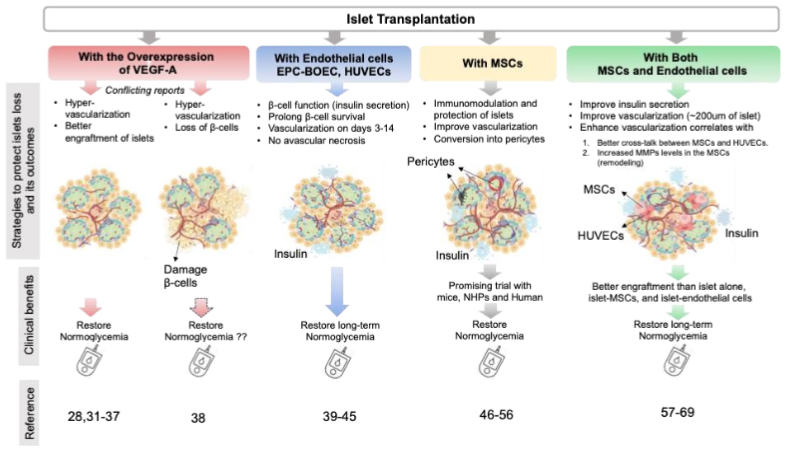

Poor revascularization in transplanted islets results in insufficient oxygen and nutrient supply, accumulation of waste, and worsening ischemia and hypoxia, ultimately leading to islet cell death and graft failure. This challenge has raised concerns about islet transplantation as a viable therapy for reversing T1D. Various strategies have been developed to enhance revascularization, including conjugating pro-angiogenic factors like VEGF and PDGF, inhibiting anti-angiogenic factors, implanting vascularization-promoting devices, and co-culturing or co-transplanting islets with blood-network-promoting cells such as mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and endothelial cells. These approaches aim to restore beta cell function in T1D patients by facilitating rapid and efficient revascularization of islet grafts.

3.1 OVER EXPRESSION OF VEGF FROM DONOR ISLETS

Though sequence of events orchestrating the re-vascularization are not known, pericellular proteolysis, sprouting or migration/proliferation of endothelial cells (EC), formation of new capillaries, and maturation of blood vessels are considered as few prime steps towards vascularization. In native pancreas, VEGF produced by crosstalk of endothelial and endocrine cells is responsible for the glomerular vasculature formation. Early and later stages of pancreas development require different extent of VEGF expression. Inactivation of VEGF-A (either in endocrine progenitors or differentiated β cells) is responsible for loss of intra-islet capillary density, vascular permeability and islet function. Interestingly, we have come across confounding studies on over expression of VEGF-A. Lammert and colleagues have reported that pancreas-wide overexpression of VEGF-A from early development to adulthood results in pancreatic hyper-vascularization, β cell mass expansion and islet hyperplasia. In this pursuit, Zhang et al., reported that transplantation of murine islets containing human VEGF165 cDNA (by adenoviral-mediated gene delivery system) in the kidney capsule of streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic mice were associated with restoring normoglycemia. These islets demonstrated augmented microvasculature and elevated insulin content. Furthermore, Brissova et al. reported that though increased VEGF-A production plays a pivotal role in β cell regeneration, transiently increased VEGF-A production in adult β cells increases the intra-islet endothelial cells activation but also β cell loss at the same time. Thus, these pieces evidence suggest VEGF-A expression is a double-edged sword in the process of islet vascularization, which needs to be fine-tuned in accordance with the microenvironment.

3.2. CO-TRANSPLANTATION OF ENDOTHELIAL CELLS IMPROVES VASCULARIZATION

Brissova et al., demonstrated that both donor and endothelial cells populations were involved in the process of post-tx revascularization. In-depth analysis of transplanted islets further revealed that some vessels were lined with donor endothelial cells, while others with recipient endothelial cells. They found no evidence of developing chimeric blood vessels in the human islet graft transplanted in the mouse. Multiple evidence also demonstrated the role of circulatory epithelial progenitor cells (EPC) in enhancing neovascularization in various clinical settings. Also, Mathews et al., demonstrated migration and homing EGFP+ bone marrow cells in the pancreas of mice injured with STZ. In this pursuit, the group in Korea co-transplanted 7,000 islet equivalents (IEQ) pig islets into the renal capsules of diabetic nude mice- with and without vascularization promoting human cord blood derived endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs; 5 × 105) isolated from umbilical cord blood obtained from normal births. Islet-EPC group, in this study, maintained normoglycemia (<200 mg/dL) on day 11, whereas the blood glucose in islet only group never restored normoglycemia. Also, mice transplanted with EPC demonstrated higher porcine insulin level (21.5 ± 2.0 ng/mL) under fasting as compared to the islet alone group (12.2 ± 2.6 ng/mL). Interestingly, the islet-EPC group revealed high vascular density from day 3 to day 14 as compared to the islet-only group. In a separate study, Coppens et al., co-transplanted 5 Human blood outgrowth endothelial cells (BOEC) with a different number of pig islets in kidney capsules to restore normoglycemia in severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice. Interestingly, this group demonstrated that mice transplanted marginal mass of islets i.e. 50 and 75 islets exhibited stable normoglycemia on day 7 post-tx. To evaluate the islet vascularization dynamics, i.v. injection of biotinylated Lycopersicon esculentum (LE) lectin was used 10 minutes before the animals were scarified and biotinylated LE was detected with streptavidin conjugated with Alexa-fluor-555. Till day 3 post-tx, lectin injection did not show any increase in functional blood vessels through islets but the mean vessel volume of co-transplanted islets (islets + blood outgrowth endothelial cells; BOEC) was doubled on day 28 post-tx. Importantly, they also observed a significant decrease in cell-death area in the islet+BOEC group on day 4 as compared to islet alone, thereby suggesting the role of BOEC in post-tx islet protection. This observation was further corroborated by Quaranta et al. This group showed the survival and function of marginal islets (700 IEq) upon co-transplantation with endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) (5×105 EPCs in the portal vein) in syngeneic rats. Therefore, co-transplantation of endothelial cells with islets, 1) protects islet beta cells, 2) decreases the need for islet mass to restore normoglycemia, 3) facilitates rapid and improved vascularization as compared to islet alone groups.

3.3. CO-TRANSPLANTATION OF MESENCHYMAL STROMAL CELLS ALSO GETTING ATTENTION

In addition to endothelial cells, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are adult progenitor cells and have been reported to play a major role in tissue repair. Tang et al., reported that transplantation of autologous MSCs decreased cardiomyocytes apoptosis, and concomitant increased blood vessel density and blood flow in a mice model of myocardial infarction. These observations were corroborated by Kim et al., in a separate study suggesting the inefficiency of endothelial cells to rescue cardiac functions in absence of bone marrow (BM) derived MSCs. However, the dose of MSCs to be used for angiogenesis is very important as at higher doses these cells are proven cytotoxic to endothelial cells. Furthermore, Figliuzzi et al., revealed the role of MSCs (1 × 106) in rescuing the hyperglycemia in diabetic Lewis rats transplanted with 2000 islets (never reverted hyperglycemia in islet alone group) in the kidney capsule. 2000 islets + MSCs group successfully helped to achieve good glucose control until nephrectomy. Vascular density for islet + MSCs was found remarkably higher than islet alone cases (1459 ± 66 capillaries/mm2 vs. 1002 ± 55 capillaries/mm2). In the same way, Itoh et al., also co-transplanted a marginal number of islets with MSCs to restore the hyperglycemia in the kidney capsule of LEW rats. Interestingly, all 8/8 recipients were able to restore normoglycemia with two-fold high density of vasculature on day 7. The study by Rackham et al., further reported that co-transplantation of MSCs with islets in kidney capsules takes less time to reverse normoglycemia than islet alone (7 days islet + MSCs vs. days islet alone). Interestingly, in immunohistochemistry islet + MSCs deciphered intact islet like architecture viz. endocrine area separated by extensive areas of non-endocrine tissue. Importantly, in addition to their role in re-vascularization, MSCs are good tools to embargo inflammation within and surrounding the non-endocrine tissue of the recipient after transplantation. In a study, Solari et al., transplanted marginal islet mass with MSCs in the omentum of a rat model. In addition to achieving normoglycemia, surprisingly, T- cells obtained from the recipients showed significantly less production IFN-γ and TNF-α upon ex-vivo activation. Also, the T cell population showed a significantly higher fraction of CD4+ IL-10+ subsets. Ben Nasr et al., systemically injected autologous and heterologous MSCs in allo-islet transplanted diabetic mice recipients and their data showed that allo-islet recipients treated with autologous MSCs from bone marrow showed Th2 skewing. However, even the systemic treatment of autologous MSCs could only delay the rejection process. In addition to mice model studies, the Norma S. Kenyon group performed allotransplantation of islets in non-human primates. They reported that MSC-islet co-transplantation in hepatic portal vein showed no difference in fasting C-peptide values between ones treated with delayed rapamycin and anti-CD154 and those that began treatment with rapamycin before allo-islet transplant. Grippingly, the graft destabilization is found to be linked with the decreased proportion of FoxP3+ T regs in the recipients, as more MSC infusion on graft dysfunction resulted in an increase in Tregs and also graft stabilization in terms of restoring fasting C-peptide levels.

4. Future perspectives

Though islet transplantation is the best suited treatment modality to reverse hypoglycemia, severing intra islet vasculatures, and vasculature inducing cells (islet endothelial cells) during the process of getting islet isolation is a real irony towards the successful engraftment, function, and survival of the transplanted islets. Co-transplantation of MSCs and endothelial cells turned out to be the unsurpassed remedy to deal with the problem of inducing neo-angiogenesis in the islets. By virtue of inducing self-condensation, MSCs help islets and endothelial cells to form a real islet-like entity that is proangiogenic and shown to induce intra-islet vasculature and therefore forms a conducive microenvironment for survival and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in the transplantation setting. Based on this, the islet-MSC-endo complex in a well-described ratio, will act as a NEO-ISLET to restore hyperglycemia in Type 1 diabetes patients. Similar to islets, MSCs and HUVECs derived from HLA-matched/mismatched individuals might elicit the mild immune response, that we have to test, whether we have to increase the doses of current immunosuppression regimen based on Edmonton protocol or not.

5. Conclusion

This review highlights the critical challenges and advancements in pancreatic islet transplantation for treating T1D. Despite the promising outcomes achieved through the Edmonton protocol and advancements in immunosuppressive regimens, the loss of islets due to poor vascularization remains a significant barrier. Co-transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and endothelial cells has emerged as a viable strategy to enhance revascularization, reduce hypoxia-induced islet loss, and improve long-term graft survival. These accessory cells not only support neo-angiogenesis but also provide immunomodulatory benefits, fostering a conducive microenvironment for islet engraftment. Emerging technologies, such as bioengineered neo-islets and prevascularized scaffolds, further strengthen the prospects of successful transplantation. However, addressing immune compatibility issues and ensuring the scalability of these approaches remain critical. As researchers continue to explore the integration of MSCs and endothelial cells, it is imperative to optimize their therapeutic ratios and delivery methods. In conclusion, advancing islet transplantation techniques, supported by innovative co-transplantation strategies, holds great promise for transforming the treatment landscape for T1D, improving patient outcomes, and addressing the global challenge of donor islet scarcity.

Conflict of Interest:

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement:

This research is supported in part by projects funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and foundation grants.

Acknowledgements:

The author(s) acknowledge the institutional resources and support that have facilitated this work. The authors also appreciate the contributions of collaborators and colleagues for their valuable insights and discussions.

Contributions:

RN, AS: Conceptualized and wrote the manuscript, and created the figure. MP, AB, and DD: Review the manuscript. RN and AS: Contributed equally.

References

[1]. J. W. Yoon, and H. S. Jun, “Autoimmune destruction of pancreatic beta cells,” American Journal of Therapeutics, vol. 12, no. 6.pp 580-591, 2005.

[2]. G. A. Gregory, T. I. G. Robinson, S. E. Linklater, et al., “Global incidence, prevalence, and mortality of type 1 diabetes in 2021 with projection to 2040: a modelling study,” Lancet Diabetes Endocrinology, vol. 10, no. 10, pp 2022 741-760. doi: 10.1016/S22 13-8587(22)00218-2. Epub 2022 Sep 13. Erratum in: Lancet Diabetes Endocrinology, Oct 7, 2022; PMID: 36113507.

[3]. J. A. Noble, and H. A. Erlich, “Genetics of type 1 diabetes,” Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine, vol. 2, pp 1–15, 2012.

[4]. A. K. Steck, and M. J. Rewers, “Genetics of type 1 diabetes,” Clinical Chemistry, vol. 57 pp 176–185, 2011.

[5]. J. Tuomilehto, “The emerging global epidemic of type 1 diabetes,” Current Diabetes Report, vol. 13 pp 795–804, 2013.

[6]. DIAMOND Project Group, Incidence and trends of childhood Type 1 diabetes worldwide 1990-1999, Diabetic Medicine, vol. 23, no. 8. pp 857–866, 2006.

[7]. P. E. Cryer, “Banting Lecture. Hypoglycemia: the limiting factor in the management of IDDM,” Diabetes, vol. 43, no. 11, pp 1378–1389, 1994.

[8]. A. M. Shapiro, J. R. Lakey, E. A. Ryan, et al., “Islet transplantation in seven patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus using a glucocorticoid-free immunosuppressive regimen,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 343, no. 4, pp 230-238, 2000.

[9]. A. M. Shapiro, C. Ricordi, B. J. Hering et al., “International trial of the Edmonton protocol for islet transplantation,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 355, no. 13, pp 1318-1330, 2006.

[10]. E. Oetjen, D. Baun, S. Beimesche, et al., “Inhibition of human insulin gene transcription by the immunosuppressive drugs cyclosporin A and tacrolimus in primary, mature islets of transgenic mice,” Molecular Pharmacology, vol. 63, pp 1289–1295, 2003.

[11]. I. Hernández-Fisac, J. Pizarro-Delgado, C. Calle, et al., “Tacrolimus-induced diabetes in rats courses with suppressed insulin gene expression in pancreatic islets,” American Journal of Transplantation, vol. 7, pp 2455–2462, 2007.

[12]. N. Rostambeigi, I.R. Lanza, P. P. Dzeja, et al., “Unique cellular and mitochondrial defects mediate FK506-induced islet β-cell dysfunction,” Transplantation, vol. 9, pp 615–623, 2011.

[13]. R. Nishimura, S. Nishioka, I. Fujisawa, et al., “Tacrolimus inhibits the revascularization of isolated pancreatic islets,” PLoS One, vol. 8, no. 4, e56799, 2013.

[14]. B. L. Gala-Lopez, A. R. Pepper, R. L. Pawlick, et al., “Antiaging Glycopeptide Protects Human Islets Against Tacrolimus-Related Injury and Facilitates Engraftment in Mice,” Diabetes, vol. 65, no. 2, pp 451-462, 2016.

[15]. D. J. van der Windt, R. Bottino, G. M. Kumar, et al., “Clinical islet xenotransplantation: how close are we?” Diabetes, vol. 61, no. 12, pp 3046-3055, 2012.

[16]. D. K. Cooper, B. Gollackner, and D. H. Sachs, “Will the pig solve the transplantation backlog?” Annual Review of Medicine, vol. 53, pp 133, 2002.

[17]. C. Ricordi, C. Socci, A. M. Davalli, et al., “Isolation of the elusive pig islet,” Surgery, vol. 107, pp 688–694, 1990.

[18]. B. Hering, and N. Walawalkar, “Pig-to-nonhuman primate islet xenotransplantation,” Transplantation Immunology, vol. 21, pp 81-86, 2009.

[19]. K. Cardona, G. S. Korbutt, Z. Milas, et al., “Long-term survival of neonatal porcine islets in nonhuman primates by targeting costimulation pathways,” Nature Medicine, vol. 12, no. 3, pp 304-306, 2006.

[20]. J. Denner, “Why was PERV not transmitted during preclinical and clinical xenotransplantation trials and after inoculation of animals?” Retrovirology, vol. 15, pp 28, 2018.

[21]. G. Mattsson, L. Jansson, and P. O. Carlsson, Decreased vascular density in mouse pancreatic islets after transplantation. Diabetes, vol. 51, pp 1362 –1366, 2002.

[22]. F. C. Brunicardi, J. Stagner, S. Bonner-Weir, et al., “Microcirculation of the islets of Langerhans,” Diabetes, vol. 45, pp 385 –392, 1996.

[23]. L. Jansson, “The regulation of pancreatic islet blood flow,” Diabetes Metabolism Reviews, vol.10, pp 407 –416,1994.

[24]. P.O. Carlsson, P. Liss, A. Andersson, and L. Jansson, “Measurements of oxygen tension in native and transplanted rat pancreatic islets,” Diabetes, vol. 47, pp 1027 –1032,1998.

[25]. P. O. Carlsson, F. Palm, A. Andersson, and P, Liss, “Chronically decreased oxygen tension in rat pancreatic islets transplanted under the kidney capsule,” Transplantation, vol. 69, pp 761 –766, 2000.

[26]. P. O. Carlsson, F. Palm, A. Andersson, and P. Liss, “Markedly decreased oxygen tension in transplanted rat pancreatic islets irrespective of the implantation site,” Diabetes, vol. 50, pp 489 –495, 2001.

[27]. A. Boker, L. Rothenberg, C. Hernandez et al., “Human islet transplantation: update,” World Journal of Surgery, vol. 25, pp 481 –486, 2001.

[28]. P. Vajkoczy, A. M. Olofsson, H. A. Lehr, et al., Histogenesis and ultrastructure of pancreatic islet graft microvasculature, Evidence for graft revascularization by endothelial cells of host origin,” American Journal Pathology, vol. 146, no. 6, pp 1397-1405, 1995.

[29]. J. O. Sandberg, B. Margulis, L. Jansson, R. Karlsten, and O. Korsgren, “Transplantation of fetal porcine pancreas to diabetic or normoglycemic nude mice. Evidence of a rapid engraftment process demonstrated by blood flow and heat shock protein 70 measurements,” Transplantation, vol. 59, no. 12, pp 1665-1669,1995.

[30]. A. M. Davalli, L, Scaglia, D. H. Zangen, J. Hollister, S. Bonner-Weir, and G. C. Weir, “Vulnerability of islets in the immediate posttransplantation period. Dynamic changes in structure and function,” Diabetes vol. 45, no. 9, pp 1161-1167, 1996.

[31]. E. M. Conway, D. Collen, and P. Carmeliet, “Molecular mechanisms of blood vessel growth,” Cardiovascular Research, vol. 49, pp 507 –521, 2001.

[32]. M. Brissova, A. Shostak, M. Shiota, et al., “Pancreatic islet production of vascular endothelial growth factor–a is essential for islet vascularization, revascularization, and function,” Diabetes, vol. 55, no. 11, pp 2974-2985, 2006.

[33]. E. Lammert, O. Cleaver, and D. Melton, “Induction of pancreatic differentiation by signals from blood vessels,” Science, vol. 294, no. 5542, pp 564-567, 2001.

[34]. Q. Cai, M. Brissova, R. B. Reinert, et al., Enhanced expression of VEGF-A in β cells increases endothelial cell number but impairs islet morphogenesis and β cell proliferation., Developmental Biology, vol. 367, pp 40–54, 2012.

[35]. J. Magenheim, O. Ilovich, A. Lazarus, et al., “Blood vessels restrain pancreas branching, differentiation and growth,” Development, vol. 138, pp 4743–4752, 2011.

[36]. F. W. Sand, A. Hörnblad, J. K. Johansson, et al., “Growth-limiting role of endothelial cells in endoderm development,” Developmental Biololgy, vol. 352, pp 267–277, 2011.

[37]. N. Zhang, A. Richter, J. Suriawinata, et al., “Elevated vascular endothelial growth factor production in islets improves islet graft vascularization,” Diabetes, vol. 53, no. 4, pp 963-970, 2004.

[38]. M. Brissova, K. Aamodt, P. Brahmachary, et al., Islet microenvironment, modulated by vascular endothelial growth factor-A signaling, promotes β cell regeneration,” Cell Metabolism, vol. 19, no. 3, pp 498-511, 2014.

[39]. M. Brissova, M. Fowler, P. Wiebe, et al., “Intraislet endothelial cells contribute to revascularization of transplanted pancreatic islets,” Diabetes, vol. 53, no. 5, pp 1318-1325, 2004.

[40]. T. Asahara, T. Murohara, A. Sullivan, et al., “Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis,” Science, vol. 275, no. 5302, pp 964-967,1997.

[41]. K. Naruse, Y. Hamada, E. and Nakashima, et al., “Therapeutic neovascularization using cord blood-derived endothelial progenitor cells for diabetic neuropathy,” Diabetes, vol. 54, no. 6, pp 1823-1828, 2005. Erratum in: Diabetes, vol. 55, no. 5, pp 1534, 2006.

[42]. V. Mathews, P. T. Hanson, E. Ford, J. Fujita, K. S. Polonsky, and T. A. “Graubert. Recruitment of bone marrow-derived endothelial cells to sites of pancreatic beta-cell injury,” Diabetes, vol. 53, no. 1, pp 91-98, 2004.

[43]. S. Kang, H. S. Park, A. Jo, et al., “Endothelial progenitor cell cotransplantation enhances islet engraftment by rapid revascularization,” Diabetes, vol. 61, no. 4, pp 866-876, 2012.

[44]. V. Coppens, Y. Heremans, G. Leuckx, et al., “Human blood outgrowth endothelial cells improve islet survival and function when co-transplanted in a mouse model of diabetes,” Diabetologia, vol. 56, no. 2, pp 382-390, 2013.

[45]. P. Quaranta, S. Antonini, S. Spiga, et al., “Co-transplantation of endothelial progenitor cells and pancreatic islets to induce long-lasting normoglycemia in streptozotocin-treated diabetic rats,” PLoS One, vol. 9, no. 4, e94783, 2014.

[46]. M. L. da Silva, P. C. Chagastelles, and N. B. Nardi, Mesenchymal stem cells reside in virtually all post-natal organs and tissues, Journal of Cell Science, vol. 119, pp 2204–2213, 2006.

[47]. Y. X. Xu, L. Chen, R. Wang et al., “Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for diabetes through paracrine mechanisms,” Medical Hypotheses, vol. 71, pp 390–393, 2008.

[48]. Y. L. Tang, Q. Zhao, Y. C. Zhang, et al., “Autologous mesenchymal stem cell transplantation induce VEGF and neovascularization in ischemic myocardium,” Regulatory Peptides, vol 117, pp 3-10, 2004).

[49]. E. J. Kim, R. K. Li, R. D. Weisel, et al., Angiogenesis by endothelial cell transplantation, The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, vol. 122, no. 5, pp 963–971, 2001.

[50]. M. Figliuzzi, R. Cornolti, N. Perico, et al. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells improve islet graft function in diabetic rats, Transplant Proceedings, vol. 41, no. 5, pp 1797-1800, 2009.

[51]. T. Ito, S. Itakura, I. Todorov, et al., “Mesenchymal stem cell and islet co-transplantation promotes graft revascularization and function,” Transplantation, vol. 89, no. 12, pp 1438-1445, 2010.

[52]. C. L. Rackham, P. C. Chagastelles, N. B. Nardi, et al., “Co-transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells maintains islet organisation and morphology in mice,” Diabetologia, vol. 54, no. 5, pp 1127-1135, 2011.

[53]. M.G. Solari, S. Srinivasan, I. Boumaza, et al., “Marginal mass islet transplantation with autologous mesenchymal stem cells promotes long-term islet allograft survival and sustained normoglycemia,” Journal of Autoimmunity, vol. 32, pp 116–124,2009.

[54]. M. Ben Nasr, A. Vergani, J. Avruch, et al., Co-transplantation of autologous MSCs delays islet allograft rejection and generates a local immuno-privileged site,” Acta Diabetologica, vol. 52, no. 5, pp 917-927, 2015.

[55]. D. M. Berman, M. A. Willman, D. Han, et al., “Mesenchymal stem cells enhance allogeneic islet engraftment in nonhuman primates,” Diabetes, vol. 59, no. 10, pp 2558-2568, 2010.

[56]. H. Wang, C. Strange, P.J. Nietert, et al., “Autologous Mesenchymal Stem Cell and Islet Cotransplantation: Safety and Efficacy,” Stem. Cells Translational Medicine, vol. 7, no. 1, pp 11-19, 2018.

[57]. K. Matsumoto, H. Yoshitomi, J. Rossant, and K. S. Zaret, “Liver organogenesis promoted by endothelial cells prior to vascular function,” Science, vol. 294, pp 559-563, 2001.

[58]. T. Takebe, K. Sekine, Y. Suzuki, et al., Self-organization of human hepatic organoid by recapitulating organogenesis in vitro. Transplant. Proc., 44 (2012)1018-1020.

[59]. T. Takebe, K. Sekine, M. Enomura, et al., “Vascularized and functional human liver from an iPSC-derived organ bud transplant,” Nature, vol. 499, pp 481-484, 2013.

[60]. T. Takebe, R .R. Zhang, H. Koike, et al., “Generation of a vascularized and functional human liver from an iPSC-derived organ bud transplant,” Nature Protocols, vol. 9 , pp 396-409, 2014.

[61]. U. Johansson, I. Rasmusson, S. P. Niclou, et al., “Formation of composite endothelial cell-mesenchymal stem cell islets: a novel approach to promote islet revascularization,” Diabetes, vol. 57, no. 9, pp 2393-2401, 2008.

[62]. C. M. Ghajar, K. S. Blevins, C. C. Hughes, S. C. George, and A. J. Putnam, “Mesenchymal stem cells enhance angiogenesis in mechanically viable prevascularized tissues via early matrix metalloproteinase upregulation,” Tissue Engineering, vol. 12, pp 2875 –2888, 2006.

[63]. M. Buitinga, K. Janeczek Portalska, D. J. Cornelissen, et al., “Coculturing Human Islets with Proangiogenic Support Cells to Improve Islet Revascularization at the Subcutaneous Transplantation Site,” Tissue Engineering Part A, vol. 22, no. 3-4, pp 375-385, 2016.

[64]. N. C. Rivron, E. J. Vrij, J. Rouwkema, et al., “Tissue deformation spatially modulates VEGF signaling and angiogenesis,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, vol. 109, no. 18, pp 6886-68891, 2012.

[65]. J. Hilderink, S. Spijker, F. Carlotti, et al., “Controlled aggregation of primary human pancreatic islet cells leads to glucose-responsive pseudoislets comparable to native islets,” Journal of cellular and molecular medicine, vol. 19, no. 8, pp 1836-1846, 2015.

[66]. L. da Silva Meirelles, A. M. Fontes, D. T. Covas, and A. I. Caplan, “Mechanisms involved in the therapeutic properties of mesenchymal stem cells,” Cytokine Growth Factor Reviews, vol. 20, no. (5-6), pp 419-427, 2009.

[67]. Q. Chen, M. Jin, F. Yang, J. Zhu, Q. Xiao, L. Zhang, “Matrix metalloproteinases: inflammatory regulators of cell behaviors in vascular formation and remodeling,” Mediators of Inflammation,” vol. 928315, 2013.

[68]. P. Carmeliet, “Mechanisms of angiogenesis and arteriogenesis,” Nature Medicine, vol. 6, no. 4, pp 389-395, 2000.

[69]. M .J.Cross, and L. Claesson-Welsh, FGF and VEGF function in angiogenesis: signalling pathways, biological responses and therapeutic inhibition,” Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, vol. 22, no. 4, pp 201-207,2001.

[70]. S. J. Grainger, B. Carrion, J. Ceccarelli, and A. J. Putnam, Stromal cell identity influences the in vivo functionality of engineered capillary networks formed by co-delivery of endothelial cells and stromal cells. Tissue Engineering, Part A, vol. 19, no. 9-10, pp 1209-1222, 2013.