Extracellular Vesicles Deliver p53 to Induce Cancer Apoptosis

Functional delivery of xenogeneic p53 via extracellular vesicles induces apoptosis in human cancer cells

Gil Shalev ¹, Bracha Shraibman ¹, Albina Lin ¹, Adam Masarwa ¹, Alla Savchuk ¹, Yevgeny Tendler ¹, Lana Volokh ¹, Alexander Tendler ¹

¹ AnserBio

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 July 2025

CITATION Shalev, G., Shraibman, B., et al., 2025. Functional delivery of xenogeneic p53 via extracellular vesicles induces apoptosis in human cancer cells. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(7). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i7.6725

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i7.6725

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

TP53 (encoding for the p53 tumor suppressor protein) is the most frequently mutated or deleted gene in human cancers, undermining p53’s critical role in regulating cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Here, we present a novel p53 replacement strategy using extracellular vesicles derived from chicken corneal epithelial cells, which naturally express high levels of cytoplasmic wild type p53. We demonstrate that corneal epithelium cells-derived extracellular vesicles encapsulate xenogeneic p53 and are readily internalized by human cancer cells, including those with mutant or null p53 backgrounds. Upon uptake, extracellular vesicles-delivered p53 translocates to the nucleus and activates canonical p53-dependent apoptotic pathways, evidenced by transcriptional upregulation of target genes such as p21, BAX, and PIDD, and induction of apoptosis across a range of human cancer cell lines. Proteomic and phosphoproteomic analyses of extracellular vesicles’ cargo revealed enrichment of apoptotic regulators and phosphorylated p53-associated proteins. In addition, p53-containing vesicles exhibited minimal cytotoxicity in primary human fibroblasts and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells, suggesting a selective anti-tumor activity. We also show that pre-treatment with chemotherapeutic agents sensitized cancer cells to vesicles-delivered p53, manifested by enhanced apoptosis. This study introduces an extracellular vesicles-based approach for functional p53 replacement, offering a promising therapeutic platform for targeting tumors with p53 loss or mutation.

Keywords:

Xenogeneic p53 protein, extracellular vesicles, apoptosis, cancer therapy.

Introduction

The p53 protein is essential for maintaining genomic stability and preventing tumor development by responding to cellular stress or DNA damage. Upon activation, p53 acts as a transcription factor, orchestrating multitude of cellular processes through now well characterized set of target genes. Most importantly, p53 halts the cell cycle to enable DNA repair or to initiate apoptosis (programmed cell death) under severe unrepairable DNA damage. Mutations in the TP53 gene disrupt these protective mechanisms, leading to unregulated cell division, accumulation of damaged DNA and progression from pre-cancerous lesions to malignant tumors. Moreover, mutated p53 may lose its tumor-suppressive action, and instead acquire oncogenic function promoting cancer progression. TP53 mutations appear in about half of all human cancers, frequently resulting in aggressive and therapy resistant cancers and adversely affecting clinical prognosis. Additionally, mutant p53 molecules might exert a dominant negative effect by inhibiting anti-cancer activity of heterologous p53 tetramers. Due to its central role in cancer, p53 has been seen as an attractive target for cancer therapy for several decades now. Clinical trials directed to cancer therapy explored numerous strategies involving p53 mechanism of action. These include wild-type (WT) p53 function restoration, targeting of mutant p53 molecules and innovating immune-therapeutics and vaccines. Nonetheless, it is broadly asserted that further strategies for p53-based therapies are critically needed.

Herein, we introduce a novel approach utilizing p53 containing extracellular vesicles (EVs) derived from chicken corneal epithelium cells (CCECs). Uniquely strong cytoplasmic expression of p53 in corneal epithelial cells has been previously described and further linked to an evolutionary function across various species. These elevated expression levels were hypothesized to result from evolutionary pressure providing a local p53-dependent anti-cancer defense mechanism in the cornea through substantial amounts of p53-containing vesicles combined with the absence of the ubiquitin ligase MDM2 in the corneal epithelial cells. It was hypothesized that these elevated p53 levels govern a local anti-cancer defense mechanism through secretion of p53-containing vesicles into intercellular space and their subsequent capture by neighboring cells.

EVs are small membrane-bound bodies which carry bioactive molecules such as proteins, RNA, and DNA fragments and encompass pleiotropic biological functions including participation in immune response, antigen presentation, intracellular communication and transfer of RNA and proteins between cells. The potential of EVs for cancer therapy as drug delivery vehicles has now been well recognized. Beyond its well-known role in regulating cell-intrinsic response to DNA damage, p53 also plays a crucial role in intercellular communication itself, particularly in mediating the radiation-induced bystander effect (RIBE). The bystander effect describes a phenomenon in which non-irradiated neighboring cells exhibit responses to DNA damage signals transmitted directly from irradiated cells. This effect has been linked to the secretion of EVs, including exosomes. P53 has been implicated in this process as a key regulator of exosome-mediated signaling. Ionizing radiation induces the release of exosomes that can modulate cell survival, apoptosis, and DNA damage responses in neighboring cells. The p53-dependent secretory pathway is central to this mechanism, shaping both the composition and function of exosomes released under stress. For example, in TSAP6/Steap3-null mice-where the p53-dependent pathway is disrupted-exosome secretion is severely compromised, resulting in diminished intercellular communication and an attenuated bystander effect. These findings highlight that p53 governs not only cell-autonomous stress responses but also the transmission of stress signals to surrounding cells via exosome-mediated pathways. Additionally, p53-regulated exosomal content has been found to include factors involved in immune responses and cell survival, further influencing the fate of bystander cells. The secretion of p53-containing vesicles may enhance protective mechanisms in surrounding cells, potentially contributing to a broader anti-cancer defense. This aligns with the hypothesis that corneal epithelial cells utilize p53-containing vesicles to create a local protective environment against oncogenic transformation.

Given the critical role of p53 in the bystander effect and its influence on intercellular signaling, further investigation into p53-mediated exosomal pathways may offer unique therapeutic opportunities, particularly in the context of cancer therapy. Following characterization of the vesicles and their mechanism of action, we present results supporting their therapeutic potential as monotherapy as well as in combination with currently used chemotherapy agents for colon cancer treatment.

Materials and Methods

Chicken corneal epithelium cells culturing and vesicles harvesting.

CCECs were grown as primary culture in DMEM. EVs were harvested when the culture reached ≈ 90% confluency, according to proprietary protocol.

Extracellular vesicles’ purification by tangential flow filtration (TFF)

Extracellular vesicles were purified using mPES 300 kDa hollow fiber filter (Repligen) to remove proteins and free biomolecules. The filter was first washed with three column volumes of sterile PBS (pH 7.4), then 0.1 M NaOH, and lastly, additional with three column volumes of PBS. The sample was then subjected to ultrafiltration in the TFF fiber. EVs were concentrated 3-fold and then analyzed.

Nanoparticle Tracking Analyses (NTA)

NTA were conducted by using the Envision V 2.1.12.0 NTA Particle Analyzer (HYPERION ANALYTICAL, United States), under no flow, and under instrument settings of 15% detection threshold, 7.0 msec of exposure, laser wavelength of 486 nm and a laser power of 9.9-10.1 milliwatts. Samples were assessed according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Three successive measurements were taken for each source material with 1000 particles scored in each analysis.

Mass spectrometry

Proteolysis: EV samples were brought to concentration of 5% Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS), 100 mM Tris pH=8 and 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). Samples were heated for 5 minutes at 95°C, further sonicated (x2) and subsequently precipitated in 80% acetone. Proteins pellets were washed 4 times with cold 80% acetone, and then resuspended in 8 Molar urea, 400 mM ammonium bicarbonate and 10 mM DTT. Proteins were reduced (60ºC for 30 minutes), with 40 mM iodoacetamide (room temperature for 30 minutes in the dark). 20 μg of proteins were then digested in 2 Molar Urea in the presence of 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate and a modified trypsin for 16 hours at 370C in a 1:50 mass-to-mass enzyme to-substrate ratio.

Mass spectrometry analysis: The tryptic peptides were desalted using C18 tips dried and resuspended in 0.1 % formic acid. One µg of the resulting peptides was analyzed by LC MS/MS using a Q-Exactive Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer (Thermo), fitted with a capillary HPLC (Dionex). Peptides were loaded onto a homemade capillary column (30 cm, 75-micron ID), packed with Reprosil C18-Aqua (Dr Maisch GmbH, Germany) in solvent-A (0.1% formic acid in water). Peptides were eluted at flow rates of 0.15 μl/min with 3 steps of an acetonitrile gradient with 0.1% formic acid in water: a linear 30 minutes of 5-28 %, 15 minutes gradient of 28-95% and 15 minutes at 95 % acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid in water. Mass spectrometry was performed in a positive mode using repetitively full MS scan (m/z 300–1800), followed by high energy collision dissociation of the 10 most dominant ions selected from the full MS scan. A dynamic exclusion list was enabled with exclusion duration of 20 seconds.

Data Analysis: Data was analyzed using MaxQuant 1.6.10.43 for identification and quantification against the Gallus gallus UniProt databases. Oxidation on methionine and acetylation on protein N-term were accepted as variable modifications and carbamidomethyl on cysteine was accepted as static modifications on the denatured samples. Minimal peptide length was set to 6 amino acids and a maximum of two mis-cleavages was allowed. Peptide- and protein-level false discovery rates (FDRs) were filtered to 1% using the target-decoy strategy. Protein tables were filtered to eliminate the identifications from the reverse database, and common contaminants and single peptide identifications. The data was quantified by using the same software (summed up extracted ion current of all isotopic clusters associated with the identified amino acid sequence). Additional statistical analysis was done by Perseus 1.6.15.0.

Enrichment for phosphorylated peptides: Extracellular vesicle samples were extracted, trypsinized and enriched for phosphorylated peptides using TiOX beads. Peptides eluted from the beads were analyzed by LC-MSMS using the Orbitrap Exploris™ 480 Mass Spectrometer. Outcomes of the mass spectrometer were analyzed by the Max quant software (v2.6.8.0) with 1% False Discovery Rate (FDR). In experiments of phospho-enrichment, peptides were also analyzed without enrichment for full proteomic analyses by LC-DIA MSMS, using the Exploris 480 Mass Spectrometer. The data was analyzed by DIANN software.

Cryo-Transmission Electron Microscopy (Cryo-TEM) sectioning:

The source for the cryo-sectioning protocol: generic negative staining protocol for initial visualization of the particles, followed by an immuno-staining step, for better-quality morphological micrographs. Towards the negative staining, grid preparation involved depositing 3 µl of EVs onto a TEM grid with a thin supporting film of carbon in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment. After removal of excess sample by blotting, a small amount of sample remained on the grid. The grid was then frozen by rapidly plunging in liquid ethane, i.e., the vitrification process, embedding the particles in the sample in an amorphous film of ice. The grid was subsequently stored in liquid nitrogen until it was inserted into the microscope for imaging. Cryo-TEM sectioning was employed following a negative staining with a Uranyl Acetate-containing buffer and following immuno-staining for p53 presence with an α-human p53 antibody (Ab) (GTX17698, GenTex) followed by a Gα-R secondary Ab conjugated to 12 nm-gold particles (AB_2338016, Jackson Immuno Research LABORATORIES INC).

Extracellular vesicles treatment and combination therapy

Cell lines.

The following human colon cancer cell lines were used: HCT116 p53 wild-type (WT) (ATCC, CCL-247), HCT116 p53 knockout (KO) (isogenic p53 null; ATCC, CRL-3449), HCT116 p53 WT tagged. HT29 (p53 R273H mutant) (ATCC, HTB-38), COLO320DM (p53 R248W mutant) (ATCC, CCL-220), LS123 (p53 R175H mutant) (ATCC, CCL-255), MC38 (murine colon carcinoma, p53 wild-type) (Applied Biological Materials, T8291). Non-colon human cancer lines included. Lung: H1299 (p53 null, homozygous deletion) (ATCC, CRL-5803), A549 (p53 wild-type) (ATCC, CCL-185). Glioblastoma (GBM): LN18 (p53 R273H mutant) (ATCC, CRL-2610), U87 (p53 WT) (ATCC, HTB-14), U118 (R213Q p53 mutant) (ATCC, HTB-15), LN229 (p53 WT) (ATCC, CRL-2611), LN308 (p53 null) (RRID: CVCL_0394). Ovarian cancer: SKOV-3 (p53 null, large deletion) (ATCC, HTB-77), CAOV-3 (p53 Y136 nonsense mutation, non-functional) (ATCC, HTB-75). Non-cancerous human fibroblast cells: CCD-18Co (colon-derived, p53 wild-type, immortalized) (ATCC, CRL-1459). GF3-GMP-Foreskin Fibroblast 3, p53 WT, (kindly provided by Accellta Ltd) and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells PBMCs.

All cell lines were cultured under standard conditions according to ATCC’s recommendations and treated with p53-containing EVs. The Annexin V-PI assay was conducted on EV-treated target malignant and non-malignant cells, aimed at assessing their potency on different cell types upon application. To that end, cell seeding was conducted onto 48 well plates (25,000 cells/well), and 0.5-12×109 particles/ml were applied for 24-48 hours of incubation. Subsequently, cells were harvested and further stained by the Annexin V-FITC (4700 Medical & Biological Laboratories CO., LTD.), in accordance with a protocol provided by the manufacturer. Outcomes of this staining were then analyzed by the NovoCyte Flow Cytometry system (Agilent, United States).

Additionally, human colon HT29, HCT116 p53 WT and HCT116 p53 KO cancer cell lines were pre-treated with 0.1-0.5 µM Irinotecan (818505, Sigma-Aldrich) for 4-8 hours prior to EV application. Cells were then co-incubated with Irinotecan + EVs for 24-48 hours (HCT116-24 hours, HT29-48 hours) followed by Annexin V-PI testing. The concentration of EVs for EVs-only treatment depended on cell line are: HCT116 KO 2×109 particles/ml, HCT116 WT 1.4×109 particles/ml, HT29 Mut 4×109 particles/ml.

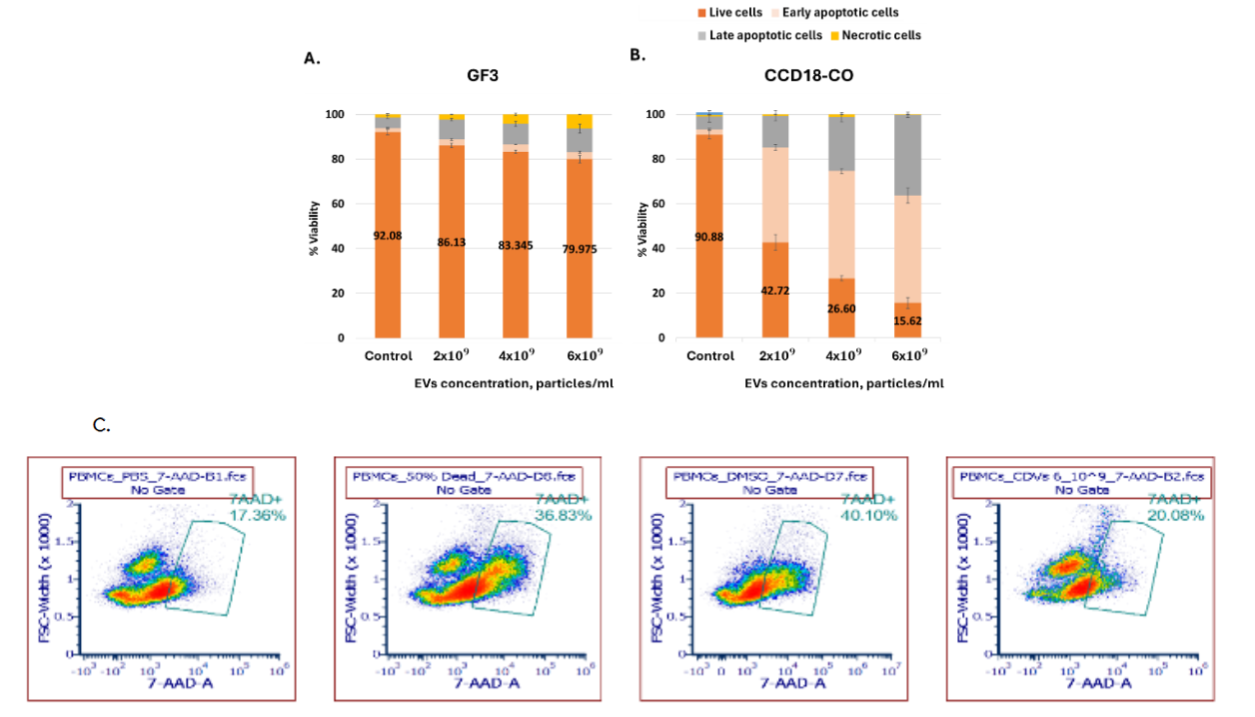

Evaluating apoptotic levels on human peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

To eliminate the possibility that the vesicles induce apoptosis in PBMCs, we conducted staining using the 7-AAD Viability Staining Solution (420403, Biolegend) and assessed the cells viability by flow cytometry. DMSO and heat shock served as positive controls, while PBS were used as negative controls. PBMCs were seeded in 96-well U-bottom plates at a density of 60,000 cells/well, and vesicles were applied at final concentrations ranging 1×107-1×109 particles/ml. After overnight incubation, cells were stained with the 7-AAD Viability Staining Solution and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Extracellular vesicles’ uptake assay.

HCT116 p53 KO cells were grown on coverslips within a six well plate up to 60% cell confluency in the presence complete growth medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. EVs at concentration of 3×1010 particles/ml were applied for 10 and 20 minutes at 37°C (300 µl/well). Cells were washed with PBS 3 times and were subsequently fixed by a 4.0 % Paraformaldehyde solution (SC-281692, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 10 minutes at 4°C. Following washes with 1xPBS (x3), slides were treated with 0.5% Triton x100 for 10 minutes at room temperature (RT) and were further blocked by a 5% BSA solution (in PBS) for 15 minutes at RT. Cells were then stained with the α-p53 Ab (2092R, Biotium at 1:200 or with customized PAb421 Ab) or saline containing 1% BSA within a PBS solution. These two anti-human p53 Abs were found to provide reliable staining of the chicken p53 protein in immuno-fluorescence studies, with a negligible basal level seen in HCT 116 KO p53 cells. Slides were then washed (PBS – x3) and stained with a Cy3-conjugated AffiniPure Goat α-Rabbit IgG F(ab’)2 Fragment Specific (111-165-047, Jackson), or Cy™3 AffiniPure® Goat Anti-Mouse IgG F(ab’)2 Fragment Specific (111-165-166) at 1:200 in the presence of 1% BSA in 1x PBS for 60 minutes, darkened, at RT. Cells were washed (1x PBS – x5) and were then stained with a Phalloidin-iFluor 647 Conjugate working solution (20555-300, Cayman Chemicals) for 30 minutes at RT. Following removal of the residual phalloidin conjugate (1x PBS-x3), slides were mounted with DAPI Fluoromount-G (0100-20, SouthernBiotech). Finally, a ‘Careline Color Nails’ was applied at the circumference of the slides to circumvent evaporation of the DAPI Fluoromount-G solution.

Image processing was performed by Python and MATLAB tools. At least 50 captured cells were analyzed, from which data processing libraries were constructed. Each image was analyzed in three separate channels for cytoplasm, nuclei and p53 staining. Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) methodology featuring local contrast enhancement was used for delimiting the cellular compartments. Cytoplasmic and nuclear segmentation were based on two independent pre-trained convolutional neural networks (CNN), providing the net distribution of p53 in each cellular compartment. Finally, area, signal strength and localization were exported as an excel sheet to generate distribution of the detected p53 protein between the two cellular compartments.

Direct staining of extracellular vesicles was conducted by seeding EVs on microscope slides, letting them dry for 15 minutes at RT. EVs were kept on a wet chamber, and where fixed by a pre-chilled 100% Methanol at -20°C for 30 minutes, and were directly subjected to staining with a primary Ab (Biotium 2092R at 1:500) for 1 hour at RT, followed by a Cy3-conjugated AffiniPure Goat α-Rabbit IgG F(ab’)2 Fragment Specific (111-165-047, Jackson) for 1 hour at RT. Upon washes, slides were mounted and observed by a fluorescent microscopy.

Analysis of RNA level of vesicles-treated cells.

Cells assayed by Real-Time PCR were primarily seeded in 6-well plate (BN30006, SPL); ≈ 1,000,000 cells within a final volume of 3 ml of complete growth medium, ≈ 16 hours prior to EV application. We employed a triple-EV dosing regimen, administering a dose of 5×1010 particles/ml, three times at 0, 30, and 60 minutes. Cells were then harvested for total RNA isolation at 90, 120, and 150 minutes after the initial EV application. The incentive for utilizing this EV application protocol was to point out the genes upregulated upon EV application under an intense stimulus. Measurements were hence encompassed time intervals (0-90, 0-120, and 0-150 minutes, respectively), during which genes could be upregulated and further monitored. Consequently, cells were washed with PBS, further spun at 2000 rpm for 5 minutes, and dry pellets were stored at -80°C until total RNA was isolated.

Total RNA isolations were conducted in accordance with the manufacturer protocol (036-25-M2 of A&A Biotechnology). RNA was eluted in 100 µl of DEPC-treated water, sample characteristics were explored by a Nanodrop 2000 device (Thermo Fisher scientific, United States), upon which samples were stored at -80°C. CDNA synthesis was conducted in accordance with the protocol provided (PB30.11-0.2 of PCRBIOSYST EMS) (500 ng of total RNA within a final volume of 30 µl). Real-Time PCR amplifications were performed with Forward and Reverse primers, bought as ‘Custom DNA Oligos’ from Sigma. The primers used are listed on the table below.

| # | Gene name | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HPRT | ATAAGCCAGACTTTGTTGG | ATAGGACTCCAGATGTTTCC |

| 2 | BAX | AACTGGACAGTAACATGGAG | TTGCTGGCAAAGTAGAAAAG |

| 3 | APAF1 | AAGCTCTCCAAATTGAAAGG | CCTTCTAAAAGGGAATGATCTC |

| 4 | FAS-AS1 | CCATCTGTAAAATGGGGATC | GATGGCTAATCAAAGAGACG |

| 5 | NOXA | GATGCCAGGTCCCTAATC | GACCTCTGTCTCTCTGCATC |

| 6 | PIDD | AGATATTCCCCAGTGGATG | TTTGAGGTGAAAGAAACAGTG |

| 7 | PML | AGAGGATGAAGTGCTACG | TACAGCTGCATCTTTCCC |

| 8 | YPEL3 | TTGGATCTCGTTTTTAACCC | ATGTACAAACGCTACAGAAC |

| 9 | GADD45A | GCTCAACGTAATCCACATTC | GAGATTAATCACTGGAACCC |

| 10 | p21 | TGGAGACTCTCAGGGTCGAAA | GGCGTTTGGAGTAGAAATC |

Primers were used at 400 nM within a final volume of 20 µl/reaction. Real-Time PCR amplification was conducted by the Corbett 5 Plex HRM model (Qiagen, United States). The protocol used consisted of the following steps:

- Hold at 95°C, 2 minutes.

- Cycling (40 repeats)

- Step 1: hold at 95°C, 10 seconds.

- Step 2: hold at 60°C, 30 seconds, acquiring Cycling A (Green).

Melting: Ramp from 57°C to 95°C. Hold for 90 sec on the 1st step. Hold for 5 seconds on the next steps, melt A (Green). Amplification analysis was conducted by Rotor-Gene Q Software 1.7.87. The delta-delta Ct method was utilized to calculate the relative fold gene expression of samples once compared to transcription levels of a normalizing gene (HPRT1), whose mRNA levels were evaluated simultaneously. The formula used was 2-∆∆Ct.

Analysis of protein levels of extracellular vesicles-treated cancer cells.

25,000 HCT116 tagged cells (HCT116 p53 WT-Venus(p53-VKI) + p21-CFP + PUMA-mCherry) were seeded in 48-well plates for 24 hr. Then, cells were treated with EVs in a concentration of 6×109 particles/ml. Lastly, cells were analyzed 6-24 hr. post treatment for their protein expression of p53-, p21- and PUMA-tagged cells using Cytek Aurora spectral flow cytometer. As reference, cells were treated with 20 µM Cisplatin which is known to induce upregulation of the tested genes followed by apoptosis.

Western blot analysis was performed following the lysis of protein samples by a 1X RIPA Buffer (AKR-190, Cell Biolabs, Inc), executed for 30 minutes at 4°C. Lysates were then spun for 15 minutes at 15,000 g, and supernatants were assessed for their protein content by the BCA kit (23225, Thermo Fisher scientific). Accordingly, 25 µg of total cell extracts were loaded on 4-20% gradient acrylamide gels (455-1093, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) and run under a constant voltage of 100 Volts in a vertical electrophoresis cell of Bio-Rad. Once analyzing exosomes, direct boiling of 25 µg proteins was conducted in the presence of 1x sample buffer (skipping the lysis step). A chicken custom-made α-p53 Ab (1:2,500) was used as primary antibody, and a GαR (IgG) secondary Ab pre-adsorbed AP was used at 1:2,000 (ab7091, Abcam). Note the commercial anti-human p53 Ab (2092R, Biotium) was found to be less efficient for detecting the chicken p53 protein in this protocol.

Results

The p53 protein is expressed in chicken corneal epithelial cells.

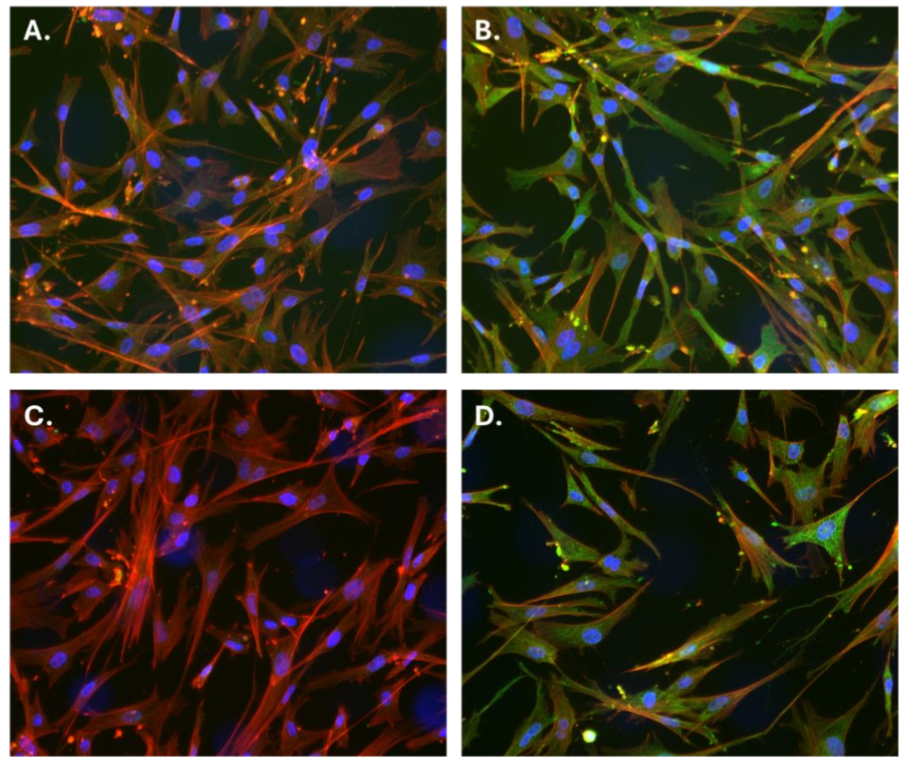

To assess the presence of p53 protein in CCEC, both immunofluorescence staining and western blot analyses were performed. Immunostaining using two different α-p53 antibodies: PAb 421 (Absolute) and 2092R (Biotium) revealed cytoplasmic localization of p53 in CCEC (Figure 1B, D, green), while control staining (lacking primary antibodies) showed no green fluorescence (Figure 1A, C). Cells were co-stained with DAPI (blue) and phalloidin (red) to visualize nuclei and cytoplasmic actin filaments, respectively. These results indicate the endogenous expression of p53 protein in the cytoplasmic compartment of CCEC.

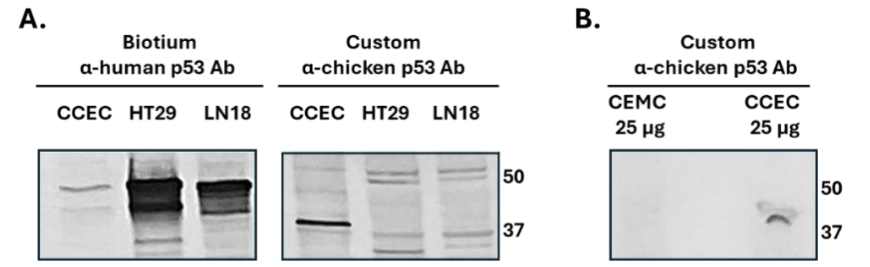

To validate these observations and confirm Ab specificity, western blotting was performed using the same Biotium α-human p53 Ab and a custom-made α-chicken p53 antibody. As shown in Figure 2A, while the α-human Ab barely identifies p53 at its expected molecular weight, the custom-made α-chicken Ab successfully detects a major band ranging 40 kDa in CCEC lysates, corresponding to the proper size of p53 (P10360 at Uniprot). Additional analysis (Figure 2B) demonstrated that the α-chicken Ab detected p53 in CCEC lysates and not in chicken embryonic muscle cells (CEMC), validating the Ab specificity and the expected expression of p53 in CCEC. Collectively, these results support the utility of CCEC as a source of p53-containing EVs.

Extracellular vesicles’ characterization: size distribution, morphology, and protein cargo

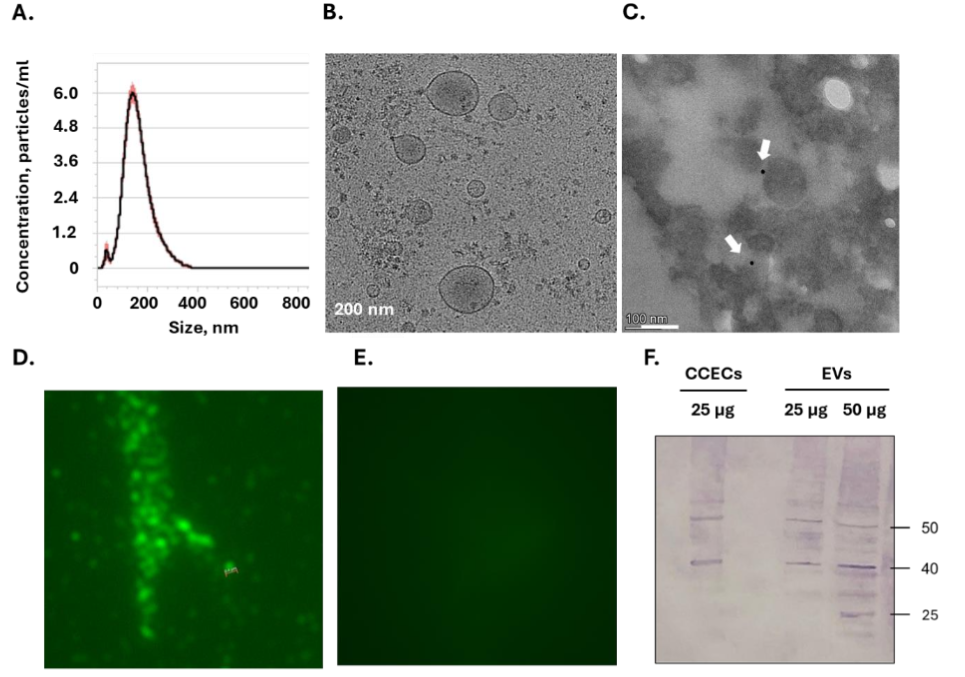

EVs isolated from CCEC were characterized by several methods. NTA indicated EVs ranging from 60 to 300 nm in size, with a mean diameter of ~160± 3 nm (Figure 3A). Cryo-TEM imaging indicated a typical round vesicular morphology (Figure 3B), and immunogold labeling confirmed the presence of p53 within the EVs (Figure 3C). Additional staining with an anti-chicken p53 Ab followed by Cy3-conjugated secondary Ab demonstrates a fluorescent signal in EVs (Figure 3D), while no signal is observed when staining is conducted in absence of primary Ab (Figure 3E). Western blot analysis indicates the presence of p53 in EVs under reduced conditions (Figure 3F). These findings confirm that CCEC-derived EVs encapsulate p53 and possess typical vesicular structure.

Proteomic analysis of EVs revealed a complex protein composition enriched for both pro-apoptotic and tumor-supportive signaling pathways. Functional enrichment analysis using g:Profiler identified statistically significant overrepresentation of biological processes related to apoptosis, cell death, and cellular stress response (adjusted p <0.005). Notable pro-apoptotic proteins detected in the EV cargo included BID, FADD, APAF1, and CASP3, all known mediators of extrinsic and intrinsic cell death pathways.

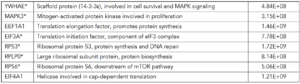

Additionally, several canonical tetraspanin markers-CD9, CD63, and CD81-were identified in the proteomic dataset, confirming the successful isolation of EV-enriched fractions and supporting their vesicular identity. The EV proteome was also significantly enriched for classical pro-survival pathways, including translation, cell cycle progression, and mitotic signaling. These were supported by high-abundance detection of ribosomal subunits (RPL, RPS), translation initiation and elongation factors (e.g., EIFs, EEF1A), and regulatory proteins such as YWHAE (14-3-3ε) and MAPK3. The “cell cycle” and “mitotic signaling” categories showed particularly strong statistical enrichment (adjusted p < 1e-7).

Importantly, while p53 peptides were not detected in the label-free proteomics dataset, a peptide encompassing phosphorylated Ser290 was detected with high confidence upon enrichment for phosphorylated peptides by TiOX beads. Alongside this, multiple proteins known to regulate or interact with the p53 signaling network were identified, including TP53BP1, TP53BP2, TP53RK, TP53I3, and PDRG1. Additional EV-resident components implicated in stress and death responses included CASP6, PCASP1, and TRAFD1.

| Protein | Function | Intensity |

|---|---|---|

| FADD | Adaptor for death receptor signaling (recruits caspase-8) | 1.38E+08 |

| BID | Bridges extrinsic to intrinsic apoptosis via tBID and BAX activation | 9.99E+07 |

| APAF1 | Forms apoptosome with cytochrome c and activates caspase-9 | 7.59E+07 |

| CASP3 | Executioner caspase cleaving structural and regulatory proteins | 4.58E+07 |

| TP53BP2 | Stabilizes p53, enhances transcription of apoptotic genes | 5.67E+08 |

| JMY | Transcriptional co-activator of p53, regulates apoptosis and cytoskeleton | 3.86E+07 |

| TP53BP1 | DNA damage sensor and mediator of p53 signaling | 3.92E+07 |

| TP53RK | Atypical kinase phosphorylating TP53, may assist in activation | 7.37E+06 |

| TP53I3 | p53-inducible gene involved in oxidative stress response | 7.71E+06 |

| PDRG1 | p53 and DNA damage-regulated protein | 9.44E+06 |

| WRAP53 | Stabilizes p53 mRNA, regulates DNA repair complexes | 2.89E+06 |

| BCLAF1 | Bcl-2-associated transcription factor, pro-apoptotic | 2.77E+07 |

| BCL2L13 | Pro-apoptotic mitochondrial Bcl-2 family member | 1.36E+07 |

| GADD45GIP1 | Stress-response modulator in GADD45A pathway | 1.51E+07 |

| CASP6 | Executioner caspase involved in apoptosis | 7.03E+06 |

| PCASP1 | Caspase-1-like protein, inflammation and cell death | 2.01E+06 |

| TRAFD1 | Regulates NF-κB and immune-apoptotic signaling | 1.20E+07 |

Table 1: Enrichment of apoptosis-related proteins in the extracellular vesicles’ proteome. List of pro-apoptotic and p53-associated proteins identified in the EV proteome, with their intensities and indication of statistical enrichment based on g:Profiler analysis (adjusted p<0.05). Proteins marked with an asterisk were part of statistically enriched functional categories in g:Profiler output (adjusted p < 0.05).

Table2: Enrichment of Tumor- Supportive Proteins in the Proteome of Extracellular Vesicles. List of canonical tumor-supportive proteins enriched in the EV proteome, along with their intensities and indication of statistical enrichment based on g:Profiler analysis (adjusted p<0.05). These include proteins involved in translation, mitotic progression, and MAPK signaling. * Proteins marked with an asterisk were part of statistically enriched functional categories in g:Profiler output (adjusted p < 0.05).

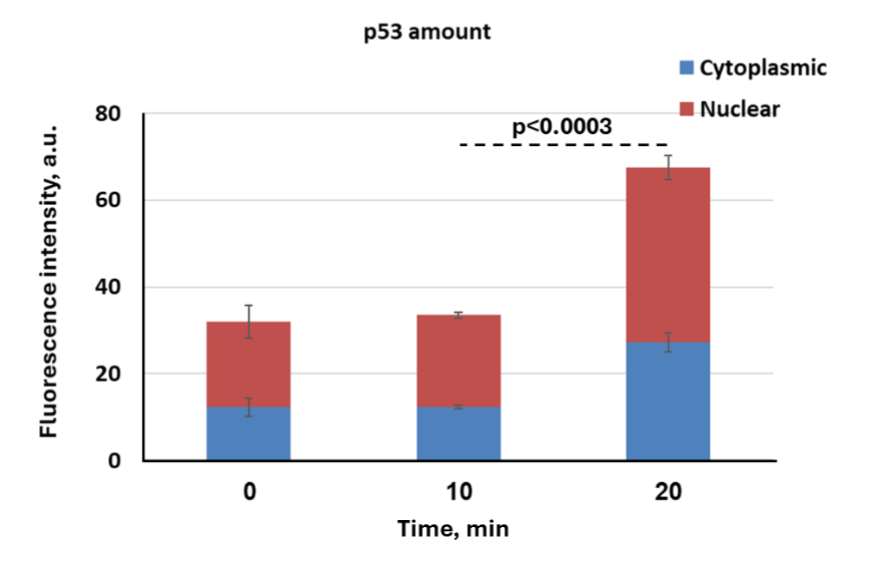

Nuclear Translocation of p53 Following Vesicles’ Uptake by Cancer Cells. To assess the functional delivery and nuclear translocation of p53 protein via EVs, we treated p53 KO HCT116 human colon carcinoma cells with p53-containing EVs derived from CCECs. Immunofluorescence analysis revealed internalization of EVs and localization of their cargo within recipient cells. Staining with Biotium α-human p53 Ab demonstrated cytoplasmic and nuclear punctate signals, indicating that the exogenous p53 protein was not only internalized but also targeted into the nuclear compartment of HCT116 cells. These findings support the efficient uptake of EV-delivered p53 and its nuclear targeting in p53-deficient cancer cells (Figure 4). Similar results were observed in SKOV-3 cells (data not shown), which carry a homozygous p53 mutation with minimal endogenous expression. There is a faint staining of the p53 protein detected before EV application (at time ‘0’ – baseline). Accordingly, p53 intensities were found to hold 31.9, 33.4 and 67.4 arbitrary units (AU) for baseline, and those treated for 10 and 20 minutes, respectively. This weak signal in at baseline could indicate residual expression of a non-functional p53 protein in HCT116 p53 KO cells, despite the implementation of CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing.

To quantify the intracellular distribution of EV-delivered p53 over time, we measured fluorescence intensity in the cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments of HCT116 p53 KO cells at 10- and 20-minutes upon EV application compared to baseline. As shown in Figure 5, p53 signal was barely detectable: change at 10 minutes compared to baseline. By 20 minutes, total p53-associated fluorescence increased significantly, with clear partitioning between cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments. Notably, more than half of the total signal was nuclear, supporting the rapid targeting of p53 into the nucleus 20 minutes upon application. This rapid targeting of p53 to the nuclei implies trafficking might be a facilitated process, allowing rapid and efficient nuclear localization.

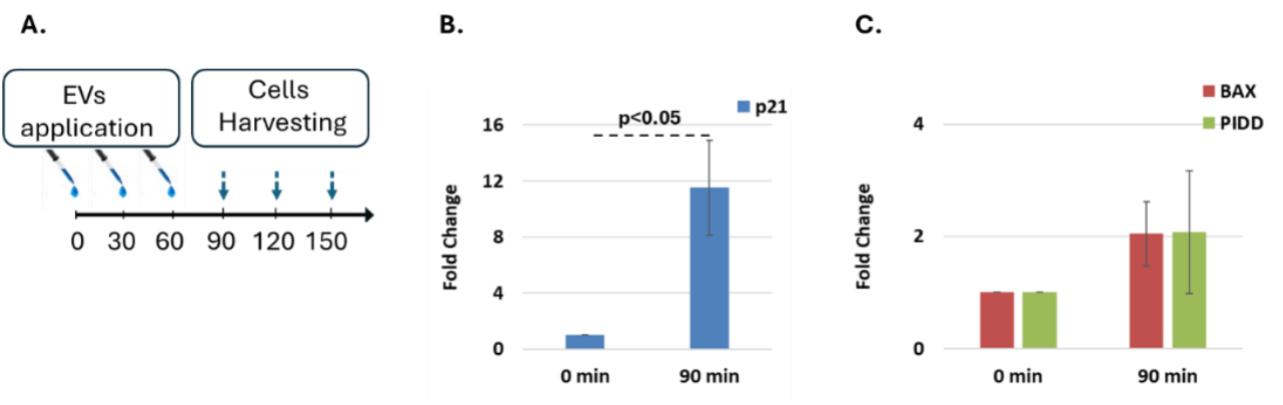

EV induce time- and dose-dependent transcriptional responses in HCT116 p53 knockout cells. Exogenous EV treatment of HCT116 p53 KO cells led to marked transcriptional activation of canonical p53 target genes. A strong upregulation of p21 was observed following high-dose EV delivery (5×1010 particles/ml, applied at 0, 30, and 60 minutes), reaching over 11-fold induction by 90 minutes. In contrast, BAX and PIDD exhibited only modest increases in expression, which did not reach statistical significance. Additional time points were assessed and showed upregulation in several genes, though the timing of peak induction varied across genes and experiments. Gene expression was normalized using HPRT1, which was mildly elevated throughout the experiment.

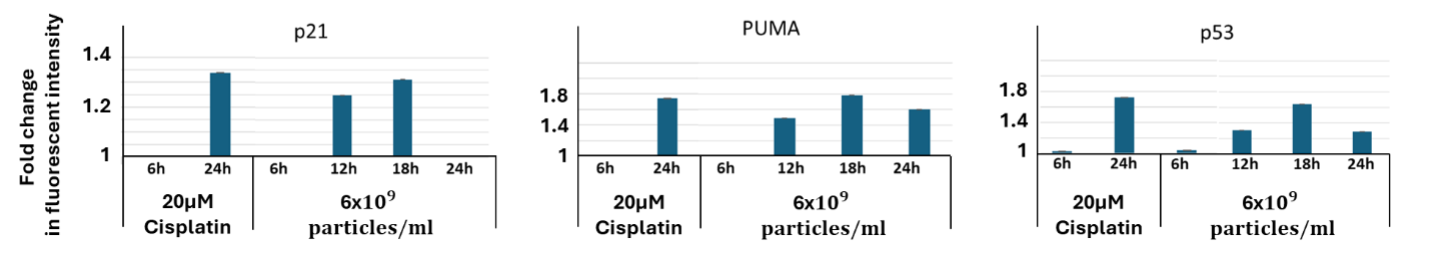

To evaluate downstream protein expression, HCT116 p53 WT-Venus (p53-VKI) reporter cells stably expressing p21-CFP and PUMA-mCherry were treated with EVs (6×109 particles/ml) and analyzed 6–24 hours post-treatment using spectral flow cytometry. p21 and PUMA proteins were strongly induced in a time-dependent manner, with increased expression detected from 12 hours onward and sustained through 24 hours. Interestingly, a modest but reproducible increase in p53 protein levels was also observed, particularly at later timepoints, suggesting possible post-translational stabilization or endogenous upregulation.

Anti-cancer activity assayed in-vitro.

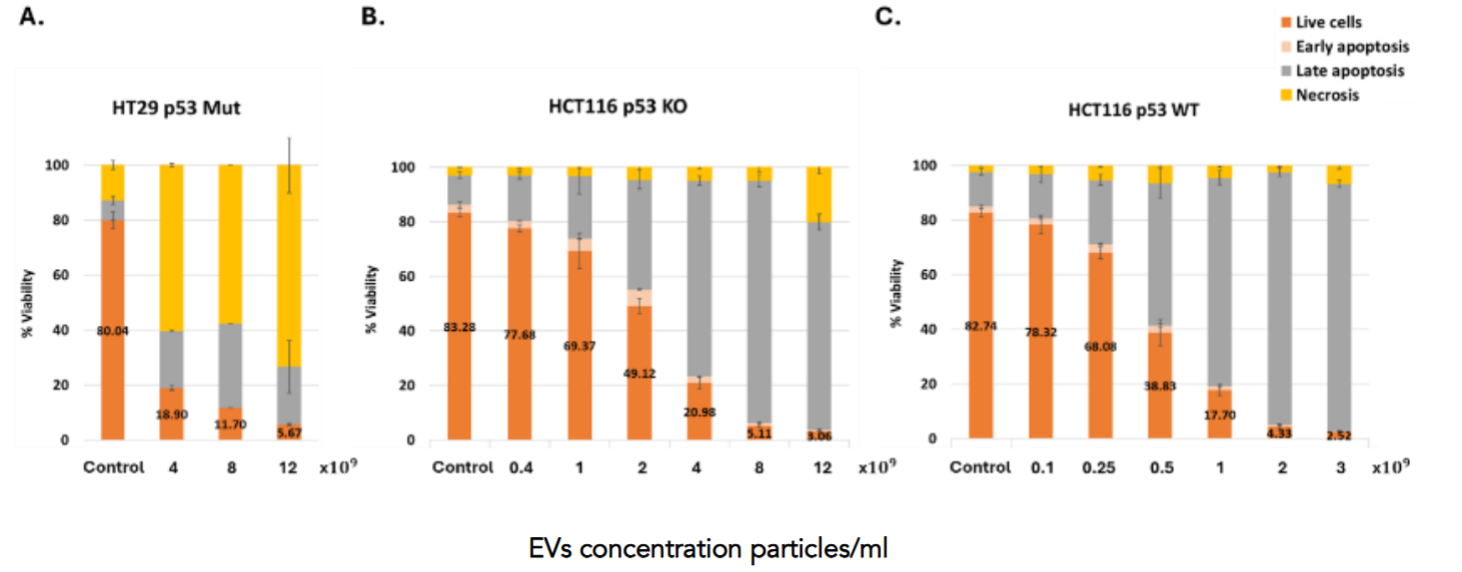

To evaluate the therapeutic potential of p53-containing EVs, we assessed their apoptotic effects on a panel of colon cancer cell lines carrying different status of the p53 protein (Human: HCT116 p53WT, HCT116 p53 KO, HT29 p53 Mut, Colo329 DM p53 Mut, LS123 p53 Mut, Murine: MC38 p53 Mut, (Figure 8) as well as non-cancerous cells (Figure 10). All colon cancer cells were treated with EVs in a concentration of 4×109 particles/ml, (except for LS123 that were treated with 8×109 particles/ml due to lower responsiveness), exhibited a significant reduction in viability, with increased early and late apoptosis and necrosis, compared to untreated controls. Additionally, other non-colon cancer cell lines — including lung cancer (H1299, p53 null; A549, p53 WT), GBM (U87, U118, LN18, LN229 and LN308), and ovarian cancer (SKOV-3 and CAOV-3) also responded to EV treatment with pronounced apoptosis (data not shown), underscoring the broad applicability and potent pro-apoptotic activity of p53-EVs across diverse tumor types. These findings support the potential of p53-EVs as a selective and effective cancer therapy.

Treatment with increasing doses of p53-containing EVs resulted in a dose-dependent reduction in cell viability across all tested colorectal cancer cell lines, with distinct response patterns depending on p53 status 24h after the treatment (Figure 9). In HT29 cells (p53 Mut), most of the cell death was attributed to necrosis, with only modest induction of apoptosis. In contrast, both HCT116 p53-KO and p53 WT cells displayed a pronounced apoptotic response. Notably, in HCT116 p53 WT cells, EV treatment induced a strong shift from viability to late apoptosis and necrosis, with over 60% of cells affected at the highest dose. A similar pattern was observed in HCT116 p53-KO cells, though the extent of apoptosis was slightly reduced. These results highlight the ability of EV-delivered p53 to trigger cell death even in the absence of endogenous p53 and suggest enhanced apoptotic sensitivity in the presence of functional p53.

Among non-cancerous control cells, GF3 primary fibroblasts showed minimal response (Figure 10A), while CCD-18Co fibroblasts exhibited a moderate apoptotic response (Figure 10B), suggesting partial sensitivity to p53-EVs. Flow cytometry analysis of PBMCs further confirmed low cytotoxicity on immune cells, with treated samples maintaining viability similar to controls (Figure 10C).

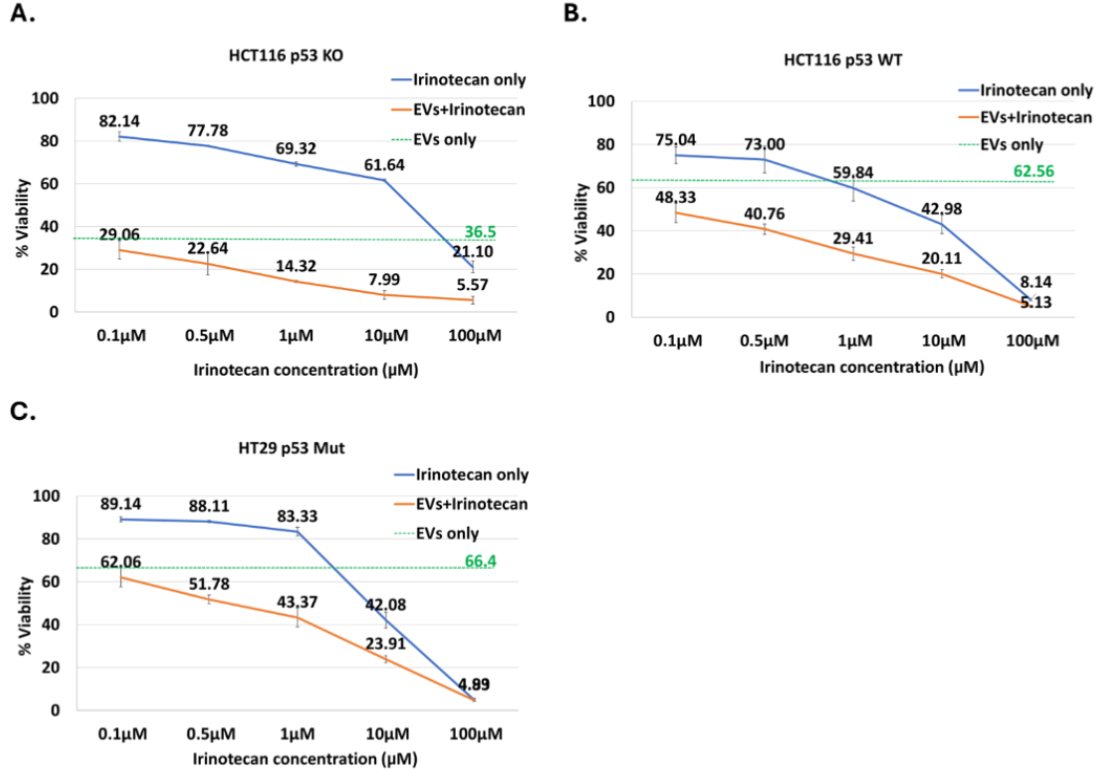

A synergistic pro-apoptotic effect of extracellular vesicles and chemotherapy

Multiple colon cancer cell lines were treated with p53-containing EVs in combination with standard-of-care chemotherapeutic agents commonly used in colon cancer therapy, including Irinotecan, Oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), and Cisplatin (only Irinotecan data is shown). Across different cell lines and agents, the combination of EVs with chemotherapy consistently resulted in a greater reduction in cell viability compared to either treatment alone, as assessed by Annexin V/PI assay. Representative data illustrates the observed synergistic effect of p53-containing EVs with irinotecan in HCT116 p53 KO, HCT116 p53 WT, and HT29 p53 Mut cells.

Discussion

This study presents compelling evidence that EVs derived from CCECs naturally enriched with WT p53 protein can robustly induce apoptosis in human cancer cells. Unlike strategies that attempt to restore or reactivate endogenous p53, our approach represents a p53 replacement therapy — delivering a xenogeneic p53 protein directly via vesicle transfer, and offering a gene-free, protein-based therapeutic alternative.

The efficacy of these p53-containing EVs as inducers of apoptosis was consistent across a wide panel of human cancer cell lines, including p53 WT, KO, and mutant backgrounds. Importantly, cells harboring well-characterized dominant-negative p53 mutations (e.g., HT29, Colo320DM, LS123) remained sensitive to treatment, suggesting that mutant human p53 does not interfere with the function of the exogenous chicken p53. This aligns with published data indicating limited or no cross-species tetramerization between chicken and human p53, allowing the xenogeneic protein to bypass dominant-negative suppression and function independently in the human cellular context.

Multiple lines of evidence support the delivery and intracellular activity of EV-contained p53. Cryo-TEM, fluorescence microscopy and western blotting confirmed the expected vesicular morphology and verified the presence of p53 protein within the EV lumen. Immunogold labeling and direct Ab staining showed specific p53 localization, while uptake assays demonstrated rapid internalization and nuclear translocation of p53 in target human cells within 20 minutes. Quantitative imaging and analysis confirmed time-dependent accumulation of p53 in both cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments.

The observed upregulation of p53 target genes, particularly the strong and consistent induction of p21, provides direct evidence that EV-delivered chicken p53 is transcriptionally active in recipient human cancer p53-KO cells. While other targets such as BAX and PIDD showed variable and statistically non-significant responses, their trends suggest partial engagement of the broader p53 pathway. Importantly, the induction of apoptosis observed in functional assays strongly supports the notion that additional pro-apoptotic p53 target genes were activated following EV treatment, even if their transcript levels were transient or not robustly captured at the tested time points. This functional outcome reinforces the interpretation that EV-delivered p53 initiates a complex, multi-gene response that includes—but is not limited to—p21 activation. The temporal pattern of gene induction varied between targets and time points. This variability likely reflects biological heterogeneity as well as the experimental design, where EVs were administered in three staggered doses (at 0, 30, and 60 minutes). This delivery approach introduces asynchronous uptake and signaling dynamics, making precise temporal interpretation challenging. Nonetheless, the detection of gene-specific upregulation confirms that EV-delivered chicken p53 protein is capable of reactivating its canonical transcriptional network in p53-KO cells, supporting the intended mechanism of action.

Further validation of p53 pathway reactivation was provided by protein-level data. In p53 WT reporter cells, EV treatment led to marked increases in p21 and PUMA proteins – canonical p53 targets. Interestingly, p53 protein levels were also elevated following treatment. While unexpected, this may reflect post-translational stabilization of endogenous p53 via EV cargo.

Supporting this hypothesis, mass spectrometry analysis of the EV proteome revealed the presence of phosphorylated p53 at Ser290, and several p53-associated modulators such as TP53BP2, TP53BP1, and TP53RK, which are known to enhance p53 stability or transcriptional activity. The EVs also carried central mediators of apoptotic signaling, including FADD, BID, APAF1, and CASP3, reinforcing their pro-death phenotype. Although biosynthetic and proliferative proteins were also detected, their impact appeared secondary to the dominant apoptotic signature. We propose that controlled stress induction during donor cell culture may further shift the EV cargo composition toward apoptosis-inducing components, enhancing therapeutic potency.

Notably, the anti-tumor effects of p53-EVs extended across a variety of tumor types, including colon, lung, glioblastoma, and ovarian cancer models. Importantly, the pro-apoptotic impact was selective: non-cancerous cells, including primary fibroblasts and PBMCs, showed minimal or only modest responses, suggesting a therapeutic window based on differential stress sensitivity or baseline p53 pathway status. In contrast, CCD-18Co fibroblasts (colon-derived, immortalized, p53 WT) exhibited a strong apoptotic response. This suggests that transformation-related cellular changes, such as immortalization, and aging of cells under culture conditions may also sensitize p53 reactivation due to accumulation of genetic instability such as chromosome rearrangements, leading to p53 dependent apoptosis.

In addition to monotherapy efficacy, our results reveal a synergistic interaction between p53-EVs, and conventional chemotherapeutic agents commonly used in colon cancer, including irinotecan, oxaliplatin, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). When chemotherapy was administered 4–7 hours prior to EV treatment, we observed a markedly enhanced apoptotic response compared to either agent alone. This sequence—where DNA damage induced by chemotherapy precedes p53 delivery—appears critical for maximizing synergy, likely by sensitizing tumor cells to p53-mediated apoptosis. In contrast, simultaneous addition of EVs and chemotherapy resulted in significantly lower levels of apoptosis, underscoring the mechanistic complementarity and the importance of precise temporal sequencing in combined treatment regimens.

Conclusion

Together, these findings support a therapeutic concept in which EVs serve as efficient vehicles for functional delivery of WT p53 protein. Rather than emphasizing the dual nature of the EV proteome, our results highlight a central, clinically relevant outcome: potent, targeted induction of apoptosis in human cancer cells. This approach may overcome the key limitations of existing p53-targeted strategies, including dominant-negative interference and delivery challenges, and offers a promising platform for combination of therapeutic regimens in otherwise resistant cancers.

Our current efforts are focused on optimizing the large-scale purification of EVs. In parallel, we plan to investigate the potential interaction between chicken p53 and human MDM2, an E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets p53 for degradation and prevents its accumulation. We hypothesize that human MDM2 exerts a weaker inhibitory effect on chicken p53 compared to its well-established impact on human p53, and we intend to explore this further. Furthermore, as the mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis pathway appears to play a role in this process, we aim to assess its contribution to EV-mediated, p53-dependent apoptosis.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to Maya Holdengreber, Melia Gurewitz, Lihi Shaulov and Raghd Abu-Sinni, members of the light microscopy, the electron microscopy and the image analysis Units of the Biomedical Core Facility of The Ruth and Bruce Rappaport Faculty of Medicine, at the Technion, Israel Institute of Technology, for their invaluable guidance and support throughout this study. We also wish to express our gratitude to The Smoler Proteomics Center at the Technion, Israel Institute of Technology. Special thanks to Prof. Tomer Cooks from The Shraga Segal Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Genetics of The Ben-Gurion University (Beer-Sheva, Israel), for continuous scientific consultancy and for providing necessary resources and facilities throughout this study. Special thanks to Prof. Galit Lahav from The Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, for in-depth scientific discussions.

Conflict of Interest Statement:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Statement:

None.

References:

- Wang, H., Guo, M., Wei, H. & Chen, Y. Targeting p53 pathways: mechanisms, structures and advances in therapy. Sig Transduct Target Ther 8, (2023).

- Zhang, C. et al. Gain-of-function mutant p53 in cancer progression and therapy. Journal of Molecular Cell Biology 12, 674–687 (2020).

- Roszkowska, K. A., Piecuch, A., Sady, M., Gajewski, Z. & Flis, S. Gain of Function (GOF) Mutant p53 in Cancer—Current Therapeutic Approaches. IJMS 23, 13287 (2022).

- Gencel-Augusto, J. & Lozano, G. p53 tetramerization: at the center of the dominant-negative effect of mutant p53. Genes Dev. 34, 1128–1146 (2020).

- Willis, A., Jung, E. J., Wakefield, T. & Chen, X. Mutant p53 exerts a dominant negative effect by preventing wild-type p53 from binding to the promoter of its target genes. Oncogene 23, 2330–2338 (2004).

- Patel, K. R. & Patel, H. D. p53: An Attractive Therapeutic Target for Cancer. CMC 27, 3706–3734 (2020).

- Wang, H., Guo, M., Wei, H. & Chen, Y. Targeting p53 pathways: mechanisms, structures and advances in therapy. Sig Transduct Target Ther 8, 92 (2023).

- Hong, B., Heuvel, A., Prabhu, V., Zhang, S. & El-Deiry, W. Targeting Tumor Suppressor p53 for Cancer Therapy: Strategies, Challenges and Opportunities. CDT 15, 80–89 (2014).

- Restoration of Wild‐Type p53 Function in Human Tumors: Strategies for Efficient Cancer Therapy. in Advances in Cancer Research 321–338 (Elsevier, 2007). doi:10.1016/s0065-230x(06)97014-6.

- Hassin, O. & Oren, M. Drugging p53 in cancer: one protein, many targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov 22, 127–144 (2023).

- Saxena, M., Van Der Burg, S. H., Melief, C. J. M. & Bhardwaj, N. Therapeutic cancer vaccines. Nat Rev Cancer 21, 360–378 (2021).

- Yang, Z., Sun, J. K.-L., Lee, M. M. & Chan, M. Restoration of p53 activity via intracellular protein delivery sensitizes triple negative breast cancer to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer 10, e005068 (2022).

- Hu, J. et al. Targeting mutant p53 for cancer therapy: direct and indirect strategies. J Hematol Oncol 14, 157 (2021).

- Peng, Y., Bai, J., Li, W., Su, Z. & Cheng, X. Advancements in p53-Based Anti-Tumor Gene Therapy Research. Molecules 29, 5315 (2024).

- Tendler, Y., Panshin, A., Weisinger, G. & Zinder, O. Identification of cytoplasmic p53 protein in corneal epithelium of vertebrates. Experimental Eye Research 82, 674–681 (2006).

- Tendler, Y. & Panshin, A. Features of p53 protein distribution in the corneal epithelium and corneal tear film. Sci Rep 10, (2020).

- Herrmann, I. K., Wood, M. J. A. & Fuhrmann, G. Extracellular vesicles as a next-generation drug delivery platform. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 748–759 (2021).

- Daguenet, E. et al. Radiation-induced bystander and abscopal effects: important lessons from preclinical models. Br J Cancer 123, 339–348 (2020).

- Pavlakis, E., Neumann, M. & Stiewe, T. Extracellular Vesicles: Messengers of p53 in Tumor–Stroma Communication and Cancer Metastasis. IJMS 21, 9648 (2020).

- Daguenet, E. et al. Radiation-induced bystander and abscopal effects: important lessons from preclinical models. Br J Cancer 123, 339–348 (2020).

- Lespagnol, A. et al. Exosome secretion, including the DNA damage-induced p53-dependent secretory pathway, is severely compromised in TSAP6/Steap 3-null mice. Cell Death Differ 15, 1723–1733 (2008).

- Watanabe, M., Hathcock, K., Vacchio, M., Moon, K. & Hodes, R. The role of p53 in antigen-specific and bystander T cell proliferative responses (50.15). The Journal of Immunology 184, 50.15-50.15 (2010).

- Wang, R., Zhou, T., Liu, W. & Zuo, L. Molecular mechanism of bystander effects and related abscopal/cohort effects in cancer therapy. Oncotarget 9, 18637–18647 (2018).

- Kim, C.-W. et al. Immortalization of human corneal epithelial cells using simian virus 40 large T antigen and cell characterization. Journal of Pharmacological and Toxicological Methods 78, 52–57 (2016).

- Tchounwou, P. B., Dasari, S., Noubissi, F. K., Ray, P. & Kumar, S. Advances in Our Understanding of the Molecular Mechanisms of Action of Cisplatin in Cancer Therapy. JEP Volume 13, 303–328 (2021).

- Paek, A. L., Liu, J. C., Loewer, A., Forrester, W. C. & Lahav, G. Cell-to-Cell Variation in p53 Dynamics Leads to Fractional Killing. Cell 165, 631–642 (2016).