Flipped vs. Traditional Classroom in Podiatric Education

The Flipped Classroom vs. the Traditional Classroom in Podiatric Medical Training: A Literature Review

Matthew Bernstein DPM ¹, DABPM, Jeffrey Ng DPM ²

¹New York College of Podiatric Medicine at Touro University.

² Metropolitan Hospital/Touro University.

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 June 2025

CITATION Bernstein, M., and Ng, J., 2025. The Flipped Classroom vs. the Traditional Classroom in Podiatric Medical Training: A Literature Review. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(6). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i6.6450

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i6.6450

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

Context: The traditional classroom emphasizes passive learning by a student lectured to by a professor, while the flipped classroom inverts this methodology, requiring students do most of the learning at home and then applying what they learn in interactive classroom sessions. As medicine evolves and technology changes, education methods must change as well. The purpose of this literature review is to analyze the benefits of the flipped classroom versus the traditional classroom in Podiatric and Medical student education.

Methods: To address the topic of the flipped classroom versus the traditional classroom in Podiatric Medical education, a comprehensive search was conducted through PubMed using the keywords ‘flipped classroom’ and ‘medical education’. The search was limited to articles written between 2020 and 2025 yielding 525 initial hits, which were screened based on title and abstract. The inclusion criteria were articles written in the previously stated timeframe, articles published in English, and articles specifically discussing medical education. An additional search was conducted through Google Scholar utilizing the same keywords, inclusion and exclusion criteria. Exclusion criteria were articles that either did not directly compare the flipped classroom to the traditional classroom, or there was no quantifiable data within the articles to support the metrics. Thus, fifteen articles were utilized in this literature review. The articles were organized thematically, and data was extracted using a standardized form. A narrative synthesis was used to synthesize findings.

Results: 15 reviewed articles directly compared the flipped classroom to the traditional classroom, with nine of these articles demonstrating statistically significant increases in student performance with the flipped classroom. Nine out of these 15 articles also demonstrated increased student satisfaction with the flipped classroom as opposed to the traditional classroom.

Conclusions: Based on this literature review, the flipped classroom approach can yield increased medical student performance as well as increased student satisfaction in the classroom as compared to the traditional classroom approach. As medicine evolves and technology changes, the flipped classroom approach appears to be beneficial in improving critical thinking and problem solving in medical school students.

Keywords

flipped classroom, traditional classroom, medical education

Introduction

Podiatric Medicine is a specialized field of Medicine in which the Physicians deal specifically with pathology of the foot, ankle, and lower leg. While there are 11 individual Colleges of Podiatric Medicine in the United States which educate students independently of our Allopathic and Osteopathic colleagues, the structure of Podiatric Education closely resembles that of Colleges of Allopathic and Osteopathic Medicine. The Selden Report in 1961 promoted major qualitative improvements in Podiatric Medical School which were accomplished through an increase and strengthening of full-time faculty, establishment of laboratories and library resources, and implementation of more rigorous admission standards. This helped Podiatric Medical schools mirror Allopathic and Osteopathic Medical schools in terms of curriculum and rigor. The first two years of Podiatric Medical education are spent entirely in the classroom, focusing on pre-clinical subjects; while the final two years are spent focusing on clinical medicine and clinical rotations. As is the case with all medical education, the goal of applying a mixture of didactic and clinical education is to produce competent and skilled Podiatric Physicians who are proficient in utilizing evidence-based medicine. Evidence-based medicine is required to enrich the clinical profession and enhance understanding of patient situations. Integrating evidence-based medicine into teaching requires comprehensive improvement in students’ cognition, attitude and behavior.

An excellent doctor must have enough self-learning ability and cooperation ability to keep up with the rapid development of medicine and master more advanced theories and techniques. Unfortunately, the amount of information in medicine continues to grow significantly, and the retention of basic science knowledge in medical school is often lost within a few years. Many medical students engage in mechanical memorization and study solely to pass exams. This hinders their deep understanding of knowledge and the development of all-around abilities. For hundreds of years, medical content has been delivered in a mostly traditional style, with an instructor lecturing and a learner passively taking in the information, to then be reviewed later when the exams approach. Traditional classrooms are resource-friendly and can convey information to a sizable audience; however, previous studies have shown that the receptivity of students in lecture begins to decline after 10 minutes, with lapses of inattentiveness occurring between 10 to 18 minutes. This passive one-way flow of information can leave students disinterested, bored, and prone to labeling the lecture material as irrelevant to medical practice. This passive learning method also takes time away from challenging student thinking, guiding them to solve practical problems, and encouraging direct application of material through active learning with instructors. This problem is further intensified by the growing needs of modern world students who are born and brought up in the digital era and therefore find the traditional lecture class very boring.

Teaching methodology should aim at reaching all students, and hence, should provide them with a good mix of visual, auditory, and kinesthetic situations to learn. Only students who are good at learning through the auditory method benefit from the traditional classroom method. Thus, instituting teaching methodologies that can assure additional active engagement of the students as well as the teachers is vital to making classrooms more interesting, enjoyable and useful.

Instructional methods that encourage interactive learning and applied clinical reasoning, such as the flipped classroom, are increasingly favored over classic lecture-based methods. A flipped classroom inverts the typical cycle of content acquisition and application, exchanging class time and conventional homework time. In this model, students prepare for class by reading and/or watching pre-recorded content, and then class time is devoted to applying this new knowledge through interactive activities.

This learner-centric model enables the educator to provide activities in the classroom that are action-based, authentic, connected, collaborative, innovative, high-level engagement, experience-based, project-based, inquiry-based, and self-actualizing. As an instructional teaching method, the flipped classroom has many advantages for both teachers and students. Students can learn at their own pace, build concepts with peers, feel less anxiety, receive instant feedback, and improve their confidence. Evidence suggests that flipped classrooms caused apparent improvement in students’ learning and performance and previous research has been conducted on the benefits of the flipped classroom versus the traditional classroom. For example, a systematic review of 118 research studies showed subjectively positive perceptions of flipped classrooms from students, while a different study analyzing the performance of fourth year medical students demonstrated that students in a flipped classroom performed significantly higher than their traditionally taught peers. While this short-term performance in the classroom and retention of knowledge is important; it is also important to develop and enhance students’ lifelong learning skills, clinical problem solving, and the ability to acquire new knowledge. The flipped classroom can potentially help students develop these skills by promoting the application of medical science knowledge and stimulating critical thinking.

The success of the flipped classroom model has been shown to be dependent on the self-regulation skills of its participants, as without these skills, students can fail to comprehend learning materials and/or to strategically utilize learning resources before class. In turn, they are less likely to follow and benefit from class activities. At the New York College of Podiatric Medicine, both methodologies of teaching are utilized. First- and second-year students are taught utilizing a traditional classroom model, while third year clinical students are taught utilizing a flipped classroom model. The courses in the third year are more specific to the practice of Podiatric Medicine itself, and it has been shown that course content relevant to core specialties and useful for future practice could facilitate increased knowledge acquisition retention within a constrained teaching time. Hence, the goal of our institution’s utilization of the flipped classroom in the clinical years is to enhance student understanding, interest, application and clinical skill in the subject matter specific to our specialty. The purpose of this research article is, therefore, to review the relevant data to compare the possible benefits of the flipped classroom versus the traditional classroom in medical education in terms of student satisfaction, overall success, and limitations of each teaching method.

Methods:

To address the topic of the flipped classroom versus the traditional classroom in Podiatric Medical education, a comprehensive search was conducted through PubMed using the keywords ‘flipped classroom’ and ‘medical education’. The search was limited to articles written between 2020 and 2025 yielding 525 initial hits, which were screened based on title and abstract. The inclusion criteria were articles written in the previously stated timeframe, articles published in English, and articles specifically discussing medical education. Exclusion criteria were articles that did not directly compare the flipped classroom to the traditional classroom, or there was no quantifiable data within the articles to support the metrics. An additional search was conducted through Google Scholar utilizing the same keywords, inclusion and exclusion criteria. Thus, fifteen articles were utilized in this literature review. The articles were organized thematically, and data was extracted using a standardized form. A narrative synthesis was used to synthesize findings.

Results:

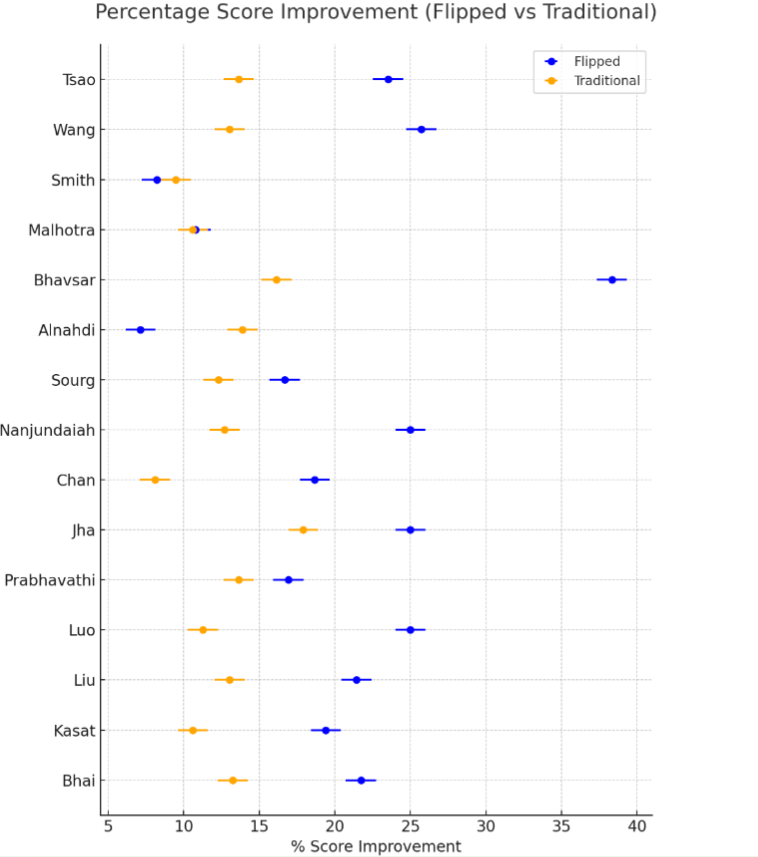

15 articles were reviewed which discussed the use of the flipped classroom versus the traditional classroom in medical education. A forest plot was constructed to illustrate the relative percentage improvement in pre- to post-test scores for each group. The majority of studies demonstrated greater gains in the flipped classroom cohorts.

Specifically, 13 out of 15 studies showed a higher percentage improvement in student performance with the flipped classroom. The mean relative improvement in the flipped group ranged from 7.1% to 38.3%, while traditional classroom improvements ranged from 8.1% to 17.9%. The most pronounced difference was seen in Bhavsar et al., where flipped classroom students improved by 38.3% compared to 16.1% in the traditional group.

These results visually support the conclusion that the flipped classroom model is associated with enhanced student performance outcomes, particularly in pre-clinical and clinical knowledge assessments. The Forest plot as a visual summary in Table 1 highlights the consistency and magnitude of these improvements across diverse educational settings and study designs.

Of those 15 articles, listed below are the highlights on student performance upon contrast and comparison:

- 9 studies demonstrated an increase in exam scores and overall student performance in the flipped classroom groups versus the traditional classroom groups.

- 1 study showed greater improvement in the flipped classroom group, without statistical significance.

- 2 studies demonstrated no statistically significant difference between the groups.

Additionally, 2 studies evaluated performance using non-exam metrics compared to the rest:

- one demonstrated an increase in the short-term and long-term retention of information in the flipped classroom group.

- Another demonstrated an increase in deep learning with a partially flipped format.

In addition to exam scores and student performance, student satisfaction outcomes were also reported and analyzed in the process of this literature review:

- 9 articles demonstrated increased student satisfaction and engagement with the flipped classroom.

- 1 study found no difference in student satisfaction between the two groups.

- None of these studies favored the traditional classroom.

Table 2: Summary of Articles in this Literature review.

| Authors | Study Participants and Design | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Tsao et. al | Ninety fifth-year medical students were enrolled and assigned to either experimental (flipped classroom) or control group (traditional classroom). Students in each group were given a “pre-test” and then “post-test”. “Post-Test” included written and oral test. | Compared with traditional teaching methods, the flipped classroom demonstrated better outcomes for both written and oral “post-tests”. These results were statistically significant. |

| Wang et. al | 138 fourth-year Orthopedic Students from Qilu Hospital were randomly assigned into traditional versus flipped classroom group from June 2022 to June 2023. At the end of internship year, students in each group were assessed on Orthopedic theoretical knowledge and practical operations. | Compared to the traditional classroom group, the flipped classroom group showed a statistically significant improvement in skill assessment scores. Additionally, the flipped classroom group also demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in overall student satisfaction rates as well as compared to the traditional classroom group. |

| Smith et. al | 47 Students in 2017 Emergency Medicine class were taught using traditional classroom method, while 46 students in 2018 Emergency Medicine class were taught utilizing flipped classroom method. Overall student performance and satisfaction rates were assessed for each group. | Students scored slightly lower on assessments in the flipped classroom versus the traditional classroom. However, student satisfaction score was slightly higher in the flipped classroom group. Neither result was significant. |

| Malhotra et. al | 95 First-year medical students were divided into two groups: flipped classroom and traditional classroom. A written test was conducted at the end of the period. At the conclusion of the period, the groups were reversed and the same procedure repeated. Student performance and overall satisfaction were assessed for each period. | There was no statistically significant difference in student performance between the two groups. However, 80% of the students preferred the flipped classroom. |

| Bhasavar et. al | 100 First-year medical students were divided into two groups: flipped classroom and traditional classroom. A written test was conducted at the end of the period. At the conclusion of the period, the groups were reversed and the same procedure repeated. Student performance and overall satisfaction were assessed for each period. | Students in the flipped classroom groups scored higher on post-tests as compared to traditional classroom. These results were statistically significant. Additionally, there was overall positive feedback for the flipped classroom as compared to the traditional classroom. |

| Alnahdi et. al | 132 third-year medical students were divided into traditional versus flipped classroom during a Neurosciences course block. Results were obtained utilizing a post-test, a questionnaire and semi-structured interviews. | The performance of students was better in the traditional classroom as compared to the flipped classroom. This result was statistically significant. Students did appreciate the flipped classroom with regard to information sharing, interaction with peers and learning from others’ experiences. |

| Kasat et. al | 50 first-year medical students were subjected to both traditional and flipped classroom modalities throughout a Gross Anatomy course. They received five traditional and five flipped course modules. Assessments were performed at the end of each module. | There was a noted to be a statistically significant increase in short-term retention of material based on assessment of the flipped classroom versus the traditional classroom. There was also noted to be increased long-term retention of material in the flipped classroom versus the traditional classroom. |

| Bhai et al. | 201 Students in 2022 Osteopathic PES course were taught using traditional classroom method, while 203 students in 2023 Osteopathic PES class were taught utilizing flipped classroom method. Overall student performance and satisfaction rates were assessed for each group. | Objective student performance was improved was statistically improved between the two groups with regard to cumulative grades and history-taking OSCE. Practical exam scores had no significant association with the flipped classroom. Student satisfaction was generally unchanged between the two teaching methods. 60% of faculty preferred the traditional classroom. |

| Sourg et. al | 63 second-year medical students were divided into traditional versus flipped classroom based on a singular lecture topic. Results were obtained comparing pre-test and post-test scores for each group. | While the pre- and post-test scores were higher in the flipped classroom group, no statistical significance was observed. Overall, more than 80% of the students were satisfied with the flipped classroom, while 90% of the students were more motivated to learn in the flipped classroom. |

| Nanjundaiah et. al | 100 phase two medical students were divided into two equal groups: flipped classroom and traditional classroom. Two separate topics were taught. At the conclusion of the first topic, the groups were reversed and the same procedure repeated topic two. Student performance and overall satisfaction were assessed for each topic. | The academic scores of the tests conducted after flipped classroom sessions were higher than those conducted after the traditional classroom sessions. This result was statistically significant. Additionally, the flipped classroom demonstrated better student involvement. |

| Chan et. al | 216 final year medical students on a 5-day Opthamology rotation were randomized into flipped classroom or traditional classroom modules. Results were collected from May 2021 to June 2022. Overall student performance and satisfaction rates were assessed for each group. | The flipped classroom students scored significantly higher on the end of rotation multiple choice exam as compared to the traditional classroom students. Flipped classroom students also rated various aspects of the course statistically higher including instructional methods, course assignments, course outcomes and course workload. They also felt more enthusiastic and engaged by the course. |

| Jha et. al | 96 phase one medical students were divided into two equal groups: flipped classroom and traditional classroom. The study was performed in an Anatomy class. Two separate topics were taught. At the conclusion of the first topic, the groups were reversed and the same procedure repeated topic two. Student performance and overall satisfaction were assessed for each topic. | Students in the flipped classroom scored higher on both the pre- and post-tests as compared to the traditional classroom students. However, only the post-test scores were noted to be significant. Perceptions towards the flipped classroom were generally positive. |

| Prabhavathi et. al | 150 first year medical students were split evenly into a traditional classroom versus flipped classroom group, and multiple topics in the cardiovascular system were taught to each group. Student performance and overall satisfaction were assessed for each group. | There was no statistically significant difference in the exam scores between the two groups. However, it was observed that the students in the flipped classroom group actively gained more knowledge, interpersonal communication skills and critical thinking skills as compared to the traditional classroom group. |

| Liu et. al | The study was performed over a 5-month period from February to July 2022 and was comprised of 71 students majoring in Clinical Medicine. These students were enrolled in a Physiology course. 32 students were placed in a group being taught via partially flipped classroom while 39 students were placed in a group being taught via traditional classroom. A three-part questionnaire was used to assess the experience of the students in each group. | Students in the partially flipped classroom group showed statistically higher scores in the deep learning approach, while the students in the traditional classroom group showed statistically higher scores in the surface learning approach. |

| Luo et al. | 119 second year students majoring in Clinical Medicine, and enrolled in a Physiology class, were split into a traditional classroom group and a flipped classroom group. Final exam scores were used to assess their learning effectiveness. | Flipped classroom teaching significantly improved the learning outcome of Physiology compared to the traditional classroom group. The study also demonstrated that students in the flipped classroom group scored higher in courses taken after their Physiology course, as compared to their classmates who were in the traditional classroom group. |

Discussion:

When comparing the flipped classroom versus the traditional classroom regarding Podiatric and Medical student education, the reviewed literature consistently demonstrates that there is, overall, improved performance and student satisfaction in those medical students participating in a flipped classroom. One explanation for the more positive student perception, as well as the greater effect of the flipped classroom over the traditional classroom, is that students have unrestricted access to the pre-recorded lectures before class. They are able to watch the lecture as many times as they wish, and at their own pace, before class. As most people have access to mobile phones and access to the internet, these pre-recorded video lectures can help deliver the information more easily and from anywhere.

Another reason that students may prefer the flipped classroom is the availability of in-class active learning time to help increase students’ understanding of the subject material. Medical quizzes are one means in which in-class time can be utilized. Medical quizzes can be case-based or image-based and can help bridge between standard classroom instruction and clinical application. At our institution, pre-and post- lecture quizzes are used to assess students’ understanding of the material studied at home, as well as the material and skills reinforced during the in-person didactic session. Case-based learning is another means by which class time may be enhanced. With case-based learning, teachers guide students as they apply new knowledge to real-world clinical issues and engage in peer learning. At our institution, students are presented with case workups based on specific clinical situations and topics. These case workups are used to assess the students’ understanding of the material presented to them. With regard to why a flipped classroom may specifically benefit medical students, previous studies have suggested that the flipped classroom is best utilized to teach higher-order skills or processing. For instance, a study by Lehman et al. demonstrated superior procedural knowledge in Pediatric Residents utilizing a blended learning classroom with virtual or video content when compared to a control group who received instruction via traditional lecture and skills station teaching. Liu et al. discussed this methodology of the flipped classroom in terms of deep learning versus surface learning. Deep learning involves intrinsic interest in the learning content, critical reading, creative problem solving, and application of learned material, while surface learning focuses on rote memorization and doing exercises solely for the purpose of passing exams. When specifically discussing application of evidence-based medicine, the traditional classroom makes it difficult for students to overcome barriers to learning because they lacked practice and real-time problem-solving skills.

The flipped classroom allows students to have discussions with their peers, and the interactive approach reduces learning gaps and helps students utilize the knowledge for clinical decisions. The ability of self-learning and cooperation can enable students to master the most advanced medical theories and medical technology, enabling them to become lifelong learners, and improve problem-solving skills, which are important traits for becoming a qualified doctor. While most of the articles utilized in this literature review demonstrated an overall positive experience for students experiencing the flipped classroom versus the traditional classroom, there are some key factors to keep in mind when it comes to the student experience. Since the flipped classroom is a student-centric method of teaching and relies heavily on student motivation and maturity levels, age at entry into medical school and curriculum can strongly influence self-directed learning readiness. Along this same line, lack of available time to understand some topics and finish their work combined with busy schedules may affect the student experience with the flipped classroom. Students against the flipped classroom reported that watching video lectures took a lot of additional time, while they also reported being unhappy being asked to do work at home that was traditionally done in a face-to-face class format. At our institution, for instance, the students participating in the flipped classroom also have clinic and patient-care responsibilities 4-5 times per week on top of preparation for their other classes. This leaves them very little time to prepare for the quizzes, case discussions, and presentations for their flipped classroom sessions. Additionally, there may be added mental pressure on students as group discussion is an integral part of the flipped classroom model, although it has been observed that students who used pre-session resources effectively took part in discussions confidently without any pressure. These facts demonstrate both positive and negative aspects of the flipped classroom.

While students are active learners and can learn and prepare in their own time; failure or inability to do so prohibits them from utilizing and maximizing the active classroom time. The main purpose of this literature review was to analyze the student experience when it comes to the flipped classroom versus the traditional classroom, and this is what most of the reviewed articles focused on. However, it is interesting to note the faculty experience with the flipped classroom versus the traditional classroom. A study by McLaughlin et al. suggested that to flip a classroom, an educator must invest 127% more time in course development and 57% more time to maintain that course than a traditional lecture. On average, a 15-minute online lecture required two to three hours of production and editing. On the same note, however, once pre-class material is recorded or prepared, online courses and materials can be used on multiple, consecutive cohorts. Bhai et al. found that 60% of the faculty preferred traditional classroom teaching in a survey of 16 core faculty members, of which 10 responded. Of note, a primary concern raised by the faculty was that students come to class without watching the videos.

Conclusions:

Based on this literature review, the flipped classroom approach can yield increased medical student performance as well as increased student satisfaction in the classroom as compared to the traditional classroom approach. As medicine evolves, and technology changes, the flipped classroom approach appears to be beneficial in improving critical thinking and problem solving in medical school students.

Future Considerations:

All 15 of the articles from this literature review studied medical students in their pre-clinical years. Only one study was found which studied Podiatry students specifically, but these students were pre-clinical as well. It may be beneficial to carry out further studies on the specific benefits of the flipped classroom in Podiatric, Allopathic, and Osteopathic medical students in their clinical courses.

Disclosures:

The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

References:

- Smith KM, Geletta S, Duelfer K. Flipped Classroom in Podiatric Medical Education. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2020 Sep 1;110(5):Article_11. doi: 10.7547/19-060. PMID: 33179058.

- Tsao YP, Yeh WY, Hsu TF, Chow LH, Chen WC, Yang YY, Shulruf B, Chen CH, Cheng HM. Implementing a flipped classroom model in an evidence-based medicine curriculum for pre-clinical medical students: evaluating learning effectiveness through prospective propensity score-matched cohorts. BMC Med Educ. 2022 Mar 16;22(1):185. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03230-z. PMID: 35296297; PMCID: PMC8925289.

- Wang, L, Xia Y, Qiu C, Yuan, S, Liu X. Comparative studies of the differences between flipped class and traditional class in Orthopedic Surgery Education. Frontiers Education. 9:1382948. 2024 Jul 4.

- Liu Z, Xu Y, Lin Y, Yu P, Ji M, Luo Z. A partially flipped physiology classroom improves the deep learning approach of medical students. Adv Physiol Educ. 2024 Sep 1;48(3):446-454. doi: 10.1152/advan.00196.2023. Epub 2024 Apr 11. PMID: 38602011.

- Phillips J, Wiesbauer F. The flipped classroom in medical education: A new standard in teaching. Trends Anaesth Crit Care. 2022 Feb;42:4-8. doi: 10.1016/j.tacc.2022.01.001. Epub 2022 Jan 13. PMID: 38620968; PMCID: PMC9764229.

- Jha S, Sethi R, Kumar M, Khorwal G. Comparative Study of the Flipped Classroom and Traditional Lecture Methods in Anatomy Teaching. Cureus. 2024 Jul 11;16(7):e64378. doi: 10.7759/cureus.64378. PMID: 39130849; PMCID: PMC11316939.

- Khadawardi K, Mirdad D, Nasief H, Hassan A, Waseem H, Butt A, Aldardeir NE, Salah W, Zakariyah AF, Alboog A. Evaluating Medical Student Engagement in Flipped Classrooms: Insights on Motivation and Peer Learning. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2025 Feb 26;12:23821205251320756. doi: 10.1177/23821205251320756. PMID: 40018368; PMCID: PMC11866390.

- Malhotra AS, Bhagat A. Flipped classroom for undergraduate medical students in India: are we ready for it? Adv Physiol Educ. 2023 Dec 1;47(4):694-698. doi: 10.1152/advan.00200.2022. Epub 2023 Jul 20. PMID: 37471219.

- Nanjundaiah, Komala; Anuradha, H. V. Comparison of Flipped Classroom Versus Traditional Didactic Lectures among Medical Students: A Mixed Method Study. National Journal of Clinical Anatomy 13(1):p 41-44, Jan–Mar 2024. | DOI: 10.4103/NJCA.NJCA_184_23.

- Prabhavathi K, KalyaniPraba P, Rohini P, Selvi KT, Saravanan A. Flipped classroom as an effective educational tool in teaching physiology for first-year undergraduate medical students. J Educ Health Promot. 2024 Jul 29;13:283. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_1854_23. PMID: 39310021; PMCID: PMC11414885.

- Blair RA, Caton JB, Hamnvik OR. A flipped classroom in graduate medical education. Clin Teach. 2020 Apr;17(2):195-199. doi: 10.1111/tct.13091. Epub 2019 Sep 11. PMID: 31512400; PMCID: PMC7064372.

- Bhavsar MH, Javia HN, Mehta SJ. Flipped Classroom versus Traditional Didactic Classroom in Medical Teaching: A Comparative Study. Cureus. 2022 Mar 30;14(3):e23657. doi: 10.7759/cureus.23657. PMID: 35510025; PMCID: PMC9060739.

- Alnahdi M, Agha S, Khan MA, Almansour M. The Flipped Classroom Model: Exploring The Effect On The Knowledge Retention Of Medical Students. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2022 Oct-Dec;34(4):755-761. doi: 10.55519/JAMC-04-10957. PMID: 36566394.

- Kasat P, Deshmukh V, Muthiyan G, T S G, Sontakke B, Sorte SR, Tarnekar AM. The Role of the Flipped Classroom Method in Short-Term and Long-Term Retention Among Undergraduate Medical Students of Anatomy. Cureus. 2023 Sep 11;15(9):e45021. doi: 10.7759/cureus.45021. PMID: 37829972; PMCID: PMC10566247.

- Bhai, Sahar Amin and Poustinchian, Brian. “The flipped classroom: a novel approach to physical examination skills for osteopathic medical students” Journal of Osteopathic Medicine, vol. 121, no. 5, 2021, pp. 475-481. https://doi.org/10.1515/jom-2020-0198.

- Sourg HAA, Satti S, Ahmed N, Ahmed ABM. Impact of flipped classroom model in increasing the achievement for medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2023 Apr 27;23(1):287. doi: 10.1186/s12909-023-04276-3. PMID: 37106403; PMCID: PMC10142149.

- Ji M, Luo Z, Feng D, Xiang Y, Xu J. Short- and Long-Term Influences of Flipped Classroom Teaching in Physiology Course on Medical Students’ Learning Effectiveness. Front Public Health. 2022 Mar 28;10:835810. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.835810. PMID: 35419334; PMCID: PMC8995769.

- Zheng B, Zhang Y. Self-regulated learning: the effect on medical student learning outcomes in a flipped classroom environment. BMC Med Educ. 2020 Mar 31;20(1):100. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02023-6. PMID: 32234040; PMCID: PMC7110809.

- Chan PP, Lee VWY, Yam JCS, Brelén ME, Chu WK, Wan KH, Chen LJ, Tham CC, Pang CP. Flipped Classroom Case Learning vs Traditional Lecture-Based Learning in Medical School Ophthalmology Education: A Randomized Trial. Acad Med. 2023 Sep 1;98(9):1053-1061. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000005238. Epub 2023 Apr 14. PMID: 37067959.

- Hew KF, Lo CK. Flipped classroom improves student learning in health professions education: a meta-analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2018 Mar 15;18(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1144-z. PMID: 29544495; PMCID: PMC5855972.

- Nichat A, Gajbe U, Bankar NJ, Singh BR, Badge AK. Flipped Classrooms in Medical Education: Improving Learning Outcomes and Engaging Students in Critical Thinking Skills. Cureus. 2023 Nov 3;15(11):e48199. doi: 10.7759/cureus.48199. PMID: 38054140; PMCID: PMC10694389.

- Phillips J, Wiesbauer F. The flipped classroom in medical education: A new standard in teaching. Trends Anaesth Crit Care. 2022 Feb;42:4-8. doi: 10.1016/j.tacc.2022.01.001. Epub 2022 Jan 13. PMID: 38620968; PMCID: PMC9764229.

- McLaughlin JE, Roth MT, Glatt DM, Gharkholonarehe N, Davidson CA, Griffin LM, Esserman DA, Mumper RJ. The flipped classroom: a course redesign to foster learning and engagement in a health professions school. Acad Med. 2014 Feb;89(2):236-43. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000086. PMID: 24270916.

- Wagner, D., Laforge, P., & Cripps, D. (2013). Lecture Material Retention: a First Trial Report on Flipped Classroom Strategies in Electronic Systems Engineering at the University of Regina. Proceedings of the Canadian Engineering Education Association (CEEA). https://doi.org/10.24908/pceea.v0i0.4804.