Food, Nutrition, and Gut Health: Mechanisms Explained

Understanding the Mechanisms and the Impact of Food and Nutrition on Gut Health: A Narrative Review

David Ehrenberg, B.S. 1; Christen Cupples Cooper, Ed.D, RDN 2

- David Ehrenberg, BS Human Biology, SUNY Albany; Coordinated M.S in Nutrition and Dietetics Candidate, Pace University, NY, USA

- Christen Cupples Cooper, Ed.D, RDN Program Founder and Associate Professor, Coordinated M.S. in Nutrition and Dietetics Program, Pace University, NY, USA

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 April 2025

CITATION:Ehrenberg, D., and Cooper, CC., 2025. Understanding the Mechanisms and the Impact of Food and Nutrition on Gut Health: A Narrative Review. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(4). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i4.6400

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i4.6400

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

This narrative review analyzes the literature on known physiological mechanisms impacting gut dysbiosis and how optimal nutrition, including high-fiber, probiotic-rich foods in a whole food diet may positively impact patient health outcomes. Additional topics include understanding the current state of research regarding: inflammation, immunity, mental health, chronic diseases, and pro-gut dietary patterns. The study in this review explores the intricate relationship between the gut microbiome and systemic health, highlighting the role of nutritional interventions, prebiotics, probiotics, and lifestyle modifications in restoring microbial balance. By synthesizing current evidence, this paper aims to provide insights into personalized nutrition strategies supporting gut health and overall well-being while identifying research gaps warranting further investigation.

Keywords

- gut health

- nutrition

- dysbiosis

- microbiome

- probiotics

- prebiotics

- chronic diseases

- inflammation

Introduction

The gut microbiota, the body’s largest symbiotic ecosystem, is one of the most critical factors in human health and is crucial in maintaining intestinal balance. Dysbiosis, or disruption of the gut microbiome, is commonly defined as a decrease in microbial diversity, the presence of potentially harmful microbes, or the absence of beneficial ones. This imbalance has been linked to a variety of health issues ranging from Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), Diabetes, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and CVD to immunoinflammatory responses, depression, and other mental health disorders, highlighting the impact of gut health on overall well-being. Conversely, gut homeostasis represents a state where host functions that control microbial growth are normal (i.e., characteristic of a healthy or normally functioning individual).

It is widely acknowledged that diet significantly shapes the composition of the gut microbiota. Gut microbes utilize diet-derived nutrients for their growth and colonization in the gut. Conversely, host cells use microbial metabolites as energy sources and immunomodulatory agents to maintain intestinal homeostasis. This underscores the profound impact of dietary choices on gut health and overall well-being. Understanding this relationship and making informed decisions about our diet is paramount, as it contributes to a balanced microbiome and reduces the risk of dysbiosis and associated health issues.

The gut microbiota involves numerous physiological processes impacting host health, mainly via immune system modulation. A balanced microbiome contributes to the gut’s barrier function, preventing the invasion of pathogens and maintaining the integrity of the gut lining. The human body harbors many microbiota—on the skin, gut, genitals, and other tissues—which are beneficial and involved in various vital functions. They protect the body from the penetration of pathogenic microbes. These microbiotas contribute to metabolism and nutrition, which are important for human health; therefore, a balance in the composition of these commensal organisms is crucial to maintaining homeostasis.

NUTRIENT ABSORPTION

Research shows that an enriched and diverse gut microbiota promotes nutrient absorption and vitamin synthesis and enhanced cellular mechanisms benefiting the host. The unique environments within different gut compartments (such as the small and large intestines) influence microbiota composition. Moving down from the upper digestive tract—starting with the oral cavity and esophagus—the duodenum and jejunum exhibit lower microbial diversity than the ileum or proximal colon. The gut microbiota is predominantly composed of four key bacterial species—Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, and Actinomycetes—accounting for more than 98% of the gut microbiota, with approximately 2,172 total species in the gut. The small intestine is predominantly populated by Gram-positive Firmicutes, including genera such as Streptococcus, Veillonella, and Clostridium. In contrast, the colon hosts different dominant bacterial groups, especially strict anaerobes. The distal small intestine has higher abundances of bacterial phyla such as Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria. The large intestine, composed of the cecum, ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid colon, rectum, and anus, harbors rich and highly diverse microbial communities, primarily consisting of two bacterial phyla in healthy individuals: Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes. Examining the microbial communities within the small intestine and colon displays crucial insights into their specialized roles in digestion, immune regulation, and overall gut health. The makeup of these species can vary greatly between individuals due to dietary patterns, environment, and lifestyle, further highlighting the significance of personalized nutritional and health interventions to maintain optimal gut health. A reduction of microbial diversity and the outgrowth of Proteobacteria are cardinal features of dysbiosis.

The gut symbiotic microbiota also participates in bile metabolism, aiding in the digestion, transport, and absorption of nutrients. This elaborate process is integral to signaling pathways regulating cholesterol levels, glucose metabolism, and immune response. Bile acids are a class of bioactive metabolites that signal through bile acid receptors, such as FXR (farnesoid X receptor) and TGR5 (Takeda G protein-coupled receptor 5), to improve metabolic health. The liver and the gut microbiota primarily metabolize bile acids. Primary bile acids are produced in the liver from cholesterol and conjugate with taurine or glycine before secretion into the gut lumen. Bacteria in the cecal colon, such as Clostridium in Firmicutes, produce enzymes that convert primary bile acids to secondary bile acids. This conversion adds another layer of regulation, as secondary bile acids impact microbial composition and intestinal health. The microbiota influences fat-soluble vitamin absorption via bile metabolism, essential for various bodily functions, including vision, bone health, and immune function. Bile acids are primarily produced by humans to catabolize cholesterol and play crucial roles in gut metabolism, microbiota habitat regulation, and cell signaling. The gut microbiota synthesizes SCFAs (short chain fatty acids), polyamines, and vitamins. The degradation of dietary fibers by gut microbiota produces organic acids, gases, and a large amount of SCFA. Acetate (C2), propionate (C3), and butyrate (C4) are the main SCFA produced (60:20:20 mM/kg in the human colon). Indigestible carbohydrates are fermented by the gut microbiota to produce butyrate, the primary fuel for colon wall cells, which is known for its anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory properties. SCFAs can regulate pH, affect bacterial metabolism, and inhibit the expression of virulence genes in pathogens. Then, gut microbiota competes with pathogens for nutritional niches and physical niches to inhibit the growth and proliferation of pathogens. In addition, the host’s immune system can be stimulated by gut microbiota to produce antimicrobial peptides and anti-inflammatory factors to enhance immune barrier function and clear pathogens. Furthermore, a decreased abundance of SCFA-producing bacteria or decreased genomic potential for SCFA production have been identified in many studies, such as type-1 diabetes, type-2 diabetes, liver cirrhosis, inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), and atherosclerosis.

CELL PROLIFERATION AND DIFFERENTIATION

Through the production of SCFA, gut microbiota also actively communicates with host cells and strongly modulates various cellular mechanisms. Two of the main functions influenced by SCFA and, thus, gut microbiota are cell proliferation and differentiation. Cell proliferation refers to the process by which cells grow and divide to produce new cells. The regulation of cell proliferation is critical for tissue development, maintenance of homeostasis, and disease suppression. Proliferation ensures that there are enough cells to replace old, damaged, or dying cells, maintaining the proper function of tissues and organs. It is tightly regulated to prevent uncontrolled growth. Uncontrolled proliferation results in hyperplasia, a hallmark of cancerous mutations. Cell differentiation is the process during which young, immature (unspecialized) cells take on individual characteristics and reach their mature (specialized) form and function. During differentiation, cells acquire specific characteristics that enable them to perform specialized roles, such as becoming muscle cells, nerve cells, or epithelial cells. This process is crucial for the development of complex organisms and for maintaining the specialized functions of tissues throughout life. SCFA broadly impacts the host: metabolism, differentiation, and proliferation, mainly due to its implications for gene regulation. Several studies revealed that butyrate regulates the expression of 5–20 % of human genes. In a colonic cell line, 75 % of the upregulated genes are dependent on the ATP citrate lyase activity, and 25 % are independent at 0.5 mM concentration. Still, the proportion is reversed at high concentrations (5 mM). This suggests that the gene regulation mechanisms differ depending on the butyrate concentration. Therefore, through their capacity to modulate gene expression in a concentration-dependent manner, SCFA plays a pivotal role in regulating critical cellular processes such as proliferation and differentiation, highlighting their importance in maintaining tissue homeostasis, supporting development, and potentially influencing the progression of diseases, including cancer.

Methods

This study is a literature review of studies conducted on the potential effects, therapeutic applications, and connections between food, nutrition, and gut dysbiosis. Between September 2024 and December 2024, PubMed, MEDLINE, and CINHAL were searched for relevant, peer-reviewed studies on gut dysbiosis and nutrition. The search utilized the key words: “Gut dysbiosis and: “nutrition, inflammation, mental health, chronic disease, probiotics, immunity, immune system, type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, diet, short chain fatty acids (SCFAs), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), micronutrients, nutrient imbalances, dietary patterns, therapeutic diet, Western diet, butyrate, gut microbiome, and bacteria. Journals from across the health professions were included in this study. Excluded studies were those published more than ten years before the publication of this review. This review did not limit the span of studies to only those published in the United States, but did limit to studies published in English.

Results

Gut dysbiosis is characterized as a decrease in microbial diversity and has been linked to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), irritable bowel disease (IBS), Type 2 Diabetes, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and cardiovascular disease (CVD) to immunoinflammatory responses, depression, and altered nutrient absorption. Immune dysfunction arises as dysbiosis weakens mucosal defenses, increases systemic inflammation, and heightens susceptibility to infections and autoimmune disorders as 70–80% of immune cells in the gut. Gut dysbiosis disrupts the balance of beneficial and pathogenic gut bacteria, impairing the digestion and absorption of essential nutrients. Reducing beneficial bacteria such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium can lead to decreased short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) production. According to research, it has been concluded that dysbiosis affects the gut-brain axis by altering neurotransmitter production, contributing to anxiety, depression, and cognitive decline. Studies indicate that an overgrowth of pro-inflammatory bacteria and a decrease in Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium populations can contribute to increased systemic inflammation and heightened stress responses, exacerbating symptoms of anxiety and depression. Furthermore, research has linked gut dysbiosis to an increase in chronic disease. Research indicates that the overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria promotes systemic inflammation and insulin resistance, increasing the risk for obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. In contrast, probiotic-rich foods like yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, kimchi, and kombucha supply live beneficial bacteria to support gut health further. Polyphenol-rich foods, including berries, green tea, and dark chocolate, encourage the growth of good microbes. Healthy Fats like omega-3 fatty acids and dietary fiber can reduce gut inflammation and support the integrity of the gut lining, a key nutrient for maintaining the diversity of gut microbiota.

The Immune System

The immune system, an intricate network of cells, tissues, and organs, functions as the body’s primary defense against pathogens and environmental threats, continuously balancing protection with tolerance to avoid unnecessary inflammation or autoimmunity. The immune system is crucial in these infections’ susceptibility, persistence, and clearance. With 70–80% of immune cells in the gut, there is an intricate interplay between the intestinal microbiota, the intestinal epithelial layer, and the local mucosal immune system. The commensal microbiome regulates the maturation of the mucosal immune system, while the pathogenic microbiome causes immunity dysfunction, resulting in disease development. The immune system comprises two parts: the innate immune system and the adaptive immune system. The innate immune system provides nonspecific protection by several defense mechanisms, which include physical barriers such as the skin and mucous membranes, chemical barriers like enzymes and antimicrobial proteins, and innate immune cells, including granulocytes, macrophages, and natural killer cells. The adaptive immune system cells, T- and B-lymphocytes, recognize and respond to specific foreign antigens. T cells recognize infectious agents that have entered into host cells. This type of adaptive immunity depends on the direct involvement of cells and is, therefore, referred to as cellular immunity. T cells also play an essential role in regulating the function of B cells that secrete antibodies and proteins that recognize specific antigens. Because antibodies circulate through the humorous (i.e., body fluids), the protection induced by B cells is termed humoral immunity. The innate and adaptive immune systems provide a comprehensive defense, balancing immediate, nonspecific responses with targeted, long-term immunity.

Immune organs, immune cells, soluble cytokines, and cell receptors regulate the immune system. The intestine mucosal immune system consists of three mucosal lymphoid structures: Peyer’s patches, the lamina propria, and the epithelia. The mucus layer on the surface of epithelial cells is the first line of defense in the organism’s physiological barrier. Epithelial cells are the second physical barrier of the intestinal mucosal immune system, and they directly participate in the immune surveillance of the gut. Epithelial cells are involved in the direct defense against microorganisms and send signals to the mucosal immune system by producing cytokines and chemokines. The lamina propria, which consists of B and T cells, resides in the lower layer of intestinal epithelial cells. T cells quickly respond to the signal from the lumen environment and initiate inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses. This intricate interplay between structural barriers, cellular components, and signaling molecules within the intestinal mucosal immune system highlights its critical role in maintaining gut health and orchestrating balanced immune responses.

The intestinal microbiota and mucosal immune system maintain a dynamic and reciprocal relationship essential for sustaining intestinal homeostasis. Beyond aiding in the digestion and fermentation of food necessary for the production of specific vitamins, the microbiota is also crucial in the defense against pathogens once they compete for nutrients and adhesion sites, some even actively eliminating competition by secreting antimicrobial peptides. The significant products that result from bacterial fermentation of fibers in the colon are short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including acetic acid, butyric acid, and propionic acid, which gain access through the intestinal epithelia and can interact with host cells, thus influencing immune responses and disease risk. Short chain fatty acids are not only important energy sources for the gut microbiota and Intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) but also have diverse regulatory functions in host physiology and immunity, generally regarded as beneficial metabolites with anti-inflammatory properties. Maintaining a diverse and balanced microbiota is critical, as disruptions in microbial composition can weaken intestinal barrier integrity and promote chronic inflammation.

The gut microbiota composition and dietary fiber availability significantly affect SCFA concentrations in the colon. A diet rich in fibers can favor the presence of bacteria capable of cellulose and xylan hydrolysis, including members of the genus Prevotella, Xylanibacter, and the butyrate-producing Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. It has also been hypothesized that a high abundance of F. prausnitzii, along with other SCFA-producing bacteria, could protect the host from inflammation and noninfectious colonic diseases. To that effect, reports have correlated a low abundance of F. prausnitzii with Crohn´s Disease (CD) and other inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs). A study of 62 critically ill patients showed that higher diversity and relative abundance (RA) of Prevotella and Bacillales families was associated with a lower risk of colonization by resistant organisms, infection, and death. In contrast, Enterococcaceae family RA was associated with an increased risk of infection and death.

The absence of specific bacteria in the gut is just as important as the presence of others. Even slight differences in the abundance of healthy gut bacteria have been implicated in diverse systemic diseases. Butyrate, a key SCFA, supports epithelial barrier function by enhancing tight junction assembly and acts as a signaling molecule to modulate immune cell activity. For example, butyrate is the primary energy source for the epithelial cells that line the colon. Without butyrate, these cells starve, shrivel, and degrade. Butyrate also dampens the intestinal and systemic immune response by stimulating the development of regulatory T cells. In gut microbiome studies in critically ill patients, butyrate-producing bacteria are uncommon or absent, and butyrate production is minimal. Studies have shown that HDAC enzymes are involved in maintaining microbiome-dependent intestinal homeostasis; in particular, HDAC3, a class I histone deacetylase that is highly expressed in the intestinal epithelium, is sensitive to microbial signaling. SCFAs inhibit HDACs, often increasing histone acetylation at direct targets. HDAC inhibitors are widely used in cancer therapy and have also been reported to have anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressive functions. Butyrate and, to a lesser extent, propionate are known to act as HDAC inhibitors, with butyrate being the most potent and widely studied. The inhibitory efficiency of butyrate on HDAC1/2 can reach about 80%. It has been reported that butyrate and propionate can balance pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mechanisms by promoting peripheral Treg production. This helps to maintain intestinal immune homeostasis. Gut microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic Tregs by enhancing histone H3 acetylation in the promoter and conserved non-coding sequence regions of the Foxp3 locus and reduces the development of colitis. Therefore, SCFAs may act as modulators of cancer and immune homeostasis.

Mental Health

The study of gut microbiota affecting mental health is a relatively new research topic that has gained popularity these past years. Immune system dysregulation, microbial imbalances in the gut, and mental health highlight a bidirectional connection where immune or gut homeostasis disruptions can contribute to neuroinflammation, altered neurotransmitter production, and increased susceptibility to mental health disorders. Depression is a serious mental illness caused by multiple factors. It is described as low emotional disposition, loss of confidence, and apathy. Major depressive disorder (MDD) tops the spot in contributing to the worldwide disease burden, as claimed by the World Health Organization (WHO). Based on the WHO reports, there are approximately 350 million people affected by depression. Research findings showed that healthy gut microflora transmits brain signals through the pathways involved in neurogenesis, neural transmission, microglial activation, and behavioral control under stable or stressful conditions. In depression, there is also dysregulation of the neuroendocrine and neuroimmune pathways. More than 20% of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) patients have sleep disturbances and depressed behaviors.

Most immune cells within the human body are found within the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), reflecting the importance of this immune tissue in maintaining host health. Alterations in gut microbiota composition can lead to increased production of microbial lipopolysaccharides (LPS), which are potent activators of inflammatory pathways. The LPS-induced inflammation triggers cytokine release, which communicates with the central nervous system (CNS) via the vagus nerve, linking gut dysbiosis to hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activation and subsequent behavioral and neuroendocrine changes. Contemporary studies have identified potential associations between anxiety and depression symptoms with an overabundance of proinflammatory bacteria such as Enterobacteriaceae and Desulfovibrio and a decrease in SCFA-producing bacteria like Faecalibacterium. Short-chain fatty acids, essential for anti-inflammatory signaling, are notably diminished in such microbial profiles, potentially exacerbating systemic and neuroinflammation. Anxiety disorders, among the most prevalent mental health conditions, are increasingly linked to distinct microbial imbalances. For instance, a study found that the abundance of Prevotella was increased. In contrast, the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio and the abundance of Faecalibacterium spp. were significantly reduced in individuals with social exclusion. Additionally, patients with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) had lower microbial richness and diversity and reduced Firmicutes spp. and microbiota levels that produce SCFAs but more Fusobacteria and Bacteroidetes. This microbial shift impacts gut health and disrupts critical gut-brain communication, potentially perpetuating a cycle of inflammation and mental health deterioration.

Chronic Diseases

Features of the gut microbiota have been associated with several chronic diseases and longevity, underscoring its critical role in human health. Research suggests that the composition and diversity of gut microbial communities influence metabolic processes, immune responses, and inflammatory pathways. The gut microbiota plays a pivotal role in obesity, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), insulin resistance, and chronic inflammation, all of which are key contributors to developing type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Obesity is a complex, multifactorial disease due to various factors, including the host’s genetic background, decreased physical activity, and excess food intake. In the last few decades, the gut microbiota has been proposed as an additional factor favoring fat storage, weight gain, and insulin resistance. The gut microbiota is involved in energy homeostasis by extracting energy from foodstuffs through fermentation processes and forming short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). It also increases villous vascularization, improving nutrient absorption and decreasing AMPK levels and ß-oxidation in the muscular tissue. In addition, the microbiota modulates and inhibits the release of fasting-induced adipose factor (Fiaf), an inhibitor of lipoprotein lipase (LPL) activity, resulting in the subsequent storage of triglycerides in the adipose tissue and liver. Furthermore, it influences the development of metabolic endotoxemia and low-grade inflammation. Diabetes is a group of metabolic diseases characterized by hyperglycemia caused by the direct or indirect deficiency of insulin. Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is an autoimmune disease in which antibodies are produced against various elements of pancreatic β-cells; the islets producing insulin deteriorate and, eventually, are destroyed, which causes a lack of insulin. Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is triggered by insulin resistance (IR), leading to an increased demand of peripheral tissues for insulin and, consequently, causes the functional failure of β-cells. Diabetes is growing at an alarming rate in the United States. According to the CDC’s (Centers for Disease Control) National Diabetes Statistics Report for 2022, cases of diabetes have risen to an estimated 37.3 million. An estimated 28.7 million people have been diagnosed with diabetes. Approximately 8.6 million people have diabetes but have not yet been diagnosed. In 2019, 283,000 children and adolescents younger than 20 years were diagnosed with diabetes. This includes 244,000 with type 1 diabetes. However, in family and twin studies, it has been proved that only 20–30% of genetically predisposed individuals carrying these alleles will develop T1D. Poor metabolic control of diabetes can result in severe long-term complications, such as retinopathy, chronic kidney disease, neuropathy, cardiovascular disease, and elevated mortality risk.

The microbiota of healthy adults consists of six phyla—Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, the major groups of bacteria, but also Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Fusobacteri, and Verrucomicrobia. Several studies have provided information about an altered gut microbiota in T1D-affected patients. Giongo et al. indicated that a high Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio and the instability of the microbiota could be one of the early diagnostic markers of developing autoimmune disorders, such as T1D. Furthermore, in diabetic children, there was an increased level of Bacteroidetes and Streptococcus mitis. At the same time, in healthy controls, there was a higher prevalence of the butyrate producers Lactobacillus plantarum and Clostridium clusters IV and XIVa. In early childhood, the factors that can modify the composition of the intestinal microbiota include breastfeeding, nutrition, route of delivery, use of antibiotics, and exposure to the microbes in the environment. Their action can result in intestinal barrier disruption and defective maturation of the immune response. Intestinal inflammation and the reduction of SCFAs caused by dysbiosis can be crucial to the pathogenesis of T1D. Similarly to T1D, the microbiota in patients with T2D differ from those occurring in healthy individuals. The main change seen in various research is an increase in opportunistic pathogens and a decrease in bacteria-producing butyrate, one of the SCFAs. One of the first studies on the microbiota of subjects with T2D, conducted by Larsen et al., showed decreased levels of the phylum Firmicutes and class Clostridia. Moreover, the Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes ratio and the Bacteroidetes-Prevotella/C. coccoides-E. Rectal ratio was positively correlated with plasma glucose concentration. The results of various studies differ from one another, but, in general, the genera negatively associated with T2D are Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, Faecalibacterium, Akkermansia, and Roseburia, and the genera Fusobacteria, Ruminococcus, and Blautia are positively connected with this disease. Furthermore, Researchers found 43 bacterial taxa significantly differed between obese Chinese individuals with T2DM and healthy people by LEfSe analysis and Acidaminococcales, Bacteroides plebeius, and Phascolarctobacterium sp.CAG207 might be a potential biomarker for T2DM. T2DM patients showed an increase in multiple pathogenic bacteria, such as Clostridium hathewayi, Clostridium symbiosum, and Escherichia coli, while healthy controls had a high abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria. Importantly, Lactobacillus species were positively correlated with fasting glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c). In contrast, Clostridium species were negatively correlated with fasting glucose, HbA1c, and plasma triglycerides, suggesting that these bacterial taxa might be related to the development of T2DM. Similarly, the levels of Lactobacillus were significantly increased, while the levels of Clostridium coccoides and Clostridium leptum were significantly decreased in newly diagnosed T2DM patients.

The gut microbiota is closely associated with a variety of diabetic complications, such as diabetic nephropathy (DN), diabetes-induced cognitive impairment (DCI), diabetic retinopathy (DR), and diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN). Chronic uncontrolled diabetes is associated with diabetic neuropathy, a neurodegenerative nutritional disease characterized by damage to peripheral nerves, causing pain and numbness. Diabetic neuropathy is present in approximately 50% of diabetic patients. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy has been associated with certain factors, such as oxidative stress, activation of the polyol pathway, and inflammation, and linked to changes in the diversity of the gut microbiota and the increased presence of pathogens. A comparison of the gut microbiota in patients with diabetic neuropathy, patients with diabetes without diabetic neuropathy, and healthy individuals showed an increase in Firmicutes and Actinobacteria as well as a decrease in Bacteroidetes in patients with diabetic nephropathy when compared to patients with diabetes without diabetic neuropathy and healthy individuals. These findings underscore the critical role of gut microbiota alterations in diabetic complications, particularly neuropathy, by driving inflammation and metabolic dysregulation. The guts’ role extends beyond metabolic health, with significant implications for inflammatory conditions such as Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS).

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is the most prevalent functional gastrointestinal disorder in the industrialized world. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is the most common functional digestive condition in the industrialized world and is characterized by recurrent abdominal pain and altered bowel movements. IBS has a prevalence of approximately 11% worldwide and has associated comorbidities, such as anxiety, depression, fibromyalgia, migraine headaches, chronic fatigue, and others. IBS is heterogeneous in its clinical presentation and is commonly subtyped according to the predominant bowel habit using the Rome IV criteria into IBS with constipation predominance (IBS-C), IBS with diarrhea predominance (IBS-D), mixed IBS with both constipation and diarrhea, and unsubtyped IBS with neither predominant constipation nor diarrhea.

There is evidence that a distortion in the biodiversity and composition of the gut microbiota, known as gut dysbiosis, plays a fundamental role in the pathogenesis of IBS. A systematic review and meta-analysis of findings from 23 studies and 1,340 participants underscored the association of IBS with gastrointestinal dysbiosis. Specifically, a deficiency of the commensal genera Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium and an overgrowth of potentially pathogenic populations of Enterobacteriaceae and E coli was found in patients with IBS compared to healthy controls. The gut microbiome plays a central role in regulating several processes that contribute to the pathophysiology of IBS. Commensals like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium may help mitigate IBS disease pathogenesis and improve symptoms. IBS, with its high prevalence and chronic nature, poses substantial challenges to both individual quality of life and healthcare systems. Conversely, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) encompasses a distinct group of disorders defined by persistent gastrointestinal inflammation and complex immune dysregulation.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which includes ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), is a chronic and relapsing inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal tract. CD may affect any area of the gastrointestinal tract, and its involvement is transmural; colonoscopy findings include skip lesions, cobblestoning, ulcerations, and strictures. UC generally occurs only in the colon and involves the mucosa and submucosa; classically described colonoscopy findings are pseudopolyps and continuous areas of inflammation. It is estimated that approximately 3 million people (1.3%) in the US population suffer from IBD. IBD affects roughly 2.5 million people in Europe. In North America, incidence rates for CD range from 0 to 20.2 per 100,000 persons/years and from 0 to 19.2 per 100,000 persons/years for UC. Although the precise etiology of IBD is mainly unknown, it is widely thought that diet contributes to the development of IBD. The intake of specific diets, such as the Westernized diet characterized by high fat and low fiber, results in gut dysbiosis, thereby disrupting intestinal homeostasis and promoting inflammation of the gut.

IBD is associated with intestinal dysbiosis. Changes in the microbiome have a pivotal role in determining the onset of the pathology when the individual’s genetic background makes him/her predisposed and other concomitant environmental factors intervene. Genetic studies have identified over 200 host genetic loci associated with the risk of IBD, primarily related to immunological pathways, including innate and adaptive immune responses and autophagy. Early retrospective case-control studies identified a Westernized diet characterized by a higher intake of meat and fats, particularly polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), and a lower intake of fiber, fruits, and vegetables as the risk for IBD pathogenesis. Interestingly, the NHS identified the role of a gene-diet interaction in the development of IBD. The study demonstrated that the variants in CYP4F3, which are involved in PUFA metabolism, may modify the association between n-3 and n-6 PUFA intake and the risk of UC. Specifically, high intake of n-3/n-6 PUFAs was associated with a reduced risk of UC in individuals with the GG/AG genotype at a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in CYP4F3 but not in those with the AA genotype.

Results of studies aimed at characterizing the microbiota of patients suffering from IBD, even sometimes with checkered results, indicate a generalized decrease in biodiversity, measured by an appropriate parameter—alpha—as well as a reduction in specific taxa, including Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, Lactobacillus, and Eubacterium. IBD patients also present a reduction in species producing butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid positively modulating intestinal homeostasis and reducing inflammation. A concomitant taxonomic shift has also been observed, with a relative increase in Enterobacteriaceae, including Escherichia coli and Fusobacterium. Joossens et al. (2011) observed increased Ruminococcus gnavus and decreased Bifidobacterium adolescentis, Dialister invisus, and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in CD patients, alongside an unspecified member of Clostridium cluster XIVa. There is broad consensus that IBD is characterized by a reduced total number of species and diminished microbiota diversity.

Emerging research reveals a striking connection between cardiovascular disease (CVD) and gut dysbiosis. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading global cause of death, accounting for 17.3 million deaths globally per year and one of every three deaths in the United States. CVD is a term used to describe a variety of diseases and disorders that affect the blood vessels and, ultimately, the heart. Atherosclerosis, heart failure, and hypertension are a few among several conditions that can result in CVD. Known risk factors leading to these conditions include smoking, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and gut dysbiosis, which may also contribute extensively to the progression of CVD. Changes in the composition of intestinal microbiota have been described in the context of several types of cardiovascular disease (CVD), characterized by an impaired Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio and/or reduction in the prevalence of butyrate-producing bacteria in patients, including those with heart failure (HF), compared to healthy subjects. Regarding the gut, impaired cardiac function causes reduced intestinal perfusion, mucosal edema, and changes in local pH, which can alter the microbiota composition, as described in previous studies comparing HF with non-HF subjects. It has been suggested that gut microbiota dysbiosis, together with changes in the intestinal barrier, particularly the mucosa layer, can alter its permeability and allow translocation into the circulation of bacterial fragments – such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), an endotoxin – and products of the bacteria and host co-metabolism of dietary components.

Other mechanisms have been suggested to explain the link between dysbiosis and CVD, including producing metabolites with proatherosclerotic and prothrombotic properties, especially trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO). Trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), a small-molecule metabolite, has recently been believed to serve as a link between the gut microbiota and host progression to CVD. Trimethylamine (TMA) is the waste product produced after TMA-containing nutrients, such as phosphatidylcholine, choline, and carnitine, are fermented by gut microbes as a carbon fuel source. TMA is taken to the liver via the portal circulation and is converted into TMAO by a host enzyme, hepatic flavin monooxygenase (FMO). Foods rich in choline include eggs, milk, liver, red meat, and poultry and are, therefore, sources of TMA, with which the host can produce TMAO. In a human study, more than 1800 patients undergoing elective coronary angiography showed that all TMA metabolites, including choline, had a positive association with prevalent CVD and incident cardiovascular events. In a subsequent study of over 4000 patients undergoing elective coronary angiography, elevated TMAO levels were associated with an increased risk of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke over a three-year follow-up period. Other unsuspecting factors, such as patients who suffer from bowel diseases, may have a higher incidence of cardiovascular disease due to an abnormal GI microbiome. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), a chronic intestinal condition, have an up to threefold higher risk for developing venous thromboembolic (VTE) complications compared to the general population. Additionally, mucin-degrading bacterial species such as Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcus are more abundant in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). As noted earlier, intestinal barrier damage can result in systemic bacterial translocation, releasing endotoxins into the bloodstream and triggering inflammation.

Lastly, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a growing global health concern characterized by the accumulation of fat in the liver in the absence of excessive alcohol consumption, often leading to liver inflammation and potential progression to more severe liver conditions. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most frequent chronic liver disease worldwide. This condition is characterized by the accumulation of excessive fat in the liver cells, a process that disrupts normal liver function and can lead to further complications. NAFLD is most commonly observed in individuals who are overweight or obese, as excess body fat contributes to fat deposition in the liver. Moreover, individuals with type 2 diabetes (T2D) are at a high risk of developing NAFLD. You are more likely to have NAFLD if you have obesity and T2D, with NAFLD occurring in nearly 9 out of 10 (90%) people living with obesity (depending on the severity of the excess body weight) and in 5–7 out of 10 (50–70%) people living with T2D (in relation to being overweight and having poor metabolic control, or if you have high lipid or LDL cholesterol levels in the blood). The estimated global incidence of NAFLD is 47 cases per 1,000 population and is higher among males than females. The estimated global prevalence of NAFLD among adults is 32% and is higher among males (40%) than females (26%). The global prevalence of NAFLD has increased over time, from 26% in studies from 2005 or earlier to 38% in studies from 2016 or beyond.

The gut-liver axis is the mutual communication between the intestine and the liver. Portal circulation, the bile tract, and systematic circulation connect this axis. In the liver, bacteria stimulate hepatic immune cells, activate inflammation pathways, and eventually proceed to NAFLD/NAFLD-HCC. In Europe, compared with healthy subjects, NAFLD patients have a high abundance of Bradyrhizobium, Anaerococcus, Peptoniphilus, Propionibacterium acnes, Dorea, and Ruminococcus, with a low abundance of Oscillospira and Rikenellaceae. More interestingly, the microbiota dysbiosis types of NAFLD patients depend on various areas and sex. In a Chinese cohort, the genera Lactobacillus, Oscillibacter, and Ruminiclostridium decrease in obese NAFLD patients. At the same time, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii was the only species that presented a different abundance between those with and without NAFLD. For the women cohort, the abundance of several other genera, such as Subdoligranulum, Coprococcus, and Coprobacter, were negatively correlated with hepatic steatosis. Improving the gut–liver axis can protect the liver from the pathogenic components in the intestine.

The Western Diet and Gut Health

The Westernized diet is a highly inflammatory diet consisting mainly of ultra-processed foods (UPFs). It has been increasingly linked to adverse health outcomes, including chronic inflammation, metabolic disorders, and impaired gut health. UPFs are industrially processed foods and are often pre-packaged, convenient, energy-dense, and nutrient-poor. UPFs are widespread in the current Western diet, and their proposed contribution to non-communicable diseases such as obesity and cardiovascular disease is supported by numerous studies. Westernized diets are characterized by a high content of unhealthy fats, refined grains, sugar, salt, alcohol, and other harmful elements, along with a reduced consumption of fruits and vegetables. This leads to critical changes in gut microbiota and the immune system, negatively affecting the gut integrity and thus promoting local and systemic chronic inflammation. The Westernized diet represents a global concern and is responsible for the obesity pandemic and NCDs, including cancer, CVDs, osteoporosis, autoimmune diseases, and T2DM, among others.

Pre-packaged processed foods are convenient in that they reduce the time required for cooking, are cost-effective, and are generally enjoyable to consume. As mentioned, these foods are often nutritionally imbalanced, containing high levels of inflammatory foods such as added sugars, unhealthy fats, and artificial additives while low in essential nutrients like fiber, vitamins, and minerals, which are vital for overall health and well-being.

Sugar consumption has become dominant in the Western diet. In 2008 and 2012, adults in the United States consumed more than 28 kg of added sugar. The average sugar consumption in 2008 was 76.7 g (19 teaspoons), and in 2012, it was 77 g per day. The average daily intake of added sugars to food in 2017–2018 was 17 teaspoons per day for children and adults in the USA. In particular, men consume 20% more teaspoons of added sugar than women. Clinical trials and epidemiologic studies have shown that individuals who consume more significant amounts of added sugar, especially sugar-sweetened beverages, tend to gain more weight and have a higher risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease.

The consumption of fructose is high in Western diets, mainly due to consuming refined or processed sugars, such as HFCS. In the United States, HFCS is found in nearly all processed foods that contain sweeteners. HFCS—due to its low cost of production—replaced sucrose as a sweetener. In the 1970s, a manufacturing breakthrough occurred in the sugar industry. High-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), containing 15% fructose, was developed through an enzyme reaction in which glucose isomerase converts glucose into fructose. In the 1980s, HFCS containing 55% fructose, a similar ratio of glucose and fructose to sucrose, was produced and widely used for beverages. Since the 1980s, the number of Overweight and obese people has increased significantly. Currently, approximately 35% of Americans are classified as obese or overweight. From the 1970s to 2000s, the average American’s annual intake of HFCS increased tremendously from 0.23 kg to 28.4 kg, while intake of sucrose moderately decreased from 46.4 kg to 30.5 kg. Daily fructose consumption increased by 26%, from 64 g/day in the 1970s to 81 g/day in the 2000s. Excessive fructose consumption, particularly from sources like HFCS, has been implicated in the rise of overweight and obese individuals, promoting insulin resistance, altering lipid metabolism, and increasing fat accumulation in the liver, further exacerbating the risk of metabolic syndrome and associated chronic diseases.

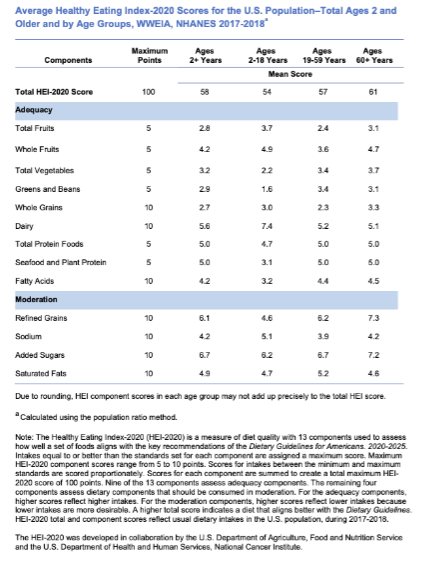

| Population Age Group | Total HEI-2020 Score | Component Scores |

|---|---|---|

| 2 years and older | 58 | Varies |

| Toddlers (12-23 months) | 63 | Varies |

The Healthy Eating Index (HEI) is designed to provide a data-driven understanding of diet quality. The HEI-2020 and the HEI-Toddlers-2020 can be used to assess how well the diets of the United States population align with the dietary patterns and critical recommendations published in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. Nationally representative survey data called What We Eat in America (WWEIA), the dietary intake interview component of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), in which Americans report the types and quantities of foods and beverages they consume in 24 hours. These nationally representative dietary intake data are used to calculate average HEI-Toddlers-2020 scores for the population ages 12 through 23 months and average HEI-2020 scores for those ages 2 years and older. The HEI-Toddlers-2020 considers the unique guidance specific to young children ages 12 through 23 months. An ideal overall HEI score of 100 suggests that the reported food set aligns with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (Dietary Guidelines) key recommendations. The average HEI-Toddlers-2020 score is 63 out of 100 (Lerman et al., 2023). The average HEI-2020 score in the U.S. population ages two and older is 58 out of 100 (Shams-White et al., 2023). A comparison of HEI scores by looking at various age categories showed that HEI-2020 scores varied by age group. Young children up to age 4 years and adults 60 and older have the highest average total HEI scores. However, average HEI-Toddlers-2020 and HEI-2020 scores indicate that average diet quality across the life span does not align with the Dietary Guidelines.

The Western diet is characterized by increased additives, such as emulsifiers, salt, and sugar, to make them more durable and hyper-palatable. High sugar consumption can have direct effects on host organs, such as in models of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, where excess dietary fructose leads to exacerbated hepatosteatosis. Understanding the immune implications, sugar plays a dual role. Sugar is an essential direct modifier of the immune response. For example, glucose is the preferred fuel source for Type 1 immunity because it is critical to the differentiation, proliferation, and function of Th1 CD4+ T cells, neutrophils, pro-inflammatory macrophages, and activated dendritic cells. Glucose is also the preferred substrate for proliferating CD8+ T lymphocytes that need to use glycolysis so that components of the tricarboxylic acid cycle can be used for translation. These pathways highlight sugar’s intricate involvement in immune cell metabolism. Another issue that compounds the effects of sugar consumption is that processed foods often contain “acellular” sugar that, unlike sugar in fruits and vegetables, does not need to be digested and is immediately available to the host and microbiota. This rapid availability of acellular sugars not only alters metabolic pathways but also contributes to the overactivation of immune and inflammatory responses, potentially exacerbating conditions such as obesity, diabetes, and autoimmune disorders.

The Western diet, rich in processed and refined foods, not only drives inflammation through excessive sugar and fat intake but also contributes to micronutrient deficiencies. This lack of essential vitamins and minerals impairs the body’s ability to regulate immune responses and mitigate oxidative stress, further perpetuating inflammatory pathways. Micronutrient (vitamins and minerals) deficits can lead to immune dysfunction. For example, the intestine absorbs Vitamin A from fruits and vegetables in the diet and then is enzymatically converted to retinoic acid (RA), a critical signal for multiple immune processes. Vitamin A deficiency can lead to immune dysfunction and increased susceptibility to infection. Iron deficiency is the most common micronutrient deficiency in the world, affecting more than 25% of people globally. Iron is essential for differentiating monocytes into macrophages. It is pivotal in enabling macrophages to combat intracellular bacteria effectively through NADPH-mediated oxidative bursts, making it critical for innate immune defenses against bacterial infections. This underscores the profound impact of the Western diet on immune functionality, illustrating how its inflammatory and nutrient-deficient profile undermines critical biological processes.

Favorable Gut Health Dietary Patterns

Dietary approaches that modulate gut microbial communities’ composition and metabolic function offer a promising strategy to improve health and prevent or treat various diseases. The Pro Gut diet promotes gut health by including foods that support a balanced and diverse gut microbiota, aiming to enhance digestive function, reduce inflammation, and prevent or manage gastrointestinal disorders. Research suggests key components include prebiotic-rich foods, such as whole grains (oats, barley), fruits (apples, bananas), vegetables (garlic, onions), and legumes (beans, lentils), which provide fiber and nutrients that feed beneficial bacteria and produce SCFAs. Probiotic-rich foods like yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, kimchi, and kombucha supply live beneficial bacteria to support gut health further. Polyphenol-rich foods, including berries, green tea, and dark chocolate, encourage the growth of good microbes. Furthermore, healthy Fats like omega-3 fatty acids in foods like fatty fish and plant-based oils can reduce gut inflammation and support the integrity of the gut lining. Dietary fiber is the key nutrient for maintaining the diversity of gut microbiota. Dietary fiber is classified into different types based on chemical structures, including resistant starches (RS), nondigestible oligosaccharides, nondigestible polysaccharides, and chemically synthesized carbohydrates. Nondigestible polysaccharides include cellulose, hemicellulose, polyfructoses, gums and mucilages, and pectins. Most dietary fibers are fermentable. Several terms are used to define subsets of dietary fiber with respect to their effects on the modulation of the gut microbiome. “Prebiotics” refers to a nondigestible food ingredient that beneficially affects the host by selectively stimulating the growth and/or activity of one or a limited number of bacteria already resident in the colon, and thus helps to improve host health. Although dietary fibers are found in many plant-based foods such as cereals, legumes, nuts, tubers, vegetables, and fruits, fiber intake is far below the recommended levels in Western countries. A low-fiber, high-fat, high-protein diet is a primary contributing factor to the depletion of fiber-degrading microbes in populations in industrialized countries. Low fiber intake reduces the production of Short-chain fatty acids and shifts the gastrointestinal microbiota metabolism to use less favorable nutrients, producing potentially detrimental metabolites.

Dietary fats are an essential energy source for the body and a fundamental part of the structure of immune cells, therefore playing a key role in modulating the immune response in health and disease. Dietary fats may also contribute to the levels and composition of adipose tissue. Indeed, increased adipose tissue contributes to low-grade inflammation characterized by enhanced secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines. An imbalance between saturated and unsaturated (omega-6 and omega-3) fatty acids significantly affects immune homeostasis. It has been associated with an increased risk of developing atherosclerosis, coronary heart disease, obesity, and metabolic syndrome. Saturated fatty acids promote an inflammatory response by activating Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and promoting pro-inflammatory cytokine production. Conversely, omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFA) obtained from fish and plant-based dietary sources have anti-inflammatory effects. A sizeable European cohort study found a significant correlation between dietary linoleic acid (n-6 PUFA) intake and the development of ulcerative colitis. In contrast, dietary intake of the shorter chain n-3 PUFA DHA was found to be protective against developing ulcerative colitis. Studies suggest that a reduced omega 6:omega 3 ratio is associated with an attenuated inflammatory response and reduced release of IL-6. This may be impaired in those carrying single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in genes involved in PUFA metabolism.

Several communities have started using probiotic-rich fermented foods as therapy. Lactic acid bacteria and Bifidobacteria are the most common probiotic microbes, while specific yeasts and bacilli may also benefit the host. Probiotics can be found in the form of yogurt, kefir, kombucha, tablets, capsules, etc. Probiotic bacteria have been shown to boost the humoral immune response by increasing the numbers of IgM-, IgG-, and IgA-secreting cells. Probiotics have become quite accessible to the public, as one can find a source in most supermarkets, pharmacies, and supplement stores. However, the actual definition of probiotics has fallen victim to commercial marketing strategies and thus become diluted. Although probiotics are widely recognized for their potential to enhance gut health by balancing the microbiome, careful consideration is crucial before supplementation. Conducting a GI map or stool analysis can identify specific bacterial imbalances, as excessive levels of certain bacteria may worsen gut dysbiosis or trigger inflammation. Supplementing with probiotics through fermented foods like yogurt, kefir, and kimchi is often more effective and sustainable, as these provide a natural blend of beneficial bacteria in a bioavailable form, reducing the risk of over-supplementation.

The Mediterranean diet is often considered the gold standard for healthy eating as it is rich in antioxidants and anti-inflammatory components. The Mediterranean diet is mainly plant-based, rich in fruits, vegetables, legumes, and nuts, associated with a moderate consumption of fish and dairy products and a low consumption of red meat and red wine. This diet has been extensively studied and linked to numerous health benefits, including improved cardiovascular health, better metabolic function, and enhanced gut health. The Mediterranean diet consists of many components rich in mono-unsaturated fatty acids such as oleic acid, in olive oil, omega-3-polyunsaturated fatty acids, such as alpha-linolenic acid in tree nuts, like walnuts, high amounts of flavonoids and antioxidants found in fruits and vegetables and high amounts of dietary fibers that have a significant impact on the composition of gut microbiota. These foods have beneficial health effects and have been referred to as functional foods. This diet contains biologically active nutrients, such as polyphenols, which significantly impact the prevention and management of chronic non-communicable diseases due to their beneficial anti-oxidative, anti-bacterial, or anti-inflammatory effects. Moreover, healthy nutrition may modify the risk for neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease or Parkinson’s disease or even protect against depression and psychosocial maladjustment. There is a lot of evidence highlighting the impact of healthy nutrition for women on the composition of gut microbiota and the metabolic health of their offspring. It may further protect the offspring from congenital malformations or even adverse neurodevelopment.

Discussion and Implications for Practice

The gut microbiota, the body’s largest symbiotic ecosystem, is crucial in maintaining human health and intestinal balance. Dysbiosis, defined by reduced microbial diversity or an imbalance of harmful and beneficial microbes, is linked to various conditions, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), diabetes, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), cardiovascular diseases, and mental health disorders. Nutrition significantly influences the composition and function of the microbiota, with dietary nutrients fueling microbial growth and metabolites maintaining intestinal health, emphasizing the importance of informed dietary choices in promoting a balanced microbiome. Healthcare practitioners should consider personalized nutritional interventions, such as tailoring nutrition plans to individual patient needs to address dysbiosis effectively. Regular physical activity, adequate sleep, and stress management can positively influence the gut microbiota, supporting gut homeostasis and overall health. Being mindful of medications that can disrupt gut bacteria, such as antibiotics, is essential; healthcare providers should weigh the benefits and potential impacts on gut health when prescribing these medications. Educating patients about the significance of gut health and its impact on overall well-being empowers them to make informed dietary and lifestyle choices that support a balanced microbiome. By integrating these strategies into clinical practice, healthcare professionals can be pivotal in promoting gut health, potentially reducing the risk of chronic diseases and poor immune and mental health associated with dysbiosis.

The authors have no sources of funding to disclose.

References

2. Acevedo-Román, A., Pagán-Zayas, N., Velázquez-Rivera, L. I., Torres-Ventura, A. C., & Godoy-Vitorino, F. (2024). Insights into gut dysbiosis: Inflammatory diseases, obesity, and restoration approaches. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(17), 9715. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25179715

3. Toor, D., Wsson, M. K., Kumar, P., Karthikeyan, G., Kaushik, N. K., Goel, C., Singh, S., Kumar, A., & Prakash, H. (2019). Dysbiosis disrupts gut immune homeostasis and promotes gastric diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(10), 2432. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20102432

4. Zhao, M., Chu, J., Feng, S., Guo, C., Xue, B., He, K., & Li, L. (2023). Immunological mechanisms of inflammatory diseases caused by gut microbiota dysbiosis: A Review. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, p. 164, 114985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114985

5. Weiss, G. A., & Hennet, T. (2017). Mechanisms and consequences of intestinal dysbiosis. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 74(16), 2959–2977. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-017-2509-x

6. Bustamante, J.-M., Dawson, T., Loeffler, C., Marfori, Z., Marchesi, J. R., Mullish, B. H., Thompson, C. C., Crandall, K. A., Rahnavard, A., Allegretti, J. R., & Cummings, B. P. (2022b). Impact of fecal microbiota transplantation on gut bacterial bile acid metabolism in humans. Nutrients, 14(24), 5200. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14245200

7. Sah, D. K., Arjunan, A., Park, S. Y., & Jung, Y. D. (2022). Bile acids and microbes in metabolic disease. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 28(48), 6846–6866. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v28.i48.6846

8. Martin-Gallausiaux, C., Marinelli, L., Blottière, H. M., Larraufie, P., & Lapaque, N. (2020). SCFA: Mechanisms and functional importance in the gut. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 80(1), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0029665120006916

9. Carpenter, L. C., Pérez-Verdugo, F., & Banerjee, S. (2023). Mechanical Control of Cell Proliferation Patterns in Growing Tissues. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.25.550581

10. NCI Dictionary of Cancer terms. Comprehensive Cancer Information – NCI. (n.d.). https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/cell-differentiation

11. Wiertsema, S. P., van Bergenhenegouwen, J., Garssen, J., & Knippels, L. M. (2021). The interplay between the gut microbiome and the immune system in the context of infectious diseases throughout life and the role of Nutrition in Optimizing Treatment Strategies. Nutrients, 13(3), 886. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030886

12. Shi, N., Li, N., Duan, X., & Niu, H. (2017). Interaction between the gut microbiome and mucosal immune system. Military Medical Research, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-017-0122-9

13. Takiishi, T., Fenero, C. I., & Câmara, N. O. (2017). Intestinal barrier and gut microbiota: Shaping our immune responses throughout life. Tissue Barriers, 5(4). https://doi.org/10.1080/21688370.2017.1373208

14. Kain, T., Dionne, J. C., & Marshall, J. C. (2024). Critical illness and the gut microbiome. Intensive Care Medicine, 50(10), 1692–1694. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-024-07513-5

15. Dickson, R. P. (2016). The microbiome and critical illness. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 4(1), 59–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-2600(15)00427-0

16. Du, Y., He, C., An, Y., Huang, Y., Zhang, H., Fu, W., Wang, M., Shan, Z., Xie, J., Yang, Y., & Zhao, B. (2024). The role of short chain fatty acids in inflammation and body health. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(13), 7379. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25137379

17. Limbana, T., Khan, F., & Eskander, N. (2020a). Gut microbiome and depression: How microbes affect the way we think. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.9966

18. Childs, C. E., Calder, P. C., & Miles, E. A. (2019). Diet and immune function. Nutrients, 11(8), 1933. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081933

19. Sung, J., Rajendraprasad, S. S., Philbrick, K. L., Bauer, B. A., Gajic, O., Shah, A., Laudanski, K., Bakken, J. S., Skalski, J., & Karnatovskaia, L. V. (2024). The human gut microbiome in critical illness: Disruptions, consequences, and therapeutic frontiers. Journal of Critical Care, 79, 154436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2023.154436

20. Xiong, R.-G., Li, J., Cheng, J., Zhou, D.-D., Wu, S.-X., Huang, S.-Y., Saimaiti, A., Yang, Z.-J., Gan, R.-Y., & Li, H.-B. (2023). The role of gut microbiota in anxiety, depression, and other mental disorders as well as the protective effects of dietary components. Nutrients, 15(14), 3258. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15143258

21. Zhou, Z., Sun, B., Yu, D., & Zhu, C. (2022a). Gut microbiota: An important player in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.834485

22. Magne, F., Gotteland, M., Gauthier, L., Zazueta, A., Pesoa, S., Navarrete, P., & Balamurugan, R. (2020). The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio: A relevant marker of gut dysbiosis in obese patients? Nutrients, 12(5), 1474. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12051474

23. Bielka, W., Przezak, A., & Pawlik, A. (2022). The role of the gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of diabetes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(1), 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23010480

24. Diabetes statistics. DRIF. (2023, October 10). https://diabetesresearch.org/diabetes-statistics/?gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQiAire5BhCNARIsAM53K1j5J7kBkpvi3V2PNdn4LjETFZnU3jwJLicfGGs7mdIyZeAu5g3IzCQaAqxKEALw_wcB

25. Iatcu, C. O., Steen, A., & Covasa, M. (2021). Gut microbiota and complications of type-2 diabetes. Nutrients, 14(1), 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14010166

26. Wang, L., Alammar, N., Singh, R., Nanavati, J., Song, Y., Chaudhary, R., & Mullin, G. E. (2020). Gut microbial dysbiosis in the irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 120(4), 565–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2019.05.015

27. Sugihara, K., & Kamada, N. (2021). Diet–microbiota interactions in inflammatory bowel disease. Nutrients, 13(5), 1533. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13051533

28. Mentella, M. C., Scaldaferri, F., Pizzoferrato, M., Gasbarrini, A., & Miggiano, G. A. (2020). Nutrition, IBD and Gut Microbiota: A Review. Nutrients, 12(4), 944. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12040944

29. Astudillo, A. A., & Mayrovitz, H. N. (2021). The gut microbiome and cardiovascular disease. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.14519

30. Reis, F. (2023). Gut microbiota dysbiosis and cardiovascular disease – the chicken and the Egg. Revista Portuguesa de Cardiologia, 42(6), 553–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.repc.2023.03.004

31. Teng, M. L., Ng, C. H., Huang, D. Q., Chan, K. E., Tan, D. J., Lim, W. H., Yang, J. D., Tan, E., & Muthiah, M. D. (2023). Global incidence and prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clinical and Molecular Hepatology, 29(Suppl). https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2022.0365

32. Francque, S. M., Marchesini, G., Kautz, A., Walmsley, M., Dorner, R., Lazarus, J. V., Zelber-Sagi, S., Hallsworth, K., Busetto, L., Frühbeck, G., Dicker, D., Woodward, E., Korenjak, M., Willemse, J., Koek, G. H., Vinker, S., Ungan, M., Mendive, J. M., & Lionis, C. (2021). Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A patient guideline. JHEP Reports, 3(5), 100322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2021.100322

33. Song, Q., & Zhang, X. (2022). The role of gut–liver axis in gut microbiome dysbiosis associated NAFLD and NAFLD-HCC. Biomedicines, 10(3), 524. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10030524

34. Brichacek, A. L., Florkowski, M., Abiona, E., & Frank, K. M. (2024a). Ultra-processed foods: A narrative review of the impact on the human gut microbiome and variations in classification methods. Nutrients, 16(11), 1738. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111738

35. García-Montero, C., Fraile-Martínez, O., Gómez-Lahoz, A. M., Pekarek, L., Castellanos, A. J., Noguerales-Fraguas, F., Coca, S., Guijarro, L. G., García-Honduvilla, N., Asúnsolo, A., Sanchez-Trujillo, L., Lahera, G., Bujan, J., Monserrat, J., Álvarez-Mon, M., Álvarez-Mon, M. A., & Ortega, M. A. (2021). Nutritional components in Western diet versus Mediterranean diet at the gut microbiota–immune system interplay. Implications for health and disease. Nutrients, 13(2), 699. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020699

36. Witek, K., Wydra, K., & Filip, M. (2022). A high-sugar diet consumption, metabolism and health impacts with a focus on the development of substance use disorder: A narrative review. Nutrients, 14(14), 2940. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14142940

37. Jung, S., Bae, H., Song, W.-S., & Jang, C. (2022). Dietary fructose and fructose-induced pathologies. Annual Review of Nutrition, 42(1), 45–66. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nutr-062220-025831

38. Burr, A. H., Bhattacharjee, A., & Hand, T. W. (2020). Nutritional modulation of the microbiome and immune response. The Journal of Immunology, 205(6), 1479–1487. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.2000419

39. Zhao, M., Chu, J., Feng, S., Guo, C., Xue, B., He, K., & Li, L. (2023). Immunological mechanisms of inflammatory diseases caused by gut microbiota dysbiosis: A Review. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 164, 114985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114985

40. Valdes, A. M., Walter, J., Segal, E., & Spector, T. D. (2018). Role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2179

41. Gill, P. A., Inniss, S., Kumagai, T., Rahman, F. Z., & Smith, A. M. (2022). The role of diet and gut microbiota in regulating gastrointestinal and inflammatory disease. Frontiers in Immunology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.866059

42. Kopacz, K., & Phadtare, S. (2022). Probiotics for the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Healthcare, 10(8), 1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10081450

43. Gantenbein, K. V., & Kanaka-Gantenbein, C. (2021). Mediterranean diet as an antioxidant: The impact on metabolic health and overall wellbeing. Nutrients, 13(6), 1951. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13061951 – formerly 44