Genetic Risk Factors and Personalized Osteoporosis Treatments

OSTEOPOROSIS: Genetic Risk Factors in the New Therapies. Challenges for Personalized Treatments

Alejandra Villagomez-Vega 1,3; Ismael Nuño-Arana 2,3

- Alejandra Villagomez-Vega Departamento de Ciencias Biomédicas; Centro de Investigaciones Multidisciplinarias en Salud, Centro Universitario de Tonalá. Universidad de Guadalajara. México.

- Ismael Nuño-Arana Departamento de Salud-Enfermedad como proceso Individual; Centro de Investigaciones Multidisciplinarias en Salud, Centro Universitario de Tonalá. Universidad de Guadalajara. México.

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 April 2025

CITATION: VILLAGOMEZ-VEGA, Alejandra; NUÑO-ARANA, Ismael. OSTEOPOROSIS: Genetic Risk Factors in the New Therapies. Challenges for Personalized Treatments. Medical Research Archives, [S.l.], v. 13, n. 4, apr. 2025. Available at: <https://esmed.org/MRA/mra/article/view/6413>.

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i4.6413

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

The word osteoporosis means “porous bone” a disease that is defined as a skeletal disorder characterized by alterations in its microarchitecture making the bones more porous and less dense, leading to a decrease in bone strength, generating a greater risk of fractures.

It is a disease considered among the greatest public health problems in the elderly population worldwide, affecting women to a greater extent; around a third of women suffer from osteoporosis and one in eight men over 50 years of age.

Known as a silent disease because significant signs do not appear before fractures appear, so in most cases, people realize they have osteoporosis until they suffer a fracture. Osteoporotic fractures have various risk factors, from low physical activity, smoking, and the use of certain drugs, as well as genetic variations that have been associated with diverse types of fractures.

There is a considerable group of drugs to treat the disease, however, management is only focused on monotherapy according to the quantitative value of a phenotype (BMD) bone mineral density. It has never focused on individual pathophysiology, since it was unknown. The main treatment guidelines for osteoporosis include a bisphosphonate and it is maintained for years depending on response, in addition to lifestyle and dietary recommendations. However, a controversial aspect is the low response to treatment, which is accompanied by poor adherence to treatments.

The new drugs that have more intense and prolonged effects are expensive and are not available in most countries. Much progress has been made in terms of knowledge of the factors that contribute to the development of this and other pathologies. Diversity of variations in the genome has been implicated both in the development of the disease and in the response to pharmacological treatments.

Many of these variations in the genome and its expression represent part of the genetic factors that contribute to the development of the disease. They are now important biomarkers that allow us to better understand and develop more specific drugs or individualized schemes with those already existing. There are already various scores and indications of first guidelines on how to quantify these factors, such as the Polygenic Risk Score (PRS) or Mendelian Randomization (MR). However, there is still a need to analyze and expand the perspectives of how the factors involved interact without being specifically additive/summative, and the difficulties that this face have already been observed.

The aims of this brief review are to discuss shortly the actual drugs approved for osteoporosis by the main treatment guidelines. The advances in molecular biology studies that support the importance of genetic factors in risk and response to osteoporosis treatment.

And finally, how the experts will face these advances to expand and personalized the treatments to be more efficient and successful.

Keywords

Osteoporosis, Risk Factors, Classic and New Treatments, Challenges in Treatments

Introduction

The word osteoporosis means “porous bone” a disease that is defined as a skeletal disorder characterized by alterations in its microarchitecture causing the bones to become more porous and less dense, leading to a decrease in bone strength, generating a greater risk of fractures.

It is a disease considered among the greatest public health problems in the elderly population worldwide, affecting around 10% of the world’s population and more than 30% of postmenopausal women over 50 years of age suffer from osteoporosis. Due to the longer life expectancy in many countries, it will become one of the most prevalent diseases in aging societies. In addition to being expensive and prolonged treatments in developing countries with population changes that cannot sustain the management of so many patients, it will be crucial to identify at-risk populations and change management strategies; otherwise, they could lead to the collapse of their health systems or they would not be able to provide full coverage for many diseases that are becoming increasingly challenging to address.

Known as the silent disease because most people only realize they have osteoporosis when they suffer a fracture. A fracture causes pain and, more importantly, disability due to the physical deformity. In addition, an osteoporotic bone is more difficult and takes longer to heal. Hip fractures can be devastating, contributing to up to 5% of mortality in men and women. Osteoporotic fractures have various risk factors, such as low physical activity, smoking, the use of certain drugs, and some genetic variations associated with some types of fractures.

There are already indications of generating value and using multiple biomarkers that have been associated with the risk, progression, and evolution of the disease to initiate personalized management. However, there is still a need to understand their role and influence on the bone phenotype in more depth. The advances are promising, but there are still many challenges for all the sectors involved to agree on and homogenize all the criteria and factors for their use in treatment. Adding to the factor that requires its potential near use is the high number of patients who do not respond to conventional therapies with bisphosphonates, the most commonly used drugs, due to their side effects and consequent lack of adherence to management, which increases the poor response.

It is then that management guidelines based on antiresorptive monotherapies will have the enormous challenge of incorporating all the advances in the pathophysiology of the disease to apply them to management and help increase the efficacy and therapeutic response.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF OSTEOPOROSIS

Osteoporosis is classified as primary and secondary depending on the causes; primary osteoporosis, postmenopausal or senile and secondary osteoporosis, induced by drugs or other diseases such as diabetes or autoimmune diseases.

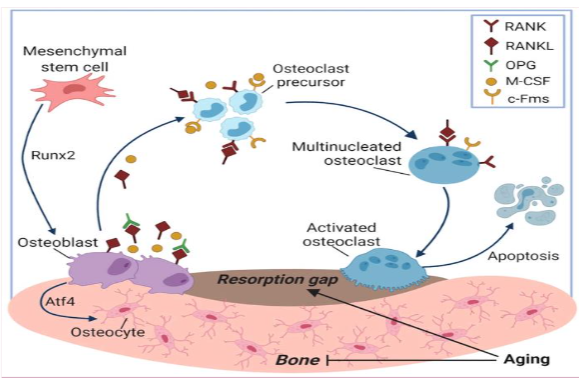

Bone is a very dynamic tissue that is constantly remodeling throughout life. There is a process of bone resorption followed by a formation stage, three types of cells are essential in this process: osteoblasts, which are responsible for the formation of new bone, specialized macrophages known as osteoclasts, which are responsible for the resorption process, osteoblasts cells responsible for the bone formation process and osteocytes responsible for starting this process when detecting damage to the bone, they regulate the expression of the macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) and nuclear activator factor κβ ligand (RANKL), factors that help the recruitment and activation of osteoclasts.

This cycle maintains a balance between both phases, bone resorption and formation. However, once this balance is broken, especially when the formation process is reduced, BMD decreases causing osteoporosis.

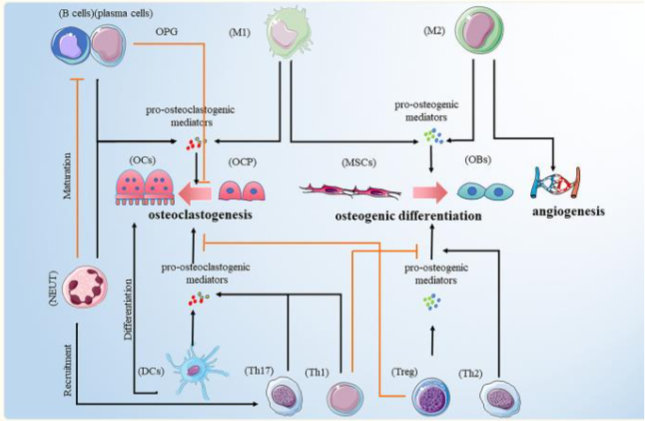

The common development of bone and immune tissues makes them function as a unit, due to the links that exist between them. The study of how they interact and how the functioning of both systems is affected has been studied for decades and is known as osteoimmunology. Since 1970, some reports began to emerge suggesting that bone loss was related to some active cells of the immune system. Horton et al. reported a case of periodontitis characterized by infiltration of periodontal tissues that generated alveolar bone resorption and tooth loss. They found in cultures of these tissues an osteoclastogenic substance called osteoclast activating factor (OAF) that stimulated bone resorption, leading to bone loss.

The imbalance of the immune system has been linked to various bone problems in which the modulation of its metabolism is affected since it regulates the activation of key cells in bone remodeling or through the induction of factors that regulate said metabolism.

There is a close relationship between bone marrow (BM) and bone cells, of which BM lymphocytes and a T cell component act in the regulation of bone remodeling. T cells are divided into CD4+ T cell and CD8+ T cell populations. CD4+ cells can differentiate into Th1, Th2, Th9, Th17, Th22, regulatory T (Treg), and follicular helper T (TFH) depending on the stimulus. The main function of Th17 cells is the activation of osteoclastogenesis, unlike Treg cells, whose main function is the inhibition of bone resorption.

However, CD8+ T cells also function as bone protectors, by stimulating the production of a soluble factor, osteoprotegerin, which inhibits osteoclastogenesis, in addition to activating the Wnt pathway, which functions as a stimulator of osteoblastogenesis.

Several conditions and factors can precipitate such imbalance and increase the risk of developing osteoporosis, such as advanced age, genetics, sex steroid deficiency, lack of physical activity, dietary factors such as calcium and vitamin D deficiency, smoking and excessive alcohol consumption. Decreased estrogen levels in postmenopausal women are one of the most important factors in the development of osteoporosis since estrogens are the main ones that promote bone formation and their absence is the main trigger for increased bone resorption.

RISK FACTORS

Osteoporosis is a complex or multifactorial disease; the combination and interaction of various factors are responsible for triggering the disease. A high content of these factors is genetic, in people with a family history of the disease, heritability has been estimated between 50-85%, so they have a higher risk of developing it.

Susceptibility to osteoporosis is the result of many genetic variations that determine 60 to 80% of bone loss and their interaction with environmental factors such as those mentioned above. Therefore, even with a balanced diet with an adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D, if genetic factors are present, the development of the disease is more likely.

GENETIC FACTORS

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have been of great help in identifying genetic variants in complex diseases. There are several GWAS in osteoporosis in which it has been determined that single nucleotide variants (SNPs) are the main genetic factors that contribute to the risk of suffering from it. To date 1103 SNPs have been associated with decreased BMD, in 515 loci, these SNPs explained a total variance of 20.3% in BMD. These variants are found in genes responsible for bone remodeling; genes that code for factors or cytokines that help modulate their metabolism.

Among the main genes associated with osteoporosis are: COL1A1, the main organic component, osteocalcin, and sclerostin, among others Bone Matrix Proteins (BMP), which are part of the structural pathway. Of those that stimulate formation, mainly the estrogen receptor (ESRα). Another important gene is the one that encodes the aromatase enzyme (CYP19A1), responsible for the synthesis of estrogens; in addition to proteins responsible for transport and metabolism. SNPs in the osteoprotegerin gene as one of the most important regulators to stop resorption, where in addition to associating it with the disease, it is highly predictive of fractures. Among other important ones is the calcitonin receptor, a hormone responsible for stopping osteoclastogenesis, in some cytokines that stimulate formation such as transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) and Wnt, and some hormones such as vitamin D and its receptors that also promote bone formation.

In the osteoclastogenic pathway, variants have been found in genes that code for important proteins in the inflammatory response such as TNF, RANK, RANKL, and some inflammatory pro-activators such as IL-6, where a variant has been found that is highly associated with osteoporosis, and that even influences the response to drugs. as the same IL-1 and IL-10 among others. One of the most important pathways still under study is the Parathyroid hormone gene and its receptors.

Being a highly polygenic disease, all these variations alter the bone remodeling process, leading to a decrease in formation or an increase in resorption, which can trigger the disease. These DNA variants have a small impact on their own and, although it is important to know the mechanism of each one separately, most patients do not have just one, there can be hundreds, and this can increase the effect when combined, enhancing their physiological effect. In polygenic disorders, one variant is not informative for assessing osteoporosis risk, the genetic load conferred by the combination of all the variants that a person has can provide information to detect people at higher risk of developing osteoporosis.

Researchers believe that there may be a measure that assesses this risk, through a polygenic risk score, where a weighted sum is given according to the number of loci present.

The definition of an osteogenomic profile, generated from the combination of several SNPs associated with osteoporosis, has been proposed. Ho-Le et al. generated osteogenic profiles from 62 genetic variants associated with BMD and demonstrated the association of the profile with the rate of bone loss. The rate of longitudinal bone loss (ΔBMD) is considered a risk factor for fracture and this variation is determined by genetic factors. They constructed weighted genetic risk scores (GRS) by summing all the risk alleles for each individual, so each individual had a GRS. Each unit increase in the GRS was associated with a 41% chance of faster bone loss, however, this association was only in women.

Genetic factors also increase the risk of fracture. Women with a family history of hip fracture are twice as likely to suffer from it. Fracture risk is determined by several factors, in addition to genetic factors, such as low BMD, a history of fractures and falls, prolonged use of certain drugs such as glucocorticoids, smoking, and alcoholism. Some predictive models help us estimate the probability of fractures, such as the FRAX and QFract programs, so they have deficiencies since they do not take genetic factors into account, and having a high hereditary component may be the main reason why these predictive models are not as effective.

OSTEOPOROSIS TREATMENT

There are guidelines on each continent to describe the treatment of osteoporosis, according to the pharmacological availability of the countries that comprise it and based on the clinical results of studies carried out in hospitals of their population. The guidelines expose the entire pharmacological arsenal that is currently available, all agree on the drugs to be used and the necessary support measures.

The treatment of osteoporosis indicates general care such as a balanced diet, correcting nutritional deficiencies, particularly calcium, vitamin D, and protein, and physical activity is important as far as possible to maintain patient mobility; in addition to supplementation, alcohol and tobacco consumption should be eliminated because they decrease bone density. Something important is to emphasize to caregivers that measures should be implemented to reduce the risk of falls, all of this of course in addition to the different options of pharmacological therapies, since drugs are what will help increase BMD.

Pharmacological therapies are divided into two main types: anabolic therapies that promote bone formation and are mainly based on hormonal therapy such as estrogen, parathyroid hormone, calcitonin, however they are not indicated for everyone, and their cost can be high; and antiresorptive therapies that aim to stop bone resorption, among which are bisphosphonates, which are the first-line drugs and therefore the most widely used, and their main advantages are their low cost and their effectiveness against fractures.

The next and most novel treatments point to the use of miRNAs as potential substances with greater specificity that allow us to modulate the individualized pathways of each patient that cause their decrease in BMD, such as the Wnt4/b-catenin pathway, BMP2 or RUNX2 and 3. Even stop or modulate inflammatory responses resulting from oxidative stress and ROS that originate in a bone with multiple stimuli of proinflammatory cytokines in various pathological processes.

In addition, they would help reduce the adverse effects resulting from the particularly prolonged use of drugs. This aspect becomes important due to the economic and physical strain that patients experience during their treatment. The appearance of fractures complicates and contributes considerably to the deterioration of the overall health of the patient and his or her family.

However, this type of drug is not yet included in the main management guidelines for osteoporosis.

GUIDELINES FOR THE TREATMENT OF OSTEOPOROSIS

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) in 2020, the American Heart Association published its updated guidelines for the treatment of osteoporosis. In this standardized protocol, 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) levels are considered as part of the treatment, trying to maintain serum levels at ≥30 ng/mL in patients with osteoporosis (preferred range, 30 to 50 ng/mL). Lifestyle changes, such as limiting alcohol consumption to 2 units per day, eliminating tobacco use, and advising the patient to engage in physical activity, weight-bearing exercises, balance and resistance training, as far as possible.

Regarding drug therapy, the AACE establishes the use of drugs from osteopenia to osteoporosis, especially in patients with a history of hip or spine fracture. In patients who have a high risk of fracture, one of the most appropriate treatments for the beginning of their treatment are some bisphosphonates such as alendronate, risedronate, zoledronate, and a monoclonal antibody such as denosumab, and if oral therapy is not possible, the options are abaloparatide, romosozumab and teriparatide, if the risk of fracture is mainly in the spine, raloxifene and ibandronate have proven effective.

The UK National Osteoporosis Guideline Group (NOGG), The latest review published in 2021; guideline for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis, for decision-making on pharmacological therapy, recommends taking into account the degree of fracture risk, classifying it as low, intermediate, and high, through the use of FRAX, also recommends taking into account some important clinical factors. In patients classified as having a high risk of fracture, the use of two anabolic drugs is recommended, teriparatide and romosozumab since these drugs have shown a greater reduction in fracture risk, compared to antiresorptives. In patients with fragility due to previous fractures, studies have shown efficacy when using zoledronate, risedronate, teriparatide, and romosozumab, if you have suffered a hip fracture, the first-line treatment would be zoledronate. As a second line of treatment after the use of teriparatide or romosozumab, use bisphosphonates such as alendronate, zoledronate, or denosumab. Raloxifene may be used as a second line of treatment, especially after the use of anabolic steroids. Strontium ranelate, especially in patients in whom bisphosphonates are contraindicated or have not been well tolerated. The NOGG recommends calcium (minimum 700 mg per day) and vitamin D supplementation alongside drug therapy.

The International Osteoporosis Foundation and European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis published guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in 2013 and updated in European guidelines with systematic reviews in 2019 highlighting prevention and management with strengthening of lifestyle and dietary measures. Pharmacological management, as in the guidelines described above, is based on the availability of antiresorptives, starting with bisphosphonates, followed by others with greater stimulation such as Denosumab or Romosozumab, but according to their response, they are complemented with SERMs, mainly Raloxifene and/or hormonal, in addition to others such as Teriparatide in more severe cases.

Most guidelines describe drug therapy well, starting with fracture risk, since all guidelines consider the degree of fracture risk when deciding on the most appropriate treatment. They agree on vitamin D supplementation, and some even take calcium levels into account, as well as lifestyle, such as reducing tobacco and alcohol consumption and trying to be physically active. Even if the different guidelines have variations in the use of certain medications, they all ask for BMD monitoring, mainly by DEXA every one or two years, to determine if the therapy is working. However, no guideline considers genetic factors, although several studies have demonstrated the effect that SNPs have on the response to treatment.

PHARMACOGENETIC STUDIES

Pharmacogenetic studies have taken on great importance in different diseases, especially in complex diseases, not only try to explain their pathophysiology but also to provide information on how to contribute to the prediction of response to treatment. Some authors suggest that genetic factors represent around 15-30% of the individual response to drugs.

Xiao and his team conducted a cross-sectional study to determine genetic profiles in Caucasian women at risk for osteoporosis. They included 1200 Caucasian women. Their BMD was determined and SNPs associated with low BMD were genotyped. Multilocus genetic risk scores (GRSs) were determined for the association analysis of BMD and GRSs. Regression analysis was performed. GRSs subgroups were made according to the signaling pathways in which they are involved, one group of the Wnt pathway, and another group of the RANK/RANKL/OPG system. In the results, both GRS subgroups were associated with decreased BMD levels. According to their results, they conclude that the analyzed genetic profiles manage to demonstrate the variations in BMD.

Zhou et al published a study on the response to alendronate treatment in a Chinese population. They included 639 patients with osteoporosis and osteopenia who received alendronate 70 mg per week for 12 months. All women were supplemented with 600 mg of elemental calcium and 125 IU of vitamin D3. Only 540 patients completed treatment, mainly due to side effects of the drug. Patients were genotyped for 7 SNPs of the SOST gene, 2 of these SNPs were found to be related to the ability to respond to treatment with alendronate. They conclude that although pharmacogenetic studies are still insufficient, they are nevertheless very valuable as they help predict the effect of a drug to obtain maximum efficacy and, above all, try to reduce side effects.

In 2014, Mencej-Bedrač and her team published a cohort study that included 56 women with postmenopausal osteoporosis who were receiving treatment with raloxifene, a selective estrogen receptor modulator. These patients were followed for one year to observe changes in mineral density and to see if there were variations influence the response to treatment according to genetic variants. 11 SNPs from 6 different genes were determined: -290C > T, -643C > T, and -693G > C of the TNFSF11 gene, +34694C > T, +34901G > A, and +35966insdelC of the TNFRSF11A gene, K3N and 245T > G of the TNFRSF11B gene, A1330V in the LRP5 gene, I1062V in LRP6, and -1397 -1396insGGA in the SOST gene. Biochemical markers of bone turnover and BMD measurement were determined to determine the efficacy of raloxifene. In the results obtained, they found an association in hip BMD and 34901G>A of TNFRSF11A (p=0.040), an association was found with lumbar spine BMD and 1397 -1396insGGA of SOST (p=0.015), as for bone turnover markers, an association was found between the concentrations of collagen type I telopeptides and a SNP of TNFSF11. The conclusion they reach is that the efficacy of treatment with raloxifene is influenced by genetic variants in patients with osteoporosis, so it is important to take into account the genetic background of the patients to determine their treatments.

Marozik and his team published a study in 2019 on the effect of some genetic variants on the response to bisphosphonates. They conducted a 12-month cohort study that included 201 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis who were prescribed pharmacological therapy with bisphosphonates. They were also genotyped for some polymorphic variants in the SOST, PTH, and FGF2 genes. After one year of treatment, they were divided into 2 groups according to their response to treatment: 122 (60%) patients responded to treatment, and 79 (40%) patients did not respond to therapy. Some gene variants were found in greater proportion in the non-responder group, generated allelic combinations of the SNPs analyzed and found that carriers of the allelic combination T-T-G-C (constructed from rs1234612, rs7125774, rs2297480 and rs10925503) showed a greater predisposition to a negative response to treatment with bisphosphonates, so they conclude that genetic variants should be taken into account due to the impact and importance they have in the pharmacogenetics of treatment.

Another study that investigates the association of response to treatment with zoledronic acid and the presence of haplotypes is the one carried out by Wang and collaborators in a Chinese population, where they included 110 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis who received zoledronic acid for one year and genotyped for 13 SNPs of the NF-κB pathway (NF-κB1, NF-κB2, RELA, RELB and REL), from which different haplotypes were constructed. They found one of the haplotypes constructed with the SNPs of rs28362491, rs3774937, rs230521, rs230510 and rs4648068 in NF-κB1, the ITCTG haplotype showed a significant association with % change in BMD at L1–4 (p < 0.001). The DTCTG haplotype showed a considerable association with a % change of BMD at the femoral neck (p = 0.008). Another haplotype, the CGC haplotype of rs7119750, rs2306365, and rs11820062 in RELA showed a nominal association with a % change in BMD at total hip (p < 0.001). However, although it was associated with a % change in BMD, no haplotype was associated with treatment response.

The Polygenic Risk Score is an initial strategy that homogenously quantifies each allele by assigning a homogeneous and summative value. However, the approval of this strategy, expansion or improvement will require the multiple consensus of experts and will depend on a greater number of studies to support its application, since it does not take into account the potential aggregation or interaction between alleles. Another aspect to be further investigated is the ancestry of each population and the alleles that represent a population may differ from others. A greater number of studies are required in the various populations that are not yet genetically well characterized, such as Latin American and African populations. And to delve deeper into the role that these play in the disease. Gather the greatest amount of appropriate information to generate scores or records that allow us to have more elements or indicators to individualize treatments and increase the response to management and provide us with more efficiency and effectiveness and the objective of curing the disease in the greatest possible number of patients is met. Efficiency in management must overcome wear and tear and economic costs in order to have a much broader reach to all possible populations.

Even when patients have adequate adherence to treatment, exercise, reduce alcohol and tobacco consumption, and eat a diet supplemented with calcium and vitamin D, there is a high percentage (18-40%) of patients who do not see an increase in their bone mineral density. Failure to take genetic factors into account when deciding the most appropriate drug for each patient can determine the effectiveness of the treatment. It is difficult for guidelines to add the genetic factors since it has not yet been possible to fully determine which genetic variants contribute to the onset of the disease or the risk of fracture. To make matters even more complicated, many variants are associated but only in certain populations, so we cannot categorize which are all the SNPs involved in osteoporosis in the world population. However, the fact that the pharmacogenetics of the disease is increasingly being studied in different populations provides information so that experts can begin to include them in disease management guidelines.

Conclusion

Osteoporosis is a multifactorial disease in which genetic factors represent up to 85%. However, the main guidelines not focus in personalized the most appropriate treatment. Although there are several pharmacogenetic studies, more information is needed to know how personalized pharmacological treatments can be included in the treatment criteria. In addition to taking into account that some biomarkers may be useful in certain populations due to genomic diversity, which represents a challenge in personalized therapy for osteoporosis.

References

- Lei C, Song JH, Li S, et al. Advances in materials-based therapeutic strategies against osteoporosis. Biomaterials. 2023;296:122066. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2023.122066

- Yong EL, Logan S. Menopausal osteoporosis: screening, prevention and treatment. Singapore Med J. 2021;62(4):159-166. doi:10.11622/smedj.2021 036

- He J, Xu S, Zhang B, et al. Gut microbiota and metabolite alterations associated with reduced bone mineral density or bone metabolic indexes in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12(9):8583-8604. doi:10.18632/aging.103168

- Clynes MA, Harvey NC, Curtis EM, Fuggle NR, Dennison EM, Cooper C. The epidemiology of osteoporosis. Br Med Bull. 2020;133(1):105-117. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldaa005

- Muñoz M, Robinson K, Shibli-Rahhal A. Bone Health and Osteoporosis Prevention and Treatment. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2020;63(4):770-787. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000572

- Subarajan P, Arceo-Mendoza RM, Camacho PM. Postmenopausal Osteoporosis: A Review of Latest Guidelines. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2024;53(4):497-512. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2024.08.008

- GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017 [published correction appears in Lancet. 2019 Jun 22;393(10190):e44. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31047-5.]. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789-1858. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7

- Garnero P. Biomarkers for osteoporosis management: utility in diagnosis, fracture risk prediction and therapy monitoring. Mol Diagn Ther. 2008;12(3):157-170. doi:10.1007/BF03256280

- Migliorini F, Maffulli N, Spiezia F, Tingart M, Maria PG, Riccardo G. Biomarkers as therapy monitoring for postmenopausal osteoporosis: a systematic review. J Orthop Surg Res. 2021 May 18;16(1):318. doi: 10.1186/s13018-021-02474-7. PMID: 34006294; PMCID: PMC8130375.

- Morales-Santana S, Díez-Pérez A, Olmos JM, et al. Circulating sclerostin and estradiol levels are associated with inadequate response to bisphosphonates in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Maturitas. 2015;82(4):402-410. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.08.007

- Marozik P, Alekna V, Rudenko E, et al. Bone metabolism genes variation and response to bisphosphonate treatment in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0221511. Published 2019 Aug 22. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0221511

- Srivastava RK, Sapra L. The Rising Era of “Immunoporosis”: Role of Immune System in the Pathophysiology of Osteoporosis. J Inflamm Res. 2022;15:1667-1698. Published 2022 Mar 5. doi:10.2147/JIR.S351918

- Chen H, Senda T, Kubo KY. The osteocyte plays multiple roles in bone remodeling and mineral homeostasis. Med Mol Morphol. 2015;48(2):61-68. doi:10.1007/s00795-015-0099-y

- Nakashima T. Clin Calcium. 2015;25(1):21-28.

- Siddiqui JA, Partridge NC. Physiological Bone Remodeling: Systemic Regulation and Growth Factor Involvement. Physiology (Bethesda). 2016;31(3):233-245. doi:10.1152/physiol.00061.2014

- Weitzmann MN. Bone and the Immune System. Toxicol Pathol. 2017;45(7):911-924. doi:10.1177/0192623317735316

- Horton JE, Raisz LG, Simmons HA, Oppenheim JJ, Mergenhagen SE. Bone resorbing activity in supernatant fluid from cultured human peripheral blood leukocytes. Science. 1972;177(4051):793-795. doi:10.1126/science.177.4051.793

- Nakashima T, Takayanagi H. Osteoimmunology: crosstalk between the immune and bone systems. J Clin Immunol. 2009;29(5):555-567. doi:10.1007/s10875-009-9316-6

- Srivastava RK, Dar HY, Mishra PK. Immunoporosis: Immunology of Osteoporosis-Role of T Cells. Front Immunol. 2018;9:657. Published 2018 Apr 5. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00657

- Khalid AB, Krum SA. Estrogen receptors alpha and beta in bone. Bone. 2016;87:130-135. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2016.03.016

- Xia B, Li Y, Zhou J, Tian B, Feng L. Identification of potential pathogenic genes associated with osteoporosis. Bone Joint Res. 2017;6(12):640-648. doi:10.1302/2046-3758.612.BJR-2017-0102.R1

- Aspray TJ, Hill TR. Osteoporosis and the Ageing Skeleton. Subcell Biochem. 2019;91:453-476. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-3681-2_16

- Clark GR, Duncan EL. The genetics of osteoporosis. Br Med Bull. 2015;113(1):73-81. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldu042

- Rocha-Braz MG, Ferraz-de-Souza B. Genetics of osteoporosis: searching for candidate genes for bone fragility. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2016;60(4):391-401. doi:10.1590/2359-3997000000178

- Zhu X, Bai W, Zheng H. Twelve years of GWAS discoveries for osteoporosis and related traits: advances, challenges and applications. Bone Res. 2021;9(1):23. Published 2021 Apr 29. doi:10.1038/s41413-021-00143-3

- Richards JB, Kavvoura FK, Rivadeneira F, et al. Collaborative meta-analysis: associations of 150 candidate genes with osteoporosis and osteoporotic fracture. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(8):528-537. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-151-8-200910200-00006

- Morris JA, Kemp JP, Youlten SE, et al. An atlas of genetic influences on osteoporosis in humans and mice [published correction appears in Nat Genet. 2019 May;51(5):920. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0415-x.]. Nat Genet. 2019;51(2):258-266. doi:10.1038/s41588-018-0302-x

- Riancho JA, Sañudo C, Valero C, et al. Association of the aromatase gene alleles with BMD: epidemiological and functional evidence. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24(10):1709-1718. doi:10.1359/jbmr.090404