Gilteritinib for Isolated FLT3+ AML Breast Relapse

Breast Isolated FLT3 Positive AML Relapse Treated with Gilteritinib in Monotherapy: Long- Term Follow-Up and Review of the Literature

Giulia Arrigo1, Stefano D’Ardìa1, Marco Cerrano1, Roberto Freilone1, Valentina Giai1, Irene Urbino1, Ernesta Audisio1, Chiara Frairia1

- Department of Oncology, Division of Hematology, AOU Città della Salute e della Scienza, Turin, Italy

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 May 2025

CITATION: Arrigo, G., D’Ardìa, S., et al., 2025. Breast Isolated FLT3 Positive AML Relapse Treated with Gilteritinib in Monotherapy: Long- Term Follow-Up and Review of the Literature. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(5). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i5.6559

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i5.6559

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

Extramedullary relapse of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a relatively common occurrence, with the FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) mutation being a significant risk factor. While gilteritinib is approved for treating relapsed/refractory FLT3+ AML, its effectiveness in extramedullary relapse is still not well established. We report the case of a 69-year-old woman diagnosed with therapy-related nucleophosmin-1 (NPM1) and FLT3-internal tandem duplication (FLT3-ITD) positive AML. She was initially treated with induction and consolidation therapy using CPX-351 (liposomal daunorubicin plus cytarabine) and subsequently received off-label azacitidine maintenance. Although she achieved complete remission with persistent measurable residual disease, 19 months later she experienced an isolated breast relapse of FLT3-ITD+ AML. The patient was treated with single agent gilteritinib, which led to a rapid and sustained complete regression of the breast nodule, maintained after 44 courses of treatment. This case demonstrates that target therapy with gilteritinib can be an effective option for isolated extramedullary relapse of FLT3-ITD+ AML.

Keywords

FLT3, AML, gilteritinib, extramedullary relapse, breast cancer

Introduction

Therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia (t-AML) is a disease that arises as a delayed complication following cytotoxic treatment for a primary cancer or a non-neoplastic disorder. Until 2022, it was considered a category of AML, but with the updated 2022 European leukemiaNet (ELN) guidelines, it became a diagnostic qualifier for the AML-defining category. This type of leukemia accounts for approximately 7% of all newly diagnosed AML cases and it seems to be the direct consequence of mutational events induced by cytotoxic therapy (chemotherapy, including mostly treatment with topoisomerase II inhibitors, radiotherapy) and/or selection of chemotherapy-resistant clones. The diagnostic and prognostic workup for AML includes testing for several mutations, with about 30% of newly diagnosed AML cases carrying a mutation in the FLT3 gene, which encodes a membrane-bound tyrosine kinase protein. The most common FLT3 mutations are FLT3-ITD and tyrosine kinase domain (TKD) mutations, present in roughly 20-30% and 7% of AML patients, respectively. These FLT3 mutations, especially FLT3-ITD, are considered poor prognostic factors in terms of relapse-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS), irrespective of the FLT3-ITD allelic ratio. Thus, patients with FLT3-ITD+ AML are generally recommended to undergo allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) after achieving complete remission (CR). Several studies have highlighted the frequent occurrence of FLT3 mutations in patients with extramedullary involvement (EMI), which refers to the presence of leukemic cells outside of the blood or bone marrow, typically in organs such as the skin, bone, and lymph nodes. EMI can develop simultaneously with, before, or after the initial AML diagnosis, and it may occur at diagnosis or relapse. However, treatment guidelines for EMI remain lacking due to the rarity of this phenomenon, which affects only 3–8% of adult AML patients. Some recent reports suggest that targeted therapies, including FLT3 inhibitors, may be effective for treating EMI. Gilteritinib, a second-generation selective FLT3 inhibitor, is active against both FLT3-ITD and FLT3-TKD mutations. Gilteritinib has been approved as a monotherapy for FLT3+ AML in first or subsequent relapses, regardless of the FLT3 status at diagnosis. Generally, patients treated with gilteritinib obtain a CR in more than 30% of cases with an OS of about 10 months and a low toxicity profile. Notably, up to 30% of AML patients who are FLT3-negative at diagnosis may acquire a FLT3 mutation at relapse, highlighting the importance of re-testing for FLT3 mutations at the time of relapse. In this report, we present the case of a FLT3-ITD mutated AML patient with isolated breast EMI at relapse, who was successfully treated with gilteritinib.

Case report

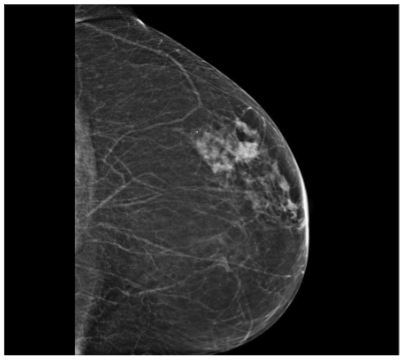

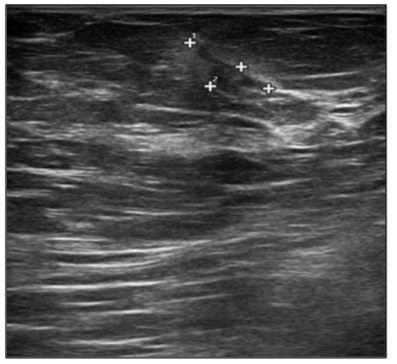

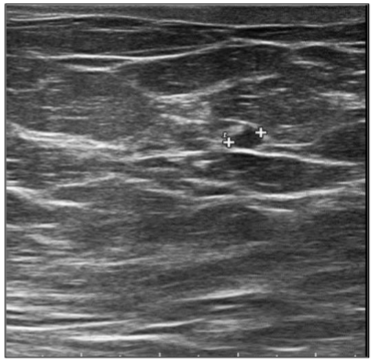

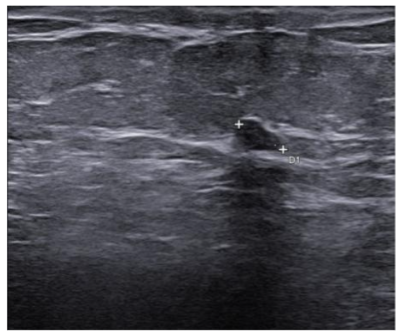

In September 2019, a 69-year-old woman presented to the emergency department of the University Hospital Città della Salute e della Scienza – Turin (Italy), reporting extreme fatigue and dyspnea. She had no comorbidities except for a medical history of papillary thyroid cancer, treated with thyroidectomy and radiotherapy 13 years before. Her complete blood count revealed anemia, thrombocytopenia and leukocytosis (Hb: 7.8 g/dL, PLT: 37 × 109/L, WBC: 45 × 109/L), while her physical examination was normal. The bone marrow smear showed 84% of blasts with myeloid immunophenotype (CD45, CD13, CD33, HLA-DR, lysozyme, CD36, CD64, CD11bc, partial CD14, and CD4 positive), molecular biology showed NPM1 mutation and FLT3-ITD positivity, while karyotype was normal (46, XX, 20/20). Consequently, a diagnosis of FLT3-ITD+ and NPM1 mutated t-AML was made. Induction chemotherapy was started with CPX-351 (liposomal daunorubicin 44 mg/m2 and cytarabine 100 mg/m2), obtaining CR with a 3-log NPM1 reduction (0.177). She was consolidated with CPX-351 (liposomal daunorubicin 29 mg/m2 and cytarabine 65 mg/m2 day 1 and 3), remaining in CR with persistent low level of measurable residual disease (MRD), NPM1 0.34. Meanwhile, we found a suitable HLA matched donor, but the patient refused the transplant procedure. Thus, we decided to start off-label azacitidine as maintenance therapy (50 mg/m2 subcutaneous daily for 5 days, every 28 days). Maintenance therapy was globally well tolerated, and the patient experienced only positivity for COVID-19 without need of hospitalization or additional care. She remained in CR with persistent MRD in BM (NPM1 0.044 after 12 cycles). During the fifteen course (May 2021), we found a palpable right mammary nodule on physical examination, confirmed on ultrasound, with a diameter of 18 x 11 mm. We stopped azacitidine and we promptly biopsied the nodule with a diagnosis of breast infiltration by AML blasts carrying the NPM1 mutation. CT scan and PET of chest, neck and abdomen were negative, and BM evaluation showed 1% blasts, with NPM1 0.044. The FLT3-ITD mutation resulted positive on breast cells while negative on medullary blasts. Thus, concluding for extramedullary relapse of AML FLT3-ITD mutated, we decided to start gilteritinib as single agent, at a dose of 120 mg daily. After 30 days, mammary ultrasound showed a reduction in diameter of the nodule, and in 4 months, the lesion has completely disappeared. The PET scan performed after 5 months of treatment was persistently negative and confirmed the absence of other uptakes. BM re-evaluation showed no blasts, with NPM1 0.006. Today, after 44 months of treatment, our patient is still in CR without signs of clinical and radiologic relapse. We continue monitoring her MRD status every two months on peripheral blood, as shown in table 1. Globally, therapy has been always well tolerated. In January 2024, we had to stop gilteritinib for 28 days due to pyelonephritis and sepsis treated with broad spectrum antibiotics. During this time, she remained in complete remission without any sign of relapse. After some months, in September, our patient has undergone exeresis of basal cell carcinoma, without complications and without need of stopping gilteritinib.

Table 1: MRD status (NPM1 level in BM and PB)

| Date | Time | Source | Result [(PM1-A/ABL copies) %] |

|---|---|---|---|

| September 2019 | At diagnosis | BM | 481 |

| October 2019 | After induction | BM | 0.177 |

| December 2019 | After first consolidation | BM | 0.034 |

| August 2020 | After 6° cycle of azacitidine | BM | 0.006 |

| February 2021 | After 12° cycle of azacitidine | BM | 0.044 |

| May 2021 | At extramedullary relapse | BM | 0.006 |

| January 2022 | After 7m of gilteritinib | PB | 0.0006 |

| January 2022 | After 7m of gilteritinib | BM | Negative |

| June 2022 | After 12m of gilteritinib | BM | Negative |

| August 2022 | After 14m of gilteritinib | PB | Negative |

| September 2022 | After 15m of gilteritinib | PB | 0.0026 |

| December 2022 | After 18m of gilteritinib | PB | Negative |

| February 2023 | After 20m of gilteritinib | PB | 0.0043 |

| April 2023 | After 22m of gilteritinib | PB | Negative |

| July 2023 | After 25m of gilteritinib | PB | Negative |

| August 2023 | After 27m of gilteritinib | PB | Negative |

| September 2023 | After 28m of gilteritinib | PB | Negative |

| October 2023 | After 29m of gilteritinib | PB | Negative |

| November 2023 | After 30m of gilteritinib | PB | Negative |

| December 2023 | After 31m of gilteritinib | PB | Negative |

| February 2024 | After 33m of gilteritinib | PB | Negative |

| April 2024 | After 35m of gilteritinib | PB | Negative |

| June 2024 | After 37m of gilteritinib | PB | 0.0009 |

| August 2024 | After 39m of gilteritinib | PB | Negative |

| September 2024 | After 40m of gilteritinib | PB | Negative |

| November 2024 | After 42m of gilteritinib | PB | Negative |

| January 2025 | After 44m of gilteritinib | PB | Negative |

Discussion

Myeloid sarcoma (MS), also referred to as extramedullary myeloid infiltration, was first described in 1811 by Burns. Initially, the tumor was called “chloroma” because of its greenish hue, which was later linked to the presence of the MPO (myeloperoxidase) enzyme by King in 1853. The tumor was identified as a mass composed of myeloid blasts, causing disruption in the normal tissue structure. The connection between MS and myeloid leukemia was first established in 1893 by Dock. Histologically, MS consists of immature granulocyte precursors, such as myeloblasts, promyelocytes, myelocytes, and granulocytes. Core biopsy is preferred over fine needle aspiration for the histologic and immunophenotypic evaluation, FISH, PCR and NGS allows a better understanding of the patient’s prognosis and identification of potential treatment targets. It is observed in 3-8% of adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia. It can occur in the context of intramedullary AML (synchronous extramedullary AML), or in an isolated form with an essentially normal bone marrow (isolated extramedullary AML; also called “nonleukemic” or “aleukemic”), which is usually followed by the development of metachronous intramedullary AML. Its frequency is higher in the post-allo-HSCT relapse setting with about 15% of all post allo-HSCT AML relapses being isolated EMI. While the exact cause of MS development remains unclear, it is thought to involve the migration of leukemia blasts to extramedullary sites, facilitated by specific adhesion molecules found on the blast cell surfaces. Age might influence the presence of MS; most studies have reported a median age at diagnosis ranging from 46 to 59 years, with approximately 52–59% of affected patients being male. Certain genetic features, including trisomy 8, monocytoid differentiation of blasts, MLL rearrangements, as well as CD56 positivity and the absence of CD117 (c-kit), are associated with an increased risk of developing MS in AML. These factors enhance the ability of leukemic cells to migrate to areas beyond the bone marrow. Recent reports have highlighted the frequent occurrence of FLT3 mutations in patients with EMI. FLT3-ITD mutations were the first molecular abnormalities to be identified in MS cells with initial studies detecting the mutation in up to about 30%, which is similar to the frequency noted for typical AML. NPM1 mutations are detected in up to 50% of cases, again comparable to conventional AML. MS in the breast is extremely rare, making up only about 3% of all MS cases, according to a Mayo Clinic study. Due to its infrequency, it is often mistaken for other breast malignancies, such as lobular carcinoma, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, or small round blue cell tumors. A recent review by Sharma et al. examined 67 previously reported cases, 66 of which were women and only one was a man. In most instances, breast MS presents as a rapidly enlarging mass, which may affect one or both breasts. Nipple retraction is generally not observed. Right-sided breast involvement is more common than left-sided. In terms of imaging, MS in the breast typically appears as a large, irregular, non-calcified mass with poorly defined, “feathery” margins, a characteristic finding consistent with the mammograms of the patients in the study. FDG-PET/CT at diagnosis, after treatment completion and at the time of suspected relapse is an important tool that allows for timely adjustments to the management strategy.

Conclusion

Gilteritinib seems to be effective in the treatment of EMI with a good toxicity profile. We present the first reported case of a successful single agent treatment of isolated extramedullary breast relapse in FLT3-ITD+ AML, with a persistent remission at the extended follow-up. CR has been sustained from 44 months, without any consolidation treatment with allo-HSCT. Further research is required to confirm the efficacy of gilteritinib in treating extramedullary relapse. Include and enroll patients with EMI onto AML clinical trials is necessary to find new treatment options and prospectively to evaluate their outcomes in comparison to patients without extramedullary AML.

References

- Döhner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood. 2017;129(4):424-447. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-08-733196

- Döhner H, Wei AH, Appelbaum FR, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2022 recommendations from an international expert panel on behalf of the ELN. Blood. 2022;140(12):1345-1377. doi:10.1182/blood.2022016867

- Pollyea DA, Bixby D, Perl A, et al. Acute Myeloid Leukemia, Version 2.2021 Featured Updates to the NCCN Guidelines. JNCCN Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2021;19(1):16-27. doi:10.6004/JNCCN.2021.0002

- Welch JS, Ley TJ, Link DC, et al. NIH Public Access. 2013;150(2):264-278. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.023.

- Papaemmanuil E, Ph D, Gerstung M, et al. Europe PMC Funders Group Genomic Classification and Prognosis in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. 2016;374(23):2209-2221. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1516192.Genomic

- Perl AE, Martinelli G, Cortes JE, et al. Gilteritinib or Chemotherapy for Relapsed or Refractory FLT3 -Mutated AML. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;381(18):1728-1740. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1902688

- Patel JP, Gönen M, Figueroa ME, et al. Prognostic Relevance of Integrated Genetic Profiling in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366(12):1079-1089. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1112304

- Kiyoi H, Naoe T, Nakano Y, et al. Prognostic Implication of FLT3 and N-RAS Gene Mutations in Acute Myeloid Leukemia.

- Fergun Yilmaz A, Saydam G, Sahin F, Baran Y. Granulocytic Sarcoma: A Systematic Review. Vol 3.; 2013. www.AJBlood.us/

- Solh M, Solomon S, Morris L, Holland K, Bashey A. Blood Reviews Extramedullary acute myelogenous leukemia. YBLRE. 2016;30(5):333-339. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2016.04.001

- Bourlon C, Lipton JH, Deotare U, et al. Extramedullary disease at diagnosis of AML does not influence outcome of patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant in CR1. Eur J Haematol. 2017;99(3):234-239. doi:10.1111/ejh.12909

- Bakst RL, Tallman MS, Douer D, Yahalom J. How I treat extramedullary acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2011;118(14):3785-3793. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-04-347229

- Kida M, Kuroda Y, Kido M, Chishaki R, Kuraoka K, Ito T. Successful treatment with gilteritinib for isolated extramedullary relapse of acute myeloid leukemia with FLT3-ITD mutation after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Int J Hematol. 2020;112(2):243-248. doi:10.1007/s12185-020-02855-4

- Kumode T, Rai S, Tanaka H, et al. Targeted therapy for medullary and extramedullary relapse of FLT3-ITD acute myeloid leukemia following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Leuk Res Rep. 2020;14(August):100219. doi:10.1016/j.lrr.2020.100219

- Perrone S, Ortu La Barbera E, Viola F, et al. A Relapsing Meningeal Acute Myeloid Leukaemia FLT3-ITD+ Responding to Gilteritinib. Chemotherapy. 2021;66(4):134-138. doi:10.1159/000518356

- Kim RS, Yaghy A, Wilde LR, Shields CL. An Iridociliochoroidal Myeloid Sarcoma Associated with Relapsed Acute Myeloid Leukemia with FLT3-ITD Mutation, Treated with Gilteritinib, an FLT3 Inhibitor. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020;138(4):418-419. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.0110

- Ji Y, Wan Z, Yang J, Hao M, Liu L, Qin W. The safety and efficacy of the re-administration of gilteritinib in a patient with FLT3-mutated R/R AML with CNS relapse: a case report. Front Oncol. 2024;14. doi:10.3389/fonc.2024.1402970

- Nicolas Vignal LKELACHJS et al. Favorable pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of gilteritinib in cerebrospinal fluid: a potential effective treatment in relapsing meningeal acute myeloid leukemia FLT3-ITD patients. Haematologica | 108 September 2023.

- McMahon CM, Canaani J, Rea B, et al. Gilteritinib induces differentiation in relapsed and refractory FLT3-mutated acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv. 2019;3(10):1581-1585. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2018029496

- Krönke J, Bullinger L, Teleanu V, et al. Clonal evolution in relapsed NPM1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2013;122(1):100-108. doi:10.1182/blood-2013-01-479188

- Wei AH, Döhner H, Pocock C, et al. Oral Azacitidine Maintenance Therapy for Acute Myeloid Leukemia in First Remission. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;383(26):2526-2537. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2004444

- Burns A. Observations of surgical anatomy, head and neck. Edinburgh: Thomas Royce; 1811 p 364–6.

- King A. A case of chloroma. Monthly J Med 1853;17:97.

- Dock G. Chloroma and its relation to leukemia. Am J Med Sci 1893;106(2):153–7.

- Yan C, Zhou JL, Wu JH, Zhang JZ. Case Report Synchronous Granulocytic Sarcoma of the Breast and Spine: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Vol 121.; 2008.

- Gomaa W GAEEBKGA. Primary myeloid sarcoma of the breast: a case report and review of literature. J Microsc Ultrastruct 2018;6(4):212–4.

- Shallis RM, Gale RP, Lazarus HM, et al. Myeloid sarcoma, chloroma, or extramedullary acute myeloid leukemia tumor: A tale of misnomers, controversy and the unresolved. Blood Rev. 2021;47. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2020.100773

- Yui J MMPMGNAKAEM et al. Myeloid sarcoma: the Mayo Clinic experience of ninety-six case series. Blood 2016 Dec 2;128(22):2798.

- Sharma A, Das AKr, Pal S, Bhattacharyya S. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of granulocytic sarcoma presenting as a breast lump – Report of a rare case with a comprehensive literature search. J Lab Physicians. 2018;10(01):113-115. doi:10.4103/jlp.jlp_114_17

- Jelić-Puškarić B OKSPAOKDKSIJB. Myeloid sarcoma involving the breast. Coll Antropol 2010;34(2):641-4.

- Zhang XH ZRLY. Granulocytic sarcoma of abdomen in acute myeloid leukemia patient with inv(16) and t(6;17) abnormal chromosome: case report and review of literature. Leuk Res 2010;34(7):958–61.

- Ganzel C, Lee JW, Fernandez HF, et al. CNS involvement in AML at diagnosis is rare and does not affect response or survival: data from 11 ECOG-ACRIN trials. Blood Adv. 2021;5(22):4560-4568. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2021004999

- Heuser M, Ofran Y, Boissel N, et al. Acute myeloid leukaemia in adult patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology. 2020;31(6):697-712. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2020.02.018

- Cunningham I, Kohno B. 18FDG-PET/CT: 21st century approach to leukemic tumors in 124 cases. Am J Hematol. 2016;91(4):379-384. doi:10.1002/ajh.24287

- Grunwald MR, Levis MJ. FLT3 tyrosine kinase inhibition as a paradigm for targeted drug development in acute myeloid leukemia. Semin Hematol. 2015;52(3):193-199. doi:10.1053/j.seminhematol.2015.03.004

- Urbino I, Secreto C, Olivi M, et al. Evolving therapeutic approaches for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia in 2021. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(20). doi:10.3390/cancers13205075

- Francesco Angotzi EBCSMBGGM et al. 1523 Disease Course and Treatment Patterns of Acute Myeloid Leukemia with FLT3 Mutations and Myeloid Sarcoma Reveal High Efficacy of Gilteritinib: A Multicentric Retrospective Study. ASH oral and poster abstract.