Home Monitoring Calibration Issues in Pre-Diabetes Testing

Further Problems in Tester Calibration and Control Solution in Home Monitoring of Pre-Diabetes

Franco Pavese1,

- Independent Scientist (former Research Director in Metrology at CNR, Italy)

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 May 2025

CITATION: Pavese, F., 2025. Further Problems in Tester Calibration and Control Solution in Home Monitoring of Pre-Diabetes. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(5). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i5.6516

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i5.6516

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

In previous publications, the author has reported some specific problems in checking glycaemia level in marginal diabetes, mainly due to the accuracy of the checks in that very narrow range of values, an issue particular important because above the upper limit, 125 mg/dL, the diabetes disease is considered to have already begun, while below that max value a diet is considered sufficient.

Since the off-shelf calibration of the testers used for home glucose level checks has been found not stable over time, the systematic use of control solutions provided by tester manufacturers is mandatory. However, the procedure for identifying potential calibration problems, even after a home calibration of both the batch and tester, is largely inaccessible to most patients, as demonstrated in the paper. Thus, improvements in the precision of the strip testers is urgently needed for that range, and, if stability of the standard solution cannot be ensured over a sufficient long term, the deadline for recalibration must be specified and the certificate of the control solution should be provided according to ISO Standards—and also reported on the tester/strip instruction sheets. Finally, relevant Standards should be more specific about this critical range.

Keywords

- Tester Calibration

- Control Solution

- Home Monitoring

- Pre-Diabetes

- Glycaemia

1. Introduction

In previous publications, 1–3 the author has highlighted specific problems in accurately checking glycaemia level in marginal diabetes, particularly due to the limited accuracy of measurements within the very narrow range of values: 100–125 mg/dL (±12 % only wide). The issue is particular important for its upper limit, above which the diabetes disease is considered to have formally begun, while below that maximum value, dietary management, potentially supplemented with Glucophage®, is often deemed sufficient.

The original calibration of the testers used for checking glucose level is not ensured to be provided and most calibrations were found not stable in time (generally drifting to higher indications), 1 thus requiring a systematic use of (calibrated) control solutions provided by the tester manufacturers—already often a too much specific requirement for most patients’ capabilities.

Furthermore, patients often struggle to identify the correct control solution for the marginal range as manufacturers may not specifically cater to this range or may use varying terminology, such as “range 3” to describe it. In addition, as already pointed out in Ref. 1, a control solution is what in metrology/testing is called a “reference material”, subjected to very specific requirements and controls for their production and use—e.g., ISO 15197-2015, 4 ISO 17034 and 33403.

This paper aims to report additional inconsistencies that have recently been found in using the instrumentation calibration procedure reported in Refs. 1–3, highlighting the possible need for double checks when switching test strip batch and/or control solution lots, particularly when their validity time is close to expiration date—when supplied.

2. Methodology of the test and Recall of the instruments calibration procedure

The methodology for conducting the home tests is the one already reported in Refs. 1—2.

A generic patient is supplied with the following means and information for the used instrumentation:

- Batch of test strips (in addition to lot name and deadline of use)

- a) The range of valid measured strip values, say: 128—158 mg/dL (7.1—8.8 mmol/L);

- b) Middle-range value, called “aimed value”, in that case: 143 mg/dL (8.0 mmol/L).

- Control solution sample

- c) Lot name (See Note 1 below) and use deadline;

- d) “Range 3” or equivalent denomination—sometimes confusing—for the valid glucose concentration range.

- Specific tester of the same manufacturer

- e) Instructions for use of the instruments.

Note 1: Considering the high cost of a control solution batch (4 mL), one cannot assume that it can only be used for the current test strip batch, but be valid for any strip batch used within the deadline time indicated for the solution.

Note 2: The currently used tester should measure the glycaemia value of each drop of the control solution by means of the current batch of test strips used for blood glycaemia level.

In summary, the procedure suggested in Ref. 2 is the following, by using the current tester and strip batch:

- First, the test strip batch is calibrated. Assuming, for example, that the nominal value for the range is 140 mg/dL and the mean value indicated by the tester is, e.g., 146 mg/dL, the correction value of the strip indications of that batch will be 146/140 = 1.043;

- Then the tester calibration comes, using another strip of the same batch and a second drop from the control solution bottle—the first drop is discarded as can be contaminated by the leftover of the previous bottle use, to better ensure that the second has the same composition as the bulk in the bottle;

- If the tester reading is, for example, 125 mg/dL, then the correction value for the tester indication will be 125/140 = 0.893;

- Thus the total correction of any strip test value will be, in that case: 1.043×0.893 = 0.931 (–6.9%), valid only until the next calibration, mandatory for each subsequent strip batch. (However, the tester calibration may be considered possibly obsolete if its last calibration is too old).

3. Evidence of new tests becoming necessary in specific cases

The possibility of occurrence of the latter case above (in above (4)-parentheses) was recently observed as follows: (i) at the end of a strip batch, no final tester calibration was performed because all results of the glucose tests performed with it were considered reasonably consistent with each other; (ii) at the start of use of the next strip batch, a step up-change in the glucose level indication occurred. In order to check for its validity, not justified by the calibration of the strip batch, a new tester calibration was performed using the same control solution: a significant step-change of calibration was also obtained. That occurrence made necessary exceptional double checks to resolve the reliability of the observed occasional increase of the glucose level.

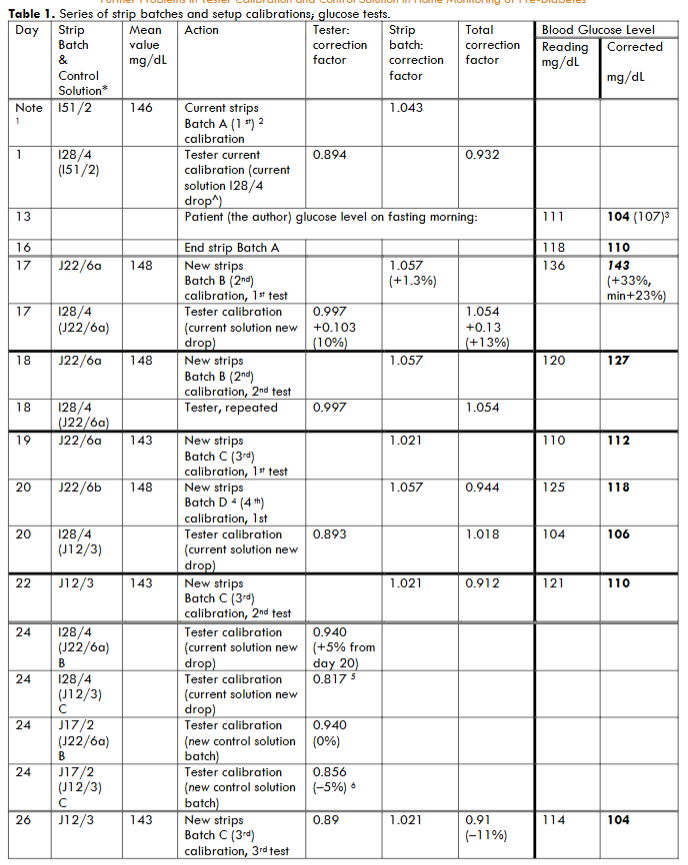

In Table 1, such check sequence is described in details together with the relevant previously recorded ones, and will be analysed in Section 4 and discussed in Section 5.

The difference in subsequent total (i.e. strip and tester) calibration correction between the strip batch A and the subsequent, B, in days 1 and 17 in Table 1 was found very large, 13%, more than acceptable: at the middle of the pre-diabetes range (only 25 mg/dL wide) this corresponds to 16 mg/dL, so that the corrected value (143 mg/dL)) comes above 125 mg/dL, the range limit, so bringing into the diabetes range—as confirmed by a second test.

The large variation between days 1 and 17 also in the tester calibration needed a double verification. On the subsequent day, day 18, a second test for patient blood resulted in a much lower indication and a third test on day 19 also a lower one.

4. Analysis of the above tests

The anomaly observed in Table 1, “Glucose Level” columns, arises from the comparison of the blood test results of days 16 and 17.

On day 16, the end of batch A showed a glucose calibrated level of 110 mg/mL, while the first test of batch B on day 17 reported a calibrated level of 143 mg/dL, both taken on fasting morning as usual, and without any justification arising from peculiarities in the behaviour/competence/diet of the patient doing the tests. A +23% calibration difference is found, far above the normal repeatability of the procedure. The previous test with batch A was only a few mg/dL different, according to previous calibration done 35 days earlier and on day 17—being the difference of A and B batch calibrations only 1.3% different, while difference in “Total calibration factor” in Table 1 from day 1 and 17 was of +13%.

Thus, the tester calibration change does not justify the different values of blood tests. Then, an apparent inconsistency came up: a further test was made on day 18, with strip batch B, the total calibration provided a different/lower value, 127 mg/dL, 9% different from day 16 with tester calibration unchanged when still using the current control solution.

Consequently, other cross checks were necessary on days 19-22, also using strip batches C and D and the same control solution batch. The strip checks, using again batches B and C and with the tester check still changing calibration value, provided glucose levels basically within a range of corrected value 106-118 mg/dL.

The probability can thus be considered high for the whole strip batch B, J22/6, being defective—this is a quite different fact from finding a test providing a false indication, and new with respect to the facts discussed in Refs. 1–3.

Finally, to allow subsequent use of batch (J12/3), a re-calibration was performed on day 24 of the current tester calibration (I28/4) with the brand new batch (J17/2), by using both strip batches B and C: the calibration resulted to be identical for the two strip batches using the old control solution, while two values differing by 5% was obtained using the new control solution. The mean correction value of the 4 tests, 0.888, differs from the previous calibration of the first control solution, 0.997 by 9%, while the mean difference between the two control solutions was 11%, thus larger than the dispersion of the tests made in subsequent times with the same batch of strips that are of the order of 5%—note that the checks on control solution on the same tester depends also on the calibration of the strips batch used, which may be different over time.

5. Discussion

Some of the above results exceeded with reasonable confidence the dispersion limit ~5% for the strips, and ~10% total. These findings confirmed that strip batch B only provided unreliable indications, with a higher probability of false readings exceeding the pre-diabetes range—i.e. higher than 125 mg/dL, so potentially miss-indicating that the patient health had drifted to diabetes disease.

A statistics of such an occurrence, the first observed by the author, is not at present available, but even this single occurrence is alarming, so worth to be reported, because its detection with high confidence is certainly out from the reach of the vast majority of the patients making their checks.

Even for an expert person it is not so easy to evaluate such situation, so it is reasonable to advise always performing a new tester calibration just near the end of the current strip batch (even if the tester correction could be found unchanged) and before starting a new strip batch.

The reported case, obtained with materials from a reputed manufacturer, confirms author’s standing position: the need to insist increasing the accuracy of the test materials made available by the manufacturers, in two directions:

- Decreasing the case-to-case variability of the indications for each single batch (of minimum 25 strips), i.e. increasing the precision of the strips. This should not be confused with the indication already existing on the strip box, e.g., Level 3 128-158 mg/dL (143 mg/dL): the level in parentheses is the mean value taken as the “nominal” value for that batch (and the one to be used). The ±12.5% range only provides the range of expected valid strip batch readings of the patient’s blood; it is not the valid dispersion of the indications for the same blood drop due to batch actual quality/reproducibility that one should expect. Should that be the intention of the manufacturer, it would not be correct.

- The above test does not indicate yet the accuracy of the measurement, i.e. the true interest of the patient/doctor, because the tester itself may introduce false readings, even exceeding the 5% reproducibility necessary for that very narrow range. The subject matter of this paper demonstrates just the fact that the manufacturers do not provide a warranty about the testers being sold calibrated off-shelf, or remaining calibrated over time. Direct experience has too often shown that not ensuring calibration is a common case, confirmed and demonstrated above and in Refs. 1–3. The only remedy provided by the manufacturer is the “control solution”, in metrological term a “reference material”, whose characteristics and use (the “specs”) are regulated by ISO standards, also valid for them. As already discussed in Refs. 1–3 this is not the real situation: nothing is certified about the provided solutions, often not even about the nominal value and expected precision, only validity (i.e. stability?) in time, typically for 1 year.

6. Conclusions

As demonstrated in this paper, a reliable procedure for identifying potential issues with strip batch, even after a home calibration of both batch and tester, is largely inaccessible to most patients in case of evidence of dubious test results.

The issue is aggravated by the fact that patients, in such preliminary phase of their possible evolution to the full disease, tend to scarcely feel committed in making frequent checks (e.g. 3/week and for half yearly weeks should be a minimum), also due to the cost and to the need for frequent fasting morning tests; on the other hand, the author got information about a current medical procedure where two tests under passing the 125 mg/dL limit for a few days are sufficient to consider the patient having got the full disease, and possibly already needing insulin—and consequent daily mandatory checks.

In conclusion, improvements in the precision of the test strips is still urgently needed, and, if stability of the standard solution cannot be ensured over a sufficient long term, the term of recalibration must be specified and a certified control solution should be mandatory and provided according to the specific ISO standards—and alerting instructions also be reported on the tester/strip guidance sheets.

Furthermore, also ISO standards, in their present elaboration, are missing due attention to the specific pre-diabetes range 100–125 mg/dL: at present the guidelines (e.g. 4) concern only two continuous field, <100 mg/dL and 100–150 mg/dL, so missing the pre-diabetes boundary 125 mg/dL, a regulation formally inconsistent and critical for diabetes classification related to the patients tests.

In the mean time, the pre-diabetes patients must correct the tester indications at least according to the calibration of each new-used strip batch, by using the correct (middle) range value reported on the strip box, a very simple operation (or the tester manufacturer should include it—unknown to him—as mandatory among the (patient’s manual) tester functions).

References

- Pavese F. A testing/metrological look at the accuracy of glucose strip measurements in home care for marginal diabetes, for mitigating diabetic kidney disease. J. of Nephrology 2022;35023077: 5. Doi: 10.1007/s40620-021-01224-6.

- Pavese F. Findings from a Metrological Analysis of Test-Strip Use in Diabetes Home-Care Control: A Confirmation. Clinical Cases in Medicine, Medtext Publications 2022; 2(Article 1016): 1–3. ISSN: 2770-2359.

- Pavese F. A long-term case study on marginal diabetes: demonstrating the need for effective calibration of home test devices. Medical Research Archives [S.l.]; 2024;12(9): ISSN 2375-1924. Available at: https://esmed.org/MRA/mra/article/view/5873.

- BS EN ISO 15197:2015. Document consulted: ® Tracked Changes, compares BS EN ISO 15197:2015 and BS EN ISO 15197:2013: In vitro diagnostic test systems — Requirements for bloodglucose monitoring systems for self-testing in managing diabetes mellitus. © The British Standards Institution 2019. Published by BSI Standards Limited 2019.