Infective Endocarditis in Pediatric Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

Infective Endocarditis Complicated by Rupture of Cerebral Mycotic Aneurysm in a Child with Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Case Report with Review of the Literature

Wided Gamaoun, Amel Maghrebi, Elyes Neffati

1 Department of Radiology, Sahloul University Hospital, Sousse, Tunisia

2 Department of Cardiology, Sahloul University Hospital, Sousse, Tunisia

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED 31 August 2025

CITATION Gamaoun, W., Maghrebi, A., et al., 2025. Infective Endocarditis Complicated by Rupture of Cerebral Mycotic Aneurysm in a Child with Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Case Report with Review of the Literature. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(8). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i8.6691

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i8.6691

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Background: Infective endocarditis (IE) is a rare entity in paediatrics with congenital heart disease representing the most common risk factor. Only few cases of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) related IE in paediatrics were reported in the literature and the risk of IE complicating HCM is still not well defined especially in paediatric population. HCM is a primary genetic myocardial disease characterized by asymmetric ventricular septal hypertrophy that cannot be explained by abnormal loading conditions. Although, it is a common genetic disorder in adults, it is rare in the paediatric population and is an uncommon substrate for infective endocarditis. Our objective is to report an unusual case of infective mitral endocarditis complicated by rupture of cerebral mycotic aneurysm in a 10-year-old child with previously unknown obstructive HCM illustrating the emerging role of obstructive HCM as a risk condition in paediatric IE with intercurrent neurologic complications aggravating the patient’s clinical status despite successful medical and surgical treatments.

Keywords: Obstructive, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, mitral endocarditis, cerebral mycotic aneurysm, complicated, paediatrics

INTRODUCTION

IE remains a rare but a serious condition in paediatrics. The incidence of paediatric IE has been estimated to be 0.43-0.69 cases per 100,000 children per year. Cyanotic and complex congenital heart disease, left sided defects or endocardial cushion defect represent the most frequent risk conditions. In minority of cases, IE can occur without known structural heart disease or chronic predisposing condition. These cases exhibit worse prognosis likely due to more aggressive pathogen. Among these cases, the identification of HCM in the setting of complicated endocarditis is rare and unusual occurrence especially in paediatric population.

HCM is the most common inherited heart disease. It is an autosomal dominant disorder with variable penetrance and is generally caused by a pathogenic mutation in the genes encoding sarcomeric proteins, but there are also non genetic forms, with its prevalence in the general population 1:500, however it is rare in children and has an incidence of 0.47/100,000 children.

It is characterized by asymmetric ventricular septal hypertrophy, muscular hypercontractility and fibrosis with absence of other conditions that could possibly contribute to left ventricular hypertrophy such as severe hypertension or aortic stenosis. In adults, it is characterized by a left ventricular wall thickness of 15 mm or more and in children, it is defined as a wall thickness that is at least 2 standard deviations above the mean for age, sex or body size or left ventricular wall thickness of 13 mm or more.

HCM could be clinically asymptomatic with many patients remain free of clinically significant symptoms, or associated with life threatening complications such as cardiac arrhythmias consequent of a disorganized myocardial architecture, interstitial collagen deposition and replacement scarring after myocyte death as a result of coronary microvascular mediated flow dysfunction and ischemia. Furthermore, mycotic aneurysms represent rare complications in patients with IE and occur as a result of septic embolization and weakening of the arterial wall. Aneurysm rupture is observed approximately in 1.7 % of infective endocarditis and are associated with high morbidity and mortality.

Our aim is to report a rare new case of complicated IE with rupture of intra cranial mycotic aneurysm in a paediatric patient with sub clinic obstructive HCM. The observation supported the increased risk of IE in HCM with left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO) and left atrial dilatation and illustrated a rare paediatric case of left heart IE neurologic complication.

CASE PRESENTATION

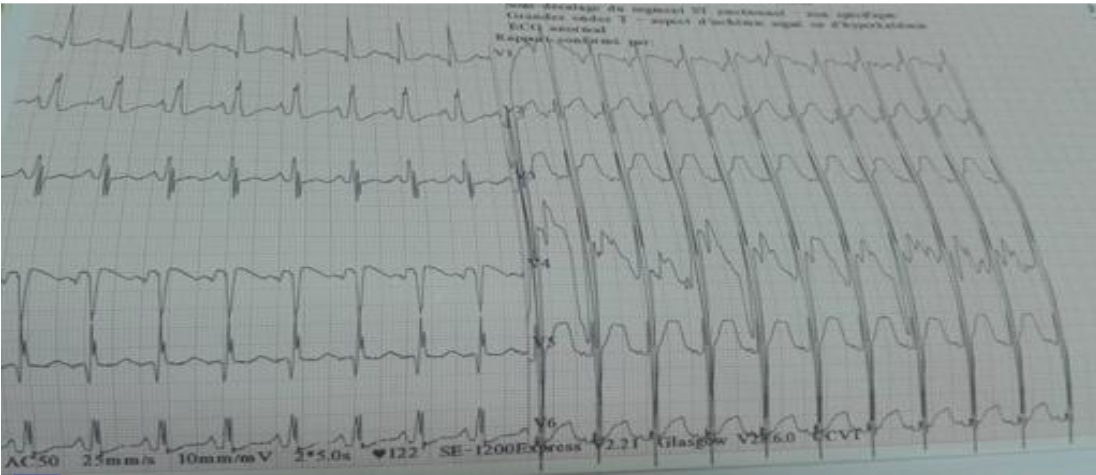

A previously healthy 10-year-old child was admitted to our hospital for prolonged fever and dyspnea. On physical examination, he was febrile with a temperature of 38.5°C, and tachycardic. A systolic murmur was detected at the mitral focus. The electrocardiogram showed a sinusal tachycardia at 150 bpm and a left ventricular hypertrophy as shown in Figure 1.

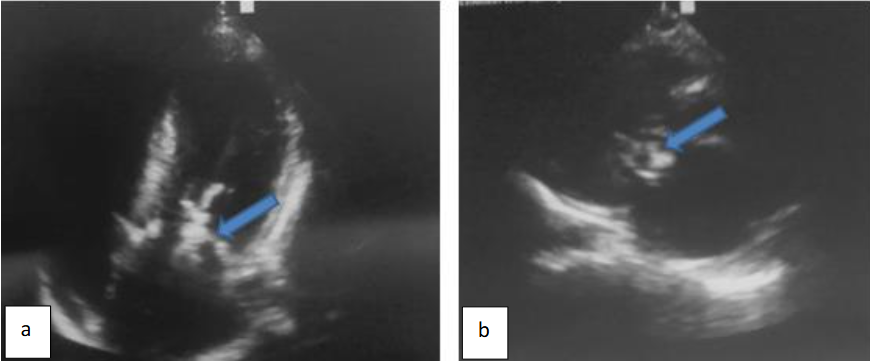

Initial laboratory tests revealed elevated C-reactive protein 80 mg/l. Three sets of blood cultures were performed, however remain negative. The chest X-ray showed cardiomegaly. The transthoracic echography demonstrated left ventricle low compliance with asymmetric wall hypertrophy located at the level of the basal and medial interventricular septum measuring 22 mm, as depicted in Figure 2.

Furthermore, a voluminous mobile vegetation measuring 40 mm in long axis was seen mutilating the mitral valve anterior leaflet and prolapsing into the left auricle which was dilated, as shown in Figure 3.

Pulsed doppler detected marked mitral valve regurgitation as depicted in Figure 4.

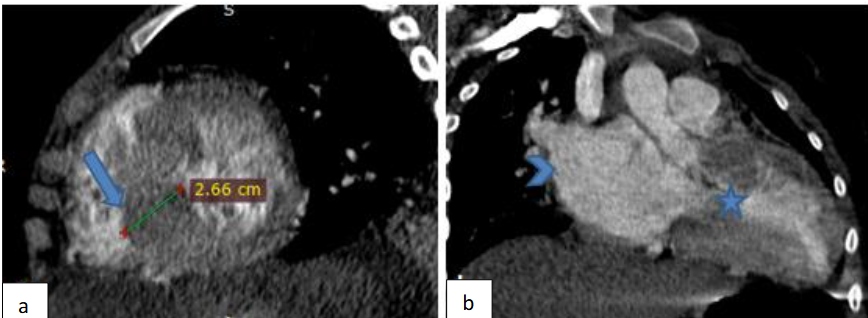

A cardiac Angio CT was performed and confirmed the left ventricular asymmetric septal hypertrophy narrowing the left ventricular chamber as shown in Figure 5.

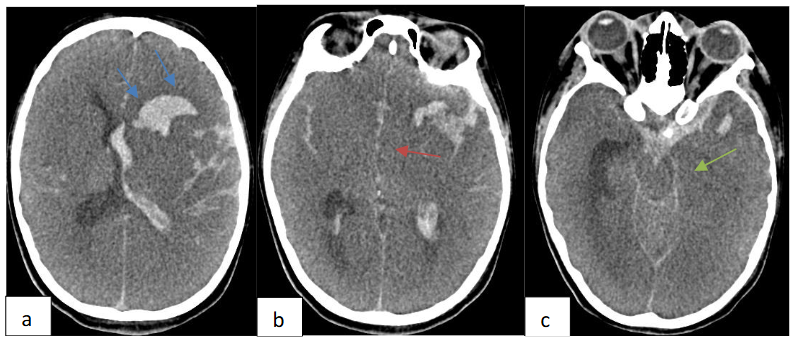

The diagnosis of IE complicating HCM was retained on the basis of ultrasonographic arguments encompassing a valvular vegetation with new onset of mitral regurgitation associated with fever. A thoraco abdomino pelvic and plain brain computed tomography scan were performed to assess the extent of the infection and were initially negative. The patient was managed with intra venous antibiotics: ampicillin, oxacillin and gentamycin and was operated three days after his admission. He underwent a mitral valve replacement and septal myomectomy. The evolution was marked by clinical status improvement with apyrexia, regression of the biological inflammatory syndrome and disappearance of the sub-aortic gradient and mitral regurgitation. On day 7 of hospitalization, the patient suddenly developed convulsions. An urgent non contrast brain computed tomography revealed left frontal intra axial hematoma with intra ventricular and subarachnoid hemorrhage along with diffuse brain edema, subfalcine and left uncal herniation as shown in Figure 6.

Brain CT angiography demonstrated left middle cerebral artery distal M1 segment saccular aneurysm formation with irregular and lobulated contours as shown in Figure 7.

DISCUSSION

Information on patients with HCM who develop IE is limited to isolated case reports and small case series. Nevertheless, the incidence of endocarditis among these particular patients is reportedly 18 to 28 times higher than in the general population with the true incidence of IE is unknown in children with HCM, however worse prognosis was reported in cases of IE with HCM than in IE alone or with congenital heart disease.

The most cited study was that of Spirito, et al. who followed the evolution of 810 patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and the incidence was reported to be 1.4 cases per 1000 person-years, the main risk factors were left ventricular outflow obstruction and left atrial dilatation. The mitral valve was the most affected. The occurrence of infective endocarditis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients was explained by endocardial lesions secondary to turbulent flow during ejection and contact between the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve and the septum during systole which is called « Venturi effect », thus direct trauma resulting from septal-anterior mitral leaflet contact may predispose to infection and vegetation formation.

We note that the vegetation in our case was indeed located at the anterior leaflet of mitral valve. Dominguez, et al. queried a prospective infectious endocarditis cohort from 27 Spanish hospitals and identified 34 cases with underlying hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and they found that both the aortic and mitral valves were affected with left ventricular outflow obstruction detected in 50% of cases.

The most common germs found in these studies were staphylococcus aureus and streptococcus with this latest being more found among native-valve hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients. The germ in our case was not identified with blood culture remaining negative.

Sims, et al. reported in a retrospective cohort of 30 patients at Mayo clinic Rochester that there were similar rates of both mitral and aortic valve involvement regardless the presence of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction with symptomatic embolic complications occurred in 33% of cases and could impact the disease prognosis.

Our patient was at high risk of neurologic complications, due to large size of the mitral valve vegetation and left heart involvement.

Lee, et al. reported a paediatric case of a 15-year-old girl with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy who developed infectious endocarditis in the left ventricular outflow tract in subaortic region and underwent surgical intervention due to systemic embolization and persistent fever. Another Chinese study of Wang, et al. showed that the proportion of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients with infective endocarditis was 0.19% with the estimated incidence of 0.15/1000 person-years in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients.

Morgan-Hughes and Motwani reported an isolated case of mitral valve endocarditis with asymptomatic obstructive HCM in a young adult patient and suggested that mitral endocarditis complicating HCM occurs predominantly on the left ventricular aspect of the anterior mitral valve leaflet in the presence of outflow tract obstruction with estimated probability of developing endocarditis in patients with obstruction < 5% and a worse prognosis of IE if there is underlying HCM.

Mitral valve replacement surgery and septal myomectomy are the two accepted therapeutic methods for symptomatic obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy refractory to medical treatment but the larger series on the surgical treatment suggested that the two operations were rarely combined. We recall that our patient had both operations at the same time due to severe mitral regurgitation.

According to Jacobwitz, et al., nearly 40% of children with infective endocarditis had neurologic complications. Larger left sided lesions on the mitral valve are more likely to embolize as in our case. The occurrence of a complication such as rupture of an intracerebral mycotic aneurysm as was the case in our patient, is very rare and limited to a few isolated cases reported in the literature.

CONCLUSION

Our new case highlighted the emerging role of HCM in infective endocarditis in paediatrics with intercurrent neurologic complications could significantly impact the patient’s prognosis despite challenging treatment.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Vicent L, Luna R, Martínez-Sellés M. Pediatric Infective Endocarditis: A Literature Review. J Clin Med. Jun 5 2022;11(11) doi:10.3390/jcm11113217

- Mahony M, Lean D, Pham L, et al. Infective Endocarditis in Children in Queensland, Australia: Epidemiology, Clinical Features and Outcome. Pediatr Infect Dis J. Jul 1 2021;40(7):617–622. doi:10.1097/inf.0000000000003110

- Carceller A, Lebel MH, Larose G, Boutin C. New trends in pediatric endocarditis. 10.1157/13080402. Anales de Pediatría (English Edition). 2005;63(5):396–402. doi:10.1157/13080402

- Somendra S, Mehrotra S, Barwad P, Gupta H, Bahl A. Incidence of infective endocarditis in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Indian Heart J. Nov–Dec 2024;76(6):405–407. doi:10.1016/j.ihj.2024.11.332

- Nandi D, Hayes EA, Wang Y, Jerrell JM. Epidemiology of Pediatric Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in a 10-Year Medicaid Cohort. Pediatr Cardiol. Jan 2021;42(1):210–214. doi:10.1007/s00246-020-02472-2

- Richard P, Charron P, Carrier L, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: distribution of disease genes, spectrum of mutations, and implications for a molecular diagnosis strategy. Circulation. May 6 2003;107(17):2227–32. doi:10.1161/01.Cir.0000066323.15244.54

- Maron BJ, Maron MS. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lancet. Jan 19 2013;381(9862):242–55. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60397-3

- Colan SD. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in childhood. Heart Fail Clin. Oct 2010;6(4):433–44, vii–iii. doi:10.1016/j.hfc.2010.05.004

- Desnos M. [Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: current aspects and new developments]. Bull Acad Natl Med. Apr–May 2012;196(4-5):997–1009; discussion 1009–10. Cardiomyopathie hypertrophique: aspects actuels et nouveautés.

- Eldadah O, Tuwayjiri AKA, Alotayk HS, Salem MM, Alharbi NM, Alhammad RA. Overview of epidemiology and management hypertrophic cardiomyopathy among children. Journal of Clinical Images and Medical Case Reports. 01/29 2024;5(1)

- Maron BJ. Clinical Course and Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. Aug 16 2018;379(7):655–668. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1710575

- Natsheh Z, Rajabi M, Shrateh ON, Bassal SI. Unique clinical entity: Infective endocarditis with ruptured MCA mycotic aneurysm presented as fever of unknown origin: Case report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. Nov 2023;112:109000. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2023.109000

- Carrel T. Commentary: Endocarditis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A reason to strengthen the guidelines? JTCVS Tech. Dec 2020;4:286–287. doi:10.1016/j.xjtc.2020.10.046

- Alessandri N, Pannarale G, del Monte F, Moretti F, Marino B, Reale A. Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy and infective endocarditis: a report of seven cases and a review of the literature. Eur Heart J. Nov 1990;11(11):1041–8. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a059632

- Spirito P, Rapezzi C, Bellone P, et al. Infective endocarditis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: prevalence, incidence, and indications for antibiotic prophylaxis. Circulation. Apr 27 1999;99(16):2132–7. doi:10.1161/01.cir.99.16.2132

- Dominguez F, Ramos A, Bouza E, et al. Infective endocarditis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A multicenter, prospective, cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). Jun 2016;95(26):e4008. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000004008

- Sims JR, Anavekar NS, Bhatia S, et al. Clinical, Radiographic, and Microbiologic Features of Infective Endocarditis in Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. Feb 15 2018;121(4):480–484. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.11.010

- Lee ME, Kemna M, Schultz AH, McMullan DM. A rare pediatric case of left ventricular outflow tract infective endocarditis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. JTCVS Tech. Dec 2020;4:281–282. doi:10.1016/j.xjtc.2020.09.019

- Wang P, Song L, Gao XJ, Wang SY, Song YH, Qiao SB. [Clinical analysis of 14 infective endocarditis in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy]. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. Dec 1 2020;59(12):982–986. doi:10.3760/cma.j.cn112138-20200104-00003

- Morgan-Hughes G, Motwani J. Mitral valve endocarditis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: case report and literature review. Heart. Jun 2002;87(6):e8. doi:10.1136/heart.87.6.e8

- Wu ZW, Yan H. Infective endocarditis in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a case series and literature review. Chin Med J (Engl). Dec 14 2020;134(9):1125–1126. doi:10.1097/cm9.0000000000001265

- Jacobwitz M, Favilla E, Patel A, et al. Neurologic complications of infective endocarditis in children. Cardiol Young. Mar 2023;33(3):463–472. doi:10.1017/s1047951122001159