Innovative Anatomy Instruction for Medical Education

Milestones in the Pedagogy of Anatomy Instruction in Medical and Graduate Education

Orien L. Tulp1,2, Frantz Sainvil1, Hailin Wu1,2, Andrew Sciranka1, Syed A A Rizvi1,3, and Rolando Branly1,2

- Orien L. Tulp Colleges of Medicine and Graduate Studies, University of Science Arts and Technology, Montserrat, British West Indies; East-West College of Natural Medicine, Sarasota, FL, USA

- Frantz Sainvil Colleges of Medicine and Graduate Studies, University of Science Arts and Technology, Montserrat, British West Indies

- Hailin Wu Colleges of Medicine and Graduate Studies, University of Science Arts and Technology, Montserrat, British West Indies; East-West College of Natural Medicine, Sarasota, FL, USA

- Andrew Sciranka Colleges of Medicine and Graduate Studies, University of Science Arts and Technology, Montserrat, British West Indies

- Syed A. A. Rizvi Colleges of Medicine and Graduate Studies, University of Science Arts and Technology, Montserrat, British West Indies; Larkin University, Miami FL, USA.

- Rolando Branly Colleges of Medicine and Graduate Studies, University of Science Arts and Technology, Montserrat, British West Indies; East-West College of Natural Medicine, Sarasota, FL, USA

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED:31 May 2025

CITATION:TULP, Orien L. et al. Milestones in the Pedagogy of Anatomy Instruction in Medical and Graduate Education. Medical Research Archives, [S.l.], v. 13, n. 5, may 2025. Available at: <https://esmed.org/MRA/mra/article/view/6517>.

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i5.6517

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

A brief description is presented of an integrated approach in the emerging pedagogy of human anatomy instruction that incorporates elements of both classical didactic classroom and small group virtual instruction in human anatomy, neurobiology and pathophysiology and culminates in an advanced cadaveric dissection exercise using fresh, unembalmed cadavers in a small group, surgical theatre setting. The small group cadaveric demonstrations and discussions focus not only on classical structural and diagnostic nomenclature but also include patient oriented medical and surgical techniques and procedures, in addition to topics of pathophysiologic and biomedical significance. The integrated sequence, where class size is necessarily progressively staged downward from larger classroom settings to the small group mentored cadaveric setting capitalizes on the strengths of each instructional component, and encourages greater instructor-student interactions at each level. The structured approach fosters effective student retention of anatomic concepts programmed toward essential later modules in basic and clinical science years and assures physician and scientist competency to standard upon completion of their academic studies. Thus, the purpose of the current review was to improve the effectiveness and student comprehension of anatomy instruction by incorporating emerging technological advancements including virtual, computer assisted modules and focused, small group cadaveric dissections from a pathophysiology perspective into the instructional format. This modernized pedagogical approach was universally well accepted by medical and graduate students in attendance.

Keywords

Anatomy; cadaveric dissection; prosection; virtual dissection; clinical integration; COVID-19 pandemic; fiberoptic examination; surface anatomy; historical perspectives.

Introduction

Because of the obvious inclusion of the tenants of human anatomy that form core foundational applications for clinical medicine, a comprehensive knowledge of anatomy and its physiological significance has contributed to a longstanding pivotal role in the milestones of medical and biomedical education for many generations of physicians and biomedical scientists. Thus, with advancements in the science and technology of modern, current day medicine and the state of molecular biology, its continued place in the medical and graduate school curriculum deserves careful attention to remain current. While the global shutdowns imposed by the recent pandemic in addition to the environmental threats of a tropical, volcanic island environment have imposed additional stress and limitations on the format and pedagogy for gross anatomy and other biomedical course modules, the crisis necessitated a review, reinvention and rediscovery of effective instructional platforms and pedagogic formats to accomplish an effective anatomy program without losing sight of the core objectives of the academic modules in medical and graduate education. With a seemingly greater focus on expanded modules in molecular biology, emerging pharmacotherapeutics and pathophysiology applications have resulted in a condensation and apparent erosion of much of the previously allotted classroom and laboratory hours in the gross anatomy curriculum in many institutions.

To this end, technologic advancements including applications of virtual anatomy lecture and dissection elements, incorporation of computer simulations of physiologic and neurophysiologic processes, combined with small group dissections have been developed in an attempt to maintain academic excellence in the face of hopefully transient adversity. The overriding emphasis focuses on relevant clinical, surgical, and biomedical applications that have been integrated into the anatomy/biomedical science curriculum. All laboratory dissections were conducted in fresh, non-embalmed cadavers over a compressed time allotment, and which ultimately markedly enhanced a clinical emphasis in addition to greatly improved student acceptance compared to dissecting embalmed specimens or artificial models. Institutional financial constraints may offer additional benefits as a decreasing availability of cadavers has occurred due to insufficient cadaver donations to support gross anatomy dissection labs over recent decades has also occurred in some locations, thereby making it imperative to gain the greatest productivity of a relatively scarce instructional commodity. The innovative, clinically focused cadaveric anatomy program summarized in this correspondence has improved the delivery, content, and retention of anatomic principles for medical and graduate students and has become one of the most popular modules offered with numerous students requesting additional modules.

Because the revised clinically oriented curriculum and has been deemed highly relevant to current medical education and graduate studies, students often participate in additional models for extra credit. The advancements in the anatomy curriculum pedagogy and experience demonstrated purpose for content retention and have not only enabled students to retain essential anatomic content more firmly but improved the overall interest in the importance of anatomy and anatomic functions as an essential component of their medical and biomedical education. The small group discussions focus not only on structural nomenclature but include topics of pathophysiologic and biomedical significance. An additional primary objective was to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of delivery as a major consideration in the development of the revised curriculum, in addition to enhancing the overall interest and significance to the field of anatomy and its manifestations. The revisions incorporated a renewed focus on the clinical and biomedical relevance of each system examined. As a result, the anatomy dissection module transitioned to become one of the most sought-after components of the first-year medical and graduate basic sciences portion of the medical curriculum and surpassed the student retention and cost-effectiveness of the traditional anatomy laboratory course. The program developed proved to be a successful resolution due to adverse environmental conditions that precluded a traditional, multisegmented anatomy dissection program. Cadaveric anatomy dissection continues to contribute to a pivotal and essential component of the fundamentals of anatomy education in medical, veterinary and graduate education in the biomedical sciences. Because of adverse environmental conditions due to ongoing volcanic eruptions, it became essential to develop an alternative to the traditional academic program, including cadaveric dissections. Historically, much of the training of early physicians occurred through apprenticeships mentored by more senior physicians, who could instruct their level of understanding of the state of medical sciences then known. Since the emergence of the modern era of the 20th and 21st centuries, advancements in technological innovations combined with advancements and a burgeoning volume of medical applications in the physical sciences, molecular and biological sciences have vastly expanded the mass, scope and volume of medical and graduate education. Accordingly, the vast volume of information deemed essential for the emerging physician and medical scientist to succeed has necessitated major changes and redistribution of focus, priority, and a creative selection and scheduling of which subjects may be considered the most essential for timely inclusion in the curriculum. The ultimate progression now includes integrated modules of didactic, virtual and laboratory based cadaveric dissection. While the allocations of instructional time, resource availability, and educational principles may have become redistributed, the objectives for the emerging physician, surgeon, and biomedical scientist to achieve competency in gross anatomy remain strong and have changed little over the ensuing generations since their embryonic contributions and milestones were first introduced in Padua and Salerno many generations ago and extending to the present day.

Since the earliest recorded history, physicians have been curious and inquisitive about the functions of the human body, and speculated regarding their relationships with illness and disease, albeit often with little scientific evidence to support their early theories. Since ancient times, the practice of anatomic cadaveric dissection was long considered an essential component and an early necessary milestone in the medical education of aspiring physicians and biomedical scientists. Among the earliest recorded history of medical education as recorded in Salerno and ancient Egypt, cadaveric dissection originated as a religious ritual that was deemed a required rite of passage to the kingdom of the dead.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES IN ANATOMY INSTRUCTION

Among the earliest milestones in anatomy education are the origination of the anatomical theatres in Padua (1490) and Bologna (1637), established during the Renaissance period. Gross anatomy dissection was soon to become considered to be an essential albeit artistic and spiritual exploration of the life, suffering, and death of the deceased although the actual causations of death were then virtually unknown. Anatomists soon began to dissect cadavers more extensively in attempts to define the structures of the body and produced early sketches and texts that illustrated the visual images that were based on their dissections. In addition, structural and pathological variations observed might be noted, with only speculative suggestions for the presence of atypia. The modern era of scientific aspects of human anatomy was highlighted by the publication of a series of texts by Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564), a Flemish physician and anatomist, the youngest of three generations of physicians, and who is still considered prominent among the real fathers and ancestors of the scientific nature of modern anatomy as we know it today. Vesalius utilized anatomy dissection while teaching aspiring medical students, and published De Humani Corporis Fabrica (7 volumes, from 1534), which included extensive anatomic diagrams depicting the nature, position and presumed functions of each structure and organ described. While the earlier teachings and writings of Galen (De usu partium corporis humani) focused on a humoral theory had been considered unassailable at the time, Vesalius based his philosophy on factual observations and which often disputed and expanded elements of Galen’s writings. Vesalius claimed that practicing medicine had three main aspects still accepted today, including medications, diet, and ‘the use of the physician’s hands in treating illness. His teachings suggested knowledge of anatomy and physiology gained through dissection as essential constituents in the training and education of physicians. In the 17th Century, William Harvey, having studied under the leading physicians of his day, developed and applied available scientific research methods of the day to discover the basis of the circulation of blood. Harvey’s work proved that the heart and blood vessels were connected as a single physiologic system, and published the first of several key publications on the subject (Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus [Anatomical Exercise on the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals] An Anatomical Disquisition On the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals (1628; 1653 in English), thereby marking yet an additional milestone in his era of scientific advancement. His fundamental observations contributed critical new knowledge to the emerging sciences of anatomy and physiology upon which many additional studies would be based, and which contributions are still referenced in present day medical physiology textbooks.

MILESTONES OF PROGRESS

The next significant milestone occurred In the 17th century. The renowned Dutch physician, surgeon, and Praelector in Anatomy, and public figure Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (9 October 1593 – 12 September 1674). Dr. Tulp was noted for his strong moral character, extraordinary civic commitment, mentoring of apprentices, and his renowned medical skills, having also been appointed as physician to many leading figures of the day. Dr. Nicholaes Tulp was also the mayor of Amsterdam, and among his many assigned duties and responsibilities were to regularize public dissections and to apprentice new surgeons by the Amsterdam Guild of Surgeons (i.e., the, Surgeons’ Guild). In early 1632, Dr. Tulp engaged a young, fledgling and relatively unknown artist in his early 20s, Rembrandt van Rijn, (i.e., a then fledgling artist we now recognize as Rembrandt) to paint his now famous rendition of cadaveric dissection. The artwork was entitled ‘The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Tulp’. Renditions of his painting now adorn most modern anatomy textbooks and anatomy departments worldwide. Thankfully, while the instructional formats for anatomy dissection demonstrated by Dr. Tulp would continue as the standard reference for dissection anatomy for the next two centuries. Ultimately, the teaching of anatomy would enjoy many advances and additional milestones in pedagogy and process since that time. Nevertheless, the basics displayed by Dr Tulp in January, 1632 continue to remain important in today’s discussion. The 18th to the 20th century saw a large expansion of medical schools throughout most countries of the world, each with their own model of inclusion of cadaveric dissection. These progressions in the pedagogy of anatomy instruction eventually paved the way forward to a greater reliance on scientific aspects of continuing discoveries and anatomic discussions. Indications of religious overtones were sometimes noted in those early years of medical education, as cadaveric skeletal remains have recently been unearthed in Cambridge MA Holden Chapel and others, then the sites of early US medical schools. Dissection instrumentation and decorum was similar to the often rudimentary surgeons’ tools of the day and have undergone vast improvements to the present day where it now may resemble a modern surgical theatre with an expanded capacity of multiple cadavers simultaneously to accommodate the larger numbers of medical students now common to most Institutions. However, as an outcome of the recent global Covid-19 pandemic, the incorporation of alternative strategies in the modernization and reorganization of anatomy curricula have necessarily placed increasing economic and didactic pressures on previously existing curricular models at many institutions. However, the advances in anatomic curricula have not outpaced the need for some back to the basic’s fundamental skills often initially developed in dissection. Specialized, regional dissection is still what most practicing surgeons and anatomists do best and may require more than just textbook and virtual illustrations for the developing practitioner or budding surgeon to excel in their emerging career.

STANDARDIZATION OF ANATOMY NOMENCLATURE

The historical progressive emergence of anatomic nomenclature developments represented a pivotal milestone that extended over multiple centuries in the art and science of anatomy. In the recent past decades, with the publication of many additional chronicles in medical education, combined with more recent technological advances in virtual technology, countless additional milestones in the progressive stages of anatomy education have occurred since the time of Galen and others. Over the course of the past five centuries there was considerable conflicting terminology with regard to the standardization of nomenclature of anatomic structures, resulting in often confusing multiple designations for the same structures as they may have been named by many anatomists of different institutions. Among the oldest treatises on anatomy were those of Galen, who used colloquial Greek wordings to describe major anatomic structures. In the 16th century, Dr Andreas Vesalius expanded the state of the art of anatomy with detailed illustrations he published in De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem, in Latin. (1543; updated version including English ~1553) and which would become a standard reference forerunner of later attempts to standardize anatomy nomenclature. Vesalius devised a system that distinguished anatomical structures with ordinal numbers. Although he did not coin specific anatomic terms per se, his detailed illustrations helped to condense the redundancy created by multiple terms in earlier use that were intended to describe the same structure. Vesalius illustrations marked the onset of several attempts by anatomical societies conferring periodically for over two centuries to further resolve and eliminate redundant terms and initiate a standardized terminology. Those efforts resulted in several earlier iterations of anatomic nomenclature, ultimately reducing some 50,000 terms previously used by different societies to a mere approximate 5500 items. Professors Sylvus (Paris) and Bauhin (Basel) contributed to the next (third) stage in anatomic nomenclature development in the 16th century with the addition of the identity of muscles, blood vessels and nerves to the anatomic descriptions. An early attempt to modernize and standardize nomenclature was finally made with the publication of Basle Nomina Anatomica (1895). Numerous anatomical groups have continued to develop standardization for another century. The anatomical terminology has been revised repeatedly until the initial edition of Terminologia anatomica (TA1) was first published both in Latin and English in 1998. Since TA1, further advancements in anatomical nomenclature have become the standardized language used to describe the human body’s structures and features, ensuring clear and precise communication among medical professionals. The most recent and current standard is the “Terminologia Anatomica” (TA), a comprehensive list of anatomical terms and definitions. Current nomenclature identifies the direction, (i.e., superior, proximal, dorsal, ventral, etc.) and functions of the structure being described, with most structures in latinized terms. Terminologia Anatomica (TA) developed by the Federative International Programme on Anatomical Terminology, a program of the International Federation of Associations of Anatomists is published in both Latin and English, including an ebook form since 2021. The TA currently contains a total of 7112 numbered items and has now been established as the International standard for human anatomical terminology as used in medical and biomedical education worldwide. The anatomical terminology was revised repeatedly until the current Terminologia anatomica was published in both in Latin and English. With this terminology, the practicing physician may determine with great confidence the exact location of pathophysiologic features when reviewing diagnostic reports. The recent developments in molecular biology have introduced additional terms, independent of those in the TA, and which have specific applications assigned to specialized areas of molecular biology and scientific endeavor.

RESTRUCTURING OF THE ANATOMY CURRICULUM

Only a few decades ago, the traditional delivery of the gross anatomy courses in medical and graduate education in many institutions often consisted of 10 or more semester credit hours conducted over 2 or more semesters, consisting of some 300+ clock hours distributed over the full academic year of the curriculum. Remnants of the centuries-old approaches in cadaveric dissection continued to persist throughout the 19th and 20th century. However, recent constraints on previously dedicated clock hours for the entire core course have now often been reduced to a single semester with many fewer semester and clock hours than historically committed at many institutions. The reduction of curriculum allotments enabled additional lecture hours to become available for other topics, and thus have thereby enabled a greater accommodation for advanced topics in molecular and cell biology, pharmaceutics, and expansion of medically relevant physiology studies among other timely topics often deemed critical for entry into a modern medical practice setting. In an attempt to provide guidance to decision-makers involved in clinical anatomy curriculum development at the medical school level, the Educational Affairs Committee of the American Association of Clinical Anatomists (AACA) recently developed a document which defines the general contours of a gross anatomy curriculum designed to lead to a medical degree. The main body of the document established the anatomical concepts as well as the subject matter that a student should master prior to graduation from medical school. Gross anatomy dissection, however, is still a crucial primary core topic in medical school and biomedical graduate studies. With newfound advancements in the effectiveness of pedagogical applications, including computer generated topic content, greater retention of that anatomic knowledge and its clinical and biomedical applications well into the clinical practice years was envisioned. The nature and content of gross anatomy, which was historically regarded as a primary core course in biomedical education in medical (MBBS, MD, DO, and some PhD and Graduate) curricula as well as in other disciplines of selective graduate education and non-allopathic medical programs. These programs were significantly and severely impacted by emerging challenges in the pedagogy of delivering medical education during the recent pandemic years. The mandated lockdowns impacted many areas of education at all levels, including medical and graduate education. Restriction limitations imposed on maximum group size and social distancing enabled development of innovative reexamination and restructuring in the delivery of instructional modules in aspects of both didactic and gross dissection activities focused heavily on small group settings. Moreover, the travel and public assembly restrictions forced by the pandemic also facilitated the adoption of off-campus modules for much of the traditional lecture content, thereby limiting the opportunities for the in house, cadaveric dissection element of the instruction. This mandated adjustments that included substantial reduction in both didactic lecture availability and the time proven laboratory dissections that were once a major core course and the major hallmark of the first-year medical student’s and some graduate student’s academic pursuits. The results were that the role of gross anatomy as a core course in the medical curriculum has been forced to undergo a much needed and welcome transition in scope and content in many institutions around the globe based on a variety of economic, epidemiological, and other factors. In contrast, the academic expectations for minimum student comprehension in anatomically based topics remained materially unchanged, while obligations in molecular science and other topics now deemed essential for the practicing physician and biomedical scientist expanded.

INTRODUCTION OF THE PERSONAL COMPUTER IN MEDICAL AND GRADUATE EDUCATION

The most recent milestone in anatomy education has occurred courtesy of the advent of the personal computer generation entry into the realm of educational advancement and which has progressed rapidly over only the past ~ 5 decades. Since the early 1980s, the introduction of the personal computer (PC) has been introduced into the university classroom, catching many senior faculty whose careers did not include computerization of lectures and related computer-generated academic activities off-guard. While supercomputers had made their entry and had been utilized for data analysis for over a decade, development and programming of the word-based programs needed for instructional applications remained in their infancy. Add to that the development, availability and access to the modernized internet in recent decades has further contributed to additional changes and advances in formats of educational pedagogy. Now not only can the lectures be attended anywhere on the planet where internet access is available, but the student census attending an internet classroom is virtually unlimited from comparatively small groups to hundreds of participants, and thus no longer limited to the seating confines of the physical classroom of the days gone by of yesteryear. Thus, with the great advancements in educational technology that have evolved in the PC age, the potential for innovation in the delivery of didactic lecture and topic discussion can be expanded as far as the imagination can envision. Moreover, introduction to computers in education now occurs in early childhood, often before or during the earliest years of one’s primary school education, with likely expectations that such virtual classroom experiences may continue well into the highest levels of collegiate education including medical and graduate education and beyond. The enormous volume of information readily available on the internet is now virtually unlimited and continues to expand exponentially with each passing year as new information is developed and incorporated into the virtual stacks. While the time proven traditional textbook often previously provided the grounding for many academic courses, most leading textbooks can now also be readily acquired via renting or purchase as ebooks, thereby further expanding their applications to higher education in remote settings. Research of topics that once may have required multiple trips to the traditional library stacks can now often be reduced to minutes via 24/7 access to a Google search engine, with the result that greater volumes of relevant information may be accessed in less time, a decided advantage for the aspiring medical or graduate student. Moreover, the internet stacks now extend to decades old publications, enabling the inquisitive student to gain an appreciation for the progressive advances and their integration into their fields of interest over time.

ESTABLISHING A CLINICAL FOCUS IN ANATOMY EDUCATION

In recent decades the overall content and complexity and necessity-driven objectives toward a more clinically-oriented focus of basic medical sciences in medical and biomedical curricula have emerged in the current milestone of anatomy curricula. The necessity for broad, progressive updates and topic integration has now assumed an unprecedented urgency in an ongoing modernization of curriculum development to better support the academic needs of students in an ever-expanding body of medical and scientific knowledge. Because a fewer number of the generous clock hours previously allocated for gross anatomy instruction still remain available, the necessity for a close review of the most essential topics, critical course content and compressed time allotment for laboratory sessions are now imminent and has paved the way for the integration of computer-generated technology to come to the rescue. It is noteworthy that the overall subject content, depth of instruction and student comprehension in the developing current curricular models has not diminished, while academic expectations imposed on the student have likely increased. If anything, the overall content has not only maintained its overwhelming criticality in importance, but it has also increased in its complexity in its potential clinical and biomedical applications. Therefore, a driving need exists to condense such courses into shorter time frames and clock hours of participation to the extent possible. These benefits may be attained by making more efficient use of resources to include the incorporation of a stronger clinical focus by strategically integrating computer-assisted virtual applications, simulation exercises, 3-D modeling, problem-based learning (PBL) approaches, and by adding a presurgical approach to the laboratory modules by including surgical theatre demeanor and clinically relevant procedures. The net result of the above is geared toward providing a stronger and more appropriate instructional program that is more closely related to the current time, period, and circumstances of contemporary interest. By offering more relevant content and technologically enhanced quality of medical education an institution may better meet the challenges and success on qualifying examinations the future may present to the new medical or bioscience graduate.

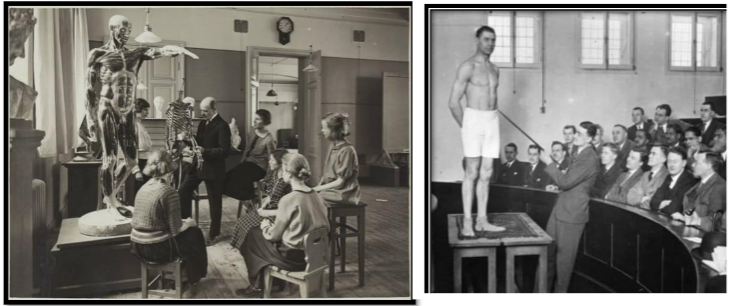

INTRODUCTION TO SURFACE ANATOMY AND THE PHYSICAL EXAM

Mastery of surface anatomy is an essential skill in medical practice, regardless of the medical specialty selected. The general physical examination is among the most common medical examination conducted worldwide in Industrialized society for many generations and is dependent on a solid comprehension of surface anatomy by providers in many specialties and medical career fields. Thus, the early introduction of concepts of surface anatomy is an important prerequisite to the dissection laboratory, including descriptive anatomic terminology. A comprehensive mastery of surface anatomy and its clinical ramifications is a fundamental clinical tool in medical practice, where it serves to identify regional clinical markers. Surface anatomy is especially essential in Eastern Medicine and physical therapy, as trigger points, meridian locations and neuromuscular networks are exacting locations. A brief overview of surface anatomy terminology is also invaluable in preparing students for future clinical modules, including introduction to the conduct of the physical examination of a patient, nor is it lost in most qualification examinations. The physician normally conducts physical examinations along generally standardized systematic procedures, rather than by random unrelated snippets here or there. The systematic body plan approach ensures that the nature of the examination can be comprehensive and less likely to miss important diagnostic findings. A common exception is when the clinical setting dictates a targeted examination, to address a specific regionally localized symptom, i.e like a chief complaint of a ‘sore throat’ or other acute patient episode, and where time and resource constraints may influence the timing and extent of further examination. The recording of the vital signs in concert with a targeted exam are nearly always a first step in most examinations and may provide an indicator to the clinician for subsequent targeted regional or systemic review. In allied healthcare professions, comprehension is an equally important element in patient diagnosis and care. Introduction to the cadaver provides an excellent orientation for the students first ‘hands-on’ opportunity to examine their first patient, regardless of the career path in primary care or ancillary careers they may be embarking on. The introduction to surface anatomy is ideally delivered via computer power point presentation via classroom or SPOC format, followed by full body anatomic models and human models. Thus, the concept and importance of surface anatomy is readily introduced by virtual slide presentations in live or remote classroom settings and augmented by the recruitment of simulated or live models in the active classroom. Figure 2B below depicts a traditional early example of introducing surface anatomy, where particular regions and body planes could be pointed out visually by the instructor. During the past two decades however, the concept of body painting and point delineation via markers in illustrating salient features of bodily surface features has advanced considerably, further reinforcing the old adage that ‘a picture is worth a thousand words’ especially when the students apply the surface markings in the picture or live model. In addition, live models can also enable students to learn techniques of palpation, to further identify surface and underlying features as they commonly apply to a physical examination of a patient. Major organs can often be located and generally assessed by palpation, thereby contributing to physical diagnosis. In practice, surgeons often may apply surface body markings during their diagnostic examinations to clarify and define the intended surgical field and to further assist the surgical staff when applying drapes surrounding the intended surgical field. Such body markings are not permanent and help to reduce potential surgical errors should the drapes be applied incorrectly.

ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS IMPOSED CHANGES IN PEDAGOGY OF MEDICAL EDUCATION

In the British Island Territory of Montserrat, an additional urgency developed in 2003 at the university and at other local schools with the continuing re-eruptions of the long silent Soufriere Hills Volcano. The severe impact on environmental and climactic issues, in addition to posing potential damaging health concerns throughout the region became urgent, disrupting all local activities, and forcing mass evacuations for much of the population. Volcanic ash, once it becomes airbound consists of fine abrasive microparticles that can impact deep within the lungs when inhaled, in addition to the caustic acidic vapors emanating from the volcano. The volcanic cloud attained heights of up to ~7 miles in the atmosphere and fell to earth over a broad swath of Montserrat and nearby sea- and land masses. This included the university campus located only ~5 miles distant from the volcano and located well within the prevailing wind patterns. Thus, continued delivery of academic and laboratory sessions became urgently compromised, and evacuations of all students and otherwise non-essential residents were encouraged by Government officials, resulting in over half the population leaving the island for safer domains. This created an urgent need to transition all lecture modules to an instructionally secure, IT-based small platform online course (SPOC) delivery format, including the didactic element of the anatomy lectures. The conversion in lecture delivery format minimized the direct impact of the volcanic disruption and inconvenience on the academic progress of students. In accordance with the University charter, instructional modules including the anatomy laboratory were relocated to a safe and more accessible environment off-campus, which contributed to the redevelopment of this essential laboratory experience as is outlined below.

SMALL PLATFORM ONLINE COURSE (SPOC) DEVELOPMENT

To achieve the above objectives effectively, the resulting course and laboratory content must be presented in the most imaginative and cost-effective manner possible while remaining within the available time and cost constraints. The delivery modules must accommodate decentralization, with some modules presented via SPOC, and others as dynamic, hands-on, small group dissection exercises. Instructional and examination security was insured via issuance of individual passcodes for attendance and IPS tracking and video confirmation for additional identity confirmation. Classes were organized such that students would be able to complete their primary medical or graduate qualification and subsequent graduation from medical or graduate school within the current 4 or more years, without sacrificing essential course content or satisfactory mastery of the subject matter. All previously developed classroom lecture modules were refocused with the SPOC format, which also enabled review and updates as appropriate, including a list of both historical and current references including new findings pertinent to the particular module. In addition, multiple sections of a course could now be consolidated into a single larger live lecture to include both remote and classroom students, further insuring all participants received the same information during a lecture. During such lectures, students are encouraged to make comments or ask questions to clarify an item of interest.

INTRODUCTION OF VIRTUAL ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY MODULES

To accomplish these objectives, the didactic lectures were integrated with elements of both virtual and active live faculty interactions. The onset of computer-based anatomy occurred in rudimentary form several decades ago, thus forming a basis for further refinement in the virtual pedagogy of anatomy. An organ system-based format where anatomic, diagnostic, and therapeutic topics are integrated enables quasi-compartmentalization of topic contents. This compartmentalization within the whole approach has been shown to produce an effective academic medium to satisfy these objectives, while encouraging enhanced student participation and retention of the subject matter discussed to academic standards. Lectures may be enhanced by a virtual anatomy system such as Anatomage® or similar virtual instructional assist and organized with a clinically oriented problem-based learning (PBL approach) in a small group setting for maximum student participation. The virtual component included opportunities for students to test their knowledge of anatomic structures and function via self-testing, in addition to modelling pharmacotherapeutic interactions and neurophysiologic phenomena. The program should best identify a defined clinical focus and clear objectives and the end points in mind for each module in the syllabus. With the virtual approach, both physiologic, neurophysiologic and biochemical material in addition to pharmacologic applications may be integrated in many available virtual program formats. Discussions are best conducted in small comfortable groups, where interparticipant communications and uninhibited instructional mentor interactions may develop spontaneously. A typical faculty to student ratio approximating 8:1 or less has been observed to be an effective group size, and can insure that every student’s question may be examined in an accurate and respectful manner. The small, intimate group setting, where no question is considered a bad question, the topic may be thoughtfully addressed, and is thus likely to encourage optimal student faculty interactions when discussing critical points during the dissection activity.

APPLICATION OF THE SPOC CONCEPT TO LIVE AND VIRTUAL MODULES

Among the presentation topics to be considered for selection with a SPOC format include topics in Pathophysiology, Medical Biophysics, Medical Epidemiology, and preclinical introduction to selected clinical procedures. The discussions may be integrated where appropriate to enable further broadening the scope of the lesson to include other areas of allopathic and natural medicine as may be applied to healthcare. Upon completion of the dissection exercises, each student is expected to be able to demonstrate the above procedures to a defined standard, including a complete functional surgical dissection and reassembly, in addition to other ancillary techniques such as suturing and forensic observations. The above are often best accomplished with non-embalmed cadavers in their natural state, which can add additional realism and clinical focus to the process. The anatomic content may be reinforced and revisited in subsequent years in the basic science and clinical modules of the curriculum. With careful attention to planning, and adherence to the curriculum one can likely fulfill the needs of tomorrow’s medical practitioners, surgeons, physicians, and biomedical scientists; with careful attention to content and need. To accomplish the academic challenges successfully will require the undeterred will and motivation of a dedicated faculty and staff, and the availability of emerging educational technologies and resources now available. With such resources in mind, one can help to attain and maintain the challenge that will enable the students of today and tomorrow to master the field of anatomy, physiology, neurobiology and associated topics successfully. The recent emergence of the recent coronavirus pandemic and other endemics have now added an additional extraordinary burden to compressing the educational process by forcing compromises in classroom and laboratory participation. Moreover, once a revised curriculum has been successfully introduced, it may pose a virtually unassailable challenge to revert back to earlier iterations of the academic process. The limited availability of reliable cadavers in addition to cadaver safety issues while always a potential concern, were further impacted by the above factors, and collectively have further impacted negatively on suitable cadaver availability and potential student safety apprehensions. The greater challenges however may require reallocations of laboratory hour scheduling, in concert within the scheduled hours for some subjects that previously may have been allotted to the cadaveric dissection experience timeslots. Faculty availability to support the laboratory or lecture sessions is also becoming a pressing issue. This has occurred at least in part due to fewer available faculty with suitable expertise in anatomy since retiring faculty may not always be replaced with the same disciplines, talents, experience levels and specializations as has typically occurred in the past. As a result, adequate supervision of cadaveric dissections along with the small group discussions may also become compromised, as cadaveric labs require adequate supervision and adherence to safety concerns, thereby placing further constraints on opportunities for individualized modes of instruction where unique dissecting skills and surgical techniques may be initially gained. In contrast, a computer-based laboratory may bypass many of the safety and availability concerns noted above for at least the pre-dissection elements of the curriculum. Moreover, by incorporation of the computer-based virtual addition, the scope and cost effectiveness of the laboratory may be further improved by combining students of other relevant career fields and their interests in the virtual and cadaveric demonstrations and instruction.

DEVELOPMENTAL OBJECTIVES FOR PLANNING AN ANATOMY LABORATORY CURRICULUM

There are several key objectives one might consider in the design, conduct, and projected outcomes of anatomy instruction in the 21st century as discussed in detail elsewhere, including the 15 points suggested below:

- Determine and clarify the learning objectives at the outset of the course; include safety concerns as an essential element at all levels of the process. Anatomy laboratory is one of the most high-yield experiences students may encounter in their formative years of basic medical sciences. It is recommended to include an explanation or probable diagnosis for the cause of death when conducting the dissection, and pathophysiologic changes are often present in cadavers. Even a death that has occurred to ‘natural causes’ likely can demonstrate the pathophysiologic changes and maladies of aging.

- Determine the duration of the projected pre-dissection and dissection experiences; establish the goals one wishes to accomplish, and clarify what the desired critical endpoint should be?

- Include a relevant Clinical Focus that incorporates both medical and biomedical interests when planning and conducting the dissection laboratory.

- Identify the budget availability and limitations, as the cadaveric laboratory experiences tend to be more expensive than typical wet labs of other disciplines. Therefore, budgetary constraints must be considered well in advance and be in sync with the objectives of the course, the student needs and their interests.

- Plan the structure of the pre-dissection and dissection components such that they may continue to be relevant in later modules; identify risks, benefits, and restrictions if any, and are effectively coordinated with delivery schedule of the dissection laboratory. Include a session on introductory surface anatomy early in the planning.

- Ensure that pre-dissection students are fully prepared both academically and otherwise, as a first experience with a cadaver may be traumatic for some students. When unprepared, some students may discontinue the laboratory in such manner that may impede their continued progression in a medical or biomedical curriculum where gross anatomy is a requirement for continued study.

- Cadaveric dissection is an intense, focused experience regardless of group size, and the use of cell phones or other recording devices, and extraneous socialization are typically prohibited in cadaveric dissection settings unless specifically preapproved.

- Adherence to respectful, strict reverence to the deceased, often preceded with an appropriate celebration including a solemn preamble. All cadavers deserve sensitivity, respect, and reverence throughout the process. Some institutions engage a chaplain to assist in this objective.

- The cadaver is the central focus of interest and attraction and deserves undivided attention from all present. In addition, the inclusion of a projection screen and whiteboard at each table is virtually essential to better focus on the topics and techniques being presented and discussed, and to insure all participants can more effectively view the dissection procedures.

- Establish a safe and Professionally oriented Presurgical Atmosphere to the Dissection Exercise, with proper attention to surgical attire and individual demeanor helps to prepare the students for later clinical experiences in a clinical or surgical theater.

- Upon completion of the laboratory exercise, the student must successfully demonstrate the essential and proper Identification, pronunciation, pathophysiologic functions of each major tissue or organ group.

- Incorporate clinical examination markers and techniques noting and variations from normal and how one might describe them using accepted anatomic nomenclature. Body painting or marking may further enhance this functional aspect of the learning experience for the student, and is easily applied to cadavers to optimize the academic and learning experience.

- Incorporate additional topics of interest and discussion points such as pathophysiology, endoscopy, bronchoscopy, imaging features, and various types of suturing when and where appropriate and time permitting. Make an attempt to determine the metabolic and pathophysiologic issues present in each cadaveric specimen. Considering the pathology observed, what possible treatments might have been beneficial for this individual as a patient?

14.Summary of objectives: Upon reaching the endpoint, the student is expected to achieve clinical competency in surface and dissection anatomy. Incorporation of new and developing advances in technology of educational pedagogy can present opportunities for change; and when judiciously incorporated, it can fulfill both a need and an opportunity to introduce fresh new insights and Ideas, and to further the discussion of special features that may be discovered in each individual cadaver. The goal of the above is to enhance content retention and initiate lifelong learning to the aspiring physician or biomedical scientist.

Results

DEVELOPING THE ACADEMIC CURRICULUM IN ANATOMY, NEUROBIOLOGY AND BIOMEDICAL SCIENCES TO ACHIEVE THE INTENDED GOALS. The curriculum of anatomy and other courses of medical and graduate instruction underwent progressive revision recently, beginning in 2007-8 due to the ongoing volcanic activity in Montserrat, which created a potentially unsafe environment not only when active, but extending for days and weeks thereafter due to the hazardous nature of airborne particles of volcanic ash that continues to contaminate the areas of post eruption, often blanketing much of the island with volcanic dust and debris. Thus, safety minded campus evacuations, in combination with technological improvements in instructional methodology and educational pedagogy coincided as a nexus for seeking an alternative approach for anatomy dissection, long considered to be a fundamental and essential component of medical education. Because the advances in instructional technology have been nothing less than remarkable during the past decades beginning with the introduction and development of computer assisted technology assists in higher education, the essence of the development and implementation of the revised curriculum proved to be timely, while mitigating unknown potential environmental risks. With the emergence and continuing development of artificial intelligence (AI), additional improvements are likely imminent in educational technology applications in the future. As early as 1983, Universities and Colleges began to incorporate computer technology into higher education in the fields of engineering, science, nutrition, business and in scientific publications with the introduction of the early versions of the Apple and Microsoft platforms. Thus the computer era in higher education was well established for many didactic courses before the 21st Century, but considerable research and development of computer applications for the study of gross anatomy and its applications to physiology, nutrition, molecular biology, and neurosciences was still in its infancy. But considering that scientific need often paves the road for innovation, emphasis became focused on the more complex nature of the greater detail incumbent in application to studies of Gross anatomy applications at a level consistent with higher level studies in medical education including ADAM, then available as a McIntosh program and widely used in undergraduate programs in the allied healthcare fields. However, no matter how realistic the computerized versions may become, they have not replaced the physical approach necessary in medical education and for most surgical applications. The surgeon’s fine motor coordination and motor skills are paramount to his or her ability to conduct the sophisticated surgical procedures now common in most surgical theaters successfully. In addition, advanced diagnostic imaging skills required for the practicing radiologist or surgeon in supporting the most challenging invasive procedures with utmost precision cannot be obtained by virtual exposure alone and also require the development of hands-on skills learned only via direct experience during continued exposure. Moreover, the combined anatomic and imaging skills necessary for many of the computer-assisted procedures now commonplace such as tumor ablations, spinal surgeries, cryoablation, and other complex procedures require previously unprecedented expertise in both surgical and computer skills by the practicing physician and surgeon. Thus, the overwhelming need to incorporate the latest in computer applications and surgical finesse are paramount in developing the physicians, surgeons, and biomedical scientists of today’s and tomorrow’s surgical theater.

REPLACING THE EMBALMED CADAVER

The Anatomy dissection program summarized below developed progressively over a period of over 15+ years in advancing to its present state. The program was developed under the oversight of the State-of-the-Art Miami Anatomic Research Center, where the staff made available much of the extensive resources needed to develop the program. From the outset, only unembalmed safety tested cadavers were utilized in anatomic dissections and were maintained in a cooled and well-ventilated dissection parlor equipped with well-equipped sanitized, stainless dissection tables for use in active dissection exercises. The use of fresh non-embalmed cadavers is deemed an essential part of the dissection experience as it adds much needed realism to the focus of the laboratory. Stibbs and others have noted that practice interventions with fresh cadavers are more reflective of live tissues than older embalmed cadavers may provide due to the physical nature of the tissues under study, and improve the skill sets of physicians when subjected to similar diagnostic and treatment regimens in a clinical environment at later stages of their training. Thus, the modern-day dissection laboratory is modeled after a modern surgical theater, complete with availability of imaging devices, surgical instrument trays, isotonic fluids and other items and support staff typical of an active surgery center. Unlike the student lab coats adorned by the participants in past generations, complete PPE, cadaver draping, surgical attire, whiteboard and projection screen, and appropriate demeanor is not only deemed essential for instructional purposes in the current educational environment, but for safety concerns as well. Prior to the onset of each laboratory session, proper respect was offered for the cadaver as itemized in point 8 above. Prior to the dissection instruction, students typically received training on an Anatomage® table as part of their didactic anatomy lecture course. In addition, a screen projection loop depicting anatomic planes, quadrants, and other significant surface anatomy designations is presented simultaneously, such that students will have a firm identification with the anatomic region being exposed during the dissections. Body painting with a magic marker or other form of outlining is also permitted during cadaveric dissections, and helps to further reinforce lecture and dissection content retention by the student. The students have often been introduced to the cadaver as ‘your first patient’ to add an additional layer of reverence and diagnostic relevance to the exercise and setting the stage for a search for pathophysiologic signs conducting the dissection with incorporation of an autopsy perspective.

In Figure 2 and 3, When unique or remarkable findings such as depicted here are discovered during a dissection, the participants of all tables can join in the observation, dissection and discussions pertaining to the anatomic findings, treatment plans and clinical outcomes. In Figure 2A and 2B, typical anatomy classes of the 19th and early 20th Century are depicted. In this depiction, students assemble around anatomic models and are shown key structures with their major functions described by the instructor. Such instruction often precedes cadaveric prosection or cadaveric dissection in an adjacent area of the laboratory. Beyond the presentations with anatomic models, the remaining elements of anatomy lab were often an unpopular subject for many students. The twice weekly sessions in lab often lasted for up to three semesters, for a minimum of 160 or more total hours in the lab with formalin-embalmed cadavers nearby. PPE or surgical gowns were not provided, at most a student might be assigned or wear a typical lab coat and proceed without surgical gloves. We all remember the unpleasant auras that often followed us around after leaving the lab, and which odors did not improve but likely became worse as the semester dragged on. Because dissection laboratories were often in the basement level of the buildings which helped to keep the cadavers cooler and away from public view, it also limited effective ventilation thereby posing a potential respiratory or dermal formalin injury. Windows, if present, might be left open in an attempt to improve air quality. Laminar flow ventilation in anatomy labs was not yet an option and the potential health risks of chronic formaldehyde exposure on the students were unknown.

A typical group of USAT students is depicted in Figure 3, the group are participating in a mentored cadaveric dissection, during which all participants cooperate and given the opportunity to take an active part in the dissection process, some as the dissecting surgeon, some in the first assistant role. Each dissection table is planned for up to 6 to 8 students but can accommodate a maximum of 10 to 12 students. The dissection theatre includes a standing platform in the event they need to look over the shoulders of another student for better viewing. With this approach, procedures may include demonstration of a cardiac massage, dye-enhanced visualization of the coronary arteries prior to further dissection of the heart, again with maximum student participation in the process and discussions. It was not uncommon for the students to take turns to visualize and palpate an occluded vessel, kidney lesion or gallstone with this technic, thereby demonstrating the physicians’ or surgeon’s application of the use their sense of touch as an extension of their visual and intellectual senses in examinations and surgical procedures. The unembalmed cadavers add additional realism due to the greater physical similarity to live tissues than can often be attained with embalmed specimens. Additional procedures including endoscopy or bronchoscopy may also be performed during the first phase of the dissection process when the cadaver is deemed suitable for such diagnostic investigation.

Additional lab exercises include 3-D printing of body parts, endoscopy, bronchoscopy, colonoscopy, wound closure and suturing techniques, and others, where a substantial volume of pathophysiology may be discovered during the course of a cadaveric examination and dissection. Overall, the mastery of staged anatomic instruction enables students to better appreciate and reinforce the clinical manifestations of the anatomy, physiology, and neurobiology with carryover to the clinical years and beyond. Anatomy teaching hours have become significantly compressed in recent years to yield room for additional topics in molecular biology and numerous other topics now included in medical basic sciences, many of which have a connection to basic functional anatomy. As a likely result of the innovative emphasis placed on this and other topics during medical basic sciences, student test scores on the basic sciences and clinical sciences pre-licensing examinations have trended upwards with virtually all applicants finding success in their pursuit of postgraduate residency training in the USA and other nations. Because of the above cadaveric dissection program the previously once somewhat unpopular course of the past has become one of the most popular course modules in the medical basic sciences, with many students requesting the opportunity to audit the module multiple times after their initial experience. Will they become future anatomists or surgeons? Only time may answer that question.

Conclusions

Advancements in educational technology brought about by the entry of the internet age over recent decades has enabled academic programs in many disciplines to undergo unprecedented changes in educational pedagogy, particularly in the traditional classroom format of instructional delivery. Applied and practical skills, as would be developed in laboratory settings have also become an important recipient of the pedagogical advances. Adoption of computer- and internet-generated instructional content not only is economically more efficient for the institution and the instructor, it also enables the computer savvy student to benefit from greater time management, in addition to secondary time and cost savings from unnecessary hours lost and related travel expenses to- and return from a traditional lecture setting. Indeed, the time lost during transit may exceed the actual time allocated to the lecture setting. Thus, for the off-campus or otherwise serious student, a typical traditional one-hour lecture may obligate the individual to a multiple of the actual scheduled lecture hours, since while remaining at one’s computer during that time bloc could enable the generation of multiple additional hours for individual study and research. The actual one or two hours session for a laboratory experience may be extended to 4 or more consecutive hours, thereby generating an additional cost saving improvement in the educational endeavor for all participants. An updated innovative clinically focused cadaveric anatomy program is described. This program includes traditional didactic, virtual, and specialized cadaveric dissection and has improved the delivery and content retention of anatomy education for medical and graduate students and has become one of the most sought-after modules in the revised and updated curriculum. Clearly, your grandparent’s anatomy lab has left the building and is not here anymore, and is highly unlikely to return in its earlier, historical format, Rest assured that the laboratory hasn’t gone out entirely with the discarded debris, as the fundamental importance of anatomy dissection to medical and graduate education remains. Although grandad’s lab it is not likely to return any time soon in its earlier format, the fundamentals, importance and need for mastery of the instruction in gross anatomy and dissection-based skills remains solid and committed and haven’t decreased over the intervening generations. The early process has provided the fundamental basis developed over hundreds of years, since Dr Nicholaes Tulp’s early demonstrations of human dissection as artistically recorded in the ‘Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp’ (ca 1632). Today’s anatomy dissection and modularized learning programs, including computer assisted virtual anatomy programs for human and animal anatomic study via a blended-SPOC (Small Platform Online Course) internet format now enable and facilitate anatomy instruction to be more productive, meaningful and longer lasting than ever before, while enhancing the cost effectiveness for all parties involved. In addition, the added concepts enabled by integrating aspects of clinical medicine, pathophysiology, and surgical skills earned via inclusion of practical, focused dissection, contribute to greater retention of anatomic content and applied skills, and which can be further reinforced in later instructional and clinical modules undertaken. An old adage once stated, “necessity is the mother of invention” likely still rings as true in today’s environment as it was in previous generations. Some aspects of ‘how it was back when…’ are not lost to time and are still important in current pedagogy of medical education. Increasing pressures to improve the efficiency and outcomes of laboratory exercises continue but may now be assisted with new and developing technology in the form of virtual anatomy, biophysics, fiberoptics, electrophysiologic simulation, and electronic media applications. One can simulate neurophysiologic and biophysical phenomenon with predictive accuracy at the molecular level and apply fiberoptic visualizations and 3-D printing exercises not previously adaptable to the anatomy laboratory to supplement the age-old dissecting instruments of yesterday’s lab. This may include computer assisted photography, radiographic imaging, introduction to surgical techniques and procedures, all focused on better preparing the student of today for the clinical experience and demands of tomorrow. Neurophysiologic and biochemical pathways can be modeled, and virtual dose related pharmacologic alterations predicted. In small group discussions, students can discover the uniqueness of each cadaver, relate them to live situations and examples, and engage in healthy and productive discussion with the participating faculty in attendance. The curriculum incorporates current anatomical nomenclature and appropriate operating room dress and surgical demeanor, desirable for later clinical experiences. Additional IT support, combined with introduction and access to computer assisted library resources can be incorporated in semester one and made available thereafter for later modules as needed. The anatomy laboratory of the 21st century continues to be an evolving program, and which will continue to evolve and develop as technology continues to advance; an advanced anatomy curriculum as espoused in this manuscript will continue to present an exciting and dynamic opportunity to enable tomorrow’s medical students to not only master the skills of yesteryear for today but to build on and to develop new, more refined skills for a stronger and more educationally productive tomorrow. No single approach by itself is likely to be as effective in developing the intellectual and motor skills for future clinical practice as the combined approach using new and developing multimedia and AI-linked approaches. Thus, the progressive development of an innovative clinically focused cadaveric anatomy program is described which has improved the delivery and content retention of medical and graduate students and has become one of the most sought-after modules in the updated and revised clinically oriented curriculum.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the assistance of the many faculty and staff of the Miami Anatomic Research Institute for support and assistance in developing the above program for anatomy dissection for USAT medical and graduate students, many of whom entered the program with advanced certifications and degrees, seeking career advancement in the medical professions. Special thanks for the late Dr David Karam, whose dynamic lecture and brilliant surgical dissection talents were an inspiration to many of his students and to the writing of this manuscript.

Competing Interests

Authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Applications of Artificial Intelligence (AI)

The authors confirm that no applications of artificial intelligence were utilized in the development of this manuscript.

References

- de Divitiis, E., Cappabianca, P. and de Divitiis, O. The schola medica salernitana: the forerunner of the modern university. Neurosurgery 2004;vol 55:722-745. Doi 10.1227/01.neu.0000139458.36781.31 / www.neurosurgery-online.com

- Ferraris, Z.A., BA A, Ferraris, V.A. The women of salerno: contribution to the origins of surgery from medieval Italy. 1997; The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. Volume 64(6);, Issue 6, Pages 1855-1857. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-4975(97)01079-5

- Tulp, O.L., Einstein, G.P., Sainvil, F., Wu, H., Branly, R. 2024; Historical Perspectives in the Pedagogy of Anatomy Instruction in Medical and Graduate Education: From Salerno to Montserrat. Journal of Contemporary Medical Education, Vol 14(2), pp 01-09

- Versalius, A. Studio of Titian, De Humani Corporis Fabrica, Illustrated Textbook of Anatomy, , Joannes Oporinus, Publisher, Basel , June 1543

- Hajar, R. Medicine from Galen to the present: a short history.2022; Heart Views. 22(4):307–308. doi: 10.4103/heartviews.heartviews_125_21

- Ribatti, D. William Harvey and the discovery of the circulation of the blood. 2009; Chapter in: J Angiogenes Res. ;1:3. doi: 10.1186/2040-2384-1-3 PMCID: PMC2776239 PMID: 19946411

- Harvey, W. 1628; Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus, (1628, in Latin). Frankfurt. Germany.

- van Rijn, R 1632; The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, by Rembrandt.

- Kemp, A, and Masquelet, A.C. 2005; The anatomy Lesson of Dr Tulp. J J and Surg Br 30(4):379-381.

- Grauer, A. (1995). Bodies of Evidence: Reconstructing History through Skeletal Analysis. New York, NY: Wiley-Liss

- Bergman EM, Prince KJ, Drukker J, van der Vleuten CP, Scherpbier AJ. 2008; How much anatomy is enough?. Anatomical sciences education. 1(4):184-188.

- Craig S, Tait N, Boers D, McAndrew D. 2010; Review of anatomy education in Australian and New Zealand medical schools. ANZ journal of surgery 80(4):212-216.

- Older J. 2004; Anatomy: a must for teaching the next generation. The Surgeon 2(2):79-90.

- Hodge CJ. 2013; Non–bodies of knowledge: Anatomized remains from the Holden Chapel collection, Harvard University . Journal of Social Archaeology.13(1).

- Pretterklieber, M.L. Nomina anatomica-unde venient et quo vaditis? 2024; Anat Sci Int. 5;99(4):333–347. doi: 10.1007/s12565-024-00762-w

- Whitmore, I. 2002; Terminologia Anatomica: New terminology for the new anatomist. The Anatomical Record, Volume 257(2) p. 50-53. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(19990415)257:2<50::AID-AR4>3.0.CO;2-W

- Halle, M.W., Ron Kikinis, R., and , P.E. (2024) TA2 Viewer: A web-based browser for Terminologia Anatomica and online anatomical knowledge. Clin Anat. 37(6):640–648. doi: 10.1002/ca.24162

- Habicht JK, Kiessling C, Winklemann A. 2018; Bodies for Anatomy Education in Medical Schools: An overview of the sources of cadavers worldwide. Acad Med. 93(9):1293–1300.

- Periya SN. 2017; Teaching Human Anatomy in the Medical Curriculum: A Trend Review. IJAR 5(4):445–448.

- Tulp, O.L. 1984. Observations of the introduction of the personal computer to academia at Drexel University, 1983-1984. Unpublished observations of the author.

- Hunter, A. ADAM Interactive Anatomy · The Anatomy Project. BMJ. 2000 Feb 19;320(7233):521Feb 19;320(7233):521.

- Tulp, O.L. 2024; Enhancing the pedagogy of global medical education with a blended SPOC program: The anatomy lesson of Dr Nicholaes Tulp revisited. Presented at the 4th International Conference on Vaccine Research/Global Medical Education, UK Conference Series, Madrid, Spain, February 8-9, 2024.

- Tulp OL, Sainvil F, Wu H, Feleke Y, Einstein GP, Branly R. 2021; Modernization of anatomy and graduate medical education from the past to the present. The FASEB J.35(S1).

- Tulp OL, Sainvil F, Einstein GP, Scrianka A, Branly R, Wu H, et al. 2022; Incorporation of virtual enhancement in anatomy, physiology and clinical pathology instruction in medicine and veterinary medicine basic sciences. FASEB J. 36(S1).

- Tulp OL, Ortiz–Bustillo M, Einstein GP, Sainvil F, Konyk CM, Branly RL. 2018; Innovation in functional anatomy Education: The anatomy lesson of Dr Tulp from the past to the Present. The FASEB Journal. 2018;33(e): 505.4–505.4.

- Tulp, O.L. Sainvil, F, Wu, H, Einstein G P., and Branly R. 2023; The role of pathophysiology, biomedical physics and body mechanics application to clinical medicine: applications of the Anatomy Lesson of Dr Tulp in the 21st Century. In: Advanced Concepts in Medicine and Medical Research, Vol 4, BP International Pubs, London/West Bengal. IBSN 978-81-967636-4-0 / IBSN 978-81-967636-8-8 (ebook).

- Shiffer CD, Boulet JR, Cover LJ, Pinsky WW. 2019; Advancing the quality of medical education worldwide: ECFMGs 2023 Medical School Accreditation Requirement. J Med Reg. 105(4): 8–16.

- Drake RL, McBride JM, Lackman N, Pawlina W. 2009; Medical Education in the anatomical sciences: The winds of change continue to blow. Anat Sci Educ. 2(6):253–259.

- Bowsher D. 1976; What should be taught in anatomy? Med Educ.10(2): 132–134.

- Louw G, Eizenberg N, Carmichael SW. 2009; The place of anatomy in medical education: AMEE Guide no 41. Med Teach.31(5): 373–386.

- Bickley LS, Szilagyi PG, Hoffman RM, Soriano RP.2020; In: Bate’s Guide to Physical Examination and History taking. 12th edn.Lippincott Pubs. 2020.

- Fergus, H.A. 1996; Eruption: Montserrat Versus Volcano. Publisher, Peepal Tree Press.

- Tulp, O. L., Sainvil, F., Branly, T and Einstein, G.P. 2023; Micronutrient Mineral and Nutrient Content of Volcanic Soils and Creeks from the Montserrat Soufriere Hills Volcano. Nature’s Fertilizer: Mineral Nutrient Content of Volcanic Soils. European Journal of Applied Sciences, Vol – 11(2). 143-156

- Tulp, O.L., Sainvil, F., Branly, T and Einstein, G.P. 2023; Geochemistry and mineral content of ash flow from the Montserrat Soufriere Hills volcano. Int J Adv Res. (Environmental Science). 11(01):1084-1089.

- Miami Anatomic Research Institute, 8850 NW 20th St,Doral, FL 33172, previously known as the Miami Anatomic Research Center.

- Tulp, O.L., Sainvil, F, Wu, H., Einstein, G P and Branly R. 2023; The anatomy lesson of Dr Tulp: Integrating advances in the pedagogy of gross and clinically-focused anatomy laboratory. In: Current Progress in Medicine and Medical Research Vol. 1.

- Tulp, O.L. et al. Integrating advances in the pedagogy of gross and clinically-focused anatomy: A lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp. Ch 16, In: Current Progress in Medicine and Medical Research, BP Intl Publs 2023.ISBN 978-81-19491-66-7 (PRINT) and ISBN 978-81-19491-66-4 9ebook)

- Hoyek N, Collet C, Di Rienzo F, De Almeida M, Guillot A. 2014; Effectiveness of three–dimensional digital animation in teaching human anatomy in an authentic classroom context. Anat Sci Educ. 27(6):430–437.

- Asad MR, Nasir N. 2018; Role of living and surface anatomy in current trends of medical education. Acad Radiol. 25(11):1503–1509.

- Finn GM. 2010; Twelve tips for running a successful body painting teaching session in freshman gross anatomy. MedTeaching. 32:887–890.

- Finn GM, McLachlan JC. 2010; A qualitative study on the student responses to body painting. Anat Sci Educ. 3:33–38.

- Nanjunundaiah K, Chowdapurkar S. 2012; Body painting: a tool which can be used to teach surface anatomy. J Clin Diagn Res 6(8);1405-1408.

- Collett T, Kirvell D, Nakorn A, McLachlan JC. 2009; The role of living models in the teaching of surface anatomy: some experiences from a UK medical school. Med Teach. 2;31(3): e90–e96.

- Stibbs, P., Woo, J., and Brody, T. 2023;. “Utilization of AI-based tools like ChatGPT in the training of medical students and interventional radiology residents.” ScienceOpen. DOI: 10.14293/P2199-8442.1.SOP-.PFTABJ.v1.

- Hoyek N, Collet C, Di Rienzo F, De Almeida M, Guillot A. 2014; Effectiveness of three–dimensional digital animation in teaching human anatomy in an authentic classroom context. Anat Sci Educ. 7(6):430–437.

- R43 Tulp, O.L. 2024; Enhancing the pedagogy of global medical education with a blended SPOC program: The anatomy lesson of Dr Nicholaes Tulp revisited. Presented at the 4th International Conference on Vaccine Research/Global Medical Education, UK Conference Series, Madrid, Spain, February 8-9, 2024.