Integrating Vocation, Ethics, and Social Skills in Healthcare

Professional Practice in Health: Towards an Essential Integration of Vocation, Ethics and Social Skills. A systematic review

Juan-Elicio Hernández-Xumet, PT, MSc, PhD Researcher

Movement and Health Research Group, Universidad de La Laguna & Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de Candelaria, Tenerife, Spain.

Jerónimo-Pedro Fernández-González, PT, MSc, PhD Researcher

Movement and Health Research Group, Universidad de La Laguna & Gerencia de Atención Primaria de Tenerife, Tenerife, Spain.

Josmarlin González-Pérez, PT, MSc Researcher

Movement and Health Research Group, Universidad de La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain.

Juan-Claudio García-Thompson, PT, MSc Researcher

Movement and Health Research Group, Universidad de La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain.

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 June 2025

CITATION Hernández-Xumet, J-E., Fernández-González, J-P., et al., 2025. Professional Practice in Health: Towards an Essential Integration of Vocation, Ethics and Social Skills. A systematic review. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(6). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i6.6651

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i6.6651

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Background: Contemporary healthcare practice, marked by technological advances and increasing complexity, requires care beyond mere technical competence. Vocation, professional ethics, and social skills, such as empathy and assertiveness, are fundamental pillars of comprehensive, person-centred care.

Objectives: This systematic literature review analysed the existing scientific literature on the interrelationship between vocation, ethics, and social skills (with an emphasis on empathy, assertiveness, and compassion) in healthcare professionals. The aim was to identify the most relevant findings and their implications for training and professional practice.

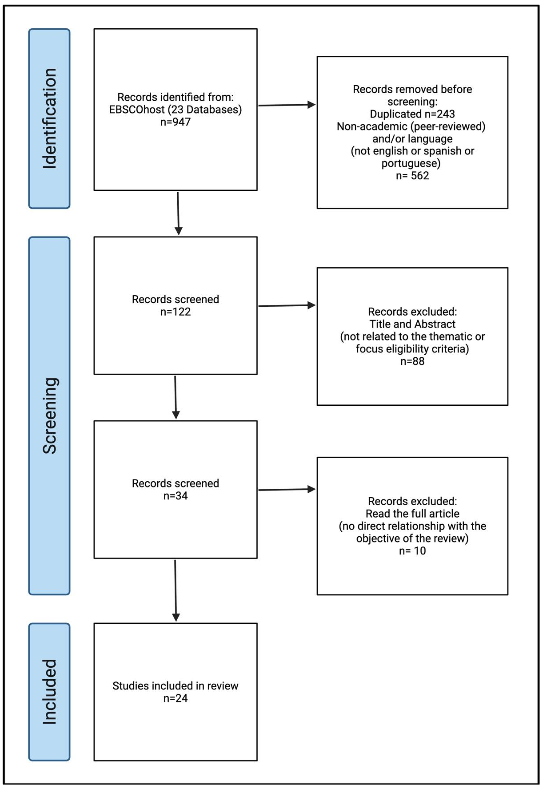

Methods: A systematic review was conducted following the PRISMA 2020 guidelines. The search was carried out in March 2025 on the EBSCOhost platform (accessing 23 databases), using key terms related to vocation/purpose, healthcare professions, and social/emotional skills. Eligibility criteria were applied to select articles published in peer-reviewed academic journals, with full text available in English, Spanish, or Portuguese. Information from the included studies was extracted and synthesised narratively and through thematic categorisation.

Results: Of 947 identified records, 24 studies met all the inclusion criteria. Qualitative analysis of these articles identified seven main thematic categories: 1) Vocation and Professional Motivation; 2) Educational Interventions and Models; 3) Ethics, Spirituality and Humanisation of Care; 4) Burnout, Self-Care and Resilience; 5) Cultural and Sociological Aspects; 6) Tensions between Technology and Human Values; and 7) Theoretical/Conceptual Studies. These findings highlight the interdependence of the constructs studied and their multifaceted impact on healthcare practice.

Conclusion: Vocation, ethics, and social skills are interconnected and essential pillars in healthcare professions, whose development and maintenance depend on a complex interaction of individual, educational, systemic, and contextual factors. Although vocation acts as a strong initial motivator, its persistence requires a deep sense of meaning, self-care strategies, resilience and a work and training environment that actively recognises and supports the well-being of professionals. Comprehensive educational approaches are needed that deliberately cultivate these dimensions, addressing the tension between technological advances and fundamental human values, to ensure ethical, competent, humanised and sustainable professional practice.

Keywords

Vocation; Professional ethics; Social skills; Health professionals; Humanisation of care; Empathy; Professional training.

1. Introduction

The contemporary healthcare landscape presents a fascinating paradox. While unprecedented technological advances and scientific discoveries offer new horizons for diagnosis and treatment, there is a growing consensus that the human element—the core of the therapeutic relationship—is more critical than ever. In an era often characterised by depersonalisation and a focus on efficiency, understanding and cultivating the fundamental human attributes of healthcare professionals is not only a desirable goal but an imperative for ensuring care that genuinely responds to people’s comprehensive needs.

1.1. The Essential Human Dimension in 21st Century Healthcare Practice

The practice of healthcare professions in the 21st century faces increasing complexity, marked by rapid scientific advances, disruptive technological transformations, and a globalised and diverse social environment. These factors drive innovation, demand new skills, and transform the way health is understood, taught, and practised globally. In this context, the effectiveness of healthcare cannot be measured solely by technical competence or process efficiency. Truly comprehensive and humane care requires the harmonious convergence of three fundamental pillars: vocation, understood as a deep personal inclination towards the well-being of the patient; professional ethics, which provides the moral and deontological framework for action; and social skills, which are essential relational tools such as empathy and assertiveness, enabling vocation and ethics to be translated into effective therapeutic interactions. This integration is not merely an embellishment or a secondary component of good practice but an intrinsic element of quality care. It responds to the fundamental need to approach the patient not only as a clinical case or a set of symptoms, but as a whole person, with their fears, hopes, values and life context.

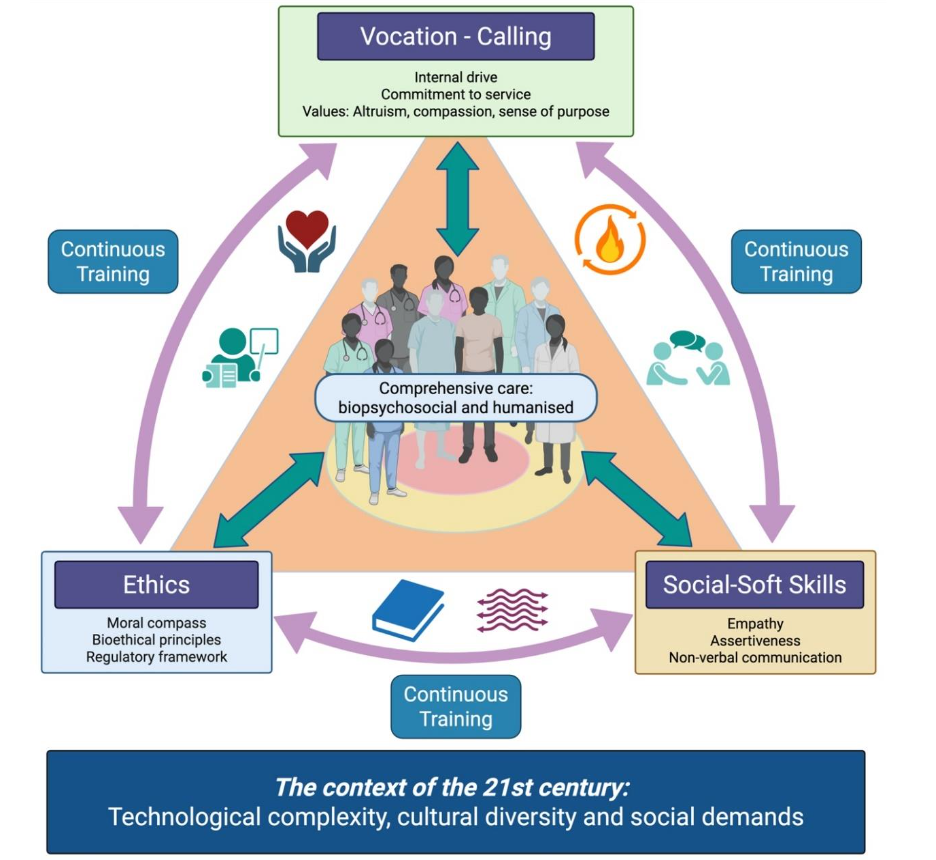

1.2. Holistic Integration: Weaving Vocation, Ethics, and Social Skills

Isolated elements cannot sustain a truly people-centred healthcare practice. A driving vocation, guiding ethics and connecting social skills must be woven together in a coherent and synergistic manner in order to establish a holistic integration that transcends fragmented or merely technical care to offer comprehensive and humanised care (see Figure 1). Vocation (the profound reason for healthcare work), ethics (what should be done and moral limits) and social skills (how to interact effectively) are not separate compartments, but interdependent dimensions that enhance each other when integrated harmoniously. Their combination generates a synergy that results in more comprehensive and meaningful care for the patient.

1.2.1. Vocation as a driving force

A genuine vocation, rooted in compassion and a desire to serve, acts as the driving force that motivates professionals not only to acquire the necessary technical skills, but also to voluntarily adhere to the ethical principles of the profession (such as beneficence or altruism) and to strive to develop communication skills (such as empathy) that enable them to better connect with the suffering and needs of the patient. Vocation gives meaning and depth to ethical commitment and efforts to improve relational skills.

1.2.2. Ethics as a Guide

The ethical framework, whether through bioethical principles or the ethics of care, provides the moral compass that guides the application of social skills and channels vocation. For example, the principle of respect for autonomy requires that communication be truthful and transparent, and that assertiveness be used to facilitate informed and shared decision-making, rather than imposing paternalistic criteria. Ethics prevents vocation from veering into reckless activism or social skills from being used in a manipulative way.

1.2.3. Social Skills as a Vehicle

Skills such as empathy and assertiveness are the tools that enable vocation and ethical principles to be translated into concrete actions that are perceived by others. Compassion (vocation/ethics) must be communicated effectively through active listening and empathetic expression so the patient feels understood and cared for. Ethical integrity (honesty, respect) is manifested in assertive and respectful communication, even when conveying difficult information. Without adequate social skills, vocation can remain a mere intention that goes unnoticed, and ethics can become a set of abstract rules with no impact on relationships.

1.3. Justification

Given the growing demand for healthcare that is not only technically competent but also deeply human, a clear understanding of how these essential attributes are fostered and sustained is essential. In this context, this literature review aims to analyse scientific output on vocation, ethics and social skills (empathy, assertiveness, compassion) in healthcare professionals to identify the most relevant findings and implications for training and professional practice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review design

This study was designed as a systematic review of the scientific literature, following the PRISMA 2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines for the search, selection, evaluation, and reporting of the articles included. The main objective is to identify, analyse and synthesise the existing academic output on the interrelationship between soft skills (emphasising empathy, assertiveness and compassion) and vocation (calling or sense of purpose) in healthcare professionals.

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

The literature search was conducted between 3 and 14 March 2025 on the EBSCOhost platform, which provides access to 23 specialised databases (MEDLINE, CINAHL, Academic Search, America: History & Life, APA PsycArticles, APA PsycInfo, Communication & Mass Media, eBook Collection, EconLit, ERIC, Fuente Académica Plus, GreenFile, Library-Information Science & Technology, MasterFILE(3), MathSciNet, MLA(2), OmniFile Full Text Mega, OpenDissertations, SPORTDiscus, Teacher Reference Center), both multidisciplinary and in the health field. The ‘Punto Q’ service, the electronic resource meta-search engine of the Universidad de La Laguna (ULL) Library, provided access to this platform. The primary search strategy, designed to be comprehensive and sensitive, was applied to the abstract field (AB) of the publications and was as follows:

AB (Vocation OR Calling OR Professional Calling OR Sense of Purpose OR Meaning in Work) AND AB (Healthcare Professions OR Health Professionals OR Medical Professionals OR Nursing OR Medicine OR Physiotherapy OR Physical Therapy OR Dentistry OR Pharmacy OR Allied Health Professions) AND AB (Social Skills OR Interpersonal Skills OR Empathy OR Compassion OR Altruism OR Assertiveness OR Communication OR Emotional Intelligence)

This search was aimed at identifying works that explored the convergence of three conceptual axes: (1) vocation and related concepts, (2) healthcare professions, and (3) relevant social and emotional skills.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria and Filters Applied

The following inclusion criteria were established:

- Articles published in peer-reviewed academic journals.

- Articles with full text available.

- Articles written in English, Spanish or Portuguese.

- Studies that thematically addressed the relationship between vocation/calling/sense of purpose and/or soft skills (such as empathy, assertiveness, compassion, communication) in healthcare professions.

Articles not meeting these criteria were excluded, such as editorials without original research content (unless they were relevant theoretical analyses), conference abstracts without full text, or studies not focused on healthcare professionals or students. Filters for publication type (peer-reviewed academic), full-text availability, and language (English, Spanish, and Portuguese) were applied directly in the EBSCOhost platform during the search.

2.4. Study Selection Process

The study selection process was carried out in several phases, following the PRISMA 2020 flow chart, and was conducted by two reviewers working in parallel. Discrepancies arising during the selection process were resolved by consensus between the two reviewers; in cases where no agreement was reached, a third author was consulted to make the final decision. The information collected was then analysed and summarised in narrative form to present an overview of the existing literature on the subject of study, identifying trends, knowledge gaps and possible future lines of research.

3. Results

3.1. Results of the Study Selection Process

3.1.1. Identification

The initial search strategy in the EBSCOhost databases identified 947 records. After removing 263 duplicates, 684 unique articles remained. Subsequently, after applying the platform filters (peer-reviewed academic publications, full text, specified languages), 122 articles were selected for the screening phase.

3.1.2. Screening

The 122 articles were screened by reading their titles and abstracts. At this stage, 88 articles were excluded because they did not meet the eligibility criteria regarding topic or focus.

3.1.3. Eligibility

The remaining 34 articles were retrieved for full-text reading. After a detailed evaluation, 10 articles were excluded because, after reading them in full, it was determined that they were not directly and relevantly related to the specific purpose of the review.

3.1.4. Inclusion

Finally, 24 studies met all the eligibility criteria and were included in this literature review for qualitative synthesis.

3.2. Information Extraction and Synthesis Process

Information was systematically extracted from each of the 24 articles included in the review. This process was carried out by the three reviewers, and the data were cross-checked to ensure consistency. The articles were read in their entirety and categorised according to their primary thematic focus, using the following seven predefined categories based on an initial review of the literature (Professional Vocation and Motivation; Educational Interventions and Models; Ethics, Spirituality, and Humanisation of Care; Burnout, Self-Care and Resilience; Cultural and Sociological Aspects; Tensions between technology and human values; Theoretical/Conceptual Studies). In addition, specific data from each study were extracted into a pre-designed template, recording the article Title, Study Population, Methodology Used, Variables Measured or analysed, and Authors’ Conclusions.

3.2.1. Professional Vocation and Motivation

Professional vocation emerges as a crucial factor. Hernández-Xumet et al. found a positive correlation between vocation and soft skills in nursing and physiotherapy students. Eley, Eley, and Rogers-Clark noted that, although altruistic motivations are key to starting a nursing career in Australia, disappointment and workload are the primary reasons for dropping out. The perception of medicine as a ‘vocation’ seems to be in decline; a study by Simões Morgado et al. showed that only 22% of Swiss doctors considered it as such, an idea on which Loxterkamp already invited critical reflection on the loss of this vocational sense in contemporary medicine. Interestingly, McManus et al. observed that, although leisure activities correlate with greater professional commitment (vocation) among doctors in the United Kingdom, they do not seem to have a direct influence on reducing burnout.

| Article | Population | Methodology | Measured Variables | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vocation of Human Care and Soft Skills in Nursing and Physiotherapy Students: A Cross-Sectional Study | Nursing and physiotherapy students | Quantitative (cross-sectional study) | Soft skills, vocation | Integrate soft skills into professional training |

| Reasons for entering and leaving nursing: an Australian regional study | Nurses (Australia) | Qualitative (interviews) | Initial motivations, factors leading to leaving the profession | Improve working conditions to retain professionals |

| Calling: Never seen before or heard of – A survey among Swiss physicians | Swiss physicians | Quantitative (survey) | Perception of medicine as a vocation | Reinforce narratives of vocation in medical training |

| Doctors’ work: eulogy for my vocation | Physician (author) | Reflective essay / Commentary | Medical vocation, professional practice, changes in medicine | It is necessary to re-examine and possibly revitalise the concept of vocation in medicine to preserve professional satisfaction and quality of care. |

| Vocation and avocation: leisure activities correlate with professional engagement, but not burnout, in a cross-sectional survey of UK doctors | Physicians (United Kingdom) | Cross-sectional survey (follow-up questionnaire) | Vocational commitment/professional commitment, burnout, leisure activities, personality, empathy, work experience, demographics | Leisure activities may foster professional commitment in doctors. However, burnout is more influenced by work factors and personal factors, and not directly by leisure. |

3.2.2. Educational Interventions and Models

The training of healthcare professionals increasingly seeks to integrate human and self-care dimensions. Chen et al. demonstrated that interventions such as loving-kindness meditation can reduce communication anxiety and improve trust in doctors. Patestos et al. proposed the Integrative Student Growth Model (ISGM) as a model for incorporating holism into nursing education at the individual, curricular and institutional levels. For their part, Létourneau, Goudreau and Cara identified milestones and indicators in the development of ‘humanistic care’ competence, linking it to job satisfaction, while Hur & Lee defined through a Delphi process, core elements for character education in medical students in Korea, such as service, empathy and respect.

| Article | Population | Methodology | Measured Variables | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The effects of loving-kindness meditation on doctors’ communication anxiety, trust, calling and defensive medicine practice | Physicians (China) | Quantitative (controlled trial) | Communication anxiety, confidence, defensive medicine | Implement mindfulness training for professionals |

| Incorporating holism in nursing education through the Integrative Student Growth Model (ISGM) | Nursing students | Theoretical model (ISGM) | Holism, self-care, clinical skills | Adopt systemic models to teach professional values |

| Humanistic caring, a nursing competency: modelling a metamorphosis from students to accomplished nurses | Nursing students and nurses | Interpretative phenomenology (intergroup comparisons; individual interviews) | Competence in ‘humanistic care’, stages of development, critical milestones, indicators of development | Nursing educators could emphasise that ‘humanistic care’ goes beyond nurse-patient communication and is integrated into care. Working conditions for nurses must be improved to maintain humanistic care after graduation. The use of manikins to develop this competency is challenged, and the importance of realistic examples is reaffirmed. |

| Identification and evaluation of the core elements of character education for medical students in Korea | Medical education professors, physicians, medical students, experts from nursing schools, and a head nurse (Korea) | Delphi and Focus Studies | Core elements of the character of doctors, character education in medical education | Eight core categorical elements of medical students’ character were identified. These results can be used as a reference for establishing goals and desired outcomes for character education at the undergraduate or postgraduate level in medicine. |

3.2.3. Ethics, Spirituality, and Humanisation of Care

The ethical and spiritual dimension is fundamental to humanisation. Kangasniemi and Haho analyse the historical ideas of Estrid Rodhe, recalling that nursing ethics is based on ‘human love’. In clinical practice, Dahan et al. analysed acts such as medical apologies after an error as crucial performative tools for restoring trust. Spirituality, according to Mahmoodishan et al., is perceived by Iranian nurses as a source of ‘meaning and purpose in work and life’, linked to religious attitudes and benevolence.

| Article | Population | Methodology | Measured Variables | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human love – the inner essence of nursing ethics according to Estrid Rodhe. A study using the approach of history of ideas | Historical texts (Estrid Rodhe) | Qualitative (history of ideas) | Ethics of care, human love | Revaluing the human dimension in professional ethics |

| Apology in cases of medical error disclosure: Thoughts based on a preliminary study | Physicians (France) | Qualitative (interviews) | Medical apologies, trust, emotional repair | Train in ethical communication after medical errors |

| Iranian nurses’ perception of spirituality and spiritual care: a qualitative content analysis study | Nurses (Iran) | Qualitative content analysis approach; unstructured interviews | Nurses’ perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care | Spirituality produces maintenance, harmony, and balance in nurses. Spiritual care focuses on respecting patients, friendly and empathetic interactions, sharing rituals, and strengthening the internal energy of patients and nurses. It promotes a positive outlook, peaceful interactions, and motivation. |

3.2.4. Burnout, Self-Care and Resilience

The well-being of professionals is key to the sustainability of the system. Andrews et al. observed that nurses often feel the need for internal or external ‘permission’ to practise self-care and self-compassion. Tempski et al. found that factors such as altruism and a sense of purpose acted as protectors against burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic among medical students. Along these lines, Tei et al. suggested that a greater sense of meaning at work can mitigate the risk of professional burnout. Furthermore, Brown et al. identified resilience and its factors, such as ‘finding one is calling’, as strong predictors of success in the clinical practices of occupational therapy students.

| Article | Population | Methodology | Measured Variables | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Needing permission: The experience of self-care and self-compassion in nursing: A constructivist grounded theory study | Nurses (United Kingdom) | Qualitative (grounded theory) | Self-care, self-compassion, institutional permission | Institutionalise self-care policies |

| Medical students’ perceptions and motivations during the COVID-19 pandemic | Medical students (Brazil) | Mixed (surveys and qualitative analysis) | Burnout, motivation, altruism | Foster a sense of purpose during health crises |

| Sense of meaning in work and risk of burnout among medical professionals | Physicians (Japan) | Quantitative (longitudinal study) | Meaning of work, empathy, burnout | Promoting a sense of meaning at work as a strategy to mitigate burnout in medical professionals. |

| Exploring the relationship between resilience and practice education placement success in occupational therapy students | Occupational therapy students | Quantitative (cross-sectional study) | Resilience, performance in practical education | The resilience factors identified as significant predictors of performance in practical education are notable findings. Students’ abilities to manage stress, find meaning in their profession, and engage in self-care activities may act as buffers. |

3.2.5. Cultural and Sociological Aspects

The socio-cultural context has a profound influence on healthcare practice. Mulligan and Garriga-López interpreted the activism of healthcare workers in Puerto Rico following disruptive events as a form of care ethics aimed at rebuilding the healthcare system. On the other hand, Bastias et al. observed how social representations of nursing change during training, shifting from an emphasis on ‘health’ among new entrants to one on ‘care’ among advanced students.

| Article | Population | Methodology | Measured Variables | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forging compromiso after the storm: activism as ethics of care among health care workers in Puerto Rico | Healthcare workers (Puerto Rico) | Qualitative (ethnography) | Activism, ethics of care, community resilience | Integrating community approaches into healthcare policies |

| Social representations of nurses. Differences between incoming and outgoing Nursing students | Nursing students (Argentina) | Qualitative (word free association) | Social representations of the nursing role | Transforming training to emphasise the human dimension |

3.2.6. Tensions between technology and human values

The relationship between technological advances and human values is a field of ongoing debate. Redinger highlighted the palpable tension in psychiatry between the focus on biomarkers and the importance of the therapeutic relationship. Jones had already explored this dichotomy between the scientific and the humanistic through the analysis of medical novels, specifically Bildungsromans.

| Article | Population | Methodology | Measured Variables | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enchantment in psychiatric medicine | Psychiatrists (USA) | Theoretical-conceptual | Technology vs. therapeutic relationship, disenchantment | Balancing technological advances with humanism in psychiatry |

| Images of physicians in literature: medical Bildungsromans | Literary works (medical novels) | Literary/theoretical-conceptual analysis | Representation of doctors in literature, medical Bildungsroman, professional development, science vs. humanism | Literature offers a way to reflect on the values, challenges, and process of medical identity formation, including the balance between technique and humanity. |

3.2.7. Theoretical/Conceptual Studies

Various conceptual studies address the pillars of the profession. Bryan-Brown and Dracup defined professionalism as a construct that requires altruism and self-regulation. Betzler questioned the idealisation of medical empathy, proposing a more precise and broader definition that recognises its limits. Vearrier developed the ‘ESIA’ (Enlightened Self-interest in Altruism) ethical model, seeking to integrate self-care with altruism to prevent burnout. Finally, Bradshaw posited that confusion about the role of nursing could stem from the abandonment of its moral tradition, proposing its necessary revitalisation.

| Article | Population | Methodology | Measured Variables | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Professionalism | Medicine | Theoretical | Altruism, self-regulation, professional ethics | Professionalism requires a balance between rights and duties. Reforming codes of ethics for modern contexts. |

| How to clarify the aims of empathy in medicine | Medicine (conceptual and practical field) | Conceptual/philosophical analysis (theoretical essay) | Medical empathy, objectives of clinical care, components of empathy | Physicians’ ignorance of the risks of empathy. The aims of empathy must be clarified to improve medical education and clinical practice. |

| Enlightened Self-interest in Altruism (ESIA) | Medical students | Theoretical model | Altruism, self-interest, sustainability | Altruism and self-interest are complementary in preventing burnout. Adopt ethical models that integrate self-care and patient care. |

| Charting some challenges in the art and science of nursing | Nursing (discipline and profession) | Theoretical-conceptual / Commentary | The art and science of nursing, the role of nursing, the moral tradition of care | Practical suggestions are needed on how this moral tradition could be reappropriated and revitalised for modern nursing, highlighting its relevance to patient well-being. |

4. Discussion

4.1. Professional Vocation and Motivation

Vocation, understood as an inner calling or a strong inclination towards a particular profession, and professional motivation, which encompasses the factors that drive and sustain the practice of that profession, are crucial elements in the health field. The studies analysed offer diverse perspectives that enrich our understanding of these constructs. A fundamental starting point is the prevalence and nature of vocation among health professionals. The study by Simões Morgado et al., conducted with Swiss physicians, investigates the concept of ‘calling,’ suggesting that the choice of medicine transcends a mere professional choice, approaching a decision with a strong component of purpose and service. This finding resonates with the idea that medicine, rather than a job, can be experienced as a fundamental dedication. Delving deeper into this line of thinking, it could be argued that the presence of this ‘calling’ could be a protective factor against depersonalisation or a driving force for the pursuit of excellence, although the study by Simões Morgado et al. focuses on its prevalence and characterisation rather than its direct effects on long-term practice.

This notion of vocation is a significant driving force from the formative stages. The research by Hernández-Xumet et al. with nursing and physiotherapy students highlights the importance of vocation and its relationship with soft skills. Although the study focuses on the correlation between vocation and soft skills, it implicitly tells us that vocation is a factor that is already present and measurable in students. We could discuss how an early vocation, such as that identified by Hernández-Xumet et al., not only guides career choice but could also predispose individuals to the development of interpersonal skills essential for care, such as empathy or effective communication, going beyond the mere acquisition of technical knowledge. The intrinsic motivation derived from a strong vocation could fuel the extra effort required to develop these soft skills.

The reasons that drive individuals to enter healthcare professions, such as nursing, are often related to this vocation. The study by Eley et al. on Australian nurses identifies altruistic reasons, the desire to help and an interest in care as key factors for entering the profession. These intrinsic motives, which align closely with the concept of vocation, are fundamental to understanding the initial career choice. However, Eley et al. also explore the reasons for leaving the profession, leading us to consider that initial vocation, although powerful, can be tested by the realities of the work environment. A possible line of work could study how the dissonance between vocational expectations (helping, caring) and the realities of the system (overwork, lack of resources) can impact long-term motivation, an aspect that Eley et al.’s results help contextualise.

The experience and meaning of vocation can change throughout a professional career, and not always in a positive way. Loxterkamp offers a more personal and critical perspective in his ‘praise’ of the medical vocation. His reflection can be interpreted as a sign of how the pressures of the modern healthcare system, bureaucratisation and loss of autonomy can erode the original sense of vocation. Loxterkamp invites us to reflect on whether vocation is a static entity or whether, on the contrary, it needs to be nurtured and protected within a work environment that recognises and values it. His article goes beyond quantitative data and offers a profound qualitative insight into the existential challenges that a professional with a strong initial vocation may face when it clashes with the pragmatism of everyday life.

Finally, the relationship between vocation, professional commitment and well-being is complex. McManus et al., in their study of physicians in the United Kingdom, found that vocation correlates with professional commitment (‘engagement’), but not with a lower incidence of ‘burnout’. This is a significant finding, as it suggests that vocation may drive professionals to be more involved and dedicated to their work, but does not necessarily protect them from burnout. It could be argued that a strong vocation could even lead some professionals to push themselves beyond their limits, increasing the risk of burnout if not accompanied by self-care strategies and a supportive work environment. The distinction made by McManus et al. between commitment and burnout about vocation is vital: one can be highly motivated and committed for vocational reasons and still succumb to burnout if conditions are not right or if vocation becomes an excessive demand without the counterbalance of personal well-being, where leisure activities or ‘avocations’ could play a role, as their study also explores.

Vocation emerges as a key motivational factor in the choice and practice of healthcare professions. It drives commitment and is associated with developing essential skills. However, vocation is not a guarantee of perpetual satisfaction or an infallible shield against professional burnout, and the reasons for remaining in the profession must consider the interaction between this internal calling and the external conditions of professional practice. Understanding this dynamic is essential for designing professional support and development strategies that attract individuals with a vocation and sustain them throughout their careers.

4.2. Educational Interventions and Models

Training competent, ethical health professionals with a strong vocation requires educational approaches that transcend the mere transmission of technical knowledge. It is essential to consider pedagogical models and specific interventions that promote the comprehensive development of students and their professional future. The studies analysed in this section offer valuable perspectives on cultivating these essential qualities.

A fundamental approach is adopting holistic educational models that recognise the multidimensional nature of students. The work of Patestos et al. is a clear example of this trend, proposing the ‘Integrative Student Growth Model (ISGM)’ for nursing education. This model emphasises the need to incorporate holism, seeking integrated student growth encompassing the cognitive, personal, and professional. By going beyond a purely technical curriculum, the ISGM aims to train nurses who are competent in their skills and well-rounded and resilient professionals, better prepared for the complexities of care. This suggests that developing soft skills and a deeper understanding of one’s vocation can be direct outcomes of an educational approach that values and nurtures the whole student.

In this same vein of holistic development, character education is crucial, especially in medical training. Hur & Lee address this need by identifying and evaluating the core elements of character education for medical students in Korea. Their research emphasises that virtues such as integrity, compassion, respect and responsibility are not merely desirable attributes, but fundamental elements that can and should be taught, worked on and evaluated. By defining these core elements, they provide a roadmap for healthcare institutions to implement more structured and effective character education programmes, thereby contributing to the training of ethically sound and humanely conscious professionals. This approach goes beyond the implicit learning of values, proposing an explicit and reflective inclusion of ethics and character development in the curriculum.

Beyond general models and character education, developing specific competencies such as humanistic care is essential. Létourneau et al. describe humanistic care as a key competency and model its development as a ‘metamorphosis’ that transforms students into accomplished nurses. This concept of metamorphosis highlights that humanistic care is not innate to everyone, nor is it acquired passively, but rather is the result of an evolutionary process influenced by education, reflection, and role modelling. The study suggests that educational institutions can facilitate this transformation by creating learning environments that foster empathy, therapeutic presence, and a deep understanding of the patient experience. This implies that pedagogical strategies should include opportunities for reflective practice and interaction with positive models of humanistic care.

Finally, specific interventions that can directly impact the well-being of professionals and their interpersonal skills and vocational experience are explored. The recent study by Chen et al. on the effects of loving-kindness meditation (LKM) on doctors is particularly revealing. Their findings indicate that this practice can reduce anxiety in communication, increase confidence, strengthen the sense of ‘calling’ or vocation and, notably, decrease the practice of defensive medicine. This intervention addresses the internal well-being of physicians (reducing anxiety, strengthening vocation) and directly impacts the quality of care and professional ethics (improving communication and trust, reducing defensive practices). The possibility that an intervention such as LKM can cultivate positive aspects while mitigating negative behaviours offers a promising avenue for complementing educational models and skills development programmes.

These studies illustrate a movement toward more intentional and multifaceted educational approaches in the health professions. From holistic models and explicit character training to the promotion of humanistic care as an evolving competency and the implementation of specific interventions for well-being and practice improvement. There is a recognition that ethical, vocational, and soft skills can and should be actively cultivated. The implication is clear: educational institutions have a crucial role and the tools to train professionals who are not only technically proficient but also compassionate, ethical, and deeply connected to the purpose of their profession. Integrating these diverse strategies could be the key to preparing the next generation of healthcare professionals for future challenges.

4.3. Ethics, Spirituality and Humanisation of Care

Ethics, spirituality and humanisation of care are intrinsically connected dimensions that form the cornerstone of healthcare and genuinely focus on the whole person. The articles selected for this section shed light on different facets of these concepts, from their philosophical foundations to their practical manifestations and the challenges inherent in their application in complex contexts.

In the search for the essence of ethics in nursing, the study by Kangasniemi & Haho, using a history of ideas approach, refers us to the thinking of Estrid Rodhe, who postulated ‘human love’ as the inner core of nursing ethics. This perspective suggests that, beyond codes and deontological principles, the basis of ethical and humanised practice lies in a deep capacity for compassionate connection and a genuine interest in the well-being of others. This ‘human love’ should not be understood as superficial sentimentality, but as a fundamental motivating force that guides ethical action and personalises care, making humanisation a natural consequence of this internal disposition.

The spiritual dimension, often intertwined with ethics and the search for meaning, is crucial to holistic care. The qualitative study by Mahmoodishan et al. on the perception of spirituality and spiritual care among Iranian nurses reveals how these professionals understand and attempt to integrate this dimension into their daily practice. Their findings underscore that, for many nurses, spiritual care is an integral part of care, recognising the transcendent needs of patients. This implies that the humanisation of care also involves validating and attending to the spiritual sphere of the patient. However, how this is understood and addressed may have important cultural nuances.

The humanisation of care and professional ethics are particularly tested in adverse situations, such as medical errors. The work of Dahan et al. on apologising in cases of medical error delves into the importance of this act for the therapeutic relationship and ethical integrity. When offered sincerely and appropriately after an error, an apology is not only an acknowledgement of fallibility, but also a deeply humanising act that can help restore trust, validate the patient’s suffering and foster a culture of transparency and learning. Their discussion goes beyond mere procedure, touching on the ethical foundations of responsibility and respect for the patient.

These studies agree that ethics, spirituality and humanisation are not optional extras, but the very fabric of quality care. From ‘human love’ as a fundamental ethical driver, through the recognition and integration of the spiritual dimension into general practice, to the manifestation of ethics and humanisation in critical moments such as error management, the need for active and ongoing commitment is emerging. Fostering these dimensions requires not only the individual willingness of professionals, but also health systems and educational programmes that value, teach and actively promote them.

4.4. Burnout, Self-Care and Resilience

Healthcare professions and training in this field involve significant exposure to stressors that can culminate in burnout syndrome, a state of physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion. In this context, self-care and resilience emerge not as luxuries but as imperative needs for the sustainability of well-being and professional effectiveness. The studies analysed offer valuable insights into the interrelationship between these phenomena.

A key protective factor against burnout is the ability to find deep meaning in work. Research by Tei et al. with medical professionals found a negative correlation between ‘sense of meaning at work’ and the risk of burnout. This finding is crucial, as it suggests that beyond work demands, the perception that one’s work has a transcendent purpose and is aligned with personal values can act as a buffer against burnout. This connects directly to professional vocation, where a strong internal calling can infuse daily work with meaning that helps cope with the profession’s difficulties. Thus, fostering and reconnecting with this sense of purpose could be a preventive strategy against burnout.

Despite the recognised value of self-care, its practical implementation faces significant barriers, often systemic rather than individual. The study by Andrews et al., using a constructivist grounded theory approach with nurses, revealed a crucial concept: the ‘need for permission’ to practise self-care and self-compassion. This finding is significant because it shifts the narrative of self-care from a purely individual responsibility to recognising the impact of organisational culture and perceived expectations. Suppose professionals feel they require external validation to attend to their own needs. In that case, this indicates a work environment that may not inherently prioritise the well-being of its professionals, which can, paradoxically, exacerbate the risk of burnout by making it challenging to adopt protective strategies.

Resilience, understood as the ability to adapt positively to adversity, is another fundamental individual quality in health. Brown et al. explored the relationship between resilience and success in the clinical practices of occupational therapy students. Their results suggest that resilience is linked to successful performance in demanding practical settings. This indicates that resilience is not just a theoretical construct, but a functional capacity that enables students to cope with stress, learn from challenges and persevere, which could have implications for their long-term well-being and transition to professional life. Fostering resilience from the formative stages is an investment in the future health of the profession.

The interaction between these factors was intensely tested during acute crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The study by Tempski et al. on the perceptions and motivations of medical students during this period offers a window into how such events can profoundly impact well-being, vocation and resilience. Their findings are likely to show an increase in stress and risk of burnout. However, they may also reveal coping mechanisms, unexpected sources of resilience, or a reaffirmation of vocation in some students. The pandemic, therefore, serves as an extreme case that underscores the need for robust support systems and strategies to promote self-care and resilience, especially when demands far exceed usual resources.

These studies paint a complex picture where burnout is a constant threat, modulated by individual and systemic factors. While a strong sense of meaning in work and personal resilience act as protective elements, the ability to engage in self-care is often limited by organisational cultures that do not grant the necessary ‘permission’ to do so. Crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic only exacerbate these dynamics, highlighting the urgency of a comprehensive approach. Therefore, burnout prevention and well-being promotion in healthcare professions require a two-pronged approach: on the one hand, equipping individuals with tools for self-care, self-compassion and resilience building; and on the other, and crucially, transforming educational and work environments to make them genuinely supportive, safe and actively promoting well-being, recognising that the responsibility cannot lie solely with the individual to ‘be more resilient’ in the face of inherently challenging systems.

4.5. Cultural and Sociological Aspects

Health professions do not exist or operate in a social vacuum. However, they are deeply imbued with cultural meanings and subject to sociological dynamics that shape both public perception and the identity and commitment of the professionals themselves. The articles selected for this section discuss how social representations and specific socio-political contexts influence the practice and ethics of care.

A fundamental aspect is how society perceives health professionals and how this perception can evolve. The study by Bastias et al. addresses precisely the ‘social representations’ of nurses, comparing the views of students entering the profession with those of students about to graduate. This approach allows us to understand the stereotypes and prevailing ideas about nursing in a given social context and to analyse the possible impact of university education on the transformation of these representations. The findings of this study are relevant because social representations not only shape the public’s expectations of the profession, but can also influence the self-esteem, professional identity and motivations of students and nurses themselves. The differences between entrants and graduates could indicate the extent to which formal education succeeds in challenging stereotypes and building a more autonomous and valued professional image, or whether, on the contrary, certain prejudices persist throughout training.

Beyond general perceptions, specific cultural and socio-political contexts can radically redefine the professional role and ethical commitment. The ethnographic work of Mulligan & Garriga-López in Puerto Rico after the devastating passage of Hurricane Maria offers an eloquent example of this dynamic. The authors analyse how the activism of health workers in response to the crisis and systemic neglect became a way of ‘forging commitment’ and was articulated as a manifestation of the ‘ethics of care’. This study powerfully illustrates how, in the face of extreme adversity and structural failure, the ethical responsibility of healthcare professionals can transcend the individual clinical sphere to encompass collective action, rights advocacy, and community solidarity. The commitment forged in this struggle is not only a reaffirmation of vocation but a politicisation of the ethics of care, deeply rooted in Puerto Rican history and culture of resistance. It shows how professional identity is negotiated and strengthened at the intersection of clinical practice and social responsibility.

These two studies underscore the importance of adopting a cultural and sociological perspective to understand the health professions fully. While Bastias et al. invite us to consider how circulating social representations shape professional image and identity from the beginning of training, Mulligan & Garriga-López demonstrate how contexts of crisis and struggle can profoundly reconfigure the meaning of ethical commitment, bringing it into the realm of social and collective action. Although different in approach and context, both studies agree that vocation, ethics and professional identity are not purely individual or abstract constructs, but are inevitably mediated by culture, social structure and historical vicissitudes. This suggests that training and ethical reflection in health should actively incorporate the analysis of these contextual dimensions to prepare professionals who are aware of their social role and capable of responding ethically to the complex realities in which they will work.

4.6. Technology-Human Values Tensions

The rapid advancement of technology in medicine has transformed diagnostics, treatments, and health management, offering previously unimaginable possibilities. However, this progress is not without tensions, particularly regarding the preservation of humanistic values that have traditionally been considered the heart of clinical practice. This section explores some of these tensions, reflecting on balancing technical sophistication and the human essence of care.

The tension between biomedical and technological approaches (psychopharmacology, neuroimaging) and a deep understanding of the subjective human experience can be particularly palpable in fields such as psychiatry. Redinger introduces the provocative concept of ‘enchantment in psychiatric medicine’. While the article itself would explore the nuances of this term, its invocation suggests a critique of a possible ‘disenchantment’ of psychiatry; a risk that the focus on neurobiological mechanisms and technical solutions may overshadow the richness, mystery, and meaning inherent in the human mental experience and the therapeutic encounter. A call for ‘enchantment’ could be interpreted as an invitation to resist reductionism, to value the patient’s narrative, the therapeutic relationship as a space for deep connection, and to maintain an openness to complexity and the unquantifiable, ensuring that technology is a tool in the service of a more holistic understanding and not a substitute for it.

Historically, the humanities, particularly literature, have functioned as a critical mirror and repository of wisdom about the human dimensions of medicine. Jones analyses ‘images of doctors in literature’, focusing on the genre of the medical Bildungsroman, i.e. novels that narrate a doctor’s training and ethical and personal development. These literary narratives often bring to the fore precisely the tensions that concern us here: the struggle between necessary scientific objectivity and compassionate empathy, the (sometimes dehumanising) impact of technology on the doctor-patient relationship, the ethical dilemmas that arise in daily practice, and the evolution of the doctor’s ideals throughout their career. As Jones points out, these literary representations not only reflect social perceptions and concerns about medicine but also offer spaces for reflection on the fundamental values of the profession. They serve as a counterpoint to purely technical discourse, reminding us of the importance of character, integrity, and humanity in medicine.

Although coming from different fields (contemporary psychiatry and literary analysis), these two perspectives converge on the need to cultivate human values actively in the face of technological advancement. The risk of ‘disenchantment’ or of a medical practice that loses its ethical and human compass is real if technology is not integrated reflectively. The humanities, as Jones’s analysis of literature demonstrates, provide crucial tools for this reflection, helping to train professionals who are technically competent, ethically aware, and humanly sensitive. The implication is clear: to navigate the tensions between technology and human values, medicine needs to look both forward, embracing innovation, and inward and backward, drawing on the accumulated wisdom of the humanities and fostering an ‘enchantment’ or renewed appreciation for the irreducible complexity and value of each human being it serves. Integrating these reflections into training and ongoing practice is essential if technology is to enhance, rather than erode, the humanistic heart of medicine.

4.7. Theoretical/Conceptual Studies

A solid conceptual foundation is essential for rigorously addressing issues such as vocation, ethics, and soft skills in the health professions. Clarifying key terms, exploring their nuances, and understanding the very nature of these professions allows us to advance the discussion and practice in a more informed manner. The articles in this section contribute significantly to this conceptual task.

A central and omnipresent concept is that of ‘professionalism.’ Bryan-Brown & Dracup directly address this construct in their editorial. Although written several years ago, its relevance endures. Professionalism encompasses a set of attributes, behaviours and values that define the identity and practice of a member of a profession, such as technical competence, ethical integrity, responsibility, accountability, commitment to service and, often, a component of altruism. Establishing a clear understanding of what constitutes professionalism is essential for professional self-regulation, guiding training, and maintaining public trust, as well as providing a framework that integrates many of the other elements discussed, such as ethics and interpersonal skills.

Within the broad umbrella of professionalism, specific skills such as empathy require detailed conceptual attention. Betzler focuses on ‘clarifying the goals of empathy in medicine.’ This philosophical analysis is crucial because empathy, although universally valued, can be understood and applied differently. Betzler explores whether the primary goal is accurate cognitive understanding of the patient’s condition, affective sharing, or whether it seeks specific ends such as improving the therapeutic relationship, increasing treatment adherence, or simply offering comfort. By unpacking these possible goals, the teaching of empathy and its ethical and practical use in clinical practice can be better guided, avoiding both superficial instrumentalisation and the possible emotional exhaustion of the professional.

Another key concept, altruism, often invoked as a pillar of the healthcare vocation, is examined from an innovative perspective by Vearrier in discussing ‘Enlightened Self-interest in Altruism’ (ESIA). This conceptual framework proposes that altruism does not necessarily imply total self-sacrifice, but can coexist with and even be enhanced by ‘enlightened self-interest’, i.e. the understanding that acting for the benefit of others can also result in significant benefits for oneself (such as personal satisfaction, a sense of purpose, psychological well-being). Presented as an educational framework, ESIA challenges simplistic views of altruism and could offer a more sustainable model for ethical motivation in demanding professions, connecting the vocation of service with self-care and resilience.

Finally, reflecting on the intrinsic nature of the healthcare professions themselves is important. Bradshaw, in his article on the challenges in the ‘art and science of nursing’, addresses this fundamental duality. Although science provides the foundation of knowledge and technical skills, nursing (and many other health professions) also involves an ‘art’: the judicious and compassionate application of that knowledge, clinical intuition, communication skills, therapeutic presence, and ethical decision-making in complex situations. Bradshaw reminds us that excellent practice lies in the skilful integration of both dimensions and that challenges often arise in balancing and appropriately valuing both scientific rigour and human sensitivity.

These theoretical and conceptual studies provide an indispensable foundation for our discussion. Clearly defining professionalism, analysing key components such as empathy in depth, exploring motivational models such as ESIA for altruism, and reflecting on the dual nature of healthcare professions allows us to move beyond generalities. This conceptual clarity is not an end in itself, but an essential tool for designing more effective educational interventions, fostering more ethical work environments, and supporting professionals in cultivating a competent, compassionate, and sustainable practice.

4.8. Limitations of the Study

Although this systematic review has made it possible to integrate a wide range of perspectives on vocation, ethics, soft skills, and other crucial factors in the health professions, it is important to recognise certain limitations inherent in the studies included and in the review process itself:

- Generalisation and Contextualisation: Many studies analysed are limited to specific geographical, cultural and professional contexts (e.g., Swiss doctors, Australian nurses, Korean students, professionals in Puerto Rico after a disaster). Although the central themes are universally relevant, the direct applicability and generalisation of some findings to other healthcare and cultural settings should be approached with caution, recognising the influence of context.

- Methodological and Conceptual Heterogeneity: The review has integrated various methodological approaches, including quantitative studies, qualitative studies, reviews, theoretical reflections, and conceptual analyses. This richness allows for a multidimensional understanding but makes direct comparison and unified synthesis of results difficult. Definitions of constructs such as ‘vocation’ or ‘spirituality’ may also vary across studies, adding a layer of complexity to the integrated interpretation.

- Temporality of Some Studies: Some conceptual and empirical works have been included that, although fundamental and relevant to the discussion, were published more than a decade ago. While the issues they address (such as professionalism, the art-science duality in care, or tensions between technology and humanism) have enduring relevance, current dynamics in health systems, technology, and professional education may introduce nuances not fully reflected in these older works.

- Variable Depth by Subject Area: The robustness and depth of the analysis in each thematic block of the discussion depend intrinsically on the number and focus of the articles selected and available for this review in those areas. For example, the discussion on ‘Technology-Human Values Tensions’ was based on a more limited number of sources, with a strong conceptual component.

- Potential Publication Bias: As with most literature reviews, possible publication bias cannot be completely ruled out. Studies with insignificant results or findings that contradict the prevailing narratives on the importance of vocation, the effectiveness of certain educational interventions, or the nature of professionalism may be underrepresented in the published literature.

- Nature of the Synthesis: This review has conducted a narrative and interpretive synthesis of the findings of the selected studies to construct a coherent thematic discussion.

Recognising these limitations does not diminish the value of the findings and discussion presented; rather, it helps contextualise the conclusions and identify areas for future research that may address some of these gaps or nuances.

5. Conclusion

This literature review concludes that vocation, ethics and soft skills are interconnected and essential pillars in healthcare professions, whose development and maintenance depend on a complex interaction of individual, educational and contextual factors. Vocation acts as a strong initial motivator, but its persistence and ability to protect against professional burnout are limited if it is not accompanied by a deep sense of meaning in work, self-care strategies, resilience, and a work and training environment that actively recognises and supports the well-being of professionals. Likewise, ethics and the humanisation of care, which manifest themselves from personal commitment and attention to the spiritual dimension to responding to systemic dilemmas and the influence of the sociocultural context, need to be deliberately cultivated and not simply assumed as inherent traits.

Comprehensive educational approaches that transcend mere technical competence are needed, actively fostering character development, humanistic care, empathy and other soft skills, while addressing the inherent tension between technological advances and the preservation of fundamental human values. Educational and healthcare institutions play a crucial role in creating organisational cultures that not only value these humanistic and ethical dimensions, but also promote conceptual reflection, support among professionals and the conditions necessary for professional practice that is ethical, competent, humanised and sustainable in the long term, recognising the profound influence of the environment in shaping professional identity and commitment.

Conflict of Interest Statement:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Statement:

None.

Acknowledgements:

None.

References

1 El-Sayed A. Contemporary Research in Health and Life Sciences. Journal of AI-Powered Medical Innovations (International online ISSN 3078-1930). 09/06 2024;1(1):68-78. doi:10.60087/japmi.vol01.issue01.p78

2. Dragan IF, Dalessandri D, Johnson LA, Tucker A, Walmsley AD. Impact of scientific and technological advances. European Journal of Dental Education. 2018;22(S1):17-20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/eje.12342

3. Meen T-H, Matsumoto Y, Hsu K-S. Selected Papers from 2019 IEEE Eurasia Conference on Biomedical Engineering, Healthcare and Sustainability (IEEE ECBIOS 2019). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(8):2738.

4. Hays RB, Ramani S, Hassell A. Healthcare systems and the sciences of health professional education. Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2020/12/01 2020;25(5):1149-1162. doi:10.1007/s10459-020-10010-1

5. Faulkner E, Spinner DS, Ringo M, Carroll M. Are Global Health Systems Ready for Transformative Therapies? Value in Health. 2019;22(6):627-641. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2019.04.1911

6. Naidu T, Ramani S. Transforming global health professions education for sustainability. Medical Education. 2024;58(1):129-135. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.15149

7. Hernández-Xumet J-E, García-Hernández A-M, Fernández-González J-P, Marrero-González C-M. Vocation of Human Care and Soft Skills in Nursing and Physiotherapy Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nursing Reports. 2025;15(2):70.

8. Cerdio Dominguez D, Millán Zurita P, Cedillo Urbina AC, Félix Castro JM, Del Campo Turcios EC. Social intelligence, an elementary competence in the development of the doctor-patient relationship. Proceedings of Scientific Research Universidad Anáhuac Multidisciplinary Journal of Healthcare. 07/22 2021;1(1):52-61. doi:10.36105/psrua.2021v1n1.07

9. Ayala Garcia RJ, Huamaní Huamán LG. Medical vocation, beyond the duty of care: a review of literature from ethical and philosophical perspectives: Vocación médica, más allá del deber de cuidar: Revisión de la literatura desde el aspecto ético y filosófico. Revista de la Facultad de Medicina Humana. 12/06 2023;23(3):156 – 161. doi:10.25176/RFMH.v23i3.5635

10. Kulju K, Stolt M, Suhonen R, Leino-Kilpi H. Ethical competence: A concept analysis. Nursing Ethics. 2016;23(4):401-412. doi:10.1177/0969733014567025

11. Spitzer W, Ed S, and Allen K. From Organizational Awareness to Organizational Competency in Health Care Social Work: The Importance of Formulating a “Profession-in-Environment” Fit. Social Work in Health Care. 2015/03/16 2015;54(3):193-211. doi:10.1080/00981389.2014.990131

12. Hernández-Xumet J-E, García-Hernández A-M, Fernández-González J-P, Marrero-González C-M. Beyond scientific and technical training: Assessing the relevance of empathy and assertiveness in future physiotherapists: A cross-sectional study. Health Science Reports. 2023;6(10):e1600. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.1600

13. Mosalanejad L, Abdollahifar S. An investigation of the empathy with patients and association with communicational skills and compliance of professional ethics in medical students of Jahrom University of Medical Sciences: a pilot study from the south of IRAN. Future of Medical Education Journal. 2020;10(1):28-31. doi:10.22038/fmej.2020.41823.1280

14. Gutiérrez Fernández R. La humanización de (en) la Atención Primaria. Revista Clínica de Medicina de Familia. 2017;10:29-38.

15. H MRCA, J Enrique Empatía, relación médico-paciente y medicina basada en evidencias. Med interna Méx [online]. 2017;33(3):4.

16. Rodríguez Blanco S, Almeida Gómez J, Cruz Hernández J, Martinez Ávila D, Pérez Guerra JC, Valdés Miró F. Relación médico paciente y la eSalud. Revista Cubana de Investigaciones Biomédicas. 2013;32:411-420.

17. Fotaki M. Why and How Is Compassion Necessary to Provide Good Quality Healthcare? International Journal of Health Policy and Management. 2015;4(4):199-201. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2015.66

18. Tehranineshat B, Rakhshan M, Torabizadeh C, Fararouei M. Compassionate Care in Healthcare Systems: A Systematic Review. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2019/10/01/ 2019;111(5):546-554. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnma.2019.04.002

19. Nielsen CL, Lindhardt CL, Näslund-Koch L, Frandsen TF, Clemensen J, Timmermann C. What is the State of Organisational Compassion-Based Interventions Targeting to Improve Health Professionals’ Well-Being? Results of a Systematic Review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2025;81(5):2246-2276. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.16484

20. Taylor A, Bleiker J, Hodgson D. Compassionate communication: Keeping patients at the heart of practice in an advancing radiographic workforce. Radiography. 2021/10/01/ 2021;27:S43-S49. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radi.2021.07.014

21. Bray L, O’Brien MR, Kirton J, Zubairu K, Christiansen A. The role of professional education in developing compassionate practitioners: A mixed methods study exploring the perceptions of health professionals and pre-registration students. Nurse Education Today. 2014/03/01/ 2014;34(3):480-486. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2013.06.017

22. Marckmann G, Schmidt H, Sofaer N, Strech D. Putting Public Health Ethics into Practice: A Systematic Framework. Methods. Frontiers in Public Health. 2015-February-06 2015;Volume 3 – 2015. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2015.00023

23. Thomas JC, Schröder-Bäck P, Czabanowska K, et al. Creating codes of ethics for public health professionals and institutions. Journal of Public Health. 2025;doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdae308.

24. Athanasopoulos P, Tahzib F. The process of developing a framework for code of ethics. European Journal of Public Health. 2024;34(Supplement_3). doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckae144.1508

25. Alshareef MF, AF. How Preceptor Behaviour Shapes the Future of Medical Professionals. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2025;16:9. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S481620

26. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71

27. Eley RE, Diann; Rogers‑Clark, Cath. Reasons for Entering and Leaving Nursing: An Australian Regional Study Nov. 2010, . Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2010;28(1). doi:10.37464/2010.281.1688

28. Laura SM, Friedrich S, Mehdi G, Céline B. Calling: Never seen before or heard of – A survey among Swiss physicians. WORK. 2022;72(2):657-665. doi:10.3233/wor-205282

29. Loxterkamp D. Doctors’ Work: Eulogy for My Vocation. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2009;7(3):267-268. doi:10.1370/afm.986

30. McManus IC, Jonvik H, Richards P, Paice E. Vocation and avocation: leisure activities correlate with professional engagement, but not burnout, in a cross-sectional survey of UK doctors. BMC Medicine. 2011/08/30 2011;9(1):100. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-9-100

31. Chen H, Liu C, Wu K, Liu C-Y, Chiou W-K. The effects of loving-kindness meditation on doctors’ communication anxiety, trust, calling and defensive medicine practice. BioPsychoSocial Medicine. 2024/05/10 2024;18(1):11. doi:10.1186/s13030-024-00307-7

32. Patestos C, Anuforo P, Walker DJ. Incorporating holism in nursing education through the Integrative Student Growth Model (ISGM). Applied Nursing Research. 2019/10/01/ 2019;49:86-90.

33. Létourneau D, Goudreau J, Cara C. Humanistic caring, a nursing competency: modelling a metamorphosis from students to accomplished nurses. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2021;35(1):196-207. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12834

34. Hur YL, K. Identification and evaluation of the core elements of character education for medical students in Korea. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions. 2019;16(21). doi:https://doi.org/10.3352/jeehp.2019.16.21

35. Kangasniemi M, Haho A. Human love – the inner essence of nursing ethics according to Estrid Rodhe. A study using the approach of history of ideas. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2012; 26(4):803-810. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01010.x

36. Dahan S, Ducard D, Caeymaex L. Apology in cases of medical error disclosure: Thoughts based on a preliminary study. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(7): e0181854. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0181854

37. Mahmoodishan G, Alhani F, Ahmadi F, Kazemnejad A. Iranian nurses’ perception of spirituality and spiritual care: a qualitative content analysis study. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2010;3:6.

38. Andrews H, Tierney S, Seers K. Needing permission: The experience of self-care and self-compassion in nursing: A constructivist grounded theory study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2020/01/01/ 2020;101:103436. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103436

39. Tempski P, Arantes-Costa FM, Kobayasi R, et al. Medical students’ perceptions and motivations during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLOS ONE. 2021; 16(3):e0248627. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0248627

40. Tei S, Becker C, Sugihara G, et al. Sense of meaning in work and risk of burnout among medical professionals. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2015;69(2):123-124. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12217

41. Brown T, Yu M-L, Hewitt AE, Isbel ST, Bevitt T, Etherington J. Exploring the relationship between resilience and practice education placement success in occupational therapy students. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2020;67(1):49-61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12622

42. Mulligan JM, and Garriga-López A. Forging compromiso after the storm: activism as ethics of care among health care workers in Puerto Rico. Critical Public Health. 2021/03/15 2021;31(2):214-225. doi:10.1080/09581596.2020.1846683

43. Bastias F, Giménez I, Fabaro P, Ariza J, Caño-Nappa MJ. Social representations of nurses. Differences between incoming and outgoing Nursing students. Invest Educ Enferm. Feb 2020;38(1)doi:10.17533/udea.iee.v38n1e05

44. Redinger M. Enchantment in psychiatric medicine. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2020/01/01/ 2020;47: 101823. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2019.10.003

45. Jones AH. Images of physicians in literature: medical Bildungsromans. The Lancet. 1996;348(9029):734-736. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07315-1

46. Bryan-Brown CW, Dracup K. Professionalism. American Journal of Critical Care. 2003;12(5):394-396. doi:10.4037/ajcc2003.12.5.394

47. Betzler RJ. How to clarify the aims of empathy in medicine. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy. 2018/12/01 2018;21(4):569-582. doi:10.1007/s11019-018-9833-2

48. Vearrier L. Enlightened Self-interest in Altruism (ESIA). HEC Forum. 2020/06/01 2020; 32(2):147-161. doi:10.1007/s10730-020-09406-8

49. Bradshaw A. Charting some challenges in the art and science of nursing. The Lancet. 1998; 351(9100):438-440. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)09044-2