Mentorship in Rural Medicine: Supporting Doctor Well-Being

Mentorship and rural medicine practice: Supporting the mental health of rural medical students and junior doctors

Anna Kokavec PhD1,

- College of Medicine and Dentistry, James Cook University, Townsville, Australia, 4811.

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 May 2025

CITATION: Kokavec, A., 2025. Mentorship and rural medicine practice: Supporting the mental health of rural medical students and junior doctors. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(5). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i5.6548

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i5.6548

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

The transition from medical student to first-year doctor is widely acknowledged as one of the most challenging periods in a medical career. High rates of transition failure, mental ill health, and suicide are often reported among early-career doctors, with those working in rural medicine potentially at even higher risk due to additional challenges such as professional isolation, limited resources, and demanding workloads. Mentorship has emerged as a critical form of support for medical students and doctors. However, rural healthcare organizations often struggle to find qualified mentors due to time constraints, limited institutional resources, and the high operational costs associated with formal programs. Research has shown that mentorship can take multiple forms, each with its own advantages and challenges. While traditional one-on-one peer mentorship may be the preferred option, exploring non-traditional types of mentorships (e.g., self-mentoring, online mentorship, and non-faculty individual or group support) and identifying the best fit may offer a more convenient and cost-effective way to support rural doctors. Overall, mentorship is important for the mental health of doctors, and rural healthcare organizations can foster a more competent, resilient, and mentally healthy workforce by encouraging rural doctors to engage in mentorship programs.

Keywords: Mentorship, rural medicine, mental health, well-being, resilience, self-care, peer support

Introduction

Medicine presents unique challenges that demand not only technical competence but also emotional resilience and adaptability. Rates of mental ill health and burnout among medical professionals remain high. Emerging evidence suggests that rural doctors may be at even greater risk of psychological injury due to challenges such as professional isolation, limited resources, broad clinical responsibilities, and minimal influence over rural healthcare policy.

Mentorship has emerged as a critical form of support in the medical profession, enabling students and doctors at all career stages to better navigate situational and professional challenges. Numerous studies have confirmed that mentorship not only fosters professional development but also delivers important mental health benefits, including emotional support, stress reduction, and resilience building.

Mentors play a vital role in supporting medical students, interns, and early-career doctors by guiding them through the complexities of clinical work, research, academic progression, and personal development. The positive outcomes of mentoring relationships—for both mentees and mentors, as well as the broader workplace—include enhanced sense of belonging, career optimism, perceived competence, professional growth, psychological security, and readiness for leadership roles. These benefits may counteract many of the challenges commonly experienced by doctors in rural settings.

Unfortunately, in resource-limited environments such as rural healthcare settings, sustaining traditional one-on-one mentoring relationships can be particularly impractical, leaving many students and doctors without the guidance they need. This mentorship gap is exacerbated by increasing demands for support in increasingly diverse and geographically dispersed healthcare systems.

This paper aims to review the current literature on the role of mentorship in promoting the mental health of medical students and junior doctors in rural medical settings. The following sections will provide an overview of the theoretical foundations of mentorship, explore various mentorship models and types, and examine how non-traditional mentorship programs can support students and early-career doctors in navigating the unique challenges of rural medicine.

Rural versus urban medicine

People living in rural environments often face limited access to healthcare resources, including fewer hospitals, diagnostic tools, and specialist services. Geographic barriers such as long distances and inadequate infrastructure can delay care and complicate emergency responses, frequently resulting in poorer patient outcomes. These limitations place significant stress on rural doctors, who are often required to work extended hours and assume responsibilities that, in urban settings, would typically be distributed among a broader healthcare team.

A recent Australian survey found that 52% of rural doctors reported working in multiple roles to meet the diverse needs of their communities. Furthermore, professional isolation is common, with approximately 32% of doctors reporting that they are the sole medical practitioner in their town. Consequently, rural doctors are more likely to experience pressure from professional responsibilities that encroach upon self-care behaviours, such as taking leave or seeking medical attention when needed. While practicing in close-knit communities allows rural doctors to develop meaningful relationships with patients and their families—often cited as a rewarding aspect of rural medicine—a major concern is the reluctance among many to seek support, even when experiencing clear signs of distress. This is often attributed to the difficulty of accessing anonymous mental health services in remote areas.

In contrast, urban medicine is characterized by high patient volumes and a faster-paced environment, which can strain healthcare systems and contribute to burnout. Urban doctors frequently manage complex cases involving comorbidities, trauma, and mental health disorders. Although urban areas are typically better equipped with advanced medical technologies and specialist services, care can become fragmented, leading to challenges in coordination. Bureaucratic demands, time pressures, and reduced clinical autonomy further contribute to emotional exhaustion among healthcare professionals. Additionally, urban practitioners often serve highly diverse populations, which can present language and cultural barriers, along with pronounced socioeconomic health disparities.

| Aspect | Rural Medicine | Urban Medicine |

|---|---|---|

| Access to care | Limited; fewer facilities and services | Readily available but often overwhelmed |

| Workload | Broad scope; one provider wears many hats | High patient volume and fast pace |

| Resources | Scarce; minimal equipment and specialists | Advanced tools and specialists available |

| Collaboration | Limited peers; professional isolation | Many providers, but care may be fragmented |

| Community Relations | Close ties; blurred boundaries | Anonymity; more culturally diverse |

| Burnout Factors | Isolation, workload, fewer breaks | Bureaucracy, emotional fatigue, depersonalization |

What is mentorship?

Mentorship is commonly defined as a relationship between a more experienced individual (the mentor) and a less experienced individual (the mentee), with the aim of fostering the latter’s professional and personal development. The objectives of mentorship include facilitating professional growth, supporting integration into the workplace, enhancing employee engagement and job satisfaction, expanding professional networks, and promoting succession planning for both individuals involved.

For mentorship to be effective, it needs to be a collaborative process in which both parties share responsibility for fostering growth and development. Clearly defining the roles and responsibilities of both mentor and mentee is essential for the success of any mentoring relationship, whether formal or informal. Rather than offering direct solutions, mentors create a safe and trusting environment that enables mentees to explore their challenges and manage both personal and professional demands. This supportive relationship typically involves processes such as problem identification, goal setting, planning, active learning, and self-reflection.

The success of mentoring relationships often depends on interpersonal compatibility and, to some extent, chance. Progress is typically measured by the achievement of evolving, and sometimes loosely defined, personal or professional goals. Unlike coaching—which focuses on skill development and performance enhancement—mentorship emphasizes holistic personal development and the cultivation of strategies for navigating complex environments. While technical skill acquisition can be a secondary outcome, it is not the primary goal of mentorship. Instead, mentorship aims to build supportive relationships that help mentees manage the unique challenges of their developmental journey. Mentors can offer mentees practical strategies such as improved time management, increased workplace engagement (e.g., seeking clinical input, participating in social interactions), clearer prioritization, re-evaluation of career and personal goals, and enhanced self-care practices.

Importantly, mentorship benefits not only mentees but also mentors and institutions. For mentors, sharing expertise and guiding motivated mentees can reinvigorate a sense of purpose and help reduce feelings of burnout. At the institutional level, structured mentorship programs have been associated with higher job satisfaction, improved development and retention of skilled professionals, reinforcement of organizational values and culture, and enhanced academic competitiveness.

Relationship between mentorship and mental health

The relationship between mentorship and mental health in medicine is both protective and developmental. Effective mentorship can serve as a buffer against the psychological challenges commonly faced by medical students, interns, and early-career professionals. According to Fishman, engaging in a supportive mentorship relationship can:

- Reduce stress and burnout: Mentors can provide emotional support, normalize struggles, and help mentees manage workload and expectations.

- Increase sense of belonging: Feeling connected to a trusted mentor can reduce feelings of isolation and imposter syndrome.

- Improve self-confidence and resilience: Encouragement and constructive feedback help mentees build confidence and cope with setbacks.

- Encourage help-seeking behaviour: Mentees may be more likely to seek mental health support when mentors model openness and advocacy for well-being.

- Increase career satisfaction and clarity: Mentorship can reduce anxiety around career uncertainty and promote purpose and direction.

On a personal level, mentors can positively impact mental health by:

- Reducing Isolation: Mentors provide a sense of connection and belonging, which is especially valuable for trainees interested in rural careers where professional isolation is common.

- Confidence Building: Positive reinforcement from mentors boosts trainees’ self-confidence as they prepare to handle the unique demands of rural medicine.

- Stress Management: Mentors share strategies for managing stress related to long hours, emotional patient encounters, and adapting to resource-limited settings.

Theoretical frameworks

Mentorship can be conceptualized through various psychological and educational theories that explain its positive impact on mental health. These frameworks provide a foundation for understanding how mentorship contributes to resilience, self-efficacy, and mental well-being. For example:

- Social Support Theory: This theory posits that social relationships provide emotional, informational, and instrumental support that can buffer individuals from the adverse effects of stress. Mentors serve as trusted advisors, role models, and confidants, helping mentees navigate complex academic and personal challenges.

- Self-Determination Theory (SDT): Developed by Deci and Ryan, SDT emphasizes the importance of autonomy, competence, and relatedness in fostering psychological well-being. Effective mentorship can help fulfill these needs by providing guidance (enhancing competence), encouraging autonomy in decision-making, and fostering a sense of connection and belonging.

- Cognitive Apprenticeship: In this educational framework, learning occurs through guided experiences with an expert. Applied to mentorship, it highlights how mentors help students gain confidence and skills through real-world engagement, which can reduce uncertainty and anxiety.

- Communities of Practice: This theory views learning as a social activity that occurs within a group of people with a shared interest. Mentorship fosters inclusion in professional communities, which is particularly crucial in rural settings where professional isolation is common.

Types of mentorships

Mentorship can come in many forms, each offering different kinds of support depending on the mentee’s goals, career stage, and personal circumstances. For example:

- Traditional One-on-One Mentorship: This focus is on providing career guidance, professional development, and emotional support. For example, a senior doctor or academic mentors a junior (e.g., medical student, resident).

- Self-mentoring: Individuals take responsibility for their own learning and growth. Self-mentoring promotes self-awareness, independent learning, and personal responsibility. Based on three core principles, self-reflection, goal setting and action planning, and resource utilization and networking.

- Peer Mentorship: Between individuals at a similar level of training or career stage (e.g., med students mentoring each other). This style of mentorship offers relatable advice, shared experiences, and mutual support.

- Near-Peer Mentorship: Involves someone slightly more advanced (e.g., a resident mentoring a med student). Helps bridge the gap between junior and senior perspectives.

- Group Mentorship: A single mentor guiding multiple mentees, or a group of mentors mentoring a group. Encourages shared learning and broader perspectives.

- Team or Mosaic Mentorship: Mentees build a “team” of mentors who each offer guidance in different areas (e.g., research, clinical practice, work-life balance). Acknowledges that no one mentor can meet all needs.

- E-Mentorship / Virtual Mentorship: Conducted primarily online or via digital platforms. Ideal for remote settings or when in-person mentoring is limited.

- Formal vs. Informal Mentorship: Formal: Structured programs with assigned mentors, goals, and timelines. Informal: Organically formed relationships based on mutual interest and trust.

- Sponsorship (a related but distinct concept): A senior figure actively advocates for the mentee, helping them secure opportunities (e.g., promotions, speaking engagements). Focused more on advancement than guidance.

- Cultural or Identity-Based Mentorship: Mentor and mentee share aspects of identity (e.g., gender, ethnicity, LGBTQ+ status). Offers a safe space to navigate challenges tied to personal identity in medicine.

Challenges for students and early career doctors

Attending medical school can be an intense and demanding experience, characterized by high academic expectations, emotional stress, and frequent exposure to human suffering. Medical students consistently report elevated levels of stress, anxiety, and burnout, which may be further exacerbated by the prospect of practicing in rural settings. A 2016 meta-analysis reported that the global prevalence of depression or depressive symptoms among medical students exceeded 24%. Furthermore, over 10% of students reported experiencing suicidal ideation, while approximately 50% showed signs of significant burnout.

Likewise, the transition from medical student to first-year doctor is widely recognized as one of the most difficult phases in a medical career. This period is frequently associated with high rates of burnout, failed transitions, and deteriorating mental health. Imposter syndrome is commonly reported among newly qualified doctors, who face a distinct array of challenges, including performance gaps, uncertainty around professional identity, unfamiliar workplace environments, and pressure to conform to cultural and institutional norms.

Benefits of mentorship

Mentoring programs are designed to support junior doctors by fostering trusted relationships in which mentees can seek guidance, share concerns, and receive encouragement from more experienced professionals. Mentors provide valuable insights into clinical decision-making, time management, and the practical realities of everyday medical practice—areas that are not always thoroughly addressed in formal training. This practical wisdom can help early-career doctors build confidence, avoid common pitfalls, and develop a strong professional identity within a supportive environment.

Importantly, mentorship also offers critical psychological support during a particularly vulnerable period. For example, mentoring relationships can normalize the emotional highs and lows inherent in medical practice, helping mentees manage stress, process challenging patient encounters, and cultivate healthy coping strategies. A mentor may serve as a stabilizing influence, providing reassurance in the face of uncertainty, self-doubt, and the emotional toll of patient care. Regular feedback, encouragement, and validation from a trusted mentor can enhance self-confidence and reinforce a sense of competence. This form of emotional support is essential in sustaining a positive self-image and building psychological resilience.

A recent systematic review investigating the benefits and drawbacks of mentorship for first-year doctors found that formalized, near-peer, and tiered mosaic mentoring models offer substantial psychosocial and professional advantages. These types of mentoring programs were shown to be particularly effective in supporting early-career doctors, as they help bridge the gap between medical school and clinical practice by addressing training deficiencies, alleviating emotional stress, and mitigating the negative effects of hierarchical structures, bullying, and emotional suppression.

Challenges of rural medicine

Working in independent practice in rural or underserved areas presents distinct challenges and can be particularly stressful. In these settings, medical students and residents must manage not only the academic and clinical demands common to all training environments but also additional stressors unique to rural practice. For instance, trainees in rural or remote locations may encounter environmental stressors such as geographic and social isolation, limited access to health and well-being services, and reduced opportunities for academic mentorship and career development. Mentorship can play a pivotal role in alleviating the psychological burden associated with rural medical education by offering the following forms of support:

- Exposure to Rural Practice: Mentors based in rural areas can provide realistic insights into the day-to-day demands of working in underserved communities. This includes navigating a wide range of clinical presentations and developing resourcefulness in the face of limited infrastructure.

- Guidance on Rural Career Pathways: Many medical students have limited awareness of the trajectories available within rural medicine. Mentors can demystify these pathways by sharing their own experiences, helping mentees understand both the rewards and the challenges, and often inspiring commitment to rural healthcare careers.

- Skill Development: Mentors assist trainees in acquiring essential skills for rural practice, such as managing complex, undifferentiated cases with minimal specialist support and utilizing telemedicine to extend care delivery.

Rural mentorship

Mentoring can be conceptualized as a longitudinal relationship grounded in shared personal and professional interests between a more experienced medical practitioner and a student. Unlike short-term clinical placements, which are often tied to specific learning outcomes within the formal curriculum, mentorship is defined by its supportive and holistic nature. It exists outside traditional academic structures and emphasizes personal growth, identity formation, and professional integration. Nevertheless, several Australian universities have recognized the value of mentorship and have formally embedded it into extended rural clinical placement programs. These initiatives allow students to rotate across hospitals, general practices, and community health services while receiving sustained guidance from dedicated mentors.

Mentoring relationships may develop informally, with students independently seeking guidance from experienced rural practitioners. However, in Australia, structured programs—such as the Rural Australia Medical Undergraduate Scholarship and the John Flynn Placement Program—offer more systematic avenues for sustained mentor-mentee engagement. These programs provide students with consistent exposure to rural clinical settings and long-term relationships with mentors who model both clinical excellence and adaptability in resource-limited contexts.

When designing effective mentorship programs—whether formal or informal—it is important to clearly outline mutual expectations. Successful mentoring involves more than the transmission of clinical knowledge; it provides a psychologically safe space for students to work through personal and professional challenges. Rather than offering direct solutions, the mentor supports reflective problem-solving through a structured process that includes identifying challenges, setting goals, planning actions, engaging in meaningful learning activities, and ongoing self-reflection. Best practices in rural mentorship program design should therefore include the following key elements:

- Longitudinal engagement between mentors and mentees to allow for trust and professional identity development.

- Flexible, student-centred models that combine structure with personalization, acknowledging the diverse goals and experiences of students.

- Training and support for mentors to ensure they are equipped to guide students effectively, particularly around sensitive issues like mental health, professional uncertainty, and career planning.

- Embedded rural immersion experiences that allow students to engage directly with the realities of rural practice under the guidance of experienced mentors.

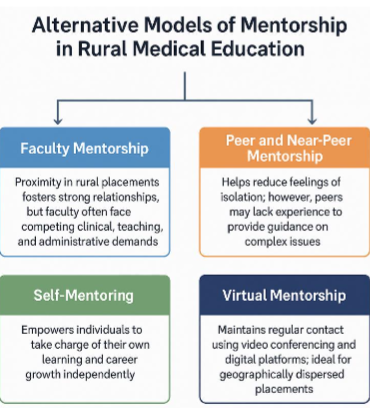

Alternative Models of Mentorship in Rural Medicine

Traditional mentoring has long supported professional development through skill-building, emotional support, and career advancement. However, many rural organizations struggle to provide enough qualified mentors due to time constraints, limited institutional resources, and the high operational costs associated with formal programs.

In rural training environments, mentorship can take multiple forms, each with its own advantages and challenges. Faculty mentorship, for instance, is often strengthened by the proximity and frequency of interactions typical of rural placements. These conditions may foster strong, personalized relationships between students and teaching staff. Nevertheless, rural faculty members are frequently overextended due to competing clinical, teaching, and administrative demands, which may limit their capacity to engage fully in mentorship roles.

Peer and Near-Peer Mentorship

Peer mentorship offers a promising solution to some of the challenges faced by rural health organizations. The shared experiences among peers can foster solidarity, reduce feelings of isolation, and normalize common difficulties. Peer relationships often encourage open discussions about mental health, reducing stigma and promoting psychological well-being. However, peers may lack the experience or authority to provide effective guidance on complex academic, clinical, or professional matters.

Near-peer mentorship—where senior students or recent graduates mentor their junior counterparts—is particularly effective in rural medical education. These mentors, having recently navigated rural placements themselves, can offer timely and relevant insights, emotional support, and practical advice. While often informal, such relationships are especially valuable in easing the transition into rural practice.

Self-Mentoring

In recent years, self-mentoring has emerged as a flexible and cost-effective alternative to traditional mentorship models. It empowers individuals to take responsibility for their own learning and professional growth without depending on the availability of a formal mentor. Self-mentoring promotes self-awareness, autonomy, and confidence, enabling healthcare professionals to adapt proactively to evolving workplace demands.

The concept of self-mentoring was initially introduced in 1986 to assist nurses in independently navigating the rapidly changing healthcare landscape. It has since been expanded to support academics and healthcare professionals more broadly, offering a structured and adaptable strategy for continuous development, particularly in environments where traditional support systems are limited or absent.

Virtual Mentorship

Given the geographic dispersion of rural placements, virtual mentorship has become increasingly important. The use of video conferencing and digital communication platforms allows for consistent and meaningful contact between mentees and mentors who may be located in urban centres or other remote regions. Although in-person mentorship remains the preferred modality for many, online mentorship has been shown to offer comparable benefits in terms of psychosocial support and career development. Moreover, virtual mentorship addresses many of the logistical barriers associated with rural training, including limited transportation, institutional support, funding, and the recruitment of local mentors.

Support provided by non-Teaching faculty

An emerging yet underexplored form of mentorship is the support provided by non-teaching faculty, such as administrative staff, wellness coordinators, and student support officers. For example, non-teaching mentors such as an academic advisor and home group facilitator, are a valuable component of a comprehensive mentorship strategy because, while not directly involved in clinical instruction, these individuals can positively impact student mental health and professional development by:

- Accessibility and Approachability: Non-teaching staff may be perceived as more approachable, especially when students hesitate to discuss personal struggles with their academic supervisors. Their non-evaluative role can foster open dialogue and trust.

- Continuity and Institutional Knowledge: Unlike clinical preceptors who may rotate through placements, non-teaching faculty often remain constant fixtures within rural campuses. This continuity can offer students stable support over extended periods.

- Specialized Support: Staff with training in counselling, wellness/self-care, or student affairs are uniquely positioned to recognize signs of mental distress and provide timely intervention or referrals to mental health services.

- Bridge to Resources: These mentors can act as liaisons between students and various institutional resources, such as academic accommodations, financial assistance, or health services, especially in resource-constrained rural settings.

- Cultural and Community Integration: In rural placements, non-teaching faculty often have strong connections with local communities and can facilitate students’ social integration, thereby reducing cultural shock and feelings of isolation.

Academic Advisor

An academic advisor in a medical program plays a vital role in guiding students through the complexities of medical education. They provide academic support by helping students navigate the curriculum, plan course schedules, and stay on track for graduation. Advisors (who may or may not be medically trained) also assist with monitoring academic performance and identifying areas for improvement. In terms of career development, they offer objective guidance in selecting a medical specialty, preparing for residency applications, and connecting with mentors and professionals in the field.

Beyond academics, academic advisors serve as a source of personal and emotional support both on-campus and during placement. They help students manage the stress and challenges of medical training and a key aspect of their role is mentorship, which involves fostering a supportive, long-term relationship that promotes both professional and personal growth. Through mentorship, advisors encourage self-reflection, build confidence, and help students develop a sense of identity within the medical profession. Academic advisors act as advocates for students, helping them navigate institutional policies and providing support in cases of academic or personal difficulty. Their multifaceted role is essential in ensuring students succeed academically, professionally, and personally throughout their medical education.

Home Group Program

The James Cook University (JCU) Home Group Program is an example of a group near-peer support program, which can be embedded into the medicine training curriculum. The HGP is delivered in a small group format (i.e., 8-10 medical students) and can assist medical students build connections, friendships, and achieve academic success. Each home group is facilitated by an academic staff member and/or senior student (at least two years senior). Moreover, participating in the HGP is a compulsory requirement of rural medicine training, especially in the first three years of the rural JCU Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery course. Formal assessment of the JCU HGP has confirmed attending home group provides rural medical students with much needed social, professional, and academic support. In 2015, the JCU HGP was formally recognized for its outstanding contribution to student learning by fostering student connectedness, academic engagement, and academic success. The JCU HGP has three values (educational, supportive, fun) and five goals:

- Facilitate transition to university life, improving likelihood of successful performance in first year subjects.

- Provide students with a small group environment to assist them to form friendships and learning cohorts that promote a sense of belonging and connectedness.

- Provide resources and opportunities to facilitate engaging, active, student-centred, and peer-facilitated learning.

- Provide students to develop critical thinking, clinical decision-making skills, group, and interpersonal skills.

- Provide opportunities for facilitators to enhance their learning and increase their sense of medical teacher identity and purpose.

Conclusion

Rural doctors may be at even greater risk of mental ill health, suicide, and burnout when compared to their urban counterparts due to the unique challenges associated with rural medical practice. The relationship between mentorship and mental health in medicine is both protective and developmental. Effective mentorship can serve as a buffer against the psychological challenges commonly faced by medical students, interns, and early-career professionals.

Traditional mentoring has long supported professional development through skill-building, emotional support, and career advancement and (for many), in-person peer mentorship remains the preferred modality. However, in resource-limited rural healthcare settings, sustaining traditional one-on-one mentoring relationships can be impractical, leaving many students and professionals without the guidance and support they need. Rural healthcare organizations often struggle to find enough qualified mentors due to time constraints, limited institutional resources, and the high operational costs associated with formal programs. It was highlighted that mentorship can take multiple forms. For example, self-mentoring, which promotes self-awareness, autonomy, and confidence, can be a cost-effective alternative to traditional mentorship modes. Similarly, online mentorship can resolve some of the logistical barriers associated with rural training, including limited transportation, institutional support, funding, and the recruitment of local mentors.

Finally, support provided by non-teaching faculty, such as administrative staff, wellness coordinators, and student support officers was explored. It was highlighted that non-teaching mentors are a valuable component of rural medicine training because, while not directly involved in clinical instruction, these individuals can positively impact student mental health and professional development in several ways.

Conflict of Interest:

None.

Funding Statement:

None.

Acknowledgements:

None.

References:

- Pohontsch NJ, Hansen H, Schäfer I, Scherer M, General practitioners’ perception of being a doctor in urban vs. rural regions in Germany – A focus group study, Family Practice, Volume 35, Issue 2, April 2018, Pages 209–215, https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmx083

- Shanafelt TD, Sloan JA, Habermann TM, The well-being of doctors, Am J. Med 2003; 114(6): 513–519.

- Kumar S. Burnout and Doctors: Prevalence, Prevention and Intervention. Healthcare (Basel). 2016 Jun 30;4(3):37. doi: 10.3390/healthcare4030037. PMID: 27417625; PMCID: PMC5041038.

- Dean W, Talbot S, Dean A. Reframing clinician distress: moral injury not burnout, Fed. Pract 2019; 36 (9): 400–402.

- Hansen N, Jensen K, MacNiven I, Pollock N, D’Hont T, Chatwood S. Exploring the impact of rural health system factors on doctor burnout: a mixed-methods study in Northern Canada. BMC Health Serv Res 2021;21: 869. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06899-y

- Lespérance S, Anaraki NR, Ashgari S, Churchill A. Systemic challenges and resiliency in rural family practice. Canadian Journal of Rural Medicine 2022 Jul-Sep; 27(3): 91-98. DOI: 10.4103/cjrm.cjrm_39_21

- Rohatinsky N, Cave J, Krauter C. Establishing a mentorship program in rural workplaces: connection, communication, and support required. Rural and Remote Health 2020; 20: 5640. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH5640

- Taherian, K, Shekarchian, M. Mentoring for doctors. Do its benefits outweigh its disadvantages? Medical Teacher 2008;30(4), e95–e99. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590801929968

- Seehusen DA, Rogers TS, Al Achkar M, Chang T. Coaching, Mentoring, and Sponsoring as Career Development Tools. Fam Med. 2021;53(3):175-180. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2021.341047.

- Fishman JA. Mentorship in academic medicine: Competitive advantage while reducing burnout? Health Sciences Review 2021;1: 100004, ISSN 2772-6320, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hsr.2021.100004.

- Jakubik L, Eliades A, Weese M. Part 1: an overview of mentoring practices and mentoring benefits. Pediatric Nursing 2016; 42(1): 37-38.

- World Health Organization. Addressing health inequities among people living in rural and remote areas. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO https://www.who.int/activities/addressing-health-inequities-among-people-living-in-rural-and-remote-areas. Accessed 23 April 2025.

- Avon F, Fuata C. The health of our rural practitioners 2023. Rural Doctors Foundation: Rural and remote medical practitioners and community needs Research Report, 2024. https://ruraldoctorsfoundation.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Rural-practitioner-health-report.pdf

- Grossman SC. Mentoring in nursing: a dynamic and collaborative process. 2nd edn. New York, NY: Springer, 2013.

- Rohatinsky N, Udod, S, Anonson J, Rennie D, Jenkins M. Rural mentorships in health care: factors influencing their development and sustainability. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing 2018; 49(7): 322-328. DOI link, PMid:29939380

- Fishman JA.Matrix mentorship in academic medicine: sustainability of competitive advantage, Biennial Review of Healthcare Management: Meso Perspectives in Advances in Healthcare Management 2009;8:155–171.

- Fraser, J. (2016). Mentoring medical students in your general practice. Australian Family Doctor, 45(5), 270-273.

- Zerzan J, Hess R, Schur E, Phillips R, Rigotti N. Making the most of mentors: A guide for mentees. Acad Med 2009;84(1):140–44.

- Weng H, Huang Y, Tsai C, Chang Y, Lin E, Lee Y. Exploring the impact of mentoring functions on job satisfaction and organizational commitment of new staff nurses. BMC Health Services Research 2010; 10: 240.

- Barrera, M., & Bonds, D.D. (2005). Mentoring relationships and social support. In Du Bois, D., & Karcher, M.J. (Eds)., Handbook of Youth Mentoring, pp. 133-142. Sage Publications. ISBN: 1452261709, 9781452261706

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation Development and Wellness. Guilford Publishing; 2017.

- Merritt C, Daniel M, Munzer BW, Nocera M, Ross JC, Santen SA. A Cognitive Apprenticeship-Based Faculty Development Intervention for Emergency Medicine Educators. West J Emerg Med. 2018 Jan;19(1):198-204. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2017.11.36429. Epub 2017 Dec 18.

- Holland E. “Mentoring communities of practice: what’s in it for the mentor?”, International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education 2018; 7(2): 110-126. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMCE-04-2017-0034

- Cruess, Richard L. MD; Cruess, Sylvia R. MD; Steinert, Yvonne PhD. Medicine as a Community of Practice: Implications for Medical Education. Academic Medicine 93(2):p 185-191, February 2018. | DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001826

- Stoller, A. Traditional and Critical Mentoring. Radical Teacher 2021;119: 52–60. https://doi.org/10.5195/rt.2021.765

- Mohd Noor NF, Zulkifli Z, Ramli RA, Fariz M. Reinventing Mentorship: From Traditional One-on-One Mentoring to Self-Mentoring. International Journal of Research and Scientific Innovation 2024;11:99-107.

- Musgrove E, Bil D, Bridson T, McDermott B. Australian healthcare workers experiences of peer support training during COVID-19: Hand-n-hand peer support. Australian Psychiatry 2022;30(6): 722-727.

- Oak S, Glickman C, McMackin K. Near-peer Mentorship: Promoting Medical Student Research With Resident Pairing. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2025 Mar 17;12:23821205251329659. doi: 10.1177/23821205251329659.

- Akinla O, Hagan P, Atiomo W. A systematic review of the literature describing the outcomes of near-peer mentoring programs for first year medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2018.

- Oliveira R. Group mentoring in practice. Journal of New Librarianship 2018; 3(2):375–378. https://doi.org/10.21173/newlibs/5/20

- Khatchikian, A.D., Chahal, B.S. & Kielar, A. Mosaic mentoring: finding the right mentor for the issue at hand. Abdom Radiol 2021;6: 5480–5484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-021-03314-2

- Wallis JAM, Riddell JK, Smith C, Silvertown J, Pepler DJ. Investigating patterns of participation and conversation content in an online mentoring program for Northern Canadian youth. Mentoring and Tutoring: Partnership in Learning 2015; 23(3): 228-247.

- Young L, Kent L, Walters L. The John Flynn Placement Program: Evidence for repeated rural exposure for medical students. Aust J Rural Health 2011;19(3):147– 53.

- National Rural Health Alliance. Rural Australia Medical Undergraduate Scholarship. Deakin, ACT: National Rural Health Alliance, 2015. Available at ramus.ruralhealth. org.au.

- Sharma, G, Narula, N, Ansari-Ramandi, M, & Mouyis, K. The Importance of Mentorship and Sponsorship: Tips for Fellows-in-Training and Early Career Cardiologists. Journal of the American College of Cardiology Case Reports, 2019 Aug, 1 (2) 232–234.

- Peifer J S, Lawrence E C, Williams J L, Leyton-Armakan J. The culture of mentoring: Ethnocultural empathy and ethnic identity in mentoring for minority girls. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 2016; 22(3): 440-6.

- Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Eacker A, Harper W, Massie Jr FS, Power DV, et al. Race, ethnicity, and medical student well-being in the United States. Archives of Internal Medicine 2007; 167: 2103–2109.

- Leahy CM, Peterson RF, Wilson IG, Newbury JW, Tonkin AL, Turnbull D. Distress levels and self-reported treatment rates for medicine, law, psychology and mechanical engineering tertiary students: Cross-sectional study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 2010;44:608–615.

- Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, Segal JB, Peluso MJ, Guille C, et al. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2016; 316: 2214–2236.

- Dyrbye L, Shanafelt T. A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents. Medical Education 2016; 50:132–149.

- Hu KS, Chibnall JT, Slavin SJ. Maladaptive perfectionism, impostorism, and cognitive distortions: Threats to the mental health of pre-clinical medical students. Academic Psychiatry 2019; 43: 381-385.

- Winderbaum J, Coventry LL. The benefits, barriers and facilitators of mentoring programs for first-year doctors: A systematic review. Med Educ. 2024;58(6): 687‐696.

- Chanchlani S, Chang D, Ong JS, Anwar A. The value of peer mentoring for the psychosocial wellbeing of junior doctors: a randomised controlled study. Med J Aust. 2018;209(9):401-405.

- Sng JH, Pei Y, Toh YP, Peh TY, Neo SH, Krishna LKR. Mentoring relationships between senior doctors and junior doctors and/or medical students: a thematic review. Med Teach. 2017;39(8):866-875.

- Ong J, Swift C, Magill N, et al. The association between mentoring and training outcomes in junior doctors in medicine: an observational study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(9):e020721.

- Sambunjak D, Straus S, Marusic A. A systematic review of qualitative research on the meaning and characteristics of mentoring in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25(1):72–78.

- Alliott R. Facilitatory mentoring in general practice. BMJ 1996;313(suppl): S2–7060.

- Eley D, Baker P, Chater B. The Rural Clinical School Tracking Project: More IS better – Confirming factors that influence early career entry into the rural medical workforce. Med Teach 2009;31(10):e454–49.

- Daly M, Perkins D, Kumar K, Roberts C, Moore M. What factors in rural and remote extended clinical placements may contribute to preparedness for practice from the perspective of students and clinician? Med Teach 2013;35(11):900–07.

- Pethrick H, Nowell L, Paolucci EO, Lorenzetti L, Jacobsen M, Clancy T, Lorenzetti DL. Peer mentoring in medical residency education: A systematic review. Can Med Educ J. 2020 Dec 7;11(6):e128-e137.

- Darling LA. What to do about toxic mentors. Nurse Educator 1986 March;11(2):29-30.

- Carr ML. The Invisible Teacher: A Self-Mentoring Sustainability Model. Center for teaching excellence, 2011.

- Aquino J F, Riss R R, Multerer SM, Mogilner LN, Turner TL. A step-by-step guide for mentors to facilitate team building and communication in virtual teams. Medical Education Online 2022; 27(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2022.2094529.

- Oshiro J, Wisener K, Nash AL, Stanley B, Jarvis-Selinger S. Recruiting the next generation of rural healthcare practitioners: the impact of an online mentoring program on career and educational goals in rural youth. Rural and Remote Health 2023; 23: 8216. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH8216.

- Garringer M, McQuillin S, McDaniel H. Examining youth mentoring services across America: findings from the 2016 National Mentoring Program Survey. Boston, MA: MENTOR: The National Mentoring Partnership, July 2017.

- Kokavec A, Harte J, Ross S. Student Support in Medical Education: What Does Evidence-based Practice Look Like? In Mental Health and Higher Education in Australia. 2022. Francis, A.P. & Carter M. Springer.