Migraine and Headache: Insights on Third Window Syndrome

AssessmeP. Ashley Wackym, MD, FACS, FAAP 1,2; Carey D. Balaban, PhD 3; Todd M. Mowery, PhD 1,2nt of the Relationship Between Migraine, Headache and Third Window Syndrome

P. Ashley Wackym, MD, FACS, FAAP 1,2; Carey D. Balaban, PhD 3; Todd M. Mowery, PhD 1,2

- Department of Head and Neck Surgery & Communication Sciences, Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, NJ, United States

- Rutgers Brain Health Institute, Piscataway, NJ, United States

- Departments of Otolaryngology, Neurobiology, Communication Sciences & Disorders, and Bioengineering, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

P. Ashley Wackym: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2904-5072

Carey D. Balaban: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3570-3844

Todd M. Mowery: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7727-6353

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 January 2025

CITATION: Wackym, PA., Balaban, CD., et al., 2025. Assessment of the Relationship Between Migraine, Headache and Third Window Syndrome. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(1). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i1.6091

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i1.6091

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

Migraine is a symptomatically heterogeneous condition, of which headache is just one manifestation. This disorder is associated with altered sensory thresholding, with hypersensitivity among migraine sufferers to different sensory inputs. Hence, we suggest that sensitivity to the gravitational receptor asymmetries seen in third window syndrome is triggering migraine symptoms via this hypersensitivity-associated mechanism. When measuring the impact of headache and migraine headache in the lives of patients with third window syndrome as well as the response to surgical intervention it is essential to incorporate a validated survey instrument into clinical practice. We have found that the six-item Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) in several different cohorts has demonstrated a highly statistically significant symptom improvement after surgical management of patients with third window syndrome. This review provides the background of the spectrum of sites of inner ear dehiscence resulting in third window syndrome, as well as other manifestations of the syndrome in the context of headache and migraine in these patients.

Keywords: Cluster headache, dizziness, headache, migraine, ocular migraine, otic capsule dehiscence, perilymph fistula, superior semicircular canal dehiscence, third window syndrome, vestibular, vestibular migraine.

1. Introduction

Third window syndrome (TWS) (also known as third mobile window syndrome [TMWS] or otic capsule dehiscence syndrome [OCDS]) is a vestibular-cochlear disorder in humans in which a third mobile window of the inner ear creates changes to the flow of sound pressure level energy through the perilymph/endolymph. Sound transmission to the inner ear is normally through the oval and round window. Acoustic pressure enters through the oval window, is transmitted through the cochlea, and exits into the middle ear cavity via the round window. The fluid in the cochlea through which sound is transmitted is functionally incompressible due to the surrounding osseous structures. Movement of the cochlear fluid is thereby dependent on the mobility of the round and oval window membranes. Inward displacement of the oval window membrane via the stapes by ossicular vibration is matched by outward round window membrane displacement. However, if a third mobile window is present, some of the acoustic pressure is shunted away from the cochlea and delivered to the vestibular receptors. Normally, sound pressure delivered by the stapes to the inner ear results in only cochlear hair cell transduction due to the round window, which dissipates cochlear vibration by impedance matching. Because the vestibular labyrinth does not normally have a membrane or release valve to dissipate the introduced sound pressure, their pressure remains constant, and the vestibular end-organs are not stimulated. However, if there is an additional fenestration, the energy typically confined to the vestibule and cochlea escapes along a path of least resistance toward the defect or “third window” and during this the vestibular end-organs can be abnormally stimulated. The nature and location of this third mobile window can occur at many different sites (or multiple sites), which will be discussed later. The primary physiological symptoms include sound-induced and pressure-induced gravitational receptor dysfunction type of vertigo, migraine headaches (and variants), inner ear conductive hearing loss, autophony while speaking, and visual problems (nystagmus, oscillopsia). At the same time, individuals experience measurable deficits in basic decision-making, short-term memory, concentration, spatial cognition, and anxiety. In this review, the role of TWS and headache and migraine will be discussed, but first a description of the clinical phenotype is essential to understand the spectrum of problems these patients experience.

1.1. CLINICAL PHENOTYPE

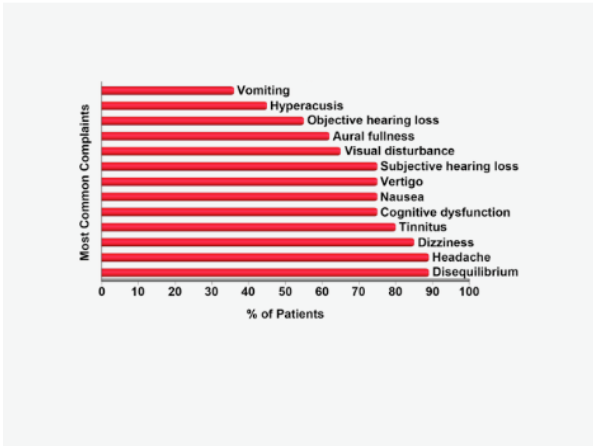

The literature has been conflicted about the frequency of symptoms and diagnostic test findings in patients with TWS. One illustrative summary that highlights the spectrum of the most common complaints from patients with perilymph fistula was published over a quarter century ago. No doubt many of these patients had TWS due to bony sites of dehiscence not yet discovered.

The three most frequent complaints were disequilibrium, headache and dizziness. Other important clinical symptoms included cognitive dysfunction, nausea, visual disturbance and objective as well as subjective hearing loss. Review of Figure 1 also demonstrates that these are extraordinarily similar to the spectrum of symptoms experienced by patients with SSCD, other TWS sites of dehiscence and vestibular migraine.

| Category | Symptom, Sign or Exacerbating Factors |

|---|---|

| Sound-induced | Dizziness or otolithic dysfunction (see vestibular dysfunction below); nausea; cognitive dysfunction; spatial disorientation; migraine/migrainous headache; pain (especially children); loss of postural control; falls |

| Autophony | Resonant voice; chewing; heel strike; pulsatile tinnitus; joints or tendons moving; eyes moving or blinking; comb or brush through hair; face being touched |

| Vestibular dysfunction | Gravitational receptor (otolithic) dysfunction type of vertigo (rocky or wavy motion, tilting, pushed, pulled, tilted, flipped, floor falling out from under); mal de débarquement illusions of movement |

| Headache | Migraine/migrainous headache; migraine variants (ocular, hemiplegic or vestibular [true rotational vertigo]); coital cephalagia; photophobia; phonophobia; aura; scotomata |

| Cognitive dysfunction | General cognitive impairment, such as mental fog, dysmetria of thought, mental fatigue; Impaired attention and concentration, poor multitasking (women > men); Executive dysfunction; Language problems including dysnomia, agramatical speech, aprosidia, verbal fluency; Memory difficulties; Academic difficulty including reading problems and missing days at school or work; Depression and anxiety |

| Spatial disorientation | Trouble judging distances; detachment/passive observer when interacting with groups of people; out of body experiences; perceiving the walls or floor moving |

| Anxiety | Sense of impending doom |

| Autonomic dysfunction | Nausea; vomiting; diarrhea; lightheadedness; blood pressure lability; change in temperature regulation; heart rate lability |

| Endolymphatic hydrops | Ear pressure/fullness not relieved by the Valsalva maneuver; barometric pressure sensitivity |

| Hearing | Inner ear conductive hearing loss (bone-conduction hyperacusis) |

Adapted from Wackym et al. and Naert et al. [Used with permission, copyright © P.A. Wackym, MD.] The more general term of TWS is more appropriate than SSCD syndrome because the same spectrum of symptoms, signs on physical examination and audiological diagnostic findings are encountered with superior semicircular canal dehiscence (SSCD), posterior semicircular canal dehiscence, posterior semicircular canal-jugular bulb dehiscence, posterior semicircular canal-endolymphatic sac/vestibular aqueduct dehiscence, lateral semicircular canal dehiscence, lateral semicircular canal-facial nerve dehiscence, cochlea-facial nerve dehiscence (CFD), cochlea-internal carotid artery dehiscence, cochlea-internal auditory canal dehiscence, cochlear otosclerosis with internal auditory canal involvement, wide vestibular aqueduct, endolymphatic sac-jugular bulb dehiscence, posttraumatic hypermobile stapes footplate, vestibule-middle ear dehiscence, modiolus (X-linked stapes gusher) and CT– TWS (see review). A common structural finding in all these conditions is an otic capsule defect that creates a ‘third window.’ In the light of our recognition that there are multiple sites where third windows occur in the otic capsule, it is interesting to note that Kohut’s definition of a PLF, from over a quarter century ago, still applies to all currently known sites producing a TWS; “A perilymph fistula may be defined as an abnormal opening between the inner ear and the external surface of the labyrinth capsule….” Hence, a fistula of the otic capsule (Kohut’s definition) can occur in any location that is in communication with perilymph, whether a SSCD, CFD, or any of the well-established sites that can result in an abnormal third mobile window resulting in a TWS.

1.2. PERIPHERAL VESTIBULAR PHYSIOLOGY AND THE NEED FOR A PRECISE LEXICON

A central problem with understanding peripheral vestibular disorders or communicating associated symptoms is the persistent, common use of poor, or at least imprecise, terminology. The terms vertigo, dizziness and disequilibrium are frequently used; however, what do they mean? To best answer this question a brief review of peripheral vestibular function is necessary. The role of the ten vestibular receptor organs is to transduce the forces associated with head acceleration and gravity into a biologic signal. Central nervous system integration of these data results in the subjective awareness of head position relative to the environment. Motor reflexes to maintain gaze and posture are generated in response to afferent vestibular input. Propulsion and orientation of the body in space depend on the vestibular system, on vision, and on the proprioceptive system. Most persons can manage with only two of these systems, but not with one. Accordingly, patients with vestibular dysfunction may have additional difficulty in maintaining equilibrium when vision or proprioception is impaired. The vestibular system, through its signal transduction by the peripheral end-organs and their afferent neurotransmission, constantly signals the position of the head in space and effects a continuous adjustment of the musculature of the body. More specifically, it signals acceleration and deceleration. The otolith organs are capable of signaling only linear acceleration or deceleration, whereas the cristae within the semicircular ducts are able to signal angular acceleration or deceleration. Constant motion (zero acceleration) cannot be detected by the vestibular system. The peripheral vestibular system represents a unique neurosensory system. At rest, the type I and type II vestibular hair cells and their primary afferent neurons maintain a relatively constant and symmetrical resting discharge rate that averages approximately 80 spikes per second. This discharge rate increases if the stereocilia are deflected toward the kinocilium of each type I or type II vestibular hair cell, and it decreases if they are deflected away from the kinocilium. Transduction of accelerated motion is brought about by movement of the endolymph, which is coupled to the stereocilia and kinocilia of the neuroepithelium. All the kinocilia are oriented in the same direction relative to the long axis of each crista, and flow of endolymph in one direction results in the same discharge characteristics for all the hair cells in each individual end-organ. A further level of redundancy exists in the push-pull organization between both sets of vestibular apparatus. For example, with rotation to the right in the horizontal plane, there is relative flow of endolymph to the left. The resting discharge rate from the right horizontal crista ampullaris is greatly increased as the cupula is deflected toward the vestibule (i.e., ampullipetal displacement), whereas the discharge rate from the left side decreases an equal amount as the cupula of the left horizontal crista ampullaris is deflected away from the vestibule (i.e., ampullifugal displacement). Normally, this bilateral system is constantly at work, receiving signals and passing them on to regulate posture and movement of the body, limbs, and eyes. Each of the five vestibular receptors on the left are paired with a specific receptor on the right. Under normal circumstances, the vestibular signals produced by each side are equal and opposite in magnitude bilaterally. The paired otolithic organs function by similar mechanisms, except that type I and type II vestibular hair cells are coupled to gravitational force through the otolithic membrane, and their overlying otoconia and the kinocilia are polarized relative to a region called the striola. Consequently, conscious perception of this normal vestibular activity does not occur. However, if there is an imbalance in the relative increase and decrease in afferent firing between paired vestibular receptors on both sides, patients experience vertigo. Vertigo is an illusion of movement in any plane or direction. Patients are deceived so that they feel themselves move or see abnormal movement of their surroundings. For rotational receptor asymmetries, patients experience a true rotational or spinning movement. For gravitational receptor asymmetries, patients have a gravitational receptor dysfunction type of vertigo. They will often describe a “rocky, wavy, tilting” perception. Other descriptors include a sensation as “being on a moving boat, the floor falling out from under them or flipping.” The terms dizziness, giddiness or disequilibrium do not accurately capture these experiences, yet they are often used, which leads to a poor understanding of TWS otic capsule defect (e.g., SSCD) symptoms by most physicians. Patients with TWS sites can experience true rotational vertigo; however, the dominant complaint is usually sound-induced gravitational-receptor dysfunction type of vertigo. This clinical observation can be blurred by vestibular migraine with true rotational vertigo being superimposed on SSCD, CFD or other TWS site of dehiscence, which will be discussed later in this review.

1.3. CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM PATHWAY ACTIVATION THAT PRODUCE SECONDARY SYMPTOMS

Most of the symptoms that disrupt the lives of patients with TWS are related to the severe symptoms that are secondary to these gravitational receptor asymmetries.

1.3.1. Autonomic Dysfunction

Autonomic dysfunction occurs to varying degrees with TWS and/or vestibular migraine; however, it is extremely common. Autonomic dysfunction also occurs with rotational receptor asymmetries. These symptoms include nausea, “cold-clammy skin,” decreased heart rate and vomiting. There have been many investigators who have studied the underlying mechanisms and pathways subserving this dysfunction.

1.3.2. Cognitive Dysfunction

Cognitive dysfunction is nearly universal in patients with TWS due to the otolithic asymmetry. This is uncommon in rotational receptor dysfunction type of vertigo as seen with benign positional vertigo, vestibular neuronitis or other disorders producing true rotational vertigo. Patients with TWS often use the following descriptors when describing their cognitive function: “fuzzy, foggy, spacey, out-of-it; memory and concentration are poor; difficulty reading – as if the words are floating on the page; trouble finding the right words; and forgetting what I wanted to say.” Surgical repair of the site of the TWS results in recovery of this cognitive dysfunction. This topic is beyond the scope of this review.

1.3.3. Altered Spatial Orientation

Patients with TWS and/or vestibular migraine often use the following descriptors in narratives about their altered spatial orientation: “trouble judging distances; feeling detached and separated or not connected, almost like watching a play when around other people; and even an out-of-body experience (in more severe gravitational receptor asymmetries).” Several groups have begun studying this phenomenon. Clinically, this spatial disorientation reverses after surgery; however, Baek and colleagues reported that spatial memory deficits following bilateral vestibular loss may be permanent. There is also evidence that normal simulation of the vestibular end organs and subsequent input to the central vestibular system is necessary to maintain normal spatial memory. Deroualle and Lopez have explored the visual-vestibular interaction and in their 2014 review of the topic conclude that vestibular signals may be involved in the sensory bases of self-other distinction and mirroring, emotion perception and perspective taking. Clinically, patients with TWS recognize changes in their personality. Smith and Darlington argue that these changes in cognitive and emotional function occur because of the role the ascending vestibular pathways to the limbic system and neocortex play in the sense of spatial orientation. They further suggest that this change in the sense of self is responsible for the depersonalization and derealization symptoms such as feeling “spaced out,” “body feeling strange” and “not feeling in control of self.”

1.3.4. Anxiety

Vestibular disorders can produce anxiety; however, the classic sense of impending doom only occurs with the most severe gravitational receptor asymmetries. It is none-the-less unnerving to patients because it is a unique type of anxiety and characteristically patients have no insight why they feel that way or what is making them feel that way. Much work has been completed to understand the underlying mechanisms and pathways subserving this dysfunction.

1.3.5. Sound-Induced Gravitational Receptor Dysfunction Type of Vertigo

In Minor’s review of 65 patients with SSCD, 54 (83%) had vestibular symptoms elicited by loud sounds, and 44 (67%) had pressure-induced (sneezing, coughing, and straining) symptoms. This is also characteristic of TWS patients with other sites of dehiscence.

1.3.6. Autophony

In TWS one of the most disturbing auditory symptoms is autophony, an unpleasant subjective discomfort of one’s own voice during phonation. Often patients describe their voice as “echo-like” or “resonant.” This is also very common in TWS. Just as in the case with SSCD, some patients with other sites of dehiscence can also hear their eyes move or blink. There appears to be decreased hearing thresholds for bone-conducted sounds. Bhutta has postulated that patients who hear their eyes move do so via transdural transmission of extraocular muscle contraction. If this is the case, further credence to the hypothesis that some cases of CT– TWS represent an otic capsule defect in an area such as the modiolus creating a third window, just as is the case with SSCD and CFD.

1.3.7. Migraine and Gravitational Receptor Dysfunction Type of Vertigo

Migraine headache is nearly always present in patients with gravitational receptor dysfunction type of vertigo caused by a TWS, but infrequently with rotational receptor dysfunction type of true rotational vertigo. This is an important concept as TWS can induce or exacerbate migraine and the three variants of migraine – ocular migraine, hemiplegic migraine and vestibular migraine in affected patients. This is why patients with TWS, who normally only have gravitational receptor dysfunction type of vertigo (disequilibrium) can have episodes of vestibular migraine and infrequent true rotational vertigo attacks. Surgical management, based upon the procedure specific to the site of dehiscence typically resolves the migraine; however, sometimes there is a marked decrease of the frequency and intensity of the migraines, as migraine has a high incidence overall.

2. Headache and Migraine

Migraine is a symptomatically heterogeneous condition, of which headache is just one manifestation. Migraine is viewed as a disorder of altered sensory thresholding, with hypersensitivity among sufferers to sensory input. Advances in functional neuroimaging have highlighted that several brain areas are involved even prior to pain onset. Clinically, patients can experience symptoms hours to days prior to migraine pain, which can warn of impending headache. These symptoms can include mood and cognitive functional changes, fatigue, and neck discomfort. Epidemiological studies have suggested that migraine is associated with other systemic conditions such as depression, anxiety, irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, sleep disorders, and chronic fatigue, as well as cognitive disorders (for review see Karsan and Goadsby). The associations between migraine symptoms and psychiatric disorders have been well documented through numerous population-based studies. The results of these studies show an increased risk of diagnoses of depression, bipolar disorders, numerous anxiety disorders, especially posttraumatic stress disorder. Many reasons have been postulated for these associations, including comorbidities, cause and effect, and shared pathophysiological mechanisms. Sarif et al. completed a systematic review of the association of migraine and cognitive dysfunction, including dementia. All the reviewed studies showed an association between headache and cognitive dysfunction of any form. Furthermore, they suggested that the frequency and duration of headache is a determinant for dementia. However, few studies also focused on how treating headaches with certain drugs can lead to dementia. The reviewed published literature showed that dementia has been potentially linked with headaches of any sort and their treatment. As one of the most common chronic daily headache (CDH) disorders, chronic migraine (CM) is featured by frequent headache attacks with at least 15 headache days per month. Chronic migraine sufferers usually have a history of episodic migraine (EM) and their headache frequencies increase with time. It is estimated that approximately 3% of EM patients evolve to CM per year. This transformation can be bidirectional with about 26% of CM patients reverting to EM in a cohort followed for two-years. Because of this, it is difficult to confirm the true prevalence of CM. With the increasing headache frequency, CM can become less intense, but is associated with a worse response to treatment. Both the undertreated headache and associated comorbidities cause greater disease burden for CM compared with EM. Although regarded as the same spectrum illness with EM, the detailed pathophysiology of CM is not fully understood. The role of vestibular dysfunction due to TWS in EM and/or CM remains understudied. Studies have recognized several predisposing factors and triggers such as specific olfactory stimuli, sleep deprivation, hunger, bright light, medication overuse, insufficient migraine prophylactic treatment, low socioeconomic status, stressful events, and depression. In a series with three different TWS cohorts, depression, as measured with Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI), was significantly reduced after surgical management. These same cohorts had significant reduction in their Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) scores after surgical management underscoring the potential contribution of TWS to depression and migraine. Moreover, recent neurophysiological and imaging studies have indicated that CM may be associated with both structural and functional alterations in some brain regions, especially cortical hyperexcitability and brainstem dysfunction. Sensitization of the trigeminal system also plays a vital role, as allodynia is quite common in CM patients. In addition, several molecular mechanisms have been implicated in the pathogenesis of CM, such as calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), serotonin (5-HT), pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide (PACAP), and others. Migraine should be considered a neural disorder of brain function, in which alterations in networks integrating the limbic system with the sensory and homeostatic systems occur early and persist after headache resolution and perhaps interictally. The associations with some of these other disorders may allude to the inherent sensory sensitivity of the migraine-sufferer’s brain and shared neurobiology and neurotransmitter systems rather than true comorbidity.

A gerbil model of SSCD with reversible diagnostic findings characteristic of patients with the disorder has been developed. In addition, this animal model has demonstrated reversible impairments in specific auditory and visual behavioral tasks assessing decision-making, suggesting a potential link between vestibular dysfunction and cognitive deficits. These animals with SSCD also show reversible deficits in a spatial two alternative force choice (2AFC) task where they must make a left versus right decision to receive a food reward. In that same study Mowery et al. used neuroanatomical tracing to confirm a cross species (gerbil and mouse) vestibular behavioral circuit that modulates associative conditioned tasks through thalamic input to the striatum. Together, these findings show how important proper vestibular function is to normal behaviors. Most recently, Hong et al. used the same gerbil SSCD model to confirm that aberrant asymmetric vestibular output results in reversible balance impairments, similar to those observed in patients after SSCD plugging surgery. However, this model has not been used to study headache since the behavioral modeling has not been developed. Animal models of CM are complicated to develop; however, multiple methods have been used to induce recurrent headache-like behaviors or biochemical changes in rodents, including repeated dural application of inflammatory soup, chronic systemic infusion of nitroglycerin, repeated administration of acute migraine abortive treatment to simulate medication overuse headache, or genetic models. While these models do exhibit some of the features believed to be associated with migraine, none of the models can recapitulate all the clinical phenotypes found in humans and each has its own weakness. Other authors have reviewed behavioral models but depend on comorbid conditions such as anxiety and depression. Anxiety-like behaviors can be evaluated with the open-field, elevated plus-maze or light/dark box tests. Depressive behavior is assessed with the forced-swim or tail suspension tests. As we have demonstrated our SSCD model is associated with reversible decision-making and balance dysfunction which would make interpretation of the behavioral models of CM even more difficult.

2.1. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF CHRONIC MIGRAINE

Like EM, the pathophysiological basis of CM is not fully understood. However, recent data indicate that migraine is a disorder of brain dysfunction with both the genetic background and with environmental triggering. The transformation of EM to CM is also related to the brain. Recent evidence has demonstrated both structural and functional alterations in the brain, in particular cortical hyperexcitability and abnormalities in the brainstem. More CM patients than EM patients report cutaneous allodynia, suggesting that sensitization of trigeminal system is involved in the development of the disease. This sensitization could include referred sensations from the meninges, nasal and paranasal sinuses reported in classic intraoperative stimulation studies by Harold Wolff’s group. Seo and Park investigated the clinical significance of allodynia compared with other sensory hypersensitivities in migraine patients. They found that in migraine particularly combined with allodynia resulted in poor clinical outcomes. In addition, several molecules, such as CGRP and 5-HT, have been reported to be correlated with the transition from occasional migraine to EM and finally to CM. In brief, both recurring headache attacks and the comorbid conditions (medication over use, anxiety, and depression) promote the derangement of top-down pain modulation and atypical release of nociceptive molecules, which aggravates trigeminal sensitization induced by repeated nociceptive inputs. With this hypersensitive state, the EM finally progresses to CM. The neural plasticity induced by the risk factors of CM may influence themselves in turn. Recently, Cammarota et al. suggested that high-frequency EM may be a subtype clinically falling between EM and CM.

3. Measuring the Impact of Headache

When measuring the magnitude of headache and migraine headache in patients with TWS and equally importantly, the response to surgical intervention it is essential to incorporate a validated survey instrument into clinical practice. We have found the six-item HIT-6 to be an outstanding tool to accomplish these goals. The short-form HIT-6 is a widely used patient-reported outcome measure that assesses the negative effects of headaches on normal activity. Houts et al. completed a narrative literature review to examine existing qualitative research in patients with migraine and headache, and to provide insight into the relevance and meaningfulness of HIT-6 items to the lives of migraine patients. The review demonstrated qualitative support for the relevance of the items of the HIT-6 as a global metric of clinical impact in migraine patients, supporting its ongoing use in clinical migraine research and practice. The six-item HIT-6 includes the following questions: Question 1: When you have headaches, how often is the pain severe?; Question 2: How often do headaches limit your ability to do usual daily activities including household work, work, school, or social activities?; Question 3: When you have a headache, how often do you wish you could lie down?; Question 4: In the past 4 weeks, how often have you felt too tired to do work or daily activities because of your headaches?; Question 5: In the past 4 weeks, how often have you felt fed up or irritated because of your headaches?; Question 6: In the past 4 weeks, how often did headaches limit your ability to concentrate on work or daily activities? Each item has five descriptive response options, with each awarded a specific number of points: “Never” (6 points), “Rarely” (8 points), “Sometimes” (10 points), “Very often” (11 points) and “Always” (13 points). The score is the sum of item (points) responses. The index score ranges from 36 to 78, where scores 49 indicate little to no impact on life (Class I); 50–55 indicates some impact on life (Class II); 56–59 indicates substantial impact on life (Class III); and 60–78 indicates very severe impact on life (Class IV). Beyond these general impact categories, it is not clear that the HIT-6 raw score has either specificity or sensitivity for detecting more subtle changes in headache impact. There are alternative validated survey instruments such as the Chronic Headache Quality of Life Questionnaire (CHQLQ) which is a 14-item questionnaire, assessing the functional aspects of headache-related quality of life, producing three domain scores (role prevention, role restriction, and emotional function). Haywood et al. compared the quality and acceptability of a new headache-specific patient-reported measure, the CHQLQ, with the six-item HIT-6, in people meeting an epidemiological definition of chronic headaches. They concluded while both the HIT-6 and CHQLQ measures are structurally valid, internally consistent, temporally stable, and responsive to change, the CHQLQ has greater relevance to the patient experience of chronic headache. However, for the patient with TWS, the CHQLQ questions are too similar to the Dizziness Handicap Inventory domains (functional, physical and impact on disability) and it is likely that the TWS patients would answer the CHQLQ questions based upon their vestibular dysfunction symptoms/experiences. For this reason, we find the HIT-6 to be more useful in this specific patient population.

4. Headache and Migraine in Third Window Syndrome

It is common for patients with TWS to experience symptom complexes associated with headache and migraine headache. They can also experience the variants of migraine; vestibular migraine (VM), ocular migraine and hemiplegic migraine.

| Etiology of Third Mobile Window Syndrome and Cohort Studied | Chronic Headache / Migraine | 24/7 While Awake | Daily or Frequent | Occasional Headache | No Headache | Vestibular Migraine | Ocular Migraine | Hemiplegic Migraine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSCD with plugging (cohort 1) (Current series) | 80% (8/10) | 10% (1/10) | 80% (8/10) | 20% (2/10) | None | 60% (6/17) | 40% (4/10) | None |

| SSCD with plugging (cohort 2) Wackym et al. | 91% (10/11) | 9.1% (1/11) | 81.8% (9/11) | 9.1% (1/11) | 9.1% (1/11) | 9.1% (1/11) | None | |

| CT– with RWR Wackym et al. | 92.9% (13/14) | 71.4% (10/14) | 21.4% (3/14) | None | 7.1% (1/14) | 14.3% (2/14) | 21.4% (3/14) | 7.1% (1/14) |

| SSCD plugging + CT– with RWR Wackym et al. | 100% (4/4) | None | 100% (4/4) | None | None | None | 25% (1/4) | None |

| CFD with RWR Wackym et al. | 75% (6/8) | 25% (2/8) | 75% (6/8) | None | None | 37.5% (3/8) | 62.5% (5/8) | None |

| CFD without RWR Wackym et al. | 87.5% (7/8) | None | 75% (6/8) | 12.5% (1/8) | 12.5% (1/8) | 62.5% (5/8) | 25% (2/8) | None |

| PLF Black et al. | 88% (51/58) | NR | NR | NR | 12% (7/58) | NR | NR | NR |

Of note there were some TWS patients with no headache. In these same series the prevalence of no headache was 9.1% in SSCD with plugging, 7.1% in CT– RWR, 12.5% in CFD without RWR and 12% surgically managed PLF. The remaining cohorts all experienced headache preoperatively. Ward et al. reviewed the first 20 years of literature after SSCD and regarding migraine and SSCD they stated, “Many patients with [SSCD] also have migraine, but this may represent the high prevalence of migraine in the general population and that [SSCD] is an effective migraine trigger.” Another way of restating that is that SSCD, and other sites creating TWS, can induce migraine symptoms, in the same way that trigeminal nerve stimulation, olfactory stimulation and ocular stimulation can induce episodes of migraine. Of course, both possibilities can be true and using a validated survey instrument, the HIT-6, to measure the scores before and after surgical intervention is consistent with this perspective.

| Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) score preoperatively and postoperatively, statistical significance and preoperative and postoperative classification. | Mean preoperative HIT-6 score | Mean postoperative HIT-6 score | Statistical Significance (paired t-test) | Preoperative HIT-6 Classifications | Postoperative HIT-6 Classifications | Categorical Analysis (Chi-square or Fisher Exact) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSCD with plugging (cohort 1) (n=10) (n=9 with headache) (Current series) | 60.2 (range 36-72, SD ± 11.08) | 47.4 (range 36-63, SD ± 9.17) | p <0.001 | 8 Class IV, 1 Class III, 1 Class I | 1 Class IV, 5 Class II, 4 Class I | Chi-square (IV:III/II:I vs. Pre-Post) = 10.79, 2 df, p<0.01 |

| SSCD with plugging (cohort 2) (n=5) (n=4 with headache) (Wackym et al.) | 69.8 (range 61-76, SD ± 6.34) | 44.5 (range 36-61, SD ± 11.27) | p <0.001 | 4 Class IV, 1 Class I | 1 Class IV, 3 Class I | Sample small |

| CT– with RWR (n=8) (n=7 with headache) (Wackym et al.) | 74 (range 68-78, SD ± 4) | 45.7 (range 42-49, SD ± 3.14) | p <0.001 | 7 Class IV | 7 Class I | IV:I vs. Pre-Post; Fisher exact, p=0.0006 |

| SSCD plugging + CT– with RWR (n=4) (Wackym et al.) | 69.3 (range 57-78, SD ± 9.7) | 46.8 (range 36-53, SD ± 8.10) | p <0.001 | 3 Class IV, 1 Class III | 2 Class II, 2 Class I | Sample too small |

| CFD with RWR (n=8) (Wackym et al.) | 64.9 (range 52-69, SE ± 1.1) | 42.4 (range 36-55, SE ± 2.7) | p <0.001 | 8 Class IV | 1 Class III, 2 Class II, 5 Class I | Sample too small |

| COMBINED CASES | 30 Class IV, 2 Class III, 2 Class I | 2 Class IV, 1 Class III, 9 Class II, 21 Class 1 | Chi-square (IV:III/II:I vs. Pre-Post) = 45.52, 2 df, p<0.001 |

Patients with TWS can also experience symptoms of VM (migraine-associated dizziness) which is recognized as a distinct clinical entity that accounts for a high proportion of patients with vestibular symptoms (for review see Furman et al.). It is so common that VM should be considered in any patient presenting with dizziness, vertigo, or disequilibrium. A temporal overlap between vestibular symptoms, such as vertigo and head-movement intolerance, and migraine symptoms, such as headache, photophobia, and phonophobia, is a requisite diagnostic criterion. Physical examination and laboratory testing are usually normal in VM but can be used to rule out other vestibular disorders with overlapping symptoms such as TWS. The pathophysiology of VM is incompletely understood but plausibly could include neuroanatomical pathways to and from central vestibular structures and neurochemical modulation via the locus coeruleus and raphe nuclei. In the absence of controlled trials, treatment options for patients with VM largely mirror those for migraine headache. These treatment approaches include the prophylactic prevention of migraines with: 1) antiseizure medications such as topiramate (Topamax) or zonisamide (Zonegran); 2) calcium channel blockers such as verapamil (Verelan); 3) tricyclic antidepressants such as nortriptyline (Pamelor); or beta-blockers, for children, such as propranolol (Inderal). Approximately one-third of vestibular migraine patients have endolymphatic hydrops, which is typically bilateral.

![Figure 2. Preoperative (Preop) and postoperative (Postop) Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI) scores and Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) scores of 10 patients who underwent middle fossa plugging and resurfacing of their superior semicircular canal dehiscence. The mean age was 32.7 years (SE 3.73, range 13 – 64). There were 7 females and 3 males. A) Individual patient data for preoperative and postoperative DHI scores in the 10 patients included in this study. The preoperative mean DHI score was 48.9 (SE 4.9, range 18 – 84). The postoperative mean DHI score was 14.5 (SE 2.6, range 0 – 36). This improvement was highly statistically significant (Tukey Honest Significant Difference [Tukey HSD], p<0.001). Individual patients are plotted as separate lines (red). B) Individual patient data for preoperative and postoperative HIT-6 scores in 10 patients included in this study. The preoperative mean HIT-6 score was 60.2 (SE 2.7, range 36 – 72). The postoperative mean HIT-6 score was 47.4 (SE 2.2, range 36 – 63). This improvement was highly statistically significant (Tukey HSD, p<0.001). Individual patients are plotted as separate lines (red). Used with permission, copyright © P.A. Wackym, MD](/pdf-to-wp-converter/uploads/images/migraine-headache-third-window-syndrome-figure-2.png)

Patients with TWS can also experience symptoms of VM (migraine-associated dizziness) which is recognized as a distinct clinical entity that accounts for a high proportion of patients with vestibular symptoms (for review see Furman et al.). It is so common that VM should be considered in any patient presenting with dizziness, vertigo, or disequilibrium. A temporal overlap between vestibular symptoms, such as vertigo and head-movement intolerance, and migraine symptoms, such as headache, photophobia, and phonophobia, is a requisite diagnostic criterion. Physical examination and laboratory testing are usually normal in VM but can be used to rule out other vestibular disorders with overlapping symptoms such as TWS. The pathophysiology of VM is incompletely understood but plausibly could include neuroanatomical pathways to and from central vestibular structures and neurochemical modulation via the locus coeruleus and raphe nuclei. In the absence of controlled trials, treatment options for patients with VM largely mirror those for migraine headache. These treatment approaches include the prophylactic prevention of migraines with: 1) antiseizure medications such as topiramate (Topamax) or zonisamide (Zonegran); 2) calcium channel blockers such as verapamil (Verelan); 3) tricyclic antidepressants such as nortriptyline (Pamelor); or beta-blockers, for children, such as propranolol (Inderal). Approximately one-third of vestibular migraine patients have endolymphatic hydrops, which is typically bilateral.

5. Summary

Migraine is a symptomatically heterogeneous condition, of which headache is just one manifestation. This disorder is associated with altered sensory thresholding, with hypersensitivity among migraine sufferers to different sensory inputs. Hence, we suggest that sensitivity to the gravitational receptor asymmetries seen in TWS is triggering migraine symptoms via this hypersensitivity-associated mechanism. When measuring the impact of headache and migraine headache in the lives of patients with third window syndrome as well as the response to surgical intervention it is essential to incorporate a validated survey instrument into clinical practice. We have found that the six-item HIT-6 in several different cohorts has demonstrated a highly statistically significant symptom improvement after surgical management of patients with TWS.

References

- Merchant, S.N., & Rosowski, J.J. (2008). Conductive hearing loss caused by third-window lesions of the inner ear. Otol Neurotol. 29:282–89. doi: 10.1097/mao.0b013e318161ab24

- Stenfelt, S., & Goode, R.L. (2005). Bone-conducted sound: physiological and clinical aspects. Otol Neurotol 26:1245–46. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000187236.10842.d5

- Black, F.O., Pesznecker, S., Norton, T., et al. (1992). Surgical management of perilymphatic fistulas: a Portland experience. Am J Otol 13:254–62.

- Wackym, P.A., Balaban, C.D., Mowery, T.M. (2023). History and overview of third mobile window syndrome. In: G.J. Gianoli, P. Thomson (Eds.), Third Mobile Window Syndrome of the Inner Ear. Springer Nature, Switzerland AG, pp. 3-25.

- Mowery, T.M., Balaban, C.D., Wackym, P.A. (2023). The cognitive/psychological effects of third mobile window syndrome. In: G.J. Gianoli, P. Thomson (Eds.), Third Mobile Window Syndrome of the Inner Ear. Springer Nature, Switzerland AG, pp. 107-119.

- Naert, L., Van de Berg, R., Van de Heyning, P., et al. (2018). Aggregating the symptoms of superior semicircular canal dehiscence syndrome. Laryngoscope 128(8):1932-1938. doi: 10.1002/lary.27062

- Wackym, P.A., Balaban, C.D., Zhang, P., Siker, D.A., Hundal, J.S. Third window syndrome: surgical management of cochlea-facial dehiscence. Front Neurology 2019;10:1281. doi:10.3389/fneur.2019.01281

- Kohut, R.I. (1992). Perilymph fistulas. Clinical criteria. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 118(7):687-92. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1992.01880070017003

- Wackym, P.A. (2012). Vestibular migraine. Patient video describing symptoms before and after treatment with Topamax. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zy7YjCDnLYM. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.1.3096.2647. Published 12 April 2012. (Accessed 1 January 2025). Copyright © P.A. Wackym, MD, used with permission.

- Wackym, P.A. (2012). Right perilymph fistula not superior canal dehiscence. Patient video describing symptoms before and after surgical repair. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bDph0B0uLbg. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.1.3097.8000. Published 12 November 2012. (Accessed 1 January 2025). Copyright © P.A. Wackym, MD, used with permission.

- Wackym, P.A. (2019). Right cochlea-facial nerve dehiscence: 16 year old thought to have conversion disorder. https://youtu.be/fTjsnnUALBw. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.27418.90564. Published 14 April 2019. (Accessed 1 January 2025). Copyright © P.A. Wackym, MD, used with permission.

- Wackym, P.A. (2012). Perilymph fistula. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jSAM6h-7Mwc. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.1.1000.6488. Published 15 April 2012. (Accessed 1 January 2025). Copyright © P.A. Wackym, MD, used with permission.

- Wackym, P.A. (2017). Right superior semicircular canal dehiscence repair: Symptoms and recovery. https://youtu.be/er4k8NZrG2I. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.32032.79361. Published 9 January 2017. (Accessed 1 January 2025). Copyright © P.A. Wackym, MD, used with permission.

- Wackym, P.A. (2017). Recurrent third window syndrome co-morbidity: Functional neurological symptom disorder. https://youtu.be/AgUy07QxTxo. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.15255.57763. Published 9 January 2017. (Accessed 1 January 2025). Copyright © P.A. Wackym, MD, used with permission.

- Wackym, P.A. (2015). Otic capsule dehiscence syndrome in one ear after a car accident. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Nl9T6etxqM. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.1.3359.9440. Published 5 April 2015. (Accessed 1 January 2025). Copyright © P.A. Wackym, MD, used with permission.

- Wackym, P.A. (2019). Cochlea-facial nerve dehiscence: Traumatic third window syndrome after a snowboarding accident. https://youtu.be/NCDMD5FGf-w. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.17283.76327. Published 9 April 2019. (Accessed 1 January 2025). Copyright © P.A. Wackym, MD, used with permission.

- Wackym, P.A. (2019). Surgery for cochlea-facial nerve dehiscence: Symptoms and tuning fork testing. https://youtu.be/lFR-zdYlIsY. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.34129.79209. Published 14 April 2019. (Accessed 1 January 2025). Copyright © P.A. Wackym, MD, used with permission.

- Wackym, P.A. (2015). Tuning fork testing in otic capsule dehiscence syndrome. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Szp_kO8oVos. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.1.4408.5204. Published 21 April 2015. (Accessed 1 January 2025). Copyright © P.A. Wackym, MD, used with permission.

- Wackym, P.A. (2015). Tuning fork testing before and after repair of two types of otic capsule dehiscence. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NIauJPbvSpA. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.1.4365.7048. Published 13 December 2015. (Accessed 1 January 2025). Copyright © P.A. Wackym, MD, used with permission.

- Wackym, P.A., Wood, S.J., Siker, D.A., Carter, D.M. (2015). Otic capsule dehiscence syndrome: Superior canal dehiscence syndrome with no radiographically visible dehiscence. Ear Nose Throat J 94(7):E8-24. doi: 10.1177/014556131509400802

- Wackym, P.A., Balaban, C.D., Mackay, H.T., et al. (2016). Longitudinal cognitive and neurobehavioral functional outcomes after repairing otic capsule dehiscence. Otol Neurotol 37(1):70-82. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000928

- Wackym, P.A., Mackay-Promitas, H.T., Demirel, S., et al. (2017). Comorbidities confounding the outcomes of surgery for third window syndrome: Outlier analysis. Laryngoscope Invest Otolaryngol 2(5):225-253. doi: 10.1002/lio2.89

- Minor, L.B., Solomon, D., Zinreich, J.S., Zee, D.S. (1998). Sound- and/or pressure-induced vertigo due to bone dehiscence of the superior semicircular canal. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 124(3): 249-58. doi: 10.1001/archotol.124.3.249

- Minor, L.B. (2005). Clinical manifestations of superior semicircular canal dehiscence. Laryngoscope. 115:b1717–1727. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000178324.55729.b7.

- Wackym, P.A., Agrawal, Y., Ikezono, T., Balaban, C.D. (2021). Editorial: Third Window Syndrome. Front Neurol. 12: 704095. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.704095.

- Ward, B.K., Carey, J.P., Minor, L.B. (2017). Superior canal dehiscence syndrome: lessons from the first 20 years. Front Neurol. 8: 177. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00177.

- Wackym, P.A., & Balaban, C.D. (1998). Molecules, motion, and man. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 118:S15-S23.

- Balaban, C.D., & Thayer, J.F. (2001). Neurological bases for balance-anxiety links. J Anxiety Disord 15(1-2):53-79. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(00)00042-6

- Balaban, C.D., McGee, D.M., Zhou, J., Scudder, C.A. (2002). Responses of primate caudal parabrachial nucleus and Kölliker-fuse nucleus neurons to whole body rotation. J Neurophysiol 88:3175–93. doi: 10.1152/jn.00499.2002

- Balaban, C.D. (2004). Projections from the parabrachial nucleus to the vestibular nuclei: potential substrates for autonomic and limbic influences on vestibular responses. Brain Res 996(1):126-37. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.10.026

- Baek, J.H., Zheng, Y., Darlington, C.L., Smith, P.F. (2010). Evidence that spatial memory deficits following bilateral vestibular deafferentation in rats are probably permanent. Neurobiol Learn Mem 94(3):402-13. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2010.08.007

- Smith, P.F., Darlington, C.L., Zheng, Y. (2010). Move it or lose it–is stimulation of the vestibular system necessary for normal spatial memory? Hippocampus 20(1):36-43. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20588

- Deroualle, D., & Lopez, C. (2014). Toward a vestibular contribution to social cognition. Front Integr Neurosci 8:16. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2014.00016

- Smith, P.F., & Darlington, C.L. (2013). Personality changes in patients with vestibular dysfunction. Front Hum Neurosci 7:678. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00678

- Darlington, C.L., Goddard, M., Zheng, Y., Smith, P.F. (2009). Anxiety-related behavior and biogenic amine pathways in the rat following bilateral vestibular lesions. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1164:134-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2008.03725.x

- Crane, B.T., Lin, F.R., Minor, L.B., Carey, J.P. (2010). Improvement in autophony symptoms after superior canal dehiscence repair. Otol Neurotol 31(1):140-6.

- Bhutta, M.F. (2015). Eye movement autophony in superior semicircular canal dehiscence syndrome may be caused by trans-dural transmission of extraocular muscle contraction. Int J Audiol 54(1):61-2.

- Messina, R., Gollion, C., Christensen, R.H., Amin, F.M. (2022). Functional MRI in migraine. Curr Opin Neurol. 35(3): 328-335. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000001060.

- Karsan, N., & Goadsby, P.J. (2021). Migraine is more than just headache: is the link to chronic fatigue and mood disorders simply due to shared biological systems? Front Hum Neurosci. 15: 646692. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2021.646692.

- Radat, F. (2021). What is the link between migraine and psychiatric disorders? From epidemiology to therapeutics. Rev Neurol (Paris). 177(7): 821-826. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2021.07.007.

- Sharif, S., Saleem, A., Koumadoraki, E., Jarvis, S., Madouros, N., Khan, S. (2021). Headache – a window to dementia: an unexpected twist. Cureus. 13(2): e13398. doi: 10.7759/cureus.13398.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). (2018). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 38(1): 1-211. doi: 10.1177/0333102417738202

- Su, M., Yu, S. (2018). Chronic migraine: a process of dysmodulation and sensitization. Mol Pain. 14: 1744806918767697. doi: 10.1177/1744806918767697.

- Lipton, R.B., Fanning, K.M., Serrano, D., Reed, M.L., Cady, R., Buse, D.C. (2015). Ineffective acute treatment of episodic migraine is associated with new-onset chronic migraine. Neurology. 84(7): 688-95. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001256.

- Scher, A.I., Buse, D.C., Fanning, K.M., et al. (2017). Comorbid pain and migraine chronicity: the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes Study. Neurology. 89(5): 461-468. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004177.

- Manack, A., Buse, D.C., Serrano, D., Turkel, C.C., Lipton, R.B. (2011). Rates, predictors, and consequences of remission from chronic migraine to episodic migraine. Neurology. 76(8): 711-8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820d8af2.

- Adams, A.M., Serrano, D., Buse, D.C., et al. (2015). The impact of chronic migraine: The Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) Study methods and baseline results. Cephalalgia. 35(7): 563-78. doi: 10.1177/0333102414552532.

- Lipton, R.B., Manack Adams, A., Buse, D.C., Fanning, K.M., Reed, M.L. (2016). A comparison of the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) Study and American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study: Demographics and Headache-Related Disability. Headache. 56(8): 1280-9. doi: 10.1111/head.12878.

- Buse, D.C., Manack, A., Serrano, D., Turkel, C., Lipton, R.B. (2010). Sociodemographic and comorbidity profiles of chronic migraine and episodic migraine sufferers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 81(4): 428-32. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.192492.

- Aurora, S.K. (2009). Spectrum of illness: understanding biological patterns and relationships in chronic migraine. Neurology. 72(5 Suppl): S8-13. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31819749fd.

- Cho, S.J., Chu, M.K. (2015). Risk factors of chronic daily headache or chronic migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 19(1): 465. doi: 10.1007/s11916-014-0465-9.

- Aurora, S.K., Barrodale, P.M., Tipton, R.L., Khodavirdi, A. (2007). Brainstem dysfunction in chronic migraine as evidenced by neurophysiological and positron emission tomography studies. Headache. 47(7): 996-1003; discussion 1004-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00853.x

- Lai, T.H., Chou, K.H., Fuh, J.L., et al. (2016). Gray matter changes related to medication overuse in patients with chronic migraine. Cephalalgia. 36(14): 1324-1333. doi: 10.1177/0333102416630593.

- Mathew, N.T. (2011). Pathophysiology of chronic migraine and mode of action of preventive medications. Headache. 51 Suppl 2: 84-92. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01955.x.