Misconceptions in Shock Wave and Pressure Wave Therapy

“`html

Clarifying misconceptions in the medical use of shock waves and radial pressure waves: Insights into common errors and the physical principles behind them

Achim M. Loske

Centro de Física Aplicada y Tecnología Avanzada, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Boulevard Juriquilla 3001, Querétaro, Qro. 76230, México.

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED 31 August 2025

CITATION Loske, AM., 2025. Clarifying misconceptions in the medical use of shock waves and radial pressure waves: Insights into common errors and the physical principles behind them. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(8). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i8.6799

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i8.6799

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

The clinical use of shock waves has evolved surprisingly since their introduction for kidney stone fragmentation in 1980, expanding into diverse fields including orthopedics, cardiology, dermatology, and erectile dysfunction. Emerging applications, such as Alzheimer’s disease therapy, appear promising. Despite this broad acceptance, the physical and biological mechanisms behind their therapeutic effects are not yet fully understood, particularly regarding the relevance of specific physical parameters. The introduction of devices that generate radial pressure waves has broadened the use of extracorporeal pressure wave therapy. However, it has also caused confusion about the distinction between shock waves and radial pressure waves. This has led to inconsistencies in protocol design, and outcome interpretation, ultimately hindering clinical progress. This article presents a physics-based overview of shock waves and radial pressure waves, focusing on their propagation through biological tissues and the associated secondary effects. Key parameters, such as energy flux density, focal zones, and impulse, are defined and contextualized to support accurate reporting. Emphasis is placed on the correct use of terminology, adherence to international standards, and the importance of proper training for healthcare providers using these technologies. Several common errors are analyzed, including issues related to pressure wave coupling, patient positioning, parameter selection, and improper device operation. By clarifying some physical principles and addressing common misunderstandings, this article aims to enhance the safe and effective use of extracorporeal pressure wave therapies. It advocates for a more rigorous approach to terminology, parameter reporting, and clinical implementation, with the goal of enhancing treatment outcomes.

Keywords

Shock waves; Radial pressure waves; Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy; Extracorporeal shock wave therapy.

THE EUROPEAN SOCIETY OF MEDICINE

Medical Research Archives, Volume 13 Issue 8

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Abbreviations

- ESWL: Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy

- EPWT: Extracorporeal pressure wave therapy

- ESWT: Extracorporeal shock wave therapy

- SWL: Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy

- FSWT: Focused shock wave therapy

- RSWT: Radial shock wave therapy

- PSWT: Planar shock wave therapy

- ISMST: International Society for Medical Shockwave Treatment

- IFSWT: International Federation of Shock Wave Treatment

- RESWT: Radial extracorporeal shock wave therapy

- RPWT: Radial pressure wave therapy

- EFD: Energy flux density

- IEC: International Electrotechnical Commission

- TPS: Transcranial pulse stimulation

Introduction

Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) remains a first-line option for a significant proportion of patients with urinary stone disease. Since the early days of ESWL, shock waves have been successfully applied to an ever-growing range of medical conditions. Nevertheless, several misconceptions regarding their physical properties persist within the medical community. These misunderstandings have been passed down over the years, compromising clinical outcomes, limiting the reproducibility of treatment protocols and the optimization of therapeutic methodologies. A contributing factor is that many physical characteristics of shock waves are counterintuitive. In addition, the definitions of key parameters and the procedures for their measurement are not straightforward.

The wide range of clinical applications of shock waves complicates the overall picture. Whether targeting the fragmentation of calculi, the stimulation of cellular processes, or the alleviation of pain, different devices, settings, and treatment protocols must be used to enhance specific secondary effects. The emergence of devices that generate a different type of longitudinal wave -radial pressure waves- for the extracorporeal treatment of various conditions has further contributed to confusion, particularly because, in certain cases, either type of wave may be employed.

This article presents a physics-based overview of the fundamental characteristics of shock waves and radial pressure waves, including the most relevant parameters and their interaction with living tissues. Its primary goal is to identify and clarify common errors and controversies related to device descriptions, terminology usage, methodological implementation, and the reporting of clinical outcomes in ESWL and extracorporeal pressure wave therapy (EPWT). Misuse of terminology can hinder the optimization of clinical protocols, while incorrect device operation may compromise treatment efficacy with possible risks to patient safety. By addressing these issues, the article seeks to promote safer and more effective clinical practice.

It begins with theoretical concepts related to shock waves and radial pressure waves, including their propagation through biological tissue and the primary and secondary effects resulting from their reflection and transmission. The article then provides key definitions and describes the most used parameters. This is followed by a discussion of frequent errors that may arise during EPWT. The theoretical sections and accompanying illustrations have been simplified for clarity. Readers seeking more technical or in-depth information are encouraged to consult the references provided at the end of the article.

Brief theoretical background

SHOCK WAVES AND RADIAL PRESSURE WAVES

A shock wave is a sonic pulse, i.e. a sudden high-pressure disturbance. Although it is not a phenomenon like the one we might imagine when hearing the word “wave,” its characteristics place it within a group known as longitudinal waves, because they cause the particles of the medium to move in the same direction the wave travels. One aspect to keep in mind as a physician is that, although the particles do not travel with the wave, they do oscillate around an equilibrium position. A shock wave compresses and decompresses the tissue, causing variations in density. What is transmitted from one place to another is energy, not matter.

Shock waves used in ESWL and ESWT are commonly illustrated with a pressure-versus-time graph, like the one shown in

. A peculiarity of shock waves is that the compression and decompression are extremely fast, causing both desired and non-desired effects. Normally, little attention is given to how rapidly the pressure changes or to the magnitude of that change. Moreover, it is often overlooked that this graph only represents the pressure profile at the focal point and in water. It is not the same as the one experienced by the target inside the body. As the shock wave travels through tissue, its shape becomes distorted. This distortion arises partly because biological tissues are not homogeneous, and partly because the wave’s speed depends on its frequency. Since the compression phase contains higher frequencies, it tends to lose amplitude more quickly with distance than the lower-frequency negative phase, also known as the rarefaction phase.

As with

, radial pressure waves are often described with a graph of a compression of the medium followed by a rarefaction. To highlight the difference between both waveforms,

shows an overlay of the pressure variations produced by (a) the shock wave (purple curve) and (b) those generated by the radial pressure wave (red curve) over the first 200 nanoseconds. The shock wave reaches its peak amplitude (40 MPa) in just 3 nanoseconds, while the radial pressure wave remains nearly flat during the same time. It takes at least 200 nanoseconds for the latter to reach a pressure of barely 2 MPa. To illustrate how abrupt the onset of a shock wave is, consider that in 3 nanoseconds, a rifle bullet traveling at 800 m/s would cover only 2.4 micrometers. This is about 5% of the thickness of a human hair! The difference between the purple and red curves is crucial, as most of the biological effects and secondary phenomena involved in ESWL and EPWT depend on how rapidly the pressure changes occur. Both shock waves and radial pressure waves are disturbances with fluctuations that have been smoothed out in

.

By comparing the pressure variations shown in

and

, it becomes clear that, although both are longitudinal waves, they are fundamentally different disturbances. Shock waves sources for ESWL generate compression pulses between approximately 10 and 150 MPa, followed by rarefaction pulses reaching 30 MPa. For ESWT, shock waves with positive and negative pulses of less than half that values are commonly used. Ballistic equipment produces pressure peaks of up to approximately 15 MPa with rise times of a few microseconds.

TERMINOLOGY

Over time, the term extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL or SWL) has been correctly established to describe the non-invasive fragmentation of urinary stones. Unfortunately, the expression extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) has come to include both shock wave therapy and treatments using radial pressure waves.

Many authors and manufacturers refer to three types of therapy: radial shock wave therapy (RSWT), planar shock wave therapy (PSWT), and focused shock wave therapy (FSWT). The first term is technically inaccurate, as it is used to refer to radially propagating pressure waves not to radially propagating shock waves. Although radially expanding shock waves do exist, they are typically not used for transmission through the patient’s body. In electrohydraulic systems, as well as in the very rarely used devices that employ microexplosives for ESWL, shock waves initially propagate in a radial or spherical pattern. In the former, they are produced by the rapid expansion of the plasma bubble formed between two electrodes; in the latter, by plasma generated from the detonation of a microexplosive. In both cases, the waves originate at the first focus (F1) of a metallic ellipsoidal reflector, where they are reflected and lose their spherical geometry. As they converge at the second focus (F2), they become concentrated and are thus referred to as focused shock waves.

The term planar shock wave therapy may lead to the wrong idea that all planar waves used in extracorporeal therapy are shock waves; however, only those waves emitted by some systems meet the shock wave criteria (nearly instantaneous rise in pressure, high peak positive pressure, very short rise time, and supersonic propagation speed). Expressions such as extracorporeal ballistic shock wave therapy are also incorrect.

To avoid further promoting the incorrect use of the acronym ESWT, this article will use the term “extracorporeal pressure wave therapy” (EPWT) when referring to the therapy in general, “radial pressure wave therapy” (RPWT) for treatments performed with ballistic devices, and ESWT only when actual shock waves are applied. In this context, the word “wave” refers to a pressure pulse consisting of a positive phase followed by a negative or rarefaction phase. In other words, it includes half a positive cycle and half a negative cycle.

When the first ballistic devices entered the market, many authors referred to them as radial shock wave generators. Later, organizations like the International Society for Medical Shockwave Treatment (ISMST) and the International Federation of Shock Wave Treatment (IFSWT) clarified that these systems do not generate shock waves. Despite this, the term continues to appear in scientific articles, Internet sites, and advertising materials. The reluctance to adopt the correct terminology may stem from the perception that shock waves are “better” than radial pressure waves. In truth, neither is more effective. Their suitability depends on the specific clinical application. Some authors try to sidestep the issue by using the term radial “shock waves,” that is, using quotation marks; however, this is inconvenient, as it reinforces the misleading notion that both pressure waveforms are similar. Other sources simply refer to both types of perturbations as “short intense sound waves,” which is not incorrect; however, it gives the impression that they are alike phenomena. The term could even be mistaken for ultrasound. When a device emits only a few sinusoidal cycles, which is common in ultrasound imaging, it is referred to as a sound pulse.

Another inaccuracy, arising from the historical development of ESWL, is the use of “F2” to refer to the geometric focus, the spot of maximum pressure, or the point where the urinary stone to be fragmented should be positioned in piezoelectric or electromagnetic shock wave generators. This mistake has no impact on clinical treatments, but the terminology is inaccurate and should be avoided in publications. Only generators with paraellipsoidal reflectors, such as electrohydraulic devices, have two focal points, typically referred to as F1 and F2.

The spot where the positive pressure pulse reaches its maximum within the entire pressure field is known as the dynamic focus, or acoustic focus. This point usually does not match the geometric focus. In any case, shock waves do not concentrate at a single point. Regardless of the above, the focal point F is not necessarily the location of peak pressure. For practical purposes, the distance between the geometric focus and the point of maximum pressure is generally negligible, therefore, no distinction will be made between them in this text.

PROPAGATION THROUGH TISSUE

Studying the behavior of pressure waves as they pass through non-homogeneous and irregular interfaces, such as those found in the human body, is a complex task. When a mechanical wave encounters the boundary between two media with different physical properties, part of it is reflected, while the rest continues into the second medium, often with a change in direction. Waves also scatter due to the presence of small particles or structural irregularities. This must be considered to ensure that shock waves effectively reach the target area.

Reflection and refraction are particularly evident at interfaces where the acoustic impedance, that is, the resistance a medium offers to the passage of mechanical waves (product of the density of the medium by the speed of sound within it), changes abruptly. The reflection of shock waves at interfaces within the body generates forces of varying intensity and direction. These forces are fundamental to both the fragmentation of concrements and the induction of mechanotransduction. Since the affected structures are not freely suspended but connected to surrounding tissue, the resulting tensile and shear stresses stretch and compress cells and membranes until the motion is dampened by nearby tissue.

When passing through bone or impinging urinary calculi, both longitudinal and transverse waves can be generated. In ESWL, the most relevant physical phenomena are acoustic cavitation, compression, tensile stress, shear, fatigue, and the Hopkinson effect. Most of these processes occur simultaneously.

Shock waves and radial pressure waves behave differently as they travel through tissue. Only shock waves can deliver a significant amount of energy several centimeters deep into the body. Radial pressure waves act almost exclusively at the surface. Using radial pressure waves to treat deep-seated conditions is senseless.

During ESWL or ESWT procedures, it is important to remember that when a wave propagates from a medium with higher acoustic impedance to one with lower impedance, such as from soft tissue to air, the pressure pulse is inverted and reflected as a rarefaction. This inversion increases the risk of tissue damage due to cavitation and tearing. For this reason, directing pressure waves toward air-filled cavities, such as the lungs, can be hazardous.

In clinical applications that rely on ultrasound imaging, it is useful to consider that shock waves and ultrasound do not follow the same path. Furthermore, the position and size of the focal zone may differ from the values reported by the manufacturer, which are typically based on measurements in ideal conditions such as water or uniform viscous fluids. This phenomenon is not related to the projection deviations described later in the PATIENT POSITIONING section.

To ensure efficient energy transfer, clinical devices use gels and membranes with acoustic properties similar to those of water. This enables shock waves to couple effectively with soft tissue. A critical factor for successful treatment is maintaining this coupling throughout the entire session. If shock waves encounter air bubbles trapped in the gel between the transducer and the patient’s skin, a substantial portion of the energy will be reflected. This effect is often underestimated, yet it can significantly reduce the effectiveness of the therapy.

ACOUSTIC CAVITATION

The growth and collapse of microbubbles in a fluid, triggered by a passing mechanical wave, a phenomenon known as acoustic cavitation, plays an important role in both ESWL and ESWT. Cavitation can produce beneficial effects, such as stone fragmentation and activation of axons, but may also cause tissue damage. It typically originates from pre-existing microbubbles or cavitation nuclei and there is evidence that it can also occur in soft tissues. Its impact depends on several factors, including the type of tissue, the number and frequency of pulses, and the pressure profile of the applied wave.

Cavitation occurs when the positive pressure pulse of a shock wave compresses microbubbles. The following rarefaction phase and the high pressure inside the bubbles cause them to expand until they collapse violently within a few hundred microseconds. This collapse is so intense that it generates fluid microjets and secondary shock waves. Although microjets act over very short distances, they can reach extremely high velocities and can cause localized tissue damage.

Although cavitation has been observed in the renal parenchyma, soft tissues generally contain fewer gas bubbles and cavitation nuclei than body fluids. Therefore, whenever possible, it is advisable to create a fluid-filled expansion chamber around the stone, ensuring that at least part of its surface remains in direct contact with liquid. This environment promotes the growth and collapse of microbubbles, as well as the emission of microjets that contribute to stone fragmentation.

Since cavitation can also damage blood vessels and surrounding tissue, accurate positioning of the stone is essential.

shows a simplified schematic highlighting key elements to consider during an ESWL procedure. A shock wave, propagating in the indicated direction, strikes a urinary stone positioned at the lithotripter’s focal point (F). Surrounding part of the stone is a fluid-filled expansion chamber, that promotes the formation and collapse of microbubbles. This process generates microjets (not shown) that contribute to the fragmentation of the stone into smaller pieces. On the rear side of the stone, additional fragmentation occurs due to the Hopkinson effect (spalling).

does not include other relevant mechanisms that also play a role in ESWL-induced fragmentation, such as superfocusing and circumferential squeezing.

Ballistic devices can emit radial pressure waves with rarefaction phases (negative pressure) strong enough to induce acoustic cavitation. For this reason, they should only be operated by certified personnel, contraindications must be carefully observed, and they should not be used as if they were massage tools.

SHOCK AND RADIAL PRESSURE WAVE GENERATION

To ensure proper application of treatments involving shock waves and radial pressure waves, it is essential to understand how the devices operate and what their specific characteristics are. Although general descriptions are available in the literature, it is strongly recommended to consult the technical specifications and operating guidelines provided by the manufacturer of the equipment in use. This recommendation also applies to imaging and patient positioning systems, which are especially important in lithotripsy.

For ESWL and ESWT, shock waves are typically generated using electrohydraulic, piezoelectric, or electromagnetic transducers. Although other shock wave generation principles, such as microexplosives and multichannel discharge systems have also been proposed, their use has remained limited.

Electrohydraulic shock wave generators were the first to be used in ESWL. These devices are designed to produce a high-voltage electrical discharge in water between two electrodes, positioned at the first focus (F1) of a metallic ellipsoidal reflector. The discharge creates a rapidly expanding plasma, which generates a spherical shock wave. This wave reflects off the metallic surface and is concentrated at the second geometric focus (F2) of the reflector.

Piezoelectric systems produce shock waves using a set of polarized ceramic elements, that expand and contract a few micrometers in response to a high-voltage discharge. Dozens or even several hundred piezoelectric elements are mounted on the inner surface of a spherical metallic shell inside a fluid-filled chamber. When activated, each element rapidly expands, emitting a high-pressure pulse directed toward the center of the assembly, typically referred to as the focus (F). The superposition of the pressure pulses, along with nonlinear propagation effects, gives rise to a shock wave near the focal region.

In the past, the small focal zone of piezoelectric lithotripters was considered a disadvantage; however, it was later demonstrated that these systems can be highly effective when precise positioning is ensured. In most cases, shock waves are focused on a relatively small region. However, for certain ESWT applications, devices are designed to generate pressure waves that propagate as flat or cylindrical wavefronts. Some piezoelectric systems employ a dual-layer configuration in which piezo elements are bonded to both the front and rear sides of a metallic hemisphere. The outer array is triggered first, followed by the inner array, so that their outputs combine constructively. This increases the emitted energy and allows for a significant reduction in the diameter of the shock wave generator. Handheld transducers incorporating this double-layer technology are available on the market for ESWT. Other systems use a single piezoelectric crystal. When an electric discharge is applied, the crystal deforms and generates a pressure wave, which is then focused by an acoustic lens.

Electromagnetic shock wave sources are also widely used today and are available in two main designs: flat-coil and cylindrical-coil types. In the flat-coil version, a high-voltage pulse is delivered to a circular coil, generating a magnetic field that repels a metallic membrane. The sudden displacement of the membrane sends a pressure wave into the surrounding fluid. An acoustic lens then focuses the wave, which steepens into a shock wave near the focal point. In the cylindrical-coil design, the coil is placed around a metallic membrane housed within a parabolic reflector. When a high-voltage pulse is applied, the coil produces a magnetic field that pushes the membrane outward. The resulting acoustic wave propagates radially, reflects off the parabolic surface, and is concentrated at the system’s focal point.

As with piezoelectric shock wave sources, the relatively small focal zone of most electromagnetic lithotripters requires precise patient positioning.

Radial pressure waves are commonly produced by ballistic devices -either pneumatic or electromagnetic. In pneumatic systems, compressed air accelerates a projectile of approximately 5 to 10 grams inside a cylindrical guiding tube about 50 to 100 centimeters long. A pressure pulse, like the one shown in

, is generated when the projectile hits the applicator at the end of the tube. The impact is cushioned by a damping system. The part of the applicator that comes into contact with the patient’s skin can be flat, concave, or convex. Most manufacturers offer devices with a variety of interchangeable applicators to suit different treatment areas.

In electromagnetic pressure pulse generators, a solenoid is suddenly activated to produce a strong magnetic field that propels the projectile toward the end of the guiding tube, where it strikes the applicator. These systems do not require an air compressor, which is one reason why, when reporting clinical outcomes with pneumatic devices, it is not enough to provide only the air pressure, number of pulses, and pulse rate.

Some medical devices used in EPWT include transducers to generate both shock waves and radial pressure waves, either with separate modules or in a combined system. Choosing between one system and the other should be done with full awareness of the implications.

For the purposes of this article, the focus is placed less on the technical details of how pressure waves are generated and more on the characteristics of the resulting pressure field. Readers interested in the various generation methods will find relevant information in the references listed at the end of the article.

FOCAL ZONES

Another concept often used to compare devices and reports is that of focal zones. Most definitions originate from ESWL. When referring to the focal zone of a shock wave generator, it is important to specify which type of focal zone is meant, since their sizes can vary significantly and each one was defined for a particular purpose. The most widely used is the so-called -6 dB focal zone, defined as the volume within which the peak positive pressure reaches at least 50% of the maximum. It is worth noting that pressures outside this region may still be high enough to produce both desired and non-desired effects. Other commonly reported focal zones are those defined by 5 MPa and 10 MPa thresholds, i.e., volumes where the positive pressure equals or exceeds 5 and 10 MPa, respectively. In extracorporeal lithotripters, these focal zones typically resemble the shape of a cigar, with the longest axis aligned with the beam axis. The -6 dB focal zone provides insight into how shock waves are focused. A pressure of 5 MPa has been considered as the minimum threshold for triggering biological effects; however, there is no scientific evidence to support this. The 10 MPa region, on the other hand, is thought to correspond to the minimum pressure needed to fragment urinary stones. Increasing the energy output enlarges the 5 and 10 MPa focal zones, whereas the -6 dB region remains essentially unchanged. When a lithotripter with two shock wave heads operates in simultaneous mode, the focal region results from the overlap of two ellipsoidal volumes. In this configuration, the standard definitions of focal zones are no longer applicable.

PARAMETERS AND THEIR SIGNIFICANCE

In EPWT, defining and measuring treatment efficiency, as well as identifying which parameters are most relevant, is challenging and highly dependent on the specific application. Clinical outcomes are influenced by multiple factors, many of which still have unclear roles. This makes it especially important to report the technical specifications of the device and the parameters used, so that protocols can be compared, reproduced and optimized.

Since stone fragmentation primarily involves physical processes rather than complex biological interactions, in the case of ESWL, experience has made it possible to identify the most relevant parameters. Among them are the effective energies E12mm and E5MPa. Other factors, such as the stone volume and density also influence treatment outcomes. Using the voltage applied to the capacitors of the shock wave generator as the main adjustment parameter, an approach that dates back to the use of the first electrohydraulic lithotripters, fortunately has fallen out of practice.

For both ESWT and ESWL, the following parameters, provided by the equipment manufacturer, should be reported: peak positive pressure (p+), peak negative pressure (p-), rise time (tr), pulse full width at half maximum (tFWHM), energy flux density of the positive pulse (EFD+) and energy flux density of the complete wave (EFD).

The pressures p+ and p- refer to the peak amplitudes of the positive and negative pulses recorded at the focus. These are values obtained in the laboratory following specific standards and should not be interpreted as the pressures to which tissues are exposed during therapy. The values of tr and tFWHM are defined as the time required for the pressure to increase from 10 to 90% of p+ and the time from the instant when the pressure exceeds 50% of p+ for the first time, to the instant when the pressure drops again to this value, respectively. The EFD is the energy transmitted per unit area per pulse. It can be calculated either for the positive pulse alone or for both the positive and negative pulses. Even if it does correlate with mechanotransduction, its importance has been overstated.

The most important measurement parameters for ESWL are defined in the International Standard IEC 61846:2025. Its new edition, published in January 2025, updates and expands the original definitions for ESWL, adapting them to current use in ESWT, including orthopedic, cardiac, neurological, and soft tissue applications.

Recently, Wess and Mayer proposed that the transfer of momentum from a shock wave, that is, the physical process by which force is generated when the wave interacts with different tissue interfaces, is one of the most influential factors in clinical applications. Its effects span a wide range, from kidney stone fragmentation to mechanotransduction and even transcranial pulse stimulation (TPS) to improve Alzheimer’s complaints.

When reporting studies done with radial pressure sources, the impulse or impact (J) at the skin is a useful parameter to compare equipment; however, it should not be interpreted as a measure of biological response. It is expressed in newton-seconds (Ns) and defined as the integral of force over time. In simple terms, impulse measures how much force is applied to an object and for how long. The stronger the force and the longer it acts, the greater the impulse. It is calculated by adding up the total effect of the varying force over the duration of its application.

The IEC 63045:2020 standard establishes a uniform framework for measuring and evaluating the acoustic parameters of therapeutic devices that generate pressure pulses, including ballistic generators. It does not cover devices for ESWL. Specific requirements for ESWT were also published by the Technical Working Group of the German Society for Shock Wave Lithotripsy.

On the other hand, there have been published reliable guidelines that address clinical applications in areas such as musculoskeletal, bone, soft tissue, and urological disorders (excluding lithotripsy), providing information on how to measure and apply parameters based on scientific evidence.

Common errors in extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy

GENERAL ASPECTS

ESWL is considered as the first-line treatment for urinary stones smaller than 20 mm, being both safe and effective. However, outcomes differ markedly between lithotripsy centers, with success rates influenced by operator experience and clinical protocols.

Efficiency coefficients have been defined and can serve as a general guide. However, they should not be used on their own to compare the performance of lithotripters, since they also reflect factors such as the characteristics of the treated stone, patient selection criteria, and the skills of the medical team.

In ESWL, the learning curve to optimize the treatment according to the available equipment and the specifics of each case is relatively long. Training must be carried out by an experienced urologist. It is concerning that ESWL is often regarded as a non-challenging routine procedure and delegated to inexperienced urologists after receiving only superficial training, resulting in poor outcomes.

Routine is another factor that can reduce the efficiency of stone fragmentation during ESWL. It is often overlooked that poor outcomes are not necessarily due to the device or the potential of ESWL itself, but rather to poor practices that operators may develop over time. One common example is the failure to maintain close attention to the procedure after the patient has been positioned.

Parameters such as the shock wave rate are often based on custom rather than tailored to the specific clinical case. Most ESWL devices can deliver over 200 shock waves per minute. To shorten treatment times and increase the number of patients treated each day, some lithotripsy centers routinely apply high shock wave rates. However, this approach is not advisable. There is strong evidence showing that higher frequencies lead to increased cavitation, which in turn reduces the effectiveness of the treatment.

Lack of knowledge regarding the focal zone, the EFD, and other characteristics of the lithotripter, as well as the absence of a fluid-filled “expansion chamber” around the stone, significantly reduce the stone-free rate.

PATIENT POSITIONING

Excellent results can be achieved with most extracorporeal lithotripters, provided the devices are properly configured and patients are carefully selected and positioned. Even minor errors in patient alignment can greatly reduce treatment efficacy. Such misalignments often stem from insufficient understanding of how the lithotripter and its imaging system work. Furthermore, patient positioning should be verified several times during treatment. Most devices are equipped with advanced ultrasound and/or fluoroscopy systems. However, some configurations are more sensitive to operator training than others.

Transferring treatment protocols and patient positioning methods from one lithotripter model to another without carefully analyzing the technical details can significantly reduce fragmentation efficiency and may even cause tissue damage.

During ESWL, insufficient attention is often paid to small air pockets or bony structures that may lie in the path of the shock waves. These may appear during treatment due to slight patient movements. For this reason, proper use of imaging systems is essential. Fluoroscopy allows visualization of stones along the entire ureter, except for those that are very small. Whenever possible, ultrasound is recommended before and during treatment, as it can help identify both radiopaque and radiolucent stones.

Fragmentation efficiency drops significantly when the stone shifts perpendicular to the axis of symmetry of the shock wave source, especially if the focal zone of the lithotripter is small. Because the focal zone is ellipsoidal, misalignment along the axial direction is generally less critical. Situations like this highlight the importance of not switching lithotripters without a thorough understanding of the differences in pressure fields and imaging system performance compared to the previously used device.

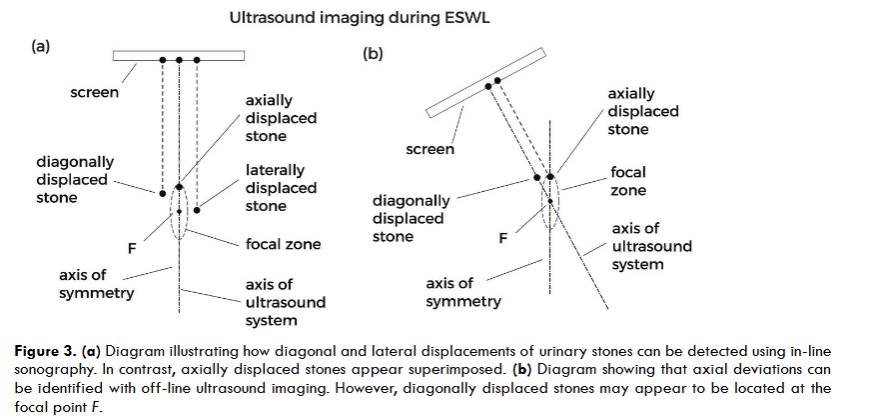

In-line ultrasound scanners are well suited for detecting proximal and distal ureteral stones located in the path of the shock waves. For lithotripters with a small focal zone, real-time coaxial ultrasound is an excellent tool. In these cases, the axis of symmetry of the shock wave generator aligns with that of the ultrasound system, making it easy to detect lateral and diagonal deviations of the stones. Axial deviations cannot be corrected using in-line systems, but if the error is small, the stone may still lie within the focal zone. These deviations can be identified using off-line ultrasound imaging; however, it is important to keep in mind that diagonally displaced stones may appear as if they were at the focal point. Detecting diagonal deviations may require imaging from two different projection angles. Regardless, as previously mentioned, small positioning errors can occur because shock waves and ultrasound do not follow exactly the same path through tissue.

Failure to recognize artifacts caused by the coupling interface is a mistake that can negatively impact treatment outcomes. A well-trained physician can use in-line ultrasound systems to detect air bubbles between the generator membrane and the patient’s skin.

Because the patient’s breathing causes the stone to move in and out of the focal zone, depending on the type of lithotripter used, a varying number of shock waves may fail to reach the target. Positioning the patient so that the stone aligns with the focus during exhalation may improve treatment outcomes by minimizing the number of pulses delivered while the stone is outside the focal zone. Nevertheless, in most cases, continuous shock wave triggering is preferred and seems tolerable even if a certain number of pulses are missing the stone.

SHOCK WAVE COUPLING

Despite decades of experience with ESWL, it is surprising that the incidence of basic errors has increased. One of the most common is inadequate coupling of shock waves to the patient. Air trapped between the generator membrane and the patient’s skin is often overlooked, even though it can significantly reduce energy transmission. Small air bubbles in the coupling medium, especially in ultrasound gels, can cause considerable attenuation. Using a suitable gel or castor oil is essential. Equally problematic are situations where the contact area between the generator membrane and the patient is too small to allow the full pressure cone to pass through, leading to energy loss.

This type of error becomes even more apparent when devices equipped with two confocal shock wave generators are not used correctly. Proper coupling of both generators requires thorough training. Delivering shock waves from two angles, whether in single-pulse, tandem, or simultaneous mode, offers potential for improved clinical outcomes. However, when operated by inexperienced users, these systems often perform well below their capabilities.

PROCEDURES

While it may not be considered an outright error, failing to take advantage of a clinical scenario where an expansion chamber could be created, allowing part of the stone to remain in contact with fluid, is an oversight that can impact the overall outcome of the treatment.

In ESWL, many common mistakes arise from treating the procedure as routine. Relying on fixed protocols that use high energy levels and a predetermined number of shock waves can lead to overtreatment rather than improved outcomes. As mentioned above, high shock wave emission rates should also be avoided, as they raise the risk of tissue damage. Furthermore, when comparing treatment protocols, terms such as dose, power, voltage, and intensity should be used with caution, since different lithotripters may generate distinct pressure profiles even when operating under similar settings.

VOLTAGE STEPPING

The consequences of increasing the voltage during ESWL depend on the type of lithotripter. Intuitively, one might assume that increasing voltage results in a linear growth in pressure; however, this is not the case. Nor should it be directly associated with greater treatment efficiency. In electrohydraulic systems, for example, the pressure response tends to level off above approximately 20 kV, meaning that further increases in voltage yield only marginal pressure gains.

There is evidence suggesting that starting ESWL treatments with a relatively low voltage and gradually increasing it is a good practice, except in the case of very hard stones such as cystine and calcium oxalate monohydrate. In those situations, it may be more effective to first induce fissures that can fill with fluid, allowing cavitation to take place. Once that has been achieved, lowering the voltage again is recommended.

Common errors in extracorporeal pressure wave therapy

SHOCK WAVES VS RADIAL PRESSURE WAVES

Radial pressure wave sources have been classified as devices that can be used by certified physiotherapists and licensed nursing personnel, once a physician has established the diagnosis and prescription. This can lead to the mistaken conclusion that such devices are harmless. Even if shock waves have the potential to cause much more harm than radial pressure waves, as mentioned earlier, ballistic generators emit rarefaction pulses with characteristics suitable for inducing acoustic cavitation. Improper use can cause tissue damage, which is why completing a certification course should be a mandatory requirement, not only for physicians, but also physical therapists and veterinarians.

RADIAL PRESSURE WAVE COUPLING

Just as with ESWL and ESWT, proper coupling is essential when using radial pressure waves. If the applicator is not pressed firmly against the patient’s skin, small air gaps may form, preventing effective wave transmission. This issue is particularly relevant when using concave applicators. Tilting the handpiece or moving it too quickly can also lead to the formation of gaps between the applicator and the skin, reducing treatment efficiency.

EQUIPMENT ADJUSTMENTS AND PARAMETERS

A wide range of ballistic devices is currently available on the market, many of which generate significantly different pressure fields. Several do not comply with international standards, and their manufacturers often fail to provide the minimum data required for proper evaluation and comparison with other systems. Clinical protocols based solely on the number of pulses, air pressure, and pulse repetition rate should not be published, as pressure profiles may vary considerably, potentially leading to significant differences in clinical outcomes. Moreover, changing the pulse rate alters the resulting pressure field.

A common misconception when using pneumatic ballistic devices is to assume a linear relationship between the air pressure set on the compressor (in bar) and the pressure of the emitted compression pulse (in MPa). While increasing the air pressure does lead to a stronger radial pressure wave, the relationship is not necessarily linear. The extent of this increase depends on the specific device. Still, regardless of the model, since not only the positive pressure peak but also the amplitude of the negative pulse rises with higher air pressure, more cavitation can be expected at elevated settings.

A common mistake is to assume that ballistic devices generate comparable pressure fields when operated at the same input air pressure. This holds true only for devices of the same model from the same manufacturer. In many clinical studies published in specialized journals, the only parameters reported are air pressure and pulse rate. Occasionally, the device model and manufacturer are mentioned, which may help retrieve missing technical information. However, readers should not be expected to undertake that task, even if they are aware of the issue.

It should also be noted that significant discrepancies can arise, as the measurement methods used by manufacturers often differ from those reported in the scientific literature.

Conclusions

One major obstacle to comparing results, designing reproducible protocols, and avoiding errors in both ESWL and EPWT is the lack of uniformity in device settings. Manufacturers have implemented different adjustment parameters, such as voltage, intensity, energy level, and pressure, which vary from one system to another. These parameters are device-dependent, so comparisons are only valid when made between systems of the same brand and model.

The definition of different focal zones further complicates the situation. To address this, energy flux density (EFD) was proposed, not only as a common reference parameter but as the key parameter for ESWT. However, no parameter has been found to correlate uniquely and directly with the physical or biological effects of interest. The situation has become even more challenging due to the rapidly increasing diversity of clinical applications.

The reported EFD is derived from the pressure-time graph at the focal point and should not be assumed to represent the entire pressure field.

The recently proposed concept of momentum transfer appears to be a promising approach for gaining a deeper understanding of the physical mechanisms of shock waves in medicine.

In EPWT, beyond the confusion regarding the pressure fields generated by different devices and the frequent misuse of terminology, there is a need for more rigorous training of physicians and therapists. Completing a certification course endorsed by a recognized professional society, along with regularly consulting reliable sources to stay informed and to use accurate terminology, is essential for achieving optimal clinical outcomes and minimizing the risk of patient injury. This applies both to ESWT and RSWT. It is equally important to ensure that the equipment in use complies with international standards and that the manufacturer provides the technical specifications required by the ISMST and the IFSWT.

Given the wide range of clinical applications for shock waves and radial pressure waves, it is essential to avoid generalizations, as each application involves distinct biophysical mechanisms. In most cases, the biological effects depend on factors such as the characteristics of the pressure field, energy density, focal region size, specific clinical indication, and the treatment protocol. It is also important to clearly define the criteria used to evaluate clinical outcomes and determine to what extent these outcomes can be attributed to the device and protocol used.

Conflicts of interest: The author declares that he has no conflicts of interest.

Funding N/A

Acknowledgments The author gratefully acknowledges the technical support of Guillermo Vázquez, and the valuable contributions and thorough review of the manuscript by Daniel Moya and Francisco Fernández.

References

- Chaussy C, Tailly G, Forssmann B, et al. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy in a nutshell. 2nd ed. Munich: Dornier MedTech Europe GmbH; 2014.

- Duarsa GW, Tirtayasa PM, Duarsa GW, Pribadi F. The efficacy and safety of several types of ESWL lithotripters on patient with kidney stone below 2 cm: a meta-analysis and literature review. Teikyo Med J. 2022;45:5613-5624.

- Alić J, Heljić J, Hadžiosmanović O, et al. The efficiency of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) in the treatment of distal ureteral stones: an unjustly forgotten option? Cureus. 2022;14(9):e28671. doi:10.7759/cureus.28671

- Sani A, Beheshti R, Khalichi R, et al. Urolithiasis management: an umbrella review on the efficacy and safety of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) versus the ureteroscopic approach. Urologia. 2025;92(2):294-311. doi:10.1177/03915603241313162

- Patel N, Stephenson-Smith B, Roberts J, Kothari A. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy: prematurely falling out of favour? A 7-year retrospective study from an Australian high-volume centre. BJUI Compass. 2023;5(4):460-465. doi:10.1002/bco2.314

- Rassweiler J, Henkel T, Köhrmann K, Potempa D, Jünemann K, Alken P. Lithotripter technology. Present and future. J Endourol. 1992;6:1-13. doi:10.1089/end.1992.6.1

- Ueberle F. Application of shock waves and pressure pulses in medicine. In: Kramme R, Hoffmann KP, Pozos RS, eds. Springer Handbook of Medical Technology. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2011:641-675. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-74658-4_33

- Loske AM. Medical and Biomedical Applications of Shock Waves. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2017. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-47570-7_1

- Oliveira B, Teixeira B, Magalhães M, Vinagre N, Fraga A, Cavadas V. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy: retrospective study on possible predictors of treatment success and revisiting the role of non-contrast-enhanced computer tomography in kidney and ureteral stone disease. Urolithiasis. 2024;52(65). doi:10.1007/s00240-024-01570-7

- Rola P, Wlodarczak A, Barycki M, Doroszko A. Use of the shock wave therapy in basic research and clinical applications – from bench to bedside. Biomedicines. 2022;10(568):10030568. doi:10.3390/biomedicines10030568

- Moya D, Ramón S, Schaden W, Wang CJ, Guiloff L, Cheng JH. The role of extracorporeal shockwave treatment in musculoskeletal disorders. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100:251-263. doi:10.2106/JBJS.17.00661

- Auersperg V, Trieb K. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy: an update. EFORT Open Rev. 2020;5:584-592. doi:10.1302/2058-5241.5.190067

- Tenforde AS, Borgstrom HE, DeLuca S, et al. Best practices for extracorporeal shockwave therapy in musculoskeletal medicine: clinical application and training consideration. PM R. 2022;14(5):611-619. doi:10.1002/pmrj.12790

- Császár NB, Schmitz C. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy in musculoskeletal disorders. J Orthop Surg Res. 2013;8:22. doi:10.1186/1749-799X-8-22

- Natornicola A, Moretti B. The biological effects of extracorporeal shock wave therapy (eswt) on tendon tissue. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2012;2(1):33-37.

- Wess O. Physics and technology of shock wave and pressure wave therapy. ISMST Newsletter. 2006;2(1):2-12.

- Cleveland RO, McAteer JA. Physics of shock wave lithotripsy. In: Smith AD, Badlani GH, Preminger GM, Kavoussi LR, eds. Smith’s Textbook of Endourology. 3rd ed. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012:529-558. doi:10.1002/9781444345148.ch49

- Cleveland RO, Chitnis PV, McClure SR. Acoustic field of a ballistic shock wave therapy device. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2007;33(8):1327-1335. doi:10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.02.014

- Ueberle F, Rad AJ. Ballistic pain therapy devices: measurement of pressure pulse parameters. Biomed Tech (Berl). 2012;57(Suppl 1). doi:10.1515/bmt-2012-4439

- Wess O, Mayer J. The interaction of shock waves with biological tissue – momentum transfer, the key for tissue stimulation and fragmentation. Int J Surg. 2025;111(4):2810-2818. doi:10.1097/JS9.0000000000002261

- Pishchalnikov YA, Neucks JS, Von der Haar RJ, Pishchalnikova IV, Williams JC Jr, McAteer JA. Air pockets trapped during routine coupling in dry head lithotripsy can significantly reduce the delivery of shock wave energy. J Urol. 2006;176(6 Pt 1):2706-2710. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2006.07.149

- Zhong P, Cioanta I, Cocks FH, Preminger GM. Inertial cavitation and associated acoustic emission produced during electrohydraulic shock wave lithotripsy. J Acoust Soc Am. 1997;101(5 Pt 1):2940-2940. doi:10.1121/1.418522

- Wan M, Feng Y, ter Haar G, eds. Cavitation in Biomedicine: Principles and Techniques. Heidelberg, New York, London: Springer; 2015. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-7255-6

- Delacrétaz G, Rink K, Pittomvils G, Lafaut JP, Vandeursen H, Boving R. Importance of the implosion of ESWL-induced cavitation bubbles. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1995;21(1):97-103. doi:10.1016/0301-5629(94)00091-3

- Bailey MR, Pishchalnikov YA, Sapozhnikov OA, et al. Cavitation detection during shock wave lithotripsy. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2005;31(9):1245-1256. doi:10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2005.02.017

- Philipp A, Delius M, Scheffczyk C, Vogel A, Lauterborn W. Interaction of lithotripter generated shock waves with air bubbles. J Acoust Soc Am. 1993;93(5):2496-2509. doi:10.1121/1.406853

- Bailey MR, Pishchalnikov YA, Sapozhnikov OA, et al. Cavitation detection during shock wave lithotripsy. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2005;31(9):1245-1256. doi:10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2005.02.017

- Lauterborn W, Ohl CD. The peculiar dynamics of cavitation bubbles. Appl Sci Res. 1998;58(1):63-76. doi:10.1023/A:1000759029871

“`