Mystery of Dreaming: Exploring Three Types of Dreams

MYSTERY OF DREAMING: THREE KINDS OF DREAMS

Anton Coenen

Donders Centre for Cognition, Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

[email protected]

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 August 2025

CITATION Coenen, A., 2025. MYSTERY OF DREAMING: THREE KINDS OF DREAMS. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(8). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i8.6757

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i8.6757

ISSN: 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Dreaming has fascinated mankind since antiquity. In most Christian cultures people believe that dreams bring messages of supernatural beings such as gods, angels and demons to the sleeper. Dreams contain often hidden messages, warning the sleeper for danger, predicting the future, clarifying situations, or rewarding or punishing the sleeping person. Many religious people assume that Gods preach through dreams. In contrast with sleep, where science reveals that sleep is crucial for physical health and many other functions, dreaming is still a mysterious process what difficult is to examine by science. There are several theories, but almost nobody can explain what a function of a dream is. The science of sleep starts toward the end of 1900 by a study of a certain Mary Cálkins, who found that in most dreams people told her, daily life is reflected. She formulated the continuity hypothesis who later was shifted by Rosalind Cartwright in the direction of the role of dreams to the regulation of emotions. The continuity hypotheses was perfected by Calvin Hall and Robert Van de castle. Good old Freud looked deeper and formulated the psychoanalytic theory implying that the psychoses of sick patients were perhaps coming from his adolescent period, which became a popular theory. It was in 1953 that Aserinsky and Kleitman discovered a second type of sleep, the REM sleep having many vivid dreams. Based on the brain activation by REM sleep Allan Hobson and Robert McCarley described the activation-synthesis hypothesis. Next to the dreams of normal sleep and REM sleep, the third type of dreams appear n hypnagogic hallucinations. It is recently demonstrated that dreams in hypnagogic hallucinations can indeed have creative qualities.

Keywords

Dreaming, REM sleep, hypnagogic hallucinations, continuity hypothesis, psychoanalytic theory

Introduction: early dream research

The scientific investigation of dreams began toward the end of 1880 by the study of Mary Cálkins (1863-1930)

. She was the first woman who passed all the requirements for a PhD at Harvard with distinction, and wrote her dissertation on memory, for which she developed the paired-associate experimental paradigm. Soon in 1887 she moved as an instructor of psychology and philosophy to Wellesley College and besides her lecture work and love for memory, she started at 1893 numerous recall analyses of dreams and confirmed the impression that most dreams were collected in the latest part of the night, and that the dream corresponds with current life activities. This is the continuity hypothesis of dreaming suggesting that dreams are the reflections of waking life. She was the first to conduct the first formal, empirical study of dream content, exploring the relationship between dreams and consciousness. At the end of the 19th century Mary Calkins and her female students made pioneering advancements in the psychological science of dreams (Calkins, 1893; Weed et al, 1896).

Dreaming: The Regulator of Emotions

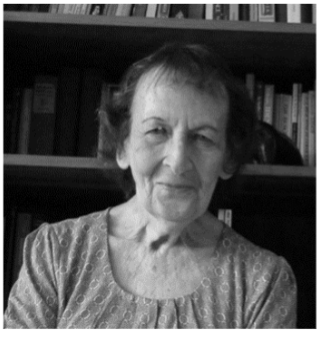

Rosalind Cartwright was a neuroscientist and professor emerita in the Department of Psychology and in the Neuroscience Division of the Graduate College of Rush University. Although sleep and dream expert of the Queen of Dreams (Cartwright s nickname) was interested in Freud s ideas in Die Traumdeutung, she did not accept that analyzing dreams us brought back to the unconsciousness of the mind. She believed that dreams simply reflect events that are important to the dreamer. A particular fascinating aspect of her research deals with dreaming as a mechanism for regulating negative emotions as well as the relationship between REM sleep, just discovered, and depressions. The more severe the depression, the earlier the first REM sleep begins. Sometimes REM sleep starts as early as 45 minutes into sleep. The first REM sleep period not only begins too early in the night in people who are clinically depressed, it lasts also often abnormally long. But what has perplexed researchers is that when the depressed patients are awakened 5 minutes into the first REM sleep episode, they are unable to explain what they have experienced. The conclusion of the Queen of Dreams was that dreaming served an important role and effectively down-regulated negative moods by matching disturbed daytime experiences with earlier memories. (Cartwright 1920).

The theory of Rosalind Cartwright (Fig. 1b) (1922-2021) was initially the continuity hypothesis as formulated by Mary Calkins, but soon she came to the view that dreams played an important role in the regulations of emotions (Cartwright 1977; Cartwright 1978). They down regulated in an effective way the negative mood by matching disturbing daytime experiences with earlier memories. This leads to their fusion and thus facilitating the integration of the disturbing experiences into positive memories.

Dreaming: The Continuous Hypothesis

The precursor of the continuity hypothesis of Mary Calkins was perfected by Calvin Hall (1909-1985) and Robert Van de Castle (1927-2014) (1966). This hypothesis implies that in most dreams daily life is reflected. Parts of waking life is still silently dominating in dream research although the precise functions of this theory remains unclear. Nevertheless, several psychologists confirm this interesting suggestion and it is a pity that the research was ended before further details of this view could be revealed. The most extensive and objective dream recall investigations were performed by the psychologists Hall

and Van de Castle

. They have studied and analyzed the content of thousands of dreams and developed a scale for scoring with an objective character. The categories they distinguished were mainly persons, social interactions, activities, good and bad luck, happiness and accidents, aggression and friendships and several elements. The results were just as those of Cálkins and Cartwright far from shocking. A dream is an reflection of waking life. Just as Cálkins and Cartwright, and Hall and Van de Castle she concluded that dreams have a normal content. People dream about daily life, about jobs, relations, hobbies, families and children. Dreaming consciousness is a representation of waking consciousness. This is the continuity hypothesis of the dream. Despite the many agreements there are relevant differences between the two forms of consciousness. We are not surprised about the absent of critical consciousness in the dream, and not about impossible events and the intertwining of scenes who stand apart in daily life. It is unfortunate that the continuity hypothesis came almost to an end with Hall and Van de Castle, while there were so many equal and unequal happenings and events in daily life and dreams. Given the relevance of the continuity hypothesis for dream science it is puzzling that the work related to this hypothesis ended and is not more cited in contemporary literature. Calkins pioneering work contradicted the Freudian view of dreams, leading her to feel embarrassed decades later about her findings, while also Cartwright was not impressed by Freud s work.

Dreaming of Patients: The psychoanalytical theory

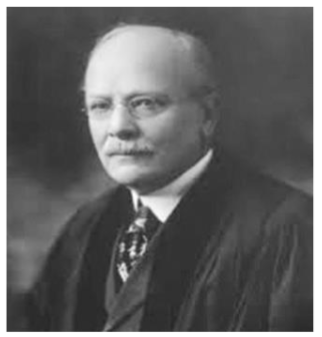

A significant advance in the interpretation of dreams occurred in the 19th century with the Austrian psychiatrist Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), who extensively studied dream theories and dream interpretations. He discovered in his practice in Vienna that many of his patients suffered from symptoms with no physical causes. He examined these patients with what he called free association and noticed that what the patients told him were mostly sexual and aggressive memories from their adolescent period (Freud,1912). Freud began to see an indisputable analogy between dreams and insanity. He integrated these elements in his psychodynamic writings on dreams, which he laid down in his impressive work Die Traumdeutung (The Interpretation of Dreams), which was published in 1900. Based on the dream recall of several of his psychiatric patients, he came to the conclusion that dreams are expressions of profound desires and fears, often related to repressed childhood memories and obsessions (Sullaway, 1983). The content of the dream was driven by the fulfillment of deep, often inappropriate, unconscious wishes. According to Freud, the unconscious continues to influence our behaviors and experiences, even though the awareness of the underlying influences. In the view of Freud, the dream forms an access to the unconscious mind: dreams are the royal road to the unconscious!

Dreams have both a manifest and a latent content. The manifest content is that what a dreamer later can recall of a dream, often bizarre and meaningless stories, while the latent content includes the real meaning, related to unconscious wishes or fantasies. It is the aim to extract the latent content from the manifest content, by careful analyzing the dream, bringing the unconscious into the consciousness. To understand the dream, the psychotherapist has to explore the latent content of the dream by the process of free association. The dreamer tells free and in a relaxed way to a trusted psychotherapist, what is in his mind. By spontaneous utterances and associations the therapist tries to understand what is in the unconscious mind of the dreamer. A basic idea is that in this familiar situation the repression is reduced and the unconscious can easier come into consciousness. This forms the basis of psychoanalysis, and many versions of this therapy are still in use, although the scientific basis is regularly under discussion. Mostly criticized is that the method of the free association might allow a relative random interpretation by the psychoanalyst, colored with his own visions and ideas. Despite the uncertainties of the analysis the psychoanalytical dream theory is still one of the most popular dream therapies.

Two types of sleep: non-REM sleep and REM sleep

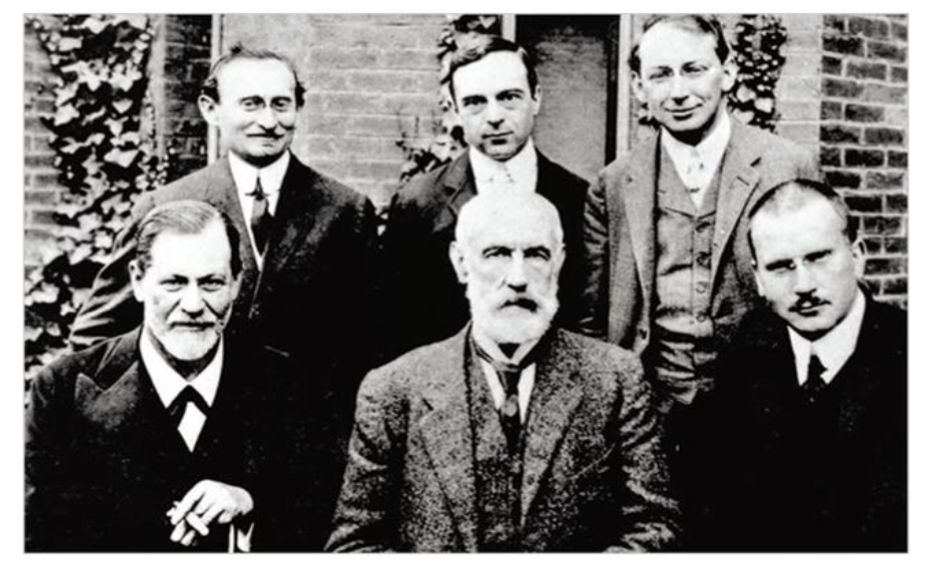

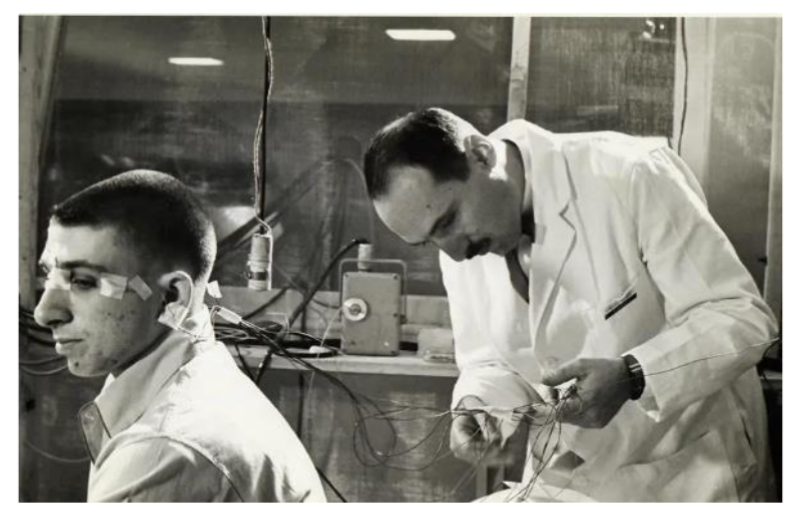

In a paper which appeared in 1953, the author, the American physicist Frank Ramsey, complained that so few documented studies are dedicated to dreaming, while mankind always had been interested in this phenomenon. The lack of scientific attention arising from the improbable analysis of dream reports has led to many speculative views. In that year, 1953, started Eugene Aserinsky in the laboratory of Dr. Nathaniel Kleitman, a professor in Physiology at the University of Chicago with sleep research. Kleitman from Jewish-Russian origin born in 1895 in Kishinev (Chişināu) the capital of Moldova), emigrated in 1915 to New York (USA) and received a professorship at the University of Chicago. Kleitman got two graduated students Eugene Aserinsky (1921-1998) and William (Bill) Dement (1928-2020). In that time Kleitman was particularly interested in the slow rolling eye movements accompanying sleep onset, and he decided to look for these eye movements whether they were related to the depth or quality of sleep. He suggested to Aserinsky to study these eye movements during sleep, but since Aserinsky was not so happy with this relative dull task, he began to look to the eye movements during the sleep of his son.

In order to measure accurately these eye movements, Aserinsky used an old polygraph which he found in the basement of the lab. He scrubbed the skin around the eyes of his son and taped electrodes to eyes and head, leading the wires to the printer in an adjacent room. Night after night he was recording eye movements and brain activity and after a while it attracted him that he sometimes saw large jerky eye movements swinging back and forth. This suggesting him that Armond was wide awake, but his eyes were closed and the boy looked asleep, while the brain activity was relative quiet. In further studies it was striking that a sort of rhythmicity between periods of slow and active eye movements appeared. Aserinsky got excited: Am I near the threshold of a great discovery, or is it perhaps an artefact caused by problems with the old polygraph machine?

After some extra experiments he was resolute in informing his boss Kleitman, although their relationship was not very well, knowing that the sleep specialist strongly believed in the passive nature of sleep (Kleitman, 1939). With conflicting feelings, he knocked on the door of the great Kleitman. The professor was suspicious listening to Aserinsky s story about the rapid eye movements (as he had termed the large jerky movements), but to his surprise Kleitman ordered immediately that he liked to see these movements during the sleep of his daughter Esther. When she also showed these large rapid eye movements, Kleitman realized soon that they were indeed on the trail of a great invention. In 1953 appeared their famous article under de dull title Regularly occurring periods of eye motility, and concomitant phenomena during sleep in the leading scientific magazine Science. It is one of the most cited papers in the history of sleep research, in particular since the authors loosely remarked that this type of sleep phase could be associated with dreaming.

The discovery of REM sleep is generally ascribed to the authors of the Science paper from 1953: Aserinsky and Kleitman. But serious controversies came up when a Russian article in 1926 titled Periodic Phenomena in the Sleep of Children appeared. It was written by the Russian couple Maria Denisova and Nicolai Figurin, both investigators of the Institute of Brain Research at Leningrad. When it appeared, however, that Denisova and Figurin investigated breathing in sleeping infants, which appeared concomitantly with rapid and unstable breathing, it became clear that the appearance of eye movements was not the focus of their study, implying that the credit for the discovery of REM sleep remained to the student and the professor of the Chicago team. The finding of REM sleep in 1953 was a great year in sleep research! The simple concept of the homogenous character of the sleep was over, because sleep is not a uniform state but consists of two different entities, perhaps with two different functions! It was the hope that a new paradigm to study dreaming was born!

Different dreams in the two types of sleep

The interest of the second graduate student of Kleitman, Bill Dement, to the study of the rapid eye movements during sleep, was strongly increased by the remark of Aserinsky and Kleitman that REM sleep could be associated with dreaming. Dement immediately thought that this type of sleep could bring him to the pathway of dreaming. Viewing all kinds of physiological phenomena, such as the activated EEG, similar to the waking pattern, the active sleep movements of the eyes during a specific sleep phase, the irregular breathing and heartbeat during this phase, and the relaxed muscles with twitches, did Dement realize that the rapid eye movements belonged to a different type of sleep, which he termed the Rapid Eye Movement sleep (REM sleep). He noticed that this is a completely different phase from the normal sleep, which he (strange enough) called the non-rapid eye movement sleep (non-REM sleep). Dement was convinced that REM sleep was the sleep that dreaming occurred. Sleep is thus not a uniform state but consists of different entities, perhaps serving different functions.

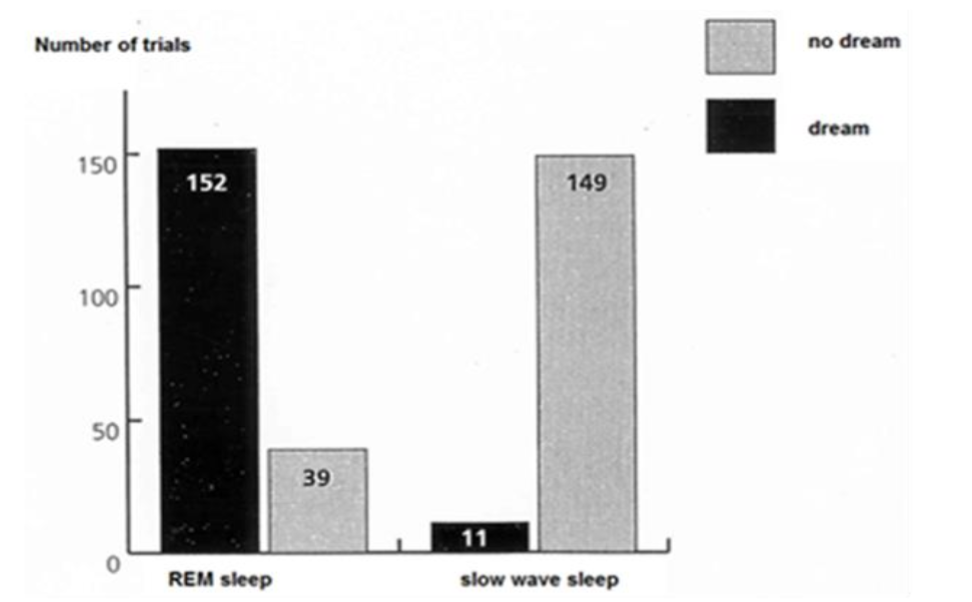

It was striking that he in his sleep lectures for students, the REM sleep already designated as the dreaming sleep. Indeed the physiological features of REM sleep with the mental features of a dream fit together on a wonderful manner. Should the dream research finally have got a new paradigm by the REM sleep? The Chicago team under the chairmanship of Dement and Kleitman used directly the REM recall technique to see whether an awakening from REM sleep always produced a dream recall, while that after an awakening from non-REM sleep this not take place always. When the relationship between REM sleep and dreaming is a one to one relationship, a high association between the two phenomena exists. Countless experiments of many researchers were done with the REM recall technique and this delivered results that were not completely identical. Mostly the recall from REM sleep was high, but the recall from non-REM sleep was mostly quite low and highly variable. Especially the differences in the non-REM recall was variable because the definition of a dream was not precisely enough formulated and while the subjects were awakened they could not indicate clearly what was going through their minds. Was it a dream or was it not a dream? This was often the situation in the non-REM recall episodes and less in the REM recall periods.

Gene Orlinsky, a graduate student of Allan Rechtschaffen, a prominent member of the Chicago group, developed an eight-point scale for the judgements of dream reports. The scale ran from 0 till 8, based on remembrance from zero, no dream at all, till a long dream story with many parts (8). The outcome of the Orlinsky experiment was that the recall in the 400 non-REM sleep recall responses were highly sensitive to the criteria used in the definition for ream recall (1,2 and 3). The lower the criteria for a dream the higher were the number of dreams. David Foulkes, a supporter for a precise definition of any report of men got right (Foulkes, 1962), and not the coherent but fairly vague detailed description of Dement and Kleitman. The idea of Dement and Kleitman that REM sleep only occurred with dreaming and that non-REM during sleep was never accompanied by dreaming was not correct! REM sleep and dreaming were not completely two sides of the same coin and non-REM sleep could sometimes be accompanied by dreaming. Two significant facts emerged from this result. REM sleep cannot longer be considered exclusively synonymous with dreaming, and dreaming could occur in the non-REM sleep (Coenen, 2003). In spite of the thematic continuity of the dreams of REM sleep and non-REM sleep, the investigation showed that non-REM mentation is generally more poorly recalled, more like thinking, and less like dreaming, less vivid, less emotional, and more pleasant.

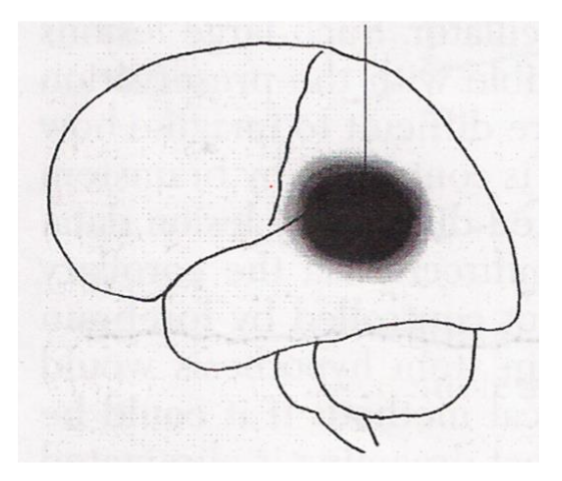

Nevertheless, a non-REM awakening will occasionally elicit a report that cannot be differentiated from a good REM report. These results confound completely the REM sleep is dreaming perspective, with the fixed relationship between REM sleep and dreaming. On the average, however, a decent difference remain to exist between the recall from REM sleep and from non-REM sleep. Neurological findings suggest that cholinergic brain stem mechanisms produce REM sleep, and that dreaming is controlled by forebrain dopaminergic mechanisms. From the pioneering work of the French researcher Michel Jouvet in 1962 it is already known that REM sleep is controlled by cholinergic pontine brain stem mechanisms. The REM generator stands therefore outside the dream process itself, although there is evidence that this mechanism might trigger the forebrain dreaming mechanisms. This means that the forebrain mechanism that generate dreams is relative independent of the pontine mechanism that generate REM sleep. The independency of the two mechanisms seems not completely, since recent findings suggest that cholinergic brain stem mechanisms controlling the REM state, can sometimes trigger the psychological phenomena of dreaming through the mediation of a probably forebrain mechanism. Indeed the fact that REM sleep and dreaming are often associated with a high physical and mental brain activity points towards the relative independency of the two phenomena.

Numerous studies suggest that dreaming involves a concerted activity of a specific group of forebrain structures. These structures include anterior and lateral hypothalamic areas, an amygdaloid complex, septal ventral striatal areas and several cortical areas. Primary visual cortex and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex are deactivated during REM dreaming (Solms, 1997). These findings suggest that the forebrain mechanism is the final common path to dreaming. Dreaming can be activated by a variety of dopaminergic forebrain pathways, and can be mediated by an independent non REM forebrain dream- mechanism, perhaps triggered by non-REM sleep.

If the assumption is correct that REM sleep is controlled by brainstem mechanisms, it must be possible to demonstrate by adequate lesions that REM sleep can be blocked. Indeed large lesions of the pontine brainstem eliminate all manifestations of REM sleep in cats (Jones, 1979). This correlation has been confirmed in twenty six human cases with naturally occurring lesions. When paid attention to the preservation of dreaming, Solms (1997) reported more than hundred published cases in the human neurological literature in which focal cerebral lesions are caused cessation or near cessation of dreaming.

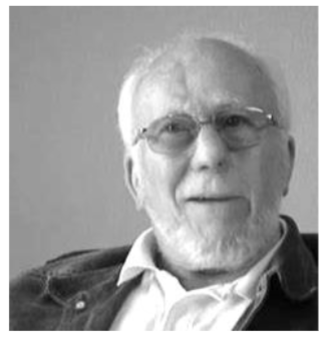

Dreaming: the Activation-Synthesis Hypothesis

Originally proposed by Harvard neuroscientists Allan Hobson and Robert McCarley (Fig. 6) was that dreaming resulted in the attempts of the brain to make sense of the high neural activity during REM sleep. They call this the activation-synthesis hypothesis (Hobson and McCarley, 1988). The neuroscientists knew that circuits in the brainstem are activated, leading to REM sleep. The produced activity ascends by PGO waves to higher brain areas involved in sensations, emotions and memories, while the cortex synthesizes these internal processes together with external information into a story to create a meaning. This results in dreaming images and since the brain has difficulties to produce an acceptable story of all signals, this leads to chaotic scenes, objects and stories, forming an often surreal, illogical, emotional and bizarre narrative. This is curiously enough experienced by the dreamer as a reality. This implies that the dream itself is a byproduct of the activity produced by REM sleep, initially originating in the brainstem and spreading to higher cortical areas. In this view REM sleep must have an important, still unknown function, while the dream might eventually be an unintentional, perhaps senseless byproduct.

Here the main contrast between the psychoanalytical theory with the focus on the dream content and the activation-synthesis theory with the focus on the physical electrical signals is seen. In this view, the direct psychoanalytical dream theory founded by Sigmund Freud may obtain to some degree a scientific basis. Thus even when the dream is a genuine epiphenomenon of REM sleep, without any function or meaning, it can eventually contain relevant information since useful memory traces are activated. Indeed the content of the recalled dream, consists frequently of memory images with a mix of remote and recent memory traces. In the psychoanalytical dream theory, a certain interpretation of a dream content seems often possible, although the dream interpretation is often regarded as speculative, having a limited scientific basis. The question now is whether a reliable interpretation of the manifest dream content is possible. Perhaps, when the insight in the unconscious mind is growing, the methodology of bringing the unconscious to consciousness will get a more solid scientific basis. A mysterious feature of the incorporation of external stimuli into REM sleep dreams is that the experience of stimuli during dreaming phases are more different than during waking. The mind in sleep can show his mysterious kind of consciousness (Hobson and McCarley, 1977), which might be related to how external stimuli are reconstructed within the brain, in terms of emotional tone, stimulus modality, or story plot, so that the reconstructed stimuli better fit into an ongoing dream scenario (Solomonova and Carr, 2019).

Dreaming in Hypnagogic Hallucinations

Dreaming can take outside REM sleep. A dream can emerge in non-REM sleep, when the fluctuating brain activity is highly enough, and further at sleep onset in so called hypnagogic hallucinations and upon awakening in hypnopompic hallucinations. A common feature of these states is associated with a degree of consciousness of REM sleep or a REM sleep-like state, almost reaching from sleep to waking consciousness, or from wake to sleeping consciousness. Especially in hypnagogic hallucinations it occurs that external stimuli are incorporated into a REM sleep dream.

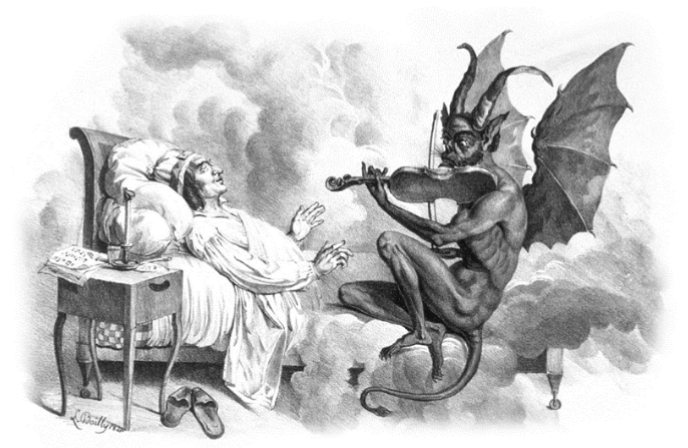

The Italian composer and violinist Giuseppe Tartini (1692-1770) was dreaming that he had a problem in playing a sonata, which he has composed. In his dream he handed the devil his violin to test the devil s musical skills, and the devil played the song with exceptional virtuosity! Tartini tried to recollect the music afterwards and played based on the beautiful devil s music the sonata so nice that he called this composition The Devil s Thrill Sonata.

Hypnagogic hallucinations are vivid, often frightening dreams that occur at sleep onset or offset. Most people have experienced these visual, tactile or auditory images that occur at the transition from waking to sleep or reverse. Sometimes these perceptions are accompanied by sleep paralysis or by an intense muscle shock. Feelings of falling into a hole, or flying, can also be experienced in these hallucinations. Hypnagogic hallucinations can also occur when they take place upon awakening, so called hypnopompic hallucinations. Hypnagogic hallucinations are called dreamlike, for the reason that they occur at the transition from waking to sleep. In hypnagogic hallucinations the EEG pattern is active looking like REM sleep, and the dreams are similar to those in REM sleep. This underlines the view that REM sleep and dreaming are relative separate processes to hypnagogic hallucinations and their dreams. In narcoleptic patients, suffering from the intrusion of REM sleep when they are awake, similar hallucinatory phenomena occur (Barrett, 2017). During a narcoleptic attack, frightening and dreamlike hallucinations can emerge, associated with sleep paralysis and cataplexy. All in all integration of external stimuli into a hypnagogic hallucination in the twilight zone takes place where wake transits into sleep.

Creative dreaming in Hypnagogic Hallucinations

One of the first who attracted attention that dreams or dreamlike events could have creative features was American scientist Charles M. Child who in 1892 at a young age calculated that from the 200 male and females subjects about 30% of them answered with yes on the question that they could rapidly solve a difficult problem during sleep, or even could directly notice the solution directly after awakening. Unfortunately, the eventual creative possibilities of dreamlike happenings have been totally ignored by later scientific investigators. In Figure 8 is given a creative hallucination, where another well-known example of a hypnagogic hallucination with creativity comes from the chemist Friedrich Kekulé in 1890. He was studying the molecular structure of benzene and in an intimate report, he noted I was deeply thinking about the structure of benzene, I turned my chair to the fire and dozed. The atoms were gamboling before my eyes. Smaller groups kept modestly in the background, and my mental eye, could distinguish larger structures of conformation; long rows sometimes fitted together all twining and twisting in a snake-like motion. But look! A snake had seized hold of its own tail, and the ring-form whirled mockingly before my eyes. As by a flash of lightning I awoke, and I spent the rest of the night in working out the consequences of the hypothesis: the ring structure of benzene! The creative moment in the hallucination, which gave rise to the wake-up call, took place in the time during the transformation of the stimulus by the mind into a dreaming hallucination. Hypnagogic hallucinations are often linked to creativity, in the sense that these dreams can aid creativity and problem-solving behavior (Barrett, 2017).

Next to the creative hypnagogic hallucinations in the past, such as the well-known hallucinations of Tartini with the Devils Thrill, and Kekulé with the ring structure of benzene, many others are described such as the frog heart experiment of Otto Loewi with the chemical transmission of nerve impulses, the dream of Hermann Hilprecht with a priest telling him the true translation of the stone of Nebuchadnezzar. the artist Charles Child in 1892 and later William Dement (1972) mentioned already that the creative and problem solving-behavior of dreams have been ignored completely by scientific investigators.

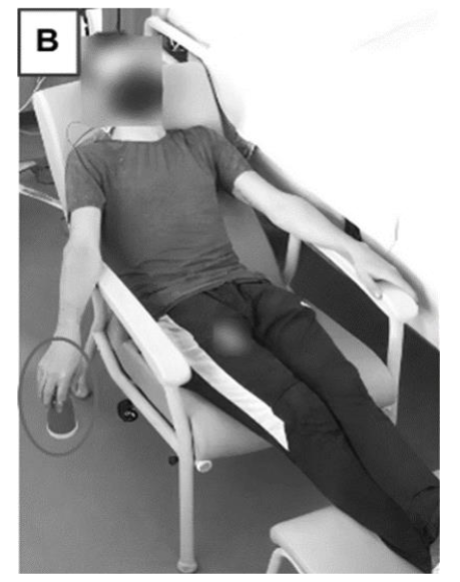

Recently, Lacaux et al (2019) found that patients with narcolepsy displaying high levels of hypnagogic hallucinations obtained high scores in tests for creativity, with an increase in original thinking. In a recent experiment (Fig. 9.) Lacaux et al (2021) exposed participants to mathematical problems without the knowledge that a hidden rule could solve these problems easily and almost instantaneously. They found that spending a short time in the twilight zone tripled their changes of discovering the hidden rule. This finding suggests the existence of a creative sweet spot at sleep onset, when a realistic external event changed the hallucinatory story, perhaps associated with creative insights. The incorporation of an external narrative into a dream story may be associated with creative solution-solving behavior. A burning question arises what would happen if this experiment by Lacaux et al (2021) could be performed during the naturally occurring REM sleep? Could there also be a creative or problem-solving period during REM sleep? This might be an eye on the function of the mysterious REM sleep, which most people do believe that it has an unknown function, and others that it has no function at all. And what about dreams of the common non-REM sleep? It is even more interesting whether these dreams contain any creativity!

Discussion and Conclusion

The first hypothesis in the literature about dreaming was the continuous hypothesis around 1900. Early psychologists recalled what happened in the dream and what kind of persons, events and happenings, together with the kinds of tools and instruments occurred in dreams. Scientists agreed that dreams were the reflections of all day life. It was a pity that this simple although interesting hypothesis was overshadowed by more interesting hypotheses. The research of Mary Cálkins and Rosalind Cartwright delivered more or less the same, although Cartwright was also interested in the relation between REM sleep emotions and depression. The continuous hypothesis was perfected by Calvin Hall and Robert Van de Castle. But it was a pity that their work related to the hypothesis almost came to an end when more interesting hypotheses came up and the interesting continuous hypothesis was not cited in contemporary literature.

The psychoanalytic hypothesis of Sigmund Freud, came up in the 19th century and got a lot of attention. Freud had many patients with psychosis for which he could not find a physical cause. He examined these patients and analyzed them with what he called free association. He suggested that the beginning of the psychosis was started in the adolescent period of the patient by dreams which were mostly sexual and inappropriate. He learned to understand the dream and was able to prescribe an adequate therapy for this late childhood psychosis expressed on a relative old age. And despite the fact that the therapy was often not so successful, the psychoanalytical theory with many versions and despite the uncertainties of the dream analysis, was presently the most popular dream theories for several kinds of psychoses.

In 1953 student Aserinsky together working with Nathaniel Kleitman did a major scientific discovery. They described a new type of sleep which they called the rapid eye movement sleep (REM sleep) named to the large eye movements during this type of sleep. It was another member of the group of Kleitman, William Dement, who suggested that REM sleep was the sleep for dreaming. In 1957 Dement and Kleitman published the results and found a high dream recall for REM sleep and the low dream recall for the non-REM periods. They regarded that as a proof of their suggestion, although the low non-REM recall was curious. Many recall experiments followed and when the fact that now and then but consistently non-REM sleeping subjects reported only few dreams upon awakening, came an important disappointment in dream research for many dream researchers. It confounded the fixed relationship between sleeping and dreaming. However, on the average a difference existed between recall from REM sleep and from non-REM sleep, there is a difference in REM sleep and in non-REM sleep mentation. The most important notion. From the literature it emerged that the general assumption that REM sleep is the equivalent of dreaming needs a thorough revision. REM sleep and dreaming are not identical processes and REM sleep has to be divorced from dreaming. REM sleep and dreaming are dissociable states. It was a shock (positive or negative) for the entire sleep world.

The principle that dreaming only occurs during REM sleep and that dreaming does not occur in the absence of REM sleep is no longer disputed. The REM sleep is dreaming perspective, originally introduced by Dement and Kleitman (1957), from which dreaming was viewed as a characteristic exclusive to REM sleep was ended by Foulkes s observation (1962) that dreaming mentation can be found in more than 50% of non-REM awakenings. But the notion that REM sleep and dreaming are highly connected is still present in most societies and REM sleep is still often called the dreaming sleep. But it non-REM sleep and REM sleep are two states with own control mechanisms and features and with own dreams. The original enthusiasm around the discovery of REM sleep has now two sides: it has delivered new, interesting questions concerning the function of the mysterious REM sleep phenomenon, but it has not brought us more insight into the nature of dreams, the most intriguing experiences in life.

References

Cálkins, MW (1893) Statistics of dreams. American Journal of Psychology, 5(3): 311 343. !893

Weed, SC, Hallam, FM, Phinney, ED and Cálkins, MW: Minor studies from the psychological laboratory of Wellesley College: III. A study of the dream-consciousness. American Journal of Psychology, 7(3): 405 411.1896

Cartwright, RD: Night Life: Explorations in Dreaming. Englewood Cliffs, Prentice-Hall. 1977

Cartwright, RD: A Primer on Sleep and Dreaming. Addison-Wesley series in clinical and professional psychology. Reading: Addison-Wesley Pub, 1978

Cartwright, RD: The Twenty-Four Hour Mind: The Role of Sleep and Dreaming in our Emotional Lives. Oxford: Oxford University, 2010

Hall, CS and Van de Castle, RL: The Content Analysis of Dreams, Century psychology series, New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1966

Sulloway, F.J.: Freud: Biologist of the mind. New York: Basic Books, 1983

Freud S.: Types of Onset of Neurosis, Standard Edition, 12: 229-238, 1912

Kleitman, N.: Sleep and Wakefulness, Midway Reprint Chicago. The University of Chicago Press, 1939, 1987

Aserinsky, E., Kleitman, N.: Regularly occurring eye motility, and concomitant phenomena, during sleep. Science, 118: 273-274, 1953

Dement, W.: Some must watch while some must sleep. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Company, 1972

Dement, W:., Kleitman, N.: The Relation of Eye Movements during Sleep to Dream Activity: An Objective Method for the Study of Dreaming. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 53(3): 339-346, 1957

Orlinsky, G., Psychodynamic and cognitive correlates of dream recall, A study of individual differences. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Chicago, 1962

Foulkes, D.: Dream reports from different stages of sleep. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 65: 14-25, 1962

Foulkes, D: Dream research: 1953-1993. Sleep 19(8): 609 624, 1996

Denisova, K. Periodic phenomena in the sleep of children. Journal Novoe v refleksologii I fiziologii nervnoi sistemy, 2: 338-345 Written by Maria Denisova and Nicholai Figurin, English Translation, 1926

Jouvet, M.: Recherches sur les structures nerveuses et les mécanismes responsables des differences phases du sommeil physiologique. Archives Italiennes de Biologie, 100: 125-206, 1962

Solms, M.: The neuropsychology of dreams: a clinic-anatomical study. Erlbaum, 1997

Solms, M.: Dreaming and REM sleep are controlled by different brain mechanisms. Sleep and Dreaming. Cambridge University Press, 51-58, 2003

Coenen, A.: The divorce of REM sleep and dreaming. Sleep and Dreaming. Cambridge University Press, 133-135, 2003

Coenen A: The Mystery of Dreaming and REM sleep. Jurnal Ilmiah Psikologi MANASA 9(1), 1-7, 2020

Nielsen, T.: A review of mentation in REM and NREM sleep: Covert REM sleep as a possible reconciliation of two opposing models. Cambridge University Press, 59-74, 2003

Jones, B.: Elimination of paradoxical sleep by lesions of the pontine gigantocellular tegmental field in the cat. Neuroscience Letters, 13: 285-293 1997

Hobson, J.A.: McCarley, R.W.: The brain as a dream state generator. The Dreaming Brain. Basic Books, Inc., New York: Scientific American Library, 1988

Hobson, J.: An activation-synthesis hypothesis of the dream process. American Journal of Psychiatry 134: 1335-1368, 1977

Solomonova, E., Carr, M: Incorporation of external stimuli into dream content. in Dreams: Understanding Biology, Psychology, and Culture. Eds. Dreams: Hoss, R, Valli, K., and Gongloff. Greenwood, Publishing Group, 2019

Barrett, D. Dreams and creative problem-solving. Annals New York Academy of Sciences, 1406 (1); 64-67, 2017

Lacaux, C., Andrillon, T., Bastoul, C., Idir, Y., Fonteix-Galet, A., Arnulf, I., Oudiette, D.: Sleep onset is a creative sweet spot. Science Advances 7(50), 2021

D’Anselmo, A., Sergio, S,. Filardi, M., Fabio., P., Mastria., S., Corazza., G., Plazzi., G.: Creativity in Narcolepsy Type 1: The Role of Dissociated REM Sleep Manifestations. Nat Sci Sleep 17(12): 1191-1200, 2020

Lacaux., C., Izabelle., C., G Santantonio., G., De Villèle., L., Frain., J., Lubart., T., Pizza., F., G Plazzi., G., Arnulf., I., Oudiette., G.: Increased creative thinking in narcolepsy. Brain 142(7): 1988-1999, 2019

Hyman, L. N. Charles Manning Child, 1869 1954. Biographical Memoirs, vol. 30. New York, 1957.