Nebulization Optimization for Obstructive Airway Disorders

Nebulization Optimization for Management of Obstructive Airway Disorders: An Expert Review (NOVA-ER)

Raja Dhar (MD)1, Ansuman Mukhopadhyay (MD)2, Devasahayam J Christopher (DNB)3, Deepak Talwar (DM)4, Gopi C Khilnani (MD)5, Indranil Halder (MD)6, Joydeep Ganguly (MD)7, Parvaiz A Koul (MD)8, Prashant Chhajed (MD)9, Vikram Jaggi (MD)10, Vinit Niranjane (MD)11

- Raja Dhar, MD Department of Pulmonology, Calcutta Medical Research Institute, Kolkata, West Bengal, India

- Ansuman Mukhopadhyay, MD Consultant, Advanced Medicare Research Institute Hospital AMRI Hospital, Kolkata, West Bengal, India

- D. J. Christopher, MD Department of Pulmonary Medicine, The Christian Medical College and Hospital, Vellore, Tamil Nadu, India

- Deepak Talwar, DM Department of Pulmonology, Metro Center for Respiratory Diseases, Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India

- Gopi C. Khilnani, MD Department of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, PSRI Hospital, New Delhi, India

- Indranil Halder, MD Department of Pulmonology, College of Medicine and JNM Hospital, Kalyani, Nadia, West Bengal, India

- Joydeep Ganguly, MD Department of Pulmonology, Chest Clinic, Berhampore, West Bengal, India

- Parvaiz A. Koul, MD Department of Internal and Pulmonary Medicine, Sher-i-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences, Srinagar, Kashmir, India

- Prashant Chhajed, MD Centre for Chest and Respiratory Diseases, Nanavati Max Super

- Vikram Jaggi, MD Vinit Niranjane, MD Department of Respiratory Medicine, Seth G S Medical College Wockhardt Hospital, Nagpur, Maharashtra, India

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 April 2025

CITATION: DHAR, Raja et al. Nebulization Optimization for Management of Obstructive Airway Disorders: An Expert Review (NOVA-ER). Medical Research Archives, [S.l.], v. 13, n. 4, apr. 2025. ISSN 2375-1924. Available at: <https://esmed.org/MRA/mra/article/view/6377>.

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i4.6377

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

Background: Nebulization therapy is an essential inhalation technique for managing obstructive airway diseases such as asthma, bronchiectasis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). In Indian clinical settings, factors such as diverse patient populations, varying disease severity, and healthcare accessibility influence treatment decisions. While clinicians rely on the only available nebulization guideline, its vastness and complexity pose challenges in practical application. Navigating these guidelines and translating recommendations into routine practice remains difficult.

Objective: The NOVA-ER manuscript aims to develop a structured, evidence-based, and expert-driven reference document to streamline nebulization practices in clinical settings and provide guidance for home nebulization.

Methods: A comprehensive review of peer-reviewed literature, clinical guidelines, and systematic reviews was conducted using databases such as PubMed, MEDLINE, and the Cochrane Library, with a focus on studies published in the last ten years to ensure relevance. Additionally, expert opinions were gathered through a structured panel discussion involving specialists in respiratory medicine. A predefined set of questions guided these discussions, and clinical feedback was incorporated to refine recommendations.

Key Takeaways: This manuscript presents stepwise algorithms tailored to individual obstructive airway diseases, facilitating decision-making for both rescue and maintenance therapy. It also helps identify suitable candidates and agents for home nebulization while providing disease-specific guidance for effective nebulization treatment. Furthermore, it integrates expert perspectives with current clinical evidence to optimize nebulization practices.

Conclusion: NOVA-ER is designed to serve as a practical tool for clinicians, researchers, and policymakers, offering structured guidance to enhance nebulization practices, support home nebulization, and bridge the gap between evidence-based guidelines and its practical applicability in clinical care, which may help improving patient outcomes.

Keywords: ACO, Asthma, Bronchiectasis, Bronchodilator, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, COPD, Nebulization

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), respiratory diseases are associated with significant morbidity and mortality, affecting over 500 million people worldwide. Risk factors such as aging population, urbanization, air pollution, biomass usage in developing countries, smoking, occupational exposures, genetics, and infections are strongly linked to increased prevalence of obstructive airway diseases like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma. The prevalence of COPD is 13% among individuals aged 40 years and older, making it the third leading cause of death and the seventh leading cause of disability worldwide. In India, COPD contributes to 3% of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) due to chronic respiratory diseases and is the second most common cause of mortality in India. The national burden of asthma has been estimated at 17.23 million, with an overall prevalence of 2.05%. India contributes to 42% of global asthma mortality. Comorbidities potentiate the burden of asthma and impact the mortality rates of both COPD (10-40%) and asthma (15-35%). Bronchiectasis frequently coexists with poorly controlled asthma and COPD, and its prevalence in India noted in a recent study was 7.1% (range between 5.9-20.5%). Overlap of bronchiectasis with other airway diseases is associated with increased lung inflammation, frequent exacerbations, declining lung function, and higher mortality. A single-center study with a small sample size conducted in North India reported that 17% of patients with COPD had bronchiectasis. Overlapping conditions like Asthma-COPD Overlap Syndrome (ACOS) cannot be ignored because this is linked to higher BMI, poorer lung function, and a greater risk of frequent and severe acute exacerbations, as well as a higher number of exacerbations per year compared to patients with “pure” COPD. In southern Rajasthan, 31.05% of bronchial asthma reportedly had Asthma-COPD Overlap (ACO) with a predominance in females and higher comorbidities. Conversely, a study in Thanjavur found that 25% of the study population exhibited features of Asthma-COPD overlap. Treatment options for these overlapping conditions include pharmacological interventions (such as the use of inhaled forms of bronchodilators, corticosteroids, antibiotics, and other anti-inflammatory agents), non-pharmacological approaches (like oxygen therapy and pulmonary rehabilitation), and surgery.

Given the rising burden of respiratory diseases, maximizing the utilization of existing medical resources becomes essential. However, there is a suboptimal use of nebulizers in the management of common respiratory diseases in India. To remedy this situation, this review aims to comprehensively examine current literature on the use of nebulization in the treatment of COPD, asthma, bronchiectasis, and overlapping obstructive or inflammatory respiratory diseases. It also provides structured, and evidence-based expert recommendations improving its clinical applicability in the treatment of the most prevalent chronic respiratory diseases in diverse patient populations in India.

PROBLEM STATEMENT

Inhalation therapy is the cornerstone of pharmacological treatment in patients with obstructive, inflammatory, and infectious respiratory diseases. However, it often fails to resolve the symptoms due to varied reasons such as poor adherence to therapy, low inspiratory flow, reduced dexterity due to multiple comorbidities, physical disability, age, injury, cognitive impairment, and errors in the use of inhalers. Other reasons include lack of awareness, lack of education, poor coordination, and physical inability to use handheld inhalers.

APPROACH TO LITERATURE REVIEW AND DEVELOPMENT OF EXPERT OPINION

We conducted a comprehensive search of peer-reviewed articles, clinical guidelines, and systematic reviews related to the use of nebulization in managing common respiratory diseases. Databases such as PubMed, MEDLINE, and Cochrane Library were extensively searched using keywords like “nebulization,” “respiratory diseases,” “clinical management,” and “inhalation therapy.” The selection criteria focused on studies published in the last ten years to ensure the inclusion of the most recent evidence. Studies not available in English or lacking clear methodology were excluded. Data from selected studies were extracted, analyzed, and synthesized to identify current practices and existing gaps. This review provided a foundational understanding of current practices, identified gaps in the literature, and supported the expert panel’s discussions by aligning their opinions with existing evidence.

To collate expert opinions on the use of nebulization in managing common respiratory diseases, we conducted a closed-group meeting of selected pulmonology experts with at least 10 years of clinical experience and extensive academic contributions to the field of respiratory medicine. A moderator prepared a structured list of pre-determined questions to guide the discussion. Each expert contributed clinically relevant insights, facilitating the formulation of expert opinions. Expert opinion was generated through consensus, while ensuring that the expert perspective aligned with the best available evidence, focusing on clinical applicability. This iterative process allowed the refinement of viewpoints through group feedback, resulting in a comprehensive document on nebulization therapy.

Inhalers and Errors

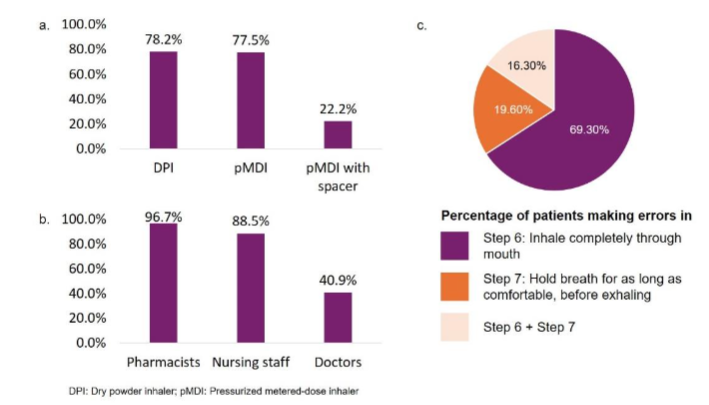

Considerable research suggests that incorrect use of inhalers is associated with poor clinical outcomes and impaired quality of life in patients with respiratory diseases. Studies revealed that 30-60% of patients with asthma and 80% of patients with COPD made at least one critical error while using inhalers. Moreover, 15% of trained healthcare professionals err while using inhalers, leading to suboptimal disease control and increased risk of exacerbations, hospitalizations, and death. As a result, recent publications have quantified error-prone steps to help reduce the frequency of persistent errors. Using dry powder inhalers (DPIs) and pressurized metered-dose inhalers (pMDIs) involves multiple steps that need to be carried out correctly to ensure optimal delivery of medication. For pMDIs specifically, nine critical steps must be followed to achieve optimal inhalation and therapeutic effectiveness. It has been observed that more than 70% of patients make errors in 3 key steps, namely: ‘Breathe in,’ ‘Sit straight,’ and ‘Hold breath.’ An observational cross-sectional study found that 75.36% of patients demonstrated errors in inhaler use, regardless of the device type. Error rates were 78.2% for DPIs, 77.8% for pMDIs, and 22.2% for pMDIs with spacers (Figure 1a). Notably, training by healthcare professionals did not uniformly reduce errors, with pharmacist-led training resulting in high error rates (Figure 1b). The most common errors involved incomplete inhalation through the mouth and inadequate breath-holding (Figure 1c). These findings highlight the critical need for more effective inhaler education.

Nebulization

For some patients, inhalation technique errors may be mitigated by using alternative devices, such as nebulizers, to help manage respiratory diseases in an effective manner. Many studies have demonstrated that nebulizers are as effective as inhalers, easy to use, have no complex hand-breath coordination required, and are suitable for most patients (including the elderly and those who are unable to use other inhalation devices) and when patients need a large dose of inhalation medication. However, inhalers remain the first choice of therapy in patients with chronic respiratory diseases. Therefore, it is imperative for physicians to select the most appropriate inhalation device and explain its correct use to optimize drug delivery among patients.

CHRONIC BRONCHITIS/ VIRAL BRONCHITIS

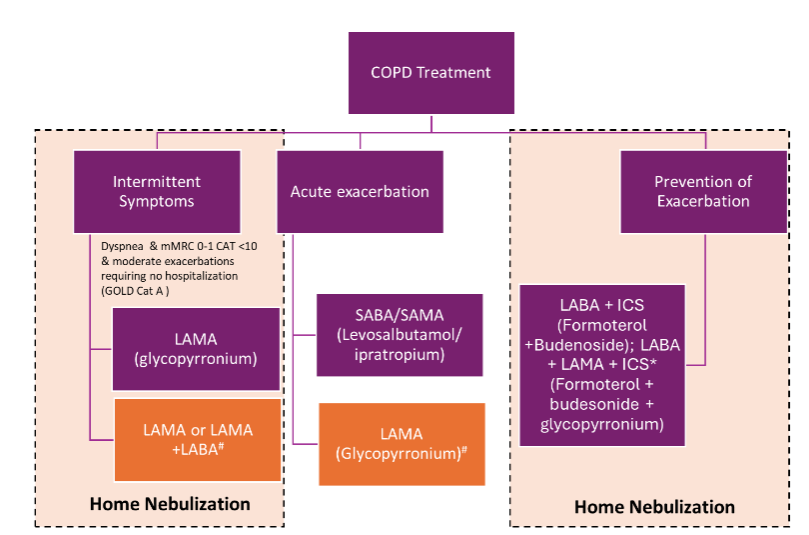

Chronic bronchitis may be diagnosed when a person experiences a cough with mucus for more than three months within a two-year period. Viruses are responsible for over 90 percent of acute bronchitis infections. Consequently, antibiotics are not indicated for bronchitis, except when pertussis is suspected to reduce transmission or if the patient is at increased risk of developing pneumonia, such as patients 65 years or older. Chronic bronchitis (CB) is a common condition in COPD that affects treatment outcomes and quality of life. Nebulized glycopyrrolate has shown significant improvements in lung function and health-related quality of life in COPD patients, regardless of CB status. However, evidence comparing nebulizers to other delivery methods for bronchodilators during COPD exacerbations is limited. A systematic review found no significant difference between nebulizers and pMDI with spacers on FEV1 or safety, although nebulizers showed greater improvement in FEV1 around to one hour after dosing. Intravenous N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) related bronchospasm can be treated with a nebulized bronchodilator. In the context of eosinophilic bronchitis, the effectiveness of corticosteroids can be inconsistent. The Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America (AAFA) notes that inhaled corticosteroids may not be effective for everyone with this asthma subtype. A cross-sectional study conducted in 2020 revealed that people who used inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) had raised blood eosinophil counts even after treatment, which could be due to poor compliance with the prescription or steroid resistance, which requires further investigations. Many studies are available on the use of formoterol and glycopyrronium in COPD, and the same have been tabulated in Table 1. According to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2023 report, bronchodilators can be used for Group A COPD patients (classification according to GOLD) who suffer from 0-1 exacerbations and Modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea Scale (mMRC) 0-1, CAT <10. These qualify as intermittent symptoms that do not need hospitalization. Glycopyrrolate, a long-acting anti-muscarinic agent, should be used for intermittent COPD symptoms not requiring hospitalization (Figure 2). CAT ≥ 10, should be treated with a combination of long-acting beta2 agonist (LABA) + long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA).

| Author | Drug | Type of Therapy | Study details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Donohue et al. | Nebulized Formoterol | Twice daily | Intermittent /maintenance. Improved pulmonary function. Peak FEV1, trough FEV1, and FVC (measures of lung function) increased and stayed better. The need for rescue medication was reduced by almost half. |

| Geffen et al. | SABA/SAMA Salbutamol/ Ipratropium (IPR) | Maintenance therapy | Aimed to find change in FEV1 curve from baseline till six h. The peak in FEV1 was higher and was reached faster with SAL/IPR compared to IND/GLY. |

| Berry RB et al. | Nebulized Albuterol | Reliever therapy | Albuterol improved the percent change in FEV1 at 1h post-treatment compared to MDI plus spacer (16.7% ± 17.0 vs 13.4% ± 20.5). |

| Yahong Chen et al. | Nebulized budesonide vs. Systemic corticosteroids | Reliever therapy | Nebulized vs. Systemic corticosteroids: Chinese AECOPD study assesses nebulized corticosteroids (NCS), systemic corticosteroids (SCS), and NCS+SCS effectiveness. NCS Consideration: NCS proves effective, but NCS+SCS is linked to longer stays and higher costs in certain patients, prompting further trials. |

| Hakan Gunen, et al. | Multidrug regimen comparison in all types of COPD patients | Reliever therapy | Approx 48% of patients were switched to LABA+LAMA+ICS to control exacerbations. |

| Vijay et al. | Nebulised budesonide/formoterol | Add on to Salbutamol/Ipratropium | Improvement in PEFR, relieved inflammation, scarring, bronchospasm, and mucus; thus, airflow through the bronchi and the degree of obstruction in the airways improved. |

TREATMENT OF ACUTE EXACERBATIONS/EMERGENCY NEBULIZATION

Exacerbators or newly defined GOLD Group E patients should be treated with short-acting β2 agonist (SABA) or short-acting muscarinic agonist SAMA (Figure 2), i.e., levosalbutamol or ipratropium. Levosalbutamol alone or in combination with ipratropium is extensively used for treating acute COPD exacerbations, as given in Table 1. Alternatively, a LAMA, glycopyrronium has also been used in treating exacerbations effectively, as given in Table 1.

MAINTENANCE THERAPY AND PREVENTION OF EXACERBATION IN CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE

Long-acting beta agonist / Long-acting anti-muscarinic (LABA/LAMA) in combination or as monotherapy has been extensively studied in many patients. A fixed combination of LABA + ICS (formoterol and budesonide) has been recommended in both exacerbations as well as maintenance of COPD. Triple therapy has been more effective in terms of lung function and symptom control, as well as reducing exacerbation when compared to dual combination, particularly for patients with an eosinophil level >300 cells/µL. The latest recommendations also support the use of triple therapy (LABA + LAMA + ICS) over dual therapy (LABA + ICS).

ASTHMA

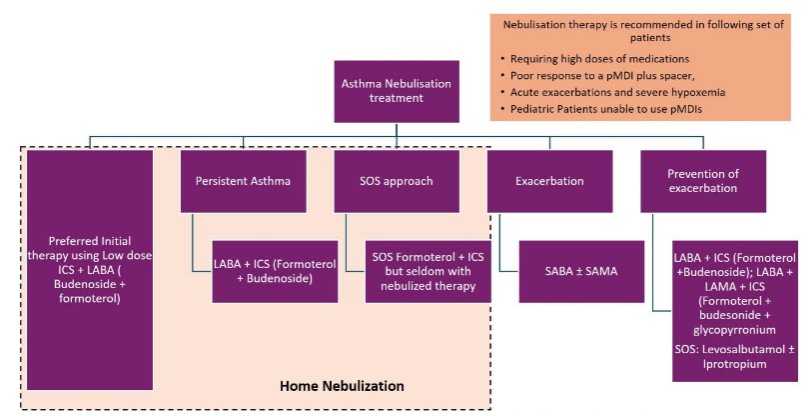

Airway inflammation is the hallmark of asthma, and inhaled steroids are the mainstay of treatment as they provide protection against bronchospasms induced by any stimuli. Nebulization is recommended in patients requiring high doses of medications, those with poor response to pMDIs plus spacer, acute exacerbations, severe hypoxemia, and pediatric patients who can’t use pMDIs (Table 2).

| Author | Drug | Respiratory condition | Study details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Talwar et al. | Nebulized formoterol/budesonide plus glycopyrronium | Difficult-to-treat asthma cases with frequent use of rescue medications | Nebulized formoterol/budesonide plus glycopyrronium add-on therapy significantly improved FEV1 at 8 weeks (P<0.001). Mean pre-bronchodilator FEV1 improved significantly (23.7%, 0.46 L; P<0.001). Post hoc analysis showed a significant 11.2% improvement in pre-bronchodilator FEV1. LAMA add-on therapy via nebulizer increased FEV1 by 27% in 8 weeks compared to baseline. |

| Kulalert et al. | Comparison of SABA Nebulization | Continuous maintenance and intermittent reliever therapy | The study evaluated the effectiveness of continuous and intermittent SABA nebulization as a first-line treatment for severe asthma in hospitalized children. Improved treatment success in continuous treatment vs intermittent nebulization. |

HOME NEBULIZATION AND PREFERRED INITIAL THERAPY

Many bronchodilators act as controller agents when given with ICS. The fixed combination of LABA and ICS is effective in improving asthma control and is the preferred controller agent for moderate to severe asthma. LABA, in combination with ICS like budesonide/formoterol, are extensively studied and widely accepted as first-line therapy for asthma. By optimal utilization of ICS and LABA therapy to prevent asthma exacerbations, the study suggests that using budesonide-formoterol combination as a reliever therapy may be more efficacious than conventional combination or salbutamol or terbutaline monotherapy. Studies have proven that nebulized budesonide and inhaled budesonide are equally effective. Nebulized budesonide may improve peak flow, symptoms of asthma, O2 saturation, β agonist effects, and reduce patient distress. Figure 3 serves as a useful tool to plan the nebulization drug delivery.

HOME NEBULIZATION IN RESCUE THERAPY AND PERSISTENT ASTHMA

The combination of ICS/LABA as reliever therapy significantly enhances asthma control and lowers the risk of severe exacerbations, making it effective for persistent asthma. Inhaled maintenance and reliever therapy is supported by strong evidence and is acknowledged by the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) as a single inhaler therapy. However, there is insufficient evidence regarding the efficacy of maintenance and reliever therapy delivered through nebulization; therefore, this approach can only be recommended when its utility is confirmed by further trials. For patients with severe, poorly controlled asthma, there is a clinical necessity to have a less complex nebulizer for home therapy to deliver both relievers and controllers using minimal inspiratory flow, especially for use at home or in ambulatory settings. Home nebulization with glycopyrronium add-on approach delivers a clinically significant bronchodilation duration, which may be of value in patients with difficult asthma with moderate to severe exacerbations and who are on corticosteroids.

EMERGENCY NEBULIZATION IN EXACERBATION AND HOME NEBULIZATION DURING DISCHARGE ADVICE

Exacerbation or episodes of asthma can be treated with a combination of SABA and SAMA. Patients hospitalized due to acute exacerbations can be safely discharged and managed with LABA + LAMA + ICS triple therapy. Rescue therapy: Levosalbutamol ± ipratropium, formoterol ± glycopyrronium / budesonide (refer Figure 3).

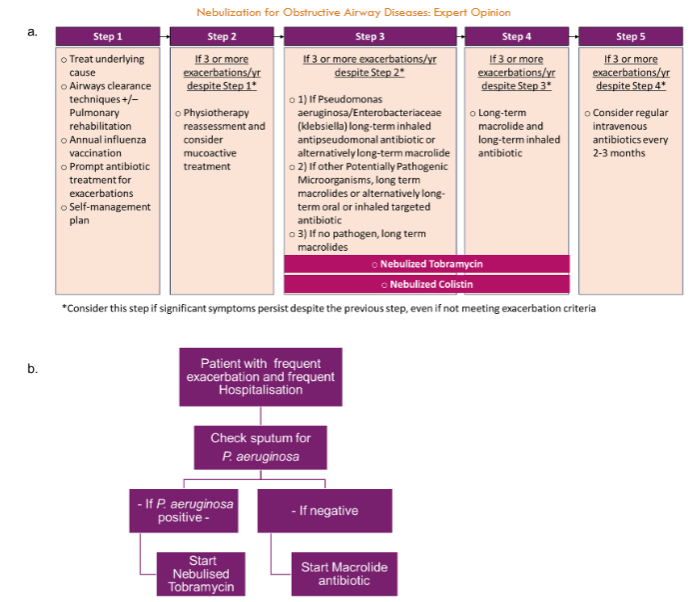

BRONCHIECTASIS

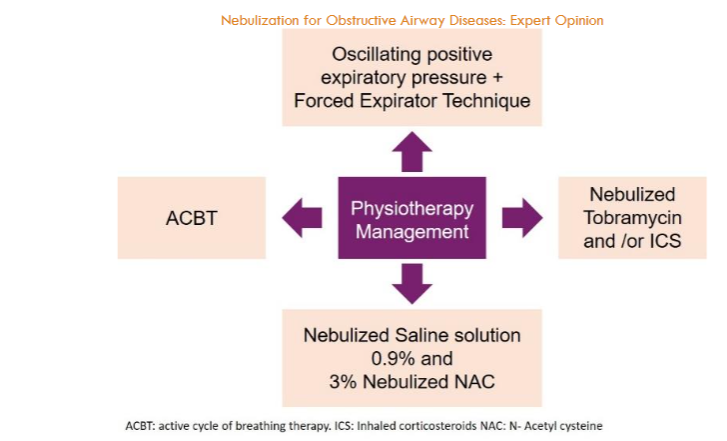

Bronchiectasis is characterized by irreversible dilation of bronchi, inflammation, infections, and exacerbations. Despite rising prevalence, there is limited research and no approved treatments for this chronic lung condition. Also, the European Multicenter Bronchiectasis Audit and Research Collaboration (EMBARC) India registry findings highlight suboptimal management of bronchiectasis. Therefore, stepwise management, as suggested by the British Thoracic Society (BTS), European Respiratory Society (ERS), and American Thoracic Society (ATS), will help clinicians manage the disease effectively. Around 60% of bronchiectasis patients were not prescribed airway clearance techniques; evidence-based treatments such as low-dose macrolides and inhaled antibiotics were used in <10% of cases. It is essential to treat the underlying cause of bronchiectasis and apply airway clearance techniques and/or pulmonary rehabilitation. Figure 4 highlights methods of airway clearance using nebulized saline (0.9%, 3 %, and 7%) and nebulized NAC.

NEBULIZED TOBRAMYCIN

Inhaled tobramycin has proven to be effective in decreasing sputum bacterial density in individuals with bronchiectasis and chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) infection. Furthermore, the use of inhaled tobramycin has been associated with a higher rate of P. aeruginosa eradication compared to placebo, as observed during a median follow-up period of 4.3 weeks. Orriols et al. (2015) conducted a study with a longer follow-up duration and reported a significantly longer time for P. aeruginosa recurrence in the tobramycin group (p = 0.048). Moreover, maintenance of clearance was observed in 54.5% of patients at 15 months. Importantly, at present, there is insufficient evidence to suggest that the use of inhaled tobramycin leads to the development of resistant strains of P. aeruginosa.

NEBULIZED COLISTIN

Studies on the use of colistin for Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) infections have shown varying outcomes. Tabernero et al. conducted a randomized clinical trial with 39 patients, administering nebulized colistin (1 million units) twice daily for a year, resulting in a reduction in hospitalization and PA eradicated in 45% of patients. Steinfort et al. studied 18 patients with bronchiectasis or COPD and found that six months of colistin (30 mg) via jet nebulizer led to a decline in FEV1 and improved quality of life. Dhar et al. reported a significant reduction in exacerbations and hospital admissions after six months of nebulized colomycin. Haworth’s study showed no difference in primary endpoints like time to first exacerbation. Safety issues with inhaled colistin included mild side effects in 0% to 40% of patients, such as cough, bronchospasm, and dyspnea. Dry-powder inhalers had higher side effect rates (54.2%), with cough being the most common (84%) and causing treatment discontinuation in 24.4% of patients. Risk factors for adverse effects included severe bronchiectasis, longer symptom duration, pre-existing cough, device handling difficulties, and lack of therapeutic education.

NEBULIZED SALINE SOLUTION

Nebulized hypertonic saline (HS) is commonly employed to assist mucociliary clearance in bronchiectasis. Mucoactive agents prescribed in patients with bronchiectasis include nebulized hypertonic saline (concentrations ranging from 3 to 10%) and isotonic saline (concentration of 0.9%).

NEBULIZED N-ACETYL CYSTEINE

In adult bronchiectasis patients with at least two exacerbations in the past year when prescribed NAC (600 mg twice daily), the incidence of exacerbations in the NAC group was significantly lower than that in the control group (1.31 vs. 1.98 exacerbations per patient-year risk ratio, 0.41; 95%-CI, 0.17-0.66; P = 0.0011). The long-term use of NAC can reduce the risk of exacerbations. In a study by Shehzad et al. NAC was compared with 3% hypertonic saline, and the results demonstrate that both agents offer a similar efficacy for airway clearance and increase in oxygen saturation in the patients experiencing severe bronchiectasis exacerbations.

ASTHMA-CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE OVERLAP SYNDROME (ACOS)

While airway obstruction is a common characteristic in both asthma and COPD, the overlap of these exhibits notable differences in clinical practice. There is an evident pathological and functional overlap between them, particularly among the elderly, referred to as ACOS. There is a lack of evidence-based literature to guide therapeutic decisions for patients with ACOS. Traditionally, these patients have been systematically excluded from clinical trials involving COPD and asthma treatments to maintain homogeneity in the study population. Differentiation of ACOS patients according to their phenotype has been suggested in the GINA 2022 report. This recommendation for the use of ICS stems from several studies demonstrating that patients diagnosed with both asthma and COPD face a greater risk of hospitalization or mortality when treated with LABA as opposed to ICS+LABA combination therapy. Ironically, some experts have proposed the ICS+LABA combination as a first-line therapy for ACOS. If an ACOS patient’s symptoms are inadequately controlled with an ICS + LABA combination, the addition of a LAMA should be considered, particularly when recurrent exacerbations occur. It is noteworthy that the GOLD 2020 update no longer refers to ACO but instead recommends using blood eosinophil counts to guide ICS therapy in COPD. ACO patients represent a unique group that may benefit from more targeted therapy, mirroring current practices in asthma and COPD management. Therefore, this subgroup of patients warrants careful identification for further mechanistic studies and individualized management. The selection of nebulized drugs should be as per the above evidence, while ICS continues to be the mainstay of treatment. The indication for the use of nebulized drugs over drugs administered by other inhaler devices will be based on indications mentioned in the asthma/COPD sections.

BRONCHIECTASIS AND CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE OVERLAP SYNDROME (BCOS)

Along with bronchodilators and mucolytics, patients with bronchiectasis are sometimes treated with long-term antibiotics such as macrolides and nebulized antibiotics. Hence, individuals presenting chronic cough, sputum, chronic bronchial infection, and frequent infective exacerbations are prescribed LABA/LAMA with macrolide antibiotic as an add-on therapy. The choice of inhaled drug for the treatment of BCOS would be the same as selecting a bronchodilator or an ICS for treating COPD alone. There is some evidence that the use of ICS in the Bronchiectasis-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap syndrome (BCOS) population may lead to an increase in the bacterial load. Hence, inhaled drugs should be used with great caution in the BCOS population as compared to the ‘COPD alone’ population. Till then, the evidence for the management of COPD and bronchiectasis (as single entities) is to be used for the overlap entity.

NEBULIZED THERAPIES IN CRITICALLY ILL PATIENTS / NEBULIZATION IN ASSISTED VENTILATION

Nebulization in assisted ventilation is crucial for delivering medications to patients with critical respiratory conditions who require mechanical ventilation. This method allows for the administration of a variety of medications; particularly, antibiotics and bronchodilators. In the case of antibiotics, the Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society guidelines for nosocomial pneumonia recommend adding inhaled antibiotics to systemic treatments for patients with gram-negative pneumonia caused by multidrug-resistant pathogens sensitive only to polymyxins and aminoglycosides. Inhaled colistin is specifically recommended over polymyxin B and can be considered a last resort for non-responding ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) patients, regardless of pathogen sensitivity. The use of aerosolized antibiotics offers the advantage of achieving high intra-pulmonary concentrations, which can be effective against highly resistant pathogens. Bronchodilators administered via nebulization also play a significant role in managing respiratory conditions in mechanically ventilated patients. Nebulizers can operate continuously using pressurized gas from a 50-psi wall outlet or gas cylinder, or they can be synchronized with the ventilator’s inspiratory flow. This synchronization significantly reduces aerosol losses during exhalation and enhances drug delivery efficiency by up to four times. The dose required for effective bronchodilation in ventilator-supported patients is similar to that used in spontaneously breathing patients, although the duration of the bronchodilator response is shorter in mechanically ventilated COPD patients. Therefore, scheduled administration of short-acting β-agonists like albuterol every 3-4 hours is necessary. For jet nebulizers, a fill volume of 4-5 mL is recommended to prolong treatment time and ensure proper medication dilution, maximizing the amount nebulized during mechanical ventilation. Nebulized bronchodilators improve overall lung ventilation by reducing aeration in non-dependent pulmonary regions, with no significant differences observed between various ventilation modes. Optimizing these nebulization practices and understanding their mechanisms can significantly enhance patient outcomes in respiratory care. The targeted delivery of high concentrations of medication directly to the lungs, combined with reduced systemic absorption, makes nebulization an effective and efficient method of treatment in mechanically ventilated patients.

IMPORTANCE AND BENEFITS OF DOMICILIARY NEBULIZATION/HOME NEBULIZATION

Inhalational medication is vital for managing chronic airway diseases. Recent studies suggest that nebulizers could enhance patient outcomes in special populations. Nebulized treatment is an effective alternative for patients with cognitive, neuromuscular, suboptimal peak inspiratory flow, and ventilatory impairments. It eliminates the requirements for optimal inspiratory flow, manual dexterity, and complex hand-breath coordination. Elderly patients, those with severe disease and frequent exacerbations, and those with physical and/or cognitive limitations should use nebulizers for maintenance therapy. For elderly patients and those with severe COPD and disabling dyspnea, delivering the total dose over several breaths with a nebulizer may be more effective than a single breath with a DPI or pMDI. Improvement in FEV1 was achieved in 75% of patients with the same combination of drugs when used with a nebulizer instead of the inhaler. Moreover, a 20% reduction in perceived level of breathlessness was reported with the use of nebulizers when compared to inhalers. Studies also showed significant improvements in symptoms and quality of life, with 60-75% of patients preferring the use of a nebulizer over an inhaler. There was a remarkable reduction in hospital readmission and exacerbations whilst using home nebulization, as evident by 30-day and 90-day readmission rates. Approximately 50% of patients experiencing residual symptoms after treatment with inhalers benefited from home nebulizer use.

Best practice statements regarding airway obstructive airway diseases and their management with Nebulization (Expert opinion)

- Inhalers should continue to be used as the first-line therapy, while nebulizers are essential for specific patient groups requiring easier administration or higher-dose medication.

- Nebulized LAMA like glycopyrrolate significantly enhances lung function and quality of life in COPD patients, offering consistent benefits regardless of chronic bronchitis status.

- Nebulizers are recommended in emergency settings for treating acute COPD exacerbations, especially with SABA or SAMA, either alone or in combination.

- For those with frequent exacerbations of COPD, triple therapy with LABA, LAMA, and ICS (e.g., formoterol, glycopyrronium, and budesonide) is strongly recommended, particularly for patients with high eosinophil counts.

- Nebulization is very important in asthma management, especially when a patient has severe symptoms, is not responsive to inhalers, has not responded well to metered dose inhalers, and requires a high dosage of the medication, including children.

- Home nebulization with budesonide is equally effective as budesonide via inhaler, improving peak flow, asthma symptoms, and patient comfort, therefore a valuable option for managing persistent asthma.

- For moderate to severe asthma, the combination of LABA and ICS, particularly formoterol/budesonide, is the preferred first-line treatment and is highly effective in both maintenance and reliever asthma therapy.

- Rescue therapy for patients admitted due to exacerbations of asthma may use fixed combinations such of SABA + SAMA i.e., levosalbutamol and ipratropium or LABA + LAMA / ICS formoterol and glycopyrronium or budesonide, supporting both emergency and home nebulization strategies.

- According to currently available guidelines on bronchiectasis, the stepwise management of bronchiectasis focuses first on airway clearance and pulmonary rehabilitation before using nebulized antibiotics, which is critical in the management of the condition.

- Nebulized antibiotics, including tobramycin and colistin, are encouraging in bronchiectasis with chronic P. aeruginosa infection, especially tobramycin, which can reduce the bacterial load and increase time to P. aeruginosa recurrence.

- Nebulized hypertonic saline (HS) and NAC are effective mucoactive agents that enhance mucociliary clearance and reduce exacerbations in patients with bronchiectasis, enhancing patient prognosis.

- Inhaled tobramycin and colistin show efficacy in the management of bronchiectasis; however, patient-specific factors such as disease severity and therapeutic education are critical to minimizing side effects and ensuring treatment adherence.

- Administration of long-term inhaled antibiotics and NAC has been found to decrease the frequency of exacerbations in bronchiectasis; therefore, it should be considered an essential component of bronchiectasis management.

- To manage ACOS (Asthma phenotype), the use of ICS+LABA combinations should be preferred since evidence suggests that LABA alone is less effective in reducing hospitalization and mortality.

- In Bronchiectasis-COPD overlap syndrome, inhaled corticosteroids should be used cautiously due to their potential to increase bacterial load, highlighting that further research needs to be conducted to establish the best approach to managing this overlap syndrome.

- In patients with both bronchiectasis and asthma, there should be a proper assessment for fungal pathogens, and management plans should include anti-fungal treatment if fungal infection is detected as well as oral steroids and long-term macrolide therapy for eradication of bacterial and fungal infection.

- Nebulization is necessary for providing bronchodilators and antibiotics for patients with critical illnesses, and mechanical ventilation with synchronization to ventilation providing better therapeutic effects.

- Nebulized antibiotics, such as colistin, are recommended as an essential strategy in the management of ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by multidrug-resistant gram-negative pathogens, achieving high intra-pulmonary concentrations effectively.

Box 1: Patient profiler for nebulization in asthma

- Over 40 years old, with chronic airflow obstruction (post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC < 0.70 or below the lower limit of normal).

- History of at least 10 pack-years of smoking.

- History of asthma before age 40 or a significant bronchodilator response (more than 400 mL increase in FEV1).

- Recurrent wheezing and shortness of breath, particularly noticeable with exertion (e.g., shortness of breath on climbing more than one flight of stairs).

- Positive family history of asthma (e.g., mother with asthma).

Table 3: List of all Nebulization Formulations Available in India

| Nebulizing solution/s | Category |

|---|---|

| Arformoterol, Formoterol | LABA |

| Budesonide | ICS |

| Fluticasone propionate | ICS |

| Formoterol + Budesonide | LABA+ICS |

| Glycopyrronium inhalation | LAMA |

| Ipratropium | SAMA |

| Levosalbutamol | SABA |

| Levosalbutamol and Budesonide | SABA + ICS |

Conclusion

Home nebulization represents an important aspect of respiratory care, garnering attention, and acceptance among Indian experts. It plays a crucial role in managing respiratory conditions such as asthma and COPD. The significance of nebulization lies not only in the effective drug delivery directly to the lungs but also in its versatility as both maintenance and rescue therapy. However, the successful implementation of home nebulization depends on several factors. Most importantly, selecting appropriate patients is paramount, as not everyone may benefit from nebulizer therapy. Experts, therefore, emphasize the importance of careful patient selection to maximize the benefits while minimizing potential risks. Furthermore, experts highlight the need for comprehensive patient education. Advising patients on appropriate maintenance, cleaning, and disinfection of nebulizers is essential to ensure device hygiene and optimal functionality. Also, patient counselling plays a key role in improving adherence to prescribed nebulizer treatment, thereby promoting long-term medication compliance to maintain positive health outcomes.

Conflicts of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge Dr. Jay Savai, Dr Kapil Dev Mehta and Ms. Nikita Lakkundi from JB Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Mumbai for the smooth conduct of the recommendation development process. We acknowledge Dr. Melissa Perriera from Royal Medical Services, Mumbai, for language editing services. We also acknowledge Dr. Mayuresh Garud from SciPrez, Pune, for providing manuscript editing and publication support.

References

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). WHO Newsroom: March 16, 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-(copd) Accessed August 9, 2024

- Jarhyan P, Hutchinson A, Khaw D, Prabhakaran D, Mohan S. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic bronchitis in eight countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2022;100(3):216-30. doi:10.2471/BLT.21.286870

- Singh S, Salvi S, Mangal DK, Singh M, Awasthi S, Mahesh PA, et al. Prevalence, time trends and treatment practices of asthma in India: The Global Asthma Network study. ERJ Open Res. 2022;8(2):00528-2021. doi:10.1183/23120541.00528-2021

- Yeo Y, Lee H, Ryu J, Chung SJ, Park TS, Park DW, et al. Additive effects of coexisting respiratory comorbidities on overall or respiratory mortality in patients with asthma: a national cohort study. Sci Rep. 2022;12:8105. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-12103-w

- Mekov E, Nuñez A, Sin DD, Ichinose M, Rhee CK, Maselli DJ, et al. Update on Asthma–COPD Overlap (ACO): A narrative review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2021;16:1783-99. doi:10.2147/COPD.S312560

- Martínez García MÁ, Soriano JB. Asthma, bronchiectasis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the Bermuda Triangle of the airways. Chin Med J. 2022;135(12):1390-3. doi:10.1097/CM9.0000000000002225

- Dhar R, Singh S, Talwar D, Mohan M, Tripathi SK, Swarnakar R, et al. Bronchiectasis in India: results from the European Multicentre Bronchiectasis Audit and Research Collaboration (EMBARC) and Respiratory Research Network of India Registry. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(9):e1269-79. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30327-4

- Sharma BB, Singh S, Sharma KK, Sharma AK, Suraj KP, Mahmood T, et al. Proportionate clinical burden of respiratory diseases in Indian outdoor services and its relationship with seasonal transitions and risk factors: The results of SWORD survey. Hadda V, editor. Plos One. 2022;17(8):e0268216. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0268216

- Wu Y, Zhang J. Standardized inhalation capability assessment: A key to optimal inhaler selection for inhalation therapy. J Transl Intern Med. 11(1):26-9. doi:10.2478/jtim-2022-0073

- Zhou XL, Zhao LY. Comparison of clinical features and outcomes for asthma-COPD overlap syndrome vs. COPD patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25(3):1495-510. doi:10.26355/eurrev_2021-02_24857

- Shukla D, Chhabra D, Kumar Sharma R, Luhadia D, Sharma D, Luhadia D, et al. Prevalence and demographical variation of asthma COPD overlap (ACO) in previously diagnosed chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients of Southern Rajasthan: A cross-sectional study. Int J Adv Res Med. 2021;3:523-5. doi:10.22271/27069567.2021.v3.i1i.195

- Akilandeswari SH, Kavitha B, Sudhakaran J, Rajkanth K. A study on “Prevalence of COPD overlap in asthma patients–hospital based cross sectional study.” Int J Sci Res. 2021;42-4. doi:10.36106/ijsr/1907079

- Alhaddad B, Smith FJ, Robertson T, Watman G, Taylor KMG. Patients’ practices and experiences of using nebuliser therapy in the management of COPD at home. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2015;2(1):e000076. doi:10.1136/bmjresp-2014-000076

- LaCrone ME, Buening N, Paul N. A retrospective review of an inhaler to nebulizer therapeutic interchange program across a health system. J Pharm Pract. 2023;36(5):1211-6. doi:10.1177/08971900221101761

- Tashkin DP, Lipworth B, Brattsand R. Benefit: risk profile of budesonide in obstructive airways disease. Drugs. 2019;79(16):1757-75. doi:10.1007/s40265-019-01198-7

- Dhand R, Dolovich M, Chipps B, Myers TR, Restrepo R, Farrar JR. The role of nebulized therapy in the management of COPD: evidence and recommendations. COPD. 2012;9(1):58-72. doi:10.3109/15412555.2011.630047

- Santus P, Radovanovic D, Cristiano A, Valenti V, Rizzi M. Role of nebulized glycopyrrolate in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017;11:3257-71. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S135377

- Plaza, V., Giner, J., Rodrigo, G. J., Dolovich, M. B., & Sanchis, J. (2018). Errors in the Use of Inhalers by Health Care Professionals: A Systematic Review. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice, 6(3), 987–995. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.12.032

- van Geffen WH, Carpaij OA, Westbroek LF, Seigers D, Niemeijer A, Vonk JM, et al. Long-acting dual bronchodilator therapy (indacaterol/glycopyrronium) versus nebulized short-acting dual bronchodilator (salbutamol/ipratropium) in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Respir Med. 2020;171:106064. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2020.106064

- Sriram KB, Percival M. Suboptimal inhaler medication adherence and incorrect technique are common among chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Chron Respir Dis. 2016;13(1):13–22. doi: 10.1177/1479972315606313

- Swarnakar R, Dhar R. Call to action: Addressing asthma diagnosis and treatment gaps in India. Lung India. 2024;41(3):209–16. doi: 10.4103/lungindia.lungindia_518_23

- Kocks J, Bosnic-Anticevich S, Cooten J, Correia de Sousa J, Cvetkovski B, Dekhuijzen R, et al. Identifying critical inhalation technique errors in Dry Powder Inhaler use in patients with COPD based on the association with health status and exacerbations: findings from the multi-country cross-sectional observational PIFotal study. BMC Pulm Med. 2023;23(1):302. doi:10.1186/s12890-023-02566-6

- Schreiber J, Sonnenburg T, Luecke E. Inhaler devices in asthma and COPD patients – a prospective cross-sectional study on inhaler preferences and error rates. BMC Pulm Med. 2020;20(1):222. doi:10.1186/s12890-020-01246-z

- Akhoon N, S. Brashier DB. A study to monitor errors in use of inhalation devices in patients of mild-to-moderate bronchial asthma in a tertiary care hospital in Eastern India. Perspect Clin Res. 2022;13(1):17-24. doi:10.4103/picr.PICR_210_19

- Heo YA. Budesonide/Glycopyrronium/Formoterol: A Review in COPD. Drugs. 2021;81(12):1411-22. doi:10.1007/s40265-021-01562-6

- Inhalations for bronchitis: Types and how they work. Medical News Today: August 15, 2023. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/inhalations-for-bronchitis Accessed August 9, 2024.

- Albert RH. Diagnosis and treatment of acute bronchitis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(11):1345-50. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2010/1201/p1345.html

- Kim V, Criner GJ. Chronic bronchitis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(3):228-37. doi:10.1164/rccm.201210-1843CI

- Tashkin DP, Ozol-Godfrey A, Sharma S, Sanjar S. Effect of SGRQ-defined chronic bronchitis at baseline on treatment outcomes in patients with COPD receiving nebulized glycopyrrolate. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2021;16:945-55. doi:10.2147/COPD.S304182

- van Geffen WH, Douma WR, Slebos DJ, Kerstjens HAM. Bronchodilators delivered by nebuliser versus pMDI with spacer or DPI for exacerbations of COPD. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016(8):CD011826. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011826.pub2

- House SA, Gadomski AM, Ralston SL. Evaluating the placebo status of nebulized normal saline in patients with acute viral bronchiolitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(3):250-9. doi; 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.5195

- Huang C, Kuo S, Lin L, Yang Y. The efficacy of N-acetylcysteine in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: a meta-analysis. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2023;17:175346662311585. doi:10.1177/17534666231158563

- Otu A, Langridge P, Denning DW. Nebulised N-acetylcysteine for unresponsive bronchial obstruction in allergic brochopulmonary aspergillosis: a case series and review of the literature. J Fungi. 2018;4(4):117. doi:10.3390/jof4040117

- Agustí A, Celli BR, Criner GJ, Halpin D, Anzueto A, Barnes P, et al. Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease 2023 report: GOLD Executive Summary. Eur Respir J. 2023;61(4):2300239. doi:10.1183/13993003.00239-2023

- Donohue J, Betts K, Du EX, Altman P, Goyal P, Keininger D, et al. Comparative efficacy of long-acting beta-2-agonists as monotherapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a network meta-analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:367-81. doi:10.2147/COPD.S119908

- Oba Y, Keeney E, Ghatehorde N, Dias S. Dual combination therapy versus long‐acting bronchodilators alone for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a systematic review and network meta‐analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2018(12):CD012620. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012620.pub2

- Ferguson GT, Rabe KF, Martinez FJ, Fabbri LM, Wang C, Ichinose M, et al. Triple therapy with budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol fumarate with co-suspension delivery technology versus dual therapies in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (KRONOS): a double-blind, parallel-group, multicenter, phase 3 randomized controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(10):747-58. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30327-8

- Gunen H, Kokturk N, Naycı S, Ozkaya S, Yıldız BP, Turan O, et al. The CO-MIND Study: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Management in Daily Practice and Its Implications for Improved Outcomes According to GOLD 2019 Perspective. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:1883-95. doi:10.2147/COPD.S372439

- Berry RB, Shinto RA, Wong FH, Despars JA, Light RW. Nebulizer vs spacer for bronchodilator delivery in patients hospitalized for acute exacerbations of COPD. Chest. 1989;96(6):1241-6. doi:10.1378/chest.96.6.1241

- Chen Y, Liu Y, Zhang J, Yao W, Yang J, Li F, et al. Comparison of the Clinical Outcomes Between Nebulized and Systemic Corticosteroids in the Treatment of Acute Exacerbation of COPD in China (CONTAIN Study): A Post Hoc Analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2020;15:2343-53. doi:10.2147/COPD.S255475