Optimizing Physical Therapy for Older Adults with Heart Failure

Optimizing Patient Centered Care in the Physical Therapy Management of Older Adults with Heart Failure using the Geriatric 5Ms

Konrad J. Dias, PT, DPT, PhD 1, Kenneth L Miller, PT, DPT, PhD, FNAP 2, Elizabeth A Staats, PT, DPT 3, Keith G. Avin, PT, DPT, PhD 4

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i2.6241

Abstract

The American Physical Therapy Association has published a clinical practice guideline and subsequent knowledge translation document that promote and support evidence-based practice in the management of patients with heart failure (HF). These documents provide physical therapists with a broad base of knowledge related to treatment interventions and the application of these interventions in practice. However, neither document provides insight on explicit management considerations for older adults with HF. The American Geriatric Society and the American Physical Therapy Association’s Academy of Geriatrics call for all geriatric clinicians to use the Geriatric 5Ms (Mind, Mobility, Medications, Multicomplexity, and what Matters Most) framework as a means for optimizing patient-centered care in older adults. This perspective paper aims to provide clinicians with explicit ways to apply and integrate each of the 5Ms when managing older adults with HF. As movement specialists, physical therapists are encouraged to move beyond mobility considerations and appreciate the interactions across the remaining four Ms. This paper highlights patient-centered strategies related to the assessment of cognition, multicomplexity concerns, medication issues, and concepts that matter most to older patients with HF. The integration of all 5Ms in clinical practice allows physical therapists to align their treatment with a similar framework used by other geriatric clinicians thereby promoting interprofessional communication, showcasing value, and encouraging authentic patient-centered care when treating older adults with HF.

Keywords: Geriatric 5Ms, heart failure, physical therapy, patient-centered care, older adults

Introduction

The United States Census Bureau reports that the older adult population over age 65 is the fastest growing age group in the United States. The population of older adults over the of age 65 currently stands at approximately 57.8 million. By 2034 it is estimated that for the first time in the history of the United States older adults will likely outnumber children. As the population of older adults continue to increase, the prevalence of many non-communicable chronic health conditions in older adults also increases. One such condition is heart failure (HF) and is currently considered a significant public health problem in both, the developed and the developing world. Worldwide, it is estimated that approximately 60 million people are living with an established diagnosis of HF. A current report from the Heart Failure Society of America states that over six million Americans have HF, and the prevalence is expected to rise to 8.7 million in 2030, 10.3 million in 2040, and 11.4 million by 2050. Epidemiological evidence confirms that the incidence and prevalence of HF is strikingly age-dependent. Heart failure has not only been noted as the leading cause for hospital admission in adults older than age 65, but also deemed to be the most common diagnosis-related group (DRG) in the Medicare population.

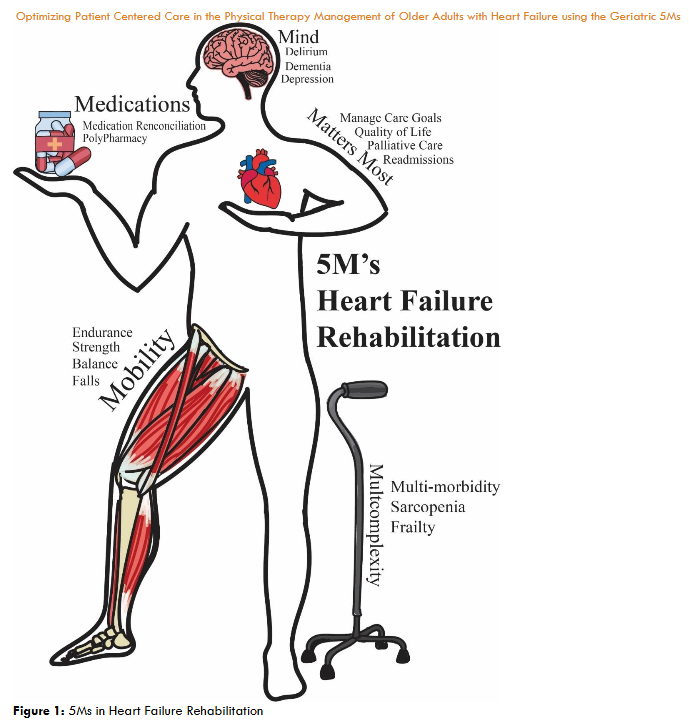

5Ms in Heart Failure Rehabilitation

It is essential for physical therapists to utilize best practice when caring for older adults with HF. In an effort to understand key principles related to managing older adults, the American Geriatric Society eloquently categorizes five key principles for providing age friendly care within the 5Ms framework. The 5 M’s include key proficiencies related to Mind, Mobility, Medications, Multicomplexity, and what Matters Most to the patient. In 2022, the American Physical Therapy Association’s Academy of Geriatrics Academy boldly recommended the use of the Geriatrics 5Ms model as a guiding principle for best practices in geriatric physical therapy. An appreciation and subsequent use of the 5Ms in clinical practice collectively set the stage for a comprehensive approach to providing tailored care for older adults with HF. The 5Ms framework encourages clinicians to provide holistic care through the integration of the 5Ms into their assessment and treatment interventions. Currently, no manuscript or evidence-based resource exists that explicitly delineates how physical therapists can incorporate each of the 5M’s in the rehabilitation of patients with HF. Therefore, the purpose of this perspective paper is to present current empirical evidence on the efficacy of the Geriatric 5Ms in improving patient outcomes for older adults and propose unique ways for physical therapists to integrate and apply the components of Mind, Mobility, Medications, Multicomplexity, and Matters Most in the holistic rehabilitation of older adults with HF.

Methodology

In this review article, author commentary is based on selected articles that have been recently published that highlight considerations related to Mind, Mobility, Medications, Multicomplexity and what Matters Most in patients with HF. Commentary will focus on the ways physical therapist can integrate each of the 5M’s when providing rehabilitation to patients with HF. Authors specifically identify areas of consideration related to applying each of the 5M’s in clinical practice and cite selected research publications for each of M’s included within the 5Ms framework. This article is not a systematic review and so the authors make no claims that the selection of the set of articles is free from bias. The authors simply put forward thoughts for reasonable consideration that can be used in clinical practice. More specifically, this perspective paper proposes key interventions applicable to the physical therapist in incorporating Mind, Mobility, Medications, Multicomplexity, and Matters Most in the holistic care of older adults with HF.

The underlying premise of the article is to propose strategies related to each of the 5M’s, that physical therapists can use to optimize the aging experience. As older adults with HF comprise a heterogenous group with variations in physiological stability, differing levels of activity, and medical complexity, physical therapists and other health care providers must consider applying each of the 5M’s in an effort to provide age-friendly and individualized care to their patients and clients with HF across the continuum of care. The remainder of this article discuss each of the 5 M’s in HF rehabilitation. The article is organized by presenting Mind, Mobility, Medications, Multicomplexity, and Matters Most considerations in separate sections. Each section will first define the respective M. The authors then review selected articles that are relevant and pertinent for physical therapists to consider in clinical practice. Throughout the article, commentary is provided on how physical therapists can integrate and apply Mind, Mobility, Medications, Multicomplexity and Matters Most considerations when treating older adults with HF.

Mind

The 5Ms play a key role in the overall management of age-related and/or pathological changes that are seen with older adults. Mind is the first M to be discussed, as both cognitive function and mood are integral to daily life. The main components of cognitive functioning as described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) are executive functioning, learning and memory, complex attention, language, perceptual-motor functioning, and social cognition. Needless to say, assessing all these components as part of an assessment is a daunting task for both novice and seasoned clinicians alike. For this reason, utilizing the recommendations from the 5Ms framework helps simplify the assessment of cognitive function by focusing on three important cognitive criteria that include dementia, depression, and delirium (also known as the 3Ds). There are several screening tools available to determine the presence of and differentiate the 3Ds in clinical practice. Several of these tools have become mandatory assessment items dictated by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services including the Brief Interview for Mental Status (BIMS), Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2 or PHQ-9) and the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM). The BIMS, PHQ-2 and CAM are quick screening tools used to assess the presence of cognitive impairment suggestive of dementia, depression and delirium respectively.

| Term | Definition | Screening Tool |

|---|---|---|

| Delirium | An acute change in mental status (inattention and disorganized thinking) that develops over hours or days and has a fluctuating course. | Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) |

| Dementia | Is a significant change in cognitive performance from a previous level of performance in one or more cognitive domains that interferes with functioning in daily life. | Brief Interview for Mental Status (BIMS) |

| Depression | Is a spectrum of mood disorders characterized by a sustained disturbance in emotional, cognitive, behavioral, or somatic regulation that is associated with a change from a previous level of functioning or clinically significant distress. | Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2 or PHQ-9) |

Each of the 3Ds have been shown to significantly impact morbidity and mortality in patients with HF. As depression is under detected in older adults with HF, and delirium often confused with dementia, the 3Ds have been shown to have major adverse health effects including an increase in mortality in patients with HF.

Mobility

The mobility component of the Geriatric 5Ms focuses on maintaining or improving the ability of older adults to move safely and effectively. HF is characterized by reduced oxygen delivery and fluid retention, presenting with fatigue, shortness of breath, chest pain, leg swelling, and weakness. These symptoms limit physical activity and contribute to sarcopenia and/or frailty. HF is commonly classified using the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification, ranging from stage I (no physical activity limitations) to stage IV (inability to perform any physical activity without discomfort, with symptoms even at rest). Those with HF often experience a decline in aerobic capacity, impaired balance, and weakness, leading to increased falls, hospitalization, and mortality. Limitations in mobility and physical activity can deteriorate musculoskeletal health across the spectrum of sarcopenia and frailty. Focusing on mobility within the Geriatric 5Ms should promote activities that account for individual capabilities and goals, engaging in daily and leisure activities, and life-long exercise to improve overall health and well-being.

Physical therapists should recognize that mobility includes screening, assessment, intervention, and education, with considerations of 1) safety and fall risk, and 2) improving performance, mitigating decline, or preventing onset. Safety and fall risk are significant concerns for those with HF. When hospitalized, there is a moderate-to-high risk (>60%) for falls regardless of age. When HF is co-occurring with arrhythmias, showing evidence of multicomplexity, there is a 43% fall rate compared to 30% for people that fall in the presence of other chronic diseases. Falls in those with HF may occur due to reduced cardiac output, arrhythmias, fluid changes, polypharmacy, and interactions with other comorbid conditions. It has been shown that patients with HF have significantly poor metrics on balance tests and measures including total Mini-Balance Evaluation Systems Test scores, reactive postural control, gait stability scores, significantly higher Timed Up and Go Test, and Dual Task Timed Up and Go Test scores, lower Activities Specific Balance Confidence Scale score, slower gait speed, and decreased stride length, gait cycle, and step length. These data highlight the importance for physical therapists to include appropriate tests and measures that assess balance and fall risk in older patients with HF. The results of these assessments in clinical practice across the continuum of care will objectively inform the clinician about the patients fall risk and the need to include appropriate balance and gait training interventions to improve the patient’s overall gait, balance and fall risk. Additionally, it is important to note that older adults are often reluctant to discuss falls. For this reason older patients with HF need to be appropriately screened by asking if they have fallen in the past year, with subsequent follow-up screening and management of falls. Detailed guidelines for screening and managing falls in older adults and risk factors are provided by Lusardi et al. and Avin et al. and Denfeld et al. respectively. Regardless of where the patient is along the spectrum of HF, the goal of physical therapy is to prevent acute exacerbations, improve performance, and mitigate decline. When treating patients with HF, appropriate management considerations were compiled by an APTA clinical practice guideline development workgroup group that published a clinical practice guideline document and an accompanying knowledge translation resource.

| Physical Activity Recommendations for Older Patients with Heart Failure |

|---|

| General Activity Recommendations • Take as many breaks as you need. Use the Ratings of Perceived Exertion and Dyspnea scales rather than heart rate to measure your intensity. • Perform warm and cool-down period to start and end exercise session. |

| Safety Recommendations • Closely monitor your intensity level. Adjust your workout if you feel fatigued. • Stop exercising right away if you feel chest pain or angina. Contact your physician if you have chest pain, labored breathing, or extreme fatigue. • With some diagnoses, you should not exercise. These include obstruction to left ventricular outflow, decompensated heart failure, or unstable variable heart rate. • Avoid high resistance, static position (or isometric) contractions. • Avoid holding your breath when lifting. This can cause large changes in blood pressure. That change may increase the risk of passing out or developing abnormal heart rhythms. Be especially careful if you have high blood pressure. • If you have joint problems or other health problems, do only one set for all major muscle groups. Start with 10 to 15 repetitions. Build up to 15 to 20 repetitions before you add another set. |

| Aerobic Exercise • Frequency: Be active on most days of the week but at least three to four days. Work up to five days a week. • Intensity – Exercise at a moderate level. Use the “talk test” to help you monitor. For example, even though you may notice a slight rise in your heart rate and breathing, you should be able to carry on a conversation while walking at a moderate. • Time: Exercise 30-60 minutes per day. Begin with multiple 10 minutes sessions with gradual increase to 60. • Choose low-impact activities (i.e., walking, cycling) • Begin with low-intensity and longer duration over high-intensity workouts. |

| Resistance Exercise • Begin with high-repetition, low-resistance circuit training two to three times per week. • Frequency – At least two days per week. • Intensity – Moderate level is lifting a 10-15 High level is when you can lift a weight only eight to ten times. • Time – Dependent on number of exercises • Type – All major muscle groups using any type of resistance |

| Stretching • Include range-of-motion/stretching exercises |

| Goal Setting • Keep simple • Improve mobility, make your daily activities easier, and increase your overall fitness. |

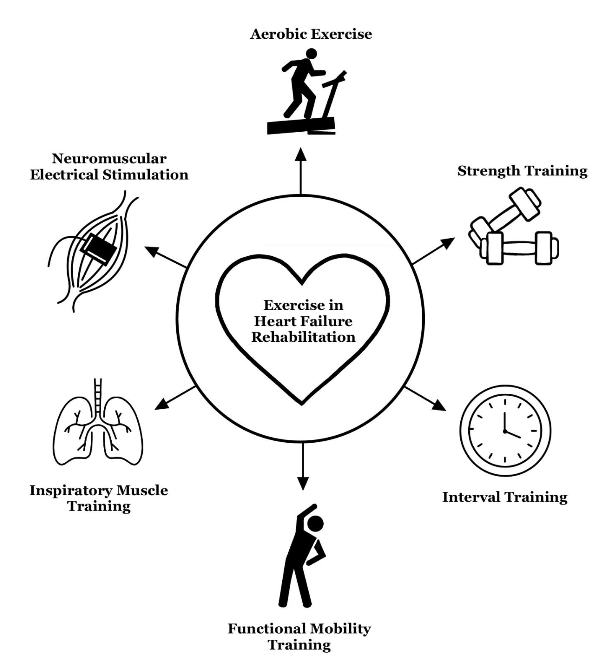

Mobility-related recommendations from the HF clinical practice guideline were emphasized for patients living with stable HF, and do not account for complex, multimorbid patients with more significant impairments in physical activity and participation. For this reason, the knowledge translation framework provided a practical approach in managing mobility issues in older adults with HF across the continuum of care. Within the knowledge translation resource, Dias et al. propose a five step ABCDE framework in the overall management of patients with HF. The five steps include the Assessment of Stability, Behavior Modification, Cardiorespiratory Assessment, Dosage of Interventions and Education. The first component of the framework relates to a formal assessment of patient stability. The authors recommend evaluating stability from an absolute and relative perspective during routine evaluations to help identify if the patient is decompensating. The second component of the framework relates to behavior modification. Exercise and activity are often not a part of a patient’s lifestyle and thus requires behavioral modification in an effort to improve overall activity and participation. The third component involves purposeful use of outcome measures to measure cardiorespiratory fitness in older patients and clients with HF. Fourthly, a variety of interventions including aerobic exercise, functional mobility training, interval training, strength training, inspiratory muscle training, and use of neuromuscular electrical stimulation can be provided to patients with HF.

Finally, education, the fifth component of the framework, emphasizes chronic disease management, focusing on recognizing HF exacerbation signs, nutritional recommendations, and medication management.

Medications

Medication management for older adults with HF focuses on identifying polypharmacy and inappropriate prescription that is predicated upon timely interprofessional communication and medication reconciliation. Polypharmacy recognition is the first and foremost important attribute for the management in older adults. Older adults commonly have multiple chronic conditions alongside their diagnosis of HF, where physicians may prescribe multiple medications for each condition thereby resulting in several medications that the patient is required to consume each day. 94.9% percent of adults age 60 and older have at least one condition, while 78.7% are prescribed with two or more medications. The common numeric cutoff of > 5 medications is frequently used in defining polypharmacy and is commonly seen in patients with chronic diseases. Polypharmacy can lead to unfortunate side effects that can affect the other 4Ms. Physicians are constantly prescribing and deprescribing medications. This may often confuse the patient thereby resulting in the patient not consuming the appropriate regimen of medications. To help with appropriate medication use, physical therapists have the unique ability to participate in medication reconciliation. The process of medication reconciliation involves a review of daily medications being taken by the patient compared to physical prescription, checking for interactions, duplications, omissions, contacting the physician to collaborate as needed, and educating the patient regarding all medications being prescribed for the patient during the episode of care. Within the home care setting, physical therapists are encouraged to visualize every medication bottle and enter that medication onto the patient’s medication profile at admission, on the second visit, and at all mandated points in time including recertification, resumption of care and discharge. Additionally, physical therapists should contact the physician regarding any noted discrepancies or interactions. By incorporating this formal process of medication reconciliation within home healthcare, physical therapists can work collaboratively with physicians in ensuring their patients with HF are not being overly prescribed with medications that may be causing adverse interactions and side effects.

| Medications for the Management for Chronic Heart Failure |

|---|

| Drug Class Mechanism of Action Possible Side Effects PT Considerations |

| Beta Adrenergic Blocking Agents (Beta Blockers) • β1 selective: Bisoprolol (Zebeta), Metoprolol (Lopressor, Toprol) • Nonselective: Carvedilol (Coreg CR) Common suffix: olol Decreases myocardial oxygen demand, relaxes blood vessels, and decreases HR, leading to improve contractility over time Common: bradycardia, fatigue, exercise intolerance, hypoglycemic symptoms can be masked Use Rate of Perceived Exertion scale due to lack of heart rate response to exercise, monitor for orthostasis and bradycardia, check blood sugar in patients with diabetes before exercise |

| Renin-Angiotensin System (RASS) Inhibition • Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitors: Captopril (Capoten), Enalapril (Vasotec). Lisinopril (Prinivil) Common suffix: pril • Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers (ARBs): Azilsartan (Edarbi), Irbesartan (Avapro), Losartan (Cozaar) Common suffix: sartan • Angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ARNi): Sacubitril/Valsartan (Entreso) Slightly different mechanism of action depending on type. Overall goal is to block angiotensin II, which will decrease sodium and water retention, leading to decreased blood pressure and preload Common: dry cough, hypotension, dizziness, hyperkalemia Serious: renal failure, angioedema, anaphylaxis, neutropenia Monitor for changes in weight, urine output, muscle cramps, s/s of angioedema, vitals, and lab values for electrolyte imbalances |

| Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists (MRAs) • Spironolactone (Aldactone, Alatone) • Eplerenone (Inspra) Common suffix: one Decreases preload and reduced myocardial oxygen demand, and improved contractility Hypotension, orthostasis, hyponatremia, hypoglycemia, dehydration Monitor for changes in weight, urine output, vitals, and lab values for electrolyte imbalances |

| Sodium Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitor (SGLT2i) • Dapagliflozin (Farxiga) • Empagliflozin (Jardiance) Common suffix: flozin Blocks reabsorption of glucose and sodium in kidneys, resulting in increased urine output, leading to decreased preload and workload of the heart Hypotension, orthostasis, hyperkalemia, hyponatremia, hypoglycemia, dehydration, UTI, diabetic ketoacidosis Monitor for changes in weight, urine output, blood sugar, and lab values for electrolyte imbalances |

In addition to medication reconciliation, two useful tools exist to assist clinicians with screening for polypharmacy and ensure medication optimization, such as the American Geriatric Society Potentially Inappropriate Medication List (Beers Criteria), the Screening Tool of Older People’s Prescription (STOPP). The Beers Criteria is a database that provides guidance on medications that should be avoided for most older adults and medications that should be avoided with older adults with certain conditions such as heart failure. Clinicians can utilize the Beers Criteria to understand drug class, rational for why a drug may potentially be inappropriate, strength of recommendations, and related quality of evidence for that medication. Physical therapists have the unique opportunity to identify their patients with HF that may be taking potentially inappropriate medications, examine for side effects, and report the findings back to the prescribing clinician. An example of possibly inappropriate medications for older adults with HF may be use of non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers such as diltiazem and verapamil which can worsen symptoms of heart failure due to their negative inotropic effect. This negative inotropic effect leads to reduced cardiac output and aerobic capacity, which in turn effects the Mobility M. Additionally, first generation antihistamines that reduce allergy symptoms and improve sleep have the potential to increase the risk of confusion, delirium, falls, and dementia with cumulative exposure, highlighting how the Medication M can also impact the Mind M. Diphenhydramine, also known as Benadryl, is an example of a first gen antihistamine that is also found in Advil PM and Motrin PM. It is important to note that outside the hospital setting older adults may be taking over the counter medications without the knowledge of their physician. Through a formal process of medication reconciliation and by being aware of the medications listed on the Beers Criteria, physical therapists can identify drugs that may be inappropriate and report them back to the prescribing physician to maximize safety.

Multicomplexity

Multicomplexity reflects the intricate and interconnected health challenges often faced by older adults. Multicomplexity accounts for the primary medical condition(s) but also the combined and interactive effects of multiple chronic diseases, functional limitations, cognitive impairments, social factors, and psychological aspects. Appreciating the interacting elements within a single individual is the foundation of holistic care. Older adults with HF often have multiple chronic conditions along with acute episodes of their life-threatening illness. Johnston and colleagues empirically define multimorbidity as the presence of two or more chronic conditions in the same individual. Physical therapists are often challenged in providing disease-specific interventions for a specific condition such as HF, when treatment for one condition adversely affects another condition. Empirical evidence reveals approximately 80% of patients with HF have greater than four non-cardiovascular comorbidities. Physical therapists often recognize that the burden of comorbidities in older patients with HF amplifies reduced physical activity, perpetuates a sedentary lifestyle, and reduces overall activity and participation.

| Physical Therapy Assessment Considerations when Managing Older Adults with Heart Failure Rehabilitation and Multiple Comorbidities |

|---|

| Comorbid Condition Physical Therapy Assessment Considerations |

| Diabetes Assess for peripheral neuropathy, balance impairment, fall risk, and symptomology associated with hyper/hypo glycemia. |

| Chronic Renal disease Assess glomerular filtration rate, urine output, biomarkers including blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, calcium and vitamin D levels. |

| Osteoarthritis Assess pain, joint stiffness, muscle weakness and titrate dose of intervention based on the severity of symptoms. |

| Atrial fibrillation Close monitoring of pulse rate and rhythm during exercise along with assessment of balance and fall risk in older individuals receiving anticoagulation therapy. |

| Obstructive or restrictive lung disease Assess pulse oximetry as a measure of hypoxemia. Assess respiratory rate, and dyspnea in an effort to provide the appropriate the dose of exercise. |

| Hypertension Assess blood pressure at rest and with exercise. Monitor for orthostatic hypotension or blood pressure alterations with positional changes. |

| Obesity Assess for problems with sleep due to sleep apnea, diet and lifestyle, as well as muscle and joint pain and reduced exercise tolerance caused by increased body fat. |

Recent evidence has confirmed frailty to be an important consideration in the management of older patients with HF due to its high prevalence and prognostic significance. It is estimated that approximately half of all patients with HF are frail. Additionally, a recent systematic review indicates that frail older individuals with HF carry a 50% higher risk of both hospitalization and mortality compared with older individuals with HF that are not frail. Given the increased prevalence of frailty coupled with its clinical significance, it is imperative that physical therapists integrate frailty assessment when treating older patients with HF. In regard to frailty assessment, the so called “eyeball test” or assessment of frailty with mere visual observation has been shown to be markedly unreliable especially over age and weight spectrums. Frailty has been conceptualized using two major approaches including the assessment of physical frailty measured by Fried’s Frailty Phenotype Criteria and multidimensional frailty assessed by Rockwood’s Frailty Index. Fried conceptualizes the Frailty Phenotype Criteria as a cycle in which multiple body systems including the endocrinological, musculoskeletal, digestive and other systems collectively produce a clinical syndrome associated with increased vulnerability to stressors. Fried defines frailty as “a biologic syndrome of decreased reserves and resistance to stressors, resulting from cumulative declines across multiple physiologic systems, and causing vulnerability to adverse outcomes.” The assessment of frailty based on the Fried criteria call for the assessment of five components including weight loss, weakness, slowness, low physical activity, and exhaustion. Physical therapists can classify patients as being frail when 3 of 5 criteria are met, and prefrail and non-frail when 1 to 2 and 0 criteria are met. Alternatively, Rockwood and colleagues have designed the Frailty Index in which frailty is assessed through a sum of age-related deficits including functional impairments, biochemical abnormalities, symptoms, signs, and comorbidities. The Frailty Index is reported as a value between 30 and 70 which is calculated as a ratio of the actual deficits to the total number of deficits assessed. In addition to the examination of frailty, screening for sarcopenia is another valuable assessment in older adults with HF. The prevalence of sarcopenia in HF is 20% higher than in age-matched controls, potentially due to a muscle fiber transition from type I to type II myofibers. Sarcopenia screening, as recommended by the International Conference of Frailty and Sarcopenia Research Clinical Practice Guidelines for Sarcopenia advocate for the use of gait speed as a surrogate assessment in identifying sarcopenia. Based on the evidence Dent et al report a score of less than 0.8 meters per second as a cut-off score in recognizing possible sarcopenia in older adults. Additionally, gait speed is a particularly important assessment in older adults with HF as functional capacity and balance have been shown to independently influence gait speed in patients with HF. Finally, it is important for physical therapists to recognize the importance of sarcopenia and frailty in the overall management of older adults with HF. Including screening of frailty and sarcopenia in practice help physical therapists recognize that muscle weakness is often evident in older patients and contributes to falls, fatigue, and reduction in the patient’s ability to do daily activities. The transition of muscle fiber properties further exacerbates fatigue. For this reason, physical therapists must make every effort to evaluate peripheral muscle strength through traditional manual muscle testing or dynamometry. Multicomplexity is enormously prevalent in older patients with HF and its presence predicts a worse prognosis. In light of complications from multicomplexity, physical therapists are called to recognize the heterogeneity of their older patients with HF by identifying the number of comorbid conditions and where the patient may be along the spectrum from fit to frail, using a validated screening tool. Physical therapists are encouraged to evaluate each comorbid condition, and work with the interprofessional team to address each condition. Effective screening and assessment of sarcopenia, frailty and peripheral muscle strength are each individually crucial in the overall management of older patients with HF, as these assessments help tailor interventions to improve physical performance and mitigate decline.

Matters Most

The APTA Academy of Geriatric Physical Therapy has incorporated Matters Most M as part of the first guiding principle of geriatric physical therapy practice in the United States. This first guiding principle reads as follows: “Utilize person centered care to elicit and prioritize the individual’s preferences, values, and goals to drive the plan of care.” When thinking about what matters most to older patients in practice, physical therapists must consider care preferences, health outcome goals, and intentionality, to focus on what is truly important to the patient or clients being served during any episode of care. The American Geriatric Society provides key tips for all geriatric clinicians to consider as components of the Matters Most M. These include consideration of personalized care goals, shared decision making, utilizing a holistic approach to treatment, and advance care planning. These four themes provide a useful framework for physical therapists to also use when working with older individuals with HF. The answer to the explicit question, “what matters most?” can help physical therapist with goal setting and care planning by prioritizing what is truly important to the patient. Individual patient goals are variable from one patient to another ranging from a patient hoping to maintain independence, or reduce pain, avoid hospitalizations, or minimize disease exacerbations. Through the process of shared clinical decision making, physical therapists can create patient-centered goals and care plans that reflect the values and preferences of their older patients with HF and caregivers. A holistic approach considers the patient’s physical, emotional, social and spiritual needs when providing care. In physical therapy practice, holistic care for older patients with HF is contextualized by considering fall/balance, the patient’s current level of functional mobility, general health rating, medications, continence, vision and hearing, mental health, social network and support, societal roles, and environmental factors in the overall management of the patient. In the context of what matters most in heart failure rehabilitation, it is essential for physical therapists to identify the current stage of HF of their patient or client. The American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology categorizes patients into one of four stages based on the severity of HF. In Stage A and Stage B HF, patients are at risk or in a stage of pre-HF, while patients categorized in Stage C and Stage D HF have overt symptomatic HF or advanced HF, respectively. It is important for physical therapists to recognize that what matters most to patients is variable across the four stages of HF. A patient in Stage A or at risk for HF may have goals of improving activity, reducing weight, and improving lifestyle to reduce the likelihood of progressing to higher stages of HF. Alternatively, a patient living with Stage C or overt symptomatic HF may have a specific goal of being able to go shopping without symptoms of fatigue and short of breath that limit their activity and participation.

Another important consideration in the matters most M involves advance care planning. Advance care planning occurs throughout all the four stages of HF but may be most impactful during stage D HF, where patients are living with advanced and end-stage disease. As its name reflects, advance care planning involves purposeful planning for the future healthcare preferences of the patient, including end-of life care, by ensuring that the patient’s wishes are respected. It takes an interdisciplinary team to facilitate appropriate advance care planning and physical therapists can be involved in helping patients understand their options through ongoing conversations. Through conversations during clinical care, physical therapists can understand the patient’s values, goals, and preferences, and facilitate collaboration with other members of the interprofessional team to ensure that the patient’s wishes are being fulfilled. Finally, what often matters most to patients with overt Stage C and advanced Stage D HF is reducing hospital readmissions. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has included HF in the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) due the increased risk of rehospitalization to encourage hospitals to improve communication and care coordination in hopes of reducing readmissions. The HRRP directly aligns with patient preference with getting better and going home. Patients reported feeling better or more comfortable at home. For this reason, physical therapy researchers and clinicians should design novel programs to reduce readmission as this is a “matters most” issue for older adults with HF. Physical therapists are encouraged to adapt the components of the Matters Most M into their practice. This is facilitated by creating individualized patient-centered goals based on the patient’s values, beliefs and preferences; include the patient with shared decision-making, be holistic with assessment and care planning, and facilitate conversations with the patient and collaboration with the interprofessional team for effective advance care planning.

Conclusion

The APTA Academy of Geriatrics advocates that all clinicians working with older adults follow the Geriatric 5Ms framework in an effort to provide patient-centered care. To this end, this perspective paper guides physical therapists on explicit ways to apply and integrate mind, mobility, medications, multicomplexity, and what matters most in the holistic management of older adults with HF. Through a formal assessment of the 3Ds (delirium, dementia and depression), polypharmacy, medication reconciliation and collaborating with physicians to deprescribe, selecting and dosing skilled interventions to maximize mobility, considering multimorbidity, frailty, and sarcopenia physical therapists can mitigate HF-related hospitalizations and readmissions, and in turn optimize overall movement to improve the human experience in older adults with HF.

Acknowledgments: We sincerely thank Ms. Ashton McCormick and Ms. Jodi Engelhardt for their creativity and assistance in creating the graphics and artwork for Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

Conflict of Interest: None declared

References

- Older Population and Aging. Accessed December 15, 2024. https://www.census.gov/topics/population/older-aging.html

- An Aging Nation: Projected Number of Children and Older Adults. Accessed December 15, 2024. https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2018/comm/historic-first.html

- Roger VL. Epidemiology of Heart Failure: A Contemporary Perspective. Circ Res. 2021;128(10):1421-1434. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.318172/FORMAT/EPUB

- Abba…