Oral Biofilms and Cardiovascular Health: A Critical Link

Oral Biofilms and Their Connection to Cardiovascular Health

Gregori M. Kurtzman DDS1, Robert A. Horowitz, DDS2, Richard Johnson, MD3, Jayden Prestiano4

- Gregori M. Kurtzman, DDS General Dentistry and Implantology, General Dental Practice, Silver Spring, USA

- Robert A. Horowitz, DDS Periodontology, New York University College of Dentistry, New York, USA

- Richard Johnson, MD Internal Medicine, Retired, New York, USA

- Jayden Prestiano University of Miami, Miami, Florida, USA

OPEN ACCESS

Published: 31 May 2025

CITATION: Kurtzman, GM., Horowitz, RA., et al., 2025. Oral Biofilms and Their Connection to Cardiovascular Health. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(5). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i5.6585

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i5.6585

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

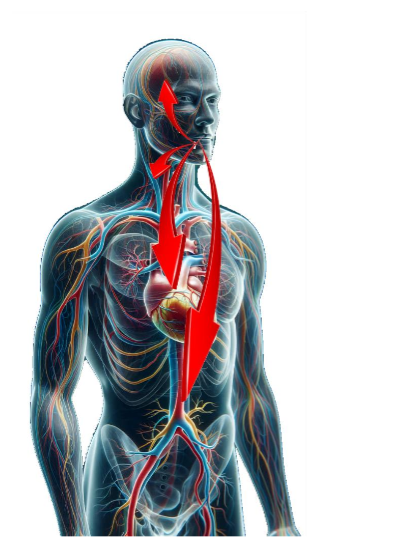

Systemic and oral health are interconnected via bacteria in the oral biofilm and their byproducts which can circulate throughout the body. Oral biofilm and its associated periodontal health have not been frequently addressed in patients with systemic health issues, especially cardiac related health. This is especially true for those patients who do not respond to medical treatment for their cardiac health issues via their physician. The periodontal sulcus around the teeth in the absence of the clinical evidence of periodontal disease (bleeding on probing or brushing, gingival inflammation) may have oral biofilm present. Inflammatory reaction is patient dependent on their immune response to the associated bacteria and their byproducts present in the oral biofilm. Increasing evidence has emerged in recent years connecting oral biofilms with systemic conditions including cardiac related issues, either by initiating them or by complicating those medical conditions. The patient’s health needs to be considered as a whole-body system with connections that may originate in the oral cavity and have distant effects throughout the body. In order to maximize the patient’s total health, healthcare needs to be a coordination between the physician and dentist to eliminate the oral biofilm and aid in the prevention of systemic disease or minimize those effects to improve the overall patient health and their quality of life. This article will focus on oral biofilm, and its connection to cardiovascular health.

Keywords:

- Oral biofilm

- Cardiovascular disease

- Stroke

Introduction

Physicians are in a unique position to treat total health, as they manage their patient’s systemic health. They may be the first healthcare practitioner to identify the presence of systemic issues or manage these systemic health issues. The patient’s health needs to be considered as a whole-body system with connections that may originate in the oral cavity and have distant effects throughout the body. Yet, the dentist is the healthcare provider to identify and treat oral biofilm that may be present. To maximize total health, coordination in healthcare needs to be a symbiosis between the physician and dentist to eliminate the oral biofilm and aid in the prevention of systemic disease, while minimizing these effects to aid in improving the patient’s overall health and quality of life. This “team approach” thus needs to be a coordinated effort between the physician and dentist to aid in eliminating factors that may be causing systemic issues. Evidence has increasingly emerged in recent years connecting oral bacteria within the biofilm with cardiac health, either initiating those conditions or complicating those cardiac conditions.

The purpose of this article is a review of the literature discussing oral biofilm, and its cardiac effects aid on the connection between the oral environment and this aspect of systemic health.

What is an Oral Biofilm?

Oral biofilm, formally referred to as dental plaque as its complex nature has emerged in the literature, has long been associated with periodontal disease and, to a lesser extent, dental caries (tooth decay). Those dental issues relate to the bacteria contained within the oral biofilm, yet oral bacterium has long been ignored for any effects outside the oral cavity. Research has been accumulating directly connecting a link between oral health and systemic disease, with a reported 200 possible connections between systemic diseases and oral health being reported by the American Dental Association. Accumulating evidence has linked chronic oral inflammation associated with periodontal disease to multiple health conditions, which includes cardiovascular disease, renal issues, diabetes, osteoporosis, pulmonary disorders, Alzheimer’s disease, and other systemic conditions. Oral biofilm has been recognized, related to available research, as a more complex environment than previously understood. Oral biofilm is a microorganism community found on the tooth’s surface or within the gingival sulcus (periodontal pocket). Those bacteria are embedded in a matrix of polymers. Over 700 different species of bacteria naturally reside in the mouth, with most being considered innocuous, but some of those microorganisms have been identified as pathogenic. As the bacterial number increases at the site, those microorganisms create an intricate network of protective layers (i.e., matrix) developing into a biofilm. This is the major cause of periodontal disease. The biofilm protects those bacteria making them less susceptible to antimicrobial agents, either locally or systemically administered. Whereas planktonic bacteria are not protected by the biofilm making them susceptible antimicrobial agents. Those biofilm microbial communities have demonstrated enhanced pathogenicity (pathogenic synergism). Additionally, the biofilm’s structure restricts penetration of antimicrobial agents, while bacteria growing on a surface (planktonic) are susceptible to antimicrobial agents. Thus, oral biofilm bacteria has been reported to provide drug resistance to antibiotics and other medicaments making it difficult to chemically control those microorganisms. Aggregation allows the bacteria work together as a community, producing specific proteins and enzymes via quorum sensing, utilizing oral fluids as the vector for transmission. In those oral environments microorganisms have evolved as part of multispecies biofilms requiring interaction with other bacterial species to grow, forming complex bioenvironments. Quorum sensing, a cell-to-cell communication mechanism synchronizes gene expression in biofilms in response to the density of the cell population gives those bacteria the ability to regulate numerous processes. This includes secretion of specific enzymes to activate or inhibit the genes of other bacteria with those bacterial byproducts provoking a host immune response. That immune response causes recruiting of host white blood cells (WBCs) to the site to kill the invading bacteria, resulting in localized inflammation in the surrounding gingiva. Those bacteria using quorum sensing, have the ability to confuse the hosts WBC chemotactically, releasing chemicals into the local environment. Thus, rendering the hosts immune response ineffective. Since WBCs have a 3-day life cycle, if they do not engulf a microorganism and destroy it within that time frame, the WBC’s lyse and die. Therefore, components within the WBC that were intended to kill bacteria are now available to damage the very tissue they were meant to protect. This contributes to periodontal bone loss and gingival inflammation resulting in the deepening of periodontal pockets. Biofilm bacteria are a diverse community, with variations in the many species being detected. The biome in the same patient can be different from site to site. Once the biofilm is formed, the contained species composition has a degree of stability at a site among component species due to a balance between synergism and antagonism. The biofilm in periodontal pockets is most likely to be seen in its mature state as these areas provide protection from homecare removal by the patient. As the biofilm matures, the microbial composition changes from one that is primarily gram-positive and streptococcus-rich to a biofilm filled with primarily gram-negative anaerobes. Initially, the biofilm biome consists of predominately gram-positive cocci bacteria (Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus oralis, Streptococcus sanguis, Streptococcus mitis, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Rothia dentocariosa), that is followed by some gram-positive rods and filament’s (Actinomyces gerencseriae, Actinomyces viscosus, Actinomyces israelis and Corynebacterium species). This also includes a very small number of gram-negative cocci, with Veillonella parvula and Neisseria species, that comprise some of the gram-negative cocci, that are aerobes or facultative aerobes. The early biofilm is able to withstand frequent mechanisms of oral bacterial removal, such as swallowing, chewing, and salivary fluid flow. Those early colonizers are able to survive high oxygen concentrations in the oral cavity. This initial biofilm, which is always present orally, forms immediately after cleaning via toothbrushing or professional dental prophylaxis. Co-adhesion of later bacterial colonizers to the initial biofilm involves specific interactions between bacterial receptors, which increases the volume of the biofilm. This results in a more complex and diverse biome environment. These diverse bacterial species then create synergistic and antagonistic biochemical interactions among the inhabitants of the colony, metabolically contributing to bacteria that are physically close to them. When obligate aerobes and anaerobes are involved in co-adhesion, those interactions aid in the survival of anaerobic bacteria in the oxygen-rich oral cavity. Those bacteria continue to divide until a mixed-culture biofilm that is specially and functionally organized has formed. Bacterial inhabitant polymer production leads to the development of an extracellular matrix, which is a key structural aspect of the biofilm. That matrix offers microbial inhabitants protection from external factors. As the biofilm thickens while it matures, anaerobic bacteria are able to live deeper within the biofilm, further protecting them from the oxygen-rich environment within the oral cavity. Patients with oral biofilms do not need to present with gingival bleeding to have systemic issues related to the microorganisms in the biofilm. Identification of the presence intraorally is directed by the dentist to identify the presence or absence of periodontal disease in that particular patient. The presence and severity of periodontal disease varies according to the patient’s immunological response to the bacteria in their biofilm. Some patients may present with typical signs of periodontal disease, such as bleeding on probing or brushing, and gingival inflammation. However, other patients do not present with these typical periodontal signs. Those harmful strains of bacteria in the oral biofilm may enter the bloodstream spreading to other areas of the body, in this case cardiac related issues may result during the inflammatory response. Wherein they can exert distant systemic effects that have been linked to numerous diseases. Increasing evidence has been reported that indicates patients with periodontal disease have a much higher risk of developing cardiovascular and other systemic issues than those individuals who take preventive measures to eliminate and control their oral biofilm.

Cardiac disease:

Cardiac disease has been linked to oral biofilm through the influence of oral bacteria and the inflammatory response resulting from conditions like periodontal (gum) disease. While the exact mechanisms are still being studied, research suggests that the bacteria present in oral biofilm can have a direct or indirect impact on heart health. There are significant ways that oral biofilm can contribute to cardiac disease. The bacteria in oral biofilm, can lead to periodontal disease, a condition that causes inflammation of the oral soft tissues. This chronic low-grade inflammation can then spread throughout the body. Since inflammation is a critical factor in the development of atherosclerosis, it is a major risk factor for heart disease, stroke, and peripheral artery disease. Additionally, periodontal disease is associated with higher levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), a biomarker of systemic inflammation. Elevated CRP levels are linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, including heart attacks and stroke. Higher CRP levels are often seen in individuals with periodontal disease. When gingiva is inflamed or bleeds (common in periodontal disease), oral bacteria can enter the bloodstream, leading to bacteremia, and then travel to other parts of the body, including the heart. Those oral bacteria may attach to the heart valves, especially in individuals with pre-existing heart conditions, potentially leading to infective endocarditis. Some oral bacteria, such as Porphyromonas gingivalis, Streptococcus sanguinis, and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans have been found to interact with platelet function, potentially promoting blood clot formation, and increasing the risk of heart attacks or stroke. The endothelial cells can be adversely affected by systemic inflammation and bacterial infection originating from the mouth. Damage to the endothelium can lead to impaired vascular function, contributing to the development of atherosclerosis and other cardiovascular issues. Those who already have risk factors for heart disease, such as hypertension, diabetes, or a family history of cardiovascular disease, may be more susceptible to the impact of oral biofilm. These individuals may be at an even greater risk of developing cardiac issues related to oral health problems. Oral biofilm, particularly when it leads to periodontal disease, can contribute to atherosclerosis in several ways. The chronic inflammation caused by periodontal disease can increase systemic inflammation, which is a key factor in the development of atherosclerosis. Bacteria from oral biofilm can attach to the arterial walls, contributing to plaque formation and arterial damage. The bacteria from oral biofilm can induce endothelial dysfunction by promoting inflammatory responses and the release of reactive oxygen species (ROS) from the endothelium. The endothelial lining of blood vessels plays a crucial role in maintaining vascular health, and its dysfunction is a critical early event in the development of atherosclerosis. Periodontal disease causes systemic inflammation, which can lead to the accumulation of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol in the walls of arteries. This process, known as lipid oxidation, is a significant factor in the formation of atherosclerotic plaques. Systemic inflammation driven by oral biofilm may also contribute to the oxidation of LDL, further accelerating atherosclerosis. Additionally, periodontal inflammation can trigger inflammatory processes that damage coronary arteries. This can lead to a higher likelihood of plaque rupture and clot formation, which are common causes of heart attacks. Stroke risk is also increased with oral bacteria accumulation in the brain and is similar to heart disease, the build-up of plaques in the arteries can increase the risk of ischemic stroke. Those oral bacteria potentially contribute to the formation of emboli. Though the link between oral biofilm and hypertension is less direct, some studies suggest that periodontal disease and systemic inflammation associated with oral biofilm may influence blood pressure regulation. Chronic inflammation could contribute to the development or worsening of hypertension, a known risk factor for heart disease. There is some evidence suggesting a possible link between oral health and heart failure. Chronic oral infections might contribute to the ongoing inflammation that weakens heart function, particularly in individuals who already have cardiovascular issues. The inflammatory burden caused by untreated oral biofilm may contribute to the overall strain on the heart. Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) a leading cause of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality worldwide. Growing evidence has suggested a link between oral biofilm, and the development of coronary artery disease (CAD). The connection is primarily mediated through systemic inflammation, bacterial translocation into the bloodstream, and endothelial dysfunction. A study suggests that the presence of oral bacteria in the bloodstream may trigger immune responses that damage blood vessels, contributing to CAD. Furthermore, the role of oral infections in the progression of cardiovascular diseases like CAD, contribute to lipid accumulation and plaque formation. Another study supports the hypothesis that periodontal pathogens may play a direct role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, contributing to CAD. The mechanisms underlying this association involve systemic inflammation, bacterial translocation into the bloodstream, and endothelial dysfunction. Several studies have suggested Myocardial Infarction (MI) has a link with oral biofilm. The relationship between oral health and MI is thought to be mediated through systemic inflammation, bacterial translocation, and endothelial dysfunction, all of which contribute to the development and progression of CAD and subsequent MI. The systemic inflammation from periodontal infections, particularly the elevated levels of CRP and pro-inflammatory cytokines, is associated with an increased risk of atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction. Inflammation is a key factor in the rupture of atherosclerotic plaques, which can lead to the formation of blood clots that block blood flow to the heart. Oral bacteria may influence immune responses in ways that may contribute to myocardial infarction. The presence of oral bacteria can promote platelet aggregation (clot formation) and endothelial dysfunction, both of which play important roles in the pathogenesis of MI. Some oral bacteria are capable of interacting with platelets, increasing their activation and causing blood clots to form more easily, potentially leading to MI. Periodontal disease and the bacterial infections associated with oral biofilm can also increase oxidative stress in the body which promotes lipid oxidation, a key step in the development of atherosclerosis. The oxidation of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol leads to the formation of foam cells and the development of plaques in arterial walls, increasing the likelihood of plaque rupture and MI. The link between oral biofilm, the accumulation of bacteria on the teeth and gums, and stroke has been a growing area of research. Studies suggest that oral biofilm, can be a risk factor for stroke, especially ischemic stroke, through mechanisms such as systemic inflammation, bacterial translocation, and the promotion of atherosclerosis and endothelial dysfunction. The mechanisms linking oral health to stroke include systemic inflammation, bacterial translocation, endothelial dysfunction, platelet activation, and increased oxidative stress which can all contribute to the development of atherosclerosis in the cerebral arteries and increase the risk of stroke. Maintaining good oral hygiene and treating periodontal disease may reduce the risk of stroke by minimizing inflammation and bacterial burden. The link between oral biofilm and endocarditis has been extensively studied, particularly the role of periodontal pathogens in bacteremia, and may potentially infect heart valves. Once in the bloodstream, oral bacteria can adhere to heart valves, especially in individuals with pre-existing heart conditions. The surface of heart valves offers a niche for bacteria to bind to, which is crucial for the development of infective endocarditis. Bacterial adhesion to heart tissue is facilitated by surface proteins on the bacteria that interact with components of the endothelial cells in the heart. The immune response can cause further damage to the heart valves, leading to the development of infective endocarditis. Thus, interaction between oral bacteria and the host immune system is an essential factor in the progression of endocarditis and can play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of infective endocarditis.

How can oral biofilms be managed?

Biofilm management involves treatment by a dentist to identify periodontal disease, manage the disease process, and return the periodontal tissue to a healthier normal state. Improved patient homecare to keep biofilm levels down is suggested to prevent periodontal disease resurgence and the associated systemic effects. Mechanical debridement of the periodontal pocket is unable to remove all of the biofilm as toothbrushes are poorly effective, more than 4 mm subgingival, even under the best efforts of the patient. Re-growth of the biofilm occurs within three hours resulting in a four-fold (400%) increase in biofilm mass. Homecare is compromised as the toothbrush bristles are unable to extend more than 3–4 mm into the pocket and are unable to mechanically contact the biofilm located at deeper depths. A similar problem was observed with oral irrigators (ie. Waterpik) as they do not allow irrigation to the bottom of the pockets as well. The sulcular environment is difficult for most patients to reach with brushing and flossing, making it impossible to control oral biofilms by mechanical means alone as the bacteria grow and replicate rapidly. Post-cleaning biofilm redevelopment is more rapid and complex, exceeding pre-cleaning levels within two days. Chlorhexidine oral rinses have been reported to have an effect on young biofilms, but the bacteria in mature biofilms and nutrient-limited biofilms have shown resistance to its effects. Chlorine dioxide has been demonstrated as an effective oral rinse that functionally debrides the biofilm slime matrix and bacterial cell walls, essentially peeling the biofilm back layer by layer. Chlorine dioxide has not been reported to have any negative effects, either dentally or systemically, and is safe for daily use in patients. Stabilized chlorine dioxide (Cloralstan) has been reported in the literature to reduce both plaque and gingival indices and bacterial counts in the oral cavity similar to other routinely used oral rinses. As bacteria embedded in the biofilm are up to 1000-fold more resistant to antibiotics than planktonic bacteria. The use of antibiotics either systemically or in oral rinses and site application has demonstrated to be unable to eliminate or manage the biofilm bacteria adequately. This has implications both with natural teeth and periodontal issues developing around dental implants, leading to peri-implantitis. Prevention in patients with current cardiac issues should be managed with premedication with an appropriate antibiotic prior to any dental treatment to prevent seeding of the oral bacteria systemically, which may worsen any present cardiac issues. Those patients should also be educated as those with other systemic health issues, as outlined in the connection between their oral health and their general (systemic) issues and addressing these issues will aid in improving overall health.

Conclusion:

Oral biofilm is recognized as a much more complex material then previously understood that functions through the coordination of bacteria within a protective slime matrix. Extensive data and research have demonstrated that oral biofilms causing periodontal disease have distant systemic effects including cardiac related, which is supported in the literature. Although, the absence of oral bleeding on probing or when brushing does not rule out the presence of a periodontal condition or oral biofilm in the gingival sulcus, a dental evaluation is recommended to eliminate any potential systemic effects from any oral biofilm present. Additionally, instructions need to be given to the patient to improve their daily homecare to aid them in managing their oral biofilm that may be present. Frequently, there is a lack of coordination between the physician and dentist in the management of oral biofilms and any periodontal disease that can be present. The physician is in a unique position and is often the first healthcare provider to see the patient and manage their systemic issues. The patients seen by the primary care physician or medical specialist who are being treated for any of the systemic conditions should be referred to the patient’s dentist to evaluate and treat any periodontal disease present to improve treatment results of the whole-body health. Those patients with systemic conditions that do not respond to medical treatment can benefit from dental care to reduce the bacteria in the biofilm and their inflammatory products.

References:

- Loos BG. Systemic effects of periodontitis. Int J Dent Hyg. 2006;4(suppl 1):34-38; discussion 50-52. https://www.ada.org/resources/research/science-and-research-institute/oral-health-topics/periodontitis

- Hajishengallis G, Chavakis T. Local and systemic mechanisms linking periodontal disease and inflammatory comorbidities. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021 Jul;21(7):426-440. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-00488-6. Epub 2021 Jan 28. PMID: 33510490; PMCID: PMC7841384.

- Sintim HO, Gürsoy UK. Biofilms as “Connectors” for Oral and Systems Medicine: A New Opportunity for Biomarkers, Molecular Targets, and Bacterial Eradication. OMICS. 2016 Jan;20(1):3-11. doi: 10.1089/omi.2015.0146. Epub 2015 Nov 19. PMID: 26583256; PMCID: PMC4739346.

- Marsh PD: Dental plaque as a microbial biofilm. Caries Res. 2004 May-Jun; 38(3):204-11.

- Socransky SS, Haffajee AD: Dental biofilms: difficult therapeutic targets. Periodontol 2000. 2002; 28():12-55.

- Kanwar I, Sah AK, Suresh PK. Biofilm-mediated Antibiotic-resistant Oral Bacterial Infections: Mechanism and Combat Strategies. Curr Pharm Des. 2017;23(14):2084-2095. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666161124154549. PMID: 27890003.

- van Steenbergen TJ, van Winkelhoff AJ, de Graaff J: Pathogenic synergy: mixed infections in the oral cavity. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1984; 50(5-6):789-98.

- Gilbert P, Maira-Litran T, McBain AJ, Rickard AH, Whyte FW: The physiology and collective recalcitrance of microbial biofilm communities. Adv Microb Physiol. 2002; 46():202-56.

- Kouidhi B, Al Qurashi YM, Chaieb K. Drug resistance of bacterial dental biofilm and the potential use of natural compounds as alternative for prevention and treatment. Microb Pathog. 2015 Mar;80:39-49. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2015.02.007. Epub 2015 Feb 21. PMID: 25708507.

- Marcinkiewicz J, Strus M, Pasich E. Antibiotic resistance: a “dark side” of biofilm-associated chronic infections. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2013;123(6):309-13. PMID: 23828150.

- Huang R, Li M, Gregory RL. Bacterial interactions in dental biofilm. Virulence. 2011 Sep-Oct;2(5):435-44. doi: 10.4161/viru.2.5.16140. Epub 2011 Sep 1. PMID: 21778817; PMCID: PMC3322631.

- Hojo K, Nagaoka S, Ohshima T, Maeda N.: Bacterial interactions in dental biofilm development. J Dent Res. 2009 Nov;88(11):982-90. doi: 10.1177/0022034509346811.

- Prado MM, Figueiredo N, Pimenta AL, Miranda TS, Feres M, Figueiredo LC, de Almeida J, Bueno-Silva B. Recent Updates on Microbial Biofilms in Periodontitis: An Analysis of In Vitro Biofilm Models. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2022;1373:159-174. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-96881-6_8. PMID: 35612797.

- Wade W, Thompson H, Rybalka A, Vartoukian S.: Uncultured Members of the Oral Microbiome. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2016 Jul;44(7):447-56.

- Prazdnova EV, Gorovtsov AV, Vasilchenko NG, Kulikov MP, Statsenko VN, Bogdanova AA, Refeld AG, Brislavskiy YA, Chistyakov VA, Chikindas ML. Quorum-Sensing Inhibition by Gram-Positive Bacteria. Microorganisms. 2022 Feb 3;10(2):350. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10020350. PMID: 35208805; PMCID: PMC8875677.

- Suntharalingam P, Cvitkovitch DG: Quorum sensing in streptococcal biofilm formation. Trends Microbiol. 2005 Jan; 13(1):3-6.

- Kolaczkowska E, Kubes P.: Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nature Review 2013(13):159-175

- Kumar BP, Khaitan T, Ramaswamy P, Sreenivasulu P, Uday G, Velugubantla RG. Association of chronic periodontitis with white blood cell and platelet count – A Case Control Study. J Clin Exp Dent. 2014 Jul 1;6(3):e214-7. doi: 10.4317/jced.51292. PMID: 25136419; PMCID: PMC4134847.

- http://medicalxpress.com/news/2013-04-white-blood-cell-enzymecontributes.html

- Al-Rasheed A. Elevation of white blood cells and platelet counts in patients having chronic periodontitis. Saudi Dent J. 2012 Jan;24(1):17-21. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2011.10.006. Epub 2011 Dec 2. PMID: 23960523; PMCID: PMC3723072.

- Marsh PD, Featherstone A, McKee AS, et al.: A microbiological study of early caries of approximal surfaces in schoolchildren. J Dent Res. 1989 Jul; 68(7):1151-4.

- Larsen T, Fiehn NE. Dental biofilm infections – an update. APMIS. 2017 Apr;125(4):376-384. doi: 10.1111/apm.12688. PMID: 28407420.

- Fragkioudakis I, Riggio MP, Apatzidou DA. Understanding the microbial components of periodontal diseases and periodontal treatment-induced microbiological shifts. J Med Microbiol. 2021 Jan;70(1). doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.001247. Epub 2020 Dec 4. PMID: 33295858.

- Marsh, P.D.: Dental plaque as a biofilm and a microbial community – implications for health and disease. BMC Oral Health. 2006. 6(Suppl 1): S14.

- Sbordone, L., Bortolaia, C.: Oral microbial biofilms and plaque-related diseases: microbial communities and their role in the shift from oral health to disease. Clin Oral Invest. 2003. Volume 7. P. 181-188.

- Hua, X, Cook, GS, Costerton, JW, et al.: Intergeneric Communication in Dental Plaque Biofilms. Journal of Bacteriology. 2000. Volume 182. p. 7067-7069.

- Ng HM, Kin LX, Dashper SG, Slakeski N, Butler CA, Reynolds EC. Bacterial interactions in pathogenic subgingival plaque. Microb Pathog. 2016 May;94:60-9. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2015.10.022. Epub 2015 Nov 2.

- Könönen E, et al. “Periodontal pathogens and carotid artery atherosclerosis.” European Journal of Oral Sciences. 2012;120(1):63-68.

- Ganganna A, Subappa A, Bhandari P. Serum migration inhibitory factor levels in periodontal health and disease, its correlation with clinical parameters. Indian J Dent Res. 2020 Nov-Dec;31(6):840-845. doi: 10.4103/ijdr.IJDR_896_18. PMID: 33753651.

- Hajishengallis G. Interconnection of periodontal disease and comorbidities: Evidence, mechanisms, and implications. Periodontol 2000. 2022 Jun;89(1):9-18. doi: 10.1111/prd.12430. Epub 2022 Mar 4. PMID: 35244969; PMCID: PMC9018559.

- Beck J, et al. “Periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease: Epidemiology and possible mechanisms.” Journal of the American Dental Association. 2005;136(12):1626-1636.

- Pussinen PJ, et al. “Oral infections and cardiovascular disease—an update.” Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2007;34(10):1119-1132.

- Beck J, et al. “Periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease: Epidemiology and possible mechanisms.” Journal of the American Dental Association. 2003;134(1):12S-21S.

- Mattila KJ, et al. “Association between dental health and coronary heart disease.” Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 1989;16(6):390-394.

- Genco RJ, et al. “The role of inflammation and immunity in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease.” Journal of Periodontology. 2005;76(11):2108-2118.

- Genco RJ, et al. “The role of inflammation and immunity in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease.” Journal of Periodontology. 2005;76(11):2108-2118.

- Beck J, et al. “Periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease: Epidemiology and possible mechanisms.” Journal of the American Dental Association. 2003;134(1):12S-21S.

- Könönen E, et al. “Periodontal pathogens and carotid artery atherosclerosis.” European Journal of Oral Sciences. 2012;120(1):63-68.

- Genco RJ, et al. “The role of inflammation and immunity in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease.” Journal of Periodontology. 2005;76(11):2108-2118.

- Bangalore S, et al. “Oral hygiene, periodontal disease, and cardiovascular disease.” Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2002;39(3):376-378.

- D’Aiuto F, et al. “Periodontal disease and systemic inflammation: The link to cardiovascular disease.” Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2004;31(8):463-472.

- Miller S, et al. “Oral biofilms and infective endocarditis.” Journal of the American Dental Association. 2006;137(9):1266-1274.

- Palmer, RJ, Caldwell DE.: A flowcell for the study of plaque removal and regrowth. J Micro Methods 1995;24(2):171-82.

- Teles FR, Teles RP, Sachdeo A.: Comparison of microbial changes in early redeveloping biofilms on natural teeth and dentures. J Periodontol. 2012 Sep;83(9):1139-48. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.110506. Epub 2012 Mar 23.

- Teles FR, Teles RP, Uzel NG, et al.: Early microbial succession in redeveloping dental biofilms in periodontal health and disease. J Periodontal Res. 2012 Feb;47(1):95-104. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2011.01409.x. Epub 2011 Sep 5.

- Shen Y, Stojicic S, Haapasalo M.: Antimicrobial efficacy of chlorhexidine against bacteria in biofilms at different stages of development. J Endod. 2011 May;37(5):657-61. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.02.007. Epub 2011 Mar 23.

- Guggenheim B, Meier A.: In vitro effect of chlorhexidine mouth rinses on polyspecies biofilms. Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed. 2011;121(5):432-41.

- Kerémi B, Márta K, Farkas K, et al. Effects of chlorine dioxide on oral hygiene–A systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Pharm Des. 2020;26(25):3015-3025. doi:10.2174/1381612826666200515134450

- Sauer K, Thatcher E, Northey R, Gutierrez AA. Neutral super-oxidised solutions are effective in killing P. aeruginosa biofilms. Biofouling. 2009;25(1):45-54. doi: 10.1080/08927010802441412. PMID: 18846439.

- Kouidhi B, Al Qurashi YM, Chaieb K.: Drug resistance of bacterial dental biofilm and the potential use of natural compounds as alternative for prevention and treatment. Microb Pathog. 2015 Mar;80:39-49. doi:10.1016/j.micpath.2015.02.007. Epub 2015 Feb 21.

- Rams TE, Degener JE, van Winkelhoff AJ.: Antibiotic resistance in human chronic periodontitis microbiota. J Periodontol. 2014 Jan;85(1):160-9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.130142. Epub 2013 May 20.

- Rams TE, Degener JE, van Winkelhoff AJ.: Antibiotic resistance in human peri-implantitis microbiota. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2014 Jan;25(1):82-90. doi: 10.1111/clr.12160. Epub 2013 Apr 2.