Outcomes of Pediatric Dental IV Sedation: Four-Year Review

Outcomes of a mobile paediatric dental intravenous sedation service in primary care: four-year results

Rudi Swart1, Mark G. Robbock2, Pabhen Anand3

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 January 2025

CITATION: SWART, Rudi; ROBACK, Mark G.; ANAND, Prabhleen. Outcomes of a mobile paediatric dental intravenous sedation service in primary care: four-year results. Medical Research Archives, Available at: <https://esmed.org/MRA/mra/article/view/6064>.

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i1.6064

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Background: In 2020 a private mobile paediatric intravenous sedation (IVS) service was established for low-risk children in the south-east of England in line with UK Standards for dental sedation. This study aims to assess the outcomes of this service over a four-year period.

Materials and methods: A retrospective evaluation was carried out, including all paediatric dental patients sedated by the IVS service between the1st October 2020 and 30th September 2024.

Results: A total of 274 sedations were included. The mean age was 8.99 years old. No serious adverse events occurred. Eight patients (2.9%) experienced transient post-sedation nausea/vomiting. A total of 271 patients were successfully sedated, a success rate of 98.9%.

Conclusion: This IVS service has been established successfully, with no serious adverse events observed. Parental feedback was overwhelmingly positive. By utilizing moderate sedation, the IVS service offers paediatric patients a safe, outpatient alternative to general anaesthetic for dental procedures. This service addresses an important gap in dental care for children. Expansion of the IVS program could have a major impact on the waiting lists for general anaesthetic paediatric dental procedures in England.

Article Details

Introduction

Pain and anxiety control is a long-established prerequisite for the provision of dentistry. This has been successfully achieved with behaviour management, sedation and general anaesthetic (GA). Following a series of reports which looked into the number of GA’s being performed and number of deaths in dentistry, on the 1st of January 2001, the United Kingdom (UK) Government implemented an official ban on the administration of general anaesthetics to both adults and children in out-of-hospital settings for dental procedures. This regulatory change resulted in a response by some dental practices to establish intravenous sedation (IVS) services for eligible paediatric patients requiring mild to moderate sedation within National Health Service (NHS)-commissioned, out-of-hospital environments. These dedicated facilities became known as dental sedation referral centres, which routinely provided sedation services for children across all age groups until March 2017. At that time, the Office of the Chief Dental officer for England published “Commissioning Dental Services: Service Standards for Conscious Sedation in a Primary Care Setting,” which revised the guidelines to limit simple, midazolam only, intravenous sedation strictly to children aged 12 and above. Consequently, children under the age of 12 were restricted to receiving inhalation sedation with nitrous oxide in primary care facilities or were required to undergo general anaesthesia in hospital facilities.

These new restrictions significantly curtailed access to dental care for the young population, resulting in increasing NHS waiting lists, exacerbated further by backlogs resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The 2020 Report of the Intercollegiate Advisory Committee on Sedation in Dentistry (IACSD) updated guidelines for dental sedation in the UK, which were originally formulated in 2015. This original stipulated that it was expected that children can only be sedated in facilities “equivalent to an Acute NHS Trust”, but it was not clear what this meant. The 2020 update importantly clarified what additional requirements were necessary to be equivalent, and specifically that facilities needed to be staffed and equipped equivalent to secondary care NHS settings. Following these updates, a mobile IVS service described here was established with all the necessary requirements to treat children under intravenous sedation. They expanded their service from an adult only service to include children in the private sector. This paper will be the first report of the outcomes of this mobile intravenous sedation service for children, 4–16 years of age, in an office-based/primary care setting.

Materials and Methods

This study is a retrospective evaluation of a mobile IVS service. The population comprised of all suitable patients referred for dental treatment under 17 years of age over the four-year period of 1 October 2020 to 30 September 2024. Data was collected retrospectively using patient records and analysed on Excel. Acceptance criteria for the IVS is shown in Table 1.

Table 1: IVS service acceptance criteria for dental treatment under intravenous sedation

(ASA = American Society of Anaesthesiologists, IVS = intravenous sedation)

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Over 20 kg | Under 20 kg |

| Age 4–16 years | Under 4 years old |

| ASA I or II | ASA III and over |

| BMI under 30 | BMI over 30 |

| Complexity of dental treatment suitable for IVS | Allergy to benzodiazepines |

| Fasting for 4 hours, clear fluids 2 hours | Recent upper respiratory infection within 2 weeks |

| Suitable airway for sedation | Obstructive Sleep Apnoea |

Children in the London area who were deemed unsuitable by their dentist for nitrous oxide sedation were referred for treatment under moderate IVS (Table 2).

Table 2: Levels of sedation, adapted from ASA

| Level of sedation | Description |

|---|---|

| Minimal | Retains the patient’s ability to independently and continuously maintain an airway and respond normally to verbal commands. |

| Moderate (conscious) | Drug-induced depression of consciousness during which patients respond purposefully to verbal commands, either alone or accompanied by tactile stimulation. |

| Deep | Drug-induced depression of consciousness which might affect airway and spontaneous ventilation during which patients cannot be easily aroused but respond purposefully following repeated painful stimulation. |

Common reasons for IVS referral are listed in Table 3, however, the specific reason was not always recorded as it was often a combination of these factors.

Table 3: Reasons for dentists referring children for IVS

| Common reasons |

|---|

| Complex dental work |

| Complex patient needs where nitrous oxide not deemed effective |

| Severe anxiety not suitable for nitrous oxide |

| Failed nitrous oxide sedation |

| Non-pharmacological behaviour management has failed |

| On a waiting list for treatment under general anaesthetic |

Developing a paediatric mobile sedation service required the creation of standardized policies, protocols, guidelines and quality metric collection metrics. Policies included compliance with the Care Quality Commission (CQC) and the Standards for Conscious Sedation in the Provision of Dental Care released in 2020 by the Intercollegiate Advisory Committee for Sedation in Dentistry (IACSD).

For a service offered in primary care settings to be considered equivalent to a secondary referral service, immediate availability of advanced airway equipment, emergency ventilatory support and emergency drugs were essential, listed in Table 4. Sedation policies and procedures were followed and described below.

Paediatric emergency algorithms and resources by Resuscitation Council UK were always available in a printed version.

Time met Aldrete discharge criteria

| Time | Percentage | Number of Patients |

|---|---|---|

| Expected (less than one hour after last dose) | 97.1% | 264 |

| Prolonged | 0.4% | 1 |

| Rapid | 2.6% | 7 |

Ten of the 272 children who complied with cannulation needed more than one attempt, which translated to a successful cannulation rate on first attempt of 96.3%.

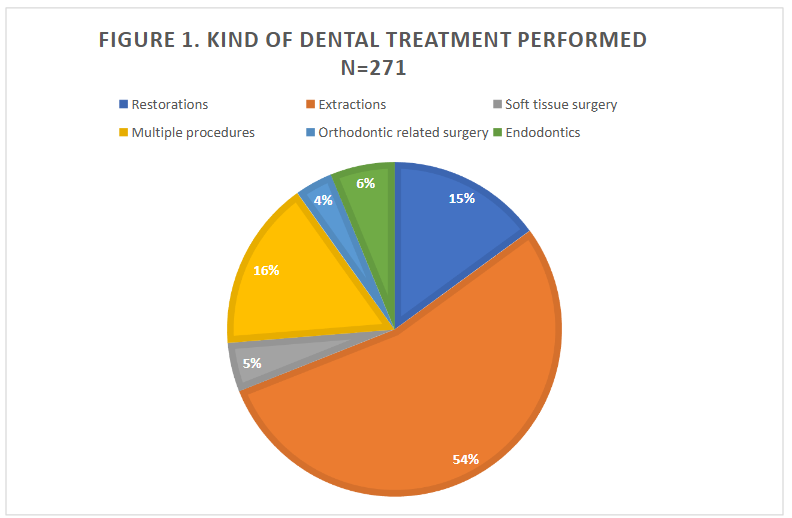

The specific dental treatments undertaken during each sedation can be seen in Figure 1. Most patients were referred for either:

-

Extractions alone (54%)

-

Extractions in combination with restorative treatment (16%)

This accounted for a combined 70% of all referrals. These patients often had combinations of dental phobia, needle phobia, or severe gag reflex associated with anxiety. This information was usually kept by the dentist and did not form part of the sedation practitioner’s records.

Ten of the 272 children who complied with the Aldrete discharge criteria score was at least 9 out of 10. Children who were accompanied by a responsible adult received verbal pre-operative instructions from both the sedation practitioner and the dentist.

Table 7: Adverse events recorded (including TROOPS events) and actions taken

| Adverse event | Results % (n) | Action taken |

|---|---|---|

| Upper airway obstruction and desaturation | 0.02% (5) | Basic airway manoeuvre |

| Vomiting during procedure | 0 | None |

| Vomiting during recovery | 0.02% (6) | No action needed, spontaneously resolved |

| Vomiting after discharge | 0.01% (2) | No action needed, spontaneously resolved |

There were no incidents of intra-operative vomiting, aspiration or acute laryngospasm. No sedation appointments required treatment with advanced airway adjuncts, assisted ventilation or even supplemental oxygen. Advanced airway equipment, emergency ventilatory support, emergency drugs like flumazenil and naloxone, and defibrillators were always immediately available but were never used for any patient in this study.

Of the 271 successful sedations, 241 children completed their course of treatment in a single appointment and 15 children needed two appointments. The children who needed two appointments were for two-stage treatments, mostly root canal treatments.

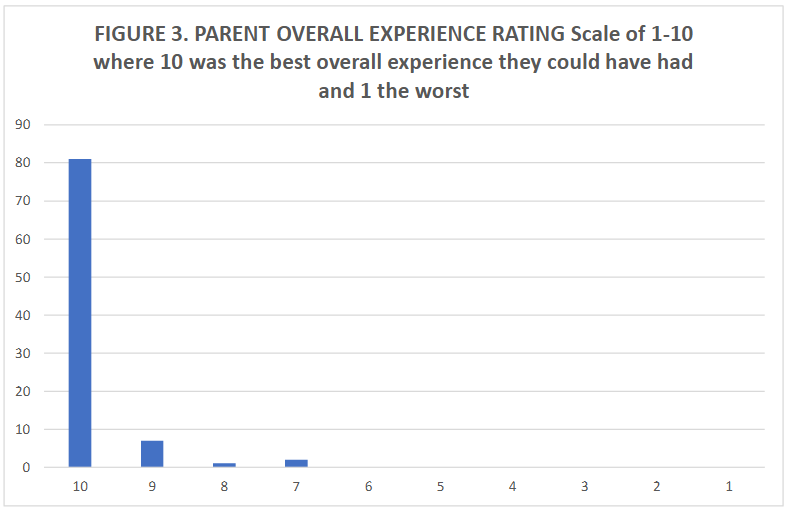

From the feedback forms sent to parents, 81 replied with fully completed feedback forms. This was a response rate of 29.9%. Incomplete feedback forms were omitted. (Results of feedback forms can be seen in Table 8.)

Discussion

The results of this study illustrate that IVS provided to children for dental procedures in the outpatient setting can be successful and safe when administered by experienced and qualified sedation and dental teams working cohesively. Best outcomes are achieved by performing sedation in paediatric-friendly facilities, alongside dentists experienced in treating children, using appropriate equipment, strictly adhering to protocols and choosing patients at low-risk, hence avoiding sedation-related adverse events. It has previously been reported that in addition to anaesthetists, other trained clinicians can safely provide sedation for children given strict adherence to sedation guidelines and this evaluation supports this finding.¹⁶ ¹⁷

The efficacy of sedation in our study was 98.9%. This result showed that with a dedicated team, even the most behaviourally challenging ASA I and II patient cases can be managed out of hospital, as long as careful assessments are carried out in advance of treatment. It also illustrates that by following a protocol as presented here, all treatment can be completed with multi-drug intravenous sedation. This intravenous sedation service provided the much-needed dental treatments to children, needing fewer appointments and avoiding the need for GA.

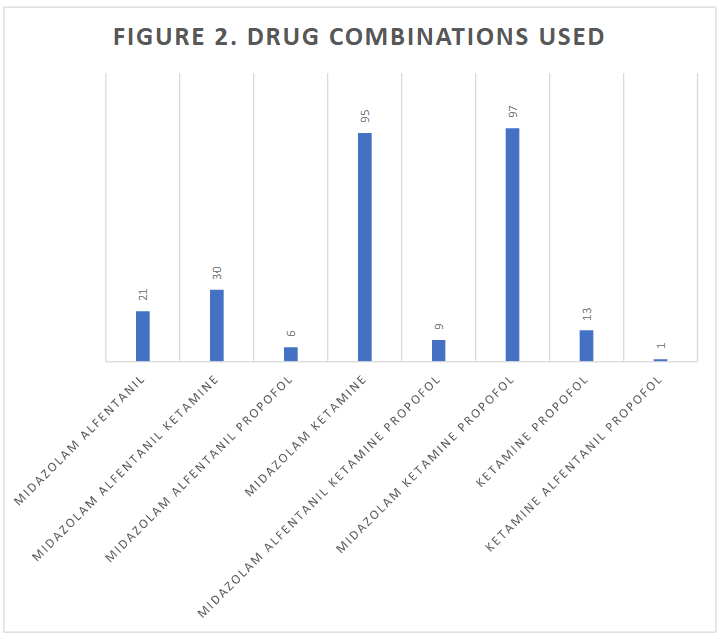

Several sedative drug combinations were used in this study to achieve adequate sedation and analgesia whilst maintaining safety. The most commonly used combination was midazolam and ketamine with or without propofol. While some studies of paediatric sedation outside of the operating room have found an association with increased risk of adverse events when combinations of drugs are used,¹⁸ ¹⁹ this was not the case in our patient cohort where no serious adverse events occurred.

The safety of propofol use in paediatric sedation by clinicians other than anaesthetists has been well documented.²⁰ ²¹ When administered by practitioners of any specialty type who are able to recognize and manage complications requiring advanced airway manoeuvres, propofol has been found to be as safe as other sedatives and combinations.¹⁶ One study of propofol sedation in children found 1 in 65 sedations needing minor airway interventions like chin lifts, which compared with the results in this study.²²

A common concern with children’s sedation in primary care is the occurrence of acute laryngospasm, noted as a rare adverse event with a quoted incidence of 0.4 to 0.7% in procedural sedation.²³ ²⁴ Even though none of the children in this study had such an event, the sample size was not large enough to detect risk with our sedation regimens. The sedation practitioner has however set his age criteria in line with both his experience and an office-based dental anaesthesia study of over 7000 children which showed the risk for adverse events are considerably less in children older than 6 years.²³

A further reason for the chosen age criteria is to obtain co-operation with a child who is at an age that they can understand basic instructions to have their dental treatment completed successfully.

With strict risk assessment criteria adhered to along with close observation intra- and post-operatively this service can potentially be replicated. It needs to be emphasised that appropriate standards need to be met by the surgery, the team and the equipment needed to rescue in case of a medical emergency.

One of the criteria set out by the IACSD for provision of such sedation for young children under 12 years of age is assessment and treatment by teams with skills equivalent to a specialist or consultant in paediatric dentistry and we would endorse this as the purpose of providing sedation was dentistry in the first place. Children receiving this form of sedation were either very anxious or required complex procedures needing IVS. Even though there was no evidence in this study for unplanned repeated sedations, we do need to ensure we avoid the need for repeat sedation in this group of patients. Hospital studies in the past conducted on children having repeat dental GA were strongly linked to not having had an assessment for treatment planning with specialist paediatric dentists.²⁶ ²⁷

Sedations in this study were often performed alongside general dentists or non-paediatric dental specialists who had plenty of experience treating children. The mobile service informed all dentists of the IACSD criteria, but did not enforce this point as parents often insisted that they wanted their child to be treated by their own dentist at their own surgery. This might be something lacking in our service evaluation and criteria which we aim to work towards.

The feedback from parents has illustrated the positive effect sedation can have for children and parents alike, avoiding either long waiting on the national health service or paying to have a general anaesthetic at a private hospital. An added plus point was being able to have treatment carried out locally.

Our study has important limitations. In our cohort of 274 patients who received IV sedation, none experienced serious adverse events such as apnoea, laryngospasm or airway obstruction. These important sedation-related adverse events are rare and a much larger sample size would be required to accurately determine the incidence of these in this IVS service. It should also be noted that it wasn’t the objective of this evaluation to look at the dentistry provided in these treatment episodes and these children were not followed up long term by the sedation service after the initial treatment course set out by the dentist was completed. The results of this study represent outcomes of a single sedation clinician. Larger studies which include a number of sedation providers are needed to demonstrate generalizability of these results.

Conclusion

In this mobile paediatric dental IVS service for children in primary care, rigorously designed to support safe practice, sedation was provided effectively with minimal adverse events. With excellent parental feedback and the absence of serious interventions or complications this IVS service was successful.

The continuation of primary care IVS service is however dependent on national UK guidelines for dental sedation in the UK. Until guidance changes, further auditing of patient data in this practice will continue. It is suggested that other centres engaging in paediatric dental sedation in primary care should also share their results, as currently there is limited data available.

It is further noted that there is a lack of adequate training opportunities for non-anaesthetist physicians in the UK if they would be interested in offering moderate sedation to low-risk children for dental treatment. There are examples of excellent paediatric sedation conferences and training courses offered worldwide. Paediatric sedation training is available in the United States²⁶ ²⁷ and in Europe²⁸ ²⁹. If such training programmes are replicated with additional criteria such as case logbooks described in IACSD Guidelines, this can be a service that can be expanded in the UK to alleviate pressure on the national waiting lists for dental general anaesthetics.

Conflict of Interest:

None

Acknowledgements:

None

References

1. Clincial guide for dental anxiery management. Updated 17 January 2023. Accessed December 2, 2024.

https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/clinical-guide-for-dental-anxiety-management/

2. Landes DP. The provision of general anaesthesia in dental practice, an end which had to come? British Dental Journal ; volume 192, issue 3, page 129-131 ; ISSN 0007-0610 1476-5373. January 2002. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.4801313

3. NHS England’s Office of Chief Dental Officer England published Commissioning Dental Services: Service standards for Conscious Sedation in a primary care setting. Updated 2017. Accessed November 1, 2024.

http://www.saad.org.uk/Documents/dental_commissioning_guide_service_standards_conscious_sedation.pdf

4. Ministers need to act as COVID sees child tooth extractions backlog surge. British Dental Journal. 2022;232(10):679. doi:10.1038/s41415-022-4318-3

5. Intercollegiate Advisory Committee for Sedation in Dentistry. Standards for conscious sedation in the provision of dental care. Updated 2020. Accessed November 1, 2024.

https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/dental-faculties/fds/publications-guidelines/standards-for-conscious-sedation-in-the-provision-of-dental-care-and-accreditation/

6. American Society of Anesthesiologists: Statement on Continuum of Depth of Sedation: Definition of General Anesthesia and Levels of Sedation/Analgesia. Accessed November 1, 2024.

https://www.asahq.org/standards-and-practice-parameters/statement-on-continuum-of-depth-of-sedation-definition-of-general-anesthesia-and-levels-of-sedation-analgesia

7. Care Quality Commission: Dental mythbuster 10: Safe and effective conscious sedation. Updated July 3, 2023. Accessed November 1, 2024.

https://www.cqc.org.uk/guidance-providers/dentists/dental-mythbuster-10-safe-effective-conscious-sedation

8. Resuscitation Council UK: Paediatric emergency algorithms and resources updated March 2024. Updated March 2024. Accessed November 1, 20204. https://www.resus.org.uk/sites/default/files/2024-03/RCUK%20Paediatric%20emergency%20algortihms%20and%20resources%20Mar%2024%20V2.2.pdf

9. Resus Council UK: EPALS (European Paediatric Advanced Life Support) Course. Accessed November 1, 2024.

https://www.resus.org.uk/training-courses/paediatric-life-support/epals-european-paediatric-advanced-life-support

10. Resus Council UK: ALS: 2 Day Course (Advanced Life Support) Course. Accessed November 1, 2024.

https://www.resus.org.uk/training-courses/adult-life-support/als-2-day-course-advanced-life-support

11. Resus Council UK: PILS (Paediatric Immediate Life Support) Course. Accessed November 1, 2024. https://www.resus.org.uk/training-courses/paediatric-life-support/pils-paediatric-immediate-life-support

12. Lozano-Díaz D, Valdivielso Serna A, Garrido Palomo R, Arias-Arias Á, Tárraga López PJ, Martínez Gutiérrez A. Validation of the Ramsay scale for invasive procedures under deep sedation in pediatrics. Paediatric anaesthesia. 2021;31 (10):1097-1104. doi:10.1111/pan.14248

13. Aldrete JA. The post-anesthesia recovery score revisited. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia ; volume 7, issue 1, page 89-91 ; ISSN 0952-8180. January 1995. doi:10.1016/0952-8180(94)00001-k

14. Roback MG, Green SM, Andolfatto G, Leroy PL, Mason KP. Tracking and Reporting Outcomes Of Procedural Sedation (TROOPS): Standardized Quality Improvement and Research Tools from the International Committee for the Advancement of Procedural Sedation. British journal of anaesthesia. 2018;120(1):164-172. doi:10.1016/j.bja.2017.08.004

15. General Medical Council: Guidance for Appraisers. Accessed November 1, 2024.

https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/guidance-for-appraisers—pms-45189197.pdf

16. Couloures KG, Beach M, Cravero JP, Monroe KK, Hertzog JH. Impact of provider specialty on pediatric procedural sedation complication rates. Pediatrics. 2011;127(5):e1154-e1160.

doi:10.1542/peds.2010-2960

17. Smallman B. Pediatric sedation: can it be safely performed by non-anesthesiologists? CURRENT OPINION IN ANAESTHESIOLOGY. 2002;15(4):455-460. Accessed December 2, 2024. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=2d9bd699-9270-3446-a9c5-beaceeda3deb

18. Cote CJ, Karl HW, Notterman DA, Weinberg JA, McCloskey C. Adverse Sedation Events in Pediatrics: Analysis of Medications Used for Sedation. PEDIATRICS -SPRINGFIELD-. 2000;106(41):633-644. Accessed December 2, 2024. https://research.ebsco.com/link

19. Bhatt M, Johnson DW, Chan J, et al. Risk Factors for Adverse Events in Emergency Department Procedural Sedation for Children. JAMA pediatrics. 2017;171(10):957-964. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.2135

20. Kamat PP, McCracken CE, Gillespie SE, et al. Pediatric critical care physician-administered procedural sedation using propofol: a report from the Pediatric Sedation Research Consortium Database. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015;16(1):11-20. doi:10.1097/PCC.0000000000000273

21. Grunwell JR, Travers C, Stormorken AG, et al. Pediatric Procedural Sedation Using the Combination of Ketamine and Propofol Outside of the Emergency Department: A Report From the Pediatric Sedation Research Consortium. Pediatric critical care medicine. 2017;18(8):e356-e363. Accessed December 13, 2024.

https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=0a6ca396-946b-3ae9-8e4b-7ad492207b18

22. Cravero JP, Havidich JE. Pediatric sedation – evolution and revolution. PEDIATRIC ANESTHESIA. 2011;21(7):800-809. Accessed December 2, 2024. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=618c749a-f693-370e-b61a-ed3facc0f0df

23. Bellolio MF, Puls HA, Anderson JL, et al. Incidence of adverse events in paediatric procedural sedation in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open ; volume 6, issue 6, page e011384 ; ISSN 2044-6055 2044-6055. January 2016. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011384

24. Cosgrove P, Krauss BS, Cravero JP, Fleegler EW. Predictors of Laryngospasm During 276,832 Episodes of Pediatric Procedural Sedation. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2022;80(6):485-496. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2022.05.002

25. Spera AL, Saxen MA, Yepes JF, Jones JE, Sanders BJ. Office-Based Anesthesia: Safety and Outcomes in Pediatric Dental Patients. Anesthesia progress. 2017;64(3):144-152. doi:10.2344/anpr-64-04-05

26. Lawson J, Owen J, Deery C. How to Minimize Repeat Dental General Anaesthetics. Dent Update. 2017;44(5):387-395. doi:10.12968/denu.2017.44.5.387

27. Kirby J, Walshaw EG, Yesudian G, Deery C. Repeat paediatric dental general anaesthesia at Sheffield Children’s NHS Foundation Trust: a service evaluation. British Dental Journal. 2020;228(4): 255-258. doi:10.1038/s41415-020-1256-9

28. Snow and Sedation Conference. Accessed December 13, 2024. https://snowandsedation.com

29. Society of Pediatric Sedation Provider course. Accessed November 1, 2024.

https://pedsedation.org/offerings/sedation-provider-course/

30. PROSA Pediatric Sedation Provider Course. Accessed November 1, 2024.

https://www.prosaconference.com/pediatric-sedation-provider-course/