Pharmacogenetics of Lead Toxicity: ALAD Insights

Pharmacogenetics of Lead Toxicity

Moussa M. Diawara, PhD1

- Professor, Department of Biology, Colorado State University Pueblo, 2200 Bonforte Blvd, Pueblo, CO 81001

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 January 2025

CITATION: Diawara, MM., 2025. Pharmacogenetics of Lead Toxicity. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(1). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i1.6268

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i1.6268

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Despite the phasing out of leaded gasoline, lead-based paint and leaded plumbing, lead (Pb) remains a public health risk. Toxicity of Pb occurs primarily due to its inhibition of key enzymes in biosynthesis of heme, a compound required for oxygen binding in bloodstream. One of these enzymes is δ-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (ALAD), the main binding ligand for Pb in erythrocytes. The ALAD enzyme is encoded by the ALAD gene. This gene has two co-dominant alleles (ALAD1 and ALAD2), three genotypes (ALAD1-1, ALAD1-2 and ALAD2-2) and dozens of detected single nucleotide polymorphisms. The G to C transversion in nucleotide 177 in ALAD2 is the difference between ALAD1 and ALAD2 genotypes. This mutation changed the enzyme activity and is the reason it is suggested that individuals with the less common ALAD2 allele tend to experience a greater susceptibility to Pb toxicity than individuals with ALAD1. However, the association of ALAD polymorphism with Pb toxicity remained inconclusive when Pb exposure resulted in blood Pb level < 10 μg/dL, though numerous studies showed that blood Pb level > 10 μg/dL compromised heme synthesis, with the ALAD activity inversely correlated with blood Pb. This review suggests that use of specific combinations of ALAD single nucleotide polymorphisms as biomarkers for susceptibility to Pb exposure and toxicity might contribute to a better understanding of Pb association with ALAD polymorphism. Based on evidence reviewed herein, the current blood lead reference value of 3.5 μg/dL should be further reduced to 0 μg/dL.

Keywords: ALAD, gene polymorphism, lead toxicity

INTRODUCTION

Lead (Pb) is a natural chemical element that occurs in the earth’s crust. The phasing out of leaded gasoline in 1996 coupled with the phasing out of lead-based paint and the replacement of leaded plumbing in construction dramatically reduced the public health risks associated with environmental Pb exposure. However, Pb is persistent and remains in the environment due to historical activities such as mining, smelting, and use of lead in paint, gasoline, pipes, solder, and ceramics that date back centuries. Due to occupational exposure and deposits from past industrial activities such as smelting operations that resulted in contamination of land, air and water, Pb remains at great health risks even decades after cessation of these activities.

As a simple chemical element, Pb is not further broken down once in the body, and no studies have shown its biological requirement as a micronutrient. Population exposure to Pb occurs mainly through inhalation and ingestion, and through the skin to a lesser extent. Regardless of the route of exposure, nearly every organ and organ system of the human body can be adversely affected by Pb, and no exposure level has proven to be safe for Pb, especially in children. This broad range toxicological profile of Pb may be explained by the fact that one of its main targets is the hematopoietic organ system. Blood lead (BPb) is reported to have a half-life of 30 days and is the primary biomarker used to screen for environmental Pb exposure in children because it scores for more recent exposure than Pb in bones. However, the Pb that is deposited in multiple bone sites accounts for 90-95% of the total body Pb burden in adults and this Pb can have a recirculating half-life of 20-25 years.

Epidemiological studies show that Pb adversely affects the central nervous system in both children and adults, the reproductive system, the immune system, the musculoskeletal system, the endocrine system, the gastrointestinal system, the respiratory system, the cardiovascular system, the hepatic function, the ocular function, as well as growth and development. Exposure to Pb has also been linked to cerebral edema and encephalopathy, anemia, hypertension, kidney damage, and to various types of cancer. However, the impacts of Pb on the central nervous, especially in children, have been the most widely reported concerns. The effects of Pb on the nervous system are expressed as decreased cognitive function, learning deficits, neuropathy and encephalopathy at even low doses, in both children and adults. It has also been reported that Pb causes oxidative stress through the reduction of antioxidants and production of reactive oxygen species, and it disrupts calcium homeostasis, ion transport, mitochondrial and protein functions in the cell; these can all lead to apoptotic cell death. The adverse effects can lead to seizures, coma, and even death.

This broad toxicity of Pb has caused the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to consistently update the blood lead reference value (BLRV), which was decreased from 60 micrograms of Pb per deciliter of blood (μg/dL) in 1960 to 40 μg/dL in 1970, 30 μg/dL in 1975, 25 μg/dL in 1985, 10 μg/dL in 1991, and 5 μg/dL in 2012 in order to minimize health risks associated with exposure to Pb sources. On May 2021, the Lead Exposure and Prevention Advisory Committee further recommended the use of the 3.5 μg/dL BLRV by the CDC based on 2015-2016 and 2017-2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. As a result of these regulations, the percentages of U.S. children aged 1-5 years with the BLRV of 5 µg/dL declined from 99.8% in 1976-1980 to 33.2% in 1988-1991, 20.9% in 1991-1994, 8.6% in 1999-2002, 4.1% in 2003-2006, and 2.6% in 2007-2010. The current percentage of U.S. children with the BPb over the new 3.5 μg/dL BLRV is 2.5%. Yet, Pb remains a big threat to public health due to high level occupational exposure as well as various low level environmental contacts. To get a better understanding of the factors influencing BPb in exposed populations, this review examines the pharmacogenetics of Pb toxicity and its implication for health risks.

TOXICOKINETICS OF LEAD

Exposure to Pb or any other xenobiotic (foreign to life chemical) triggers a series of toxicokinetic reactions in the body that include the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of the chemical (ADME). The ADME impacts the concentration of the xenobiotic in various tissues and organs over time. Toxicokinetics is also referred to as pharmacokinetics when dealing with medical drugs. Toxicodynamics (also known as pharmacodynamics for medical drugs) describes the dynamic interactions or fate of the xenobiotic in the body. Absorption of Pb occurs primarily through the respiratory and oral routes for both its inorganic and organic forms, in both adults and children. The toxicokinetics and pharmacokinetics of inorganic Pb all depend on the dose ingested, the age of the exposed population (children being at greater risks than adults), the species and particle size of Pb ingested. Nutritional status, especially the presence of food in the gastrointestinal track, has been shown to decrease toxicity of Pb through reduced absorption. The Pb in the body is primarily excreted by kidney clearance. Once it is absorbed by the body, Pb is distributed in the bloodstream, soft tissues (such as the brain, heart, liver, and muscles), and in mineralizing bone and dentin tissues.

The toxicokinetics of a xenobiotic may be assessed by its plasma concentration and its phase 1 and phase 2 metabolites over time. Phase 1 reactions involve oxidation, reduction and hydrolysis by CYP450 enzymes, while phase 2 reactions are known as conjugations with glucuronic acid, sulfonates, glutathione and amino acids, and these reactions involve a wide range of enzymes named transferases. Both the phase 1 and phase 2 reactions are aimed at increasing water solubility and subsequent excretion of the xenobiotic from the body. Heavy metals such as Pb are directly eliminated or sequestrated, or they undergo biomethylation, biomineralization, or binding to metallothionein or other ligands prior to elimination or sequestration. Although it has been reported that Pb can be biomethylated to an organic compound, the evidence is limited and the chemical process is not well described. There are some proteins analogous to metallothionein that bind Pb in the brain, erythrocytes, liver, lung and kidney. As discussed in the next section, Pb metabolism involves complexing with intracellular and extracellular protein and nonprotein ligands. Gonick provides a comprehensive review of Pb-binding proteins in various organs including the kidney, brain, liver, intestine, and lung during studies involving laboratory animals as well as in human subjects.

Both the toxicokinetics and toxicodynamics of Pb may be influenced by the genetic predisposition of exposed populations. Pharmacogenetics is the study of how the presence of two or more variants of a specific gene (polymorphism) in different individuals impacts their reactions to xenobiotics. The δ-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (ALAD) enzyme is the main binding protein for Pb in the human bloodstream and also plays a key role in the synthesis of heme, an important component of hemoglobin. This review focuses on the epidemiological studies of the ALAD gene polymorphism and the implications of this polymorphism for Pb-induced pathogenicity.

BLOOD LEAD SEQUESTERING PROTEINS

About 99% of the Pb that reaches the bloodstream is bound to erythrocytes and 1% to plasma. The main Pb binding protein in blood was initially thought to be hemoglobin. However, this hypothesis was later dismissed when subsequent research showed that the low molecular mass (240 kDA) δ-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (ALAD) and two other low molecular weight proteins were the binding ligands for Pb in erythrocytes. These three proteins were indicators of environmental Pb exposure and related toxicity. ALAD has the strongest affinity with 35–81% of blood Pb and has been the main subject of research aimed at examining gene-Pb interactions. About 80% of the bloodstream Pb is bound to the ALAD enzyme alone. The other two proteins were one protein of 45 kDA with 12-36% of blood Pb and the other of approximately 10 kDA, with less than 1% of blood Pb. These three proteins can impact Pb toxicity by sequestering it; some studies suggest that this sequestration may be protective against Pb toxicity, while other studies report the exact opposite effect. At any rate, the ALAD protein is so important that hereditary deficiency of this protein has been reported to cause acute Pb poisoning in a patient.

RELATIONSHIP OF δ-AMINOLEVULINIC ACID DEHYDRATASE GENE POLYMORPHISM AND LEAD TOXICITY

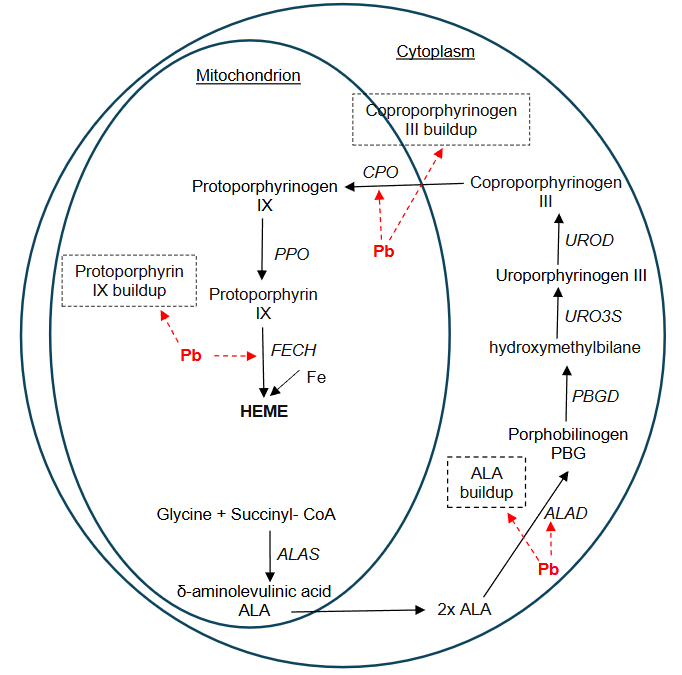

The hematopoietic system is the organ system involved in the production of blood cells in the body. Epidemiological studies show that this organ system is a target of Pb toxicity, making this heavy metal a serious health threat. A cross-sectional study of 855 preschool children 3-7 years of age showed a significant relationship between erythrocyte Pb and hemoglobin levels, leading to the conclusion that erythrocytes were a primary target of Pb toxicity. A review article reported that chronic background as well as occupational Pb exposure can result in altered heme synthesis, anemia and/or decreased measures of hemoglobin, decreased platelet count, decreased serum erythropoietin and altered red blood cell function. The Pb toxicity occurs primarily due to inhibition of key enzymes in the biosynthesis of heme. Heme is an organic, nonprotein portion of hemoglobin and some other biological molecules. Heme contains iron and is required for oxygen binding in the bloodstream. During the first step in heme synthesis, the δ-aminolevulinic acid synthase (ALAS) catalyzes the reaction between glycine and succinyl CoA by condensing them to yield δ-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) in the mitochondrion. Research showed that Pb does not affect the inhibitory effect of ALA synthase. The second step of heme synthesis involves the formation of porphobilinogen (PBG) from two molecules of ALA; this reaction occurs in the cytoplasm and is catalyzed by ALAD, also known as porphobilinogen synthase. Four molecules of PBG align to form linear hydroxymethylbilane (HMB), a reaction enabled by porphobilinogen deaminase (PBGD), also known as hydroxymethylbilane synthase. The linear HMB molecule closes to form uroporphyrinogen III during a reaction catalyzed by uroporphyrinogen-III synthase (URO3S). The uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase (UROD) causes the conversion of uroporphyrinogen III into coproporphyrinogen III in the cytoplasm. Coproporphyrinogen III is transported back into the mitochondria where it is decarboxylated to produce protoporphyrinogen IX under the action of coproporphyrinogen oxidase (CPO). Protoporphyrinogen oxidase (PPO) converts protoporphyrinogen IX to protoporphyrin IX. Finally, a Fe ion is inserted into protoporphyrin IX by the action of the enzyme ferrochelatase (FECH) to yield heme. The mechanism of Pb toxicity during heme synthesis is due to its disruption of this pathway in both the mitochondrion and the cytoplasm by inhibiting three key enzymes: ALAD, CPO and FECH (Figure 1). The ALAD is a homomultimeric enzyme with eight identical protein subunits, each with a Z++ active site. The enzyme is encoded by the ALAD gene, which is located on chromosome 9q34. Lead usually binds to the ALAD enzyme and displaces the zinc; this inactivation of ALAD results in the pathogenesis of Pb poisoning. In addition, Pb also strongly inhibits both CPO and FECH, which are all involved in the final steps of heme synthesis. However, ALAD has the greatest affinity for Pb and has been used as a biomarker of Pb exposure and for the determination of Pb intoxication. Research shows that Pb is such a potent intoxicant that a BPb level as low as 15 pg/dL has been reported to cause 50% inhibition of ALAD activity.

The ALAD gene has two co-dominant alleles, ALAD1 and ALAD2, and thus three genotypes: ALAD1-1, ALAD1-2 and ALAD2-2. The gene has dozens of detected single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) although only a few SNPs have been studied. Yet, when it comes to gene-Pb interactions, the SNP most widely examined has been rs1800435, the G to C transversion in nucleotide 177 in ALAD2, which is the difference between ALAD1 and ALAD2. The SNP rs1800435 is also known as ALAD1 for the common allele and ALAD2 for the variant. This mutation resulted in coding for asparagine (a neutral amino acid) instead of lysine (a positively charged amino acid) at residue 59, changing the enzyme activity. This is the reason it is suggested that individuals with the ALAD2 allele produce enzymes that have a greater electronegativity and binding capacity for Pb and tend to experience greater susceptibility to Pb toxicity than individuals with the ALAD1 allele. The two alleles of the ALAD gene have different frequencies in humans. The frequency of the ALAD2 allele is reported to be lower (10-20%) than that of the ALAD1 (80-90%) in non-Hispanic white population and even much lower in African and Asian populations. The Third US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) from 1988–1994 found that 13.6% of the total population, 15.6% of non-Hispanic whites, 2.6% of non-Hispanic blacks, and 8.8% of Mexican Americans are ALAD2 carriers. However, these frequencies vary depending on the geographical area and occupation of the study populations. The differential allelic distribution coupled with variations in population exposure made it hard for researchers to establish a strong association between BPb and ALAD genetic polymorphism, and the reports from epidemiological studies are sometimes conflicting.

Some of the earlier epidemiological studies by Ziemsen et al. examined the link between ALAD and BPb in 202 German adult males occupationally exposed to Pb. The subjects that were Pb workers had a 50 % decrease of ALAD activity in comparison to controls; and this decrease was phenotype dependent on the order of ALAD1-1, ALAD2-1 and ALAD2-2. The BPb levels showed a reverse trend. Almost concurrently, Astrin et al. also tested 1,051 New York children who were environmentally exposed to Pb. The study found that subjects with one or two copies of the ALAD2 allele (ALAD1-2 or ALAD2-2) had higher BPb than subjects who were homozygous for the ALAD1 allele (ALAD1-1). Wetmur et al. also examined 202 Pb workers in Germany and 1278 New York children with elevated free protoporphyrin levels due to environmental Pb exposure. The authors found that BPb was 9 to 11 μg/dL higher in ALAD1-2/2-2 individuals than the ALAD1-1 homozygous, and concluded a more effective Pb binding and susceptibility to poisoning by ALAD2 than ALAD1. Fleming et al. examined 381 Pb smelter workers, many with a long history of exposure, and reported a more efficient uptake of Pb from the blood into the bone for subjects with ALAD1-1 compared to the ALAD1-2/2-2, further confirming the impact of ALAD on Pb toxicokinetics.

Later studies also reported contradictory findings for the association between a person’s ALAD genotype and BPb. A cross-sectional study examined 120 male workers from China, India and Malaysia, exposed to low to medium Pb levels (average of 22.1 μg/dL BLb), to determine the association between ALAD1 and ALAD2 genotypes and neurobehavioral functions. No differences were found between ALAD1-1 and ALAD1-2/2-2 carriers. However, urinary buildup of ALA was significantly higher in subjects with the ALAD1 allele than the ALAD2, and the ALAD1 carriers had significantly lower neurobehavioral scores than the ALAD1-2/2-2 carriers. The authors suggested that ALAD2 genotype may have protective effects against Pb-induced neurotoxicity. Another study of 691 construction workers with an average BPb of 7.78 μg/dL showed no difference in BPb of ALAD2 carriers compared to ALAD1 homozygous. Hu et al. also observed no association between ALAD genotype and BPb in a Boston, Massachusetts population of 726 men with no environmental Pb exposure, and with BPb varying between 5.7 μg/dL (for ALAD1-2/2-2 carriers) and 6.4 μg/dL (for ALAD1-1 carriers). Yet, Pérez-Bravo et al. tested 93 children from schools near a Pb-contaminated area in Chile and observed that children carriers of ALAD-2 allele tend to have higher BPb (range 6 to 27 μg/dL) than ALAD1-1 children (range 0 to 26 μg/dL); however, the differences were not statistically significant. A smaller study examined BPb inhibition of ALAD among 39 urban male adolescents in India. The subjects BPb varied between 4.62-18.64 μg/dL and were categorized in two groups: those with BPb < 10 μg/dL and those with BPb > 10 μg/dL. The study found a significantly higher inhibition of ALAD activity in subjects with BPb > 10 μg/dL compared to those with BPb < 10 μg/dL.

Basically, since the availability of the first literature on the association of Pb-induced toxicity and the ALAD gene polymorphism, nearly 40 years ago, researchers have yet to reach strong conclusions about the role of the two alleles of the gene, especially at low Pb exposure level. Some studies have reported reduced bioavailability of Pb in ALAD2 carriers, resulting in protective effects against toxicity to target organs, while other findings lead to the opposite conclusion. A review published by Kelada et al. in 2001 argued that the available data were conflicting and that susceptibility to Pb pathogenicity was not linked with ALAD polymorphism at background exposure levels. A following meta-analysis by Scinicariello et al. in 2007 concluded that occupationally Pb exposed adults who are ALAD1-2 or ALAD2-2 carriers had higher BPb than those who carry ALAD1-1. A positive correlation was established between Pb exposure and rs1800435 polymorphism in the ALAD gene. However, consistently with the 2001 review, the 2007 report also concluded that no effect of ALAD on BPb was observed at environmental exposure resulting in BPb < 10 µg/dL.

Research on the genetic polymorphism in ALAD since the publication of the above two meta-analysis reviews follows the same basic trend in the lack of consistency; however, the new evidence tends to support that ALAD2 carriers have a greater Pb binding ability and potential susceptibility than ALAD1 carriers, sometimes even at low level exposure. Wang et al. found a reverse association between ALAD activity and BPb in people with low BPb (6.7 md/dL) in China. A similar finding was reported by Miyaki et al. who tested a non-exposed Japanese population of 101 workers with a mean BPb 3.38 μg/dL and still observed a significant association between ALAD2 genotype and BPb. The NHANES III survey from 1988–1994 examined data from over 6,000 people over 17 years old to determine if ALAD genotype influenced the relationship between blood pressure and BPb. The study found a significant relationship between BPb and the ALAD2 allele among non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic blacks, but not among Mexican Americans. Kayaalti and co-workers examined the relationship between ALAD G177C polymorphism (rs1800435) and placental Pb levels in 97 healthy mothers, 18-41 years old with no history of occupational Pb exposure. The study found a significant correlation between maternal ALAD polymorphism and placental Pb levels; Pb levels for ALAD1-1, ALAD1-2 and ALAD2-2 genotypes were 0.75 μg/dL, 1.18 μg/dL and 1.85 μg/dL, respectively. Au contraire, Yang et al. examined 156 men and women workers exposed to battery Pb and cable Pb in China, and reported that workers with the ALAD1-1 genotype had higher BPb than those with the ALAD1-2 genotype (21.58 μg/dL vs 16.72 μg/dL for battery workers; and 5.76 μg/dL vs 4.97 μg/dL for cable workers, respectively).

Diawara and colleagues tested 231 children living near Pb contaminated old smelters and other parts of the same town in Colorado and found that genetic polymorphisms for ALAD1 or ALAD2 alleles were not associated with children BPb. All the subjects tested had BPb < 10 μg/dL although some children lived near old smelters. These findings are also consistent with other reports that failed to establish association between ALAD polymorphism and BPb < 10 μg/dL. However, Mani et al. reported an association among an adult population at low exposure. They examined 878 adults for the effect of ALAD polymorphism on BPb in India; 561 were occupationally exposed to Pb (BPb range 36.7-53.4 μg/dL) and 317 were not exposed (BPb range 2.9-4.1 μg/dL). The authors found that the ALAD2 allele carriers had higher BPb levels than the ALAD1 homozygous in the population examined, irrespective of Pb exposure level. These findings align with a recent study by Sahu and co-workers who observed 90 pregnant women in India for ALAD polymorphism; 16 with BPb ≥ 5 μg/dL and 74 BPb < 5 μg/dL. The study found that subjects with the ALAD1-2/2-2 genotypes had significantly higher BPb and showed higher DNA damage than those with the ALAD1-1 genotype. The BPb and DNA damage in the infants were positively correlated to those in the mothers. Among the 16 participants with BPb ≥ 5 μg/dL, four had BPb >10 μg/dL, ranging from 11.7-26.89 μg/dL. Clearly, this study shows that the ALAD2 allele is still associated with higher Pb binding than ALAD1 even at lower, non-occupational exposure level.

In addition to the 2016 report by Kayaalti et al., other studies have focused on the relationship between BPb and ALAD G177C rs1800435, the most widely examined SNP for ALAD polymorphism. This G to C transversion in nucleotide 177 in ALAD2 is the difference between ALAD1 and ALAD2. The second two most studied SNPs are rs1139488 (A > G) and rs1805313 (A > G). A number of workers have recently focused their efforts on these SNPs, in an attempt to better understand the ALAD/BPb associations. Palir and colleagues examined the association between ALAD polymorphism (rs1800435, rs1805313, rs1139488, rs818708) and blood Pb effects in 873 Italian women and their newborns at low level Pb exposure. Despite the low maternal peripheral venous blood level of 11.0 ng/g, a clear evidence of low exposure, the authors still observed a positive association between maternal BPb and ALAD rs1139488, and a negative relationship for ALAD rs1800435 and rs1805313. Their study certainly suggested effects of ALAD on Pb kinetics in women and their newborns.

A follow up study by Stajnko and colleagues examined the associations between ten ALAD SNPs with blood Pb (BPb) and urine Pb (UPb) concentrations in 281 adult men between 18-49 years. The test subjects resided in both Pb-contaminated and non-contaminated areas, with a geometric BPb mean of 19.6 μg/dL and a range from 3.86-84.7 μg/dL. The authors used SNP haplotypes, individual SNPs and the combination of two SNPs to examine the potential effect of ALAD polymorphism. The study found no associations for haplotypes. However, the variant alleles of rs1800435 and rs1805312 were linked to a decrease in BPb, while presence of rs1139488 homozygous was associated with an increase in BPb. These findings were consistent with previous observations. The study also observed a significant association with Pb for SNP rs1139488 (A > G), which is closely located to rs1800435. Although this later observation is also consistent with a previous research, it does not align with a study of occupational workers by Rabstein and co-workers who reported a lack of association. Research by Szymańska-Chabowska et al. also examined 101 adult Pb workers and found quite the opposite trend, a higher BPb in the ALAD variant rs113948 carriers. During their study, Stajnko et al. found that the rs1800435-rs1139488 and rs1139488-rs1805313 combinations provided the best explanatory power and the SNPs-Pb associations were determined by exposure level. The study showed that individual SNPs only explain a small fraction of variations in BPb, while combinations of two SNPs can explain a larger proportion of the variability.

CONCLUSION

Research has certainly shown the implication of ALAD polymorphism in Pb bioaccumulation and intoxication; however, it is unclear whether the toxicity is due to Pb sequestration or lack of sequestration, or to other confounding factors that affect both Pb toxicokinetics and toxicodynamics. Onalaja and Claudio proposed two possible scenarios, given the same level of exposure: 1) there is a potential high distribution of Pb in organs such as brain and kidney as a result of increased Pb binding to ALAD (ALAD2 in particular); 2) the high affinity of ALAD2 causes sequestration of Pb in the blood and protect other organs; therefore, ALAD2 carriers will have higher BPb and decreased bone Pb for instance, but could experience less toxicity to brain and kidney compared to ALAD 1-1 carriers. The authors suggested that Pb-induced organ toxicity could be greater in ALAD1-1 carriers despite having lower BPb than ALAD2 carriers. It was recently confirmed that the influence of ALAD2 on BPb was dose-dependent, with Pb in ALAD2>ALAD1 at high exposure and Pb in ALAD2

The impact of ALAD polymorphism on buildup of ALA is also a future research area of interest in understanding the pharmacogenetics of Pb toxicity. When plasma ALA and urinary ALA were examined in 65 Korean lead workers by Sithisarankul et al., it was found that plasma ALA was significantly higher in ALAD1-1 carriers than ALAD2 carriers. This Pb-induced buildup of plasma and urinary ALA is significant, considering that Pb also strongly inhibits two other enzymes involved during heme synthesis: coproporphyrinogen oxidase and ferrochelatase. Research on the implications of buildup of the substrates of these two enzymes (coproporphyrinogen III and protoporphyrin IX, respectively) in blood and other organs is limited. Future investigations on how the upstream Pb-induced inhibition of ALAD affects the next two inhibition steps might help better understand the mechanism of Pb toxicity and its association with ALAD polymorphism. A greater focus on research using specific combinations of ALAD SNPs as biomarkers for the study of genetic susceptibility to Pb exposure and toxicity instead of individual SNPs might also contribute to better understand the impact of ALAD polymorphism on Pb toxicity.

In summary, the contradictions about the role of the ALAD gene polymorphism in Pb pathogenicity might be due mainly to exposure level, although the influence of demographic factors such as age, ethnicity and related genetic as well as epigenetic background, and socio-economic conditions cannot be dismissed. The associations between ALAD gene and BPb are inconclusive at non-occupational, low level of exposure. However, at occupational and other high environmental exposure levels (such as children living in contaminated areas), BPb has been shown to be higher in individuals with ALAD2-1 and ALAD2-2 allelic variants than ALAD1-1 based on the vast majority of epidemiological studies. Due to the ALAD2 sequestration of Pb, making it less bioavailable, studies conflict about the protective effect of this allele against Pb toxicity. The current review is consistent with a 2020 profile of Pb toxicity that found that inhibition of ALAD was observed in only a few studies at Pb exposure resulting in BPb < 10 μg/dL, while numerous studies showed that BPb > 10 μg/dL compromised heme synthesis by inhibiting other enzymes in a dose-dependent manner, with the ALAD activity inversely correlated with BPb. The ALAD-BPb association is further complicated by the fact Pb stored in mineralizing tissues such as the bones has a half-life of 20-25 years, during which the Pb can be recirculated back in the bloodstream; this Pb is hard to account for when scoring for recent exposure.

Finally, as stated earlier, the CDC recently recommended the use of 3.5 μg/dL as BLRV. However, the studies reviewed herein demonstrate that no detectable BPb level is acceptable from population health risk management standpoint. For instance, a report by Sahu and co-workers showed that even a BPb level as low as 0.05 μg/dL in a pregnant mother was detectable in the baby. This is a clear indication that the current BLRV of 3.5 μg/dL should be further reduced to 0 μg/dL.

REFERENCES

- US Energy Information Administration. Gasoline explained History of gasoline https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/gasoline/history-of-gasoline.php. Last updated December 22, 2023. Accessed November 20, 2024

- Schwartz J, Pitcher H. The relationship between gasoline lead and blood lead in the United States. J Off Stat. 1989;5(4):421-431.

- Brody DJ, Pirkle JL, Kramer RA, et al. Blood lead levels in the US population: Phase I of the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III, 1968-1991). J Am Med Assoc. 1994;272(4):277-283. Doi: 10.1001/jama.272.4.277

- Pirkle JL, Kaufmann RB, Brody DJ, et al. Exposure of the U.S. population to lead, 1991-1994. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;106(11):745-750. Doi: 10.1289/ehp.98106745

- Jones RL, Homa DM, Meyer PA, et al. Trends in blood lead levels and blood lead testing among US children aged 1 to 5 years, 1988-2004. Pediat. 2009;123,e376-e385. Doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3608

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). Toxicological profile for lead. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry; 2020. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/TSP/ToxProfiles/ToxProfiles.aspx?id=96&tid=22. Last update August 07, 2020 (Accessed Nov 25, 2024)

- Bergdahl, I.A., Skerfving, S., 2022. Lead, Handbook on the Toxicology of Metals, fifth ed. Elsevier B.V. Doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-822946-0.00036-2.

- Diawara MM, Litt JS, Unis D, et al. Arsenic, cadmium, lead, and mercury in surface soils, Pueblo, Colorado: Implications for population health risk. Environ Geochem Health. 2006;28(4):97-315. Doi: 10.1007/s10653-005-9000-6

- Diawara MM, Shrestha S, Carsella J, Farmer S. Smelting Remains a Public Health Risk Nearly a Century Later: A Case Study in Pueblo, Colorado, USA. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(5):932. Doi: 10.3390/ijerph15050932

- Collin MS, Venkatraman SK, Vijayakumar N, et al. Bioaccumulation of lead (Pb) and its effects on human: A review, Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances. 2022;7,100094,ISSN 2772-4166.

- Landrigan PJ, Gehlbach SH, Rosenblum BF, et al. Epidemic lead absorption near an ore smelter: The role of particulate lead, N Engl J Med. 1975;292(3)123-129. Doi: 10.1056/NEJM197501162920302

- Clark HF, Hausladen DM, Brabander DJ, Urban gardens: Lead exposure, recontamination mechanisms, and implications for remediation design. Environ Res. 2008;107(3):312-319. Doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2008.03.003

- Balachandar R, Bagepally BS, Kalahasthi R, Haridoss M. Blood lead levels and male reproductive hormones: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Toxicology. 2020;443:152574. Doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2020.152574

- Gidlow DA. Lead toxicity. Occup Med (Lond). 2015 Jul;65(5):348-56. Doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqv018. Erratum in: Occup Med (Lond). 2015 Dec;65(9):770. Doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqv170.

- Stajnko A, Palir N, Snoj Tratnik J, et al. Genetic susceptibility to low-level lead exposure in men: Insights from ALAD polymorphisms. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2024 Mar;256:114315. PMID: 38168581. Doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2023.114315

- Mitra P, Sharma S, Purohit P, Sharma P. Clinical and molecular aspects of lead toxicity: An update. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2017;54(7-8):506-528. Doi: 10.1080/10408363.2017.1408562

- Ruckart PZ, Jones RL, Courtney JG, et al. Update of the Blood Lead Reference Value — United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:1509–1512. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7043a4

- Wang X, Bakulski KM, Mukherjee B, Hu H, Park SK. Predicting cumulative lead (Pb) exposure using the Super Learner algorithm. Chemosphere. 2023 Jan;311(Pt 2):137125. Doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.137125

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 2024. CDC Updates Blood Lead Reference Value. https://www.cdc.gov/lead-prevention/php/news-features/updates-blood-lead-reference-value.html Last update April 2024. (Accessed Nov 25, 2024).

- Barry PS, Mossman DB. Lead concentrations in human tissues. Br J Ind Med. 1970;27(4):339-51. Doi: 10.1136/oem.27.4.339

- Rabinowitz MB. Toxicokinetics of bone lead. Environ Health Perspect. 1991;91:33-37. Doi: 10.1289/ehp.919133

- Oliveira S, Aro A, Sparrow D, et al. Season modifies the relationship between bone and blood lead levels: the Normative Aging Study. Arch Environ Health. 2002;57(5):466–472. Doi: 10.1080/00039890209601439

- Wilker E, Korrick S, Nie LH, et al. Longitudinal changes in bone lead levels: the VA normative aging study. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2011;53(8):850–855. Doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31822589a9

- Bellinger D, Leviton A, Waternaux C, Needleman H, Rabinowitz M. Longitudinal analyses of prenatal and postnatal lead exposure and early cognitive development. N Engl J Med. 1987;316(17):1037-43. Doi: 10.1056/NEJM198704233161701

- Needleman HL, Gatsonis CA. Low-level lead exposure and the IQ of children. A meta-analysis of modern studies. JAMA. 1990;263(5):673-8.

- Al-Saleh I, Shinwari N, Nester M, et al. Longitudinal study of prenatal and postnatal lead exposure and early cognitive development in Al-Kharj, Saudi Arabia: a preliminary results of cord blood lead levels. J Trop Pediatr. 2008;54(5):300-7. Doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmn019

- Hu WY, Wu SH, Wang LL, Wang GI, Fan H, Liu ZM. A toxicological and epidemiological study on reproductive functions of male workers exposed to lead. J Hyg Epidemiol Microbiol Immunol. 1992;36(1):25-30.