Professionalism and Gender Identity in Healthcare Ethics

Professionalism and Gender Identity in Health Care

Maurice M. Garcia, MD1 Kimberly S. Topp, PT, PhD, FAAA2*

- Professor, Department of Urology, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California, [email protected](310) 423-4256

- PT, PhD, FAAAProfessor and Chair Emeritus, Department of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Science, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California, [email protected](415) 601-7502

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 June 2025

CITATION: Garcia, M.M., Topp, K.S., 2025. Professionalism and gender identity in health care. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(6). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i6.6598

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i6.6598

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

In this work we discuss the meaning of professionalism, explore examples of tension between professionalism and recent U.S. government Executive Orders, and propose ideas for health care providers and educators to teach by modeling professionalism for future generations. Professionals in health care in the United States strive to adhere to four principles of medical ethics. Beneficence denotes a commitment to promote the wellbeing of others. Nonmaleficence refers to an effort to reduce risk to persons – to do no harm. Autonomy implies making one’s own decisions, and health care professionals strive to facilitate patients’ choices. Justice signifies fairness, and a commitment to treat individuals equally regardless of background. Each health care profession has a defined scope of practice, occupationally controlled education, program accreditation, licensure of graduates, and oversight of practitioners. Professional education includes ethics training and stipulates ongoing ethical practice. Recent Executive Orders and actions in the United States have introduced moral difficulty for health care educators and practitioners. External controls that deny gender identity, oppose gender affirming health care, and restrict programs addressing diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility do not align with the ethical principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy or justice. Beyond care for the individual, directives limiting scientific funding and excluding the large population of persons who identify as transgender or gender diverse will have long term adverse effects on science, health, and health care costs in the United States. Beyond the country’s borders, United States policies are already impacting health care for vulnerable populations. The purpose of this article is to bring awareness of these professionalism issues and to support learners and health care practitioners in their efforts to uphold the four principles of medical ethics.

Keywords

Professionalism, Gender Identity, Health Care, Medical Ethics, Diversity, Equity, Inclusion

THE EUROPEAN SOCIETY OF MEDICINE

Medical Research Archives, Volume 13 Issue 6

COMMENTARY ARTICLE

Introduction

As professionals in health care and higher education, we bring the next generation into the health care professions and prepare learners to serve society in their chosen field. An important component of learners’ preparatory curriculum is an understanding of how the four core non-hierarchical principles of medical ethics: beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice, are the fabric of Western Medicine, and its practice. As practitioners and consumers of health care, our learners confront ethical decisions every day, balancing core respect for persons and personal autonomy with limitations on autonomous choice in health care. Our aim in this work is to explore the tension between professionalism principles and external constraints on professional practice, using the real-world example of U.S. government Executive Orders in the United States. We consider the challenges of respecting the law and others’ perspectives, while at the same time advocating for science and personal choice.

At this moment in history, our professions’ ability to serve individuals and society, and to educate future health care providers, by means that align with the four core principles of medical ethics, is under threat from recent Executive Orders and actions in the United States. Executive Order 14168 (Defending Women From Gender Ideology Extremism and Restoring Biological Truth to the Federal Government), states that “gender identity” cannot be used in place of “sex”, and only two biological sexes are to be recognized. The call by other Executive Orders (Initial Rescissions of Harmful Executive Orders and Actions; Ending Radical and Wasteful Government DEI Programs and Preferencing) to eliminate any efforts to promote diversity and inclusion in medical research, also violates the medical ethics principles of nonmaleficence and justice, as these actively harm vulnerable populations, and are inherently inequitable.

In this treatise, we aim to educate the public and professionals in health care and higher education to become informed consumers of information and decision-makers for themselves and society. This editorial is a personal work and does not necessarily represent the standpoints of our home institutions or the professional societies to which we belong.

Defining a profession and professionalism

The English word profession derives from 15th-century Middle-English and the antecedent medieval Latin word profiteri, for the public acknowledgement that one belongs to an occupation in which they profess to be skilled. In medieval times, professionals belonged to guilds defined by specific ethical and craft-related standards, to which their members professed to adhere. Merriam-Webster defines professionalism as “the conduct, aims, or qualities that characterize or mark a profession or professional person”. Diving deeper into the concept of professionalism, Friedson describes a profession as a kind of occupation, its work, and the knowledge and skill to perform that work. Defining elements of a profession are: 1) an officially recognized body of knowledge and skill, based on abstract concepts and theories, and requiring the exercise of discretion on the part of the professional; 2) an occupationally negotiated division of labor; 3) an occupationally controlled labor market based on training credentials; and 4) an occupationally controlled training program associated within a university and segregated from the ordinary labor market.

As noted, one of Friedson’s defining principles of a profession is an occupationally controlled labor market based on training credentials. As such, graduates of health care professions programs in the United States undertake state board licensure examinations and maintain licensure through regular continuing education and assessment. License examinations test the professional’s knowledge and skills within the occupationally negotiated division of labor. The Federation of State Medical Boards and the Federation of State Boards of Physical Therapy oversee the licensure of medical and physical therapist professionals, respectively. With professionalism, the occupation (or profession) controls the work, in contrast to more routine forms of work in which consumers or managers control and shape practices. In this sense, a profession controls and defines the scope of its own practice, sets its own educational requirements, and teaches incoming new members and practitioners. A profession’s standards determine both the entry requirements for the profession and the requirements for educational programs. The profession also oversees the conduct of its members. An example of a profession’s self-regulation is seen in the Declaration of Professional Responsibility from the American Medical Association. Amongst the nine principles are: #1 Respect human life and the dignity of every individual; #7 Educate the public and polity about present and future threats to the health of humanity; and #8 Advocate for social, economic, educational, and political changes that ameliorate suffering and contribute to human well-being. These example principles align with the principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice. Constraints by forces external to the medical profession that appear to be in conflict with the core principles of medical ethics may induce moral distress in professionals.

Academic programs

Academic programs that educate potential members of the profession align with the mission, vision, and values of the profession’s work. For example, the American Council of Academic Physical Therapy (ACAPT) states that “Member institutions are champions of innovation, inclusion, and inquiry in academic physical therapy”, and envisions “As a respected leader in academic physical therapy, ACAPT will create a shared culture of excellence to improve societal health”. Similarly, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) envisions “A healthier future through learning, discovery, health care and community collaborations, as it leads and serves academic medicine to improve the health of people everywhere”. The accrediting organizations for these health professions ensure that academic programs uphold these missions and values.

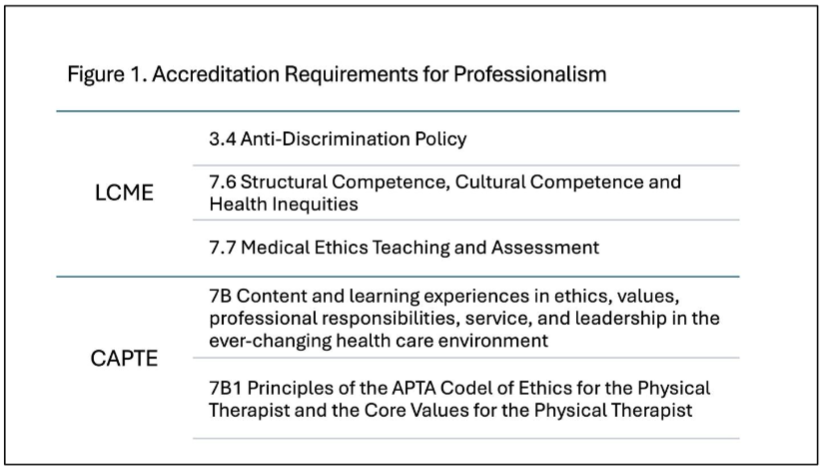

Accrediting bodies ensure that future professionals are enrolled in a legitimate, university-based academic program that prepares them for practice within the profession. Accrediting organizations collaborate with professionals within the field to define the body of knowledge and skills preparation appropriate to the profession, including setting standards for professionalism education. The Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) is responsible for accrediting medical education programs that confer Medical Doctorates in the United States, while the Commission on Accreditation in Physical Therapy Education (CAPTE) oversees Doctor of Physical Therapy programs. Medical internship, residency, and fellowship programs are accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. The American Board of Physical Therapy Residency and Fellowship Education oversees physical therapist residency and fellowship education.

Beyond setting standards for basic and clinical science curricula, accreditation organizations ensure that academic programs educate students in aspects of professionalism, including medical ethics. Examples are shown in Figure 1.

Professional organizations

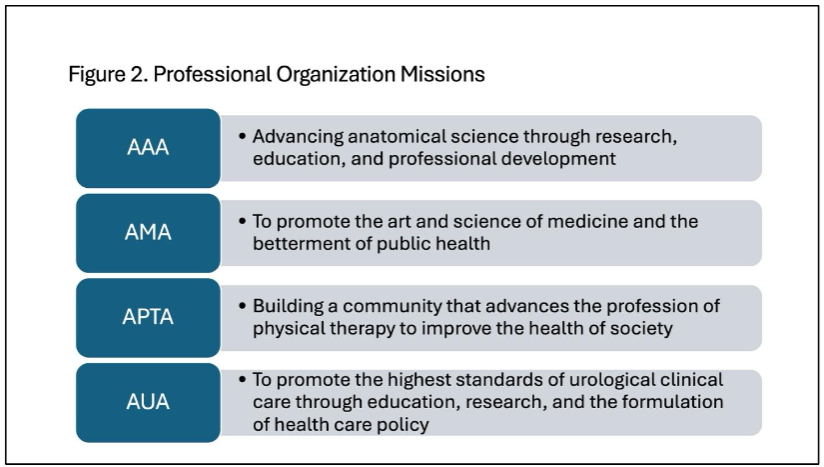

Each of our professions (anatomy, physical therapy, medicine, urology) has a professional organization with a clear mission and vision that guides the work of professionals within the occupation (Figure 2). Each of our professional organizations has also espoused core values and expectations of its member professionals. For example, the American Association for Anatomy values Community, Respect, Inclusion, Integrity, and Discovery. The American Medical Association values Leadership, Excellence, Integrity, and Ethical Behavior. The American Physical Therapy Association describes seven values that guide the behavior of its professionals: Accountability, Altruism, Compassion/Caring, Excellence, Integrity, Professional Duty, and Social Responsibility. The American Urological Association espouses the core values of Vision, Integrity, Respect, and Collaboration. It is worth noting that each professional organization values respect for the individual, a critical component of professionalism.

Education in professionalism

Awareness of professionalism begins before orientation and matriculation, and education about professionalism continues throughout one’s chosen academic program in health care. Entry into a program often requires an applicant to submit a personal statement along with their academic transcript and letters of recommendation. The personal statement is the first opportunity for a future health care professional to share (profess) why they aspire to be a health care provider, which typically includes sharing compassion and empathy for the less fortunate, a sense of fulfillment in helping others, a sense of justice (“helping others is right”), an affinity for scientific pursuit and discovery, and other professional traits we now take for granted as being associated with medicine. The statement provides admissions officers with insight into the applicant’s lived experience beyond their academic record or standardized test scores.

Once accepted into an academic program in health care, students may encounter their first patient, an individual who has given the selfless gift of body donation for anatomy education. Interactions with their deceased donor through dissection provide students with an opportunity to start practicing ethical, empathetic, and compassionate care. In today’s health care system, professionals often work in a team-based care environment. Holsinger and Beaton advocate for skill development in group work over purely autonomous practice, again drawing on the value of shared experiences in the anatomy laboratory. The values of respect, compassion, and integrity are evident in the donor memorial services held by nearly all anatomy education programs in the United States, services which are frequently organized by matriculating students.

Although professionalism is critical for high-quality health care, and disciplinary action by a state medical board after graduation is strongly associated with unprofessional behavior in medical school, there is no formalized curricular method to teach professionalism in health professions programs. A survey of the existing literature reveals a myriad of methods in use, including deceased donor dissection, role-play simulations, film discussions, video case presentations, written reflections, reading assignments, lectures, service-learning activities, and small group discussions. Role modeling and personal reflection are considered best practices in medical education. In each profession, role modeling and feedback on professional behaviors continue throughout experiential education in a clinical care environment. Faculty development is also essential, and Al-Eraky described 12 tips to empower faculty members to teach professionalism at all levels of medical education, from admissions through residency and into independent medical practice.

Regardless of the educational approach, professionalism demands that health care providers acknowledge and respect individual patient differences, first recognized in the anatomy lab. Health care professionals must also become adept at working with individuals from diverse cultures, as presented by both patients and colleagues. Providers of care see individuals as they present and treat the patient in front of them, in alignment with the ethical principles of autonomy and justice. They appreciate that numerous factors influence a patient’s health, including age, ethnic identity, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, social network, intelligence, physical abilities, and life experiences.

Gender identity and health

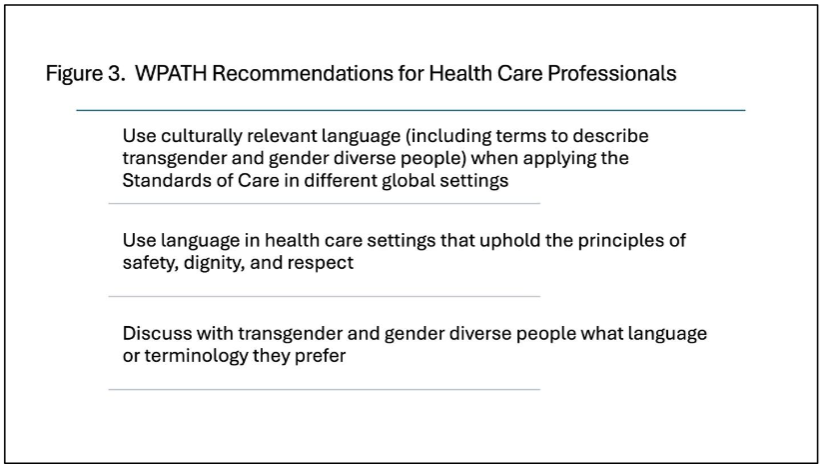

Just as age, intellect, or physical ability can affect a person’s health, gender identity or gender expression also influence one’s lifestyle choices and, in turn, one’s health and desired care. Becker and Ahmed make a case for continuing sex differences research, noting that gender is “not only composed of identity, but also roles and relations that can directly impact health outcomes”. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), the leading worldwide organization establishing evidence-based guidelines for gender-affirming care, explains that for all of mankind, gender is a spectrum, and hence diversity is natural. As shown in Figure 3, WPATH has published statements to guide health care practitioners in person-centered care of transgender and gender diverse people. The statements are purposefully broad, in recognition of the changing nature of language and the diversity of cultures and geographic regions. The WPATH Standards of Care-8 contains a glossary of terms presently in use. Despite the challenges of communicating across the world, the statements uphold the professionalism tenet, respect for persons.

Impact of executive orders on patient care

Recognition of gender identity and use of federal funds to promote gender ideology have been denied in the U.S. President’s recent Executive Order 14168, including housing and medical care for persons who are incarcerated (Defending Women From Gender Ideology Extremism and Restoring Biological Truth to the Federal Government). Denial of gender identity extends to the military, as Executive Order 14183 (Prioritizing Military Excellence and Readiness) states that, “expressing a false ‘gender identity’ divergent from an individual’s sex cannot satisfy the rigorous standards necessary for military service” and calls for an update of Medical Standards for Military Service. These Orders present a challenge in professionalism for health care providers working with persons who self-identify as non-binary or not fitting with their “biological sex”.

Executive Order 14187 (Protecting Children from Chemical and Surgical Mutilation) eliminates funding and federally sponsored research for gender affirming hormone therapies (including puberty-halting medications) and gender-affirming surgeries for people under age 19, and directs the Secretary of Health and Human Services to “end” such care throughout by a varied, but vague, list of measures. United States adults aged 18 are affected by the parameters of this Order. It should be noted that the title and text of this Order use the term “child” for the population the Order is intended to protect, yet “child” refers to a minor who has not yet commenced puberty. The WPATH has never advocated for providing medications or surgery to “children” in its nearly 100-year history.

An “adolescent” is a minor who has commenced puberty. The WPATH care guidelines dictate that only minors who have commenced puberty (i.e. adolescents) are eligible for hormone therapies or surgery. Note, the only surgery regularly offered to minors is chest reduction surgery for trans-masculine male youth, and only with a high bar of agreement amongst the patient’s medical and mental health providers. The WPATH currently sets no lower-limit age restrictions for medical or masculinizing chest reduction surgery because the onset of puberty is highly variable across both individuals and ethnic populations.

The aforementioned Executive Orders both eliminate and oppose gender-affirming health care and health care research for sizable populations of the U.S. public. According to U.S. Census-based studies, the proportion of the U.S. population that self-identifies as transgender is less than one percent (0.65%; approximately 1.65 million people). Today, among U.S. adults (age>18) 0.5% (1.5 million) self-identify as transgender, and among U.S. youth ages 13-17, 1.4% (300,000) self-identify as transgender. Obviously, amongst those who identify as gender diverse are healthcare practitioners and learners. The Executive Orders make it exceedingly difficult for gender diverse and sexuality-diverse people to live as their authentic selves.

The adverse effects of these Executive Orders on our healthcare system are yet to come. To use gender affirming care as an example, one must consider why the U.S. Government funded gender affirming care to begin with. The Department of Health and Human Services recognized that lack of access to gender affirming care contributed to high costs on the U.S. healthcare system, from medical disability costs, suicide, drug use, and other self-harming behaviors that have been shown to be associated with gender dysphoria. Work by Padula et al. showed that access to gender-affirming care increased the quality of life for this population, resulting in significantly lower costs for our healthcare system. A retreat from this approach, in alignment with the aforementioned Executive Orders, will almost certainly result in increased costs to our health care system related to decreased quality of life of youth and adults denied gender affirming care. Similarly, defunding health disparities research focusing on women, racial, cultural, sexuality, and other minorities will also decrease quality of life and increase unsustainable costs to our health care system.

The adverse effects of these orders on health care research will be felt for years to come. The halt in scientific research will adversely affect the healthcare of Americans, at a minimum in the short term, and in the future owing to the natural lag-time in scientific output. Databases used for training artificial intelligence algorithms will be lacking patient details necessary for development of clinical practice guidelines, an existing problem that will be compounded under new government policies. These Executive Orders do not align with either medical science or the core principles of medical ethics.

Impact of executive orders on autonomy of the profession

Dictates from outside the profession present an existential threat within higher education and medical practice. Restrictions on training and support programs addressing diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility impact health professions education, affecting current learners, faculty, and future health care providers. The recent Executive Order 14279 (Reforming Accreditation to Strengthen Higher Education) requiring accreditors to use data to improve outcomes, but specifically prohibiting reference to race, ethnicity, or sex, further erodes professional autonomy. Over-reach from outside the profession is at variance with the “occupationally controlled training program associated within a university”, one of the defining elements of a profession.

Limitations on patient choice exist in the health care system, but the Executive Orders referenced herein affect a person’s right to live authentically. Health care professionals have a moral obligation to respect the person in front of them, and they practice within a context of limitations of patient autonomous choice. Health care providers already work within health care structures that limit clinical practice and patient choices. Examples include financial coverage limitations, specialist referral requirements, and access to medical drugs, equipment, or procedures. Restrictions on recognition of gender identity, and restrictions on any research that focuses on disparities related to sex, gender and sexuality, and any recognition of ethnic/cultural diversity, all challenge our ability as healthcare providers to uphold the core ethical principles of our profession (beneficence, non-maleficence, autonomy, and justice). We seek to address this moral dissonance by educating ourselves and others and advocating for inclusive practices in health care.

Professionalism and health care education in today’s climate: how do we ensure a bright future?

Although we have focused this treatise on recent actions in the United States, we recognize that countries across the world have recently or historically seen similar challenges. We also understand that United States policies may have broad international impacts. Current events have brought increased awareness to the challenges faced by the trans community. This is an opportunity to dispel myths, to broadly disseminate evidence in practice, to improve health professional education at large, and to further demonstrate the value of personalized health care.

As professionals in health care and higher education, we must continue to pursue scientific work to advance care for minority groups. We must hold to the scientific method, which requires reviewing all existing information, avoiding confirmation bias in our analyses. We must welcome conflicting perspectives, debate and confirm studies, and base our clinical and educational approaches on scientific proof. We are all aware of history’s failures in politically influenced science, and we must do all we can to understand the impacts of politically driven science on society and science. We must continue the critically important work to improve the health of individuals and marginalized groups, though with less reliance on federal funding and within the constraints set by the Executive Orders. At the same time, we can exercise our democratic rights and advocate for eliminating the constraints, basing our arguments on scientific evidence.

As health care and education professionals, we must uphold our cherished ethical standards. Every one of us must find ways to reduce moral dissonance in our everyday practice by acknowledging the patient or learner in front of us, by learning from them, advocating for them, and by working to improve the system. We must continue to find joy and purpose in medicine and health professions education and model the facets of professionalism we have reviewed above to our students and trainees, to help cultivate their own sense of ethical standards, and most of all, compassion, and respect for all patients.

Conclusion

As professionals in health care and higher education, we are members of an occupation in which we “profess” to be skilled, and we have a professional, moral obligation to uphold the principles of medical ethics — beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy and justice. Recent Executive Orders in the United States denying gender identity, opposing gender affirming health care, and restricting funding and programs addressing diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility do not align with these ethical principles. Although we face moral distress, as professionals we must continue to provide patient-centered, scientifically sound care for all. While working within the law, we must follow the scientific method, conducting inclusive research that supports or refutes approaches to care for persons who identify as transgender or gender diverse. The current environment provides an opportunity for education, and we have outlined resources for learning and discussing this sensitive issue, focusing on the meaning and responsibilities of professionalism in health care.

Conflict of Interest:

None

Funding Statement:

None.

Acknowledgements:

None.

References:

- Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. Eighth edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2019. Print.

- Baker R. Anchor bias, autonomy, and 20th-century bioethicists’ blindness to racism. Bioethics. 2024; 38:275-81. doi: 10.1111/bio.13258. Epub 2024 Jan 2.

- Federal Register, Executive Order 14168, January 20, 2025. Defending Women From Gender Ideology Extremism and Restoring Biological Truth to the Federal Government. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/01/30/2025-02090/defending-women-from-gender-ideology-extremism-and-restoring-biological-truth-to-the-federal. Published January 30, 2025. Accessed April 15, 2025.

- Federal Register, Executive Order 14148, January 20, 2025. Initial Rescissions of Harmful Executive Orders and Actions. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/01/28/2025-01901/initial-rescissions-of-harmful-executive-orders-and-actions. Published January 28, 2025. Accessed April 15, 2025.

- Federal Register, Executive Order 14151, January 20, 2025. Ending Radical and Wasteful Government DEI Programs and Preferencing. Available from: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/01/29/2025-01953/ending-radical-and-wasteful-government-dei-programs-and-preferencing. Published January 29, 2025. Accessed April 15, 2025.

- Oxford English Dictionary. Available from: https://www.oed.com/?tl=true. Accessed April 27, 2025.

- Merriam-Webster. Available from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/. Accessed April 27, 2025.

- Friedson E. Theory of professionalism: method and substance. Intl Rev Sociol. 1999;9(1):117-129. doi: 10.1080/03906701.1999.9971301

- Federation of State Medical Boards. Available from: https://www.fsmb.org/ Accessed April 28, 2025.

- Federation of State Boards of Physical Therapy. Available from: https://www.fsbpt.org/ Accessed 28 Apr 2025.

- AMA Declaration of Professional Responsibility. Available from: https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/ama-declaration-professional-responsibility# Accessed April 15, 2025.

- Heston TF, Pahang JA. Moral injury and the four pillars of bioethics. F1000Res. 2023 Dec 28;8:1193. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.19754.4.

- American Council of Academic Physical Therapy. Available from: https://acapt.org/ Accessed April 15, 2025.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Available from: https://www.aamc.org/ Accessed April 15, 2025.

- LCME Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Standards, Publications, and Notification Forms. Available from: https://lcme.org/publications/ Accessed April 28, 2025.

- CAPTE Commission on Accreditation in Physical therapy Accreditation. 2024 PT Standards and Required Elements. Available from: https://www.capteonline.org/faculty-and-program-resources/resource_documents/accreditation-handbook Accessed April 28, 2025.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Available from: https://www.acgme.org/ Accessed April 28, 2025.

- American Board of Physical Therapy Residency and Fellowship Education. Available from: https://abptrfe.apta.org/ Accessed April 28, 2025.

- American Association for Anatomy. Available from: https://anatomy.org/ANATOMY Accessed April 15, 2025.

- American Medical Association. Available from: https://www.ama-assn.org/ Accessed April 15, 2025.

- American Physical Therapy Association. Available from: https://www.apta.org/ Accessed April 15, 2025.

- American Urological Association. Available from: https://www.auanet.org/ Accessed April 15, 2025.

- Escobar-Poni B, Poni ES. The role of gross anatomy in promoting professionalism: a neglected opportunity! Clin Anat. 2006;18(5):461-7. doi: 10.1002/ca.20353.

- Leeper BJ, Grachan JJ, Robinson R, Doll J, Stevens K. Honoring human body donors: five core themes to consider regarding ethical treatment and memorialization. Anat Sci Educ. 2024:17(3);483-498. doi: 10.1002/ase.2378.

- Youdas JW, Krause DA, Hellyer NJ, Rindflesch AB, Hollman JH. Use of individual feedback during human gross anatomy course for enhancing professional behaviors in Doctor of Physical Therapy students. Anat Sci Educ. 2013;6(5):324-31. doi: 10.1002/ase.1356.

- Holsinger JW Jr, Beaton B. Physician professionalism for a new century. Clin Anat. 2006;19(5):473-9. doi: 10.1002/ca.20274.

- Jones TW, Lachman N, Pawlina W. Honoring our donors: a survey of memorial ceremonies in United States anatomy programs. Anat Sci Educ. 2014;7(3):219-23. doi: 10.1002/ase.1413.

- Papadakis M, Teherani A, Banach MA, Knettler TR, Rattner SL, Stern DT, Veloski JJ, Hodgson CS. Disciplinary action by medical boards and prior behavior in medical school. N Engl J Med. 2005:353:2673-82. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa052596.

- Birden H, Glass N, Wilson I, Harrison M, Usherwood T, Nass D. Teaching professionalism in medical education: A best evidence medical education (BEME) systematic review. BEME Guide No. 25. Med Teach. 2013; 35(7):e1252-66). doi: 10.3109.0142159/x,2013.789132.

- Al-Eraky M. Twelve tips for teaching medical professionalism at all levels of medical education. Med Teach. 2015;37(11):1018-25. doi: 10.3109/1042159X.2015.1020288.

- Becker JB, Ahmed SB. Sex differences research is important! Biol Sex Differ. 2025;16(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s13293-025-00702-x.

- Coleman E, Radix AE, Bourman WP, et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. Intl J Transgender Health. 2022; 23(sup1):S1-S259. doi: 10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644.

- Federal Register, Executive Order 14183, January 27, 2025. Prioritizing Military Excellence and Readiness. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/02/03/2025-02178/prioritizing-military-excellence-and-readiness. Published February 3, 2025. Accessed April 15, 2025.

- Federal Register, Executive Order 14187, January 28, 2025. Protecting Children From Chemical and Surgical Mutilation. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/02/03/2025-02194/protecting-children-from-chemical-and-surgical-mutilation. Published February 3, 2025. Accessed April 15, 2025.

- Oles N, Fontenele R, Abi Zeid Daou M. Transgender history, Part II: a brief history of medical and surgical gender-affirming care. Behav Sci Law. 2025; Feb 24. doi: 10.1002/bsl.2719. Online ahead of print.

- Herman, J.L., Flores, A.R., and O’Neill, K.K., How Many Adults and Youth Identify As Transgender in the U.S.?, UCLA Williams Institute, 2022. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Trans-Pop-Update-Jun-2022.pdf Accessed: May 3, 2025.

- Karpel HC, Sampson A, Charifson M, Fein LA, Murphy D, Sutter M, Tamargo CL, Quinn GP, Schabath MB. Assessing medical students’ attitudes and knowledge regarding LGBTQ health needs across the United States. J Prim Care Community Health. 2023;14:1-13. doi: 10.1177/21501319231186729.

- Padula WV, Heru S, Campbell JD. Societal implications of health insurance coverage for medically necessary services in the U.S. transgender population: A cost-effectiveness analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2016; 31(4): 394-401. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3529-6. Epub 2015 Oct 19.

- Fong N, Langnas E, Law T, Reddy M, Lipnick M, Pirracchio R. Availability of information needed to evaluate algorithmic fairness – A systematic review of publicly accessible critical care databases. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2023;42(5):101248. doi: 10.1016/j.accpm.2023.101248.

- Federal Register, Executive Order 14279, April 23, 2025. Reforming Accreditation to Strengthen Higher Education. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/04/28/2025-07376/reforming-accreditation-to-strengthen-higher-education. Published April 28, 2025. Accessed May 6, 2025.

- Agledahl KM, Forde R, Wifstad A. Choice is not the issue. The misrepresentation of healthcare in bioethical discourse. J Med Ethics. 2011;37:212-5. Doi: 10.1136/jm3.2010.039172.

- Paul C, Brookes B. The rationalization of unethical research: Revisionist accounts of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study and the New Zealand “Unfortunate Experiment”. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(10:e12-e19. doi: 10:2105/AJPH.2015.302720.