Real-World Outcomes of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia in India

Beyond Guidelines: Real World Treatment & Outcomes of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia at a Tertiary Indian Cancer Centre

Linu Abraham Jacob1, Beulah Elizabeth Koshy1, Sindusha Kukunuri1, MC Suresh Babu1, Lokesh KN1,AHRudresha1, LK Rajeev1, Smitha C Saldanha1

- Department of Medical oncology Kidwai Memorial Institute of Oncology Dr. M. H. Marigowda road Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 May 2025

CITATION: JACOB, Linu Abraham et al. Beyond Guidelines: Real World Treatment & Outcomes of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia at a Tertiary Indian Cancer Centre. Medical Research Archives, [S.l.], v. 13, n. 5, may 2025. ISSN 2375-1924. Available at: <https://esmed.org/MRA/mra/article/view/6529>

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i5.6529

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

1. Introduction

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) is the most common type of leukemia diagnosed in the United States and accounts for about one-quarter of the newly diagnosed cases while it is one of the least common leukemias in India (< 5% of all leukemias) with incidence rates ten times lesser than in the US. The reason for the disparity in the disease frequency between the population of primarily European descent and that of the Orient, Asian and Mediterranean populations still continue to be a mystery. The fact that this trend persists in migrants to other countries, continuing into subsequent generations, shows that genetic predisposition is a likelier reason than environmental factors.

The characteristics of the disease including demographics, clinical presentation, treatment options, and outcomes also tend to vary between subcontinents and studies suggest that the course of the disease tends to be more aggressive in the South Asians with younger age of presentation, shorter time to first treatment and more frequent relapses with lesser time to next treatment.

The diagnosis of CLL requires sustained elevation of clonal B lymphocytes to >=5∗109/L for at least 3 months. Flowcytometry is used to demonstrate immunoglobulin light chain restriction and thus, clonality. The peripheral smear picture in CLL is described as small, mature lymphocytes with a rim of cytoplasm and a large nucleus lacking discernable nucleoli and partially aggregated chromatin. Smudge cells or gumprecht nuclear shadows are commonly associated with CLL. CLL cells co-express the surface antigen CD5 together with the B-cell antigens CD19, CD20, and CD23. The levels of surface immunoglobulin, CD20, and CD79b are characteristically low compared with those found on normal B cells. Each clone of leukemia cells is restricted to expression of either kappa or lambda immunoglobulin light chains. Chromosomal abnormalities in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) are detected in roughly 80% of patients. Among them, deletions of 11q, 13q, 17p, and trisomy 12 have a known prognostic value in CLL.

Certain genetic abnormalities have been found to be associated with adverse outcomes in response to standard chemoimmunotherapy regimens in some prospective trials. For example, patients that carry del 17p and/or TP53 mutations have been found to have better clinical outcomes when treated with nonchemotherapeutic agents, such as small molecule inhibitors of BTK, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, or BCL2.

CLL has been hypothesized to be a B cell receptor (BCR) signaling dependent malignancy. Mutated IGHV gene has been found to be associated with better prognosis as compared to patients with an unmutated IGHV gene (defined as 98% or more sequence homology to the nearest germline gene). Moreover, the presence of mutated IGHV gene is associated with excellent outcomes following chemoimmunotherapy with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab.

For CLL/SLL without del 17 p, BTKis with or without anti-CD20 mAb (continuous treatment) or Venetoclax + obinutuzumab (fixed duration treatment) or Chemoimmunotherapy (CIT) or immunotherapy (in special circumstances like IGHV-mutated CLL in patients aged < 65 years) are indicated in the first line setting.

In situations where BTKis and venetoclax are not available or contraindicated or rapid disease debulking needed, the options are:

- Bendamustine with anti-CD20 mAb

- Obinutuzumab with or without chlorambucil

- High-dose methylprednisolone (HDMP) with anti-CD20 mAb

For CLL cases with 17p deletion, CIT is not recommended since del 17p/TP53 mutation is associated with low response rates.

At our centre, the choice of treatment was at the discretion of the treating physician based on the performance status of the patient along with their financial and supportive care status. In general, fit patients who could afford the drug were offered the option of BTK inhibitors (especially if they were found to be TP53 mutated), while the fit, albeit financially unaffordable patients were offered BR regimen and the clinically unfit patients were offered chlorambucil with or without prednisolone based therapies.

With this study, we aim to describe the demographic, clinicopathological and treatment characteristics of CLL patients. While acknowledging the fact that our treatment strategy is different from the currently practised CLL guidelines due to financial limitations, we would like to describe the outcomes of the same in this paper.

2. Methods

This is a retrospective single centre study of newly diagnosed CLL patients conducted in the Department of Medical Oncology, Kidwai Memorial Institute of Oncology, Bengaluru from the year 2020 to 2023. The diagnosis, risk stratification, indication for treatment, response criteria, and adverse events were recorded as per International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia guidelines.

2.1 ELIGIBILITY

All consecutively diagnosed patients with CLL, above the age of 18 years, registered under the Department of Medical oncology were enrolled in the study.

2.2 BASELINE EVALUATION OF PATIENTS WITH CLL

Diagnostic tests:

- Tests to establish the diagnosis: CBC and differential count Immunophenotyping of peripheral blood lymphocytes

- Assessment before treatment: History and physical examination, performance status CBC and differential count Serum biochemistry, Direct antiglobulin test, Viral markers (HBsAg, HIV, Anti-HCV), Marrow aspirate and biopsy, CECT scan of neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis

- Additional tests before treatment: Molecular cytogenetics (FISH) for del 13q, del 11q, del 17p, trisomy 12, IGHV mutational status

Based on information from the above tests, patients were grouped as Rai Stage 0-IV.

Rai Staging

- Rai 0 – Lymphocytosis with Absolute leucocyte count > 5 ∗ 109/L

- Rai I – Lymphocytosis with lymphadenopathy

- Rai II – Hepatomegaly and/or splenomegaly with/without lymphadenopathy

- Rai III – Lymphocytosis and Hb < 11 g/dL with/without lymphadenopathy/ organomegaly

- Rai IV – Lymphocytosis and platelets < 100 ∗ 106/dL with/without lymphadenopathy/Organomegaly

2.3 INDICATION FOR TREATMENT

To initiate treatment in CLL, at least 1 of the following criteria needed to be met:

- Worsening marrow failure in the form of Hb < 10 g/dL and/or platelet counts < 100 ∗ 109/L

- Massive (i.e., >= 6cm below the left costal margin) or progressive or symptomatic splenomegaly.

- Bulky lymphnodes (i.e., >=10 cm in longest diameter) or progressive or symptomatic lymphadenopathy.

- Increasing lymphocytosis with an increase of >= 50% over 2 months, or with a lymphocyte doubling time (LDT) < 6 months; after excluding other causes of lymphocytosis.

- Autoimmune complications including anemia or thrombocytopenia poorly responsive to corticosteroids.

- Symptomatic or functional extranodal involvement (e.g., skin, kidney, lung, spine).

- Disease-related symptoms as defined by any of the following:

- Unintentional weight loss >= 10% within the previous 6 months.

- Significant fatigue (i.e., ECOG performance scale 2 or worse; cannot work or unable to perform usual activities).

- Fevers >= 100.5°F or 38.0°C for 2 or more weeks without evidence of infection.

- Night sweats for >= 1 month without evidence of infection.

2.4 SELECTION OF CHEMOTHERAPY REGIMENS

The choice of treatment was at the discretion of the treating physician based on the performance status of the patient along with their financial and supportive care status.

In general, fit patients with some financial support, were offered the option of BTK inhibitors (especially if they were found to be TP53 mutated), while the fit, albeit financially unaffordable patients were offered bendamustine-rituximab (BR) regimen and the clinically unfit patients were offered chlorambucil with or without prednisolone-based therapies.

Patients in the BTKi group received Ibrutinib at a dose of 420 mg/day. Patients in the BR group received Inj. Bendamustine 90 mg/m2 on D1 and D2 along with Inj. Rituximab 375 mg/m2 on D1 (for the first cycle) and 500 mg/m2 for subsequent cycles; q28 days. Patients in the Chlorambucil with Wysolone group received T. Chlorambucil 10 mg BD (D1-D7) with T. Prednisolone 40 mg OD (D1-D7) PO; q28 days. Toxicities were recorded and managed as per iwCLL guidelines.

2.5 RESPONSE ASSESSMENT

The response was assessed at 6 months after completion of the treatment as per iwCLL criteria. A complete History and Physical examination was done along with CBC and Serum Biochemistry. Computed tomography (CT) imaging was repeated. Bone marrow examination was not done in all patients. Hence, responses were documented as unconfirmed complete response (CRu).

2.6 TIME TO NEXT TREATMENT, RELAPSE-FREE SURVIVAL & OVERALL SURVIVAL

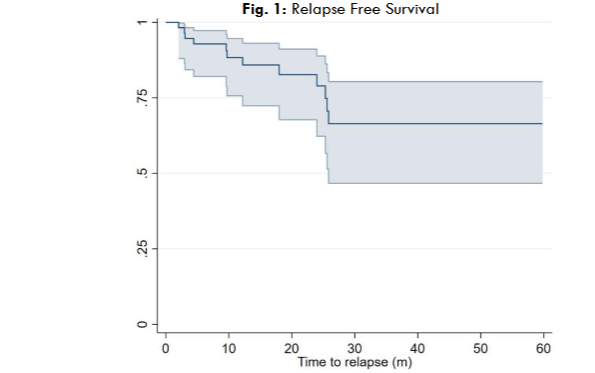

Relapse-free survival was defined as the interval between the last treatment day to the first sign of disease progression or death from any cause. Overall survival was defined as the interval between the first treatment day to death. Time to next treatment was defined in our study as the interval between the day of last treatment until the initiation of subsequent therapy for progressive CLL.

3. Statistical Methods

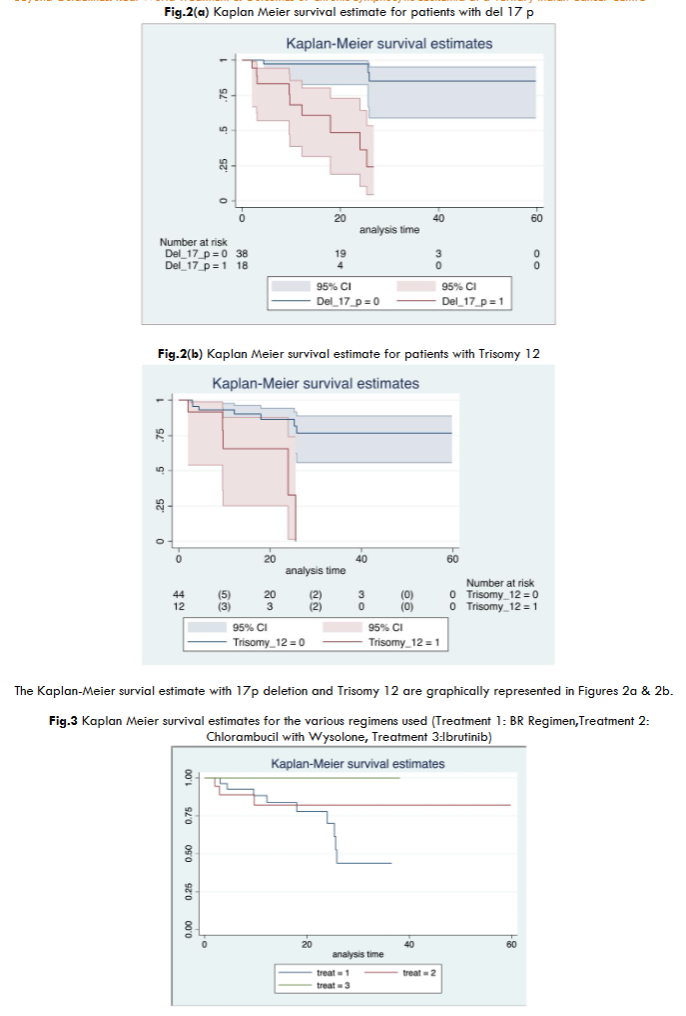

Categorical variables are reported as number and percentage and continuous variables as median and quartiles. Differences in proportions were assessed using the X2 or Fisher exact test. Cox Proportion Hazard model was used to compare relapse between various categories. Hazard ratio with 95% CI is reported. The time to relapse is presented using Kaplan-Meier analysis. A p value <= .05 was taken as statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed with STATA version 16.0.

4. Results

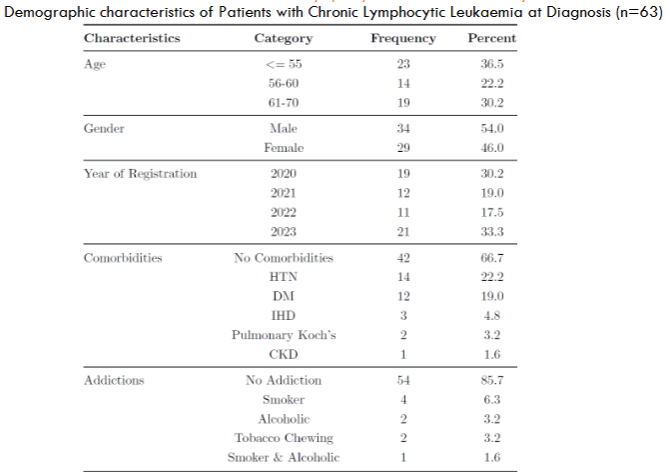

63 patients who were serially recruited from the year 2020 to 2023, with a median follow up period of 17 months (range: 6 to 36 months) and their demographic profiles are described:

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Median Age at Presentation | 60 years |

| Patients aged <= 55 years | 36.5% |

| Male Preponderance | Yes |

| Patients with No Comorbidities | Majority |

| Presenting Complaints | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Symptomatic Lymphadenopathy | Majority |

| Significant Fatigue | Followed |

| Symptomatic Organomegaly | Followed |

| Asymptomatic Patients | 11.1% |

| Median Values of Blood Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| TLC | 71,300 |

| S. Creatinine | Normal |

| Uric Acid Levels | Normal |

| Clinical or Laboratory TLS | No |

| Clinical Characteristics of Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia at Diagnosis | Value |

|---|---|

| B Symptoms at Presentation | 63.5% |

| ECOG PS | 2 and below |

| Family History of CLL | 2 patients |

| Generalised Lymphadenopathy | 71.6% |

| Hepatomegaly | 84.1% |

| Splenomegaly | 58.7% |

| DCT/ICT Positivity | 6 patients |

| Rai Stage IV | Majority |

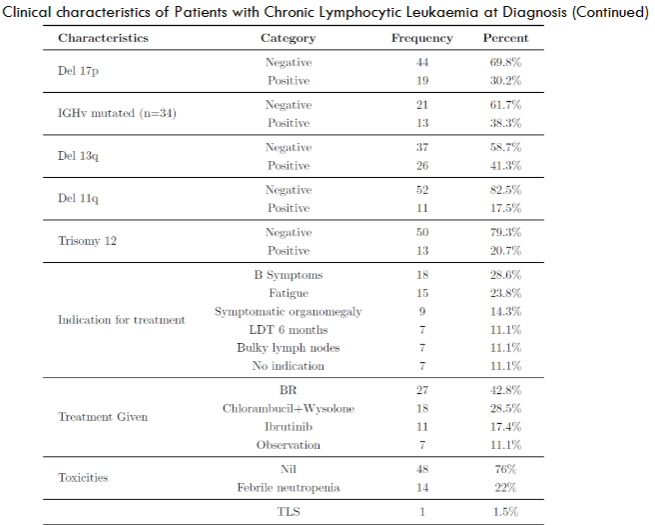

| Clinical Characteristics of Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia at Diagnosis (Continued) | Value |

|---|---|

| Chromosomal Abnormalities | 44 patients (69.8%) |

| Del 13q | 41.3% |

| Del 17p | 30.2% |

| Trisomy 12 | 20.7% |

| Del 11q | 17.5% |

| IGHv Mutation Status Checked | 34 cases |

| Positive IGHv Mutation | 38.3% (13 patients) |

| Reason to Initiate Treatment | B Symptoms (28.6%) |

| Fatigue | 23.8% |

| Symptomatic Organomegaly | 14.3% |

| Observation Cohort | 7 patients |

| Most Common Regimen | BR regimen (42.8%) |

| Chlorambucil with Wysolone | 28.5% |

| Ibrutinib | 17.4% |

| Toxicities After Treatment | Majority did not develop |

| Febrile Neutropenia | 22% |

| BR Regimen Causing FN | 78% |

| Chlorambucil with Wysolone | Less Frequent |

| TLS Reported | 1 patient |

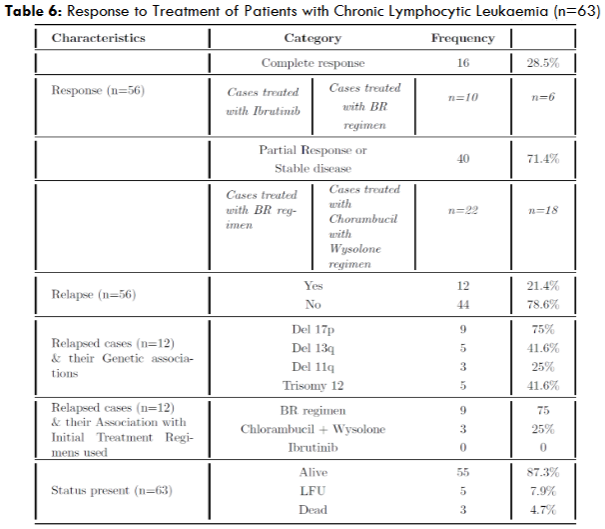

| Response to Treatment of Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia | Value |

|---|---|

| Treated Cases | 56 cases |

| Complete Response Achieved | 28.5% |

| Treated with Ibrutinib | All patients |

| PR or SD Achieved | 40 cases |

| Treated with BR Regimen | 21 cases |

| Treated with Chlorambucil + Wysolone | 18 cases |

| Relapsed Cases | 12 cases |

| Del 17p Associated with Relapse | 75% |

| Most Common Regimen Associated with Relapse | BR regimen (75%) |

| Chlorambucil with Wysolone | Followed |

| No Relapses Seen in Ibrutinib Cohort | Yes |

5. Discussion

CLL in the Western world is rare before the fourth decade of life with a median age of diagnosis of 72 years. The upper age limit for definition of patients with CLL as “younger” has varied between 50 and 55 years in published reports and accounts for only about 10-20% of newly diagnosed patients. In contrast to the Western data, majority of our patients presented in the younger cohort, with patients aged <= 55 years comprising 36.5% of the total patient population, with a median age of 60 years (about a decade lesser than our Western counterparts).

These findings closely correlate with other published Asian and Indian data on CLL. Risk of developing CLL is about two-times higher for men than for women as per Western data but among our patients, the disease seems to be almost equally distributed between men and women, with only a slight predilection for men.

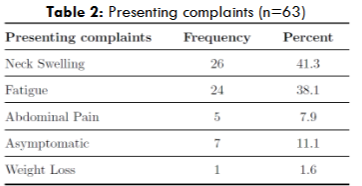

According to Western data, majority of patients at presentation do not require treatment and are asymptomatic. However, majority of our patients presented with a clinical history of symptomatic lymphadenopathy followed by significant fatigue, with asymptomatic patients constituting only 11.1% of the study group.

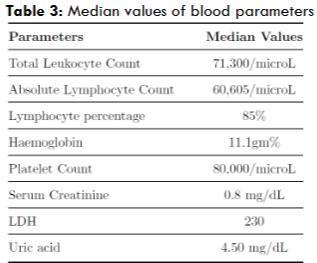

Even though our patients presented with greater disease burden (in the form of higher stages of Rai at presentation) with most of them requiring upfront treatment, their hematological and biochemical parameters, however, were grossly normal, with median TLC value of 71,300. This must probably be the reason why none of our patients presented with spontaneous TLS. However, the median platelet count was found to be 80,000/microL, owing to the fact that majority of our patients presented in Rai Stage IV.

Only a minority of patients had DCT/ICT positivity (6 patients) and this hence explains the median LDH being in the normal range. For such patients, we initiated a short course of oral steroids (wysolone) at 1mg/kg/total body weight and confirmed marrow involvement with bone marrow aspiration and biopsy before grouping them as Stage III/IV disease.

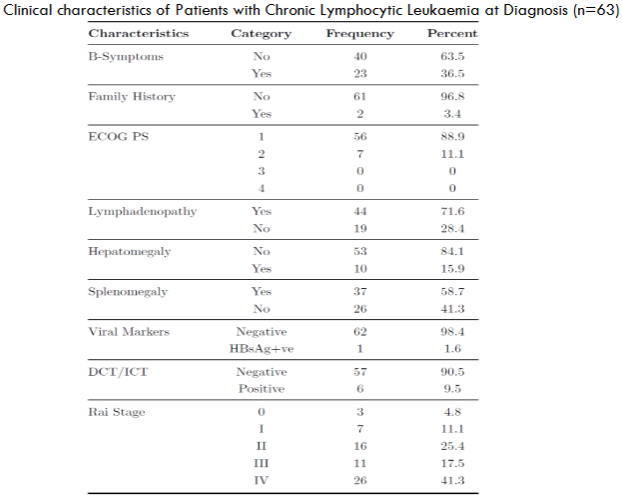

All the patients studied had an ECOG PS of 2 and below, probably owing to the younger age at presentation and lack of comorbidities. Majority of our patients presented as Rai stages III and IV, signalling high morbidity and also probably accounting for early relapses and lesser TTNT.

Del 13q was the most common genetic abnormality seen in our population as well (similar to the Western data available). However, the incidence of deletion 17p (considered as a poor risk marker) and Trisomy 12 (considered as an intermediate risk marker) were higher in our population – probably accounting for the aggressiveness of the disease at presentation.

According to Western data, deletion of 17p is found in approximately 3–8% of CLL patients at diagnosis and can account for up to 30% in patients treated with chemotherapy. However, in our population, it was positive in 30.2% cases upfront. Del 11q was the least common genetic abnormality seen.

BR regimen was the most common regimen used (42.8%) followed by Chlorambucil with Wysolone and Ibrutinib. Among the patients who received BR regimen, febrile neutropenia and TLS were observed as toxicities. Chlorambucil with Wysolone regimen also resulted in febrile neutropenia, albeit in lesser frequency as compared to the BR regimen. This is accounted for by the fact that both regimens contain alkylating agents. The patients treated with Ibrutinib had no incidence of febrile neutropenia or TLS, since both the side effects are traditionally considered as chemotherapy–induced and is not known to be caused by Ibrutinib. There were no Ibrutinib –specific side effects observed in our patients.

All the patients treated with Ibrutinib achieved a CR at the end of 6 months, with no documented relapses, thereby reiterating the fact that BTKis are indeed, superior to CIT or Chemotherapy.

Among the relapsed cases, del 17p was found to be the most common genetic abnormality followed by del 13q and Trisomy 12. BR regimen was the most common regimen found to have been used among the relapsed cases. This is probably because most of the patients who received BR regimen had del 17p as well (7 out of 9 patients; 77%). These are the patients who should have ideally received BKTis or other nonchemotherapeutic agents as del 17p is found to be relatively resistant to chemotherapy. None of the patients who received BTKis relapsed, thus driving home the fact that they yield long lasting remissions, when compared to chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy.

In this study, the Median Overall survival was not reached.

6. Conclusion

CLL seems to be more aggressive in our population with younger age of presentation, higher disease burden (in the form of higher Rai stage), shorter time to first treatment (Majority of our patients presented upfront with indications for treatment initiation), higher incidence of del 17p upfront and more frequent relapses with lesser time to next treatment. Del 17p remains a risk factor in our population with statistically significant lesser RFS in patients. Bruton Tyrosine Kinase inhibitors (BTKis) seem to be the best regimen for CLL patients in that it had no documented adverse effects, and yielded complete responses and long lasting remissions. Chlorambucil + wysolone remains a good option in resource limited settings and had lesser relapse rates than the cohort treated with BR regimen, with lesser adverse effects. The regimen however did not result in complete response in any of the patients.

Declarations

6.1 ETHICAL APPROVAL

Ethical Committee clearance was not required for this study as per institutional protocol since it is a retrospective study.

6.2 FUNDING

This study was not funded by any organization or body.

6.3 COMPETING INTERESTS

There are no financial or non-financial competing interests in this study. The authors of this study, are only affiliated to the institution where the study was held.

6.4 DATA AVAILABILITY

Not Applicable.

Keywords

chronic lymphocytic leukemia, tertiary indian cancer centre, treatment outcomes, relapse-free survival, bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors, demographic characteristics

References

2. Yang, S.-M., Li, J.-Y., Gale, R. P. & Huang, X.-J. The mystery of chronic lymphocyticleukemia (cll): Why is it absent in asians and what does this tell us about etiology, pathogenesis and biology? Blood reviews 29, 205–213 (2015).

3. Gunawardana, C. et al. South asian chronic lymphocytic leukaemia patients have more rapid disease progression in comparison to white patients. British journal of haematology 142, 606–609 (2008).

4. Belinda Austen, Chaminda Gunawardana, Guy Pratt, Farooq Wandroo, Abe Jacobs, Judith Powell, Paul Moss; Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia Has a More Aggressive Phenotype in Asians Compared to Caucasians. Blood 2006; 108 (11): 4965. doi: https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.V108.11.4965.4965

5. Hallek, M. et al. iwcll guidelines for diagnosis, indications for treatment, response assessment, and supportive management of cll. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 131, 2745–2760 (2018).

6. Puiggros, A., Blanco, G. & Espinet, B. Genetic abnormalities in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: where we are and where we go. BioMed research international 2014, 435983 (2014).

7. Stefaniuk, P., Onyszczuk, J., Szymczyk, A. & Podhorecka, M. Therapeutic options for patients with tp53 deficient chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Narrative review. Cancer management and research 1459–1476 (2021).

8. Shanafelt, T. D. et al. Ibrutinib–rituximab or chemoimmunotherapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine 381, 432–443 (2019).

9. Stephens, D. M. Nccn guidelines update: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 21, 563–566 (2023).

10. Hallek, M. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: 2020 update on diagnosis, risk stratification and treatment. American journal of hematology 94, 1266–1287 (2019).

11. Parikh, S. A. et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia in young (<=55 years) patients:a comprehensive analysis of prognostic factors and outcomes. haematologica 99,140 (2014).

12. Francesca R. Mauro, Robert Foa, Diana Giannarelli, Iole Cordone, Sabrina Crescenzi, Edoardo Pescarmona, Roberta Sala, Raffaella Cerretti, Franco Mandelli; Clinical Characteristics and Outcome of Young Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Patients: A Single Institution Study of 204 Cases. Blood 1999; 94 (2): 448–454. doi: https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.V94.2.448

13. Ferrajoli, A. Treatment of younger patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia.Hematology 2010, the American Society of Hematology Education Program Book2010, 82–89 (2010).

14. Tejaswi, V and Lad, Deepesh P and Jindal, Nishant and Prakash, Gaurav and Malhotra, Pankaj and Khadwal, Alka and Jain, Arihant and Sreedharanunni, Sreejesh and Sachdeva, Manupdesh Singh and Naseem, Shano and others. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: real-world data from india. JCO Global Oncology 6, 866–872 (2020).

15. Agrawal, N. et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia in india-a clinico-hematological profile. Hematology 12, 229–233 (2007).

16. Rani, L. et al. Comparative assessment of prognostic models in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: evaluation in indian cohort. Annals of Hematology 98, 437–443(2019).

17. Choi, Y. et al. Treatment outcome and prognostic factors of korean patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a multicenter retrospective study. The Korean Journal of Internal Medicine 36, 194 (2021).

18. Wainman, L. M., Khan, W. A. & Kaur, P. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Current knowledge and future advances in cytogenomic testing. Exon Publications 93–106(2023).

19. Molica, S. Sex differences in incidence and outcome of chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients. Leukemia & lymphoma 47, 1477–1480 (2006).

20. Molica, S. et al. The chronic lymphocytic leukemia international prognostic index predicts time to first treatment in early cll: Independent validation in a prospective cohort of early stage patients. American journal of hematology 91, 1090–1095(2016).

21. Delgado, J. et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with 17p deletion: a retrospective analysis of prognostic factors and therapy results. British journal of haematology 157, 67–74 (2012).

22. Konstantinov, S. & Berger, M. Alkylating agents. Encyclopedia of Molecular Pharmacology; Offermanns, S., Rosenthal, W., Eds 53–57 (2008).

23. Lipsky, A. & Lamanna, N. Managing toxicities of bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Hematology 2014, the American Society of Hematology Education Program Book 2020, 336–345 (2020).

24. Zenz, T. et al. Risk categories and refractory cll in the era of chemoimmunotherapy.Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 119, 4101–4107(2012).