Remote Storytelling: Enhancing Adolescent Mental Health

Wellbeing Through Remote Storytelling: A Digital Arts Intervention for Indian Adolescents During Pandemic Isolation

Shravani Sandepudi1, Garima Sharma1, Noyonika Gupta1,Lavanya N. K1, Poulomi Sen1OPEN ACCESS

- NalandaWay Foundation, Chennai

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 May 2025

CITATION: Sandepudi, S., Sharma, G., et al., 2025. Wellbeing Through Remote Storytelling: A Digital Arts Intervention for Indian Adolescents During Pandemic Isolation. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(5). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i5.6339

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i5.6339

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic represents one of the most significant global health crises of modern times, with wide-ranging impacts on mental health, particularly for adolescents. This study was conducted to find the answer to the question: What is the impact of a remote storytelling intervention delivered through Interactive Voice Response System on the mental well-being of 10th-grade students experiencing stress due to school closures during the pandemic? The intervention aimed to address the psychosocial distress among adolescents in Tamil Nadu caused by school closures and pandemic-related isolation, using an innovative, remote storytelling approach. Over 30 days, the intervention leveraged narrative techniques and guided activities to support mental wellbeing for a sample of 9,728 class 10 students from government and aided schools.

Methods: A quasi-experimental, one-group pretest-posttest design was used, with mental wellbeing evaluated through the Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale and in-depth personal interviews.

Results: The intervention resulted in a significant improvement in the mental wellbeing of participants [t (9728) = 4.49, p < 0.01], particularly in areas such as relaxation, social connectedness, and decision-making ability.

Conclusion: The findings highlight the potential of remote storytelling interventions to address mental health challenges during public health crises, offering a scalable and accessible solution for promoting adolescent wellbeing.

Keywords: Adolescents, Interactive Voice Response System, Mental Wellbeing, Pandemic, Storytelling, COVID-19

Introduction

Adolescence is marked by significant biological, cognitive, and psychosocial changes. It represents both tremendous growth and increased vulnerability to psychological distress. This developmental period is characterized by a desire for independence, new experiences, and identity formation that shapes personality.

Adolescent Mental Health & COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic caused widespread disruption, isolation, and fear, significantly affecting mental health worldwide. Adolescents have been especially vulnerable due to their developmental stage, which involves emotional and social changes and limited coping mechanisms. Lockdowns, school closures, and social isolation intensified psychological stress, leading to increased anxiety, depression, and related concerns. Globally, 10–20% of adolescents already experience mental health disorders, a statistic likely worsened by pandemic-related stress. Adolescents, frequently exposed to high stress, became more prone to issues such as depression, anxiety, and anger during this period.

Research highlights strong links between the pandemic and elevated levels of anxiety, depression, and substance use, including alcohol and cannabis.

Impact on Adolescents in Tamil Nadu & Storytelling-Based Interventions

The COVID-19 lockdown in Tamil Nadu severely impacted adolescents by cutting off physical interaction with peers, leading to frustration, disrupted routines, and reduced emotional wellbeing. School closures further destabilized mental health, especially among those with pre-existing conditions, as the loss of structure and last-minute exam changes heightened anxiety and stress. A survey revealed over 20% of students reported extreme stress before exam postponements, along with sleep and appetite issues.

Tamil Nadu, among India’s hardest-hit states, saw alarming stress levels during the early pandemic phase. One study found that in those under 25, 42.9% experienced mild-to-moderate stress, and 44.4% experienced severe stress—particularly among lower-income groups. Urban adolescents reported feeling confined and unhappy, while rural adolescents were less impacted due to more relaxed enforcement of distancing. Academic uncertainty was a common stressor, and tragically, at least one suicide was linked to online learning struggles.

Disruptions in daily routine also impacted adolescent sleep patterns. Prolonged screen time raised concerns about compulsive internet use, exposure to harmful content, and increased risk of abuse, especially given that school and legal support services were largely inaccessible during lockdown.

In response to these challenges, the current study explores a low-cost, accessible storytelling-based intervention via Interactive Voice Response System (IVRS) to support adolescent mental health. Storytelling is a dynamic, interactive form of human expression that can promote imagination, emotional processing, and self-reflection. Research suggests storytelling interventions can increase self-efficacy and reduce depressive symptoms among adolescents.

Key mechanisms of storytelling include emotional identification, immersion in narratives (transportation), and social rehearsal—processes that help adolescents model and apply positive behaviors. While such interventions have been studied internationally, there remains a gap in research specific to Indian adolescents. This study aims to fill that gap, contributing to the growing evidence base for digital, remote strategies that promote adolescent wellbeing during large-scale public health crises like COVID-19.

Method

Aim

The aim of this study is to address the psychosocial distress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and consequent school closures experienced by adolescents in the 10th grade across government and aided schools in Tamil Nadu, India. The intervention uses an IVRS to deliver a multimodal program designed to improve mental wellbeing through storytelling and activity-based engagement.

Research question

The study seeks to answer the following research question: What is the impact of an IVRS-based multimodal intervention on the mental well-being of 10th-grade students experiencing stress due to school closures during the pandemic?

Research design

This study employed a quasi-experimental, one-group pretest-posttest research design. The dependent variable was the participants’ level of well-being, while the independent variable was the exposure to a one-month digital multimodal intervention consisting of daily storytelling and activities delivered via IVRS.

Sample

The target population consisted of 620,000 students in the 10th grade across government schools in Tamil Nadu. A sample of 9,728 participants (Mean age = 15 years) was selected using stratified random sampling. The sample size for this study was determined using stratified random sampling to ensure representativeness across key demographic variables. The participants were selected based on population estimates of adolescent demographics in the region. The sample size was calculated considering a 95% confidence level and a margin of error. The population was stratified by the geographical distribution of districts, and participants were randomly selected from each district in proportion to the district’s population size. This sampling approach ensured the final sample was representative of the overall population distribution across the different geographic regions.

Tools

Short Warwick Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (SWEMWBS). A shortened version of Warwick Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale the SWEMWBS is a seven-item scale designed to evaluate the progress of interventions in the field of positive and promotive mental health amongst non-clinical populations. SWEMWBS has high internal consistency and has been validated to be used for a population with the ages of 15-21 years.

In-depth personal interview. A sample of (n = 50) children were selected using random sampling for conducting interviews. This was aimed at procuring deeper insight into the participant’s experiences, learnings and feedback of the programme.

Study procedure

After an extensive review of literature and needs assessment conducted with teachers, school counsellors and adolescents studying in class 10th, the objectives of the study were framed. The themes that emerged from the needs assessment were then mapped to the UNICEF Life Skills and Citizenship Framework. This was followed by development of the content, in terms of stories and activities, which were matched to four themes – 1. Understanding privacy and space, 2. Dealing with disruption in routine, 3. Dealing with anxiety and uncertainty, and 4. Making time for self and others.

This was followed by conduction of baseline survey with a selected sample to assess the participants’ initial well-being levels. To collect the data, IVRS was used. This was implemented from May to June 2020. Each day, a new story was uploaded and could be accessed by students via a toll-free number. Students would give a missed call to this number, after which an automated callback would play the story. The stories were available throughout the day. Each story included recommended activities that the participants could undertake. After the month-long intervention, an endline survey was conducted to assess changes in the participants’ well-being. Data from the pretest and posttest surveys were analysed to determine the impact of the intervention, and the results were reported.

The data collected from both the baseline and endline surveys were analyzed using a mixed-methods approach. Quantitative data from the IVRS-based surveys were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics, including paired t-tests to assess significant differences in well-being scores before and after the intervention. Thematic analysis was used to analyze qualitative responses, allowing for a deeper understanding of participants’ experiences and engagement with the intervention. The combination of these methods provided a comprehensive assessment of the impact of the storytelling intervention on adolescent well-being.

Results

| Item | N | Mean | S.D | t value | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Score Comparison | Baseline | 9728 | 18.61 | 5.05 | 4.49 | 0.00* |

| Endline | 9728 | 18.95 | 5.46 | *p value< 0.01 |

As per the data in Table 1, it is seen that there was a statistically significant improvement in the mental well-being scores of the selected sample post the intervention with mean scores increasing from 18.61 (baseline) to 18.95 (endline) [t (9728) = 4.49, p < 0.01]. This improvement confirms the effectiveness of the IVRS-based storytelling intervention at enhancing adolescent mental well-being during the pandemic, providing statistical validation for the approach.

| Items | N | Mean | S.D | t value | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. “I have been feeling optimistic about the future” | Baseline | 9728 | 3.14 | 1.04 | 2.12 | 0.03* |

| Endline | 9728 | 3.11 | 1.08 | |||

| 2. “I have been feeling useful” | Baseline | 9728 | 2.81 | 1.07 | 1.80 | 0.07 |

| Endline | 9728 | 2.78 | 1.09 | |||

| 3. “I have been feeling relaxed” | Baseline | 9728 | 2.31 | 1.03 | 7.47 | 0.00* |

| Endline | 9728 | 2.43 | 1.06 | |||

| 4. “I have been dealing with problems well” | Baseline | 9728 | 2.55 | 1.09 | 3.13 | 0.02* |

| Endline | 9728 | 2.60 | 1.11 | |||

| 5. “I have been thinking clearly” | Baseline | 9728 | 2.74 | 1.10 | 1.63 | 0.10 |

| Endline | 9728 | 2.77 | 1.12 | |||

| 6. “I have been feeling close to other people” | Baseline | 9728 | 2.52 | 1.15 | 4.84 | 0.00* |

| Endline | 9728 | 2.6 | 1.16 | |||

| 7. “I’ve been able to make up my own mind about things” | Baseline | 9728 | 2.53 | 1.08 | 8.27 | 0.00* |

| Endline | 9728 | 2.66 | 1.11 |

Data in Table 2 indicates that there was a statistically significant improvement in the feelings of relaxation, perceived problem-solving abilities, social connectedness, as well as decision making in the selected sample of adolescents post the intervention.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to address the psychosocial distress caused by the pandemic, specifically the stress associated with lockdowns and board exam uncertainties, faced by 10th-grade adolescents in government and aided schools in Tamil Nadu, India. This was achieved through an Interactive Voice Response System (IVRS)-based multimodal intervention. Data on the intervention’s impact on mental well-being was collected through the Short Warwick Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (SWEMWBS) and in-depth personal interviews. The findings and their implications are discussed below:

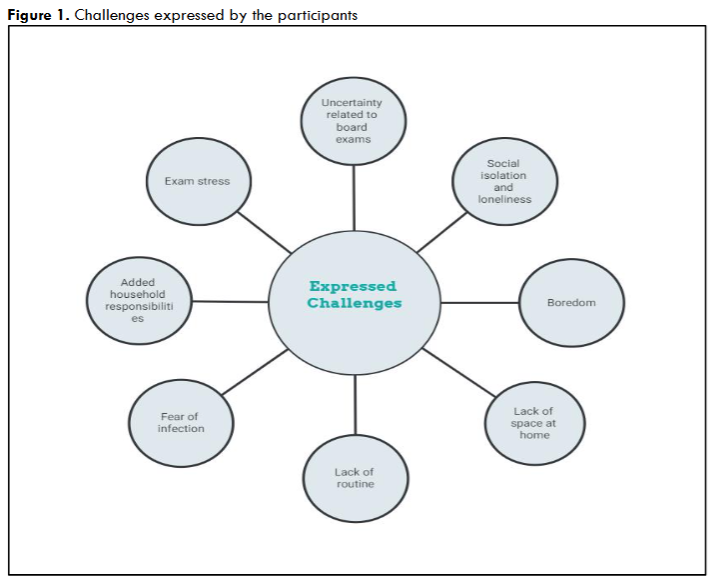

Expressed challenges

The participants highlighted several challenges they faced during the pandemic, as presented in Figure 1. A significant concern was the uncertainty surrounding the schedule of the board examinations. In India, these exams are pivotal as they certify the completion of middle school. Participants expressed stress and anxiety about the exams, compounded by the fear of contracting COVID-19 and how it might affect their exam performance. Additionally, participants reported feelings of social isolation due to school closures and the difficulty in maintaining friendships after many families relocated. The loss of daily routine following the lockdown contributed to boredom, while some participants faced challenges at home, such as lack of personal space and additional household responsibilities.

The adolescents in our study articulated several key challenges they faced during the pandemic period. Predominant among these was academic anxiety, particularly regarding the uncertain scheduling of board examinations and how COVID-19 might affect their performance. As one 16-year-old female participant stated, “I kept preparing for exams that might happen any day or might not happen at all. This uncertainty was more stressful than the actual studying.” Social isolation emerged as another significant concern, with many participants reporting feelings of disconnection from peers and difficulties maintaining friendships. The disruption of daily routines following school closures contributed to widespread reports of boredom and listlessness. Home environment challenges were also noteworthy, with participants describing limited personal space and increased household responsibilities. These combined stressors manifested in various ways, including sleep disturbances, difficulty concentrating, and heightened anxiety, illustrating the multifaceted impact of the pandemic on adolescent well-being.

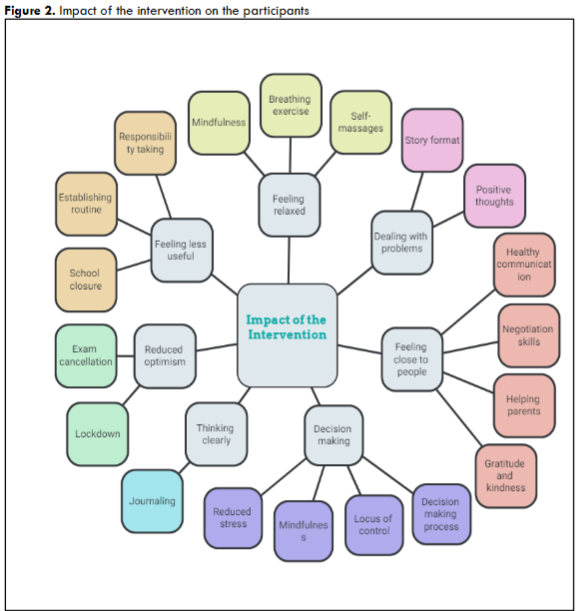

Impact of the intervention

The intervention presented significant impact in multiple areas for the adolescents as presented in Figure 2. The adolescents reported increased feelings of usefulness, relaxation, better ability to deal with problems among other positive outcomes.

The results obtained reveal that there has been a significant increase [t (9728) = 4.49, p < 0.01]. in the overall mental wellbeing of the participants in the endline (M=18.95), as compared to the baseline (M=18.61), as presented in Table 1. This improvement could be attributed to multiple factors like the format of the stories, nature of activities and other contextual influences.

From Table 2, it is seen that Statements 3 (“I have been feeling relaxed”), 4 (“I have been dealing with problems well”), 6 (“I have been feeling close to other people”), and 7 (“I’ve been able to make up my own mind about things”) have statistically significant improvement between the baseline and endline scores. Further, an increase in mean scores was observed for Statement 5 (“I have been thinking clearly”), though the improvement was not statistically significant. The improvements in the aforementioned domains could be attributed to two factors, the format of the stories and the activities suggested in the stories.

For instance, the participants engaged with a number of activities that involved bodily techniques for relaxation like breathing exercise, mindfulness exercises and self-massages. Past research in this field has shown the effectiveness of using similar techniques to improve relaxation amongst adolescents. A study demonstrated that using slow breathing exercises with adolescents in Coimbatore, India for a period of 30 minutes every day, for 45 days’ led to a significant decrease in anxiety levels and improved levels of relaxation. Similarly, research evidence points to the direction that regular and consistent engagement in mindfulness-based activities contribute to reduced physiological and emotional manifestations of stress, academic stress and stress due to peer interactions amongst high school students in Delhi, India.

Research has also shown that regular mindfulness practice can lead to improvement in problem solving abilities. Insights from qualitative interviews with the participants further validate this finding. As mentioned by a 15 year old male participant from Perumbakkam: “I first called just to check it out. But I liked it a lot. Take it eazy is a good gooooood programme….When I listen to Take It Eazy, I feel relaxed. The stories are very engaging, like the stories involve us… because of that, our mind feels satisfied (relaxed)…” Another male participant, 15 year old from the same district mentioned “It was relaxing… it was also useful. After listening to the episodes, I was thinking when they will put another episode…” Yet another 15 year old, male participant from Puddhukottai shared: “I learnt a lot through the programme…. Mind relaxation… I also made notes… under each date, I wrote what was told in that episode…. (reads from his notebook)… they talked about a lot of things… about child abuse, about helping others in the house… locus of control… about self respect… they talked about a lot of things…. They also spoke about unity, not to fight with others… I remember this during fights… then I feel a little relaxed… like this they spoke about a lot of things.”

The story format was designed in a manner that the protagonists constantly modelled problem solving behaviours in their interactions. In their study, elaborated on how storytelling is a befitting methodology to teach problem solving to individuals, as it exposes people to real life problems, and perspectives of experts who view situations in various ways, which might be different from how layman view it in their daily lives. Thus, the format of the stories could be one of the factors contributing to increased confidence in problem solving amongst the participants.

Studies have also shown that negative thoughts or rumination can result in reduced perception of control and interfere with a person’s problem solving abilities. Introducing the activity to replace these negative thoughts with positive ones and focus on the things one can control, could have also resulted in the adolescents feeling more confident about their abilities to solve problems. Additionally, the intervention introduces the participants to a number of learning strategies like mnemonics, colour coding texts, visual representations and using flashcards. The importance of having an academic routine and asking questions during the learning process was also emphasised in the process. These strategies have aided the learning process, and resulted in greater confidence with respect to learning. This is reflected in the following interview excerpts, highlighting the experience of a 15 year old girl from Perambulur.

“I really like the episodes. Right from the beginning, they asked to call and listen to the program, and so I listened to it, and right from the beginning it was really interesting, and it felt like my concerns were being addressed, like giving useful tips for exams, how to study and how to write etc…. I’ve called and listened to the program again and again, I really enjoyed it. I would have listened to each episode almost five times… During exams I feel really sleepy usually, but after listening to the program they gave a lot of tips on how to help with that, and that has been really useful for me.”

Since academic stress and uncertainty about the future happens to be one of the biggest stressors amongst adolescents in the given context, the assistance that the participants received in terms of alternative learning strategies probably contributed to them feeling more confident about their ability to deal with problems they encounter.

Social Isolation and Relationship-Building

Given that the participants are adolescents, feeling closer to their peer group compared to their parents is a common experience in this developmental stage. The participants also reported experiencing challenges like feelings of social isolation and confinement due to lack of interaction with friends. Keeping this in mind strategies to develop meaningful relationships with parents like practising healthy communication, negotiation and helping parents out in daily tasks were suggested. The following excerpt from 15 year old female participants, from Karur town, illustrates the same: “I had listened to all the programmes with my mother… I daily spend time to talk , play , fight (small) with my siblings”. Another 16 year old male participant from Salem city shared: “I am in contact with 5-6 of my friends…. I talk to them daily… Mostly….when will this lockdown be over… when will the school reopen… when can we meet…we discuss such things…. I told 2-3 of them about the programme. They said they are also listening to it.”

Strategies to deal with social isolation experienced by the adolescents due to the pandemic were also suggested. These involved activities such as engaging in acts of kindness, practising communication skills, helping parents at work and expression of gratitude. This is in line with research findings that suggest that communication practices are crucial for familial cohesion, overcoming experiences of separateness and adaptation particularly during. Further, engaging in acts of kindness has been proven to enhance wellbeing and social connectedness amongst adolescents. Thus, the kindness activities of the intervention could have potentially contributed to enhanced social connectedness amongst participants.

Journaling

Journaling was another activity that was introduced as a regular practice through the intervention. Research shows that regular practice of journaling helps in bringing greater clarity to thoughts and feelings. As journaling is a new concept, while some took to it quickly, some of the adolescents needed more clarity on it, as conveyed through the interview excerpt with a 15 year old boy from Peramblur: “I need little more time… it ends very fast, it feels like it is going and gets over before that… extending it a bit and adding more characters… making it more super… it is my feedback…. And… this journaling and meditation, how to do it is not clear… talk more about that… ”. Another excerpt from the in-depth interview with a 15 year old male participant from Perumbakkam depicts that some of the participants enjoyed journalling: “I also liked journal… like they told, I am writing journal daily, I am feeling good after it… helps me in thinking.”

Decision-Making and Control

It has been proven by research that stress, especially during uncertain times can impact the effectiveness of making decisions. The discussion on the process of decision making along with the improvements in the participants’ experiences of relaxation, clarity of thought and the perceived ability to deal with problems well has also contributed positively to improvement in their confidence to make decisions.

Decrease in Optimism

From Table 2, it is also seen that Statements 1 (“I have been feeling optimistic about the future”), has been a statistically significant decrease between the baseline and endline scores with a reduction in mean scores. This can be resulting due to the board exam cancellation and the lockdown. As many participants mentioned that they aimed at scoring more during the board examination and had scored less marks during half-yearly. Now that the exams are cancelled and weightage is being given to the half-yearly marks, the children are worried about their overall scores. Performance in board examinations is considered to be a significant stressor amongst adolescents in India, as reported by previous studies. This stressor was further exacerbated by the continued lockdown, uncertainties associated with exam schedule and lack of physical classes.

Feeling Useful

A decrease in mean scores was also observed for Statement 2 (“I have been feeling useful”). However, the difference was not statistically significant. Studies indicate that some of the major challenges faced by adolescents during the pandemic were related to an absence of structured school setting, which led to boredom and lack of innovative ideas for engaging in various academic and extracurricular activities. Some children have expressed lower levels of affect for not being able to play outdoors and not engaging in school activities. These findings are similar to the findings of the needs analysis conducted with the population of interest. To counter this, a number of activities were suggested in the intervention, such as techniques for tracking a routine, plotting a sleep graph, encouraging responsibility taking in terms of household chores and helping family members, and introduction to new activities like poetry and story writing. The qualitative insights obtained indicate that there has been a reported improvement amongst the participants in terms of following a routine. The following is an excerpt from an interview with a 15 year old girl from Karur, illustrating this point: “After the programme, mam, now I am sleeping by 9 pm and I get up early by 4.30 am and keep this a routine”. Similarly, a 16 year old male from Salem city shared: “I wake up early in the morning… after waking up I drink water… then I do yoga for some time… then.. I take a bath, eat… play with my friends… then I have my lunch in the afternoon… then I play for some time… then night…”

Further, excerpts from qualitative interviews also suggest that the participants reported enjoying new activities they have learnt through the stories they heard. As mentioned by one of the 15 year old female participants from Karur, “In the first episode, they talked about poetry writing and planting a tree… Recently I wrote a poem… like a mother talking to her son… (recites 2 lines). ” On similar lines, a 15 year old male from Puddhukottai shared: “I learnt a lot through the programme…. Mind relaxation… I also made notes… under each date, I wrote what was told in that episode…. (reads from his notebook)… they talked about a lot of things… about child abuse, about helping others in the house… locus of control… about self respect… they talked about a lot of things…. They also spoke about unity, not to fight with others… I remember this during fights… then I feel a little relaxed… like this they spoke about a lot of things.”

Both the introduction of a structured routine and new activities that the participants can engage in, are aimed towards reducing boredom and enhancing the feeling of productivity amongst the adolescents. However the uncertainties associated with the pandemic, the prolonged lockdowns, social distancing and lack of school structure have potentially contributed to a slight decrease in the mean of scores indicating the degree of usefulness the participants report feeling.

Limitations

Notwithstanding the positive results, the present study suffers from certain limitations. Firstly, there are a set of challenges associated with the medium used for conducting the intervention and study, i.e. IVRS technology and phone calls. This model did not allow scope for direct interactions with the participants. However, this medium was chosen with the goal of reaching out to maximum participants during the pandemic.

Secondly, the researchers had no control over the extraneous variables such as examination schedules, pandemic, socio-political or economic conditions, all of which had an impact on the participants’ reception of the intervention. Finally, the research study does not cover the ‘effect size’.

Future Directions: Implications for Policy and Practice

Recommendations for the future iterations include adding a visual component to the audio stories to enhance involvement and engagement of participants. Further, content can be made keeping in mind other stakeholders who impact the lives of the adolescents like teachers and parents. Overall, the study has far reaching consequences in the field of promotive and preventive mental health, and proves to be a model that can be explored further with different populations.

Conclusion

The present study was conducted to understand the impact of an IVRS based multimodal intervention, on the mental wellbeing of 10th standard students facing stress due to school closure amidst the pandemic. The findings of the study indicate that there was statistically significant improvement in the adolescents’ overall mental wellbeing with specific improvements in subjective feelings of relaxation and closeness with other people, as well as perceptions of one’s ability to deal well with problems and make up one’s mind about things. It was also observed that feelings of optimism and self usefulness had reduced due to various factors as discussed in paper.

The study highlights how insights from research can be integrated to design a comprehensive storytelling based promotive mental health intervention addressing concerns faced by adolescents during the pandemic.

Conflicts of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in relation to this study. The research was conducted independently, and there are no financial or personal relationships that could have inappropriately influenced the outcomes reported in this paper.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by UNICEF Tamil Nadu, which provided financial assistance for the design, implementation, and analysis of the intervention. The funding agency had no involvement in the study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of the findings.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to the school administrators, teachers, and staff who provided their valuable insights for designing the intervention. We also acknowledge the participants for their valuable time and insights, which made this research possible. Special thanks to the research team and volunteers who contributed to data collection, management, and analysis.

References

- Nebhinani N, Jain S. Adolescent mental health: Issues, challenges, and solutions. Ann Indian Psychiatry. 2019;3(1):4.

- Berk L. Child Development. Boston: Pearson Education; 2013.

- Pollard CA, Morran MP, Nestor-Kalinoski AL. The COVID-19 pandemic: a global health crisis. Physiol Genomics. 2020:549-557.

- Gavin B, Lyne J, McNicholas F. Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. Ir J Psychol Med. 2020;37(3):156-158.

- Bruining H, Bartels M, Polderman TJ, Popma A. COVID-19 and child and adolescent psychiatry: an unexpected blessing for part of our population? Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;30(7):1139-1140.

- Grant KE, Compas BE, Stuhlmacher AF, et al. Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: moving from markers to mechanisms of risk. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(3):447.

- Oosterhoff B, Palmer CA, Wilson J, Shook N. Adolescents’ motivations to engage in social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: associations with mental and social health. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(2):179-185.

- Duan L, Shao X, Wang Y, et al. An investigation of mental health status of children and adolescents in China during the outbreak of COVID-19. J Affect Disord. 2020;275:112-118.

- Tee ML, Tee CA, Anlacan JP, et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines. J Affect Disord. 2020:379-391.

- Chen F, Zheng D, Liu J, et al. Depression and anxiety among adolescents during COVID-19: A cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;86.

- Dumas TM, Ellis W, Litt DM. What does adolescent substance use look like during the COVID-19 pandemic? Examining changes in frequency, social contexts, and pandemic-related predictors. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(3):354-361.

- Kumar A, Nayar KR, Bhat LD. Debate: COVID‐19 and children in India. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2020;25(3):165-166.

- Lee J. Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(6):421.

- Smith L, Jacob L, Yakkundi A, et al. Correlates of symptoms of anxiety and depression and mental wellbeing associated with COVID-19: a cross-sectional study of UK-based respondents. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291.

- Lal P, Kumar A, Prasad A, et al. COVID-19 pandemic hazard–risk–vulnerability analysis: a framework for an effective Pan-India response. Geocarto Int. 2021:1-12.

- Ramasubramanian V, Mohandoss AA, Rajendhiran G, et al. Statewide survey of psychological distress among people of Tamil Nadu in the COVID-19 pandemic. Indian J Psychol Med. 2020;42(2):368-373.

- Anbarasu A, Bhuvaneswari M. COVID-19 pandemic and psychosocial problems in children and adolescents in Vellore-District. Eur J Mol Clin Med. 2020;7(7):334-339.

- Nath A. Tamil Nadu: Unable to handle stress of online lessons, class 11 student dies by suicide. India Today. March 11, 2021.

- Agoramoorthy GI. India’s outburst of online classes during COVID-19 impacts the mental health of students. Curr Psychol. 2021.

- Devarajan S, Mylsamy S, Venkatachalam T, Veerasamy G. Impact of lockdown on sleep wake cycle and psychological wellbeing in South Indian population: A Cross-Sectional and Descriptive Study. Int J Med Sci Nurs Res. 2021:12-16.

- UNICEF. Children at increased risk of harm online during global COVID-19 pandemic. Published April 15, 2020. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/children-increased-risk-harm-online-during-global-covid-19-pandemic

- Baldwin J, Dudding K. Storytelling in schools. Natl Storytelling Network. 2007:1-43.

- Esterling BA, L’Abate L, Murray EJ, Pennebaker JW. Empirical foundations for writing in prevention and psychotherapy: Mental and physical health outcomes. Clin Psychol Rev. 1999;19(1):79-96.

- Gortner EM, Rude SS, Pennebaker JW. Benefits of expressive writing in lowering rumination and depressive symptoms. Behav Ther. 2006;37(3):292-303.

- Pennebaker JW. Telling stories: The health benefits of narrative. Lit Med. 2000;19(1):3-18.

- Larkey LK, Hecht M. A model of effects of narrative as culture-centric health promotion. J Health Commun. 2010;15(2):114-135.

- Tennant R, Hiller L, Fishwick R, et al. The Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): development and UK validation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007:1-13.

- Ringdal R, Eilertsen MEB, Bjørnsen HN, Espnes GA, Moksnes UK. Validation of two versions of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale among Norwegian adolescents. Scand J Public Health. 2018;46(7):718-725.

- McKay MT, Andretta JR. Evidence for the psychometric validity, internal consistency and measurement invariance of Warwick Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale scores in Scottish and Irish adolescents. Psychiatry Res. 2017:382-386.

- UNICEF. Comprehensive Lifeskills Framework. UNICEF India; 2019.

- Sellakumar GK. Effect of slow-deep breathing exercise to reduce anxiety among adolescent school students in a selected higher secondary school in Coimbatore, India. J Psychol Educ Res. 2015;23(1):54-72.

- Anand U, Sharma MP. Effectiveness of a mindfulness-based stress reduction program on stress and well-being in adolescents in a school setting. Indian J Posit Psychol. 2014;5(1):17.

- Jonassen D, Serrano J. Case-based reasoning and instructional design: Using stories to support problem solving. Educ Technol Res Dev. 2002;50(2):65–77.

- Lyubomirsky S, Kasri F, Zehm K. Dysphoric rumination impairs concentration on academic tasks. Cognit Ther Res. 2003;27(3):309-330.

- Lyubomirsky S, Tkach C. The consequences of dysphoric rumination. UC Riverside. 2008.