Resilience in Critical Care: Lessons from COVID-19

Resilience Lessons from COVID-19: Strengthening Critical Care Infrastructure and Workforce Capacity

Nochiketa Mohanty

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6238-1342

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED 31 August 2025

CITATION Mohanty, N., 2025. Resilience Lessons from COVID-19: Strengthening Critical Care Infrastructure and Workforce Capacity. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(8). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i8.6760

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i8.6760

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The COVID-19 pandemic exposed critical vulnerabilities within global healthcare systems’ critical and emergency care infrastructure and workforce capacity. This paper, five years post-onset, evaluates the sustained focus on critical care preparedness and proposes actionable recommendations for future health crises, utilizing a resilience framework.

Lessons Learned from COVID-19: This review employs a 4R resilience framework (Robustness, Redundancy, Rapidity, and Resourcefulness) to analyze lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic regarding critical care infrastructure and workforce. It assesses the current state of preparedness in 2025, considering advancements like the WHO pandemic treaty and persistent challenges, and subsequently develops comprehensive recommendations.

Recommendations for Resilience: The pandemic revealed significant gaps in flexible infrastructure, supply chain resilience, and workforce capacity, leading to widespread burnout. While innovations like platform trials and the finalization of the WHO pandemic treaty have emerged, progress in critical care preparedness five years on remains mixed. Ongoing staffing shortages, rural ICU closures, and the re-emergence of infectious diseases underscore a partial loss of focus. Recommendations are categorized into infrastructure development (scalable facilities, critical care networks), workforce capacity (training, mental health support), research and innovation (sustained research, “sleeper” protocols), policy and funding, and addressing translation challenges (community capacity building, efficient transfer systems). Innovative solutions, including AI/ML, VR/AR, and crowdsourcing, are also proposed.

Conclusion: Building a truly resilient critical care system necessitates a proactive, sustained, and integrated approach. By strategically investing in scalable infrastructure, strengthening the workforce, fostering continuous research and innovation, and ensuring equitable access through community-level capacity and efficient transfer systems, healthcare systems can better withstand and adapt to future health emergencies.

Keywords

COVID-19, critical care, resilience, healthcare infrastructure, workforce capacity

Introduction

The emergence of COVID-19 in 2020 profoundly disrupted healthcare systems worldwide, with critical care services experiencing unprecedented strain. This manuscript, composed five years after the pandemic’s onset, assesses whether preparedness in this domain has been sustained and offers evidence-based recommendations to fortify resilience against future crises. The WHO pandemic treaty, finalized in 2025, marks a significant step toward equitable resource distribution and robust health systems—key pillars for critical care enhancement. Innovations such as the Hub and Spoke model demonstrate potential for optimizing service delivery, yet difficulties in translating community needs to specialized care persist. The recent re-emergence of COVID-19 variants and recent outbreaks, such as Mpox, further emphasize these vulnerabilities.

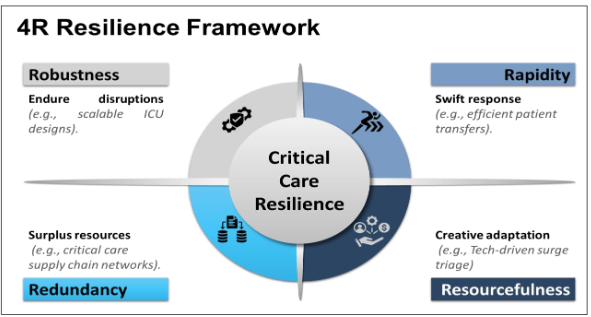

This analysis employs a resilience framework adapted from business continuity principles, structured around four dimensions (4Rs):

- Robustness: Capacity to endure disruptions while preserving function.

- Redundancy: Availability of surplus resources to ensure operational continuity.

- Rapidity: Swiftness in response and recovery.

- Resourcefulness: Ability to adapt creatively under pressure.

This figure illustrates the four dimensions of resilience Robustness (ability to withstand shocks), Redundancy (excess capacity or backups), Rapidity (quick response and recovery), and Resourcefulness (creative adaptation) and their application to critical care settings during health crises.

The subsequent sections explore lessons from the pandemic and propose strategies to strengthen critical care systems. The following is an effort to look at the lessons and way forward through the 4R lens.

Lessons Learned from COVID-19

The pandemic provided critical insights into the infrastructure and workforce needs of critical and emergency care, revealing both strengths and significant gaps.

Infrastructure Flexibility and Preparedness

The surge in critically ill patients overwhelmed healthcare systems, necessitating rapid adaptations:

- Flexible and Expandable Facilities: Hospitals repurposed operating theaters, general wards, and non-healthcare spaces into ad hoc intensive care units (ICUs). However, these makeshift solutions often lacked adequate utilities, equipment, or trained staff, potentially compromising care quality. For example, during peak surges, some hospitals converted conference rooms into ICUs, but inadequate ventilation systems posed infection control risks. This highlights the need for robust designs that can withstand surges.

- Critical Care Networks: Resource sharing and patient transfers were vital. The North West London Experience and French COORD-REA demonstrated effective patient distribution, acting as redundant systems to manage overflow by transferring patients to less pressured centers via road, rail, or air. Many regions lacked such networks, leading to delays and increased mortality.

- Supply Chain Vulnerabilities: Shortages of ventilators, oxygen, and personal protective equipment (PPE) were widespread. Incidents like the oxygen failure at Watford Hospital in the UK in 2020 and severe oxygen shortages in India in 2020 and 2021 COVID-19 outbreaks highlighted the need for robust supply chains and redundant stockpiles. Rapid innovations, such as mechanical CPAP devices, mitigated some shortages but were insufficient without coordinated logistics.

Workforce Struggles and Resilience

The pandemic placed unprecedented strain on the critical care workforce, testing robustness and resourcefulness:

- Staffing Shortages and Redeployment: Pre-existing shortages worsened due to illnesses, quarantines, and childcare issues. Nurse-to-patient ratios relaxed from 1:1 to 1:4 for ventilated patients. Redeployment of non-ICU staff, retirees, and students required rapid training, demonstrating resourcefulness. Just-in-time training was implemented to equip non-ICU staff to manage critically ill patients, but gaps in expertise persisted.

- Burnout and Mental Health: Intense workloads, ethical dilemmas (e.g., resource allocation decisions), and PPE shortages contributed to burnout, with 44% of ICU physicians reporting significant stress. Post-pandemic, many experienced nurses left the profession, exacerbating workforce shortages. This underscores the need for robust mental health support.

- Training Disruptions: Reduced elective caseloads and safety concerns limited hands-on training for critical care trainees, impacting the development of future professionals. This created a bottleneck in the supply of qualified intensivists and ICU nurses. Rapid training programs are essential to maintain workforce capacity.

Research and Innovation

The urgency of the pandemic accelerated critical care research. Genetic studies like GenoMICC deepened insights into disease susceptibility. Trials such as REMAP-CAP and RECOVERY rapidly pinpointed effective treatments, notably dexamethasone’s role in lowering mortality among severe cases. Yet, the focus on COVID-19 disrupted non-related research, leading to abandoned trials and wasted resources. This experience emphasizes the importance of maintaining diverse redundant research efforts during emergencies.

The WHO Pandemic Treaty and Critical Care

Ratified in April 2025, the WHO pandemic treaty seeks to bolster global health security through improved prevention, preparedness, and response. Its emphasis on equitable access to vaccines, treatments, and diagnostics is critical for critical care, where resource disparities were stark during COVID-19. The agreement includes provisions for securing and diversifying supply chains of essential medicines, PPE, and medical equipment, which are vital for critical care. It promotes stockpiling and distribution systems to prevent shortages during emergencies.

The treaty establishes a Pathogen Access and Benefit-sharing System to promote equitable sharing of innovations and a Coordinating Financial Mechanism to support sustainable financing. The treaty promotes international cooperation, which can lead to more effective sharing of critical resources such as ventilators, ICU beds, and medical supplies during crises. It encourages the development of surge capacity plans, ensuring healthcare systems are better prepared to handle sudden increases in critical cases. The treaty advocates for the harmonization of clinical guidelines, leading to more consistent and evidence-based care across regions, especially in emergencies. It supports the dissemination of best practices for managing severe cases, including treatment protocols for COVID-19 and other infectious diseases.

However, limitations, such as the 20% sharing requirement for pandemic-related products and weak accountability mechanisms, may hinder its effectiveness. While the pandemic treaty emphasizes international cooperation and data sharing, significant gaps in real-time surveillance, vaccine research, health system capacity, behavioral science, zoonotic origins, and legal frameworks still require focused research efforts. Filling these gaps is crucial for a more resilient global health landscape. From a critical care standpoint, strengthening these provisions could ensure that resources reach low- and middle-income countries, enhancing global capacity.

Current State Five Years Post-Pandemic

As of 2025, progress in critical care infrastructure and workforce capacity is mixed, with some advancements but persistent challenges.

- Infrastructure Developments: The PM-Ayushman Bharat Health Infrastructure Mission aims to establish critical care hospital blocks and integrated public health labs. However, in many countries like the United States, rural areas face ongoing challenges, with ICU capacity declining by 28.6% in counties with hospital closures compared to 7.3% in those without. Supply chain vulnerabilities persist, with various articles noting the need for sustained investment.

- Workforce Capacity: Staffing shortages and burnout remain significant. The 2023 update highlights high attrition rates among critical care professionals. Training disruptions continue to affect the pipeline of new intensivists and ICU nurses, compounded by broader workforce challenges, such as childcare issues impacting healthcare workers.

- Learning Networks in Critical Care: Learning networks have emerged as a powerful tool for resourcefulness and rapidity enhancing critical care. The CRIT CARE ASIA network, spanning 42 ICUs across nine Asian countries, uses a cloud-based registry for real-time data collection, enabling audit, feedback learning. This model allows clinicians to interact with data to identify problems and implement solutions, fostering continuous improvement. Such networks align with learning health systems, accelerating research and improving outcomes in resource-limited settings. The Hub and Spoke model regionalizes critical care, with tertiary hospitals (hubs) providing specialized care and community hospitals (spokes) offering initial stabilization, enhancing redundancy and rapidity. Experiences from SEAOHUN/AFROHUN wherein University Networks are supporting capacity enhancement of multisectoral teams on One Health implementation can be replicated for critical care. For example, telehospitalist programs in critical access hospitals use this model to provide virtual support from hubs to spokes, improving access to care. Tele-ICU models have shown to be associated with lower mortality, especially in medium and high-risk patients, and decreased EMR-related tasks of on-site physicians.

However, challenges include ensuring robust transfer systems and adequate training for spoke hospital staff.

Translating Community Needs to Tertiary Care

Critical care is inherently a tertiary-level service, requiring specialized equipment and staff not typically available at community hospitals. During COVID-19, community facilities struggled to stabilize critically ill patients, and transferring them to tertiary centers was logistically complex and risky. Key challenges include:

- Resource Disparities: Community hospitals often lack ventilators, ICU beds, and trained personnel.

- Transfer Logistics: Delays and risks in transferring critically ill patients can worsen outcomes.

- Training Gaps: Community staff need training to recognize and manage critical care patients initially.

- Equity Issues: Rural and underserved areas face barriers to accessing tertiary care, exacerbating disparities.

These challenges highlight the need for robust and redundant systems for community-level capacity enhancement to ensure equitable access.

Recent Challenges from Outbreaks

Five years post-pandemic, there appears to be a partial loss of focus on critical care preparedness. The suspension of non-COVID research and failure to restart some studies indicate a decline in research continuity. The drop in resources for research and public health due to the current geopolitical situation has led to the suspension of many critical initiatives across the globe. Public health funding has fluctuated. Government and non-government led initiatives like the PM ABHIM in India and Build Back Better Act in the United States provide initial momentum but have a long way to go to address long-term deficits. Rural ICU closures and ongoing staffing shortages further suggest waning momentum.

The re-emergence of COVID-19 variants continues to strain ICUs, requiring rapid reorganization even in 2024. Outbreaks like Mpox, in the African region, and diarrheal diseases in many Asian countries linked to poor sanitation, add pressure lead to disruption in non-emergency care, increase mortality among chronic disease patients, and exacerbate staffing shortages, with burnout rates remaining high. This underscores the need for robust and redundant systems to handle multiple crises.

Recommendations for Resilience

To build a resilient critical care system, the following recommendations address identified gaps and leverage lessons learned:

- Infrastructure Development:

- Scalable Facilities: Invest in flexible ICU designs with expandable bed capacities and real-time bed tracking systems.

- Critical Care Networks: Strengthen regional and national networks for resource sharing and patient transfers, particularly in underserved areas. The Hub and Spoke model can optimize critical care delivery by linking tertiary hubs with community spokes.

- Rural Focus: Address rural disparities through targeted investments in ICU infrastructure and telemedicine.

- Supply Chain Resilience: Enhance supply chain planning to ensure adequate stockpiles of ventilators, oxygen, and PPE, using IT solutions for monitoring.

- Workforce Capacity:

- Training Programs: Develop virtual and simulation-based training to maintain education during crises.

- Learning Networks: Support networks like CRIT CARE ASIA and AFROHUN to facilitate data sharing, quality improvement, and collaborative research. To replicate the SEAOHUN/AFROHUN model of University networks in critical care skills training, use an experiential learning cycle. Start with theoretical modules covering essential critical care concepts (e.g., ventilator use, sepsis protocols), delivered by an interdisciplinary team. Follow up with hands-on simulations and supervised clinical placements, where learners engage in real or simulated ICU scenarios, such as managing ventilated patients.

- Mental Health Support: Implement flexible scheduling and mental health resources to combat burnout and retain staff. Providing access to mental health services, including counseling, Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs), and mindfulness resources, can help employees manage stress and build resilience.

- Rapid Training Frameworks: Develop in-training frameworks for redeployed staff to ensure rapid skill acquisition.

- Research and Innovation:

- Sustained Research: Increase government spending on relevant clinical research with low dependence on external resources. Identify avenues of private sector investment in research. Promote platform trials and integrate research into clinical practice for rapid translation of findings. Develop a system of screening for relevance but decrease barriers to science, e.g., bureaucratic processes that go beyond ethical assessments and hinder initiation of research.

- Research Continuity: Develop study protocols to protect non-pandemic research during crises.

- Policy and Funding:

- Sustained Investment: Advocate for long-term funding for public health infrastructure and workforce development.

- Global Agreements: Strengthen the WHO pandemic treaty to ensure equitable access to critical care resources and foster international cooperation. While a lot of focus is on surveillance and detection of the disease, one of the strongest pillars of the response systems for infectious disease outbreaks is the critical care infrastructure and service delivery which is unfortunately missed in the public health deliberations.

- Addressing Translation Challenges:

- Community Capacity Building: Invest in training and equipping community hospitals to stabilize critical care patients initially. Proper stabilization and early treatment initiation plays a big role in ensuring decrease in morbidity and mortality.

- Efficient Transfer Systems: Develop robust systems for transferring patients from community to tertiary centers, minimizing risks and delays. Studies highlight the importance of coordinated transfer centers, as explored in a 2024 study, to improve clinical outcomes by facilitating transfers to hospitals with appropriate resources and expertise. A centralized system, acting as a single point of contact, can streamline communication between various stakeholders, including Emergency Medical Services and hospitals.

- Integrated Care Pathways: Create pathways to ensure continuity of care between community and tertiary levels through standardized crisis-specific care protocols, coordinated care plans, and drills for continuity of care during disruptions.

The following matrix suggests few actionable recommendations for resilience and impact:

| Recommendation (and associated Resilience elements) | Key Actions | Examples Steps | Expected Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scalable Facilities (Robustness, Redundancy) | Flexible ICU designs, real-time bed tracking | Modular ICUs that expand quickly. Convertible spaces (e.g., low frequency use rooms to ICUs). Develop standards for modular ICU designs. Conduct regular scalability drills. | Improved surge capacity, better resource allocation |

| Critical Care Networks (Redundancy, Rapidity) | Hub and Spoke model, regional collaboration | Agreements for patient transfers between hospitals. Centralized bed/resource tracking. Establish mutual aid agreements with hospitals. Implement a real-time resource platform. | Enhanced access, efficient patient transfers |

| Supply Chain Resilience (Robustness, Redundancy) | Stockpile management, IT monitoring | Diversified suppliers for ventilators/PPE. Stockpiles of essential supplies. Conduct supply chain vulnerability audits. Maintain strategic reserves of supplies. | Reduced shortages, timely resource availability |

| Workforce Training (Rapidity, Resourcefulness) | Virtual/simulated training, rapid training frameworks | Simulation-based crisis training. Cross-training staff for multiple roles. Develop a standardized crisis training curriculum. Implement regular simulations. | Increased staff preparedness, reduced skill gaps |

| Mental Health Support (Robustness) | Flexible scheduling, mental health resources | Regular mental health check-ins for workers. Peer support networks. Establish a mental health support program. Train managers to recognize burnout. | Lower burnout, higher staff retention |

| Learning Networks (Resourcefulness, Rapidity) | Data sharing, quality improvement initiatives | Online platforms for sharing best practices. Regular crisis management webinars. Create a knowledge-sharing platform. Organize quarterly learning sessions. | Continuous learning, improved outcomes |

| Global Agreements (Resourcefulness) | Strengthen WHO treaty provisions | Participation in international stockpiling. Bilateral resource-sharing agreements. Negotiate international resource-sharing agreements. Join global health security initiatives. | Equitable resource access, global cooperation |

| Community Capacity (Robustness) | Training, equipment for community hospitals | Training community health workers in emergency care. Community emergency plans. Implement community training programs. Create local emergency response teams. | Better initial care, reduced transfer needs |

| Transfer Systems (Rapidity) | Robust logistics, communication protocols | Real-time data for optimizing patient transfers. Interoperable health info systems. Invest in real-time patient tracking tech. Standardize transfer protocols. | Safer, faster patient transfers |

| Integrated Pathways (Resourcefulness) | Seamless care coordination | Standardized crisis care protocols. Coordinated care plans for continuity. Develop crisis-specific care pathways. Conduct regular coordination drills. | Improved continuity, patient outcomes |

The 4R framework includes Robustness (ability to withstand shocks), Redundancy (excess capacity or backups), Rapidity (quick response and recovery), and Resourcefulness (creative adaptation during crises).

Additional innovative solutions prioritizing service delivery resilience, ensuring critical care systems can maintain functionality and adaptability during crises through technology-driven and organizationally creative approaches.

| Recommendation | Examples | Actionable Steps |

|---|---|---|

| AI/ML-Driven Triage System (Robustness, Rapidity) | AI/ML algorithms prioritizing patients based on real-time vitals and predictive outcomes. Dynamic staff allocation based on AI insights. | Deploy AI triage tools in emergency departments. Train staff to interpret and act on AI recommendations. |

| Peer-to-Peer Care Network (Redundancy, Resourcefulness) | Real-time digital platform for hospitals to share staff or expertise. Telemedicine hubs connecting facilities for overflow support. | Build a secure platform for resource sharing. Establish protocols for telemedicine collaboration. |

| Predictive Surge Analytics (Rapidity, Redundancy) | Machine learning (ML) models forecasting patient surges using local health data. Automated alerts for preemptive staffing adjustments. | Integrate predictive analytics with hospital systems. Set up automated notification workflows. |

| VR/AR Rapid Training (Robustness, Resourcefulness) | Virtual reality simulations for upskilling staff on rare procedures. Augmented reality guides for real-time procedure support. | Develop VR/AR training modules for crisis scenarios. Equip staff with AR-enabled devices for on-the-job aid. |

| Crowdsourced Innovation Hub (Resourcefulness) | Online platform where healthcare workers globally share crisis solutions. AI curates and ranks ideas for rapid adoption. | Launch a crowdsourcing portal for healthcare ideas. Use AI to filter and promote actionable solutions. |

| Mental Health AI Monitoring (Robustness) | AI tools analyzing staff speech and behavior for burnout detection. Virtual reality relaxation modules for stress relief. | Implement AI monitoring with opt-in consent. Provide VR relaxation stations in break areas. |

| Autonomous Patient Transfers (Rapidity) | Drone or autonomous vehicle fleets for inter-facility patient movement. Real-time routing optimized by weather and traffic data. | Pilot autonomous transfer systems in urban areas. Integrate real-time data feeds into logistics. |

| Dynamic Care Pathways (Robustness, Rapidity) | Clinical decision support systems using Machine learning suggesting alternative treatments when resources are scarce. Digital twins simulating patient outcomes for care optimization. | Develop ML models for care path adaptation. Use digital twins to test and refine protocols. |

While the above recommendations are conceptual, extensive studies need to be undertaken to understand the relevance and cost efficiency of these proposed models.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic served as a stark reminder of the critical importance of a robust and resilient critical care infrastructure and workforce. Five years on, while progress has been made, significant vulnerabilities persist. The continued strain on healthcare systems from re-emerging variants and other outbreaks underscores the need for sustained focus and strategic investment. Leveraging the 4R resilience framework—Robustness, Redundancy, Rapidity, and Resourcefulness—provides a clear roadmap for future preparedness. Moving forward, efforts must concentrate on scalable infrastructure (flexible ICU designs, critical care networks, and addressing rural disparities), workforce strengthening (through continuous training, mental health support, and rapid upskilling), and fostering research and innovation (sustaining studies and integrating new technologies like AI and VR/AR). Furthermore, it is essential to ensure equitable access to critical care by building capacity at the community level and establishing efficient patient transfer systems.

The lessons from COVID-19 demand a shift from reactive crisis management to proactive resilience building. By implementing the comprehensive recommendations outlined in this review, and embracing innovative solutions, healthcare systems can better withstand future health crises, ensuring high-quality, accessible critical care for all. The ongoing challenges highlight that preparedness is not a one-time effort but a continuous journey of adaptation and improvement.

References

- Wurmb T, Scholtes K, Kolibay F, et al. Hospital preparedness for mass critical care during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Crit Care. 2020 Jun 30;24(1):386. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03104-0. PMID: 32605581; PMCID: PMC7325193.

- Suntharalingam G, Handy J, Walsh A. Regionalisation of critical care: can we sustain an intensive care unit in every hospital? [published correction appears in Anaesthesia. 2014 Nov;69(11):1298]. Anaesthesia.

- Hermann B, Benghanem S, Jouan Y, Lafarge A, Beurton A; ICU French FOXES (Federation Of eXtremely Enthusiastic Scientists) Study Group. The positive impact of COVID-19 on critical care: from unprecedented challenges to transformative changes, from the perspective of young intensivists. Ann Intensive Care. 2023;13(1):28. Published 2023 Apr 11. doi:10.1186/s13613-023-01118-9

- Rabinowitz R, Drake CB, Talan JW, et al. Just-in-Time Simulation Training to Augment Overnight ICU Resident Education. J Grad Med Educ. 2024;16(6):713-722. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-24-00268.1

- Duffy JR, Vergara MA. Just-in-Time Training for the Use of ICU Nurse Extenders During COVID-19 Pandemic Response. Mil Med. 2021;186(12 Suppl 2):40-43. doi:10.1093/milmed/usab195

- Papazian, L., Hraiech, S., Loundou, A. et al. High-level burnout in physicians and nurses working in adult ICUs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med 49, 387-400 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-023-07025-8

- Wahlster S, Sharma M, Çoruh B, et al. A Global Survey of the Effect of COVID-19 on Critical Care Training. ATS Sch. 2021;2(4):508-520. Published 2021 Oct 21. doi:10.34197/ats-scholar.2021-0045BR

- Pairo-Castineira E, Clohisey S, Klaric L, et al. Genetic mechanisms of critical illness in COVID-19. Nature. 2021;591(7848):92-98. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-03065-y

- Angus DC, Berry S, Lewis RJ, et al. The REMAP-CAP (Randomized Embedded Multifactorial Adaptive Platform for Community-acquired Pneumonia) Study. Rationale and Design. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(7):879-891. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202003-192SD

- RECOVERY Collaborative Group, Horby P, Lim WS, et al. Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):693-704. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2021436

- Pattison NA, O’Gara G, Cuthbertson BH, et al. The legacy of the COVID-19 pandemic on critical care research: a descriptive interview study. J Intensive Care Soc. 2024;26(1):53-60. doi:10.1177/17511437241301921

- World Health Organization. The pandemic treaty: a milestone, but with persistent concerns. Lancet. 2025;405(10236):1456-1462.

- Government of India. PM-Ayushman Bharat Health Infrastructure Mission. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2021. Accessed June 19, 2025. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1764901

- Government of India. Operational Guidelines of Pradhan Mantri Ayushman Bharat Health Infrastructure Mission. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2021. Accessed June 1, 2025. https://nhsrcindia.org/sites/default/files/FINAL%20PM-ABHIM__15-12-21.pdf

- Ramesh T, Yu H, Chen L, et al. Improving rural intensive care infrastructure in the United States: a strategy to avoid further ICU closures. Lancet Respir Med. 2024;12(4):268-269.

- Mirchandani P. Health Care Supply Chains: COVID-19 Challenges and Pressing Actions. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(4):300-301. doi:10.7326/M20-1326

- Aiken, Linda H et al. Nurse staffing and education and hospital mortality in nine European countries: a retrospective observational study, The Lancet, Volume 383, Issue 9931, Feb 26, 2014, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62631-8

- Vogt KS, Simms-Ellis R, Grange A, et al. Critical care nursing workforce in crisis: A discussion paper examining contributing factors, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and potential solutions. J Clin Nurs. 2023;32(19-20):7125-7134. doi:10.1111/jocn.16642

- Braddock A, Malm-Buatsi E, Hicks S, et al. Healthcare Workers’ Perceptions of On-Site Childcare. J Healthc Manag. 2023;68(1):56-67. doi:10.1097/JHM-D-22-00007

- CRIT CARE ASIA. Establishing a critical care network in Asia to improve care for critically ill patients in low- and middle-income countries. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):608. Published 2020 Oct 15. doi:10.1186/s13054-020-03321-7

- Sood B, Srivastava V, Mohanty N et al. Addressing the Urgency and Magnitude of the COVID-19 Pandemic in India by Improving Healthcare Workforce Resilience, Global Perspectives of COVID-19 Pandemic on Health, Education, and Role of Media (pp.25-44), August 2023, doi: 10.1007/978-981-99-1106-6_2.

- Ward P. The hub and spoke model of intensive care regionalisation: hoping the wheels don’t come off. Anaesthesia. 2015;70(1):110. doi:10.1111/anae.12966

- Ssekamatte T, Isunju JB, Nalugya A, et al. Using the Kolb’s experiential learning cycle to explore the extent of application of one health competencies to solving global health challenges; a tracer study among AFROHUN-Uganda alumni. Global Health. 2022;18(1):49. Published 2022 May 12. doi:10.1186/s12992-022-00841-5

- Watanabe, T., Ohsugi, K., Suminaga, Y. et al. An evaluation of the impact of the implementation of the Tele-ICU: a retrospective observational study. J Intensive Care 11, 9 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-023-00657-4

- Dahn CM, Maheshwari S, Stansky D, et al. Unexpected ICU Transfer and Mortality in COVID-19 Related to Hospital Volume. West J Emerg Med. 2022;23(6):907-912. Published 2022 Nov 1. doi:10.5811/westjem.2022.8.57035

- Cox C, Rudowitz R et al, Potential Costs and Impact of Health Provisions in the Build Back Better Act, Health Costs, KFF Brief, Published: Nov 23, 2021, https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/potential-costs-and-impact-of-health-provisions-in-the-build-back-better-act/

- Wahlster S, Sharma M, Çoruh B, et al. A Global Survey of the Effect of COVID-19 on Critical Care Training. ATS Sch. 2021;2(4):508-520. Published 2021 Oct 21. doi:10.34197/ats-scholar.2021-0045BR

- Shiri R, Turunen J, Kausto J, et al. The Effect of Employee-Oriented Flexible Work on Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10(5):883. Published 2022 May 10. doi:10.3390/healthcare10050883

- de Lusignan, Simon et al. Sleeper frameworks for Pathogen X: surveillance, risk stratification, and the effectiveness and safety of therapeutic interventions. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, Volume 24, Issue 7, e417 – e418. Published June 3, 2024. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00352-9

- Güner R, Hasanoğlu I, Aktaş F. COVID-19: Prevention and control measures in community. Turk J Med Sci. 2020;50(SI-1):571-577. Published 2020 Apr 21. doi:10.3906/sag-2004-146

- Henry MB, Funsten E, Michealson MA, et al. Interfacility Patient Transfers During COVID-19 Pandemic: Mixed-Methods Study. West J Emerg Med. 2024;25(5):758-766. doi:10.5811/westjem.20929

“`