S. aureus Superantigens: Key Roles in Human Diseases

The Importance of S. aureus Superantigens in Human Diseases

Patrick M. Schlievert, PhD

University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Iowa City, IA, United States

Email: [email protected]

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 July 2025

CITATION Schlievert, PM., 2025. The Importance of S. aureus Superantigens in Human Diseases. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(7). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i7.6729

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i7.6729

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Objective: Staphylococcus aureus is a common and important cause of a myriad of serious human infections. The organisms superantigens toxins are causes of many of these diseases. This review discusses the physicochemical and biological properties of superantigens, their roles in human diseases, assays for antibodies against the superantigens, and assays for the superantigen proteins and DNA.

Results: Staphylococcal superantigens include toxic shock syndrome toxin-1, staphylococcal enterotoxin serotypes A to E and G, and staphylococcal superantigen-like serotypes I and K to X. The first human cells staphylococcal superantigens interact with are epithelial cells through the immune co-stimulatory molecule, CD40, and keratinocytes through CD40 and gp130. After penetration into the circulation, superantigens are potent pyrogens, they amplify the lethal effects of Gram-negative endotoxin, and they cause massive T lymphocyte proliferation and macrophage shock syndrome toxin-1 and enterotoxins B and C, are important causes of toxic shock syndrome and necrotizing pneumonia after influenza, and are highly associated with infective endocarditis, atopic dermatitis, diabetes mellitus type 2, bullous pemphigoid, numerous autoimmune diseases, and certain types of cancer. Patients who develop serious infections as a result of sero-susceptibility to superantigens do not develop immunity to the toxins as determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. Commercially-available intravenous immunoglobulins have high titers of protective antibodies. Superantigens associated with human diseases can be assayed for by combinations of antibody-based assays (in body fluids other than blood, and on skin) and polymerase chain reaction, both for detection and quantification. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction has recently been used to demonstrate superantigen DNA in human urine and blood.

Conclusion: Staphylococcal superantigens are known causes of human diseases. Additionally, the proteins are associated with many other human diseases where they have been conclusively shown to be causative. We know how to determine antibodies against superantigens, and we have assays to detect and quantify the superantigens.

Implications: Our ability to measure antibodies to superantigens and detect and quantify the superantigens in humans have allowed us to show that staphylococcal superantigens are important causes of serious infections. Furthermore, these reagents have allowed us to associate staphylococcal superantigens with many other common infections and conditions. This may lead to studies to vaccinate humans against toxoids of at least the three major superantigens, toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 and enterotoxins B and C.

Keywords

Staphylococcus aureus, superantigens, toxic shock syndrome, staphylococcal infective endocarditis, staphylococcal pneumonia, atopic dermatitis, diabetes mellitus type 2, bullous pemphigoid.

Introduction

This review will focus primarily on the superantigen toxins produced by Staphylococcus aureus, providing a discussion of their physicochemical properties and mechanisms of action, diseases associated with and caused by them, and assays for the proteins and antibodies to neutralize the proteins. Staphylococcal superantigens include the staphylococcal enterotoxin (SE) serotypes A-E and G, SE-like (SEl) superantigens H-X, and toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 (TSST-1).

Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A streptococci; β-hemolytic streptococci) are among the most potent and common pathogens worldwide. For example, the United States National Institutes of Health recently indicated Group A streptococci are the second most common cause of infection-related deaths in the world, second only to tuberculosis, and more common than deaths due to malaria. In the United States, S. aureus is the most significant cause of serious bloodstream infections, and my laboratory has suggested that as many as 50,000 children have succumbed to post-influenza toxic shock syndrome since we described the infection in 1987. Bacterial superantigens are required for these two pathogens to cause serious human infections. Yet, they remain profoundly understudied as related to human diseases.

Superantigen toxins are a large family of pyrogenic (fever-inducing) toxins produced almost exclusively by S. aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes, though occasional coagulase-negative staphylococci and other β-hemolytic streptococci produce superantigens.

Superantigen Physicochemical and Biological Properties

SEs were originally defined by their abilities to cause emesis and diarrhea, and as being the most common causes of food poisoning. TSST-1 was separated from the SEs because of its lack of emetic activity, because of its lack of cysteine amino acids required for emesis, and because it is the most common cause of TSS. TSST-1 was formerly called pyrogenic exotoxin serotype C and later SE serotype F; both of these names have been retired from use as a result of an international meeting on TSS in 1984 in Madison, WI in the United States. Drs. Schlievert and Bergdoll agreed to the name TSST, and the remainder of the symposium attendees added the dash one in case there were other TSSTs. The only other TSST, that has been found since 1984, is TSST-ovine, which is biologically active in sheep but is inactive in humans. The SEls are the newcomers in the family, all having superantigen activity, most sharing varying degrees of primary amino acid sequence similarity to SEs, but none having emetic/diarrheagenic activity, or not having been tested for these activities. Incidentally, TSST-1 lacks primary amino acid sequence similarity with the SEs and SEls. However, all superantigens have a shared three-dimensional structure, with TSST-1 having the base structure. All are approximately 30 x 50 Angstroms in size. To put this in perspective, 30 Angstroms is approximately 1/10,000 the diameter of a single S. aureus cell. SEs have a cystine loop, not shared by other superantigens, that is needed for their abilities to cause emesis and diarrhea. SEls have an extra loop at the top of the molecules (in the standard view), not shared with other superantigens, that facilitates interaction with T lymphocytes. Nearly all superantigens, whether staphylococcal or streptococcal, have 15 amino acids positioned in space in the same molecular place, which then guide folding of the rest of the amino acids around them to form the common structure.

Superantigens are secreted proteins of 20,000 to 30,000 molecular weight. They are synthesized from genes with signal peptides, that lead the primary amino acid sequences through the bacterial surface, wherein mature superantigens are then immediately folded into the three-dimensional shape outside the bacterial cell. The signal peptide is cleaved from the active superantigens after initiation of transit. No intact superantigens exist within staphylococcal cells, although superantigen molecules may remain associated with the carotenoid (gold) pigments on S. aureus surfaces, the pigment which gives S. aureus its species name and gold-colored colonies on Petri plates.

Nearly all staphylococcal superantigens are encoded on variable genetic DNA elements. This means that nearly all superantigens are encoded on bacteriophages (SEA), plasmids (SED), or pathogenicity islands (most of the rest except SEl-X, which is present in all S. aureus though variably expressed). For example, TSST-1 is present on pathogenicity islands 1 and 2. These pathogenicity islands were at one time bacteriophages, but because of DNA deletions and recombinations, they have become trapped in the bacterial chromosomes. Usually, multiple superantigens are encoded on one pathogenicity island. For example. TSST-1 is encoded on a pathogenicity island with SEl-L, SEl-K, and SEl-Q.

All superantigens are highly resistant to proteases, which allows the SEs to survive the gut long enough to cause vomiting and diarrhea. All superantigens are highly resistant to heat and drying, for example boiling for one hour and storage dry on laboratory benches for a year, respectively. Finally, all are highly resistant to acids, such as bleach, with lye as the most effective way to eliminate them from surfaces. The tryptophan amino acids in the molecules are required for activities and are destroyed by lye. These resistance properties plus ease of production of SEs make the SEs (serotypes A-E) select agents of bioterrorism as defined by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Not all superantigens are produced in the same quantities. SEA is easily produced in amounts of 1-2 µg/ml, SEB and SEC in amounts of 40-80 µg/ml, and TSST-1 in amounts of 5-20 µg/ml in broth cultures, dependent on staphylococcal strains. These numbers can be multiplied by 1000 when the same S. aureus strains are cultured in biofilms. This means that SEs B and C can be produced in amounts up to 50 mg/ml in biofilms. Incidentally, biofilms are simply thin-films of the staphylococci cultured on skin or mucous membrane surfaces or on cellulose acetate dialysis tubing in the laboratory. Most of the total proteins secreted by TSS S. aureus are superantigens.

Because of this and their impressive stability, these superantigens do not require weaponization or purification to be used as bioterrorism agents. Based on many studies in rabbits, non-human primates, and even humans, amounts of superantigens as low as 0.1 µg can be fatal when administered intra-pulmonary or intravenously. Much lower doses (in the nanogram range) are sufficient to cause emesis and diarrhea when SEs are administered orally. Finally, superantigens in the picogram range cause a syndrome we call red eye syndrome which is self-explanatory. This red eye syndrome can be sufficient to require affected persons not to study superantigens. In such individuals, even using the superantigens under biosafety cabinets is insufficient to assure non-sensitization to red eye syndrome. We believe the red eye syndrome depends on hypersensitivity so repeated exposure is necessary.

The remaining superantigens are produced in amounts in the low nanogram range. This observation makes it more likely than not that the remaining large number of superantigens are colonization factors as opposed to disease-causing agents. This has been most clearly shown in a rabbit model of human disease, where superantigens, such as SElI, M, N, and O lead to colonization, whereas TSST-1 produced by the same strains leads to serious overt disease.

As originally described, superantigens were called pyrogenic toxins. This is because they are the most potent pyrogens known. The mechanism of fever production is two-fold: 1) direct stimulation of the hypothalamus to produce prostaglandin E2, and 2) indirect action through induction of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) from macrophages, with subsequent IL-1β stimulation of the hypothalamus to produce prostaglandin E2. Prostaglandin E2 alters the human body temperature set point with resultant downstream fever.

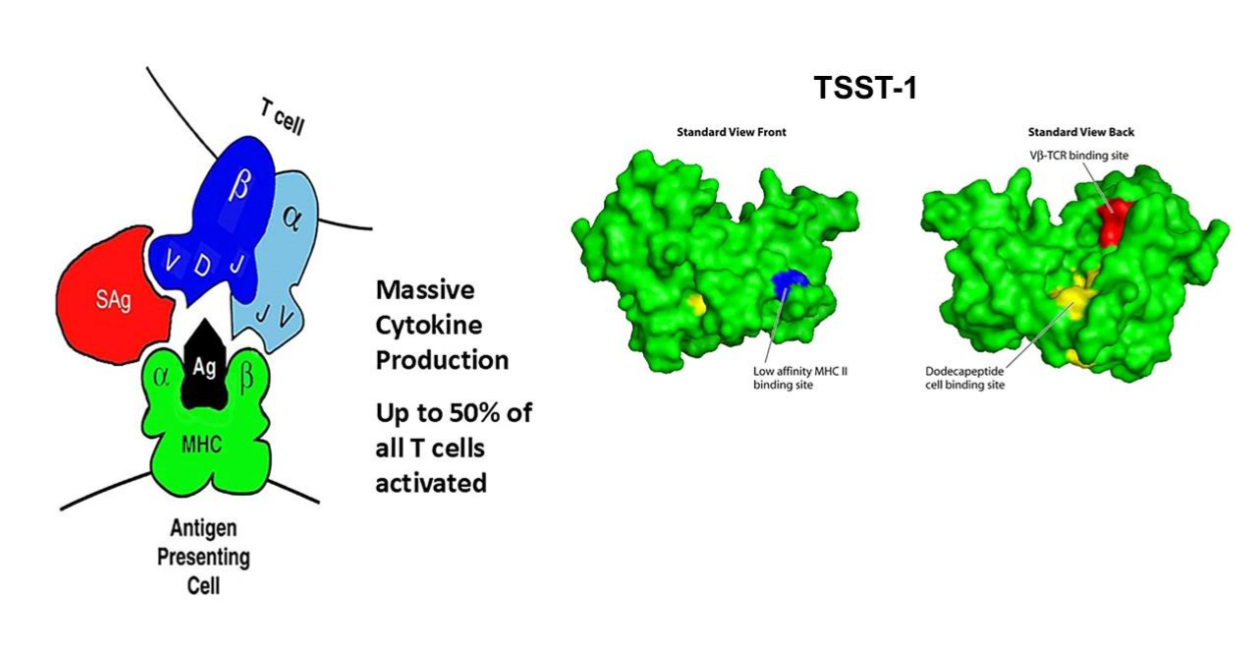

The name superantigen was given to this large family of proteins by Marrack and Kappler because of the unique way pyrogenic toxins stimulate T lymphocyte proliferation; this catchy name caught on and has been retained for the family. Both CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes proliferate in response to superantigen challenge, with the major effects requiring simultaneous engagement of antigen-presenting cells. This suggests the dominant interactions, at least initially are among antigen-presenting cells and CD4+ T cells. T lymphocyte proliferation depends on superantigens binding to α- and/or β-chains of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules and the variable part of the β-chain of T lymphocyte receptors (VβTCRs). No superantigen activates all CD4+ T lymphocytes. Rather, each superantigen may activate up to 50% of CD4+ T lymphocytes, dependent on the composition of the variable part of the TCR β-chain, but not dependent on specific antigen recognition. For example, the approximate percentage of Vβ2TCRs on T lymphocytes in humans is nearly 10%, but in active cases of menstrual TSS, TSST-1 causes proliferation of these Vβ2TCR-containing T cells to become 60-70% of all T cells; Vβ2TCR+ T cells is the only T cell subpopulation that is stimulated by TSST-1. The consequence of this massive T lymphocyte stimulation is also tremendous over-activation of macrophages, with both T cell and macrophage production of cytokines, including interleukin-1β (causing fever), tumor necrosis factors-α and -β (causing hypotension due to capillary leak), and interleukin-2 and interferon gamma (minimally causing macular erythroderma). TSS is the disease where the term cytokine storm was first used. While the most obvious observation of superantigen activities is dominated by production of T helper1 lymphocyte and macrophage cytokines, chronic T cell activation or simply genetic differences among humans leads to dominance by T helper2 cells and their cytokines, seen most often as an anaphylactic form of TSS or the presence of an atopic dermatitis rash as opposed to the standard scarlet fever-like rash.

For superantigens to gain access to the circulation to exert their pro-inflammatory effects, the proteins must first interact with epithelial cells and keratinocytes. Studies have shown that human vaginal epithelial cells have the immune co-stimulatory molecule CD40 as their receptor for superantigens, with TSST-1 ten times better able to interact than other superantigens. The interaction of human keratinocytes with superantigens is more complicated, requiring both CD40 and other receptor molecules, including gp130. gp130 also constitutes a receptor on adipocytes for superantigens. The downstream effect of the interaction of superantigens with epithelial cell and keratinocyte receptors is harmful chemokine production with loosening of the barrier function of these cells and facilitating greater superantigen access to the circulation. We refer to this process as outside-in-signaling to cause disease. The consequence of superantigen interaction with adipocytes is harmful pro-inflammatory adipokine production.

Another important property shared by all superantigens is the ability to amplify the lethal effects of Gram-negative bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS; endotoxin) by as much as one-million-fold. S. aureus is Gram-positive and thus does not contain LPS. However, humans are heavily colonized by Gram-negative bacteria, particularly in the large intestine, where it is estimated there are one million Escherichia coli per gram of feces. In healthy persons, LPS leaks across the gut constantly to be cleared immediately by the liver, in this way preventing endotoxin shock. However, many agents, including superantigens, chronic alcoholism, carbon tetrachloride, heptotoxic viruses, and the mushroom poison α-amanitin, interfere with this normal endotoxin clearance mechanism, leading to systemic LPS spill-over and consequent increased susceptibility to shock and death. For superantigens, the combined effects of superantigens plus LPS, lead to even more massive production of TNF-α from macrophages and thus more massive capillary leak and shock. It has been proposed that the hypotension and shock seen in TSS result in total or in part from this LPS-enhancement mechanism.

One other property of superantigens merits discussion, namely the SE emetic and diarrhea activity, which appear separable from superantigenicity. These activities are restricted to the SEs, where the toxins are both stable to gut degradation and have the cystine loop of amino acids. The ability of SEs (A-E and G) to cause emesis and diarrhea depends on their crossing the gut and inducing prostaglandins upon interaction with the Vagus nerve.

Superantigen Causation of Human Diseases

TOXIC SHOCK SYNDROME (TSS)

S. aureus is well-known to be the cause of staphylococcal TSS. There are two forms of staphylococcal TSS, menstrual and non-menstrual. TSS is defined by high fever, hypotension progressing to shock and death in the most severe cases, a macular erythroderma upon repeated exposure to superantigens, peeling of the skin upon recovery, and a set of variable multi-organ changes, most often seen initially as flu-like vomiting and diarrhea, but including many other metabolic changes. Probable TSS is the same illness except missing one defining property. Probable TSS is more common than fully-defined TSS, with either high fever or rash the most often missing symptoms. We have proposed with Dr. Jeffrey Parsonnet the use of toxin mediated disease when more than one defining criteria are missing.

Menstrual TSS is defined as occurring during or with two days of onset or completion of the menstrual period. Nearly 95% of initial menstrual TSS cases are associated with tampon use, with risk increasing with rise in tampon absorbency. The association with tampon use is clearly due to oxygen introduction vaginally into a typically anaerobic environment. Oxygen is an absolute requirement for production of TSST-1. During menstruation, when S. aureus is present, the organisms peak on day 2-3, one day preceding onset of most cases of menstrual TSS. In regions of the world where menstrual TSS is highest, S. aureus numbers vaginally on day 2 of menstruation may reach 10^10 or higher. In the presence of oxygen from certain tampons, combined with carbon dioxide, protein, low glucose, and 37°C temperature, TSST-1 is produced, crosses the vaginal mucosa into the circulation, and causes the symptoms of TSS.

There is an important but incompletely understood aspect of menstrual TSS. It is known that development of neutralizing antibodies to TSST-1 happens as a function of age, with no infants of 3 months of age having protective neutralizing antibodies, but 80% of 12-year-olds having protective antibodies. It is the 20% who lack neutralizing antibodies that develop menstrual TSS. It is completely unknown why those 20% have not developed antibodies. It is hard to imagine that pre-teens have not encountered TSST-1 producing S. aureus since approximately 10% of all S. aureus strains produce the superantigen, and S. aureus infections are exceptionally common. It appears, that through some mechanism, the 20% of persons lacking protective antibodies are genetically unresponsive or hyper-responsive, with this latter over-active response causing serious disease and consequent prevention of protective antibody responses. Additionally, it is well-known that young women who develop menstrual TSS, with age 14 being the most common in 2025, will develop recurrences if they continue to use tampons. Even young women, who never use tampons after the first episode, will develop recurrences, indeed as many as 40%. I am aware of young women who have developed six episodes of menstrual TSS, requiring admission to intensive care units, when they used tampons only during the first episode. It is simply not clear why these young women develop recurrences. Likewise, 5% of women will develop menstrual TSS, despite not ever using tampons. How this happens is unclear.

There have been investigators who suggest that non-absorbent vaginal products, such as menstrual cups, may be associated with menstrual TSS. However, menstrual cups unlike tampons do not have fibers to trap oxygen. We have shown that it is not oxygen upon insertion of medical devices vaginally that leads to TSST-1 production, but rather, oxygen trapped within tampon fibers. This is important to state since as many as 25% of women in some European countries use menstrual cups during menstruation. I have published that these menstrual cup-associated cases may simply represent the background 5% of women who will develop TSS, without regard to use of medical devices to control menstrual flow.

It remains clear even today that the vast majority of menstrual TSS cases are associated with tampon use. For this reason, women are informed not to use tampons in order to reduce their risk as much as possible, but if they choose to use tampons, use those of lowest absorbency to control menstrual flow, and change the tampons in 4 to 8-hour intervals. Alternating tampons and menstrual pads may reduce the risk.

I have been asked if emergency use of a single cosmetic sponge will lead to menstrual TSS. I am not aware of even one case associated with the use of one such sponge.

Many physicians ask me where and when TSST-1 producing S. aureus arose worldwide. The strain that produces TSST-1 was present prior to the mid-1970s, when the highest absorbency tampons began being marketed. However, our studies have shown that TSST-1 producing S. aureus emerged in 1971, prior to the marketing of the highest absorbency tampons, with the peak occurring in 1975-1976. The strain remains common even today likely because TSST-1 production gives the S. aureus a selective infection advantage, compared to other strains. However, we do know that TSST-1 was present in S. aureus as far back as 1928, where we showed that the Bundaberg (Australia) S. aureus strain produced the superantigen. This strain killed 12 of 21 children accidentally inoculated with bacteria-contaminated, anti-diphtheria antibodies. These children, and 6 other children, had the defining TSS symptoms.

I should now define what strain means for S. aureus. In the past, we defined strains or clones based on bacteriophage infection of the organisms. However, more recently S. aureus clonal groups are defined by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis types as devised by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; these are named USA100-USA1100. For example, TSST-1 strains used to be called phage groups 29, 52, or 29/52, but are now called USA200. SEB and SEC strains are called USA400. There are now even more molecular techniques to define the clonal groups, including multi-locus sequence types and SPA types (staphylococcal protein A types). I continue to use USA100-1100 typing as defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention because of the association of TSST-1 with USA200, SEl-X with USA300, and SEB and SEC with USA400.

Non-menstrual TSS may also be caused by strains of S. aureus, usually USA200-USA400 clonal groups. Non-menstrual TSS is caused by S. aureus strains that usually produce one or more of what I have defined as the big three superantigens: TSST-1, SEB, and/or SEC. Non-menstrual TSS may occur in any person who lacks antibodies to the causative superantigens (20% of persons older than 12 years of age lack antibodies to at least one of these three superantigens; none having antibodies as infants) and where the person is infected with the causative strain. Post-influenza pneumonia or other types of pneumonia due to S. aureus leads to the most common types of non-menstrual TSS. I have previously mentioned that as many as 50,000 children in the United States have succumbed to post-influenza TSS caused by TSST-1 since our description of this type of TSS in 1987. This is unconscionable for a supposedly developed Country, and which demonstrates how little attention is paid to finding a way to prevent this form of TSS.

SEPSIS AND INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS

S. aureus is a common cause of both significant sepsis and infective endocarditis. Our studies in a rabbit model of human infections show that both lethal sepsis and the defining vegetations (combinations of fibrin clots, red blood cells, and microbial colonies), seen in infective endocarditis, depend on production of superantigens. However, there are almost certainly other staphylococcal factors involved. It is important to note that TSS, sepsis, and infective endocarditis cannot be duplicated in murine models, but are accurately duplicated in rabbit models. Just as with TSS, lethal sepsis and infective endocarditis are most readily seen with TSST-1, SEB, and/or SEC producing strains of S. aureus. In the rabbit model, vaccination against TSST-1, SEB, and SEC protect rabbits from TSS, lethal sepsis, and infective endocarditis, as well as pneumonia. Superantigens are critical players in all potentially fatal S. aureus infections.

It is surprising to me that the biomedical community has not produced vaccines against serious S. aureus disease through use of toxoids of these three superantigens. To their credit, a group from Austria performed a vaccination safety study of a TSST-1 toxoid in humans. It would be ideal if follow-up studies could be done with toxoids of SEB and SEC, and these toxoids then used to vaccinate the entire populations. We and others have produced immunogenic but non-toxic mutants of each, so testing is all that stands in the way. I should also mention that we routinely vaccinate against diphtheria, whooping cough, and tetanus (DPaT) toxoids, so it seems reasonably simple to add these additional three toxoids to the DPaT toxoids.

ATOPIC DERMATITIS AND BULLOUS PEMPHIGOID

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, skin condition characterized by highly-itchy inflammation, leading to raw skin lesions. AD affects approximately 30 million people in the United States. AD has often been referred to as a scratch that leads to chronic itching, that in turn results in damaged skin. This scratch results either from genetic differences in people, for example alteration in filaggrin, or from minor chronic skin damage which intensely itches upon attempts at healing. Persons with damaged skin are nearly always ultimately colonized and infected with S. aureus. It is hypothesized that nasal colonization of infants, followed by food allergies, AD, and asthma through hypersensitivity. Studies have shown that all S. aureus strains associated with AD produce cytotoxins and superantigens. Production of high levels of cytotoxins is required for S. aureus skin infections. While cytotoxins act locally to kill immune cells and keratinocytes, superantigens act both locally and systemically to interfere with development of normal immunity. Additionally, once produced, superantigens have the ability to remain in affected mucosal and skin areas for up to months.

It has long been recognized that there is a strong IgE response to various antigens in AD patients. It is this strong T helper2 type antibody immune response that contributes importantly to the need for patients to scratch their itchy skin, thus leading to failure to heal, chronicity, and spread of infections. Why AD patients have a strong propensity for T helper2 skewing of their antibody responses, as opposed to T helper1 responses, is unclear.

In a recent study, we showed that a potentially severe form of AD, called eczema herpeticum, is highly associated with the superantigen TSST-1. In a later study, we showed, that when TSST-1 is present, S. aureus DNA and superantigen genes can be detected in the bloodstream of AD patients. For the majority of AD cases, the six membered superantigen group, called the enterotoxin gene cluster, is present. These six superantigens, SEG, SEl-I, SEl-M, SEl-N, SEl-N, SEl-O, and SEl-U, are encoded by S. aureus DNA on an operon. When TSST-1 is simultaneously present, the genes for these six superantigens can also be detected in the bloodstream. Incidentally, these same six superantigens are produced by the majority of S. aureus isolates from cystic fibrosis patients.

Bullous pemphigoid is a blistering disease of the elderly. It is considered an autoimmune disease where the target antigen is the hemi-desmosome proteins BP180 (also called Type XVII collagen) and BP230. BP 180 is the main target. Recently, we have shown that bullous pemphigoid patients are infected with USA200 strains of S. aureus, which produce the superantigen TSST-1. TSST-1 has also been demonstrated in the blisters of patients. Although TSST-1 may contribute to the blistering in bullous pemphigoid, the superantigen has no proteolytic activity to cleave BP180, the main autoimmune characteristic of the disease. It is well-known that USA200 strains of S. aureus are exceptionally-high producers of proteases, and these may contribute.

Because of the massive activation of T lymphocytes and macrophages by superantigens, it is not unreasonable to expect that the proteins will be associated with autoimmune diseases. Indeed, studies in animals and humans have already shown that multiple autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, guttate psoriasis, multiple sclerosis, and autoimmune enterocolitis may be induced by superantigens. From my personal experience, some cases of menstrual TSS have been initially diagnosed as acute-onset rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus. This is an area of Medicine that is in need of significant additional experimentation. I have many autoimmune diseases disappear if we vaccinate children with toxoids of TSST-1, SEB, and SEC.

Detection and Quantification of Antibodies Against Superantigens, and Superantigen Proteins and DNA

ASSAYS FOR ANTIBODIES TO SUPERANTIGENS

Superantigens are important causes of serious S. aureus diseases, whether TSS, pneumonia, sepsis, or infective endocarditis. The superantigens are also likely important drivers of atopic dermatitis and diabetes mellitus. In fact, 100% of S. aureus strains from human diseases produce one or more superantigens. For serious S. aureus diseases, one or more of the big three superantigens includes TSST-1 as the most potent of the group and SEB and SEC which are serologically cross-reactive with each other. Additionally, SEA is occasionally associated with serious S. aureus diseases, but this superantigen is the most common cause of staphylococcal food poisoning as a result of staphylococcal contamination of foods. The enterotoxin gene cluster of superantigens and related proteins are viewed as colonization factors. SEl-X is associated with USA300 strains and hemorrhagic pneumonia.

The most straightforward assay in humans related to superantigens is ELISA for protective antibodies. It has been shown that patients with TSS are sero-susceptible to superantigens, having only minimal or no detectable antibodies to the potential causative superantigens. We have tried to gain interest from companies in our quick Western spot test for the superantigens, but we have received no traction. This seems odd to me. Granted, there are not large numbers of young women developing menstrual TSS. However, just considering susceptibility to menstrual TSS, healthy young women and their parents would like to know the risk of developing TSS. This can then inform whether or not the young women would consider using tampons. In discussions with companies, I have offered to make the ELISA test available to physicians who would like their patients tested for antibodies. It is clear that patients who develop TSS do not make antibodies to the causative superantigen. This means they may develop recurrences. I also noted above that in some cases, the initial diagnoses of TSS were incorrect (acute-onset rheumatoid arthritis and others). These diagnoses were corrected after antibody titers and production of TSST-1, SEB, or SEC were determined; the patients lacked antibodies but had the causative superantigen present. Many of these same patients developed recurrent TSS.

It is important to note that commercial intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIGs), available for use in humans, have high titers of antibodies to all known superantigens. Additionally, many TSS patients have been treated with such antibodies. The importance of IVIG is highlighted by the following: A TSS patient was treated with a one-half dose of IVIG, along with antibiotics and blood pressure maintenance, and his condition improved. However, the patient relapsed. Upon treatment with the second one-half of the IVIG, the patient recovered. We have observed that the antibody titer of IVIG against each of the major TSS causes (TSST-1, SEB, SEC) is sufficient to give an adult patient a protective amount of antibodies.

ASSAYS FOR SUPERANTIGENS

My laboratory has tested over 8000 S. aureus strains, submitted to me for verification of TSS, whether menstrual or non-menstrual. The results of my assays indicate importantly that physicians are highly capable of identification of TSS since nearly all of the S. aureus strains produced one or more of TSST-1, SEB, or SEC. My laboratory has developed high-titer rabbit antibodies to these three superantigens. The levels of specific rabbit antibodies are high enough that my laboratory can grow the causative bacteria on Todd Hewitt agar plates, and when grown, we can add the rabbit antibodies to wells punched adjacent to the bacterial lawn, and then read the presence of a white precipitin arc between the antibodies and growing bacteria. The time this assay takes from start of growing the S. aureus to reading the result can be as short as 8 hours. As with antibody assays, I make this assay available to physicians who want their patients tested.

It is important to note that I have used this assay for patients suspected of having TSS, hemorrhagic pneumonia, sepsis, and infective endocarditis. My laboratory has also used a Western immunoblot spot test to quantify superantigens directly from skin swabs and tissue fluids, but not bloodstream. There are too many interfering factors in blood, combined with sequestration of superantigens on T lymphocytes in blood, that make blood assays not readily do-able. We have used direct superantigen quantification of superantigens on synovial fluids, sputum, and urine. In all of our assays, we use reaction with purified superantigens as controls. As an example of use, we assayed hip joint fluid from a TSS patient who had just succumbed to the hip joint infection. The patient had approximately 400 µg of SEB in the fluid. This is nearly 4000 lethal doses of SEB. The assay provided an explanation for why the person succumbed despite heroic efforts to save her.

There are commercial assays available to test for at least TSST-1 and SEB. The major assays I am aware of are variants of agglutination assays. My experience with these assays is that there are many interfering factors that reduce their value. As an example, I was contacted by a physician who thought he had two S. aureus strains associated with TSS but not producing TSST-1, as determined by a commercial agglutination assay. He sent the strains to me, and I found they both produced TSST-1. I should note that these two strains were also positive for the TSST-1 gene by polymerase chain reaction.

One additional type of assay we have developed recently involves quantitative polymerase chain reaction for superantigen gene detection and quantification in blood and urine. We have used this assay to assess potentially severe atopic dermatitis associated with TSST-1 and the enterotoxin gene cluster of six superantigens. We have also used the assay to do PCR on urine specimens. The primers for these assays are published.

For the Future

ROLE OF SUPERANTIGENS IN TOXIC SHOCK SYNDROME

We have learned a lot about TSS. However, there remain too many questions. For example: 1) Why do TSS patients lack antibodies to common superantigens by age 12, and why do they not develop antibodies after having TSS episodes?; 2) Why do we not have vaccine toxoids of TSST-1, SEB, and SEC? There have been many efforts to develop cell-surface vaccines against S. aureus. However, all of these have failed in human trials as we discuss in Nature Reviews Microbiology. We know that S. aureus aggregates to cause human diseases. By making antibodies against cell surface antigens, the organisms further aggregate and are better able to cause serious diseases, as shown in a rabbit model of infective endocarditis. Since toxins are not cell surface antigens, it is possible that vaccination against toxoids will be protective against serious diseases.

ROLES OF SUPERANTIGENS IN ADDITIONAL DISEASES

What is the full spectrum of S. aureus superantigen diseases? We know these proteins have roles in TSS, pneumonia, and sepsis/infective endocarditis. They appear to be drivers of atopic dermatitis. The possible causative roles of superantigens in diseases, including pneumonia, infective endocarditis, osteomyelitis, atopic dermatitis, diabetes mellitus, cystic fibrosis, and autoimmune diseases, merit additional investigation. I should note that there have not been studies of the role of superantigens in osteomyelitis. However, a commonly used strain to study this infection, called UAMS-1, is positive for TSST-1. Additionally, prior researchers studying septic arthritis, naturally occurring in mice, use a strain of S. aureus that produces TSST-1.

A short discussion of diabetes mellitus type 2 (DM2) is merited. It is known that there is a significant shift in the gut microbiome from Bacteroidetes to Firmicutes during development of DM2. A major pathogenic Firmicute is S. aureus. S. aureus skin infections in DM patients are exceptionally common. An estimated 30 million adults (9% of the United States population) have DM2, with an estimated 7 million not knowing they have the illness. Obesity and pre-DM2 increase S. aureus skin infections, approaching 100% when persons develop DM2. Additionally, many patients with DM develop ulcers, usually on the feet. Foot ulcers are exceptionally difficult to treat. They become infected with S. aureus producing superantigens. Infections by these organisms may lead to amputations and hypotension, shock, and death, almost certainly because of the superantigens produced.

We have evaluated nine persons with DM2 for the presence of S. aureus. Based on swabbing their palm, forearm and axillary skin surfaces, these persons have 10^11-10^13 S. aureus on their total skin surfaces, or up to 1 cubic inch of organisms. The isolated S. aureus produced the superantigens SEC and TSST-1. Two of the patients ultimately succumbed to septic infections due to the same S. aureus that colonized their skin. These infections may be from methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant S. aureus strains. We have also fulfilled all four of the requirements to show that S. aureus and its superantigens are causes of DM2.

I do not believe that S. aureus is the only cause of DM2. However, because of how common infections and colonization are with the organisms, it is likely S. aureus is an important driver, particularly because of immune dysregulation mechanisms. This possibility merits additional investigation.

In 1997, Jackow and colleagues showed a strong association of cutaneous T cell lymphoma with infection by USA200, TSST-1 producing S. aureus and Vβ2TCR T cell proliferation, the Vβ2TCR bound nearly exclusively by TSST-1. We have suggested that severe nasal polyposis can be induced by superantigens. Furthermore, when we published the gene dysregulation in primary human keratinocytes, the major pathways activated by TSST-1 and SEB included those that lead to various cancer types. What then is the full spectrum of superantigen diseases?

ASSAYS FOR ANTIBODIES AGAINST SUPERANTIGENS

Although assays are available in research settings for antibodies against TSST-1 in menstrual fluid. Such an assay could be developed, demonstrating protective antibodies (or lack of) against TSST-1, such that pre-teens or teens, who just begin menstruating and are having gynecology examinations for the first time, could have antibody titers measured on soiled menstrual pads. Such an assay would guide whether or not they should abstain from tampon use.

ASSAYS FOR SUPERANTIGEN PROTEINS AND DNA

Studies should continue to assay various body fluids for superantigen proteins and DNA so we can ultimately know the full spectrum of human diseases caused by the proteins.

Conclusions

Superantigens are an important and large family of exotoxins secreted by S. aureus. The superantigens, particularly TSST-1 and SEs B and C, are highly associated with many serious diseases. Indeed, it is likely that these exotoxins are the principal causes of death in affected patients. Our studies have shown that superantigens are required for S. aureus to cause human infections. At this time, we know that TSST-1 and SEs B and C are the causes of TSS, pneumonia, and infective endocarditis; the toxins are also likely drivers of atopic dermatitis and diabetes mellitus type 2. We do not know the full scale of superantigen diseases, but we need to know. Research should focus on both determining the full scope of superantigen diseases and on the development of toxoid vaccines to prevent the diseases.

My research laboratory has developed straightforward assays for antibodies to TSST-1 and SEs B and C, recognizing that these three staphylococcal superantigens cause serious human diseases. All humans at 3-4 months of age are susceptible to these three exotoxins. By age 12, 80% of humans have developed protective antibodies. I have previously proposed that significant numbers of children succumb to TSS associated with these exotoxins. Additionally, the 20% of susceptible humans by age 12 remain susceptible throughout their lives. There should be efforts to develop standardized assays for antibodies to these superantigens. Since we have toxoids to the three superantigens, it should be straightforward to develop antibody assays for commercial use. Similarly, there are sensitive assays available for accurate measurement of TSST-1 and SEs B and C produced by S. aureus in vitro and in human tissues. These should become routinely available for helping medical diagnoses.

Conflict of Interest Statement:

None.

Funding Statement:

None.

Acknowledgements:

None.

References:

- Spaulding, A. R. et al. Staphylococcal and streptococcal superantigen exotoxins. Clin Microbiol Rev 26, 422-447 (2013).

- McCormick, J. K., Yarwood, J. M. & Schlievert, P. M. Toxic shock syndrome and bacterial superantigens: an update. Annu Rev Microbiol 55, 77-104 (2001).

- Dinges, M. M., Orwin, P. M. & Schlievert, P. M. Exotoxins of Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Microbiol Rev 13, 16-34 (2000).

- Schlievert, P. M. & Davis, C. C. Device-associated menstrual toxic shock syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev 33, e00032-19 (2020).

- MacDonald, K. L. et al. Toxic shock syndrome. A newly recognized complication of influenza and influenzalike illness. Jama 257, 1053-1058 (1987).

- Bergdoll, M. S., Sugiyama, H. & Dack, G. M. Staphylococcal enterotoxin. I. Purification. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics 85, 62-69 (1959).

- Bergdoll, M. S. a. S., P.M. Toxic-shock syndrome toxin. Lancet ii, 691 (1984).

- Kreiswirth, B. N. et al. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature 305, 709-712 (1983).

- Schlievert, P. M., Shands, K. N., Dan, B. B., Schmid, G. P. & Nishimura, R. D. Identification and characterization of an exotoxin from Staphylococcus aureus associated with toxic-shock syndrome. J Infect Dis 143, 509-516 (1981).

- Bergdoll, M. S., Crass, B. A., Reiser, R. F., Robbins, R. N. & Davis, J. P. A new staphylococcal enterotoxin, enterotoxin F, associated with toxic-shock-syndrome Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Lancet 1, 1017-1021 (1981).

- Lee, P. K. et al. Nucleotide sequences and biologic properties of toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 from ovine- and bovine-associated Staphylococcus aureus. J Infect Dis 165, 1056-1063 (1992).

- Blomster-Hautamaa, D. A., Kreiswirth, B. N., Kornblum, J. S., Novick, R. P. & Schlievert, P. M. The nucleotide and partial amino acid sequence of toxic shock syndrome toxin-1. J Biol Chem 261, 15783-15786 (1986).

- Prasad, G. S. et al. Structure of toxic shock syndrome toxin 1. Biochemistry 32, 13761-13766 (1993).

- Acharya, K. R. et al. Structural basis of superantigen action inferred from crystal structure of toxic-shock syndrome toxin-1. Nature 367, 94-97 (1994).

- Mitchell, D. T., Levitt, D. G., Schlievert, P. M. & Ohlendorf, D. H. Structural evidence for the evolution of pyrogenic toxin superantigens. J Mol Evol 51, 520-531 (2000).

- Betley, M. J., Lofdahl, S., Kreiswirth, B. N., Bergdoll, M. S. & Novick, R. P. Staphylococcal enterotoxin A gene is associated with a variable genetic element. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 81, 5179-5183 (1984).

- Bayles, K. W. & Iandolo, J. J. Genetic and molecular analyses of the gene encoding staphylococcal enterotoxin D. J Bacteriol 171, 4799-4806 (1989).

- Lindsay, J. A., Ruzin, A., Ross, H. F., Kurepina, N. & Novick, R. P. The gene for toxic shock toxin is carried by a family of mobile pathogenicity islands in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol 29, 527-543 (1998).

- Yarwood, J. M. et al. Characterization and expression analysis of Staphylococcus aureus pathogenicity island 3. Implications for the evolution of staphylococcal pathogenicity islands. J Biol Chem 277, 13138-13147 (2002).

- Schlievert, P. M. et al. Pyrogenic toxin superantigen site specificity in toxic shock syndrome and food poisoning in animals. Infect Immun 68, 3630-3634 (2000).

- Schlievert, P. M., Case, L. C., Strandberg, K. L., Abrams, B. B. & Leung, D. Y. Superantigen profile of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from patients with steroid-resistant atopic dermatitis. Clin Infect Dis 46, 1562-1567 (2008).

- Schlievert, P. M. & Peterson, M. L. Glycerol monolaurate antibacterial activity in broth and biofilm cultures. PLoS One 7, e40350 (2012).

- Schlievert, P. M. & Kelly, J. A. Clindamycin-induced suppression of toxic-shock syndrome–associated exotoxin production. J Infect Dis 149, 471 (1984).

- Blomster-Hautamaa, D. A., Kreiswirth, B. N., Novick, R. P. & Schlievert, P. M. Resolution of highly purified toxic-shock syndrome toxin 1 into two distinct proteins by isoelectric focusing. Biochemistry 25, 54-59 (1986).

- Blomster-Hautamaa, D. A. & Schlievert, P. M. Preparation of toxic shock syndrome toxin-1. Methods Enzymol 165, 37-43 (1988).

- Dohlsten, M. et al. Immunotherapy of human colon cancer by antibody-targeted superantigens. Cancer Immunol Immunother 41, 162-168 (1995).

- Salgado-Pabón, W. & Schlievert, P. M. Models matter: the search for an effective Staphylococcus aureus vaccine. Nat Rev Microbiol 12, 585-591 (2014).

- Jett, M., Brinkley, W., Neill, R., Gemski, P. & Hunt, R. Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin B challenge of monkeys: correlation of plasma levels of arachidonic acid cascade products with occurrence of illness. Infect Immun 58, 3494-3499 (1990).

- John, C. C. et al. Staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome erythroderma is associated with superantigenicity and hypersensitivity. Clin Infect Dis 49, 1893-1896 (2009).

- Peterson, M. L. et al. The innate immune system is activated by stimulation of vaginal epithelial cells with Staphylococcus aureus and toxic shock syndrome toxin 1. Infect Immun 73, 2164-2174 (2005).

- Schlievert, P. M. et al. Staphylococcal superantigens stimulate epithelial cells through CD40 to produce chemokines. MBio 10, e00214-19 (2019).

- Schlievert, P. M., Gourronc, F. A., Leung, D. Y. M. & Klingelhutz, A. J. Human keratinocyte response to superantigens. mSphere 5, e00803-20 (2020).

- Moran, M. C., Brewer, M. G., Schlievert, P. M. & Beck, L. A. S. aureus virulence factors decrease epithelial barrier function and increase susceptibility to viral infection. Microbiol Spectr 11, e0168423 (2023).

- Banke, E. et al. Superantigen activates the gp130 receptor on adipocytes resulting in altered adipocyte metabolism. Metabolism: clinical and experimental 63, 831-40 (2014).

- Vu, B. G. et al. Chronic superantigen exposure induces systemic inflammation, elevated bloodstream endotoxin, and abnormal glucose tolerance in rabbits: possible role in diabetes. MBio 6, e02554 (2015).

- Vu, B. G., Gourronc, F. A., Bernlohr, D. A., Schlievert, P. M. & Klingelhutz, A. J. Staphylococcal superantigens stimulate immortalized human adipocytes to produce chemokines. PLoS One 8, e77988 (2013).

- Schlievert, P. M., Bettin, K. M. & Watson, D. W. Inhibition of ribonucleic acid synthesis by group A streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin. Infect Immun 27, 542-548 (1980).

- Dinges, M. M. & Schlievert, P. M. Comparative analysis of lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor alpha activity in serum and lethality in mice and rabbits pretreated with the staphylococcal superantigen toxic shock syndrome toxin 1. Infect Immun 69, 7169-7172 (2001).

- Shands, K. N. et al. Toxic-shock syndrome in menstruating women: association with tampon use and Staphylococcus aureus and clinical features in 52 cases. N Engl J Med 303, 1436-1442 (1980).

- Davis, J. P., Chesney, P. J., Wand, P. J. & LaVenture, M. Toxic-shock syndrome: epidemiologic features, recurrence, risk factors, and prevention. N Engl J Med 303, 1429-1435 (1980).

- Reingold, A. L., Dan, B. B., Shands, K. N. & Broome, C. V. Toxic-shock syndrome not associated with menstruation. A review of 54 cases. Lancet 1, 1-4 (1982).

- Parsonnet, J. Case definition of staphylococcal TSS: a proposed revision incorporating laboratory findings. international Congress and Symposium Series 229, 15 (1998).

- Davis, J. P. et al. Tri-state toxic-shock syndrome study. II. Clinical and laboratory findings. J Infect Dis 145, 441-448 (1982).

- Osterholm, M. T. et al. Tri-state toxic-state syndrome study. I. Epidemiologic findings. J Infect Dis 145, 431-440 (1982).

- Schlievert, P. M. & Blomster, D. A. Production of staphylococcal pyrogenic exotoxin type C: influence of physical and chemical factors. J Infect Dis 147, 236-242 (1983).

- Hill, D. R. et al. In vivo assessment of human vaginal oxygen and carbon dioxide levels during and post menses. J Appl Physiol (1985) 99, 1582-1591 (2005).

- Yarwood, J. M., McCormick, J. K. & Schlievert, P. M. Identification of a novel two-component regulatory system that acts in global regulation of virulence factors of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 183, 1113-1123 (2001).

- Yarwood, J. M. & Schlievert, P. M. Oxygen and carbon dioxide regulation of toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 production by Staphylococcus aureus MN8. J Clin Microbiol 38, 1797-1803 (2000).

- Schlievert, P. M. et al. Vaginal Staphylococcus aureus superantigen profile shift from 1980 and 1981 to 2003, 2004, and 2005. J Clin Microbiol 45, 2704-2707 (2007).

- Schlievert, P. M., Tripp, T. J. & Peterson, M. L. Reemergence of staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome in Minneapolis-St. Paul, Minnesota, during the 2000-2003 surveillance period. J Clin Microbiol 42, 2875-2876 (2004).

- Vergeront, J. M. et al. Prevalence of serum antibody to staphylococcal enterotoxin F among Wisconsin residents: implications for toxic-shock syndrome. J Infect Dis 148, 692-698 (1983).

- Kansal, R. et al. Structural and functional properties of antibodies to the superantigen TSST-1 and their relationship to menstrual toxic shock syndrome. J Clin Immunol 27, 327-338 (2007).

- Parsonnet, J. et al. Prevalence of toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 (TSST-1)-producing strains of Staphylococcus aureus and antibody to TSST-1 among healthy Japanese women. J Clin Microbiol 46, 2731-2738 (2008).

- Parsonnet, J. et al. Prevalence of toxic shock syndrome toxin 1-producing Staphylococcus aureus and the presence of antibodies to this superantigen in menstruating women. J Clin Microbiol 43, 4628-4634 (2005).

- Nonfoux, L. et al. Impact of currently marketed tampons and menstrual cups on Staphylococcus aureus growth and TSST-1 production in vitro. Appl Environ Microbiol (2018).

- Schlievert, P. M. Effect of non-absorbent intravaginal menstrual/contraceptive products on Staphylococcus aureus and production of the superantigen TSST-1. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 39, 31-38 (2020).

- Altemeier, W. A. et al. Staphylococcus aureus associated with toxic shock syndrome: phage typing and toxin capability testing. Ann Intern Med 96, 978-982 (1982).

- Altemeier, W. A., Lewis, S. A., Bjornson, H. S., Staneck, J. L. & Schlievert, P. M. Staphylococcus in toxic shock syndrome and other surgical infections. Development of new bacteriophages. Arch Surg 118, 281-284 (1983).

- Altemeier, W. A., Lewis, S., Schlievert, P. M. & Bjornson, H. S. Studies of the staphylococcal causation of toxic shock syndrome. Surg Gynecol Obstet 153, 481-485 (1981).

- Mueller, E. A., Merriman, J. A. & Schlievert, P. M. Toxic shock syndrome toxin-1, not alpha-toxin, mediated Bundaberg fatalities. Microbiology 161, 2361-2368 (2015).

- Tenover, F. C. et al. Comparison of typing results obtained for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates with the DiversiLab system and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol 47, 2452-2457 (2009).

- Fey, P. D. et al. Comparative molecular analysis of community- or hospital-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47, 196-203 (2003).

- Pragman, A. A., Yarwood, J. M., Tripp, T. J. & Schlievert, P. M. Characterization of virulence factor regulation by SrrAB, a two-component system in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 186, 2430-2438 (2004).

- Spaulding, A. R. et al. Comparison of Staphylococcus aureus strains for ability to cause infective endocarditis and lethal sepsis in rabbits. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2, 18 (2012).

- Salgado-Pabón, W. et al. Superantigens are critical for Staphylococcus aureus infective endocarditis, sepsis, and acute kidney injury. MBio 4, e00494-00413 (2013).

- Spaulding, A. R. et al. Vaccination against Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. J Infect Dis 209, 1955-1962 (2014).

- Spaulding, A. R. et al. Immunity to Staphylococcus aureus secreted proteins protects rabbits from serious illnesses. Vaccine 30, 5099-5109 (2012).

- Schwameis, M. et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of a recombinant toxic shock syndrome toxin (rTSST)-1 variant vaccine: a randomised, double-blind, adjuvant-controlled, dose escalation first-in-man trial. Lancet Infect Dis 16, 1036-1044 (2016).

- Murray, D. L. et al. Localization of biologically important regions on toxic shock syndrome toxin 1. Infect Immun 64, 371-374 (1996).

- Murray, D. L. et al. Immunobiologic and biochemical properties of mutants of toxic shock syndrome toxin-1. J Immunol 152, 87-95 (1994).

- Schlievert, P. M. Staphylococcal enterotoxin B and C mutants and vaccine toxoids. Microbiology Spectrum 11, e04446-04422 (2023).

- Simpson, E. L. et al. Rapid reduction in Staphylococcus aureus in atopic dermatitis subjects following dupilumab treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol 152, 1179-1195 (2023).

- Leung, D. Y. New opportunities, new products. J Allergy Clin Immunol 106, 1043-1044 (2000).

- Leung, D. Y. Atopic dermatitis: new insights and opportunities for therapeutic intervention. J Allergy Clin Immunol 105, 860-876 (2000).

- Irvine, A. D., McLean, W. H. & Leung, D. Y. Filaggrin mutations associated with skin and allergic diseases. N Engl J Med 365, 1315-1327 (2011).

- Davis, C. C., Kremer, M. J., Schlievert, P. M. & Squier, C. A. Penetration of toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 across porcine vaginal mucosa ex vivo: permeability characteristics, toxin distribution, and tissue damage. Am J Obstet Gynecol 189, 1785-1791 (2003).

- Schlievert, P. M. et al. Staphylococcal TSST-1 association with eczema herpeticum in humans. mSphere 6, e0060821 (2021).

- Woods, B. et al. Skin levels of toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 predict the severity of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Jun 16:S0091-6749(25)00612-8 (2025).

- Fischer, A. J. et al. High prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin gene cluster superantigens in cystic fibrosis clinical isolates. Genes (Basel) 10, 1036 (2019).

- Messingham, K. N. et al. TSST-1(+) Staphylococcus aureus in bullous pemphigoid. J Invest Dermatol 142, 1032-1039 (2022).

- Schwab, J. H., Brown, R. R., Anderle, S. K. & Schlievert, P. M. Superantigen can reactivate bacterial cell wall-induced arthritis. J Immunol 150, 4151-4159 (1993).

- Leung, D. Y. et al. Evidence for a streptococcal superantigen-driven process in acute guttate psoriasis. J Clin Invest 96, 2106-2112 (1995).

- Schiffenbauer, J., Johnson, H. M., Butfiloski, E. J., Wegrzyn, L. & Soos, J. M. Staphylococcal enterotoxins can reactivate experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90, 8543-8546 (1993).

- Kotler, D. P., Sandkovsky, U., Schlievert, P. M. & Sordillo, E. M. Toxic shock-like syndrome associated with staphylococcal enterocolitis in an HIV-infected man. Clin Infect Dis 44, e121-123 (2007).

- Lin, Z., Kotler, D. P., Schlievert, P. M. & Sordillo, E. M. Staphylococcal enterocolitis: forgotten but not gone? Dig Dis Sci 55, 1200-1207 (2010).

- Orwin, P. M. et al. Characterization of a novel staphylococcal enterotoxin-like superantigen, a member of the group V subfamily of pyrogenic toxins. Biochemistry 41, 14033-14040 (2002).

- Orwin, P. M. et al. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin L. Infect Immun 71, 2916-2919 (2003).

- Orwin, P. M., Leung, D. Y., Donahue, H. L., Novick, R. P. & Schlievert, P. M. Biochemical and biological properties of Staphylococcal enterotoxin K. Infect Immun 69, 360-366 (2001).

- Schlievert, P. M. Use of intravenous immunoglobulin in the treatment of staphylococcal and streptococcal toxic shock syndromes and related illnesses. J Allergy Clin Immunol 108, S107-110 (2001).

- Pomputius, W. F., Kilgore, S. H. & Schlievert, P. M. Probable enterotoxin-associated toxic shock syndrome caused by Staphylococcus epidermidis. BMC pediatrics 23, 108 (2023).

- Salgado-Pabón, W., Case-Cook, L. C. & Schlievert, P. M. Molecular analysis of staphylococcal superantigens. Methods Mol Biol 1085, 169-185 (2014).

- Elasri, M. O. et al. Staphylococcus aureus collagen adhesin contributes to the pathogenesis of osteomyelitis. Bone 30, 275-280 (2002).

- Hultgren, O. H., Stenson, M. & Tarkowski, A. Role of IL-12 in Staphylococcus aureus-triggered arthritis and sepsis. Arthritis research 3, 41-47 (2001).

- Sakiniene, E., Bremell, T. & Tarkowski, A. Addition of corticosteroids to antibiotic treatment ameliorates the course of experimental Staphylococcus aureus arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 39, 1596-1605 (1996).

- Verdrengh, M. & Tarkowski, A. Role of macrophages in Staphylococcus aureus-induced arthritis and sepsis. Arthritis Rheum 43, 2276-2282 (2000).

- Koliada, A. et al. Association between body mass index and Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in an adult Ukrainian population. BMC Microbiol 17, 120 (2017).

- Sikalidis, A. K. & Maykish, A. The gut microbiome and type 2 diabetes mellitus: Discussing a complex relationship. Biomedicines 8 (2020).

- Vu, B. G. et al. Superantigens of Staphylococcus aureus from patients with diabetic foot ulcers. J Infect Dis 210, 1920-1927 (2014).

- Jackow, C. M. et al. Association of erythrodermic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, superantigen-positive Staphylococcus aureus, and oligoclonal T-cell receptor V beta gene expansion. Blood 89, 32-40 (1997).

- Bernstein, J. M. et al. A superantigen hypothesis for the pathogenesis of chronic hyperplastic sinusitis with massive nasal polyposis. Am J Rhinol 17, 321-326 (2003).

- Schiffenbauer, J., Johnson, H. M., Butfiloski, E. J., Wegrzyn, L. & Soos, J. M. Staphylococcal enterotoxins can reactivate experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90, 8543-8546 (1993).

- Kotler, D. P., Sandkovsky, U., Schlievert, P. M. & Sordillo, E. M. Toxic shock-like syndrome associated with staphylococcal enterocolitis in an HIV-infected man. Clin Infect Dis 44, e121-123 (2007).

- Lin, Z., Kotler, D. P., Schlievert, P. M. & Sordillo, E. M. Staphylococcal enterocolitis: forgotten but not gone? Dig Dis Sci 55, 1200-1207 (2010).

- Orwin, P. M. et al. Characterization of a novel staphylococcal enterotoxin-like superantigen, a member of the group V subfamily of pyrogenic toxins. Biochemistry 41, 14033-14040 (2002).

- Orwin, P. M. et al. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin L. Infect Immun 71, 2916-2919 (2003).

- Orwin, P. M., Leung, D. Y., Donahue, H. L., Novick, R. P. & Schlievert, P. M. Biochemical and biological properties of Staphylococcal enterotoxin K. Infect Immun 69, 360-366 (2001).

- Schlievert, P. M. Use of intravenous immunoglobulin in the treatment of staphylococcal and streptococcal toxic shock syndromes and related illnesses. J Allergy Clin Immunol 108, S107-110 (2001).

- Pomputius, W. F., Kilgore, S. H. & Schlievert, P. M. Probable enterotoxin-associated toxic shock syndrome caused by Staphylococcus epidermidis. BMC pediatrics 23, 108 (2023).

- Salgado-Pabón, W., Case-Cook, L. C. & Schlievert, P. M. Molecular analysis of staphylococcal superantigens. Methods Mol Biol 1085, 169-185 (2014).

- Elasri, M. O. et al. Staphylococcus aureus collagen adhesin contributes to the pathogenesis of osteomyelitis. Bone 30, 275-280 (2002).

- Hultgren, O. H., Stenson, M. & Tarkowski, A. Role of IL-12 in Staphylococcus aureus-triggered arthritis and sepsis. Arthritis research 3, 41-47 (2001).

- Sakiniene, E., Bremell, T. & Tarkowski, A. Addition of corticosteroids to antibiotic treatment ameliorates the course of experimental Staphylococcus aureus arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 39, 1596-1605 (1996).

- Verdrengh, M. & Tarkowski, A. Role of macrophages in Staphylococcus aureus-induced arthritis and sepsis. Arthritis Rheum 43, 2276-2282 (2000).

- Koliada, A. et al. Association between body mass index and Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in an adult Ukrainian population. BMC Microbiol 17, 120 (2017).

- Sikalidis, A. K. & Maykish, A. The gut microbiome and type 2 diabetes mellitus: Discussing a complex relationship. Biomedicines 8 (2020).

- Vu, B. G. et al. Superantigens of Staphylococcus aureus from patients with diabetic foot ulcers. J Infect Dis 210, 1920-1927 (2014).

- Jackow, C. M. et al. Association of erythrodermic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, superantigen-positive Staphylococcus aureus, and oligoclonal T-cell receptor V beta gene expansion. Blood 89, 32-40 (1997).

- Bernstein, J. M. et al. A superantigen hypothesis for the pathogenesis of chronic hyperplastic sinusitis with massive nasal polyposis. Am J Rhinol 17, 321-326 (2003).