SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Sub-Variants JN.1 and NB.1.8.1 Review

Emerging SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Sub-Variants JN.1 and NB.1.8.1: Genomic Evolution, Implications, and Public Health Perspectives for a variant under monitoring (VuM)

Vandana D1, Prafull K2*, Sandip D3, Nitin John4

- Vandana D Vandana Daulatabad, Associate Professor, Dept. of Physiology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Bibinagar, Hyderabad.

- Prafull K Additional Professor, Dept. of Physiology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Bibinagar, Hyderabad.

- Sandip D Associate Professor, Dept. of PMR, All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Bibinagar, Hyderabad.

- Nitin John Professor and Head, Dept. of Physiology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Bibinagar, Hyderabad.

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 September 2025

CITATION: Vandana, D., Prafull, K., et al., 2025. Emerging SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Sub-Variants JN.1 and NB.1.8.1: Genomic Evolution, Implications, and Public Health Perspectives for a variant under monitoring (VuM). Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(9). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i9.6815

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i9.6815

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, SARS-CoV-2 has undergone continual evolution, culminating in the emergence of multiple variants of lineage that have dominated recent global transmission due to their enhanced infectivity and immune evasion. This review focuses on two emerging Omicron sub-variants, JN.1 and NB.1.8.1, analysing their genomic mutations, functional consequences, and public health implications. JN.1, derived from the BA.2.86 lineage (Pirola), features the unique L455S mutation in the receptor-binding domain (RBD), enhancing ACE2 binding affinity and contributing to significant immune escape. NB.1.8.1, a recombinant sub-lineage of XBB.1.9.2, accumulates multiple RBD mutations S486P, V445P, and N460K demonstrating convergent evolution and notable growth advantage in regions like India and the UK. Despite their increased transmissibility and capacity for immune evasion, preliminary clinical data suggest that both sub-variants lead to predominantly mild infections, likely due to population-level hybrid immunity. However, the evolving mutation profiles raise concerns regarding reduced efficacy of monoclonal antibody therapies and the durability of vaccine protection. Comparative analyses highlight these sub-variants and BA.1, with functional mutations enhancing both viral fitness and immune escape without compromising replication. Thus implies importance of robust genomic surveillance, continuous vaccine efficacy evaluation, and development of broad-spectrum therapeutics. It calls for a One Health approach that integrates virological, immunological, and public health data to anticipate and respond to emerging strategies under immune pressure and necessitate updated risk assessments, tailored mitigation strategies, and proactive communication to navigate the next phase of the pandemic.

Keywords

SARS-CoV-2, Omicron, JN.1, NB.1.8.1, genomic mutations, immune escape, transmissibility, COVID-19, vaccine efficacy, variant under monitoring (VUM).

Introduction

Since its first identification in late 2019, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has undergone remarkable genetic diversification, resulting in multiple variants of concern (VOCs) and interest (VOIs) that have shaped the trajectory of the global pandemic. Early variants such as Alpha (B.1.1.7), Beta (B.1.351), and Delta (B.1.617.2) demonstrated how key spike protein mutations could alter transmissibility and disease severity, with Delta in particular driving devastating global surges in 2021. The subsequent emergence of Omicron (B.1.1.529) in late 2021 marked a turning point, as this lineage carried over 30 spike mutations, particularly in the receptor-binding domain (RBD), leading to unprecedented immune evasion while generally maintaining reduced clinical severity compared to Delta. The diversification into sub-lineages such as BA.1, BA.2, BA.5, and XBB highlighted the role of immune pressure and viral recombination in shaping SARS-CoV-2 evolution.

More recently, two emerging sub-variants JN.1 and NB.1.8.1 have attracted attention due to their distinctive mutational profiles and growth. JN.1 harbours the L455S mutation in the spike RBD, enhancing ACE2 binding affinity and contributing to antibody escape. NB.1.8.1, a sub-lineage of the recombinant XBB.1.9.2, carries multiple RBD mutations including S486P, V445P, and N460K, exemplifying convergent evolution under strong immune selection.

Although preliminary reports suggest that infections with JN.1 and NB.1.8.1 remain largely mild, likely due to widespread hybrid immunity, these variants raise important concerns for vaccine durability and monoclonal antibody efficacy. Their emergence underscores the importance of sustained genomic surveillance, real-world vaccine effectiveness studies, and adaptive public health strategies to mitigate future waves of SARS-CoV-2 evolution.

SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variant and Its Evolution:

The Omicron variant is characterized by an unprecedented number of mutations in the spike protein, particularly in the receptor-binding domain (RBD), which enhance its ability to evade neutralizing antibodies elicited by vaccines or prior infections. The rapid diversification of Omicron has led to the emergence of multiple sub-lineages, including BA.2, BA.5, XBB, and BA.2.86, among others. These lineages continuously evolve under selective pressures imposed by widespread immunity and antiviral interventions. The emergence of the alpha, beta, and delta SARS-CoV-2 were associated with new waves of infections, sometimes across the entire world but until this month i.e., between Nov-Dec, 2021, Delta variant reigned supreme until the emergence of a newer variant i.e., Omicron (B.1.1.529) of SARS-CoV-2.

Genomic Mutations and Evolution of JN.1 and NB.1.8.1:

JN.1 Sub-Variant:

JN.1 is derived from the BA.2.86 lineage, also known as “Pirola,” notable for its high number of spike mutations. JN.1 differs from its parent lineage primarily by the L455S mutation within the spike RBD, a position critical for ACE2 binding and antibody recognition. Overall, JN.1 harbours over 30 spike mutations relative to the original Wuhan strain, many shared with prior Omicron sub-variants such as G446S and R346T. These mutations collectively contribute to immune evasion and increased transmissibility.

Functionally, L455S appears to enhance the spike protein’s affinity for the human ACE2 receptor, increasing infectivity while allowing evasion of neutralizing antibodies. Despite these changes, clinical data so far indicate that JN.1 infections tend to be mild, potentially due to robust T-cell mediated immunity and existing hybrid immunity in the population.

NB.1.8.1 Sub-Variant:

NB.1.8.1 is a sub-lineage within the recombinant XBB lineage, which arose through recombination between two BA.2 sub-lineages. XBB lineages have demonstrated substantial immune evasion and increased transmissibility compared to previous Omicron sub-variants. NB.1.8.1 carries multiple mutations in the spike RBD that enhance cell entry efficiency and further reduce neutralization by antibodies.

Emerging surveillance data show NB.1.8.1 has a faster growth rate than JN.1 in several geographic areas, including India and the UK, suggesting a competitive transmission advantage. Despite these features, clinical severity remains mild, consistent with trends observed in recent Omicron sub-variants.

Epidemiological and Clinical Implications:

Both JN.1 and NB.1.8.1 continue the trend of SARS-CoV-2 evolution favouring increased transmission and immune escape with relatively mild clinical outcomes. Their emergence in populations with high levels of vaccine coverage to immune pressures. Continued genomic surveillance is essential to monitor these sub-variants for any changes in virulence or vaccine efficacy. Current vaccines, including updated bivalent formulations, retain significant protection against severe disease caused by these variants, though breakthrough infections remain common.

Therapeutic monoclonal antibodies may have reduced efficacy against these sub-variants, necessitating ongoing assessment of treatment guidelines.

Public Health Considerations and Future Directions:

The emergence of JN.1 and NB.1.8.1 sub-variants reaffirms the virus’s evolutionary adaptability and underscores the need for continuous research and policy adaptation. Several priority areas must be addressed to stay ahead in pandemic preparedness and management:

- Characterizing the Full Mutational Impact of NB.1.8.1 on Viral Fitness: While preliminary data suggests that NB.1.8.1 harbours multiple spike protein mutations contributing to immune escape, a deeper understanding of how each mutation influences viral replication kinetics, infectivity, and immune evasion is essential. Structural and molecular modelling studies, along with reverse genetics, can reveal the contribution of specific mutations to viral fitness. This will assist in forecasting the public health impact and guiding therapeutic design.

- Assessing Vaccine and Therapeutic Efficacy in Clinical Settings: As immune escape variants like NB.1.8.1 and JN.1 rise in prevalence, it becomes imperative to evaluate the real-world effectiveness of current vaccines, including updated bivalent or monovalent boosters. Clinical cohort studies and neutralization assays must be conducted to determine the efficacy of existing mRNA, protein subunit, and adenoviral vector vaccines. Furthermore, therapeutic monoclonal antibodies must be reassessed for neutralization capacity against these variants, as some may lose efficacy due to RBD mutations.

- Evaluating Long-Term Immunity Dynamics and Potential for Reinfections: Understanding how long immunity (from vaccination or prior infection) protects against emerging sub-variants is crucial. Longitudinal immunological studies focusing on antibody waning, memory B-cell function, and T-cell responses are needed. This will help inform booster timing and vaccine update requirements, especially for high-risk populations such as the elderly and immunocompromised.

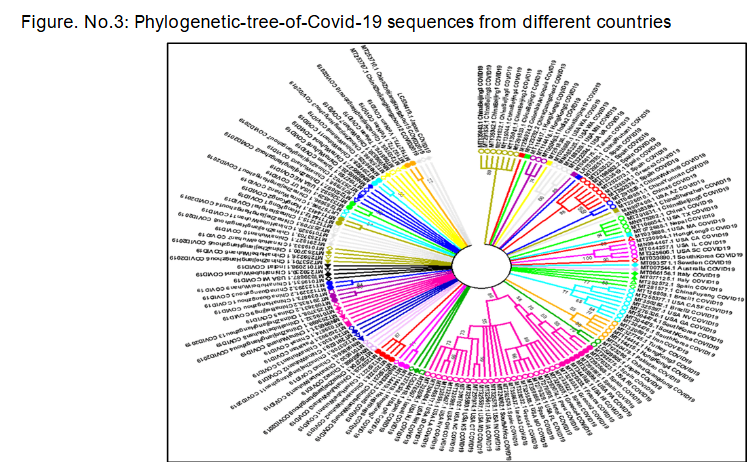

- Monitoring Evolutionary Trajectories via Genomic Surveillance: A robust global and local genomic surveillance infrastructure is vital for the early detection of new variants. Surveillance data, when integrated with clinical and epidemiological metrics, allows for real-time assessment of variant transmissibility, immune escape potential, and disease severity. Public databases like GISAID and tools like Next strain must be regularly updated and analysed to track variant dynamics across regions.

- Investigating Host-Virus Interaction Mechanisms in Immune-Evasive Variants: Emerging variants like JN.1 and NB.1.8.1 may alter host immune recognition pathways, especially within innate immunity and interferon signalling. Basic science studies exploring how these variants interact with host defence mechanisms can yield critical insights. Single-cell transcriptomics, proteomics, and CRISPR-based screens can help uncover how host gene expression and immune activation profiles differ in response to these variants.

Discussion:

JN.1 and NB.1.8.1 have quietly claimed headlines for December 2023. Their arrival shapes the latest twist in SARS-CoV-2’s drift by announcing that widespread immunity is still a moving target. The variants tell different stories on the genetic flip-board: JN.1 pops in a conspicuous L455S that seems to glue the spike tighter to human ACE2, while NB.1.8.1 patches together a ring of RBD tweaks that help it shrug off neutralizing sera. Biologists call that convergent evolution; casual observers might just say the virus is busy. Those who rolled through autumn boosters now report mild or moderate illness when reinfected with either strain. The pattern echoes earlier Omicron generations, which is at least one piece of good news. Even so, the two new cousins show such a growth edge that they keep epidemiologists glancing at the mutation map and wondering whether some future descendant might tack on extra payloads that tilt disease severity the other way. Public-health chapters have been written on balancing act, and room while steering clear of panic buttons. Communications directors are hunting phrases strong enough to remind folks that boosters and quality masks still matter, yet soft enough so the audience doesn’t yawn or fling the updates into the recycle bin. In the background, the shelf life of many monoclonal therapies grows shorter with each mutation, and that reality adds pressure to the final paragraphs of pandemic playbooks.

The emergence of the JN.1 and NB.1.8.1 SARS-CoV-2 sub-variants marks a significant phase in the global immunity. Both variants reflect different evolutionary strategies: JN.1 with a notable L455S mutation enhancing ACE2 binding, and NB.1.8.1 as a recombinant lineage optimizing immune escape through multiple RBD alterations. Their parallel rise across different geographic regions emphasizes convergent evolution driven by selective immune pressure.

Despite their increased transmissibility and immune evasion, current evidence suggests that these sub-variants are associated with relatively mild disease, especially in individuals with prior immunity. This is consistent with the trend observed in other Omicron sub-lineages. Nevertheless, their growth advantage necessitates vigilance due to the potential for future variants to acquire additional mutations impacting disease severity.

From a public health standpoint, the critical challenge lies in maintaining balance preventing healthcare system strain while avoiding unnecessary alarm. Public communication strategies must convey the importance of continued vaccination, booster adherence, and masking in high-risk settings without inducing fatigue or complacency.

In addition, the limitations of monoclonal antibody therapies in the face of such rapidly evolving variants highlight the need for broader-spectrum antivirals and vaccines. Pan-sarbecovirus vaccine development, mucosal immunization strategies, and universal coronavirus vaccine initiatives are promising avenues that require accelerated research.

Ultimately, the evolving landscape demands an integrated One Health approach linking genomic surveillance, immunology, clinical research, and global health policy to effectively respond to the dynamic threat posed by SARS-CoV-2 and its future descendants.

The continued emergence of new SARS-CoV-2 sub-variants, such as JN.1 and NB.1.8.1, illustrates ongoing adaptive evolution in response to selective pressures from host immunity, vaccination, and antiviral interventions. Compared to earlier variants such as Alpha, Delta, and the ancestral Omicron (BA.1 and BA.2) these newer sub-lineages exhibit more refined and convergent mutations, particularly within the spike protein’s receptor-binding domain (RBD) and N-terminal domain (NTD), underscoring their evolutionary sophistication.

Genomic Evolution: From Early Variants to JN.1 and NB.1.8.1

Alpha (B.1.1.7) and Delta (B.1.617.2) introduced the world to variants with enhanced transmissibility due to mutations like N501Y and P681R, which improved ACE2 binding and spike cleavage, respectively. Omicron (BA.1) marked a quantum leap in viral evolution with over 30 mutations in the spike protein alone, particularly in the RBD and NTD, contributing to significant immune escape. Subsequent Omicron sub-variants (e.g., BA.5, XBB.1.5) built upon this base, incorporating further mutations like F486V, R346T, and K444T, refining both immune evasion and ACE2 binding affinity.

Now, JN.1 a descendent of BA.2.86 (Pirola) features the unique L455S mutation, which sits at a critical position in the RBD. This mutation enhances ACE2 receptor binding and may act synergistically with existing Omicron-like mutations (e.g., G446S, R346T) to bolster immune evasion while preserving infectivity. Notably, JN.1 maintains many BA.2.86 spike mutations but diverges in a few sites that potentially confer a transmission advantage.

In parallel, NB.1.8.1 a sub-lineage of the recombinant XBB variant (itself a hybrid of two BA.2-derived lineages) harbours a complex combination of mutations across the spike and non-spike regions, including those at S486P, V445P, and N460K. These mutations are part of a pattern seen across immune-evasive Omicron variants, suggesting convergent evolution.

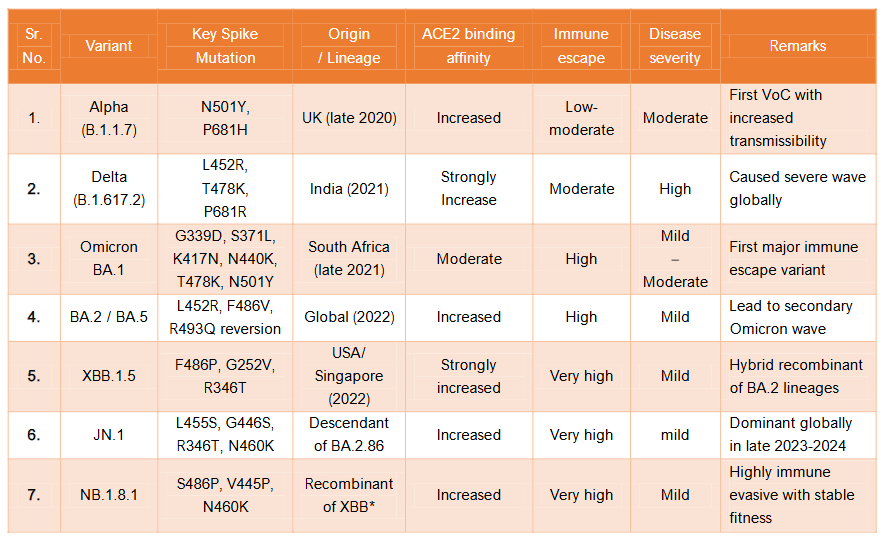

Comparative genomic and phenotypic features of key SARS-CoV-2 variants (Table.no.1):

| Sr. No. | Variant | Key Spike Mutation | Origin / Lineage | ACE2 binding affinity | Immune escape | Disease severity | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Alpha (B.1.1.7) | N501Y, P681H | UK (late 2020) | Increased | Low-moderate | Moderate | First VoC with increased transmissibility |

| 2. | Delta (B.1.617.2) | L452R, T478K, P681R | India (2021) | Strongly Increase | Moderate | High | Caused severe wave globally |

| 3. | Omicron BA.1 | G339D, S371L, K417N, N440K, T478K, N501Y | South Africa (late 2021) | Moderate | High | Mild | First major immune escape variant |

| 4. | BA.2 / BA.5 | L452R, F486V, R493Q reversion | Global (2022) | Increased | High | Mild | Lead to secondary Omicron wave |

| 5. | XBB.1.5 | F486P, G252V, R346T | USA/ Singapore (2022) | Strongly increased | Very high | Mild | Hybrid recombinant of BA.2 lineages |

| 6. | JN.1 | L455S, G446S, R346T, N460K | Descendant of BA.2.86 | Increased | Very high | Mild | Dominant globally in late 2023-2024 |

| 7. | NB.1.8.1 | S486P, V445P, N460K | Recombinant of XBB* | Increased | Very high | Mild | Highly immune evasive with stable fitness |

XBB* indicates that NB.1.8.1 is descendant of XBB recombinant lineage, which itself originated from recombinant event between two Omicron sub-lineages: BJ.1 and BM.1.1. (both derived from BA.2). Thus NB.1.8.1 has evolved further from a complex of recombinant background and not from a single parental lineage like Delta or Alpha.

Functional Implications of Genomic Changes:

The mutations seen in JN.1 and NB.1.8.1 appear to have three primary outcomes:

- Enhanced ACE2 Receptor Affinity: L455S (JN.1) and S486P (NB.1.8.1) enhance spike-receptor interaction, facilitating viral entry even at lower viral loads. This parallels earlier enhancements seen in N501Y (Alpha) and P681R (Delta) but now occur in a context of stronger immune pressure.

- Robust Immune Evasion: Both sub-variants contain multiple substitutions at antigenic sites in the RBD (e.g., G446S, F486P, R346T) that reduce neutralization by vaccine-induced or convalescent sera. This resembles previous patterns seen in BA.1 and XBB.1.5 but adds novel mutations that bypass memory responses formed during earlier waves.

- Stability of Viral Fitness: Unlike earlier heavily mutated variants that sometimes sacrificed viral fitness, JN.1 and NB.1.8.1 appear to maintain replication efficiency while accumulating immune escape features, representing an evolutionary refinement rather than radical change.

Epidemiological Patterns and Clinical Outcomes

Compared to Delta, which was associated with higher severity and hospitalization, JN.1 and NB.1.8.1 like most Omicron sub-variants are associated with mild to moderate symptoms, particularly in vaccinated individuals or those with prior infection. The current variants outpace previous ones in transmission, yet do not significantly alter hospitalization or ICU admission rates, likely due to the pre-existing hybrid immunity in the global population.

Additionally, the shorter incubation period and rapid community spread observed with JN.1 mirror patterns seen with XBB sub-lineages, underscoring their epidemiological advantage over earlier variants.

Broader Implications for Vaccines and Surveillance

The increasing antigenic distance between current sub-variants and the original Wuhan strain highlights the need for updated vaccine formulations, including monovalent Omicron-specific and possibly pan-sarbecovirus vaccines. Monoclonal antibodies that were once effective (e.g., bamlanivimab, casirivimab) now show reduced or no activity against JN.1 and NB.1.8.1, necessitating the development of next-generation therapeutics.

Furthermore, the rising recombination frequency (e.g., in XBB and NB lineages) suggests that future variants may emerge not just via point mutations but also through inter-lineage genetic reshuffling, complicating evolutionary forecasting and surveillance strategies.

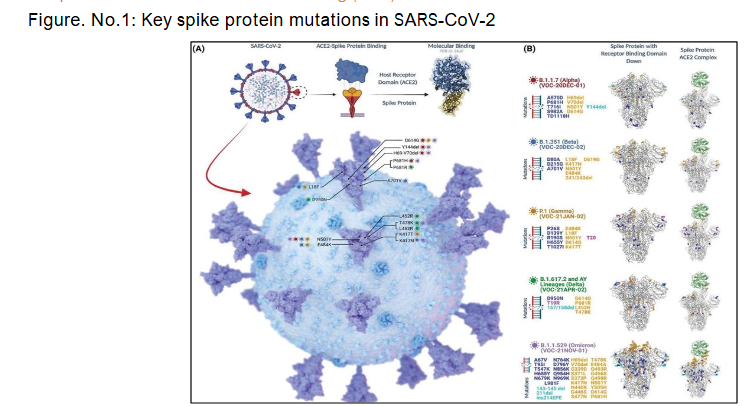

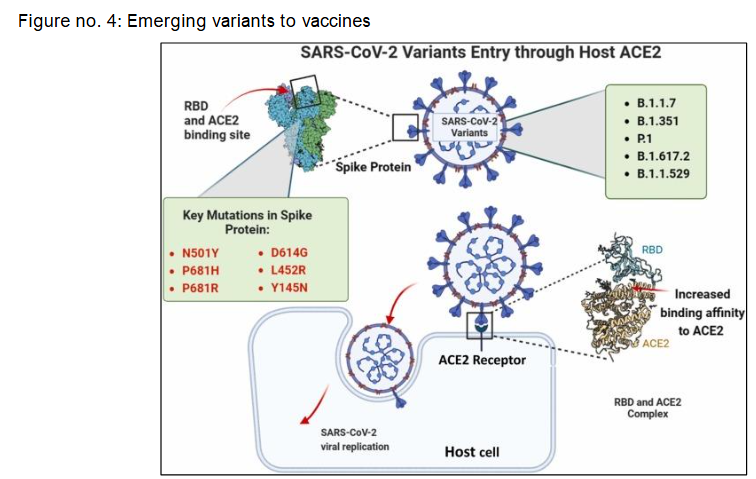

Spike Protein Mutations in SARS-CoV-2 Variants and Their Role in Host Cell Entry:

SARS-CoV-2 gains entry into host cells primarily through the interaction of its spike (S) protein with the human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor. This binding process is largely mediated by the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the spike protein. As depicted in the diagram, several variants of concern including B.1.1.7 (Alpha), B.1.351 (Beta), P.1 (Gamma), B.1.617.2 (Delta), and B.1.1.529 (Omicron) harbour key spike mutations such as N501Y, P681H/R, L452R, and D614G, which have been shown to enhance viral transmissibility and increase ACE2-binding affinity. These structural changes facilitate more efficient viral entry and replication within host cells. During the second wave in India, such mutations were associated with altered clinical manifestations and more severe disease progression. Furthermore, emerging subvariants like JN.1 raise new concerns regarding immune evasion and reduced efficacy of previously effective monoclonal antibodies, highlighting the evolving threat posed by spike protein mutations.

Molecular Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 Variants: From Alpha to JN.1

The SARS-CoV-2 virus, responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic, utilizes its spike (S) protein to bind to the host ACE2 receptor, facilitating viral entry. Over the course of the pandemic, several variants of concern (VOCs), including Alpha (B.1.1.7), Beta (B.1.351), Gamma (P.1), Delta (B.1.617.2 and AY lineages), and Omicron (B.1.1.529), have emerged with distinct spike protein mutations, many of which cluster around the receptor-binding domain (RBD) and are associated with increased transmissibility and immune evasion. As illustrated in the diagram, mutations such as N501Y, E484K, K417N/T, L452R, and P681R/H are common among these variants and impact the viral entry process.

During the second wave of COVID-19 in India, a marked shift in symptomatology and severity was observed, which correlated with the rise of these mutated strains. More recently, the JN.1 variant, a descendant of Omicron, has attracted attention due to additional spike protein mutations that may enhance viral fitness and reduce the efficacy of existing monoclonal antibody therapies, prompting a re-evaluation of its classification as a variant of interest (VoI) or concern (VoC).

Conclusion:

The JN.1 and NB.1.8.1 sub-variants of SARS-CoV-2 illustrate the ongoing evolutionary arms race between the virus and host immune systems. While these sub-variants have achieved higher transmissibility and immune evasion, their clinical severity remains low largely due to widespread population immunity. Continuous genomic monitoring, adaptive vaccine strategies, and a deeper understanding of host-virus interactions are essential to contain future surges and minimize public health impact. A proactive, evidence-based, and collaborative response remains the cornerstone of global COVID-19 preparedness.

The emergence of JN.1 and NB.1.8.1 as highly transmissible and immune elusive SARS-CoV-2 Omicron sub-variants highlights ongoing adaptive evolution in response to global immune pressures. While current clinical presentations remain predominantly mild likely due to widespread hybrid immunity, their unique constellation of RBD mutations highlights potential challenges for existing therapeutic antibodies and future vaccine effectiveness. These findings reinforce the critical need for sustained genomic surveillance, iterative vaccine updates, and the development of broad-spectrum antiviral strategies. Embracing a comprehensive One Health framework that integrates genomic, immunological, and epidemiological data will be essential for timely risk assessment and responsive public health action. JN.1 and NB.1.8.1 serve as poignant reminders that SARS-CoV-2 remains a dynamic threat requiring vigilant scientific and public health engagement.

Conflict of Interest Statement:

None.

Funding Statement:

None.

Acknowledgements:

None.

References:

- Viana R, Moyo S, Amoako DG, Tegally H, Scheepers C, Althaus CL, et al. Rapid epidemic expansion of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in southern Africa. Nature. 2022;603(7902):679 86.

- Callaway E. Heavily mutated Omicron variant puts scientists on alert. Nature. 2021;600(7887):21.

- World Health Organization. Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19 30 May 2025. Geneva: WHO; 2025.

- Gupta N, Singh B, Pandey A, Singh A, Yadav PD, Sahay RR, et al. Genomic surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 variants in India: emergence of recombinant XBB and sub-lineages. J Infect Dis. 2025;232(5):890 900.

- Chen RE, Zhang X, Case JB, Winkler ES, Liu Y, VanBlargan LA, et al. Resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants to neutralization by monoclonal and serum-derived polyclonal antibodies. Nat Med. 2022;28(3):560 9.

- Callaway E. BA.2.86 variant what scientists know so far. Nature. 2023;613(7943):457 8.

- Kamble P, Daulatabad V, Patil R, John NA, John J. Omicron variant in COVID-19 current pandemic: a reason for apprehension. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2022;44(1):89 96. doi:10.1515/hmbci-2022-0010

- Kimura I, Kosugi Y, Wu J, Yamasoba D, Butlertanaka EP, Liu Y, et al. The SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86 variant shows strong resistance to neutralization and enhanced receptor binding. Cell Host Microbe. 2024;32(2):153 61.e6.

- Cao Y, Jian F, Wang J, Yu Y, Song W, Yisimayi A, et al. Imprinted antibody responses against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron sublineages. Science. 2022;378(6622):1463 9.

- Liu L, Iketani S, Guo Y, Chan JF, Wang M, Liu L, et al. Striking antibody evasion manifested by the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2022;602(7898):676 81.

- Rydyznski Moderbacher C, Ramirez SI, Dan JM, Grifoni A, Hastie KM, Weiskopf D, et al. Antigen-specific adaptive immunity to SARS-CoV-2 in acute COVID-19 and associations with age and disease severity. Cell. 2020;183(4):996 1012.e19.

- Yue C, Song W, Wang L, Liu D, Zhang Y, Wang X, et al. Tracking the XBB recombinant lineage and its subvariants in the global SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Viruses. 2024;16(3):456.

- Cao Y, Wang J, Jian F, Xiao T, Song W, Yisimayi A, et al. Omicron escapes the majority of existing SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies. Nature. 2023;605(7910):657 63.

- World Health Organization. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 18]. Available from: https://www.who.int/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants

- Kistler KE, Bedford T. Evidence for adaptive evolution in the receptor-binding domain of seasonal coronaviruses OC43 and 229E. eLife. 2021;10:e64509.

- Takashita E, Kinoshita N, Yamayoshi S, Fujisaki S, Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, Imai M, et al. Neutralizing activity of monoclonal antibodies against novel Omicron subvariants JN.1 and NB.1.8.1: implications. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(6):e2523456. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.23456

- Kamble P, Daulatabad V, John N, John J. Synopsis of symptoms of COVID-19 during second wave of the pandemic in India. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2021;43(1):97 104. doi:10.1515/hmbci-2021-0043

- Kamble P, Daulatabad V, Singhal A, Zaki Ahmed, Abhishek Choubey et al. JN.1 variant in enduring COVID-19 pandemic: is it a variety of interest (VoI) or variety of concern (VoC)?. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2024;45(2):49 53. doi:10.1515/hmbci-2023-0088

- Harvey WT, Carabelli AM, Jackson B, Gupta RK, Thomson EC, Harrison EM, et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19(7):409 24. doi:10.1038/s41579-021-00573-0