Sensory-Motor Modulation in Temporomandibular Disorders

Sensory-Motor Modulation in the Masticatory Apparatus and in Temporomandibular Disorders: from Basic Science to Clinical Practice

Nicolas Fougeront, DDS1

- Consultation de troubles fonctionnels oro-faciaux, service de médecine bucco-dentaire/odontologie, groupe hospitalier Pitié-Salpétrière Charles-Foix, 94200 Ivry-sur-Seine, France

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED:31 May 2025

CITATION: Fougeront, N., 2025. Sensory-Motor Modulation in the Masticatory Apparatus and in Temporomandibular Disorders: from Basic Science to Clinical Practice. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(5). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i5.6561

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i5.6561

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

The jaw sensory-motor system is involved in a wide range of functions: respiration, deglutition, mastication/sucking, verbal/non-verbal expression and protective mechanisms (coughing, prevention from aspiration, …). Some of these tasks may be altered/impaired in temporomandibular disorders that may even impair feeding behaviour. It is suggested that motor maladaptation is due to poor sensory-motor control. Indeed, the excitability of trigeminal reflexes may be modified both in experimental and in clinical painful conditions. However, this research field is a conflicting area. Thus, the aim of this narrative review is first to address the trigeminal sensory-motor control in a healthy state in mastication with a special focus on the type of control either feedback or feedforward that are not mutually exclusive but cooperate. Secondly, it is considered whether there is chronic pain-related modulation of trigeminal sensory-motor control in temporomandibular disorders. Some additional data concerning the spinal system in other musculoskeletal disorders are considered. Mostly, proprioceptive feedback control, i.e. stretch reflex and feedforward control are depressed in musculoskeletal disorders. Protective or withdrawal reflex threshold may be decreased. It would favour protective behaviour. This knowledge could be of clinical interest in functional rehabilitation of musculoskeletal disorders such as temporomandibular disorders. It is suggested that a highly regular rhythm of movement repetitions would improve efficiency of feedback and feedforward control and finally muscle co-ordination. A better knowledge of sensory-motor regulation could also help to understand what is referred clinically to “(mal)adaptation” in oral rehabilitation procedures involving some changes in dental occlusion.

Keywords:

temporomandibular joint disorder, musculoskeletal pain, facial pain, chronic pain, motor activity, mastication, deglutition, reflex, feedback control, feedforward control, rehabilitation, dental occlusion.

1. Introduction

Besides tonic “resting” activity, the neck and craniomandibular muscles are involved in a wide range of motor tasks: respiration, deglutition, mastication or sucking, verbal or non-verbal (facial) expressions and protective mechanisms e.g. vomiting, coughing, prevention from aspiration, … Furthermore, mastication, deglutition, and respiration are coordinated during feeding behaviour. Additionally, jaw and cervical motor systems cooperate as it is in jaw-neck co-ordination during chewing and biting, and in jaw and neck muscle co-activation during tooth clenching or grinding, and sleep bruxism. Finally, there is jaw-neck reciprocal motor interaction in painful conditions such as temporomandibular disorder (TMD) and neck pain or whiplash-associated disorder. Thus, TMD-related pain disrupts neck muscle activity, reciprocally neck pain interferes with jaw muscle activity. These complex and interrelated tasks in the neck and craniofacial areas require motor activity to be finely tuned by sensory-motor controls where their efficiency is age-dependent. Some of these motor tasks or behaviours, i.e. mastication, deglutition and even feeding behaviour may be altered and/or impaired in TMD. Thus, it may be questioned whether sensory-motor controls are still efficient in such chronic pain conditions. Reflexes are the “simplest” controls. These are not stereotyped but modulated, i.e. changes in excitability or gain by nociceptive input or pain. Hence spinal and trigeminal reflexes have been investigated both in clinical pain conditions and in experimental pain models e.g. acute tonic joint or muscle pain in animals or humans. This quest might contribute to the understanding of the pathophysiology of musculoskeletal disorders (MSD) such as TMD. However, modulation of trigeminal reflexes in clinical and chronic pain conditions is a conflicting area. These inconsistencies might lie in the standardising weaknesses of some experimental protocols. However, these standards are difficult to meet especially in chronic pain patients. Since then, clinical trials have been conducted with these pitfalls in mind. Thus, this narrative review aims to update and consider whether there is chronic pain-related modulation of trigeminal sensory-motor controls in TMD. If necessary, the TMD data are compared to what is known about other MSD or conditions involving the spinal system. Beforehand, some aspects of trigeminal sensory-motor controls in healthy state are reviewed in focussing on the type of motor control either feedback or feedforward. Finally, the potential clinical implications of this knowledge will be addressed.

1.1 ARTICLE SEARCHING-STRATEGY

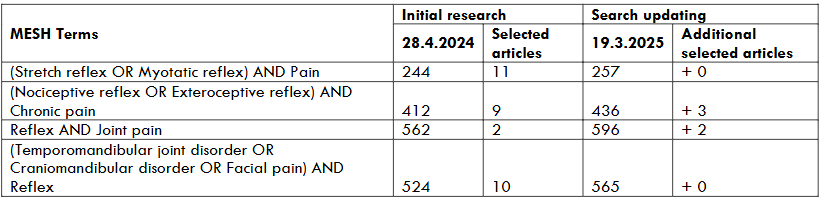

Sensory-motor control in healthy state is addressed in a narrative review (2nd part of the article) and a manual search for articles was carried out. With regard to sensory-motor control in clinical MSD and TMD (3rd part), research in the Pubmed data-base was realised and completed manually if necessary. The initial research (28 April 2024) has been updated (19 March 2025). With regard to orofacial pain conditions and the trigeminal system, particular attention has been paid to the articles published after 1998, due to the first topical review by De Laat et al. in 1998 (“Are jaw reflexes modulated during clinical or experimental orofacial pain?”) followed by a review (“Masseter reflexes modulated by pain.”) of Svensson in 2002. In order to complete the discussion and to compare the data between the trigeminal and the spinal system, a search was made about the other MSD involving the spinal system (Table 1). The included articles are clinical trials or systematic review and meta-analyses with outcome measures evaluating electromyographic activity of the different reflexes (flexor/withdrawal reflex, myotatic/stretch reflex or H-reflex). Cases reports are excluded.

2. PHYSIOLOGY: SENSORY-MOTOR CONTROL IN THE MASTICATORY APPARATUS

2.1 The trigeminal sensory-motor system compared to the spinal system

Based on muscle activity according to gravity, the trigeminal and the spinal sensory-motor systems can be compared. Accounting for their antigravity activity, the jaw-closing muscles and the extensor muscles in the locomotor apparatus are considered to be homologues. The reverse applies to the jaw-opening and locomotor flexor muscles. Similarly, the reflexes of both systems can be compared. One considers the jaw-stretch (jaw-closing) and jaw-opening reflexes as the trigeminal equivalents of the spinal myotatic- and flexion-reflexes, respectively. However, the trigeminal sensory-motor system exhibits some specificities. In humans, it is worth noting that the so-called “jaw-opening” reflex induces jaw-closing α-motoneurons inhibition only but no jaw-opening α-motoneurons activation. Hence Türker suggests calling it “elevator-inhibition reflex”. Furthermore, unlike the spinal system, the reciprocal inhibition principle is partial in the trigeminal system, i.e. it is not symmetrical between agonistic and antagonistic muscles. Indeed, the jaw-closing α-motoneurons only may be hyperpolarised (inhibited) during jaw opening, whereas the jaw-opening α-motoneurons are never hyperpolarised but are silent only during jaw closing. Finally, it is worth noting that there is little evidence on the existence of Golgi tendinous organs in the masticatory muscles, and the inverse stretch reflex has never been investigated in the trigeminal system due to experimental impossibilities. Thus, the “wiring” and the connections of this reflex are only suppositional.

2.2 Motor activity driving mastication and its modulation

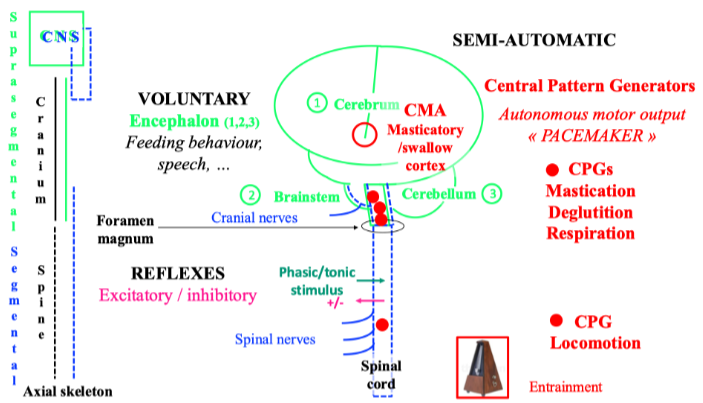

Three types of motor activity drive muscle contraction within the masticatory apparatus: voluntary activity (suprasegmental), reflexes (segmental) and semi-automatic activity (e.g. mastication, deglutition). Final α-motoneuron output results from these three types of interrelated sensory-motor activity that modulate each other.

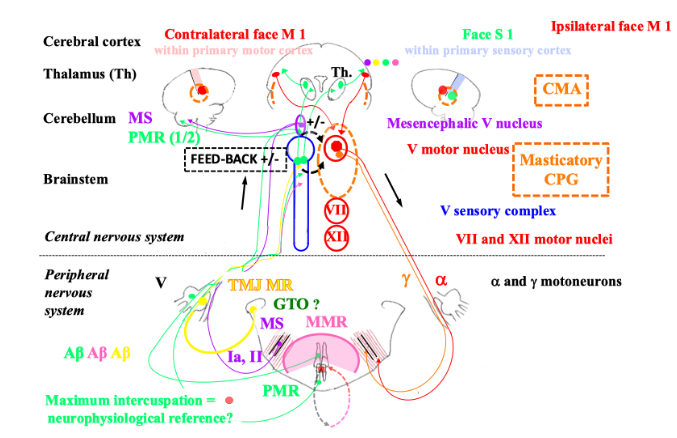

Two types of sensory-motor control modulate motor activity either feedback from peripheral origin (closed-loop) or feedforward from central origin (open-loop). Activation of the orofacial mechanoreceptors or nociceptors (in the facial skin, the mucous membrane, the temporomandibular joints -TMJ, the periodontium, the jaw-, face- and tongue-muscles) induces feedback control. Activation of these receptors fine-tunes also feedforward responses according to the peripheral state. Due to synaptic delays, feedback or reactive control is slower than feedforward or anticipatory control. Both types of control operate during mastication. Mastication is a cyclic and semi-automatic motor activity. The trigeminal (V), facial (VII), and hypoglossal (XII) rhythmic motor output is produced by the brainstem masticatory central pattern generator (CPG), and the cortical masticatory/swallow area (CMA) drive. Albeit different, the masticatory-CPG shares some similarities with the spinal locomotor-CPG, and according to the nervous system systematics, one may consider the masticatory-CPG as a brainstem segmental neuronal network whose activity is quite stereotyped. However, the intrinsic and autonomous CPG output such as a “pacemaker”, is strongly modulated both by peripheral and central input. This modulation accounts for mastication variability. Central input to the CPG is due to cerebral drive and cerebellar regulation. The main cerebral command towards the CPG comes from the orofacial sensory-motor cortex (face primary sensory cortex -face S1 and face primary motor cortex – M1, CMA), premotor cortex, anterior cingulate gyrus, insula, and basal ganglia. In the orofacial sensory-motor cortex, individual cortical neurons encode bite force and sets of neurons encode jaw gape. A model proposes that from the basal ganglia, i.e. the striatum and the pallidum, and from the cerebral cortex, a triple descending network projects towards the “behaviour control column” in the diencephalon-brainstem axis that drives the basic motivated behaviours common to all vertebrates and is essential for survival, i.e. feeding, defensive, reproductive and foraging behaviours. The “feeding behaviour column” is a hierarchically organised series of neuronal sets from the hypothalamus towards the masticatory- and swallow- CPGs that terminates on the α-motoneuron pools. These drive rhythmic V, VII, and XII α-motoneuron final output and jaw-, facial- and tongue-muscle activity during chewing. Somatosensory modulation of the masticatory-CPG activity varies according to the occlusal contacts and the characteristics of the chewed food-triggered stimulus, i.e. intensity (noxious/innoxious), duration (phasic/tonic), mucosal/dental, jaw/tooth loading or unloading and direction of tooth loading/displacement. The somatosensory modulation varies also according to the ongoing task, i.e. the background activity of the masticatory muscles (low vs high chewing force, see below), the jaw gape, and the different phases of the chewing cycle (see below). These are the opening phase, the fast-closing phase and the slow-closing phase when the jaw slows down and the teeth crush the food piece. In humans, each of these phases lasts about 400 ms, 200 ms and 400 ms, respectively. Finally, mastication depends on the individual, i.e. intrinsic factors (age, sex, occlusion, and pain/TMD), and on the food, i.e. extrinsic factors whose rheological properties change along the masticatory sequence. The changes in reactive and predictive controls parallel the changes in rheological properties allowing the adaptation of jaw muscle activity along the chewing sequence.

2.3 Feedback control and jaw motor activity

Phasic or tonic feedback Experimental setting highlights two types of feedback controls operating during mastication, either phasic, i.e. millisecond range-stimulus inducing typical jaw reflexes or tonic, i.e. hundred-millisecond range-stimulus inducing reflex-like activities. Tonic somatosensory input from periodontal mechanoreceptors and muscle spindles mainly maintains/enhances masticatory CPG output. According to the chewing phases, tonic spindle input is as follows in a decreasing order: the highest in the slow-closing phase, then in the opening one, and the lowest in the fast-closing one. Tonic periodontal mechanoreceptor input operates during the slow-closing phase. However, this effect on muscle activity varies according to the intensity of background/ongoing muscle activity. At low clenching force, tonic periodontal stimulation induces an excitatory reflex in the masticatory muscles, i.e. facilitating response, whereas at higher clenching force, this relationship tends to reverse. Indeed, the same periodontal stimulation induces an inhibitory reflex in the masticatory muscles, i.e. a protective response. However, these responses may vary according to the subjects, the masticatory muscles, the loaded teeth, i.e. incisors or molars, and the direction of loading. Contrary to the abovementioned tonic periodontal stimulation, a brief biting task inducing a phasic periodontal stimulation, triggers the jaw-opening reflex. The non-nociceptive jaw-opening reflex is triggered by phasic activation of Aβ-fibre mediated orofacial mechanoreceptors. The jaw-opening reflex may be nociceptive also and is triggered by phasic activation of Aδ- and C-fibre mediated orofacial nociceptors. Whereas tonic nociceptive input from deep tissues e.g. the TMJ or the jaw muscles, induces co-contraction of the jaw-closing and -opening muscles. Presumably, relative to Aδ-fibre, tonic C-fibre mediated nociceptive input might have here a significant role in such agonist-antagonist co-activation (see below). The original “pain adaptation model”, renamed “nociception adaptation model” within a more modern theory, describes nociception-induced motor activity in TMD and correlated jaw-muscle activity. According to this model, Aδ- and C-fibre tonic nociceptive input induces a paradoxical motor activity of jaw-closing α-motoneurons segmentally. Thus, the jaw-closing muscles exhibit an antagonistic activity during jaw-opening and a decreased agonistic activity during jaw-closing. Initially, this is an adaptative and protective mechanism that tends to immobilise the skeletal segment, i.e. the jaw. Tonic nociceptive input changes the activity of the last-order premotor interneurons. Compared with the Aδ-fibres, the C-fibres per se might have a preponderant role in nociception-induced motor activity changes. Firstly, in the biphasic nociceptive flexion withdrawal reflex, the first and short electromyographic response depends on the Aδ-fibres while the late and long one depends on the C-fibres. Furthermore, it has been shown in experimental conditions that deep tissue C-afferents have a profound motor effect, i.e. on the excitability of the flexion reflex. Indeed, a conditioning stimulus of the muscle C-afferents, produces a long-lasting increase in flexion reflex excitability. However, nociceptive input due to prolonged (24 hours) deep tissue lesion (arthritis or tenotomy) abolishes the ability of the muscle C-afferents to facilitate the flexion reflex: a trend to immobilise the skeletal segment in a “resting” position. These phenomena are due to central changes, i.e. interneuronal excitability. The jaw-unloading reflex prevents jaw shock when the breakage of the food piece provokes a sudden drop in the resistance between the jaws. When the jaw encounters resistance just before the breakage of the food piece, the jaw-closing and -opening muscles co-contract that allows braking of the jaw in increasing muscle stiffness. The agonist-antagonist co-contraction just precedes masticatory muscle inhibition. Jaw-closing α motoneuron inhibition is due to activation of the periodontal mechanoreceptors and the TMJ mechanoreceptors. Albeit not essential, the unloading of the muscle spindles might also participate in jaw closing inhibition. Additionally, the sternocleidomastoid muscle is silenced synchronously with the masticatory muscles.

2.4 Reciprocal modulation between jaw reflexes and masticatory central pattern generator

As abovementioned, the trigeminal reflexes modulate the masticatory CPG activity. Reciprocally the CPG modulates the reflexes. Thus, reflexes’ gain depends on the phase of the masticatory cycle. During the opening phase, stretch-induced spindle input must not impair jaw opening and is blocked. The myotatic reflex is gated out. However, spindle input facilitates CPG closing motor output despite muscle shortening during jaw closing where there is α-γ motoneuron co-activation. The myotatic reflex is enhanced. Similarly, the jaw-opening reflex is modulated. The low-threshold, i.e. innoxious and Aβ-fibre-mediated jaw-opening reflex is inhibited not to impair jaw-closing. However, during jaw-closing, the high-threshold, i.e. noxious (Aδ- and C-fibre-mediated) jaw-opening reflex is facilitated to inhibit jaw-closing motor output if necessary. Finally, the CPG-related modulation of the trigeminal reflexes allows them to maintain their protective role on the one hand while not hampering or even facilitating chewing on the other.

2.5 Feedforward control and jaw motor activity

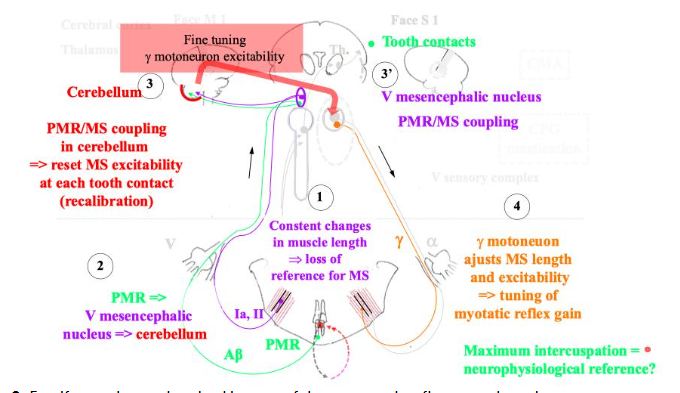

If a piece of food resists during chewing and prevents completing a masticatory cycle, just at the next cycle, additional masticatory activity is generated in anticipation to overcome the resistance of the bolus. This is the expression of feedforward control. It is suggested that the timing of the additional masticatory activity in the subsequent cycle depends on the spindles, while the magnitude of this force is controlled mainly by the spindles, and partly by the periodontal mechanoreceptors. Centrally, this control involves at least the cerebellum where there are indeed periodontal and spindle trigeminal afferent projections. Thus, the cerebellar cortex receives inputs from the spindles, and it discharges outputs through the cerebellar nuclei, inducing the feedforward response in the subsequent masticatory cycle. Though unproven, the cerebral cortex might participate also in the feedforward response through a transcortical loop, however, it would not be essential. Furthermore, the cerebellar coupling of spindle and periodontal mechanoreceptor input would allow resetting the gain of the jaw-stretch reflex at each tooth contact.

2.6 Cooperation between periodontal mechanoreceptor and muscle spindle input

Neurophysiological cooperation between the spindles and the periodontal mechanoreceptors would account for the functional significance of the tooth contacts (nicely reviewed by Türker). The spindles inform precisely about jaw movements and positions. However, spindle input and γ-motoneuron output change continuously during chewing. Thus, muscle proprioceptive input may not be reliable over time. However, the repetitive antagonistic tooth contacts which are not necessarily in maximum intercuspation, constitute time-locked absolute positions allowing calibration of spindle input. Additionally, within the periodontal mechanoreceptor and spindle coupling concept, it may be hypothesised that the maximum intercuspation defining the occlusal vertical dimension might be a particular reference jaw position where the greatest number of the periodontal mechanoreceptors is activated. However, a recent study where the maximum intercuspation has been prevented with a splint during one week, contests this central role of the maximum intercuspation in jaw-muscle function. However, it may be argued that the same study shows that after a 10-minute-training session, the precision of the closing path into maximum intercuspation remains higher than the precision into a target position far from the maximum intercuspation on a splint. This functional coupling would be possible through the projections of the spindle and periodontal afferents onto the cerebellum, thus allowing the comparison of both types of input correlated to the exact time of tooth contacts. In turn, the cerebellum alters γ-motoneuron activity appropriately to regulate the spindle sensitivity/excitability, i.e. feedforward control adjusts the gain of the jaw-stretch reflex and resets spindle afferent input. Noteworthy, in the spinal system it is known that the cerebellum is involved in feedforward control and motor learning. Besides the cerebellum, the trigeminal mesencephalic nucleus receives inputs from both types of afferents where these are coupled via electric synapses (gap junction). It is noteworthy that this nucleus plays a key role in the strict control of the occlusal vertical dimension, i.e. facial height especially during facial growth where the vertical facial proportions are acquired at five years old and maintained thereafter in humans. Additionally, the excitability of the stretch reflex is correlated to the craniofacial height and is higher in short faces than in long faces. Finally, the jaw muscle spindle afferents and the trigeminal mesencephalic nucleus coordinate the motor output of the V, VII, XII and ambiguous (glossopharyngeal nerve – IX, vagus nerve – X, and medulla part of accessory nerve – XI) motor nuclei via a common pool of premotor interneurons. Thus, besides the jaw-stretch reflex and its modulation, the integrative role of the mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus suggests it controls and coordinates also the more complex orofacial motor activities such as mastication, deglutition, respiration, vocalisation, and feeding behaviour. The functional significance of this nucleus in connection with the dental occlusion would account for its involvement in the abovementioned control of facial height. Indeed, it is admitted that orofacial functions control partly craniofacial growth/morphogenesis in complex interrelationships with the genetic and hormonal determinants. In adaptative, i.e. function-related facial growth, the “cybernetics theory” of Petrovic and Stutzmann suggests that the dental occlusion plays a key regulatory role such as a “comparator” in the control of the upper- and lower-jaw relationship and morphogenesis. Thus, antagonistic tooth contacts during mastication and mature deglutition (whereas in immature deglutition there is no tooth contact) have a significant proprioceptive role in jaw-muscle function. Furthermore, given the role of tooth contacts in anticipatory and retroactive jaw-muscle control, from a neurobiological perspective (neurophysiology and neuroplasticity) it can be assumed that their role might outlast their strict duration per se. If this comes true, it is remarkable given the short duration of these contacts per 24-hour cycle: 26 min per 24 hours, i.e. 1.8% of one 24-hour cycle. However, it can be assumed that as in any skilled training program, the repetitions and their quality are more significant than the absolute duration of the training. It would promote adaptive neuroplasticity in the brain. Additionally, the maximum intercuspation even if rarely attained, appears to be a reference position in a neurophysiological point of view. However, given the great adaptability of the masticatory apparatus correlated with brain adaptive neuroplasticity, this position can be changed for therapeutic purposes in healthy (non-pain) subjects. However, in pain patients, this adaptability would be lost. It explains why occlusion modification is not recommended in these patients, at least until pain and dysfunction are managed.

2.6 Interrelationship between feedback and feedforward control

It used to be considered that feedback control which is supposed to be quite “slow” operates mainly in posture and slow-motion control, whereas faster feedforward control operates mainly during fast movements. Even though the masticatory rhythm is quite fast, i.e. about 1 Hz in humans, the trigeminal motor system used to be considered to work mainly as a closed-loop system. This assumption was based on trigeminal control relying on proprioceptive and exteroceptive input only and the absence of visual assistance. Whereas this assistance participates in feedforward (open-loop) control of visually guided arm/hand movements in the spinal system. However, it is worth noting that while the chewing rhythm increases, there is a shift from feedback towards feedforward control. Noteworthy in the spinal system assisted with the visual and/or vestibular system, feedback and feedforward controls are not mutually exclusive but cooperate, even for fast movements. Thus, even though the trigeminal system relies on proprioceptive and exteroceptive (and occasionally nociceptive) input only, it is known that feedback and feedforward controls cooperate during mastication. This accounts for the continuous adaptation in jaw muscle activity throughout the masticatory sequence, to the changing rheological properties of the food bolus, i.e. hardness, plasticity, viscosity and elasticity. In a protocol where “acute” experimental occlusal interferences are created on the working-side in healthy subjects, the kinematics of the chewing cycles changes immediately with subsequent habituation to avoid the occlusal interferences. This adaptation process requires a priori both feedback and feedforward controls. In locomotion, such dual control proceeds during motor learning intended to clear an obstacle. This dual control may involve both the suprasegmental system, i.e. the basal ganglia, the cerebellum and the cerebral cortex, and the segmental motor system, i.e. the spinal cord. According to a theoretical model predicting shared feedback and feedforward controls in rhythmic and CPG-driven movements such as locomotion, it is suggested that purely segmental and CPG-dependant combined control would allow adaptation to unexpected changes. Chewing adaptation may be due to similar dual feedback and feedforward control depending on the segmental sensory-motor system and the masticatory CPG. Indeed, as abovementioned, the jaw reflexes are modulated and their gain/excitability is centrally reset via CPG-related feedforward control. Afferent feedback modulates jaw reflex excitability also.

2.7 Cooperation between jaw- and neck-motor system

Jaw and neck motor behaviours are coordinated. A normal head extension- and flexion -movement parallels jaw-opening and -closing, respectively during voluntary or chewing jaw opening-closing cycle. Furthermore, just at the start of the first jaw opening-closing cycle, there is an anticipatory head extension movement, i.e. feedforward control of the neck muscles anticipates jaw opening just as automatic postural control of the neck muscles anticipates arm flexion.

3. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY: SENSORY-MOTOR CONTROL IN TEMPOROMANDIBULAR DISORDERS AND OTHER MUSCULOSKELETAL DISORDERS

3.1 Proprioceptive reflexes: stretch/myotatic trigeminal or spinal reflex

Musculoskeletal disorders involving the trigeminal or the spinal system In clinical masticatory muscle pain condition, the excitability, i.e. the size of the jaw-closing muscle electromyographic response of the trigeminal stretch reflex is either unchanged or decreased. However, these results must be considered cautiously because patient groups are not always homogenous: muscle pain with or without TMJ pain; only two studies involve pure myogenous TMD patients. In addition, the type of pain, i.e. either nociceptive or nociplastic, is not specified according to the current criteria classifying TMD. Nevertheless, it may be said that trigeminal stretch reflex excitability or gain is either unchanged or decreased in muscle-type TMD. This reflex is also depressed in patients with TMJ non painful disc displacement with or without reduction. Similarly in MSD involving the spinal system e.g. in knee anterior cruciate ligament strain and in patellofemoral pain also called anterior knee pain, quadriceps muscle (knee extensor muscle) stretch reflex excitability is decreased as is H-reflex excitability evaluating α-motoneuron excitability. Additionally, in patellofemoral pain, the decrease in α-motoneuron excitability is correlated with the increase in pain intensity and chronicity. It is not known whether the α-motoneuron decrease in excitability is a cause, i.e. a risk factor or a consequence, i.e. a prognosis factor, of pain. The stretch reflex timing is either unchanged or increased. Interestingly, this delay is positively correlated with the length of symptoms and the prognosis: the longer the delay, the older the symptoms, the worse the prognosis. Similarly, H-reflex excitability is decreased in shoulder pain (trapezius muscle) and lateral ankle sprain (soleus muscle). However, in low-back pain, the longissimus muscle (spinal erector muscle) stretch reflex gain is increased and this increase is correlated with pain-related psychological stress. It is known that in MSD, such as low-back pain or neck pain, the motor behaviour between the deep and the superficial muscles is different where the superficial muscles compensate for impaired deep muscle activity. Thus, it might be the reason why the reflex gain of the longissimus muscle is increased in low-back pain, and in the deepest muscles it might be different. Thus, mostly in clinical muscle pain, stretch reflex excitability or gain may be unchanged or decreased. If stretch reflex gain is increased, it might be due to compensatory activity. Whereas in experimental muscle pain in humans, i.e. tonic nociceptive pain, the stretch reflex excitability is increased either in the trigeminal or spinal system. Additionally in experimental muscle pain condition, the increase in stretch reflex excitability is not due to an increase in α-motoneuron excitability as H-reflex excitability is unchanged either in the spinal or trigeminal system. Whereas in experimental tonic muscle pain condition in animals, the trigeminal stretch reflex excitability tends to decrease similarly to clinical conditions in humans. However, the changes are not uniform in the same experiment. The variability in the stretch reflex modulation might be due to variability in premotoneuronal inhibition. The reason for the discrepancy between the experimental conditions in humans and animals, is not known. It may be due to the different experimental settings and pain duration, i.e. 15 mn in humans vs 120 mn in animals where the latter would mimic clinical pain better than the former.

3.2 Protective reflexes: trigeminal “jaw-opening” reflex or spinal flexion/withdrawal reflex

Musculoskeletal disorders involving the trigeminal or the spinal system The “elevator-inhibition reflex” the human equivalent of the jaw-opening reflex in animals (see above), has been studied in muscle-type TMD patients. There is a trend towards a decrease of the silent period of jaw-closing muscles. However, these results must be considered cautiously because patient groups are not always homogenous: muscle pain with or without TMJ pain. Likewise in tonic experimental jaw muscle pain model in humans or in animals the silent period is reduced. Thus, in muscle pain involving the trigeminal system, the protective reflex is depressed. On the other hand, in clinical and chronic pain conditions including MSD involving the spinal system, the nociceptive reflex threshold is decreased. Additionally, in low-back pain and neck-pain the reflex receptive fields are enlarged. Thus, it has been hypothesised the increase in excitability of the nociceptive flexion reflex would be due to “central/spinal hyperexcitability”. The latter would account for pain hypersensitivity (lower pain threshold, allodynia, hyperalgesia and extension of pain) in chronic pain patients.

3.3 Feedforward control in musculoskeletal disorders

Feedforward control is poor in MSD such as low-back pain and neck pain. In whiplash-associated disorders, the jaw-neck coordination is disturbed. Noteworthy, the initial anticipatory head extension movement before the first jaw opening-closing cycle, is delayed. This suggests a deficit in feedforward control as it is also in arm-neck coordination in neck pain. In neck pain, this deficit correlates with pain intensity. However, as far as it is known in TMD patients, a putative deficit in feedforward control has not been studied yet during mastication in the masticatory apparatus. If this were true it might partly account for the risk of functional maladaptation due to occlusal change in pain patient e.g. TMD, whereas healthy subject adapts well to occlusal changes.

3.4 Unreliable/poor sensory-motor regulation in musculoskeletal disorders?

The results of the abovementioned studies about sensory-motor regulation are not unequivocal. However, proprioceptive feedback, i.e. myotatic reflex, tends towards hypo-excitability except maybe when superficial muscles are involved (compensatory activity). Additionally, feedforward control is delayed. Thus, it can be hypothesised that both types of control are poor and unreliable in MSD. As far as exteroceptive feedback, i.e. (nociceptive or not)-flexion/protective reflex, is concerned, it would promote pain-avoiding behaviour. Central sensitisation is a widely accepted concept in chronic musculoskeletal pain that can account for reduced nociceptive reflex threshold. However, the threshold may be also unchanged or even increased in some cases. This fact cannot be explained by central sensitisation which in humans can only be assumed but not deeply explored like in animals in laboratory setting. The non clearcut results about excitability of sensory-motor regulation might lie in heterogeneity of the patients and/or MSD. Indeed, musculoskeletal painful conditions may be either nociceptive, nociplastic or neuropathic type and TMD-related pain may be either nociceptive or nociplastic type. Additionally, the variability in excitability of the sensory-motor regulation could reflect the variability in motor activity in MSD. According to current models, pain-induced motor changes in MSD exhibit a great interindividual variability contrary to the initial theories, i.e. pain/spasm/pain vicious cycle theory (hyperactivity) and pain adaptation model (paradoxical activity), that described quite stereotyped motor activity. Currently, it is rather recognised that pain-(and stress)-related motor activity is modulated at each level of the nervous system, i.e. segmental and suprasegmental, and between each of these levels through bottom-up and top-down modulation. Thus, between-subject variability in motor strategies is greater in patients than in healthy subjects. However, the within-subject muscle recruitment variability in MSD would be lower in patients than in controls even though this recruitment is not stereotyped as initially conceptualised. With this in mind, some general rules can be drawn. First, compared to reciprocal inhibition motor strategy, the co-activation motor strategy is favoured in MSD allowing to increase muscle stiffness. Second, the superficial muscles compensate for deficiency of the deep muscles and exhibit some hyperactivity. Thus, it may be suggested that both initial concepts, i.e. pain-adaptation renamed nociception-adaptation model and vicious cycle theory might be two sub-systems of a wider concept about adaptation to pain as proposed by Murray and Peck in the “integrated pain adaptation model”. Finally, the predominance of co-activation motor strategy might be due to abovementioned poor feedback and feedforward control. Indeed, it is known that compared to reciprocal inhibition, co-activation is a default strategy when sensory-motor regulation is poor and when there is uncertainty about the task. Interestingly, it is suggested that the cerebellum would play a key role in the switch between both of these motor strategies where stiffness would be the controlled variable.

3.5 Proprioceptive deficit in musculoskeletal disorders

In chronic low-back pain, it is accepted that there may be a proprioception deficit at least in some patients. Similarly, in the masticatory apparatus, the abovementioned poor sensory-motor regulation in TMD might reflect a deficit in proprioception, i.e. the sense of position and the sense of force of a musculoskeletal segment, in this case, the jaw. Indeed, the control of jaw clenching force is less precise in muscle-type TMD and TMJ-type TMD than in healthy subjects.

4. CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

4.1 Partial trigeminal reciprocal inhibition principle: pathophysiological consequence

According to the “pain adaptation model” in TMD, there is jaw-closing and -opening muscle co-activation during the opening that can induce jaw-opening limitation and/or deflexion. This would be due to activation and/or disinhibition of the jaw-closing α-motoneurons during opening. Clinically and as far as it is known, muscle pain-induced “jaw closing limitation” has never been described. Presumably, this is because in healthy state, the jaw-opening α-motoneurons are not hyperpolarised during closing. Thus, it may be hypothesised that in painful conditions, the jaw-opening α-motoneurons cannot be disinhibited during closing accounting for the absence of “nociception induced jaw closing limitation”. However, this assumption needs investigations.

4.2 Temporomandibular disorder and tongue dysfunction

Tongue dysfunction appears to be a TMD co-occurrent condition. During the oropharyngeal phase of swallowing, the jaw requires stabilisation to be a fulcrum for the elevation of the hyoid apparatus and the tongue. In mature swallowing, the jaw is stabilised by jaw-closing muscle contraction while facial muscle activity is minimal. Whereas in immature swallowing, the reverse applies: the jaw-closing muscle activity is reduced and compensated for by increased facial muscle activity. Fassicollo et al. evaluated the jaw-muscle activity in deglutition in TMD patients. They found a prolonged activity time of deglutition. Additionally, compared to controls in TMD patients, the relative activity of jaw-closing muscles is increased and superior to controls. At first glance, this conflicts with the pain adaptation model where the agonistic jaw-closing muscle activity is reduced (accounting for the decreased biting/chewing force). However, one can speculate that assessing the relative activity rather than the absolute one biased the results. The relative activity is increased artificially as the absolute activity is divided by the maximum jaw-closing muscle activity which is decreased in TMD patients compared to controls. However, in referring to the absolute activity, it remains inferior in TMD patients compared to controls. Thus, one can hypothesise that in line with the pain adaptation model, the decreased agonistic activity of jaw-closing muscles in TMD patients could account for immature deglutition in TMD patients. This hypothesis requires further investigation.

4.3 Target of functional rehabilitation in temporomandibular disorder

Rhythmic and cyclic activities such as locomotion, respiration, and mastication may be subject to entrainment which is defined as “a synchronization of an endogenous oscillator to external periodic events”. This synchronization might parallel an improvement in sensory-motor control, i.e. in feedback and feedforward control. However, it is not known how sensory-motor control would be more efficient in such conditions. It might be correlated to brain adaptative neuroplasticity paralleling functional improvement. It may be suggested also that the cerebellum which is involved in motor learning and feedforward control would play a key role. One could take advantage of this knowledge to develop skill-training programs where motor task repetition follows a very regular “metronome-like” rhythm. Indeed, rhythmic (1 Hz) and passive (with an operator) jaw mobilisation induces immediately a pain-relief and a decrease in jaw-opening limitation. Thus, one can speculate that jaw-closing muscle co-contraction decreases during opening. Additionally, compared to habitual mastication, standardised mastication according to (1 Hz)-rhythm appears to improve masticatory muscle coordination in TMD patients. It is hypothesised that skilled training induces a switch from co-activation towards reciprocal inhibition in improving sensory-motor regulation efficiency in TMD patient. Additionally, exercise-induced proprioceptive input might gate-out nociceptive input according to the gate-control theory at least in TMD-related nociceptive-type pain. It is also known that proprioceptive input and bottom-up mechanisms preserve cortical networks, i.e. adaptive neuroplasticity and prevents maladaptive plasticity. Furthermore, controlled chewing exercises would induce pain relief in masticatory muscle pain patients whereas habitual (non-standardised) mastication induces pain. This may be due to blood hypoperfusion highlighted by a deficit in oxygen extraction in painful jaw muscles. Oxygen deficiency could account for the cytochrome C oxidase and ATP deficiency in the muscle fibre mitochondria of painful muscle where there would be an “energy crisis”. Conversely, in TMD, it is suggested that standardised mastication exercises might increase blood perfusion in jaw muscles correlated with putative beneficial biochemical events in the muscle fibres. Once the several week exercise-program is accomplished, it may be hypothesised that usual and daily activity, i.e. pain-free mastication and if possible mature deglutition, would maintain the benefit of the rehabilitation both as far as muscle physiology (hemodynamic, biochemical function) and sensory-motor activity are concerned. Additionally, in such a program, it may be suggested to rehabilitate both the jaw muscles and the tongue if tongue dysfunction is present. Finally, it should favour feeding behaviour which may be impaired both quantitatively and qualitatively if pain is severe.

4.4 Temporomandibular disorder and changes in dental occlusion: a case of maladaptation?

Healthy, i.e. pain-free subjects adapt well to changes in dental occlusion. In contrast, patients with TMD history may not adapt to changes in dental occlusion. They may develop signs and symptoms of TMD. In healthy subjects, one may suggest that the adaptation process is due to efficient sensory-motor regulation, whereas in TMD patients, sensory-motor regulation would be poor thus preventing adaptation. In healthy subjects, this would be possible thanks to brain adaptive neuroplasticity, whereas in painful conditions, this might be due to maladaptive plasticity. It explains why it is strictly recommended not to change dental occlusion in painful conditions such as TMD as outlined in current guidelines due to the poor functional adaptability of these patients. On the contrary, it should be waiting for pain relief through first-line non-invasive, conservative and multimodal management: cognitive behavioural approaches (counselling, patient education, change in detrimental habits), physical therapy (jaw, neck and/or tongue exercises, massages), pharmacotherapy, and oral splint. The latter proceeds a priori mainly via placebo effect as its biological and specific effects if any, are only suppositional. In disrupting jaw muscle activity, the splint might favour the variation in the intramuscular recruitment motor pattern.

Conclusion

Currently, dental occlusion must be considered not only from a biomechanical point of view but also in a neurobiological (i.e. neurophysiology and neuroplasticity) perspective. It can be assumed that despite the very short duration of occlusal contacts per nycthemer (less than 2% of the time except in case of bruxism), these contacts exhibit a significant role in the neurobiology of jaw function. It may be due to the functional coupling of periodontal and muscle spindle input and the role of this input on brain neuroplasticity to allow adaptation to lifelong changes in dental occlusion. Dental occlusion is no longer considered an aetiological factor in TMD, but some at-risk pain patients may not be able to adapt to changes in dental occlusion. In healthy state, adaptation is possible thanks to efficient sensory-motor regulation and brain adaptive neuroplasticity. In pain patients, it is suggested that sensory-motor regulation would be less efficient as evidenced by changes in feedback and feedforward control and maladaptive brain neuroplasticity. However, the brain’s neurobiological causes of changes in sensory-motor regulation require investigations. Finally, it is hypothesised that functional rehabilitation in MSD, such as TMD, could improve sensory-motor regulation efficiency thanks to a highly regulated rhythm of movement repetitions (i.e. skilled training).

Conflicts of interest:

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

“`