Sub-Diaphragmatic Causes of Subcutaneous Emphysema

What Lies Beneath: Sub-diaphragmatic causes of subcutaneous emphysema A Review

Matthew G. Dunckley, FRCS *¹, Aung Phyo Thant, MBBS ¹, Jacek Adamek, FRCS ¹

¹ Department of General Surgery, Dartford & Gravesham NHS Trust, Dartford, UK.

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 July 2025

CITATION Dunckley, MG., Thant, AP., et al., 2025. What Lies Beneath: Sub-diaphragmatic causes of subcutaneous emphysema A Review. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(7). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i7.6592

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i7.6592

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

Air in the subcutaneous tissues, commonly described as subcutaneous emphysema, creates a distinctive clinical sign on palpation. Usually, this results from an air leak from the airways or lungs forcing air into the mediastinum and in between soft tissue planes. This review aims to draw attention to bowel perforations below the diaphragm as an alternative origin of subcutaneous emphysema. Reference to numerous case reports illustrate a variety of presentations and causes. Delayed recognition and treatment of bowel perforation can have serious, potentially life-threatening, consequences. Patients presenting with subcutaneous emphysema without an obvious intra-thoracic cause should lead the clinician to consider acute intra-abdominal pathology, such as bowel perforation, especially after endoscopic procedures. Early recognition of this phenomenon can be life saving.

Keywords

subcutaneous emphysema, bowel perforation, mediastinum, acute intra-abdominal pathology, endoscopic procedures

Introduction

Subcutaneous emphysema (SCE), sometimes known as describes gas within the subcutaneous tissue planes of the body. It is a rare but striking clinical sign characterised by swelling and crepitus under the skin. As subcutaneous emphysema is usually found in the neck and thorax, acute thoracic or cervical pathology is often suspected. Indeed, it is most commonly caused by air escaping from disrupted pleurae or airways into the mediastinum, such as in acute pneumothorax or thoracic trauma.

Similarly, it is somewhat expected in cardiothoracic surgery or after thoracic interventions, such as the insertion of intercostal chest drains. In these instances, the origin of the air leak is predictable and anticipated so it can normally be managed during the immediate post-operative period. Air from thoracic organs is normally not contaminated so does not typically pose a threat of sepsis and will dissipate with minimal consequences to the patient. However, another potential source of air in the mediastinum is from perforation of the oesophagus, often rapidly leading to subcutaneous emphysema. Oesophageal perforations may occur after violent vomiting syndrome, forced Valsalva manoeuvre or during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Hence, the recent medical history may suggest oesophageal perforation as a cause of subcutaneous emphysema, which can then be confirmed by imaging, such as a water soluble contrast study.

What is less known, however, is that visceral air from sub-diaphragmatic gastrointestinal perforations can track into subcutaneous tissue planes from the abdomen, probably entering the mediastinum via the diaphragmatic hiatus and causing subcutaneous emphysema. Retroperitoneal perforations can be particularly difficult to identify as they may not initially cause the classic clinical signs of intraperitoneal visceral perforations, such as acute peritonitis, leucocytosis or pyrexia. Instead, they may first present non-specific pain, sometimes radiating to the back, with subcutaneous emphysema and subsequently of unknown origin. Further diagnostic confusion can occur because air from within the abdomen may also move to parts of the body anatomically distant from its origin, such as the neck and even the orbit. One recent case report even describes a patient presenting to otolaryngologists (ear, nose and throat surgeons) with a hoarse voice secondary to disseminated subcutaneous air arising from a perforated sigmoid colon.

The anatomical basis for subcutaneous air movements from within the abdomen is not always clearly understood as it does not always pass into the upper body via the mediastinum. For instance, several case reports have described bowel perforations causing subcutaneous emphysema in the scrotum and lower limbs. In these cases, the air may have passed out of the abdominal cavity via the deep inguinal ring in a similar way to an inguinal hernia. It could also be envisioned that if the patient is mainly supine following an intestinal perforation, the gas could track equally inferiorly as superiorly, depending on the path of least resistance. Unsurprisingly, such atypical presentations can cause diagnostic confusion and delays in treatment. At its most serious, such delayed diagnoses of bowel perforation can result in life-threatening consequences, such as advanced sepsis or tension pneumothorax.

Radiological diagnosis of subcutaneous emphysema

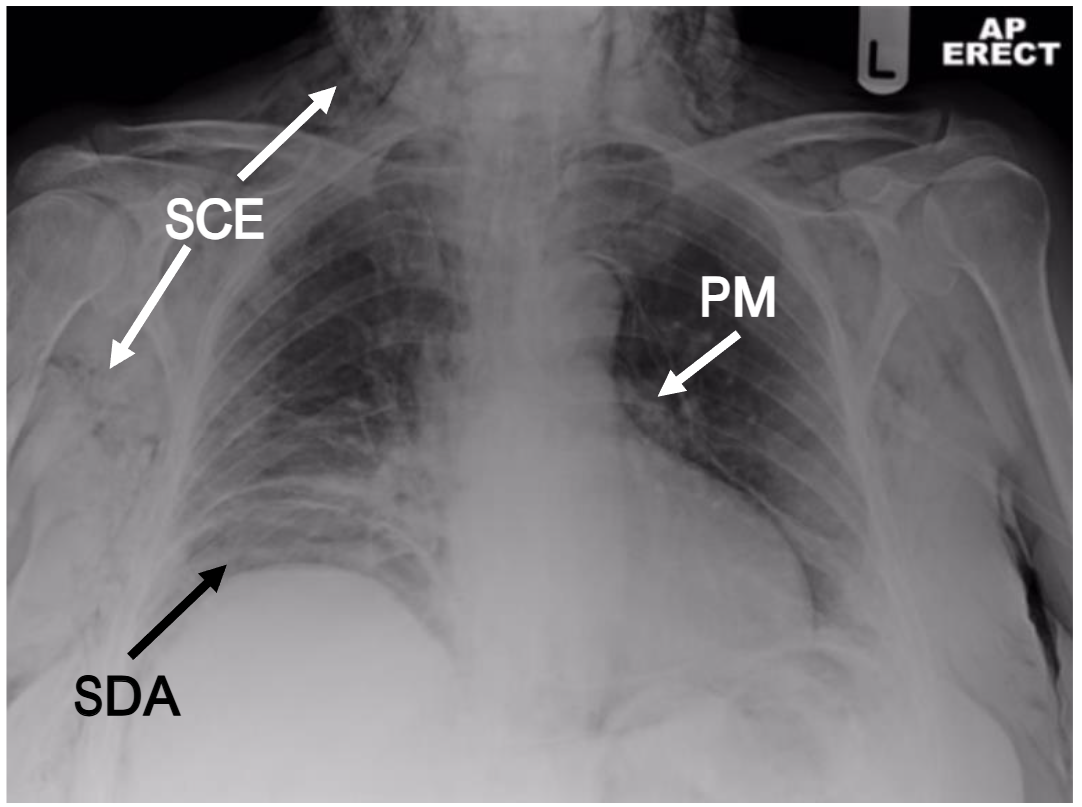

In most developed countries, there is less reliance on simple radiographs but an appropriately exposed radiograph can reveal subcutaneous emphysema clearly (see Figure 1) and may suggest a cause.

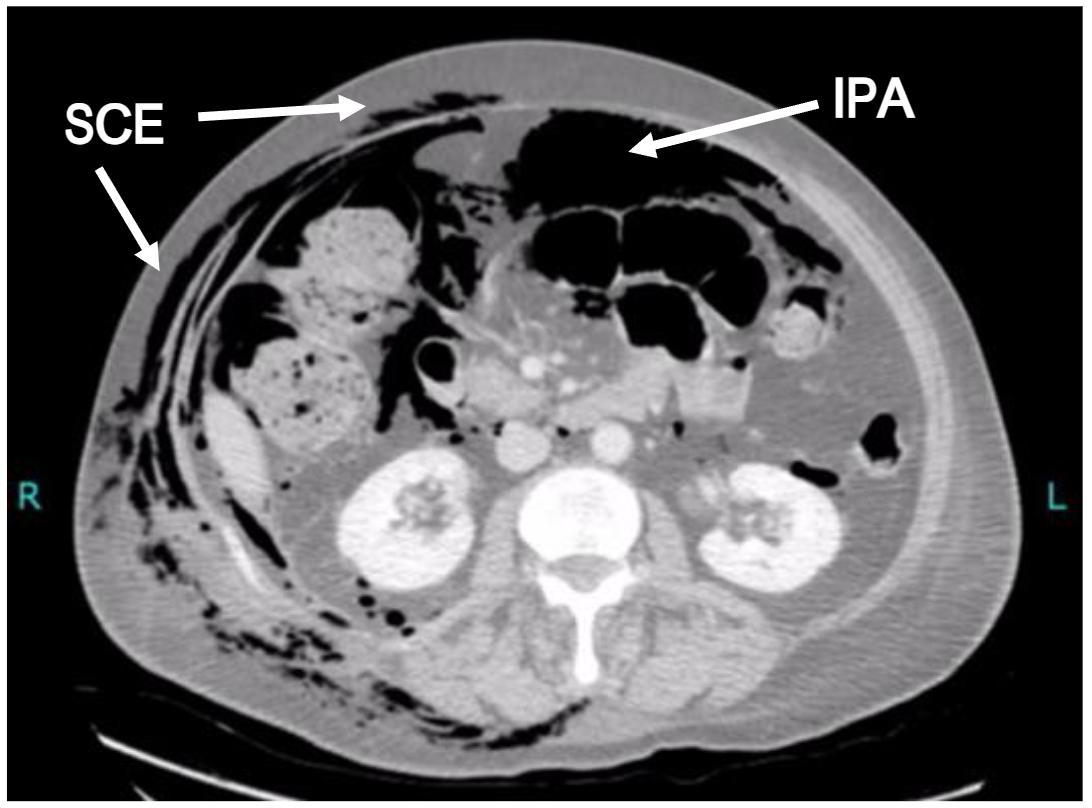

However, computed tomography (CT) is becoming a much more common early diagnostic tool as the rapidity, yield and specificity of radiological information is significantly greater. In the case of subcutaneous emphysema, CT imaging may reveal its anatomical site and extent, it may still be extremely challenging for the reporting radiologist to identify its origin in the absence of relevant clinical information or intra-abdominal stigmata. Indeed, subcutaneous emphysema of the head, neck and thorax may not even prompt the clinician to request inclusion of the abdomen. Occasionally, however, the information provided by an adequate CT scan is invaluable and can lead to a rapid diagnosis (see Figure 2). This review aims to encourage clinicians to include sub-diaphragmatic causes of acute subcutaneous emphysema within their differential diagnosis.

Spontaneous bowel perforation and subcutaneous emphysema

Spontaneous bowel perforations can result from trauma (accidental or iatrogenic), ischaemia, diverticulae or carcinomas. Although it is a rare phenomenon, subcutaneous emphysema develops more commonly from colonic than small bowel perforations. This is probably due to the greater volumes of gas within the colon, high intra-luminal pressures and a significant proportion of the colon lying in a retroperitoneal position. Left sided colonic perforations account for the vast majority of case reports of subcutaneous emphysema secondary to perforation, especially involving the sigmoid. Rarely, however, subcutaneous emphysema has been reported from small bowel perforations, such as the description of a 14 year old patient in whom a retained peritoneal shunt catheter led to erosive perforations of the jejunum. Diop et al. report the case of a patient presenting with subcutaneous emphysema associated with a liver abscess, both of which were found to be secondary to perforation of the adjacent transverse colon. Even rectal perforations can cause this phenomenon, where it is more likely to occur outside the pelvis.

Spontaneous sigmoid colon perforations are commonly secondary to diverticular disease, especially in the elderly, as diverticulae are natural weak points along the colon wall and may be dilated by the pressure of constipated stool and excessive flatus. As a result, it is unsurprising that there are numerous reported cases of subcutaneous emphysema arising from sigmoid diverticulosis. Inflammation of the bowel can lead to weakness and localised ischaemia of the bowel wall. This is reflected in case reports of subcutaneous emphysema arising in patients with inflammatory conditions, such as ulcerative colitis and appendicitis.

Colonoscopy and Subcutaneous emphysema

Colonoscopy is an endoscopic procedure performed for screening, diagnostic or therapeutic purposes. It is known that trauma from the endoscope or from polypectomy can lead to bowel perforation, especially in the presence of diverticular disease, strictures or polyps/tumours. Bowel perforations during colonoscopy occur in 0.1% – 0.2% of cases, rising to 1% – 2% where polypectomy is performed, especially in the elderly or where large polyps are involved. Such perforations are notoriously under-recognised at the time and may take hours or even days to be diagnosed as most colonoscopies are performed as day cases and it is often hard to distinguish between the usual discomfort of the endoscopy and the symptoms from a small perforation. Perforations causing subcutaneous emphysema have been reported secondary to endoscopic balloon dilatation of colonic strictures, endoscopic mucosal resection of polyps and polypectomy. However, this can also occur from diagnostic colonoscopies even without interventions.

If one considers that as much as 8 litres of carbon dioxide are insufflated in a typical colonoscopy, ongoing intracolonic insufflation following an unrecognised perforation can lead to very large volumes of gas being pumped into the peritoneum or retroperitoneal space. This can lead to life-threatening complications, such as tension pneumothorax. There has been an increase in performing colonoscopy under general anaesthesia over the past 25 years, from approximately 8% to 30% in some centres. However, while this eliminates the pain and discomfort of colonoscopy for the patient, it increases risks and can further delay the recognition of visceral perforation, especially as anaesthesiologists are more likely to consider subcutaneous emphysema under general anaesthesia as arising from ventilator-induced lung trauma.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography and subcutaneous emphysema

Endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) is a highly skilled endoscopic procedure used to visualise the duodenal ampulla and the biliary tree for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. The technique is used to biopsy lesions of the bile duct or ampulla and to retrieve or release gallstones in the common bile duct. Strictures of the peri-ampullary ducts may also be dilated or widened by sphincterotomy, with or without deploying a biliary stent.

Although there is a risk of duodenal perforation during ERCP, it occurs in less than 1% of procedures and often retroperitoneal. As with other retroperitoneal perforations, clinical signs may be subtle but may include the development of subcutaneous emphysema. Although it is a rare complication following ERCP, case reports suggest that subcutaneous emphysema in these patients typically tracks to the thorax, neck or face and may be sufficiently extensive to cause airway compromise or pneumothorax. It has even been reported, bizarrely, in the lower extremities after ERCP, but the anatomical mechanism of this is obscure. Other complications of ERCP, such as pancreatitis, may also be present and may complicate the diagnosis. Nevertheless, it would appear that the development of subcutaneous emphysema following ERCP, as with other endoscopic procedures, should be considered diagnostic of a perforation.

Management

Rapid diagnosis of a bowel perforation is key to successful treatment. Once a visceral perforation has been diagnosed, the typical management involves proceeding to emergency laparoscopy or laparotomy with washout of intraperitoneal contamination and drainage. There is an overall mortality of 7% rising to as much as 19% within the first 28 days if faecal peritonitis is also present. Up to 30% of these patients require a permanent colostomy but early diagnosis reduces the risk of a stoma by approximately 70%. These data mainly come from the commonest causes of perforation, especially perforated diverticular disease or stercoral perforations, where spillage of faeces and intra-colonic bacteria rapidly lead to intra-abdominal sepsis. Importantly, however, most reports of subcutaneous emphysema in association with colonic perforations involve leakage of isolated intra-luminal air in the absence of significant faecal contamination. Moreover, in the cases discussed above involving colonoscopic perforations, patients will have taken bowel preparative purgatives, reducing or eliminating the presence of intra-luminal faeces. This implies that such perforations are either relatively small or rapidly sealed by omentum. In the case of retroperitoneal perforations, it is possible that the restricted space between tissue planes acts to tamponade luminal leaks against faeces but allow the passage of gas.

Therefore, although the subcutaneous air comes from within the intestinal lumen, most bowel perforations causing subcutaneous emphysema can be managed conservatively. Most of the gas within the subcutaneous tissue planes will gradually resolve within days. The early use of antibiotics is recommended to prevent potential sepsis, although there is not published evidence for this at present. Indeed, where localised septic collections develop subsequently, that may be amenable to drainage by interventional radiological approaches without surgery. In those cases of subcutaneous emphysema of abdominal origin which require operative management, either for sepsis control or bowel resection, the additional risks of anaesthesia should be considered. General anaesthesia may increase the risks of pneumothorax and tension pneumothorax during artificial ventilation of these patients. In these circumstances, the patient should have unilateral or bilateral intercostal chest drains inserted prior to the anaesthetic in order to mitigate the risks of these complications.

Summary

The early recognition of the signs and symptoms of bowel perforations and prompt intervention is key to improving patient outcomes. Subcutaneous emphysema should prompt a full examination and, especially in the absence of pneumothorax, should raise the possibility of a visceral perforation as a significant differential diagnosis. We hope that this review raises awareness among physicians and emergency practitioners in order to prevent sepsis and save lives.

Conflict of Interest Statement:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Statement:

None.

Acknowledgements:

None.

References:

- Ball CG, Ranson K, Dente CJ, Feliciano DV, Laupland KB, Dyer D, et al. Clinical predictors of occult pneumothoraces in severely injured blunt polytrauma patients: a prospective observational study. J Injury. 2009; 40:44-47.

- Dubin I, Gelber M, Schattner A. Massive Spontaneous Subcutaneous Emphysema. Am J Med. 2016; 129:e337 8.

- Melhorn J and Davies HE. The management of subcutaneous emphysema in pneumothorax: A literature review. Curr Pulmonol Reports. 2021; 10:92 97.

- Jones P, Hewer RD, Wolfenden HD, Thomas PS. Subcutaneous emphysema associated with chest tube drainage. Respirology. 2001; 6:87 9.

- Gimenez A, Tomás Franquet T, Jeremy J. Erasmus JJ, Santiago Martínez S, Estrada P. Thoracic complications of esophageal disorders. Radiographics. 2002; 22: S247-58.

- Maunder RJ, Pierson DJ and Hudson LD. Subcutaneous and mediastinal emphysema. Pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Arch Intern Med. 1984; 144:1447-53.

- Abdalla S, Gill R, Yusuf GT and Scarpinata R. Anatomical and radiological considerations when colonic perforation leads to subcutaneous emphysema, pneumothoraces, pneumomediastinum and mediastinal shift. Surg J 2018; 4:e7-e13.

- Catarino PA and Smith EE. Subcutaneous emphysema of the thorax heralding colonic perforation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001; 71:1341-1343.

- Janczak D, Ziomek A, Dorobisz T, Dorobisz K, Janczak D, Pawlowski W and Chabowski M. Subcutaneous emphysema of the neck, chest and abdomen as a symptom of colonic diverticular perforation into the retroperitoneum. Kardiochir Torakochir Polska. 2016; 13:55-57.

- Schmidt GB, Bronkhorst MW, Hartgrink HH and Bouwman LH. Subcutaneous cervical emphysema and pneumomediastinum due to a lower gastrointestinal perforation. World J Gastroent. 2008; 14:3922-3923.

- Hartford-Beynon JS, Kadambande S and Rassam S. Surgical emphysema of the orbit associated with pneumoperitoneum. Br J Anaesth 2011; 105:151.

- Bormann SL, Wood R and Guido JM. Hoarseness due to subcutaneous emphysema: a rare presentation of diverticular perforation. J Surg Case Rep. 2024; 10.1093/jscr/rjad566.

- Fosi S, Giuricin V, Girardi V, Di Caprera E, Cosatanzo E, Di Trapano R and Simonetti G. Subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum, pneumoretroperitoneum and pneumoscrotum: Unusual complications of acute perforated diverticulitis. Case Reports Radiol. 2014; 10.1155/2014/431563.

- Verma R. Case report: A rare case of colonic perforation presenting as subcutaneous emphysema of lower chest, anterior abdominal wall and scrotum. Santosh Univ J Health Sci. 2015; 1:47-49.

- Haldeniya K, Krishna SR, Raghavendra A and Kumar Singh P. Pneumomediastinum, pneumoperitoneum and pneumo-scrotum with extensive increasing subcutaneous emphysema: a rare presentation of colonic perforation. Egypt Liver J. 2023; 13:68-70.

- Saldua NS, Fellars TA and Covey DC. Bowel perforation presenting as subcutaneous emphysema of the thigh. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010; 468:619-623.

- Ioannidis O,KakoutisE, ParaskevasG,Chatzopoulos S, Kotonis A, Papadimitriou N, Konstantara A and Makrantonakis A. Emphysematous cellulitis of the left thigh caused by sigmoid diverticulum perforation. Ann Ital Chir. 2011; 82:217-220.

- Velickovic M and Hockertz T. Perforation of an occult carcinoma of the prostate as a rare differential diagnosis of subcutaneous emphysema of the leg. Case Reports Ortho. 2016; 10.1155/2016/5430637.

- Tosi M, Al-Awa A, Raeymaeckers S and De Mey J. Subcutaneous emphysema of the extremities: Be wary of necrotising fasciitis, but also consider occult rupture or perforation. Clin Case Rep. 2021; 9:e04831.

- Kipple J. Bilateral tension pneumothoraces and subcutaneous emphysema following colonoscopic polypectomy: A case report and discussion of anaesthesia considerations. AANA Journal. 2010; 78: 462-467.

- Zeno BR, Sahn SA. Colonoscopy associated pneumothorax: a case of tension pneumothorax and a review of the literature. Am J Med Sci. 2006; 332:153-155.

- Montori G, Di Giovanni G, Mzoughi Z, Angot C, Samman S, Al Solaini L and Cheynel N. Pneumoretroperitoneum and pneumomediastinum revealing a left colon perforation. Int Surg. 2015; 100:984-988.

- Kuhn G, Lekeufack JB, Chilcott M and Mbaidjol Z. Subcutaneous emphysema caused by an extraperitoneal diverticulum perforation: description of two rare cases and review of the literature. Case Reports Surg. 2018; Article ID 3030869.

- Hunt I, Van Gelderen F and Irwin R. Subcutaneous emphysema of the neck and colonic perforation. Emerg Med J. 2002; 19:465.

- Murariu D, Tatsuno BK, Tom MK, You JS and Maldini G. Subcutaneous emphysema, pneumopericardium, pneumomediastinum and pneumoretroperitoneum secondary to sigmoid perforation: A case report. Hawai J Med Pub Health. 2012; 71:74-77.

- Muronoi T, Kidani A, Hira E, Takeda K, Kuramoto S, Oka K, Shimojo Y and Watanabe H. Mediastinal, retroperitoneal and subcutaneous emphysema due to sigmoid colon penetration; A case report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Reports 2019; 55:213-217.

- Riccardello GJ, Barr LK and Bassani L. Bowel perforation presenting with acute abdominal pain and subcutaneous emphysema in a 14 year old girl with an abandoned distal peritoneal shunt catheter: case report. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2016; 18:325-328.

- Diop S, Giabicani M and Legriel S. Colonic perforation revealed by massive subcutaneous emphysema. Int J Crit Ill Inj Sci. 2021; 11:106-108.

- Mirzayan R, Cepkinian V, Asensio JA. Subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, pneumopericardium and pneumoperitoneum from rectal barotrauma. J Trauma. 1996;6:1073 5.

- Lee YJ, Basu NN, Parampili U and Birch D. An unusual case of rectal perforation resulting in extensive surgical emphysema. BMJ Case Reports. 2012; 10.1136/bcr.09.2011.4822.

- Besic N, Zgajnar J, Kocijancic I. Pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium, and pneumoperitoneum caused by peridiverticulitis of the colon: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004; 47:766-768.

- Asano TK, Burns A, Pinchuk B and Shargall Y. Surgical images: An unusual presentation of perforated sigmoid colon. J Can Chir. 2008; 51: 474-475.

- Choudhury M and Vassallo M. Cervical subcutaneous emphysema; sequelae from occult perforation of sigmoid diverticulum. Int J Clin Med. 2010; 78-80.

- Siddiqui UT, Shahzad H and Raja AJ. Pneumoperitoneum, pneumoretroperitoneum, pneumomediastinum and extensive subcutaneous emphysema in a patient with ulcerative colitis: A case report. Int J Surg Case Reports. 2015; 17:12-15.

- Sahu SK, Bisht M and Sachan PK. Appendicular abscess leading to surgical emphysema of abdominal wall and thigh: A case report. J Surg Arts. 2011; 4:15-17.

- Falconi S, Wilhelm C, Loewen J and Soliman B. Necrotizing fasciitis of the abdominal wall secondary to complicated appendicitis: A case report. Cureus. 2023; 15:e39635.

- Ho HC, Burchell S, Morris P and Yu M. Colon perforation, bilateral pneumothoraces, pneumopericardium, pneumomediastinum, and subcutaneous emphysema complicating endoscopic polypectomy: anatomic and management considerations. Am Surg. 1996; 62:770-774.

- Marwan K, Farmer KC, Varley C and Chapple KS. Pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, pneumoperitoneum, pneumoretroperitoneum and subcutaneous emphysema following diagnostic colonoscopy. AnnRCollSurgEngl. 2007; 89:W20-W21.

- Chan YC, Tsai YC and Fang SY. Subcutaneous emphysema, pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, and pneumoperitoneum during colonoscopic balloon dilatation: A case report. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2010; 26:669-672.

- Jung HC, Kim HJ, Ji SB, Cho JH, Kwak JH, Lee CM, Kim WS, Kim JJ, Lee JM and Lee SS. Pneumoperitoneum, pneumomediastinum, subcutaneous emphysema after a rectal endoscopic mucosal resection. Ann Coloproctol. 2016;32:234-238.

- Bouma G, van Bodegraven AA, van Waesberghe JH, Mulder CJ and Pieters-van den Bos IC. Post-colonoscopy massive air leakage with full body involvement: An impressive complication with uneventful recovery. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009; 104: 1330-1332.

- Falidas E, Anyfantakis G, Vlachos K, Goudeli C, Stavros B and Villias C. Pneumoperitoneum, retropneumoperitoneum, pneumomediastinum and diffuse subcutaneous emphysema following diagnostic colonoscopy. Case Reports Surg. 2012; 10.1155/2012/108791.

- Lu A and Aronowitz P. Sigmoid perforation in association with colonoscopy. NEJM. 2012; 366:744.

- Dehal A and Tessier DJ. Intraperitoneal and extraperitoneal colonic perforation following diagnostic colonoscopy. J Soc Laparoendosc Surg. 2014; 18: 136-141.

- Khan M, Ijaz M, Bukhari S, Dirweesh A and Christmas D. Post-colonoscopy colonic perforation presenting with subcutaneous emphysema: A case report. Gastroenterol Res. 2017;10:135-137.

- Jaafar S, Fong SSH, Waheed A, Misra S and Chavda K. Pneumoperitoneum with subcutaneous emphysema after a post colonoscopy colonic perforation. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2019; 58: 117-120.

- Yang CH, Su FI, Lin CY, Liu YW and Sheen-Chen SM. Facial subcutaneous emphysema as a rare manifestation of complications after endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008; 67:377-378.

- Beintaris I, Polymeros D, Papanikolaou IS, Kontopoulou C, Kourikou A, Sioulas AD, Danias N, Dimitriadis G and Triantafyllou K. Fatal perforation with subcutaneous emphysema complicating ERCP. Endoscopy. 2012; 44:E313-E314.

- Ferrara F, Luigiano C, Billi P, Jovine E, Cinquantini F and N. Pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, pneumoperitoneum, and subcutaneous emphysema after ERCP. Gastrointest Endoscopy. 2009; 69:1398-1401.

- Feret-Adrabinska W, Wojciechowski J, Skolozdrzy T, Daniel A, Gawel K and Bialek A. Subcutaneous emphysema of the lower extremity and pneumoperitoneum after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-related duodenal perforation. Pol Arch Int Med. 2023; 133:16568.

- Nadeem A, Husnain A, Zia MT and Ahmed A. Concurrent acute pancreatitis, pneumoperitoneum, and pneumomediastinum following ERCP-related perforation: A rare and insightful case study. Radiol Case Reports 2024; 19:1419-1423.

- Tridente A, Clarke GM, Walden A, McKechnie S, Hutton P, Mills GH, Gordon AC, Holloway PAH, Chiche JD, Bion J, Stuber F, Garrard C, Hinds C and the GenOSept Investigators. Patients with faecal peritonitis admitted to European intensive care units: an epidemiological survey of the GenOSept cohort. Intensive Care Med. 2014; 40:202-210.

- Hsu CW, Sun SF. Iatrogenic pneumothorax related to mechanical ventilation. World J Crit Care Med. 2014; 3:8-14.