Preeclampsia Insights: Salt-Loaded Rat Model Study

Bridging Models: Preeclampsia Biomarkers in Salt-Loaded Rats and Human Patients

Deliana Rojas1, Cilia Abad2, Teresa Proverbio1, Sandy Piñero1, Margrego Piña1, Fulgencio Proverbio1, Reinaldo Marín1*

- Center for Biophysics and Biochemistry (CBB), Venezuelan Institute for Scientific Research (IVIC), AP 21827, Caracas 1020A, Venezuela

- Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Faculty of Pharmacy in Hradec Kralove, Charles University, Akademika Heyrovskeho 1203, Hradec Kralove 500 05, Czech

Corresponding: [email protected]

In memoriam

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 January 2025

CITATION: ROJASA, Deliana et al. Bridging Models: Preeclampsia Biomarkers in Salt-Loaded Rats and Human Patients. Medical Research Archives,.Available at: <https://esmed.org/MRA/mra/article/view/6233>.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i1.6233

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

Preeclampsia, a pregnancy-specific syndrome with multisystem involvement, significantly contributes to maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. This study compared physiological, fetal, and placental parameters between preeclamptic women and salt-loaded pregnant rats, an established animal model for preeclampsia. We evaluated lipid peroxidation levels in both placental homogenates and red blood cell ghosts, and Ca-ATPase activity in placental homogenates. Additionally, we assessed the effects of magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) treatment on these parameters. Salt-loaded pregnant rats received 1.8% NaCl solution ad libitum for seven days starting from the 15th day of pregnancy. For analysis, blood and placental samples were obtained from preeclamptic women and the rat model. Results showed that salt-loaded pregnant rats exhibited similar characteristics to preeclamptic women, including increased lipid peroxidation, and lowered Ca-ATPase activity in placental and red blood cell ghosts. MgSO4 treatment in preeclamptic women and salt-loaded rats modified Ca-ATPase activity and lipid peroxidation levels in red blood cell membranes and placental membranes, bringing values closer to normal values. The reduction in lipid peroxidation by MgSO4 may account for increased Ca-ATPase activity. This study validates the salt-loaded pregnant rat model as a valuable tool for investigating preeclampsia, offering insights into the condition’s pathophysiology and potential therapeutic interventions.

Keywords

Preeclampsia, Lipid peroxidation, Ca-ATPase, Animal Model, Magnesium Sulfate.

Introduction

Preeclampsia, a complex pregnancy-specific disorder affecting 5-8% of pregnancies worldwide, remains a leading cause of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. Characterized by new-onset hypertension (systolic blood pressure >140 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure >90 mmHg) accompanied by proteinuria, other maternal organ dysfunctions (including liver, kidney, neurological), hematological involvement, or uteroplacental dysfunction (such as fetal growth restriction or abnormal Doppler ultrasound findings of uteroplacental blood flow), preeclampsia’s underlying pathophysiology remains incompletely understood.

Animal models, including the salt-loaded pregnant rat, have proven invaluable in understanding the complexities of preeclampsia. The model of salt-loaded pregnant rat, induced by administering a 1.8% NaCl solution to pregnant rats starting from day 15 of gestation, recapitulates key features of human preeclampsia, including hypertension, proteinuria, oxidative stress, reduced uteroplacental perfusion, and altered placental function.

The similarities between salt-loaded rats and preeclamptic women extend beyond clinical manifestations. Both exhibit increased oxidative stress markers, compromised antioxidant defenses, and altered membrane transport systems. Notably, both demonstrate disrupted calcium homeostasis, reflected in reduced Ca-ATPase activity in placental tissue and red blood cells. Furthermore, parallel changes in red blood cell osmotic fragility and lipid peroxidation levels underscore the model’s relevance.

Magnesium sulfate (MgSO4), a standard treatment for preventing eclamptic seizures, has demonstrated remarkable antioxidant properties in preeclamptic women. However, the therapeutic response to MgSO4 in salt-loaded rats has not yet been evaluated, an investigation that could validate this animal model of preeclampsia. This therapeutic agent reduces lipid peroxidation, enhances antioxidant enzyme activities, and improves membrane stability. In placental tissue and red blood cells, MgSO4 treatment significantly decreases oxidative stress markers and restores Ca-ATPase activity to levels comparable to normotensive pregnancies. The antioxidant effects of MgSO4 appear to be mediated through multiple mechanisms, including direct free radical scavenging and modulation of cellular redox pathways.

By understanding the similarities and differences between the salt-loaded rat model and human preeclampsia, researchers can develop and evaluate novel therapeutic strategies to combat this significant health challenge. This comparison provides valuable insights into potential therapeutic targets for preeclampsia management, particularly those focusing on oxidative stress pathways.

Materials and Methods

PATIENTS

Pregnant women, either normotensive or preeclamptic, from the Maternity Hospital ‘Concepción Palacios’ in Caracas. All normotensive and preeclamptic pregnant women enrolled in the study were nulliparous, and all of them gave birth by vaginal delivery. The normotensive pregnant women had no history of hypertension and no evidence of hypertension or proteinuria during their current pregnancy. The preeclamptic pregnant women were identified by new onset of hypertension (140/90 mm Hg) or a rise of 30 mm Hg in systolic pressure or of 15 mm Hg in diastolic pressure (measured twice 6 h apart at bed rest) after 20 weeks of pregnancy. The condition was confirmed by the presence of one or more other features: proteinuria, other maternal organ dysfunction (including liver, kidney, neurological), or hematological involvement, and abnormal Doppler ultrasound findings of uteroplacental blood flow. Any patient who, according to her medical history, was under medical treatment to control blood pressure, or was taking >1 g of elemental calcium per day during pregnancy, or had a history of chronic hypertension, diabetes, calcium metabolism disorders, or any other chronic medical illness, was not considered for this study.

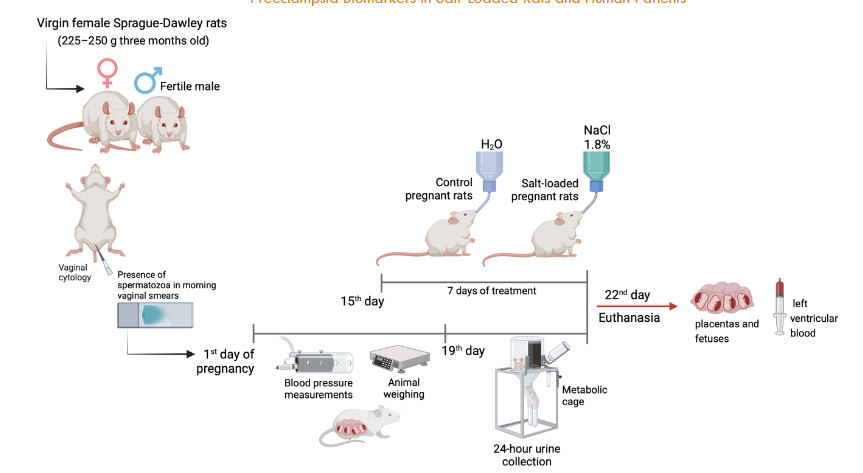

ANIMALS

The experiments were performed on female Sprague-Dawley rats (weighing 225–250 g, three months old). The animals were housed, four animals per cage, with constant room temperature (23 ± 1 °C, mean ± SD), low noise, and the following light–darkness schedule: 12 h of light (06:00–18:00 h, 80 lux) and 12 h of darkness (18:00–06:00 h). All the rats received food and water ad libitum. Virgin female rats in the proestrus phase of their estrous cycle (determined through daily cytological assessment) were paired with a proven fertile male in a controlled animal facility. Day 1 of pregnancy was established when spermatozoa were found in morning vaginal smears. Control pregnant rats had tap water during the whole treatment period. The salt-loaded pregnant rats received 1.8% NaCl solution ad libitum as a beverage for seven days, starting on the 15th day of pregnancy. The rats were weighed during the pregnancy. In addition, the blood pressure of both groups was routinely measured by the indirect tail-cuff method (IITC Life Science equipment, MRBP System) from the first week of pregnancy to the 19th day of pregnancy. On the 19th day of pregnancy, the rats were housed in a metabolic cage until the treatment’s end (22nd day of pregnancy). The urine of the last 24 h is recollected, centrifuged to 16000x g during 10 min, and diluted 10X before protein determination. At the end of the treatment (21st day of pregnancy), the rats were i.p. anesthetized with thiopental and euthanized to register fetal parameters. Immediately, 10 ml of blood was drawn from the left ventricle utilizing heparinized syringes, and then, the placentas and fetuses were removed.

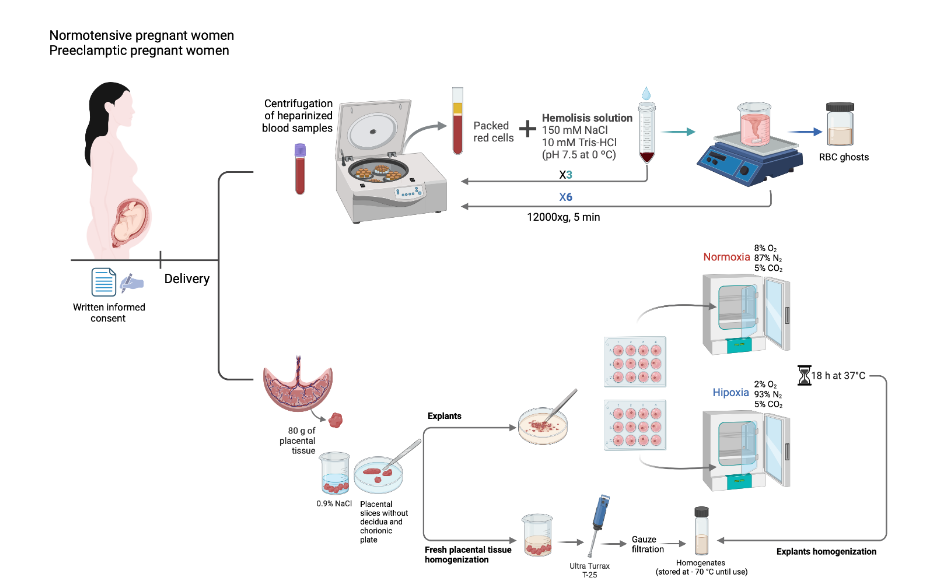

PREPARATION AND HOMOGENIZATION OF HUMAN PLACENTA

Once obtained, the placenta was immediately transported to the laboratory and processed within 30 min. The placenta was kept at 4 °C at all times. Approximately 80 g of placental tissue were obtained from central portions of each placenta after removing the cord, amniochorion, chorionic plate, and a 0.25 cm-thick slice from the decidual surface. The tissue was cut into 1 x 1 cm pieces and washed with a saline solution (0.9% NaCl) to remove blood. The tissue was then homogenized in an Ultra Turrax T-25 dispersing apparatus with a dispersing tool with an S25N blade at 24,000 rpm for 1 min in a solution (3 ml/g) containing: 250 mM sucrose, 10 mM Tris-Hepes (pH 7.2), 5 mM EGTA, 5 mM EDTA, and 1 mM PMSF. The homogenates were filtered through gauze filters and stored in the freezer at -70 °C until use, for no longer than seven days.

EXPLANT CULTURE OF HUMAN PLACENTA

After removing the chorionic plate and about 0.25 cm of decidua, explants were prepared using only tissue from the intermediate region of the placenta. In brief, randomly sampled villous tissue fragments, of roughly 0.5 cm × 0.5 cm, were cleaned of large vessels and blood clots, rinsed 5 times in cold sterile saline, placed in 12-well plates (Nunclon TM Surface) containing 2 mL of DMEM-F12 medium and 10% fetal calf serum as culture medium, and enriched by the addition of crystalline penicillin 100,000 UI/mL, gentamicin 48 µg/mL, and amphotericin B 3 µg/mL. The preparation of placental explants was carried out on ice at 4 ºC and completed in approximately 30 min. Without further incubations, the explants prepared in this way were identified as freshly prepared placental explants. The tissue explants were incubated for 4 h at 37 ºC in 4 mL medium (DMEM-F12 with 10% FCS) in a sterile CO2 incubator (Shel Lab Model IR2424) with a gas mixture composed of 8% O2/87% N2/5% CO2 (normoxia), with constant gas pressure. The culture medium was then removed and replaced with a new culture medium. The explants were divided into two groups: one group was kept under normoxia for 18 h at 37 ºC and the other group was cultured under hypoxia (2% O2/93% N2/5% CO2) for 18 h at 37 °C. At the end of the culture period, the explants were carefully removed and rinsed 5 times in cold sterile saline. The explants were then used for the homogenization as previously explained.

PREPARATION AND HOMOGENIZATION OF THE RAT PLACENTAL TISSUE

The placentas, without the umbilical cord, were washed with a saline solution at 4 ºC. After weighing and cleaning, the amniochorion and the chorionic plate were removed, and the placentas were cut into small pieces and homogenized at 4 ºC in a solution containing 50 mM Tris-Hepes, pH 7.2; 5 mM EGTA; 5 mM EDTA; 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and 250 mM sucrose (buffer 1) to samples to assay Ca-ATPase. TBARS samples were homogenized similarly but the solution contained 5 mM dibasic phosphate (Na2HPO4) (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM PMSF (phosphate buffer with PMSF). The homogenates were filtered through gauze filters and stored in the freezer at -70 ºC until use, for no longer than seven days.

RED BLOOD CELL GHOSTS

Heparinized blood samples were centrifuged at 12000xg, 5 min, and 4 ºC. The plasma was saved, the buffy coat was discarded, and the packed red cells were washed three times by centrifugation under the same conditions, in a solution containing 150 mM NaCl and 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5 at 0 ºC). The washed erythrocytes were then utilized to prepare hemoglobin-free red blood cell ghosts, according to the method of Heinz and Hoffman. The red blood cell ghosts were stored in a solution containing 17 mM Tris-HCl and 0.1 mM EDTA (pH 7.5 at 0 ºC) and kept frozen at -70 ºC until use.

Ca-ATPase ACTIVITY

The Ca-ATPase activity of placental homogenates was determined by a modified method described elsewhere. The quantity of inorganic phosphate liberated from the hydrolysis of ATP was determined as previously described. The assay was carried out in the presence of 1 mM thapsigargin, with and without 7.56 μM free Ca2+. The Ca-ATPase activity is expressed as nmol Pi/mg protein min, after subtraction of a blank run in parallel under the same conditions. The protein concentration, in all the cases, was determined according to the method of Bradford. The thapsigargin-insensitive Ca-ATPase activity was calculated as the difference in the phosphate liberated in a medium containing Mg2++Ca2+ minus the one liberated in the same medium but in the absence of Ca2+. To avoid the presence of membrane vesicles, the different fractions were always pretreated before the assays with SDS, as previously described, at a ratio of 1.25 SDS/protein. The ATPase activity of the red cell ghosts was similarly determined by measuring the quantity of inorganic phosphate liberated from the hydrolysis of ATP, following the method described by Nardulli et al. with minor modifications. The liberated inorganic phosphorus was determined in an ELISA (Tecan, San Jose, CA – Sunrise) spectrophotometer at 705 nm, following the Fiske–Subbarow method. In all cases, the Ca-ATPase activity was calculated by paired data.

TBARS ASSAY

The amount of lipid peroxidation of the red cell ghosts and placental homogenates was estimated by measuring the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) following a method described by Feix et al. The absorbance was measured at 532 nm, and the TBARS values were calculated using malondialdehyde (MDA) standard curve, prepared by acid hydrolysis of 1,1,3,3-tetramethoxypropane. The values were expressed as nmoles of MDA per milligram of protein.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

One-way ANOVA assessed comparisons between treatment conditions with the post hoc analysis with the Student–Newman–Keuls test. The Student’s t-test performed statistical analysis between two conditions. All results were expressed as means ± SE, and n represents the number of experiments performed with different preparations. A p-value of 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

Results

The study presents comprehensive findings on the biochemical changes associated with preeclampsia and the potential therapeutic effects of magnesium sulfate (MgSO4). The initial comparison between preeclamptic and normotensive pregnant women revealed significant differences in blood pressure and protein excretion. Preeclamptic women exhibited substantially higher systolic and diastolic blood pressures, as well as increased protein excretion (Table 1). This clinical presentation of the preeclamptic women was successfully mirrored in a salt-loaded pregnant rat model, where similar elevations in blood pressure and protein excretion were observed, validating its use for further experimental studies.

| Parameter | Normotensives (at delivery) | Preeclamptics (at delivery) | Control pregnant rats (day 19) | Salt-loaded pregnant rats (day 19) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 114.8 ± 4.7† | 151.4 ± 5.1†* | 102.9 ± 2.5 | 122.0 ± 2.2* |

| Diastolic blood pressure at (mmHg) | 67.9 ± 3.8† | 91.1 ± 2.5†* | 65.1 ± 1.7 | 78.8 ± 2.5* |

| Mean blood pressure (mmHg) | 83.5 ± 4.0† | 111.2 ± 3.4† | 77.7 ± 1.9 | 93.2 ± 2.3* |

| Protein excretion (mg/24h) | 122 ± 72† | 402 ±96†** | 5.97 ± 0.65 | 11.92 ± 0.88* |

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=16 for pregnant women, n=7 for control rats, n=10 for salt-loaded pregnant rats in arterial pressure measurements, and n=8 for pregnant rats in protein excretion measurements). Data taken from Abad et al. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2015, 34:65-79. *p<0.001 versus normotensives or control pregnant rats. **p<0.05 versus normotensives or control pregnant rats.

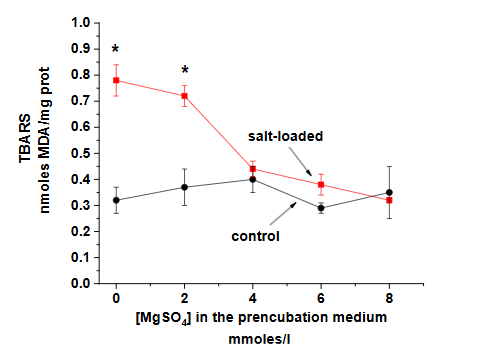

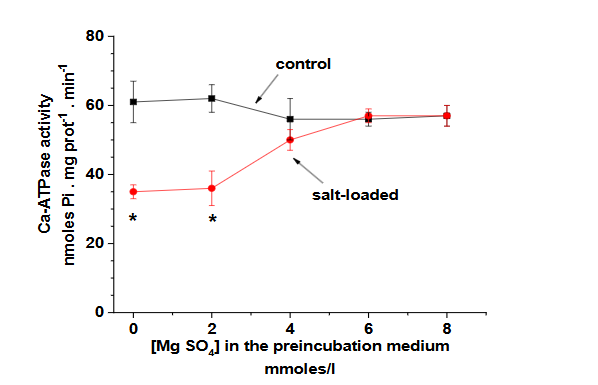

A key finding was the increased oxidative stress in preeclampsia, as evidenced by elevated lipid peroxidation levels (TBARS) in both placental tissue and red blood cells (Table 2). Preeclamptic women showed nearly double the TBARS levels compared to normotensive women in both tissues. Similarly, salt-loaded pregnant rats exhibited a 2.9-fold increase in TBARS levels in placental tissue and a 1.6-fold increase in red blood cells compared to control rats, indicating comparable oxidative stress patterns. This increased oxidative stress was accompanied by a significant reduction in Ca-ATPase activity, in both preeclamptic women and salt-loaded pregnant rats, suggesting a potential mechanism linking oxidative damage to calcium homeostasis disruption in preeclampsia.

| Parameter | Normotensives | Preeclamptics | Control pregnant rats (day 19) | Salt-loaded pregnant rats (day 19) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBARS Placenta | 0.34 ± 0.04† (n=11) | 0.69 ± 0.05† (n=11) | 0.27 ± 0.03 (n=19) | 0.78 ± 0.11 (n= 16) |

| TBARS Red Blood Ghosts | 0.41 ± 0.03†† (n=11) | 0.87 ± 0.07*†† (n=11) | 0.52 ± 0.14 (n=13) | 0.83 ± 0.14 (n= 6) |

| Ca-ATPase Placenta | 30 ± 2 (n=11) | 13 ± 1 (n=11) | 32 ± 3 (n=8) | 18 ± 1 (n=6) |

| Ca-ATPase Red Blood Ghosts | 19.88 ± 1.02†† (n=11) | 9.58 ± 0.44†† (n=11) | 25 ± 1 (n=7) | 12 ± 2 (n=7) |

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. Data taken from Carrera et al. (2003) Hypertens. Pregnancy. 22:295-304. TBARS are expressed as nmoles malondialdehyde . mg prot-1. ATPase activity is expressed as nmoles Pi.mg prot-1 . min-1.

The detailed characterization of Ca-ATPase revealed interesting insights into its behavior in preeclamptic conditions and salt-loaded pregnant rats (Table 3). While the enzyme’s affinity for calcium (Km) remained unchanged between normotensive and preeclamptic samples, its maximum activity (Vmax) was significantly reduced in preeclamptic conditions and salt-loaded pregnant rats. This suggests that the enzyme’s basic structure and calcium-binding properties remain intact, but its overall function is compromised, possibly due to oxidative damage.

| Parameter | Normotensive | Preeclamptic | Control pregnant rats (day 19) | Salt-loaded pregnant rats (day 19) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km for calcium | 0.25 ± 0.02 (n=11) | 0.25 ± 0.02 (n=11) | 0.15 ± 0.01 (n=8) | 0.146 ±0.01 (n=6) |

| Vmax | 49 ±3 (n=11) | 23 ± 2 (n=11) | 67 ± 2.76 (n=8) | 37 ±1.44 (n=6) |

| Optimal pH | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.4 |

| Optimal temperature | 45 | 45 | 37 | 37 |

µmoles Ca2+; ATPase activity is expressed as nmoles Pi.mg prot-1 . min-1; ºC.

The study’s most promising findings came from investigating MgSO4 treatment (Table 4). When preeclamptic women received MgSO4 treatment, their TBARS levels decreased, and Ca-ATPase activity improved significantly. These beneficial effects were also demonstrated in vitro (Table 5), where preincubation of red blood cells from preeclamptic women with MgSO4 showed similar improvements. This suggests that MgSO4’s therapeutic action may work through multiple mechanisms associated with the plasma membrane, including protection against oxidative stress and restoration of calcium handling capabilities. This study also explored the role of hypoxia, a condition often associated with preeclampsia (Table 6). Under hypoxic conditions, placental tissue showed increased oxidative stress and decreased Ca-ATPase activity. Notably, the addition of MgSO4 protected against these hypoxia-induced changes, restoring both parameters to near-normal levels. This protective effect against hypoxia-induced damage represents another potential mechanism through which MgSO4 might exert its therapeutic benefits in preeclampsia.

| Preeclamptic patients | TBARS | Ca-ATPase activity |

|---|---|---|

| Before treatment with MgSO4 | 0.87 ± 0.07 | 9.58 ± 0.44 |

| After treatment with MgSO4 | 0.45 ± 0.09* | 20.38 ± 1.15* |

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM of determinations with 11 different preparations for each case. TBARS are expressed as nmoles malondialdehyde. mg prot-1. ATPase activity is expressed as nmoles Pi.mg prot-1. min-1; *p<0.001.

| Preincubation | Normotensive patients | Preeclamptics patients |

|---|---|---|

| 4 mM NaCl | 0.39 ± 0.08 | 0.88 ±0.11 |

| 4 mM MgSO4 | 0.31 ± 0.12 | 0.47 ± 0.05** |

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM of determinations carried out with preparations from different women (n = 11 in each case). TBARS are expressed as nmoles malondialdehyde. mg prot-1. ATPase activity is expressed as nmoles Pi.mg prot-1 . min-1; *p<0.001 vs no preincubation; **p<0.05 vs no preincubation.

| Condition | TBARS | Ca-ATPase |

|---|---|---|

| Fresh | 9.3 ± 0.33 | 34 ± 3 |

| Normoxia | 11.6 ± 0.73 | 30 ± 1 |

| Hypoxia | 15.3 ± 0.53* | 13 ± 1** |

| Hypoxia + 2 mM MgSO4 | 11.34± 0.78 | 33 ±3 |

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=4) per group. TBARS are expressed as nmoles malondialdehyde. mg prot-1. ATPase activity is expressed as nmoles Pi.mg prot-1 . min-1; *p< 0.01 vs all conditions; **p<0.001 vs all conditions.

The parallel studies in the salt-loaded rat model provided additional support for these findings. The animal model not only reproduced the biochemical changes seen in human preeclampsia but also showed similar responses to MgSO4 treatment, as demonstrated by the effects on lipid peroxidation levels (Figure 3) and Ca-ATPase activity (Figure 4).

This consistency between human and animal studies strengthens the validity of the findings and provides a valuable platform for further investigation of therapeutic interventions.

Discussion

The present study provides compelling evidence validating the salt-loaded pregnant rat as a valuable model for investigating preeclampsia, particularly regarding oxidative stress and calcium homeostasis disruption. Our findings demonstrate remarkable parallels between biochemical alterations in preeclamptic women and salt-loaded pregnant rats, specifically in lipid peroxidation levels and active calcium transport mechanisms.

A consistent pattern of increased oxidative stress, measured by TBARS levels, was observed in both placental tissue and red blood cells of preeclamptic women and salt-loaded rats. This elevated oxidative stress was accompanied by significant reductions in Ca-ATPase activity, suggesting a mechanistic link between oxidative damage and disrupted calcium homeostasis. The preservation of enzyme affinity (Km) for calcium, despite reduced maximum activity (Vmax), indicates that oxidative stress likely affects the enzyme’s functional capacity without altering its fundamental calcium-binding properties.

The study revealed new insights into the mechanism of action of MgSO4 in preeclampsia treatment. MgSO4 not only protects against oxidative stress but also modulates endothelial function and inflammatory responses, mitigating endothelial damage and reducing inflammatory cytokines at the maternal-fetal interface. These findings provide a molecular basis for MgSO4’s well-documented clinical efficacy in preventing eclamptic seizures.

Our investigation of hypoxic conditions provided additional mechanistic insights into preeclampsia pathophysiology. The observed protective effects of MgSO4 against hypoxia-induced oxidative stress and Ca-ATPase dysfunction suggest that this treatment may be particularly beneficial in cases where placental hypoxia is a prominent feature. This protection against hypoxia-induced damage represents a previously unrecognized mechanism through which MgSO4 may exert its therapeutic benefits.

The consistency of biochemical changes and therapeutic responses between human samples and our rat model strengthens the validity of using salt-loaded pregnant rats in preeclampsia research. This model not only reproduces the clinical manifestations of preeclampsia but also mirrors the underlying molecular alterations and therapeutic responses, making it an invaluable tool for testing novel therapeutic interventions and investigating disease mechanisms.

Our findings have important clinical implications, despite the inherent limitations of using an animal model to predict human responses. The demonstrated relationship between oxidative stress and calcium transport dysfunction suggests that antioxidant therapies, particularly those targeting membrane systems, might be beneficial in preeclampsia management. Furthermore, the protective effects of MgSO4 against both oxidative stress and hypoxia-induced damage provide a stronger rationale for its use in preeclampsia treatment and suggest potential benefits of earlier intervention in high-risk cases. Moreover, recent reviews underscore that MgSO4’s clinical benefits extend beyond seizure prevention, encompassing reductions in vascular endothelial damage and maternal morbidity, even in cases without neurological symptoms.

Future research directions emerging from this study include the need to investigate the detailed molecular mechanisms through which MgSO4 provides membrane protection and modulates calcium homeostasis. Additionally, the validated animal model can be utilized to explore novel therapeutic approaches targeting the oxidative stress-calcium homeostasis axis in preeclampsia. Long-term studies are also warranted to evaluate the potential developmental consequences of these biochemical alterations and the protective effects of MgSO4 on fetal outcomes.

This study significantly advances our understanding of preeclampsia pathophysiology and validates the salt-loaded pregnant rat model for future research in this critical area of maternal health. The insights gained from this investigation not only elucidate the complex interplay between oxidative stress, calcium homeostasis, and hypoxia in preeclampsia but also provide scientific evidence for developing more targeted and effective therapeutic strategies.

Conclusion

Our results collectively suggest that MgSO4’s therapeutic benefits in preeclampsia may be mediated through its ability to reduce oxidative stress and restore calcium homeostasis. The consistency of these effects across different experimental conditions and models, along with the demonstrated protection against hypoxia-induced damage, provides strong support for its continued use in preeclampsia treatment. Furthermore, these findings open new avenues for understanding the pathophysiology of preeclampsia and the development of targeted treatments.

Author Contributions

DR, CA, FP, and RM designed the experiments and wrote the paper. DR, CA, TP, SP, and MP performed the experiments. DR, CA, FP, and RM analyzed the data. DR, CA, and RM revised the final paper. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declarations

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICAL APPROVAL: The study with pregnant women was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Maternity Concepción Palacios and by the Bioethics Committee of IVIC, and all women gave their informed signed consent. All experimental procedures with pregnant rats were approved and performed in compliance with the local animal ethics committee (Cobianim/IVIC).

References

- Sibai B, Dekker G, Kupferminc M. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2005;365(9461):785-799.

- ACOG. Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia: ACOG practice bulletin summary, number 222. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(6):1492-1495.

- Chappell LC, Cluver CA, Kingdom J, Tong S. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2021;398(10297):341-354.

- Arany Z, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Karumanchi SA. Animal Models of Cardiovascular Complications of Pregnancy. Circ Res. 2022;130(12):1763-1779.

- Bakrania BA, George EM, Granger JP. Animal models of preeclampsia: investigating pathophysiology and therapeutic targets. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020.

- Beauséjour A, Auger K, St-Louis J, Brochu M. High-sodium intake prevents pregnancy-induced decrease of blood pressure in the rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285(1):H375-383.

- Beauséjour A, Bibeau K, Lavoie JC, St-Louis J, Brochu M. Placental oxidative stress in a rat model of preeclampsia. Placenta. 2007;28(1):52-58.

- Beauséjour A, Houde V, Bibeau K, Gaudet R, St-Louis J, Brochu M. Renal and cardiac oxidative/nitrosative stress in salt-loaded pregnant rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293(4):R1657-1665.

- Sakowicz A, Bralewska M, Kamola P, Pietrucha T. Reliability of Rodent and Rabbit Models in Preeclampsia Research. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(22).

- Rojas D, Rodríguez F, Barraez J, et al. Osmotic fragility of red blood cells, lipid peroxidation and Ca2+-ATPase activity of placental homogenates and red blood cell ghosts in salt-loaded pregnant rats. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29(2):229-233.

- Abad C, Proverbio T, Piñero S, et al. Preeclampsia, Placenta, Oxidative Stress, and PMCA. Hypertension Preg. 2012;31(4):427-441.

- Abad C, Teppa-Garrán A, Proverbio T, Piñero S, Proverbio F, Marín R. Effect of magnesium sulfate on the calcium-stimulated adenosine triphosphatase activity and lipid peroxidation of red blood cell membranes from preeclamptic women. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;70(11):1634-1641.

- Abad C, Vargas FR, Zoltan T, et al. Magnesium sulfate affords protection against oxidative damage during severe preeclampsia. Placenta. 2015;36(2):179-185.

- Chiarello DI, Marín R, Proverbio F, et al. Mechanisms of the effect of magnesium salts in preeclampsia. Placenta. 2018;69:134-139.

- Marín R, Abad C, Rojas D, et al. Magnesium salts in pregnancy. JTEMIN. 2023;4:100071.

- Abad C, Chiarello DI, Rojas D, Beretta V, Perrone S, Marín R. Oxidative Stress in Preeclampsia and Preterm Newborn. In: Andreescu S, Henkel R, Khelfi A, eds. Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress: Clinical Aspects of Oxidative Stress. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland; 2024:197-220.

- Fernández M, Marín R, Proverbio F, Chiarello DI, Ruette F. Magnesium sulfate against oxidative damage of membrane lipids: A theoretical model. Int J Quantum Chem, e25423. 2017(e25423).

- Fernández M, Marín R, Proverbio F, Ruette F. Effect of magnesium sulfate in oxidized lipid bilayers properties by using molecular dynamics. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2021;26:100998.

- Fernández M, Marín R, Ruette F. Antioxidant Activity of MgSO4 Ion Pairs by Spin-Electron Stabilization of Hydroxyl Radicals through DFT Calculations: Biological Relevance. ACS Omega. 2024;9(34):36640-36647.

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Analyt Biochem. 1976;72:248-254.

- Heinz E, Hoffman JF. Phosphate incorporation of Na+,K+ ATPase activity in human red blood cell ghost. J Cell Comp Physiol. 1965;54:31-44.

- Marín R, Proverbio T, Proverbio F. Inside-out basolateral plasma membrane vesicles from rat kidney proximal tubular cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;858(1):195-201.

- Proverbio F, Proverbio T, Marin R. Na+-ATPase is a different entity from the (Na++K+)-ATPase in rat kidney basolateral plasma membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;858(1):202-205.

- Nardulli G, Proverbio F, Limongi FG, Marín R, Proverbio T. Preeclampsia and calcium adenosine triphosphatase activity of red blood cell ghosts. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:1361-1365.

- Fiske CH, Subbarow Y. The colorimetric determination of phosphorus. J Biol Chem. 1925;66:375-400.

- Feix JB, Bachowski GJ, Girotti AW. Photodynamic action of merocyanine 540 on erythrocyte membranes: structural perturbation of lipid and protein constituents. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1075(1):28-35.

- Abad C, Carrasco M, Piñero S, et al. Effect of magnesium sulfate on the osmotic fragility and lipid peroxidation of intact red blood cells from pregnant women with severe preeclampsia. Hypertension Preg. 2010;29(1):38-53.

- Marín R, Abad C, Rojas D, Chiarello DI, Teppa-Garrán A. Biomarkers of oxidative stress and reproductive complications. Adv Clin Chem. 2023;113:157-233.