Chronic Migraine and Brain Aging: Hippocampal Atrophy Insights

Chronic Migraine and Accelerated Brain Ageing: A Focus on Hippocampal Atrophy

Dr. Arbind Kumar Choudhary1,

- Department of Physiology, All India Institute of Medical Science, Raebareli, Uttar Pradesh, India

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 July 2025

CITATION:CHOUDHARY, Dr. Arbind Kumar. Chronic Migraine and Accelerated Brain Ageing: A Focus on Hippocampal Atrophy. Medical Research Archives, [S.l.], v. 13, n. 7, july 2025. Available at: <https://esmed.org/MRA/mra/article/view/6728>.

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i7.6728

ABSTRACT

Chronic migraine (CM) is increasingly recognized as more than just a recurring headache condition. It involves significant neurobiological changes that suggest accelerated aging of the brain, particularly affecting the hippocampus, which is essential for memory and cognitive functions. This overview examines the key findings linking CM to notable decreases in cortical thickness, increased white matter hyperintensities, and significant hippocampal atrophy. Research utilizing machine learning in neuroimaging has introduced the concept of the Brain Age Gap (BAG). This concept reveals that individuals with CM have an average brain age that is 4.16 years older than their chronological age, indicating premature aging of their neural structures. These structural changes are associated with difficulties in declarative memory, disruptions in memory-encoding processes, and higher rates of depression and anxiety. Factors such as neuroinflammation, ongoing pain signals, and related health conditions such as obesity and hypertension worsen this neurodegenerative trajectory. The growing body of evidence highlights the urgent need for early identification of at-risk individuals, validation of BAG as a potential cognitive health biomarker, and development of targeted interventions to prevent cognitive decline. To confirm these findings, prospective long-term studies are crucial to confirm the patterns of hippocampal atrophy and to establish effective imaging techniques for migraine management.

Keywords: Chronic Migraine, Brain Aging, Hippocampal Atrophy, Neuroimaging, and Cognitive Decline.

1. Introduction

Migraine affects approximately 12% of the global population, with 60% experiencing at least one attack annually. Chronic migraine, defined as headaches lasting over 72 hours or occurring at least 15 days per month for more than three months, is associated with accelerated brain aging, especially in the hippocampus. The hippocampus is crucial for memory and cognitive function. Chronic migraine not only impairs the quality of life but it also increases the risk of memory loss, cognitive decline, and mood disorders. Research indicates that patients with chronic migraines often exhibit reduced hippocampal volume and younger predicted brain age, suggesting early neurodegenerative changes. This review examined the relationship between chronic migraine and hippocampal atrophy by reviewing neuroimaging evidence. This review focuses on evaluating the neurological effects of migraines, identifying underlying neurobiological mechanisms, such as oxidative stress and neuroinflammation, and assessing structural brain changes. As individuals age, cognitive abilities and bodily functions gradually decline, particularly in brain regions such as the frontal and temporal lobes and hippocampus. The Brain Age framework compares brain health by comparing it to a healthy population baseline. When the predicted brain age exceeds the chronological age, referred to as the Brain Age Gap (BAG), it may serve as a biomarker for underlying health issues. Machine learning models can utilize neuroimaging data to predict brain age and identify the signs of accelerated aging. Studies have shown that chronic migraine patients exhibit significant BAGs, with MRI scans revealing structural changes such as cortical thinning and reduced gray matter. These alterations, influenced by genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors, highlight the complex neurobiological nature of chronic migraine. The Brain Age framework not only sheds light on migraine-associated brain aging but also helps differentiate between healthy and impaired brain states, paving the way for targeted interventions and further research.

2. Hippocampal Atrophy in Chronic Migraine

Chronic migraine is a debilitating neurological disorder defined by headaches occurring five or more days per month for over three consecutive months, with at least eight fitting migraine-specific criteria. This condition significantly affects the quality of life and poses a serious global health concern. Chronic migraines increase the risk of cerebrovascular events such as stroke as well as psychiatric issues such as depression and anxiety. Neuroimaging studies have indicated accelerated brain aging in patients with chronic migraine, with limited research on hippocampal atrophy. Evidence shows altered gray matter volume and disrupted functional connectivity, with patients exhibiting a higher prevalence of white matter hyperintensities (WMH). The hippocampus, vital for memory processing, is located in the medial temporal lobes and includes subregions such as the dentate gyrus (DG) and the Cornu Ammonis (CA) fields. It plays a key role in encoding episodic memory by interacting with the neocortex. Studies in animals, especially rats, have revealed its circuitry and how the DG processes incoming signals. Hippocampal volume is often reduced by approximately 15% in chronic migraine patients compared to those with other headache disorders, indicating accelerated aging and its link to chronic pain and neurodegeneration. Structural MRI studies have shown significant volume reductions in the hippocampus and related areas (e.g., the left temporal pole) in patients with chronic migraine. Functional MRIs indicate altered connectivity, including reduced gray matter density in the anterior cingulate cortex, suggesting compensatory changes in neural organization. These findings challenge traditional models and highlight the need for a reevaluation of the roles of various brain regions in chronic migraine. Particular focus on the atrophy of the hippocampus specifically permits an even more detailed investigation of the susceptibility of this part of the brain. Although changes in other brain areas may also be observed, the hippocampus should be considered as an object of study since it gives more insights into how these structures are related to cognitive and affective sequelae of chronic migraine.

3. Cognitive Implications of Hippocampal Atrophy

The hippocampus is essential for episodic memory, spatial navigation, and various cognitive functions. Recent studies have emphasized its role in processing speed, working memory, and executive functions. However, it is vulnerable to age-related shrinkage, particularly in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, contributing to cognitive decline and linked to elevated Alzheimer’s biomarkers, even in cognitively healthy individuals. Accelerated brain aging in older adults is often reflected in a discrepancy between chronological and brain-predicted age, correlating with neurodegenerative conditions. Additionally, hippocampal atrophy affects cognitive performance in children, leading to deficits in verbal memory and contextual learning. Patients with chronic migraine often experience memory and learning impairments due to hippocampal atrophy. They tend to perform poorly in declarative memory tasks because of inefficient mnemonic strategies and altered information encoding. Compensatory reconsolidation mechanisms emerge as a response to initial learning deficits, and differences in cognitive processing are evident when comparing patients with migraine to healthy controls. Chronic migraine presents a significant burden in terms of disability and is often accompanied by psychiatric comorbidities such as mood disorders. This can lead to hippocampal degeneration, emotional dysregulation, and increased vulnerability to psychological issues. Furthermore, altered connectivity between the hippocampus and surrounding brain regions contributes to cognitive and emotional impairments. Migraines, once considered episodic, are now recognized for their potential to become chronic, especially after menopause. Increased pain sensitization and cognitive impairment contribute to this progression. Patients frequently report cognitive deficits and reduced quality of life due to stress, anxiety, and depression. Understanding the progression of migraines from episodic to chronic requires a comprehensive approach that considers headache duration, emotional well-being, and cognitive decline, which is crucial for effective interventions and improving patient outcomes.

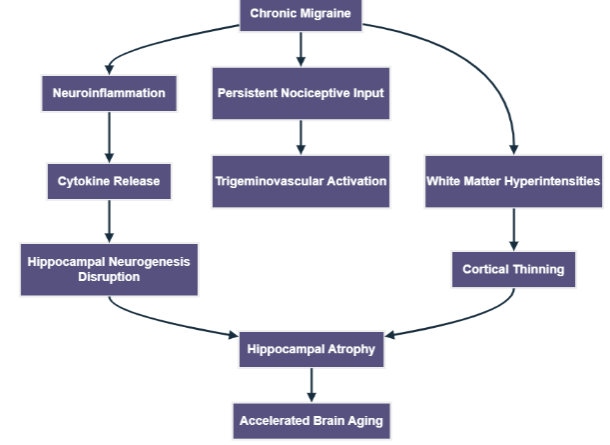

4. Mechanisms Linking Chronic Migraine and Brain Ageing

Accelerated brain aging has emerged as a significant concern, especially with regard to chronic migraine. This condition is linked to reduced cortical thickness and increased brain age, particularly in the frontal, insular, and temporal lobes. Chronic migraines are associated with early signs of microstructural injury and neuroinflammation, which may arise in preclinical stages. Continuous nociceptive input activates trigeminovascular pathways, leading to a cycle of hyperexcitability and discomfort. Additionally, white matter lesions can worsen this dysfunction, further affecting the brain structure and function. The proposed neurobiological pathways connect chronic migraine to accelerated brain aging, highlighting persistent nociceptive signaling, neuroinflammation, and hippocampal degeneration. Chronic migraine is associated with neuroinflammation, alterations in the white matter, and dysfunction of the hippocampus, resulting in cortical thinning and atrophy of the hippocampus, all of which contribute to accelerated aging of the brain. Neuroinflammation plays a critical role in chronic migraines, contributing not only to migraine pathology but also to mechanisms of brain aging. Shared risk factors for other neurodegenerative disorders include depression, anxiety, obesity, and hypertension, which may interact synergistically through neuroinflammation. The association between chronic migraine and hippocampal atrophy complicates this issue because inflammatory mediators may disrupt hippocampal integrity. Evidence suggests that increased brain age and hippocampal atrophy often co-occur, highlighting the need for further research on these interactions. With over one billion people affected by migraines, approximately one-third experience chronic forms, and the implications for brain health are profound.

Neuroimaging studies have revealed that up to 50% of chronic migraine sufferers exhibit white matter hyperintensities compared to less than 20% of those with episodic migraines. Chronic migraine is also linked to a decline in cognitive performance, suggesting that vascular dysregulation may contribute to brain aging. Advanced neuroimaging techniques, especially brain age estimation algorithms, have provided evidence of accelerated brain aging in chronic migraine patients. These tools link higher predicted brain age with poorer neurological outcomes. Recent studies have shown an inverse relationship between hippocampal volume and headache frequency, suggesting that chronic migraine contributes to structural degeneration, particularly in the right hippocampus. Further studies are needed to assess these effects bilaterally and confirm their similarities to neurodegenerative diseases. Morphometric analyses have revealed significant structural changes in the hippocampus of chronic migraine patients compared with those with episodic migraines. While hippocampal atrophy is commonly associated with dementia, its role in primary headache disorders remains underexplored. The entorhinal cortex-hippocampal axis, which is important for memory and mood regulation, may be specially vulnerable to the effects of chronic headaches. Conducting longitudinal studies using serial imaging is essential to understand the long-term impact of chronic migraine on the brain.

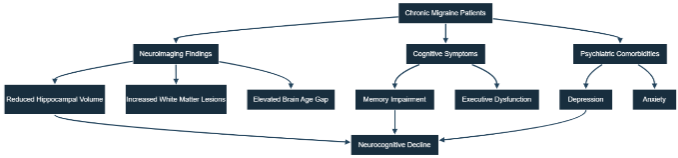

5. Clinical Correlations

Persistent and severe headaches are often associated with thinking difficulties, such as memory problems, trouble concentrating, and task management. The convergence of neuroimaging and clinical findings reinforces the link between hippocampal atrophy and cognitive-psychiatric manifestations in individuals suffering from chronic migraine. Neuroimaging indicates a reduction in hippocampal volume and an increased brain age gap in individuals with chronic migraine, which is associated with cognitive deficits and psychiatric comorbidities, ultimately leading to a decline in neurocognitive function. The clinical, cognitive, and neuroimaging aspects of chronic migraine linked to hippocampal atrophy and brain aging were compiled in Table 1. Studies have shown a direct link between shrinkage of the hippocampus, a part of the brain, and the level of cognitive difficulty. People with significant shrinkage of the hippocampus often have trouble remembering and retrieving memories, indicating that hippocampal shrinkage plays a role in the decline of thinking abilities in individuals with severe and frequent headache. Moreover, research has found that the frequency and duration of headaches are directly related to shrinkage of the hippocampus, demonstrating the long-term impact of these headaches on brain structure and function. Mental health issues often observed in individuals with severe headaches, such as sadness and anxiety, are also associated with the condition of the hippocampus. Brain scans have revealed that individuals experiencing severe headaches and sadness tend to have more hippocampal shrinkage than those who only experience headaches, indicating a possible relationship between feelings of sadness and the condition of the hippocampus and its impact on thinking ability. Furthermore, changes in the hippocampus of individuals with severe and frequent headaches can also affect the perception and management of pain. Researchers have noted that the hippocampus can influence the body’s response to pain, and any changes to its structure might affect an individual’s pain perception and lead to long-term pain in those with severe headaches. Understanding these connections can help in developing specific treatments aimed at reducing the impact of severe headaches on brain health and the overall quality of life. Hippocampal atrophy is present in both patients with chronic migraine with and without aura. Chronic migraine, which is defined as 15 or more headache days per month along with new-onset drug misuse, is more severe than episodic migraine and can lead to brain shrinkage. However, controlled studies have shown that medications for migraine do not affect brain atrophy. A higher prevalence of migraine is linked to lower educational attainment, which is associated with more significant brain atrophy. Furthermore, hippocampal metabolic dysfunction in chronic migraine has been documented, and societal-level changes in the chronic migraine population are related to brain development. A problem in the medial temporal lobe can make it difficult to learn new things and impede neocortical synthesis of theta, which is essential for long-term potentiation-inducing stimulation. Further research is required to understand the accelerated aging associated with chronic migraine and enhance management strategies. Chronic migraine affects intellectual abilities and emotions and has a greater burden than episodic migraine and traumatic brain injury. Notably, accelerated brain aging was observed in chronic migraine, and the increased number of years of brain aging is comparable to the burden of mild traumatic brain injury. Greater hippocampal and temporal lobe atrophy in chronic migraine corresponds to a greater burden of cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease dementia. Even after accounting for white matter hyperintensities, brain age in chronic migraine remains elevated due to the contribution of white matter hyperintensities in underestimating chronological age. This implies that white matter hyperintensity has the effect of downgrading chronological age in brain age estimation, thereby making the true impact of brain aging in these individuals unknown.

| Category | Observations in Chronic Migraine | Implications for Brain Aging | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging | Decreased volume of the hippocampus. Elevated levels of white matter hyperintensities (WMHs). Thinning of the cortex in the frontal and temporal lobes. | These changes are indicators of rapid brain aging and initial neurodegenerative processes. | (87-91) |

| Cognitive Function | The dysfunction observed in episodic and declarative memory among chronic migraine patients significantly impacts their overall cognitive abilities. Additionally, impaired executive functioning and reduced processing speed. | This suggests active involvement of the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex in these cognitive processes. | (92-94) |

| Emotional and Psychiatric Aspects | Increased rates of depression and anxiety. Heightened sensitivity to stress and challenges in emotional regulation. | Disruption of the hippocampal stress response can accelerate emotional aging. | (95-97) |

| Brain Age Gap (BAG) | Increased rates of depression and anxiety. Heightened sensitivity to stress and challenges in emotional regulation. | Disruption of the hippocampal stress response can accelerate emotional aging. | (66, 98-100) |

| Discomfort and Long-term Persistence | Regular nociceptive input and central sensitization. Altered sensory processing pathways. | Continuous activation may lead to neuroinflammation and stress within the hippocampus. | (101-103) |

6. Implications and Future Directions

Recent research has revealed a link between chronic migraines and accelerated brain aging. A study utilizing MRI-based machine learning models found that individuals suffering from chronic migraine exhibited an increased brain age gap (BAG), indicating accelerated brain aging. This BAG correlates with self-reported cognitive decline and performance on cognitive tests. However, these findings must be approached with caution as they originate from a single-center study with a relatively small sample size, highlighting the need for further validation and careful interpretation of the results. Further analysis showed that patients with chronic migraine experienced significant reduction in gray matter volume. This reduction was especially noticeable in the brain regions associated with pain processing and crucial cognitive functions, such as the anterior cingulate cortex, insula, and hippocampus. Notably, changes in hippocampal volume have been linked to the frequency of headaches, suggesting a potential biomarker for predicting migraine prognosis and offering hope for future diagnostic tools. There is a clear need for further investigation that focuses on longitudinal studies. They should utilize neuroimaging methods to investigate the intricacies of aging in the brains of people with chronic migraines and analyze any possible targeted treatment to impede any worsening symptoms and/or slow down the deterioration of the mind. This strategy has the potential to open up the possibilities of better managing and preventing migraines and avoiding long-term deterioration of the neurological condition.

| Recognized Deficiency | Justification | Suggested Research/Initiative |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient longitudinal imaging data | Cross-sectional studies are limited in determining causality or the progression of phenomena. | Conduct prospective cohort studies involving multiple MRI scans and cognitive evaluations. |

| Lack of emphasis on hippocampal atrophy in migraine research | Most studies focus on global brain aging or white matter hyperintensities, neglecting hippocampal atrophy. | Utilize high-resolution structural MRI to assess hippocampal subfields in individuals with chronic migraine. |

| Unverified application of the Brain Age Gap (BAG) as a clinical indicator | While BAG shows potential, it has not yet achieved standardization or widespread validation. | Evaluate the BAG concerning ongoing cognitive decline and the effectiveness of treatments. |

| Ambiguity surrounding the effects of migraine treatments on brain structure | The impact of prophylactic treatments on slowing brain atrophy remains uncertain. | Investigate brain structure changes before and after therapies (e.g., CGRP inhibitors). |

| Insufficient studies on migraine-related brain aging in younger populations | Need to explore how early life exposures affect long-term brain health. | Analyze hippocampal and cognitive changes in younger population. |

7. Conclusion

Chronic migraines linked to a decline in brain health, particularly involving shrinkage of the hippocampus, which is crucial for memory. Advanced neuroimaging has revealed structural changes similar to early neurodegeneration in patients with chronic migraine. Machine learning analyses indicate that they have a Brain Age Gap of over four years older than their actual age, highlighting the difference between predicted brain age and chronological age. MRI studies consistently show reduced hippocampal volume, correlating migraine with cognitive decline. This cognitive deterioration is compounded by emotional challenges; even during headache-free periods, individuals may struggle with episodic memory and executive function. Anxiety and depression often accompany chronic pain, which complicates the patient experience. The factors driving accelerated brain aging in chronic migraineurs include continuous pain signaling and neurogenic inflammation. Additionally, comorbidities, such as obesity and hypertension, can trigger systemic inflammation, further exacerbating brain aging. Future studies ought to build on monitoring of the Brain Age Gap volume loss as a meaningful biomarker of cognitive deterioration in migraine with long-term aims of assessing ways of reducing or inhibiting them. The new method of focusing on the hippocampal atrophy and the fact of such an approach has been biblical is a good base to base further and higher-evidence research. This study forms a basis of specific testable hypothesis of longitudinal studies on bigger scale i.e., monitoring of hippocampal loss in volume as biomarker thus making the study one of the significant contributions to the long-term scientific direction in the field.

Conflict of Interest Statement:

The authors had identified no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement:

None.

Acknowledgements:

The authors had no acknowledgement.

References:

- Bamalan BA, Khojah AB, Alkhateeb LM, Gasm IS, Alahmari AA, Alafari SA, et al. Prevalence of migraine among the general population, and its effect on the quality of life in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Medical Journal. 2021;42(10):1103.

- Ashina M, Terwindt GM, Al-Karagholi MA-M, De Boer I, Lee MJ, Hay DL, et al. Migraine: disease characterisation, biomarkers, and precision medicine. The Lancet. 2021;397(10283):1496-504.

- Mungoven TJ, Henderson LA, Meylakh N. Chronic migraine pathophysiology and treatment: a review of current perspectives. Frontiers in Pain Research. 2021;2:705276.

- Gupta J, Gaurkar SS. Migraine: An underestimated neurological condition affecting billions. Cureus. 2022;14(8).

- Fila M, Pawlowska E, Szczepanska J, Blasiak J. Different aspects of aging in migraine. Aging and Disease. 2023;14(6):2028.

- Gribbin CL, Dani KA, Tyagi A. Chronic migraine: An update on diagnosis and management. Neurology India. 2021;69(Suppl 1):S67-S75.

- Amiri P, Kazeminasab S, Nejadghaderi SA, Mohammadinasab R, Pourfathi H, Araj-Khodaei M, et al. Migraine: a review on its history, global epidemiology, risk factors, and comorbidities. Frontiers in neurology. 2022;12:800605.

- Bakar NA. Multifaceted Insights Into Cluster Headache: Functional Neuroimaging, Saccadometry and Quality of Life: Guy’s, King’s and St. Thomas’s School of Dentistry; 2014.

- Sungura R, Onyambu C, Mpolya E, Sauli E, Vianney J-M. The extended scope of neuroimaging and prospects in brain atrophy mitigation: a systematic review. Interdisciplinary Neurosurgery. 2021;23:100875.

- Humphreys K, Shover CL, Andrews CM, Bohnert AS, Brandeau ML, Caulkins JP, et al. Responding to the opioid crisis in North America and beyond: recommendations of the Stanford Lancet Commission. The Lancet. 2022;399(10324):555-604.

- Liang L, Zhao L, Wei Y, Mai W, Duan G, Su J, et al. Structural and functional hippocampal changes in subjective cognitive decline from the community. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2020;12:64.

- Young PN, Estarellas M, Coomans E, Srikrishna M, Beaumont H, Maass A, et al. Imaging biomarkers in neurodegeneration: current and future practices. Alzheimer’s research & therapy. 2020;12:1-17.

- Lee H-J, Yu H, Gil Myeong S, Park K, Kim D-K. Mid-and late-life migraine is Associated with an increased risk of all-cause dementia and Nationwide Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2021;11(10):990.

- Begasse de Dhaem O, Robbins MS. Cognitive impairment in primary and secondary headache disorders. Current Pain and Headache Reports. 2022;26(5):391-404.

- Zhao L, Tang Y, Tu Y, Cao J. Genetic evidence for the causal relationships between migraine, dementia, and longitudinal brain atrophy. The Journal of Headache and Pain. 2024;25(1):1-10.

- Pereira JB, Janelidze S, Stomrud E, Palmqvist S, Van Westen D, Dage JL, et al. Plasma markers predict changes in amyloid, tau, atrophy and cognition in non-demented subjects. Brain. 2021;144(9):2826-36.

- Salmanzadeh H, Ahmadi-Soleimani SM, Pachenari N, Azadi M, Halliwell RF, Rubino T, et al. Adolescent drug exposure: A review of evidence for the development of persistent changes in brain function. Brain research bulletin. 2020;156:105-17.

- Azam S, Haque ME, Balakrishnan R, Kim I-S, Choi D-K. The ageing brain: molecular and cellular basis of neurodegeneration. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology. 2021;9:683459.

- Houben S, Homa M, Yilmaz Z, Leroy K, Brion J-P, Ando K. Tau pathology and adult hippocampal neurogenesis: What tau mouse models tell us? Frontiers in neurology. 2021;12:610330.

- Innes KE, Sambamoorthi U. The potential contribution of chronic pain and common chronic pain conditions to subsequent cognitive decline, new onset cognitive impairment, and incident dementia: A systematic review and conceptual model for future research. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2020;78(3):1177-95.

- Armstrong NM, An Y, Shin JJ, Williams OA, Doshi J, Erus G, et al. Associations between cognitive and brain volume changes in cognitively normal older adults. Neuroimage. 2020;223:117289.

- Kolbeinsson A, Filippi S, Panagakis Y, Matthews PM, Elliott P, Dehghan A, et al. Accelerated MRI-predicted brain ageing and its associations with cardiometabolic and brain disorders. Scientific Reports. 2020;10(1):19940.

- MacDonald ME, Pike GB. MRI of healthy brain aging: A review. NMR in Biomedicine. 2021;34(9):e4564.

- Statsenko Y, Habuza T, Smetanina D, Simiyu GL, Uzianbaeva L, Neidl-Van Gorkom K, et al. Brain morphometry and cognitive performance in normal brain aging: age-and sex-related structural and functional changes. Frontiers in aging neuroscience. 2022;13:713680.

- Radhakrishnan H, Stark SM, Stark CE. Microstructural alterations in hippocampal subfields mediate age-related memory decline in humans. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2020;12:94.

- Maity MK, Naagar M. A Review on Headache: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Classifications, Diagnosis, Clinical Management and Treatment Modalities. International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR). 2022;11(7):506-15.

- Silvia M, Smith AM. Development and feasibility of the headache-related light and sound sensitivity inventories in youth. Children. 2021;8(10):861.

- Zhang P. Which headache disorders can be diagnosed concurrently? An analysis of ICHD3 criteria using prime encoding system. Frontiers in Neurology. 2023;14:1221209.

- Diener H-C, Tassorelli C, Dodick DW, Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Ashina M, et al. Guidelines of the International Headache Society for controlled trials of preventive treatment of migraine attacks in episodic migraine in adults. Cephalalgia. 2020;40(10):1026-44.

- Özge A. Global burden of headache disorders in children and adolescents. Current pain and headache reports. 2016;20:1-9.

- Guastafierro E, Toppo C, et al. Global burden of headache disorders in children and adolescents 2007 2017. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2021;18(1):250.

- Pozo-Rosich P, Coppola G, Pascual J, Schwedt TJ. How does the brain change in chronic migraine? Developing disease biomarkers. Cephalalgia. 2021;41(5):613-30.

- Wilcox SL, Nelson S, Ludwick A, Youssef AM, Lebel A, Beccera L, et al. Hippocampal volume changes across developmental periods in female migraineurs. Neurobiology of Pain. 2023;14:100137.

- Danieli K, Guyon A, Bethus I. Episodic Memory formation: A review of complex Hippocampus input pathways. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2023;126:110757.

- Homayouni R, Canada KL, Saifullah S, Foster DJ, Thill C, Raz N, et al. Age‐related differences in hippocampal subfield volumes across the human lifespan: A meta‐analysis. Hippocampus. 2023;33(12):1292-315.

- Palomero-Gallagher N, Kedo O, Mohlberg H, Zilles K, Amunts K. Multimodal mapping and analysis of the cyto-and receptor architecture of the human hippocampus. Brain Structure and Function. 2020;225:881-907.

- Zhou Y, Wang G, Liang X, Xu Z. Hindbrain Networks: Exploring the Hidden Anxiety Circuits in Rodents. Behavioural Brain Research. 2024:115281.

- Naguib LE, Abdel Azim GS, Abdellatif MA. A volumetric magnetic resonance imaging study in migraine. The Egyptian Journal of Neurology, Psychiatry and Neurosurgery. 2021;57(1):116.

- Bouzigues A, Godefroy V, Le Du V, Russell L, Houot M, Le Ber I, et al. Disruption of macroscale functional network organisation in patients with frontotemporal dementia. Molecular Psychiatry. 2024:1-12.

- Baumann O, Mattingley JB. Extrahippocampal contributions to spatial navigation in humans: A review of the neuroimaging evidence. Hippocampus. 2021;31(7):640-57.

- Blinkouskaya Y, Weickenmeier J. Brain shape changes associated with cerebral atrophy in Mechanical Engineering. 2021;7:705653.

- Elliott ML, Belsky DW, Knodt AR, Ireland D, Melzer TR, Poulton R, et al. Brain-age in midlife is associated with accelerated biological aging and cognitive decline in a longitudinal birth cohort. Molecular psychiatry. 2021;26(8):3829-38.

- Operto FF, Pastorino GM, Viggiano A, Dell’Isola GB, Dini G, Verrotti A, et al. Epilepsy and cognitive impairment in childhood and adolescence: a mini-review. Current Neuropharmacology. 2023;21(8):1646-65.

- Yulug B, Ayyildiz B, Sayman D, Cankaya S, Duran U, Ucak AD, et al. Altered Hippocampal Connectivity is Associated With Cognitive Impairment in Migraine Patients. 2024.

- Choudhary AK. Migraine and cognitive impairment: the interconnected processes. Brain-Apparatus Communication: A Journal of Bacomics. 2024;3(1):2439437.

- Puledda F, Viganò A, Sebastianelli G, Parisi V, Hsiao F-J, Wang S-J, et al. Electrophysiological findings in migraine may reflect abnormal synaptic plasticity mechanisms: a narrative review. Cephalalgia. 2023;43(8):03331024231195780.

- Argyriou AA, Dermitzakis EV, Xiromerisiou G, Rikos D, Rallis D, Soldatos P, et al. Menopause and its impact on the effectiveness of fremanezumab for migraine prophylaxis: post-hoc analysis of a prospective, real-world Greek registry. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 2024;24(11):1119-26.

- Hohls JK, König H-H, Quirke E, Hajek A. Anxiety, depression and quality of life a systematic review of evidence from longitudinal observational studies. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2021;18(22):12022.

- Moisset X, Giraud P, Dallel R. Migraine in multiple sclerosis and other chronic inflammatory diseases. Revue Neurologique. 2021;177(7):816-20.

- Teleanu DM, Niculescu A-G, Lungu II, Radu CI, Vladâcenco O, Roza E, et al. An overview of oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and neurodegenerative diseases. International journal of molecular sciences. 2022;23(11):5938.

- Vergne-Salle P, Bertin P. Chronic pain and neuroinflammation. Joint Bone Spine. 2021;88(6):105222.

- Amidfar M, Quevedo J, Z. Réus G, Kim Y-K. Grey matter volume abnormalities in the first depressive episode of medication-naïve adult individuals: a systematic review of voxel based morphometric studies. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 2021;25(4):407-20.

- Forkel SJ, Friedrich P, Thiebaut de Schotten M, Howells H. White matter variability, cognition, and disorders: a systematic review. Brain Structure and Function. 2022:1-16.

- Leyane TS, Jere SW, Houreld NN. Oxidative stress in ageing and chronic degenerative pathologies: molecular mechanisms involved in counteracting oxidative stress and chronic inflammation. International journal of molecular sciences. 2022;23(13):7273.

- Ma X, Gao H, Wu Y, Zhu X, Wu S, Lin L. Investigating Modifiable Factors Associated with Cognitive Decline: Insights from the UK Biobank. Biomedicines. 2025;13(3):549.

- Aybakan MN, Gürsoy G, Pazarci N. Changes in the hippocampal volume in chronic migraine, episodic migraine, and medication overuse headache patients. Clinical Neuroscience/Ideggyógyászati Szemle. 2023;76.

- Dubois J, Alison M, Counsell SJ, Hertz‐Pannier L, Hüppi PS, Benders MJ. MRI of the neonatal brain: a review of methodological challenges and neuroscientific advances. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2021;53(5):1318-43.

- Han J, Wu X, Wu H, Wang D, She X, Xie M, et al. Eye-opening alters the interaction between the salience network and the default-mode network. Neuroscience Bulletin. 2020;36:1547-51.

- Lenart-Bugla M, Szcześniak D, Bugla B, Kowalski K, Niwa S, Rymaszewska J, et al. The association between allostatic load and brain: A systematic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2022;145:105917.

- Lin Y-K, Tsai C-L, Lin G-Y, Chou C-H, Yang F-C. Pathophysiology of chronic migraine: insights from recent neuroimaging research. Current Pain and Headache Reports. 2022;26(11):843-54.

- Mokhber N, Shariatzadeh A, Avan A, Saber H, Babaei GS, Chaimowitz G, et al. Cerebral blood flow changes during aging process and in cognitive disorders: A review. The neuroradiology journal. 2021;34(4):300-7.

- Peres MFP, Sacco S, Pozo-Rosich P, Tassorelli C, Ahmed F, Burstein R, et al. Migraine is the most disabling neurological disease among children and adolescents, and second after stroke among adults: A call to action. Cephalalgia. 2024;44(8):03331024241267309.

- Dobrynina LA, Suslina AD, Gubanova MV, Belopasova AV, Sergeeva AN, Evers S, et al. White matter hyperintensity in different migraine subtypes. Scientific Reports. 2021;11(1):10881.

- Eikermann-Haerter K, Huang SY. White matter lesions in migraine. The American journal of pathology. 2021;191(11):1955-62.

- Paolucci M, Altamura C, Vernieri F. The role of endothelial dysfunction in the pathophysiology and cerebrovascular effects of migraine: a narrative review. Journal of clinical neurology (Seoul, Korea). 2021;17(2):164.

- Navarro-González R, García-Azorín D, Guerrero-Peral ÁL, Planchuelo-Gómez Á, Aja-Fernández S, de Luis-García R. Increased MRI-based Brain Age in chronic migraine patients. The Journal of Headache and Pain. 2023;24(1):133.

- Batty GD, Gale CR, Kivimäki M, Deary IJ, Bell S. Comparison of risk factor associations in UK Biobank against representative, general population based studies with conventional response rates: prospective cohort study and individual participant meta-analysis. bmj. 2020;368.

- Chen X-Y, Chen Z-Y, Dong Z, Liu M-Q, Yu S-Y. Regional volume changes of the brain in migraine chronification. Neural Regeneration Research. 2020;15(9):1701-8.

- Hu X, Zhang L, Liang K, Cao L, Liu J, Li H, et al. Sex-specific alterations of cortical morphometry in treatment-naïve patients with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2022;47(11):2002-9.

- Kim SK, Nikolova S, Schwedt TJ. Structural aberrations of the brain associated with migraine: A narrative review. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 2021;61(8):1159-79.

- Rechberger S, Li Y, Kopetzky SJ, Butz-Ostendorf M, Initiative AsDN. Automated high-definition MRI processing routine robustly detects disease patients. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2022;14:832828.

- Planchuelo-Gómez Á, García-Azorín D, Guerrero ÁL, Rodríguez M, Aja-Fernández S, de Luis-García R. Gray matter structural alterations in chronic and episodic migraine: a morphometric magnetic resonance imaging study. Pain Medicine. 2020;21(11):2997-3011.

- Şener DK, Zarifoğ Türkeş N. Comparison of patients with chronic and episodic migraine with healthy individuals by brain volume and cognitive functions. The European Research Journal. 2024:1-15.

- Michels L, Koirala N, Groppa S, Luechinger R, Gantenbein AR, Sandor PS, et al. Structural brain network characteristics in patients with episodic and chronic migraine. The journal of headache and pain. 2021;22:1-13.

- Oschmann M, Gawryluk JR, Initiative AsDN. A longitudinal study of changes in resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging functional connectivity networks during healthy aging. Brain Connectivity. 2020;10(7):377-84.

- de Tommaso M, Vecchio E, Quitadamo SG, Coppola G, Di Renzo A, Parisi V, et al. Pain-related brain connectivity changes in migraine: a narrative review and proof of concept about possible novel treatments interference. Brain sciences. 2021;11(2):234.

- Egglefield DA. Late-Life Depression: The Interplay Between Cerebrovascular Risk, Cortical and Subcortical Atrophy, and Treatment Response: City University of New York; 2024.

- Gerstein MT, Wirth R, Uzumcu AA, Houts CR, McGinley JS, Buse DC, et al. Patient‐reported experiences with migraine‐related cognitive symptoms: Results of the MiCOAS qualitative study. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 2023;63(3):441-54.

- Jafari Z, Kolb BE, Mohajerani MH. Age‐related hearing loss and cognitive decline: MRI and cellular evidence. Annals of the new York Academy of Sciences. 2021;1500(1):17-33.

- Kumar R, Asif S, Bali A, Dang AK, Gonzalez DA. The development and impact of anxiety with migraines: a narrative review. Cureus. 2022;14(6).

- Filippi M, Messina R. The chronic migraine brain: what have we learned from neuroimaging? Frontiers in neurology. 2020;10:1356.

- Martins IP, Maruta C, Alves PN, Loureiro C, Morgado J, Tavares J, et al. Cognitive aging in migraine sufferers is associated with more subjective complaints but similar age-related decline: a 5-year longitudinal study. The Journal of Headache and Pain. 2020;21:1-12.

- Sieberg CB, Lebel A, Silliman E, Holmes S, Borsook D, Elman I. Left to themselves: Time to target chronic pain in childhood rare diseases. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2021;126:276-88.

- Dringenberg HC. The history of long‐term potentiation as a memory mechanism: Controversies, confirmation, and some lessons to remember. Hippocampus. 2020;30(9):987-1012.

- Ishii R, Schwedt TJ, Trivedi M, Dumkrieger G, Cortez MM, Brennan K, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury affects the features of migraine. The Journal of Headache and Pain. 2021;22:1-15.

- Richey LN, Rao V, Roy D, Narapareddy BR, Wigh S, Bechtold KT, et al. Age differences in outcome after mild traumatic brain injury: results from the HeadSMART study. International review of psychiatry. 2020;32(1):22-30.

- Bonanno L, Lo Buono V, De Salvo S, Ruvolo C, Torre V, Bramanti P, et al. Brain morphologic abnormalities in migraine patients: an observational study. The Journal of Headache and Pain. 2020;21:1-6.

- Chong CD, Dumkrieger GM, Schwedt TJ. Structural co‐variance patterns in migraine: a cross‐sectional study exploring the role of the hippocampus. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 2017;57(10):1522-31.

- Liu H-Y, Chou K-H, Lee P-L, Fuh J-L, Niddam DM, Lai K-L, et al. Hippocampus and amygdala volume in relation to migraine frequency and prognosis. Cephalalgia. 2017;37(14):1329-36.

- Maleki N, Becerra L, Brawn J, McEwen B, Burstein R, Borsook D. Common hippocampal structural and functional changes in migraine. Brain Structure and Function. 2013;218:903-12.

- Messina R, Rocca MA, Colombo B, Pagani E, Falini A, Goadsby PJ, et al. Gray matter volume modifications in migraine: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Neurology. 2018;91(3):e280-e92.

- Fernandes C, Dapkute A, Watson E, Kazaishvili I, Chądzyński P, Varanda S, et al. Migraine and cognitive dysfunction: a narrative review. The Journal of Headache and Pain. 2024;25(1):221.

- Kaur J, Bingel U, Kincses B, Forkmann K, Schmidt K. The effects of experimental pain on episodic memory and its top-down modulation: a preregistered pooled analysis. Pain Reports. 2024;9(5):e1178.

- Friedman NP, Robbins TW. The role of prefrontal cortex in cognitive control and executive function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2022;47(1):72-89.

- čičová E, St-Pierre M-K, McKee C, Tremblay M-È. Psychological stress as a risk factor for accelerated cellular aging and cognitive decline: the involvement of microglia-neuron crosstalk. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience. 2021;14:749737.

- Ferguson LA, Leal SL. Interactions of emotion and memory in the aging brain: Neural and psychological correlates. Current Behavioral Neuroscience Reports. 2022;9(1):47-57.

- Ghasemi M, Navidhamidi M, Rezaei F, Azizikia A, Mehranfard N. Anxiety and hippocampal neuronal activity: Relationship and potential mechanisms. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2022;22(3):431-49.

- Acarsoy C, Ikram MK, Ikram MA, Vernooij MW, Bos D. Migraine and brain structure in the elderly: The Rotterdam Study. Cephalalgia. 2024;44(9):03331024241266951.

- Tsai C-L, Chou K-H, Lee P-L, Liang C-S, Kuo C-Y, Lin G-Y, et al. Shared alterations in hippocampal structural covariance in subjective cognitive decline and migraine. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2023;15:1191991.

- Wang L, Dai C, Gao M, Geng Z, Hu P, Wu X, et al. Patients with episodic migraine without aura have an increased rate of delayed discounting. Brain and Behavior. 2024;14(1):e3367.

- Hassamal S. Chronic stress, neuroinflammation, and depression: an overview of pathophysiological mechanisms and emerging anti-inflammatories. Frontiers in psychiatry. 2023;14:1130989.

- Ji R-R, Nackley A, Huh Y, Terrando N, Maixner W. Neuroinflammation and central sensitization in chronic and widespread pain. Anesthesiology. 2018;129(2):343.

- Xiong H-Y, Hendrix J, Schabrun S, Wyns A, Campenhout JV, Nijs J, et al. The role of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor in chronic pain: links to central sensitization and neuroinflammation. Biomolecules. 2024;14(1):71.