Digital Strategies in Rural Healthcare Delivery Models

Hub and Spoke 2.0: A Narrative Review of Digital Strategies in Rural Healthcare Delivery Models

Katelin Morrissette1, MD; Matthew Siket, MD2, MHCI

- Katelin Morrissette, MD Assistant Professor of Medicine and Emergency Medicine, University of Vermont, Larner College of Medicine, University of Vermont Health Network

- Matthew Siket, MD, MHCI Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine and Neurological Sciences, University of Vermont, Larner College of Medicine, University of Vermont Health Network

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 June 2025

CITATION: Morrissette, K., and Siket, M., 2025. Hub and Spoke 2.0: A Narrative Review of Digital Strategies in Rural Healthcare Delivery Models. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(6). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i6.6656

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i6.6656

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

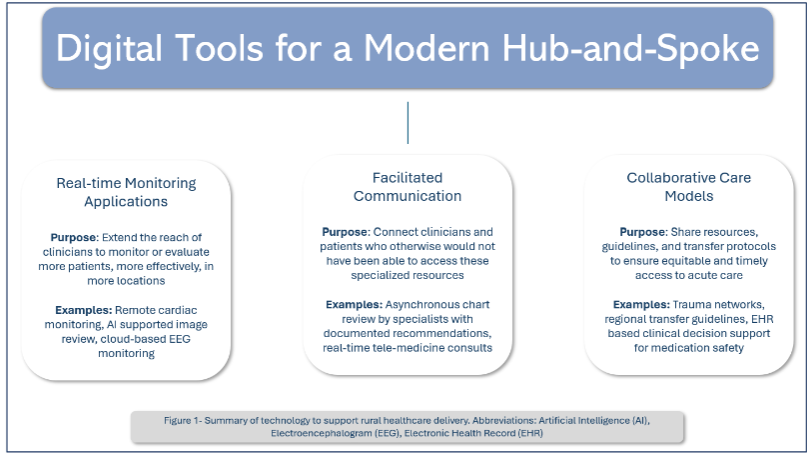

Traditional hub-and-spoke rural healthcare delivery models face persistent challenges in providing timely and equitable access to specialty services. Digital technologies serve an increasingly critical role in mitigating access and capacity constraints by extending the virtual reach of tertiary care centers. A modernized hub-and-spoke design utilizes many forms of digital tools with a diverse range of technological interventions. The goal of this narrative review is to provide a framework for understanding the role and supporting evidence of digital technologies in specialized care in rural regions. We break these digital support tools into three functional groups: 1) real-time monitoring applications including artificial intelligence-based analytics and population-level tools, 2) connected solutions including telemedicine and cloud-connected medical devices, and 3) supportive technologies such as augmented image interpretation, decision support and documentation. These technologies collectively expand the capabilities of healthcare providers to treat acutely ill patients outside of tertiary care centers, enable access to services otherwise unavailable in resource-limited settings, and reduce barriers to maximizing the impact of care capabilities in rural communities. By leveraging a spectrum of digital tools that streamline communication and knowledge sharing, healthcare systems can potentially achieve the quadruple aims of improving patient care, value and sustainability, while supporting equitable access and the well-being of the healthcare workforce.

Keywords

rural healthcare, digital strategies, telemedicine, hub-and-spoke model, healthcare delivery

Introduction

In 1972 Avedis Donabedian wrote, “The proof of access is use of service, not simply the presence of a facility…” He was referencing the complex overlap of the infrastructure and resources necessary to offer a medical service and the overlay of a patient’s relationship with the healthcare services with their ability to engage with the services offered. For example, if a patient presents to a rural hospital, and the emergency department attempts to transfer them for specialty care but an ambulance is unavailable, or the patient is too unstable to transfer, then it is hard to say that patient truly has access to the services in the tertiary care hospital. Disparities in access to healthcare are widening as resources such as broadband internet add layers to the types of access available to some people and not others. This review focuses on models and policies in the United States, however the same access limitations exist worldwide and often share many similar features. For purposes of maintaining a focused scope, this review will be limited to the acute care setting. There is significant overlap in this work related to preventative care, chronic disease management, primary care, and outpatient specialty service access.

Measuring this complex concept of access has been studied for years including process indicators such as the volume of visits or procedures, and outcome measures including cost, mortality, and equity in access to care across patient populations. Patients living in rural regions are more likely to be able to access a primary care provider than a specialist. Yet, limited access to specialists has been linked to preventable hospitalizations and mortality. In the United States, the limited access to specialty care and gaps in technology are among the reasons that rural-urban disparities are a priority for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). There have been several published reports in the last decade focusing on measuring and improving these inequities. Critical Access Hospital (CAH) is a special designation within the United States to reduce the financial vulnerability of small rural hospitals. There is evidence that at CAHs there are both fewer resources and worse measures of quality than at tertiary care centers, highlighting the need to find ways to augment the CAH and rural hospital ability to effectively serve the rural patient population.

There are trends across the United States and elsewhere for healthcare services to consolidate into urban centers, leaving many rural regions without specialist services. This evidence shows benefit from concentrating specialization for many clinical services in regional hospitals, but this requires that rural patients be transferred great distances to receive specialist care. The improved outcomes at centralized, or regional, specialty centers is referred to as the “volume-quality” or “volume-outcome” relationship and can suggest that concentrating specialization in high volume centers improves patient outcomes. This has been demonstrated repeatedly across conditions such as stroke, trauma, respiratory failure, and other. However, one drawback of evaluating outcomes based on hospital level data is that this can fail to account for the scenario in which a patient, at a rural hospital, is either too unstable for a transfer, or is unable to access the tertiary site due to environmental constraints such as weather, hospital capacity, or EMS availability, contribute to worse outcomes. In these instances the better option for that individual patient may well have been a more distributed service network, even though outcomes appear better at large volume centers. Further, consolidation of healthcare systems may be motivated by integration of service to improve outcomes, but may also occur when there are financial pressures. There is a difference between reducing coverage of specialists in rural regions, and development of integrated care networks where specialists assume a duty to the rural communities in their region. Consolidation without service integration is less likely to benefit patients than intentional service line optimization. It is imperative to balance the benefits a patient may receive from treatment at high volume centers, by experienced specialists, with the cost and practicality constraints of distributing all specialties into rural areas. The following outline is meant to characterize just some of the available evidence for how specialized skills can be brought to rural patients in their community hospitals.

Methods:

A structured literature search was performed on PubMed utilizing the following search terms: “digital health”, “telemedicine”, “telehealth”, “remote monitoring”, “rural health”, and “specialty care.” Studies were appraised based on relevance, methodological rigor and contribution to the understanding of how digital technologies influence rural healthcare delivery models.

1. REALTIME MONITORING APPLICATIONS

Realtime technologies provide in-the-moment patient data to a clinician who is not necessarily present at the bedside. In particular, when patient monitoring is augmented by artificial intelligence (AI) a clinician can be prompted to respond to data that otherwise may not have been continuously monitored, or can serve a much larger patient volume than had they been required to monitor continuous data for each individual patient. Here we present several examples of a growing body of monitoring technologies to extend the reach of specialists into rural communities and hospitals.

Radiologists were some of the earliest investigators of potential applications of artificial intelligence to optimize ordering practices, triage screening exam review, reduce the image acquisition time. Using AI tools has been shown to improve accuracy in chest radiograph interpretation up to 10% and has reduced the workload of mammography screening by more than 33%. As AI tools have improved the evidence is growing for standardized and evidence based applications of these tools. The nature of radiology is such that there is a rich source of digital data including oncologic, infectious, and procedural guidance feature. The practice of remote image review pre-dated the AI augmented image review and likely served to support an adoption of technology that enhances the remote patient care efficiency, as opposed to use in specialties which have traditionally been practiced at the bedside.

Remote cardiac monitoring with implantable cardiac devices such as permanent pacemakers (PPMs) and automatic implanted defibrillators (AIDs) have existed for decades and are now available with wireless cloud-based connections. When automated daily event monitoring was paired with standard care the remote monitoring outperformed standard care alone with a 30% reduction in a combined endpoint of hospitalization, all cause mortality, or clinical decline. In particular this serves rural communities when the patient is prompted to connect with their physician early. Barriers such as long commute times, inclement weather, and transportation costs can reduce likelihood of rural patients seeking early care, and when remote monitoring promotes phone conversations rather than hospitalization patients may be more likely to adjust treatments or avoid complications.

Real-time Patient Monitoring (RPM) in cardiac devices have primarily been evaluated in patients in homes, but technologies also exist which serve to support community hospitals in expanding their capabilities. This can offer much the same benefit in terms of reducing capacity constraints in tertiary centers but has the added benefit of supporting the financial stability of community hospitals, many of which operate just above the threshold of sustainability.

Very similar to the electrical cardiac signals, the electrical signals of brain function can be interpreted by AI tools. The rapid electroencephalography (EEG) AI based “Clarity” algorithm allows for the automated detection and diagnosis of status epilepticus (SE) using a headband which can be placed by a bedside nurse without the need for dedicated EEG technician. This tool was demonstrated to be 100% sensitive and 92% specific in detection of SE. Because of this high level of accuracy it has been used to change management in up to 53% of patients, expedites disposition in 21% of cases, reduce need to transfer a patient to a tertiary care center. Implementation of this bedside testing device has been demonstrated to improve utilization of this testing in community sites, suggesting that rural patients were being under tested compared to their urban counterparts. The same tool was deployed in academic centers resulting in shorter wait from time of ordering to time of monitoring.

The potential value of remote monitoring systems also expands beyond physician roles. For example, pharmacist review of medications during a hospital admission has been shown to reduce the incidence of drug interactions or erroneous prescribing. Levinen et al use AI based decision support to reduce drug related problems from 15.3% in high risk medications and 2.8% in low risk medications. With the advent of natural language processing (NLP) and optical character recognition (OCR) there is an opportunity to expand this service to locations which do not have in-house pharmacists around the clock.

2. FACILITATED COMMUNICATION

Real-time video-based telemedicine skyrocketed during the COVID-19 pandemic and is proving sustainable in rural settings to reduce disparities in access to care. In the emergency setting, telemedicine has demonstrated benefit in both the prehospital and ED epochs of care. Tele-Emergency Medical Services (EMS) provides a means for advanced video-enhanced medical direction to bolster interventions of first responders in the field. Tele-Emergency Medicine (EM) has been used to augment a rural emergency provider workforce to support time-sensitive and complex decision-making such as in stroke, trauma, and critical illness. Tele-guidance applications are available for bedside procedures such as endotracheal intubation and point-of-care ultrasound and are marketed as quality assurance/improvement and precepting tools. These programs have been shown to elevate the standard of care delivered in resource-limited settings while potentially avoiding unnecessary transfers. Moreover, when used in a rural hub and spoke network without EM trained physicians in all rural spoke sites, the use of Tele-EM was associated with a 31% reduction in total annual ED costs.

In rural hospital settings with limited access to tertiary care, Tele-Intensive Care and Tele-Specialty Consultation has provided a virtual means to connect high-level expertise to settings where these services would otherwise be unavailable. Tele-ICU has demonstrated efficacy in bridging care for critically ill patients and obviating the need for transfer altogether in some instances. Tele-intensivists have been shown to improve compliance with standards of care and reduce mortality; their involvement may identify the need for a transfer rather than avoid it. This is evidence that when evaluating the value or impact of a service there must be a more comprehensive evaluation than simply the number of transfers or the revenue from fee-for-service.

For highly specialized fields such as neurology, there remain widespread provider deserts across much of the rural US and globally. However, timely access to neurological expertise has been shown to correlate to improved outcomes for patients with acute ischemic stroke. Tele-stroke services are associated with lower 30-day mortality and improved health outcomes. Neurology is just one of several specialties that are able to directly improve rural care delivery thanks to virtual solutions. As stated previously this depends both on the technological infrastructure, such as broadband internet access, and on the collaboration between the rural and specialty centers. This collaboration may also have impact in instances where technology is less available or necessary.

3. COLLABORATION AND SYSTEM INTEGRATION:

Traditional hub and spoke models include many elements with significant value even with low, or no, need for technology at all. For example, integrated care networks have been utilized in stroke, trauma, and cancer care models. Some of these networks operate in formal referral structures and shared electronic health record (EHR) systems, others form networks strictly by referral practices and form nodes of influence through capacity or treatment capabilities.

In the United States there is a formalized definition of trauma center designations based on the available services, volume of high acuity traumas, and regional leadership. Part of the level 1 trauma designation is an obligation to serve as the regional referral center and to support smaller regional hospitals as the accepting center when a trauma exceeds their management capabilities. Due to this formalized regional partnership and standardized reporting structures there is a growing body of evidence for the disposition and outcomes for trauma patients transferred into regional referral centers. When a patient is transferred to a regional referral center, and is then identified to have had injuries which may not have required any services that were unavailable at the originating site this is termed “secondary over triage.” Secondary over triage has been identified as a contributing factor in unnecessary resource utilization, unnecessary use of emergency medical services (EMS) transfers, and patient/family dissatisfier when a patient is unnecessarily moved far from their community. To address this there has been work to establish which groups of patients may be low enough risk to remain in community hospitals despite significant traumatic injuries.

The modified Brain Injury Guidelines (mBIG) are a set of radiologic and clinical criteria used to risk stratify patients with traumatic intracranial hemorrhage. In the lowest risk category, mBIG-1, published studies have demonstrated that patients are able to safely remain in their community hospitals without deterioration or need for invasive procedures. This has been successfully implemented in rural and urban hospital partnerships to both reduce unnecessary transfers and to improve consistency in risk stratifying traumatic intracranial bleeding.

Just as there are regional trauma centers one can imagine regional specialty centers for many medical conditions. In such a model, not all patients would necessarily require transfer, however shared guidelines on testing, treatment, and transfer could offer opportunities for standardizing care and improving resource utilization. For example, asthma related rates of emergency department visits, hospitalization, and healthcare costs were significantly reduced in Asheville, North Carolina, USA, after “The Asheville Project” was implemented. This project was focused on coordinating care between academic medical institutions, creating partnerships with community organizations to promote learning opportunities, and recruiting a local workforce to support evidence-based treatment for patients with chronic respiratory disease.

Clinical decision support (CDS) is a broad term which can encompass access to medical guidelines, EHR integrated prompting tools, and advanced AI based proscriptive medical guidance. As AI and EHR capabilities grow there may be more advanced CDS available. The wide range of tools available makes CDS an appealing solution to many clinical challenges. However, success of any CDS system depends on the implementation and culture of adaptation. In one study, Stevensen et al deployed a powerful CDS tool for antimicrobial management in 5 rural hospitals. While the tool overall was impactful data review demonstrated wide variability in impact, which was identified to be primarily driven by the organization and implementation of the tool. Just as in the 1972 quote from Donabedian, the availability of a tool does not mean that there is true access to this value unless users know when and how to use it, and have the right incentives to seek it out.

While the scope of this review is largely limited to acute care settings we would be remiss to neglect noting the impact that preventative care and shared EHR communications can have in ensuring continuity of care, social support services, and symptom management. Further research and documentation of these services would be a valuable addition to the knowledge base in how rural patients can access the same standards of services available in more urban or academic settings. Across the world policy makers are thinking about how to preserve and improve access to healthcare in rural communities. Some of the approaches outlined herein may serve as examples of how collaboration can be sued to connect a small volume of highly trained medical specialists to rural communities using a combination of high and low tech solutions.

Discussion and Conclusions

The advancement of digital technologies offers promising opportunities to address long-standing geographic disparities in healthcare delivery. This narrative review has explored a spectrum of digital strategies within rural healthcare delivery models, which can be conceptualized as a modernized “Hub and Spoke 2.0” framework. The evidence presented suggests that digital integration can democratize specialty care access while preserving the financial viability of rural healthcare institutions.

The tripartite categorization of digital interventions—real-time applications, connected solutions, and supportive technologies—provides a conceptual framework for healthcare systems to strategically deploy resources based on clinical needs, technological capabilities, and regional constraints. Remote patient monitoring, facilitated communication, and system integration each represent distinct but complementary approaches that, when implemented in concert, have demonstrated improvements in clinical outcomes, patient experience, operational efficiency, and equitable access.

Critical to the success of any Hub and Spoke 2.0 model is bidirectional collaboration between tertiary centers and rural facilities. Rather than reinforcing hierarchical relationships, effective implementation requires the recognition that rural institutions possess unique insights into their communities’ needs and constraints. The hub-spoke relationship must evolve from simple referral pathways to collaborative partnerships with shared governance, standardized protocols, and mutual accountability. This collaborative paradigm acknowledges that expertise flows in multiple directions, with rural clinicians often developing innovative approaches to resource-limited care delivery that may benefit the entire system.

Significant challenges persist in implementing these digital strategies. Infrastructure limitations, particularly inconsistent broadband connectivity in rural regions, create new forms of digital disparity that may exacerbate rather than ameliorate access inequities. Financial sustainability remains precarious, as reimbursement models have yet to fully align with digital care delivery modalities. Moreover, workforce development must address the digital literacy needs of both clinicians and patients to ensure technological solutions achieve their intended impact.

The research landscape regarding digital rural healthcare interventions remains heterogeneous and methodologically variable. While promising, many studies lack rigorous control groups, standardized outcome measures, or sufficient statistical power to generate definitive conclusions. Implementation science approaches are needed to evaluate how evidence-based digital interventions can be adapted to diverse rural contexts without compromising fidelity. Future research should employ mixed-method designs that capture both quantitative clinical outcomes and qualitative elements of patient and provider experience.

Perhaps most importantly, the evidence base must expand to assess longitudinal outcomes beyond immediate clinical metrics. The quadruple aim framework—enhancing patient experience, improving population health, reducing costs, and improving the work life of healthcare providers—offers a comprehensive evaluative structure for assessing the true impact of digital rural healthcare interventions. Particular attention should be paid to outcomes related to health equity, as technological solutions may inadvertently widen disparities if not intentionally designed to mitigate existing inequities.

As Donabedian astutely observed fifty years ago, access is ultimately validated by utilization rather than mere availability. The modern Hub and Spoke model must therefore be continuously refined through iterative evaluation and adaptation based on empirical evidence. Healthcare systems, academic institutions, and policymakers must collaborate to generate this evidence through systematic implementation and evaluation of digital healthcare delivery innovations. Only through such evidence-based system design can we ensure that rural patients receive equitable, high-quality specialty care regardless of geographic location, thereby fulfilling healthcare’s fundamental promise of serving all communities with excellence and compassion.

References:

- Donabedian A. Models for Organizing the Delivery of Personal Health Services and Criteria for Evaluating Them. The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. 1972;50(4):103-154.

- Ridge A, Peterson GM, Nash R. Risk Factors Associated with Preventable Hospitalisation among Rural Community-Dwelling Patients: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19(24):16487.

- Levesque JF, Harris MF, Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health. Mar 11 2013;12:18.

- Yamashita T, Kunkel SR. The association between heart disease mortality and geographic access to hospitals: county level comparisons in Ohio, USA. Soc Sci Med. Apr 2010;70(8):1211-1218.

- Lurie N, Dubowitz T. Health Disparities and Access to Health. JAMA. 2007;297(10):1118-1121.

- Barreto T, Jetty A, Eden AR, Petterson S, Bazemore A, Peterson LE. Distribution of Physician Specialties by Rurality. The Journal of Rural Health. 2021;37(4):714-722.

- Johnston KJ, Wen H, Joynt Maddox KE. Lack Of Access To Specialists Associated With Mortality And Preventable Hospitalizations Of Rural Medicare Beneficiaries. Health Affairs. 2019;38(12):1993-2002.

- Pichan C, and DeVore AD. Rural and urban hospitals in the United States: does location affect care and outcomes of patients with heart failure? Expert Review of Cardiovascular Therapy. 2024/03/03 2024;22(1-3):1-3.

- Shen YC, Hsia RY. Does decreased access to emergency departments affect patient outcomes? Analysis of acute myocardial infarction population 1996-2005. Health Serv Res. Feb 2012;47(1 Pt 1):188-210.

- Martino S, Elliott, MN, Dembosky, JW, Haas, A, Klein, DJ, Gildner, J, and Haviland, AM. Rural-Urban Disparities in Health Care in Medicare. In: Health COoM, ed. Baltimore, MD; 2023.

- Michelle Mills RW, PA-C National Rural Health Association Policy Brief: Quality improvement in rural health care. In: NRHA, ed; 2023.

- Turrini G BD, Chen L, Conmy AB, Chappel AR, and De Lew N. Access to Affordable Care in Rural America: Current Trends and Key Challenges (ResearchReport No. HP-2021-16). In: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation USDoHaH, ed; 2021.

- Joynt KE, Harris Y, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Quality of Care and Patient Outcomes in Critical Access Rural Hospitals. JAMA. 2011;306(1):45-52.

- Feazel L, Schlichting AB, Bell GR, et al. Achieving regionalization through rural interhospital transfer. Am J Emerg Med. Sep 2015;33(9):1288-1296.

- Nathens AB, Jurkovich GJ, Maier RV, et al. Relationship Between Trauma Center Volume and Outcomes. JAMA. 2001;285(9):1164-1171.

- Sewalt CA, Wiegers EJA, Venema E, et al. The volume-outcome relationship in severely injured patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2018;85(4):810-819.

- Nguyen Y-L, Wallace DJ, Yordanov Y, et al. The Volume-Outcome Relationship in Critical Care. Chest. 2015/07/01/ 2015;148(1):79-92.

- Mesman R, Westert GP, Berden BJMM, Faber MJ. Why do high-volume hospitals achieve better outcomes? A systematic review about intermediate factors in volume–outcome relationships. Health Policy. 2015/08/01/ 2015;119(8):1055-1067.

- Branas CC, MacKenzie EJ, Williams JC, et al. Access to Trauma Centers in the United States. JAMA. 2005;293(21):2626-2633.

- Gaynor M, Town R. The Impact of Hospital Consolidation – Update; 2012.

- Boeken T, Feydy J, Lecler A, et al. Artificial intelligence in diagnostic and interventional radiology: Where are we now? Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging. 2023/01/01/ 2023;104(1):1-5.

- Ahn JS, Ebrahimian S, McDermott S, et al. Association of Artificial Intelligence-Aided Chest Radiograph Interpretation With Reader Performance and Efficiency. JAMA Netw Open. Aug 1 2022;5(8):e2229289.

- Lauritzen AD, Lillholm M, Lynge E, Nielsen M, Karssemeijer N, Vejborg I. Early Indicators of the Impact of Using AI in Mammography Screening for Breast Cancer. Radiology. Jun 2024;311(3):e232479.

- Varma N, Epstein AE, Irimpen A, Schweikert R, Love C. Efficacy and safety of automatic remote monitoring for implantable cardioverter-defibrillator follow-up: the Lumos-T Safely Reduces Routine Office Device Follow-up (TRUST) trial. Circulation. Jul 27 2010;122(4):325-332.

- Parthiban N, Esterman A, Mahajan R, et al. Remote Monitoring of Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. Jun 23 2015;65(24):2591-2600.

- Hindricks G, Taborsky M, Glikson M, et al. Implant-based multiparameter telemonitoring of patients with heart failure (IN-TIME): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. Aug 16 2014;384(9943):583-590.

- Craig W, Ohlmann S. The Benefits of Using Active Remote Patient Management for Enhanced Heart Failure Outcomes in Rural Cardiology Practice: Single-Site Retrospective Cohort Study. J Med Internet Res. 2024/11/26 2024;26:e49710.

- Murphy KM, Hughes LS, Conway P. A Path to Sustain Rural Hospitals. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1193-1194.

- Ward J, Green A, Cole R, et al. Implementation and impact of a point of care electroencephalography platform in a community hospital: a cohort study. Frontiers in Digital Health. 2023-August-07 2023;Volume 5 – 2023.

- Kurup D, Davey Z, Hoang P, et al. Effect of rapid EEG on anti-seizure medication usage. Epileptic Disord. Oct 1 2022;24(5):831-837.

- Wright NMK, Madill ES, Isenberg D, et al. Evaluating the utility of Rapid Response EEG in emergency care. Emerg Med J. Dec 2021;38(12):923-926.

- Eberhard E, Beckerman SR. Rapid-Response Electroencephalography in Seizure Diagnosis and Patient Care: Lessons From a Community Hospital. J Neurosci Nurs. Oct 1 2023;55(5):157-163.

- Graabæk T, Kjeldsen LJ. Medication Reviews by Clinical Pharmacists at Hospitals Lead to Improved Patient Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 2013;112(6):359-373.

- Levivien C, Cavagna P, Grah A, et al. Assessment of a hybrid decision support system using machine learning with artificial intelligence to safely rule out prescriptions from medication review in daily practice. Int J Clin Pharm. Apr 2022;44(2):459-465.

- Edrees H, Song W, Syrowatka A, Simona A, Amato MG, Bates DW. Intelligent Telehealth in Pharmacovigilance: A Future Perspective. Drug Safety. 2022/05/01 2022;45(5):449-458.

- Lee EC, Grigorescu V, Enogieru I, et al. Updated National Survey Trends in Telehealth Utilization and Modality (2021-2022): Issue Brief. Washington (DC); 2023.

- O’Sullivan S, Schneider H. Comparing effects and application of telemedicine for different specialties in emergency medicine using the Emergency Talk Application (U-Sim ETA Trial). Scientific Reports. 2023/08/16 2023;13(1):13332.

- Dean K, Chang C, McKenna E, et al. A retrospective observational study of vCare: a virtual emergency clinical advisory and transfer service in rural and remote Australia. BMC Health Serv Res. Jan 18 2024;24(1):100.

- Choi W, Lim Y, Heo T, et al. Characteristics and Effectiveness of Mobile- and Web-Based Tele-Emergency Consultation System between Rural and Urban Hospitals in South Korea: A National-Wide Observation Study. J Clin Med. Sep 28 2023;12(19).

- Williams D, Jr., Simpson AN, King K, et al. Do Hospitals Providing Telehealth in Emergency Departments Have Lower Emergency Department Costs? Telemed J E Health. Sep 2021;27(9):1011-1020.

- Pannu J, Sanghavi D, Sheley T, et al. Impact of Telemedicine Monitoring of Community ICUs on Interhospital Transfers. Crit Care Med. Aug 2017;45(8):1344-1351.

- Fusaro MV, Becker C, Scurlock C. Evaluating Tele-ICU Implementation Based on Observed and Predicted ICU Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Critical Care Medicine. 2019;47(4).

- McGinley MP, Harvey T, Lopez R, Ontaneda D, Buchalter RB. Geographic Disparities in Access to Neurologists and Multiple Sclerosis Care in the United States. Neurology. Jan 23 2024;102(2):e207916.

- MacKinnon NJ, Emery V, Waller J, et al. Mapping Health Disparities in 11 High-Income Nations. JAMA Netw Open. Jul 3 2023;6(7):e2322310.

- Wilcock AD, Schwamm LH, Zubizarreta JR, et al. Reperfusion Treatment and Stroke Outcomes in Hospitals With Telestroke Capacity. JAMA Neurol. May 1 2021;78(5):527-535.

- Zachrison KS, Dhand A, Schwamm LH, Onnela J-P. A network approach to stroke systems of care. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2019;12(8):e005526.

- Services CfMM. Guidance for Rural Emergency Hospital Provisions, Conversion Process and Conditions of Participation. In: SERVICES DOHH, ed. Baltimore, Maryland Center for Clinical Standards and Quality; 9/6/2024.

- Sorensen MJ, von Recklinghausen FM, Fulton G, Burchard KW. Secondary Overtriage: The Burden of Unnecessary Interfacility Transfers in a Rural Trauma System. JAMA Surgery. 2013;148(8):763-768.

- Nene RV, Corbett B, Lambert G, et al. Identification and management of low-risk isolated traumatic brain injury patients initially treated at a rural level IV trauma center. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2024/04/01/ 2024;78:127-131.

- Krause KL, Brown A, Michael J, et al. Implementation of the Modified Brain Injury Guidelines Might Be Feasible and Cost-Effective Even in a Nontrauma Hospital. World Neurosurgery. 2024/07/01/ 2024;187:e86-e93.

- Fraher EP, Lombardi B, Brandt B, Hawes E. Improving the Health of Rural Communities Through Academic-Community Partnerships and Interprofessional Health Care and Training Models. Acad Med. Sep 1 2022;97(9):1272-1276.

- Stevenson KB, Barbera J, Moore JW, Samore MH, Houck P. Understanding keys to successful implementation of electronic decision support in rural hospitals: analysis of a pilot study for antimicrobial prescribing. Am J Med Qual. Nov-Dec 2005;20(6):313-318.

- Rechel B, Džakula A, Duran A, et al. Hospitals in rural or remote areas: An exploratory review of policies in 8 high-income countries. Health Policy. 2016/07/01/ 2016;120(7):758-769.