Iron Deficiency in Athletes: Insights for Sports Nutrition

Iron deficiency in Athletes – Challenges and Future of Sports Nutrition

Ryunosuke Takahashi1, Katsuhiko Hata2, Koji Okamura3, Takako Fujii2

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 27 Febuary 2025

CITATION: TAKAHASHI, Ryunosuke et al. Iron deficiency in Athletes – Challenges and Future of Sports Nutrition. Medical Research Archives. Available at: <https://esmed.org/MRA/mra/article/view/6354>.

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

ISSN 2375-1924

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i2.6354

ABSTRACT

Iron deficiency is one of the world’s most common nutritional problems: according to the WHO, approximately 30% of the female population aged 15-49 years suffers from iron deficiency anemia. Women are more likely than men to have inadequate dietary iron intake. Women are also more likely to suffer from iron deficiency because iron is also lost through menstrual bleeding. Many athletes, not just women, have also been diagnosed with iron deficiency. Iron plays an important role in oxygen transport and energy metabolism in the body and is therefore very important for athletes with high oxygen requirements, especially endurance athletes. However, despite its importance, many studies, particularly in endurance athletes, have shown a tendency towards low serum ferritin levels. This paper focuses on iron deficiency in athletes and describes the relationship between iron deficiency and exercise. Particular attention will be paid to the effects of different types of exercise on iron nutritional status and the issues that arise.

Keywords: Athlete, Aerobic exercise, Resistance exercise, iron deficiency, Sports nutrition

Introduction

Iron is a micronutrient found in very small amounts in the body, but it plays an important role in processes such as oxygen transport and energy metabolism. Iron is also an essential component of hemoglobin, which is required for oxygen transport in red blood cells. Therefore, iron deficiency in an athlete’s body reduces the oxygen transport capacity of active muscles, leading to a decline in athletic performance. In other words, iron is a very important nutrient for athletes with high oxygen requirements, especially endurance athletes. Despite its importance, many athletes have been diagnosed with iron deficiency. Research has been ongoing for a long time, irrespective of athletes.

There have been many studies of the effects of exercise and diet on iron status, and it is known that exercise itself alters iron status. In particular, many studies of athletes have shown a tendency for serum ferritin levels to be low. Many results support this in endurance athletes. Iron deficiency anemia is the most common nutritional disorder in female athletes, and many of these are thought to be due to dietary iron deficiency. However, people who participate in intense exercise are thought to need more iron than non-athletes due to loss of cellular iron caused by excessive sweating and shedding of epithelial cells from the skin and digestive tract, reduced absorption of iron from the digestive tract, and destruction of blood cells due to the intense physical impact on the legs and other parts of the body during some types of exercise. The incidence of iron deficiency is high not only in athletes but also in people who exercise regularly, and most of these cases involve aerobic exercise, so most research on the effects of exercise and the body’s iron nutritional status has been conducted on aerobic exercise. However, few studies have focused on resistance exercise. In recent years, the effect of resistance exercise in improving iron nutritional status has been suggested. Therefore, we will focus on the different effects of aerobic and resistance exercise on the iron nutritional status of iron-deficient athletes, as well as the issues necessary for the prevention and improvement of iron-deficient athletes, which will be discussed below.

Iron distribution in the body

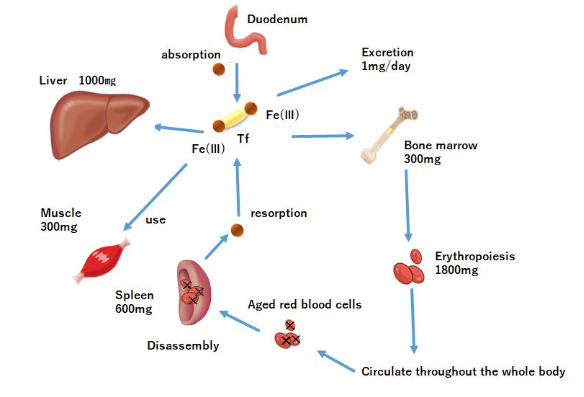

Approximately 60–70% of the iron in the whole body is present as part of the hemo in the hemoglobin.

Hemo iron, other than hemoglobin, accounts for approximately 5% of iron in vivo and acts as an oxygen transporter in tissues. Non-hemo iron enzymes include those involved in oxidation reactions. In mitochondria, these non-hemo iron enzyme groups are more abundant than in cytochromes. Approximately 25% of the body’s iron is stored as ferritin and hemosiderin. When iron loss is less than iron intake, apoferritin synthesis increases with increasing iron intake, and iron adsorption onto ferritin within free polyribosomes proceeds, increasing ferritin stores in the liver. At the same time, hepatic hemosiderin stores are increased, apoferritin synthesis in the reticuloendothelial system and in the endoplasmic reticulum of hepatocytes is enhanced, and serum ferritin is also increased. Conversely, when iron loss is greater than iron uptake, iron is released from ferritin in the liver and serum iron concentration increases. In addition, iron stored in the reticular system and hepatocytes is released into the peripheral blood at a rate of approximately 20–25 mg/day, while serum iron is taken up by erythroblasts (in the bone marrow). Iron incorporated into erythroblasts is used for hemoglobin synthesis, and erythroblasts differentiate into erythrocytes and are released into the peripheral blood. Erythrocytes released into the peripheral blood eventually age and are phagocytosed by reticuloendothelial macrophages. Approximately 85% of the iron in erythrocytes phagocytosed by reticuloendothelial macrophages is released back into the body in the form of transferrin and ferritin, and the remainder is stored in the form of ferritin. Thus, iron uptake into erythroblasts is complemented and maintained by iron supply from macrophages.

The aim of this study was to understand iron metabolism in vivo and to provide a clear assessment of the challenges in sports nutrition.

Regulation of iron in the body

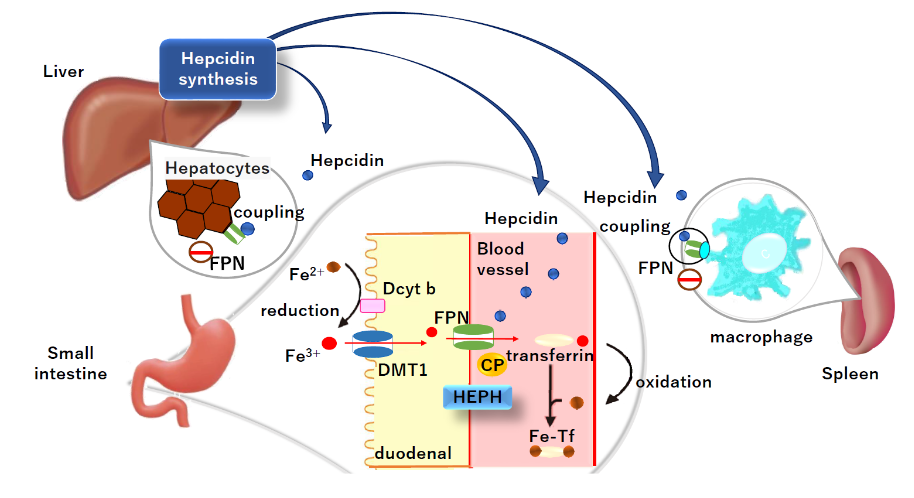

Many studies have been conducted on the effects of training and nutrition (nutrients) on athletes. In particular, hepcidin, an iron-regulating hormone synthesized in the liver, has attracted considerable attention. Hepcidin plays an important role in iron homeostasis. Hepcidin, a peptide hormone, is secreted by hepatocytes. The main iron flux of hepcidin is shown in

Dietary iron is primarily absorbed in the duodenum. Hepcidin also negatively regulates the release of recycled iron from macrophages and stored iron from hepatocytes. Iron and hepcidin regulate each other via endocrine feedback. When iron is high, hepcidin production by hepatocytes increases, limiting iron uptake and the release of stored iron. When iron is deficient, hepcidin production by hepatocytes is reduced and more iron is released into the plasma. Specific forms of iron that increase hepcidin synthesis include diiron plasma transferrin and hepatocyte-stored iron.

In iron deficiency, low hepcidin levels increase ferroportin activity in duodenal epithelial cells and reduce iron stores in intestinal epithelial cells. Iron deficiency in intestinal epithelial cells reduces the activity of oxygen- and iron-dependent prolyl hydroxylases, which target hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) for degradation in the proteasome and stabilization of HIF. HIF2α is an apical iron importer. Normalization of HIF2α regulates dietary iron import into the apex and the activity of hepcidin-regulated ferroportins, and increases intestinal iron absorption in iron-deficient states. Both extracellular iron (in the form of iron transferrin) and intracellular iron regulate hepcidin synthesis. However, the mechanism underlying intracellular iron sensing remains unclear.

Dietary iron contains two main types of iron: heme iron and non-heme iron. However, it is known that the majority of dietary iron intake is non-heme iron. Dcytb at the intestinal epithelial cell membrane reduces non-heme iron to divalent iron, which is then taken up into the cell by DMT1. The heme iron and the iron taken up by the intestinal epithelial cells are transported to the cytoplasm by heme carrier protein 1 (HCP1). It is then degraded by heme oxygenase and released as an iron ion. Iron in the cytoplasm is exported into the circulation by ferroportins located in the basement membrane of the intestinal epithelium. The iron released from ferroportin is oxidized to trivalent iron by membrane-bound hefaestin or soluble ceruloplasmin. It is then bound to transferrin in the blood and transported in a safe form for distribution throughout the body.

Iron deficiency

Iron storage deficiency can occur rapidly or very slowly, depending on the balance between iron intake, storage, and iron requirements. Furthermore, the rate at which true iron deficiency occurs in individual tissues and intracellular organelles depends on the intracellular mechanisms of iron recycling and the metabolic turnover rate of iron-containing proteins. Iron is also responsible for transporting oxygen to the muscles during exercise and plays an important role in energy production during exercise. Therefore, iron deficiency leads to reduced athletic performance in endurance sports. Several physiological mechanisms have been proposed to explain iron depletion, including gastrointestinal hemorrhage, hemolysis due to impact, such as on plantar surfaces, iron deficiency in the daily diet, and loss due to heavy sweating. In addition, iron metabolism disorders, such as iron recycling from the spleen and macrophages, and iron absorption in the duodenum via hepcidin, are associated with iron deficiency. Hepcidin regulates iron homeostasis by binding to ferroportin, the only known intracellular iron exporter, and inhibiting its function through occlusion or degradation. Hepcidin plays an important role in iron metabolism in the body. The basolateral membrane contains an iron transporter called ferroportin, which removes iron from the cells. Hepcidin regulates iron levels by binding to ferroportin. In other words, hepcidin produced in the liver binds to ferroportin, and moves from the cell membrane to inside the cell, where it is degraded in lysosomes. When iron is not needed, hepcidin levels increase, leading to a decrease in ferroportin and suppression of iron transport. Conversely, when iron is needed, hepcidin expression decreases, allowing ferroportin to promote iron transport. Under normal conditions, blood iron levels are regulated. However, when excess iron is administered or during inflammation, hepcidin is overproduced, leading to a state of functional iron deficiency where stored iron cannot be utilized. Measuring blood hepcidin concentration is important for determining whether iron metabolism is normal.

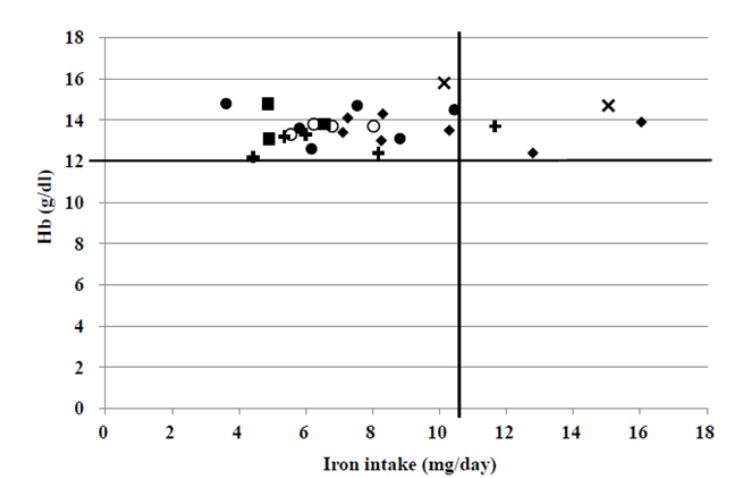

Currently, anemia is mainly measured by hemoglobin concentration, which the WHO defines as less than 13 g/dl in men and 12.0 mg/dl in women. Furthermore, in recent years, blood ferritin levels, which reflect iron stores, have garnered attention for determining iron deficiency. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a serum ferritin concentration of 15 ng/mL as the cutoff value for iron deficiency in healthy individuals (10-59 years). Many studies have used a serum ferritin cutoff of >30 ng/mL, while broader ranges such as 12-40 ng/mL have also been employed in research on iron deficiency and metabolism. However, Galetti et al., in a study investigating the association of serum ferritin, hepcidin, and iron absorption in young women, recommended a ferritin cutoff of 50 ng/mL for the early detection of iron deficiency. Nachtigall et al. investigated the blood status of 45 long-distance runners and reported that serum ferritin levels were <35 μg/L in 51% of athletes and <20 μg/L in 16%. Reinke et al. studied professional soccer players and elite rowers, finding that some athletes had normal hemoglobin levels but serum ferritin levels below the 12 μg/L cutoff. In animal studies, iron deficiency, in the absence of anemia, has been shown to reduce endurance and exercise capacity. Hinton et al. reported that prescribing iron supplements to women with normal hemoglobin and low serum ferritin levels improved exercise capacity. These results indicate that iron levels in the body may be reduced even when hemoglobin concentrations are within the normal range.

Mielgo Ayuso et al. reported that to screen for iron deficiency, 30–99 ng/mL is considered functional iron deficiency, and a serum ferritin level of at least 100 ng/mL is required. These reports suggest that a higher cutoff value of ferritin may be beneficial when screening for iron deficiency in athletes.

Exercise and iron

1. AEROBIC EXERCISE

Many human studies have reported that aerobic exercise reduces hematocrit, blood hemoglobin concentration, and serum iron levels, and weakens red blood cell membranes. Endurance athletes, particularly elite long-distance athletes, train for long periods of time on multiple occasions throughout the day. Daily training in iron deficiency conditions reduces performance. Davies et al. reported that endurance performance decreased by up to 30% in athletes with iron deficiency anemia. It is well known that factors contributing to iron deficiency anemia in athletes include hemolysis from mechanical stimulation during running, as well as sweating during training and hypertonic sweating. The possibility of increased red blood cell turnover in athletes was also supported by ferrokinetic measurements performed by Ehn et al., who showed that female athletes lost iron 20% faster than non-athletes in experiments using radioactive iron, and that iron loss was faster than in adult males. They also reported that female athletes had normal hemoglobin and plasma iron levels but a latent iron deficiency in their bone marrow.

Animal studies have shown that aerobic exercise can reduce or ameliorate the reduction in biological markers of iron caused by iron deficiency. Perkkio et al. observed that aerobic exercise (treadmill running) in iron-deficient rats significantly increased hemoglobin concentration, endurance, and VO2max relative to iron-deficient resting rats. In contrast, no decrease in hemoglobin concentration was observed in iron-sufficient rats that exercised relative to the non-exercising groups. Willis et al. also reported that aerobic exercise (treadmill running) results in significantly higher hemoglobin concentrations in iron-deficient rats than in resting rats.

2. RESISTANCE EXERCISE

There are very few studies on the effects of resistance exercise on iron metabolism in vivo in comparison to aerobic exercise. Unlike aerobic exercise, resistance exercise promotes the synthesis of somatic proteins, and the faster the nutritional intake following exercise, the higher the muscle protein synthesis.

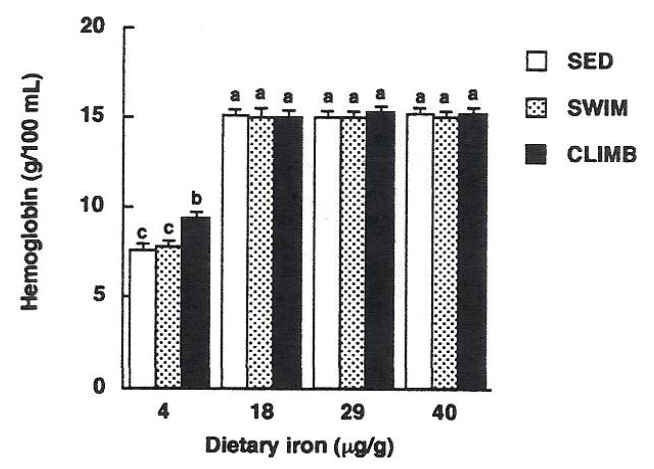

Mild resistance exercise has been reported to improve latent iron deficiency in young women without iron supplementation. Matsuo et al. reported that when women with latent iron deficiency performed resistance exercise (dumbbell exercise) for 12 weeks, there was a significant increase in serum ferritin levels, hemoglobin concentration, red blood cell count, and total iron binding capacity, and that daily mild resistance exercise improved non-anemic iron deficiency and prevented iron deficiency anemia. Additionally, Matsuo et al. found that resistance exercise alleviated iron deficiency anemia in rats that climbed a 2-meter wire tower to obtain water. This effect suggests that resistance exercise is related to an increase in ALAD activity, an enzyme involved in heme biosynthesis. Rats that habitually engaged in climbing exercises showed increased bone marrow ALAD activity after exercise. Matsuo et al. compared iron-deficient rats that had habitually engaged in climbing or swimming exercises for 8 weeks, and reported that while swimming exercise did not change bone marrow ALAD activity, climbing exercise increased ALAD activity. This result suggests that resistance exercise may increase hemoglobin concentration, unlike aerobic exercise.

Fujii et al. have also reported that voluntary resistance exercise, such as climbing, is effective in reducing iron deficiency anemia. However, it has been speculated that even if resistance exercise increases the ability to biosynthesize heme, blood hemoglobin levels may not recover if the supply of iron, the material for hemoglobin, from diet or stored iron is inadequate. Although some observations have been made on the effects of resistance exercise on iron nutrition in the body, the number of publications is significantly lower than that on aerobic exercise. Further research is needed to update the in vivo iron recycling capacity and the possibility of different iron uptakes depending on the type of exercise.

Diet

The first step in optimizing iron supplementation in athletes is to correct any existing iron deficiencies. For iron deficiency, the initial step is usually to improve dietary intake. Iron intake of 14 mg per day should be targeted. This is approximately twice the recommended amount for an average Japanese individual. Additionally, the recommended iron intake for female endurance runners is 18 mg/day, posing a significant burden for athletes.

Clenin et al suggest that iron deficiency in athletes can be treated by dietary modification, oral supplementation, or intravenous/intramuscular supplementation. Under normal conditions, macrophages efficiently recycle old red blood cells. Iron absorption from the daily diet is estimated to be approximately 15–20% for hemo iron and 5–10% for non-hemo iron, and the absorption of iron from the daily diet is thought to be approximately 10% of the ingested iron.

It is important for athletes to include meat, fish, whole grains, and green vegetables in their diets. In addition, although meat-derived proteins promote iron absorption, not all proteins have this effect (meat factor). In addition, meat intake increases non-hemo iron absorption by a factor of 2, although not all animal proteins have this effect. Lyle et al. found in a long-term study of aerobic dancers that the consumption of one meat-containing meal per day was associated with the maintenance of serum ferritin levels and reported that it was effective. Furthermore, Tetens et al. reported that serum ferritin levels are maintained in women of childbearing age who consume a meat-based diet, but that these levels are reduced in women who consume a plant-based diet. Fujii et al. reported that a protein intake of >1.0 g/kg BW/day, of which animal-derived protein was approximately 50%, resulted in no anemic individuals among athletes.

Further, foods rich in vitamin C increase iron absorption, whereas polyphenols found in coffee, tea, and certain plants inhibit iron absorption. This should be considered in the daily diets to avoid anemia.

Treatment

Most oral iron preparations are used in clinical practice. Oral iron tablets, such as ferrous iron (100-200 mg/day), ferrous fumarate (100 mg/day), and dry ferrous sulphate (105-210 mg/day), often cause gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, making it difficult to continue taking them for long periods. To manage these gastrointestinal symptoms, patients can change the time of administration from during the day to before bedtime, or use soluble ferric pyrophosphate (120-240 mg/day), which is essentially a pediatric formulation, in small doses. However, managing these symptoms in practice can be challenging.

Oral iron preparations are often avoided due to their adverse effects on intestinal lesions. Since the daily dose of intravenous iron is limited to 40–120 mg, frequent administration is necessary to ensure reliable iron supplementation. Recently, iron supplements have become common as a preventive measure against anemia, not only for athletes but also for people who do not exercise. Various supplements and products to improve iron balance are available on the market. Brigham et al. reported that a supplement containing ferrous sulfate (39 mg/day of iron) prevented a decrease in serum ferritin levels in female swimmers. Hinton et al. also reported that the administration of ferrous sulfate (36.8 mg/day iron) to late-iron-deficient women significantly increased serum ferritin levels and improved endurance exercise capacity. In addition, Kang et al. reported that supplementation of young female soccer players with iron (40 mg, per day) significantly increased serum ferritin levels and prevented hemoglobin decline. The low doses of iron used in these studies suggest that iron supplements and preparations can improve iron stores, even at low doses.

As mentioned above, the side effects of oral iron supplementation may include gastrointestinal disturbances such as nausea, abdominal pain, and constipation, which may interfere with daily performance and require careful consideration. It is also recommended that athletes monitor their iron status regularly and treat deficiencies as soon as they occur. Clarke et al. recommend hematological testing every 6 months for women and annually for men unless there are other clinical indications. However, no specific ferritin level is recommended for athletes to determine improvements in iron deficiency. Clearer guidelines for iron supplementation and the associated hepcidin response to improve exercise performance are needed. It has been reported that intravenous iron supplementation has no particular advantage over oral supplementation with respect to iron status in athletes. Few studies have used dietary approaches to iron management rather than pharmaceutical iron supplementation in athletes. Dietary iron treatment methods used in the literature include prescription of iron-rich diets and/or hemo-iron-based diets, dietary counselling, and introduction of new iron-rich products into the daily diet. The majority of studies suggest that dietary iron interventions have a beneficial effect on iron status in iron-deficient athletes. However, the direct effects on athletic performance in female athletes are unknown. Nevertheless, it has been suggested that dietary iron interventions may help maintain iron status in female athletes, particularly during periods of intense training and competition.

Conclusions

This review examined the effects of exercise on iron deficiency and provided evidence to support these findings. Exercise induces an inflammatory response. Athletes who exercise daily may develop anemia during chronic inflammation. Inflammation-induced anemia increases iron excretion and inhibits iron absorption. The iron status of athletes should be carefully monitored during training, with particular attention to conditions associated with increased iron loss or demand. Early identification of reduced iron stores and subsequent supplementation may prevent further decline in iron status.

Dietary prevention of iron deficiency anemia is a fundamental aspect of sports nutrition. However, iron is one of the most difficult minerals to consume. The recommended intake is 14 mg, which is a significant burden for athletes. It is therefore important to consider not only iron supplementation, but also an anti-inflammatory diet and the timing of intake. Just as estimated energy intake needs to be considered individually, iron intake needs to be tailored to individual sports.

1. There is therefore an urgent need to determine the appropriate ferritin concentration for athletes.

2. As with estimated energy intake, iron intake needs to be considered on an individual basis.

Acknowledgements

The authors contributed equally to this work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- Clarkson PM. Minerals: exercise performance and supplementation in athletes. J Sports Sci. 1991;9 Spec No:91-116. Doi:10.1080/02640419108729869

- Weaver CM, Rajaram S. Exercise and iron status. J Nutr. 1992;122(3 Suppl):782-787. Doi:10.1093/jn/122.suppl_3.782

- Cook JD. The effect of endurance training on iron metabolism. Semin Hematol. 1994;31(2):146-154.

- Ehn L, Carlmark B, Höglund S. Iron status in athletes involved in intense physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1980;12(1):61-64.

- Dufaux B, Hoederath A, Streitberger I, Hollmann W, Assmann G. Serum ferritin, transferrin, haptoglobin, and iron in middle- and long-distance runners, elite rowers, and professional racing cyclists. Int J Sports Med. 1981;2(1):43-46. Doi:10.1055/s-2008-1034583

- Di Santolo M, Stel G, Banfi G, Gonano F, Cauci S. Anemia and iron status in young fertile non-professional female athletes. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2008;102(6):703-709. Doi:10.1007/s00421-007-0647-9

- Muñoz Gómez M, Campos Garríguez A, García Erce JA, Ramírez Ramírez G. Fisiopatología del metabolismo del hierro: implicaciones diagnósticas y terapéuticas [Fisiopathology of iron metabolism: diagnostic and therapeutic implications]. Nefrologia. 2005;25(1):9-19.

- Andrews NC. Disorders of iron metabolism [published correction appears in N Engl J Med 2000 Feb 3;342(5):364]. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(26):1986-1995. Doi:10.1056/NEJM199912233412607

- Siah CW, Ombiga J, Adams LA, Trinder D, Olynyk JK. Normal iron metabolism and the pathophysiology of iron overload disorders. Clin Biochem Rev. 2006;27(1):5-16.

- Fleming RE, Bacon BR. Orchestration of iron homeostasis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(17):1741-1744. Doi:10.1056/NEJMp048363

- Ganz T. Hepcidin, a key regulator of iron metabolism and mediator of anemia of inflammation. Blood. 2003;102(3):783-788. Doi:10.1182/blood-2003-03-0672

- Lee PL, Beutler E. Regulation of hepcidin and iron-overload disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009;4:489-515. Doi:10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092205

- Nemeth E, Ganz T. Hepcidin and Iron in Health and Disease. Annu Rev Med. 2023;74:261-277. Doi:10.1146/annurev-med-043021-032816

- Bloomer SA, Brown KE. Hepcidin and Iron Metabolism in Experimental Liver Injury. Am J Pathol. 2021;191(7):1165-1179. Doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2021.04.005

- Gunshin H, Mackenzie B, Berger UV, et al. Cloning and characterization of a mammalian proton-coupled metal-ion transporter. Nature. 1997;388(6641):482-488. Doi:10.1038/41343

- Shayeghi M, Latunde-Dada GO, Oakhill JS, et al. Identification of an intestinal heme transporter. Cell. 2005;122(5):789-801. Doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.025

- Hentze MW, Muckenthaler MU, Galy B, Camaschella C. Two to tango: regulation of Mammalian iron metabolism. Cell. 2010;142(1):24-38. Doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.028

- Raffin SB, Woo CH, Roost KT, Price DC, Schmid R. Intestinal absorption of hemoglobin iron-heme cleavage by mucosal heme oxygenase. J Clin Invest. 1974;54(6):1344-1352. Doi:10.1172/JCI107881

- Abboud S, Haile DJ. A novel mammalian iron-regulated protein involved in intracellular iron metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(26):19906-19912. Doi:10.1074/jbc.M000713200

- Donovan A, Brownlie A, Zhou Y, et al. Positional cloning of zebrafish ferroportin1 identifies a conserved vertebrate iron exporter. Nature. 2000;403(6771):776-781. Doi:10.1038/35001596

- McKie AT, Marciani P, Rolfs A, et al. A novel duodenal iron-regulated transporter, IREG1, implicated in the basolateral transfer of iron to the circulation. Mol Cell. 2000;5(2):299-309. Doi:10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80425-6

- Vulpe CD, Kuo YM, Murphy TL, et al. Hephaestin, a ceruloplasmin homologue implicated in intestinal iron transport, is defective in the sla mouse. Nat Genet. 1999;21(2):195-199. Doi:10.1038/5979

- Harris ZL, Durley AP, Man TK, Gitlin JD. Targeted gene disruption reveals an essential role for ceruloplasmin in cellular iron efflux. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(19):10812-10817. Doi:10.1073/pnas.96.19.10812

- Roetto A, Mezzanotte M, Pellegrino RM. The Functional Versatility of Transferrin Receptor 2 and Its Therapeutic Value. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2018;11(4):115. Published 2018 Oct 23. Doi:10.3390/ph11040115

- Aisen P. Transferrin receptor 1. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36(11):2137-2143. Doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2004.02.007

- Stewart JG, Ahlquist DA, McGill DB, Ilstrup DM, Schwartz S, Owen RA. Gastrointestinal blood loss and anemia in runners. Ann Intern Med. 1984;100(6):843-845. Doi:10.7326/0003-4819-100-6-843

- Beard J, Tobin B. Iron status and exercise. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72(2 Suppl):594S-7S. Doi:10.1093/ajcn/72.2.594S

- Lukaski HC. Vitamin and mineral status: effects on physical performance. Nutrition. 2004;20(7-8):632-644. Doi:10.1016/j.nut.2004.04.001

- Celsing F, Ekblom B. Anemia causes a relative decrease in blood lactate concentration during exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1986;55(1):74-78. Doi:10.1007/BF00422897

- Miller BJ, Pate RR, Burgess W. Foot impact force and intravascular hemolysis during distance running. Int J Sports Med. 1988;9(1):56-60. Doi:10.1055/s-2007-1024979

- King N, Fridlund KE, Askew EW. Nutrition issues of military women. J Am Coll Nutr. 1993;12(4):344-348. Doi:10.1080/07315724.1993.10718320

- Brune M, Magnusson B, Persson H, Hallberg L. Iron losses in sweat. Am J Clin Nutr. 1986;43(3):438-443. Doi:10.1093/ajcn/43.3.438

- Cappellini MD, Musallam KM, Taher AT. Iron deficiency anaemia revisited. J Intern Med. 2020;287(2):153-170. Doi:10.1111/joim.13004

- Nemeth E, Tuttle MS, Powelson J, et al. Hepcidin regulates cellular iron efflux by binding to ferroportin and inducing its internalization. Science. 2004;306(5704):2090-2093. Doi:10.1126/science.1104742

- Nemeth E, Ganz T. Hepcidin-Ferroportin Interaction Controls Systemic Iron Homeostasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(12):6493. Published 2021 Jun 17. Doi:10.3390/ijms22126493

- Badenhorst CE, Dawson B, Cox GR, Laarakkers CM, Swinkels DW, Peeling P. Acute dietary carbohydrate manipulation and the subsequent inflammatory and hepcidin responses to exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2015;115(12):2521-2530. Doi:10.1007/s00421-015-3252-3

- WHO 2024. Prevalence of anemia in women of reproductive age (aged 15–49) (%). Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/prevalence-of-anaemia-in-women-of-reproductive-age-(15-49)

- Galetti V, Stoffel NU, Sieber C, Zeder C, Moretti D, Zimmermann MB. Threshold ferritin and hepcidin concentrations indicating early iron deficiency in young women based on upregulation of iron absorption. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;39:101052. Published 2021 Jul 31. Doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101052

- Nachtigall D, Nielsen P, Fischer R, Engelhardt R, Gabbe EE. Iron deficiency in distance runners. A reinvestigation using Fe-labelling and non-invasive liver iron quantification. Int J Sports Med. 1996;17(7):473-479. Doi:10.1055/s-2007-972881

- Reinke S, Taylor WR, Duda GN, et al. Absolute and functional iron deficiency in professional athletes during training and recovery. Int J Cardiol. 2012;156(2):186-191. Doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.10.139

- Hinton PS. Iron and the endurance athlete. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2014;39(9):1012-1018. Doi:10.1139/apnm-2014-0147

- Mielgo-Ayuso J, Zourdos MC, Calleja-González J, Córdova A, Fernandez-Lázaro D, Caballero-García A. Eleven Weeks of Iron Supplementation Does Not Maintain Iron Status for an Entire Competitive Season in Elite Female Volleyball Players: A Follow-Up Study. Nutrients. 2018;10(10):1526. Published 2018 Oct 17. Doi:10.3390/nu10101526

- Ganz T, Nemeth E. Iron metabolism: interactions with normal and disordered erythropoiesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(5):a011668. Doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a011668

- Varga E, Pap R, Jánosa G, Sipos K, Pandur E. IL-6 Regulates Hepcidin Expression Via the BMP/SMAD Pathway by Altering BMP6, TMPRSS6 and TfR2 Expressions at Normal and Inflammatory Conditions in BV2 Microglia. Neurochem Res. 2021;46(5):1224-1238. Doi:10.1007/s11064-021-03322-0

- Dressendorfer RH, Wade CE, Amsterdam EA. Development of pseudoanemia in marathon runners during a 20-day road race. JAMA. 1981;246(11):1215-1218.

- Davies KJ, Maguire JJ, Brooks GA, Dallman PR, Packer L. Muscle mitochondrial bioenergetics, oxygen supply, and work capacity during dietary iron deficiency and repletion. Am J Physiol. 1982;242(6):E418-E427. Doi:10.1152/ajpendo.1982.242.6.E418

- Dufaux B, Hoederath A, Streitberger I, Hollmann W, Assmann G. Serum ferritin, transferrin, haptoglobin, and iron in middle- and long-distance runners, elite rowers, and professional racing cyclists. Int J Sports Med. 1981;2(1):43-46. Doi:10.1055/s-2008-1034583

- Brune M, Magnusson B, Persson H, Hallberg L. Iron losses in sweat. Am J Clin Nutr. 1986;43(3):438-443. Doi:10.1093/ajcn/43.3.438

- Clarkson PM. Minerals: exercise performance and supplementation in athletes. J Sports Sci. 1991;9 Spec No:91-116. Doi:10.1080/02640419108729869

- Ehn L, Carlmark B, Höglund S. Iron status in athletes involved in intense physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1980;12(1):61-64.

- de Wijn JF, de Jongste JL, Mosterd W, Willebrand D. Hemoglobin, packed cell volume, serum iron and iron binding capacity of selected athletes during training. Nutr Metab. 1971;13(3):129-139. Doi:10.1159/000175330

- Risser WL, Lee EJ, Poindexter HB, et al. Iron deficiency in female athletes: its prevalence and impact on performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1988;20(2):116-121. Doi:10.1249/00005768-198820020-00003

- Tobin BW, Beard JL. Interactions of iron deficiency and exercise training in male Sprague-Dawley rats: ferrokinetics and hematology. J Nutr. 1989;119(9):1340-1347. Doi:10.1093/jn/119.9.1340

- Perkkiö MV, Jansson LT, Henderson S, Refino C, Brooks GA, Dallman PR. Work performance in the iron-deficient rat: improved endurance with exercise training. Am J Physiol. 1985;249(3 Pt 1):E306-E311. Doi:10.1152/ajpendo.1985.249.3.E306

- Radomski MW, Sabiston BH, Isoard P. Development of “sports anemia” in physically fit men after daily sustained submaximal exercise. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1980;51(1):41-45.

- Willis WT, Brooks GA, Henderson SA, Dallman PR. Effects of iron deficiency and training on mitochondrial enzymes in skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1987;62(6):2442-2446. Doi:10.1152/jappl.1987.62.6.2442

- Yang RC, Mack GW, Wolfe RR, Nadel ER. Albumin synthesis after intense intermittent exercise in human subjects. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1998;84(2):584-592. Doi:10.1152/jappl.1998.84.2.584

- Okamura K, Doi T, Hamada K, et al. Effect of amino acid and glucose administration during postexercise recovery on protein kinetics in dogs. Am J Physiol. 1997;272(6 Pt 1):E1023-E1030. Doi:10.1152/ajpendo.1997.272.6.E1023

- Esmark B, Andersen JL, Olsen S, Richter EA, Mizuno M, Kjaer M. Timing of postexercise protein intake is important for muscle hypertrophy with resistance training in elderly humans. J Physiol. 2001;535(Pt 1):301-311. Doi:10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00301.x

- Levenhagen DK, Gresham JD, Carlson MG, Maron DJ, Borel MJ, Flakoll PJ. Postexercise nutrient intake timing in humans is critical to recovery of leg glucose and protein homeostasis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;280(6):E982-E993. Doi:10.1152/ajpendo.2001.280.6.E982

- Matsuo, T.; Suzuki, H.; Suzuki, M. Dubbell exercise improves non-anemic iron deficiency in young women without iron supplementation. Health Sci 2000. 16:236-243.

- Matsuo, T.; Suzuki, H.; Suzuki, M. 2000. Resistance Exercise Increases the Capacity of Heme Biosynthesis More Than Aerobic Exercise in Rats. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2000 29:19-27.

- Matsuo T, Kang HS, Suzuki H, Suzuki M. Voluntary resistance exercise improves blood hemoglobin concentration in severely iron-deficient rats. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2002;48(2):161-164. Doi:10.3177/jnsv.48.161

- Fujii T, Asai T, Matsuo T, Okamura K. Effect of resistance exercise on iron status in moderately iron-deficient rats. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2011;144(1-3):983-991. Doi:10.1007/s12011-011-9072-3

- Fujii T, Matsuo T, Okamura K. Effects of resistance exercise on iron absorption and balance in iron-deficient rats. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2014;161(1):101-106. Doi:10.1007/s12011-014-0075-8

- Dietary reference values for food energy and nutrients for the United Kingdom. Report of the Panel on Dietary Reference Values of the Committee on Medical Aspects of Food Policy. Rep Health Soc Subj (Lond). 1991;41:1-210.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Panel on Micronutrients. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001.

- Clénin G, Cordes M, Huber A, et al. Iron deficiency in sports – definition, influence on performance and therapy. Swiss Med Wkly. 2015;145:w14196. Published 2015 Oct 29. Doi:10.4414/smw.2015.14196

- Meehye K, Dong-Tae L, Yeon-Sook L. Iron absorption and intestinal solubility in rats are influenced by dietary proteins. Nutrition Research 1995.15: 1705-1716. https://doi.org/10.1016/0271-5317(95)02041-0

- Lyle RM, Weaver CM, Sedlock DA, Rajaram S, Martin B, Melby CL. Iron status in exercising women: the effect of oral iron therapy vs increased consumption of muscle foods. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;56(6):1049-1055. Doi:10.1093/ajcn/56.6.1049

- Tetens I, Bendtsen KM, Henriksen M, Ersbøll AK, Milman N. The impact of a meat- versus a vegetable-based diet on iron status in women of childbearing age with small iron stores. Eur J Nutr. 2007;46(8):439-445. Doi:10.1007/s00394-007-0683-6

- Fujii, T., Okumura, Y., Maeshima, E., Okamura, K. Dietary Iron Intake and Hemoglobin Concentration in College Athletes in Different Sports. Int J Sports Exerc Med. 2015 1:5. Doi: 10.23937/2469-5718/1510029

- Solberg A, Reikvam H. Iron Status and Physical Performance in Athletes. Life (Basel). 2023;13(10):2007. Published 2023 Oct 2. Doi:10.3390/life13102007

- McKay AKA, Pyne DB, Burke LM, Peeling P. Iron Metabolism: Interactions with Energy and Carbohydrate Availability. Nutrients. 2020;12(12):3692. Published 2020 Nov 30. Doi:10.3390/nu12123692

- Brigham DE, Beard JL, Krimmel RS, Kenney WL. Changes in iron status during competitive season in female collegiate swimmers. Nutrition. 1993;9(5):418-422.

- Kang HS, Matsuo T. Effects of 4 weeks iron supplementation on haematological and immunological status in elite female soccer players. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2004;13(4):353-358.

- Garvican-Lewis LA, Vuong VL, Govus AD, et al. Intravenous Iron Does Not Augment the Hemoglobin Mass Response to Simulated Hypoxia. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2018;50(8):1669-1678. Doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000001608

- Friedrisch JR, Cançado RD. Intravenous ferric carboxymaltose for the treatment of iron deficiency anemia. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter. 2015;37(6):400-405. Doi:10.1016/j.bjhh.2015.08.012

- Clarke AC, Anson JM, Dziedzic CE, Mcdonald WA, Pyne DB. Iron monitoring of male and female rugby sevens players over an international season. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2018;58(10):1490-1496. Doi:10.23736/S0022-4707.17.07363-7

- Fujii T, Kobayashi K, Kaneko M, Osana S, Tsai CT, Ito S, Hata. RGM Family Involved in the Regulation of Hepcidin Expression in Anemia of Chronic Disease. Immuno 2024, 4(3), 266-285. https://doi.org/10.3390/immuno4030017

- Ems, T.; St Lucia, K.; Huecker, M.R. Biochemistry, Iron Absorption. In StatPearls; Ineligible Companies: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13102007

- Tsalis G, Nikolaidis MG, Mougios V. Effects of iron intake through food or supplement on iron status and performance of healthy adolescent swimmers during a training season. Int J Sports Med. 2004;25(4):306-313. Doi:10.1055/s-2003-45250

- Ishizaki S, Koshimizu T, Yanagisawa K, et al. Effects of a fixed dietary intake on changes in red blood cell delta-aminolevulinate dehydratase activity and hemolysis. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2006;16(6):597-610. Doi:10.1123/ijsnem.16.6.597

- Burke DE, Johnson JV, Vukovich MD, Kattelmann KK. Effects of lean beef supplementation on iron status, body composition and performance of collegiate distance runners. Food Nutr Sci. 2012. 3:810–21. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/fns.2012.36109

- Anschuetz S, Rodgers CD, Taylor AW. Meal composition and iron status of experienced male and female distance runners. J Exerc Sci Fit. 2010. 8:25–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1728-869X(10)60004-4

- Alaunyte I, Stojceska V, Plunkett A, Derbyshire E. Dietary iron intervention using a staple food product for improvement of iron status in female runners. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2014;11(1):50. Published 2014 Oct 18. Doi:10.1186/s12970-014-0050-y

- Burke DE, Johnson JV, Vukovich MD, Kattelmann KK. 2012. Effects of lean beef supplementation on iron status, body composition and performance of collegiate distance runners. Food Nutr Sci. 3:810–21. Doi: 10.4236/fns.2012.36109