Optimizing Inspiratory Muscle Training: The BREATHS Framework

BREATHS: A Knowledge Translation Framework for Optimizing Inspiratory Muscle Training in Physical Therapy Practice

Jennifer Anderson1, PT, DPT; Deborah Priluck2, PT, DPT; Konrad J. Dias3, PT, DPT, PhD

- Jennifer Anderson, PT, DPT American Physical Therapy Association Board Certified Specialist in Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Physical Therapy. Assistant Professor of Physical Therapy and Athletic Training, Saint Louis University Program in Physical Therapy. 3437 Caroline Street Suite 1026, St. Louis, MO 63104

- Deborah Priluck, PT, DPT American Physical Therapy Association Board Certified Specialist in Neurologic Physical Therapy. Assistant Professor of Physical Therapy. Washington University Program in Physical Therapy. 4444 Forest Park Ave Suite 1101. St. Louis, MO 63110.

- Konrad J. Dias, PT, DPT, PhD Professor of Physical Therapy, Department of Physical Therapy, College of Health and Human Services, California State University, Sacramento. 6000 J Street, Sacramento CA 95819

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 30 June 2025

CITATION: ANDERSON, Jennifer; PRILUCK, Deborah; DIAS, Konrad J.. BREATHS: A Knowledge Translation Framework for Optimizing Inspiratory Muscle Training in Physical Therapy Practice. Medical Research Archives, [S.l.], v. 13, n. 6, june 2025. ISSN 2375-1924. Available at: <https://esmed.org/MRA/mra/article/view/6591>.

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i6.6591

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

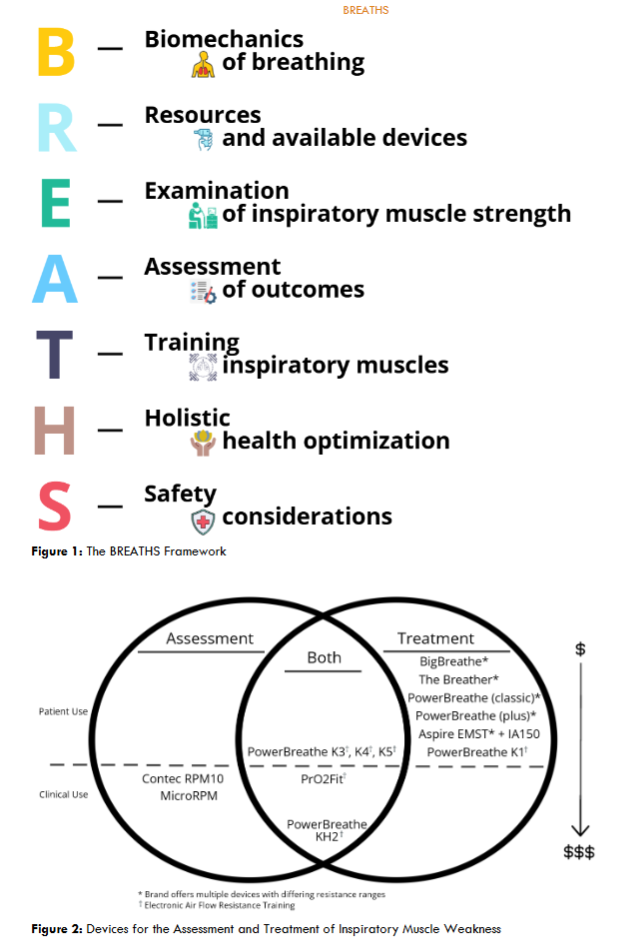

There is an overwhelming body of evidence that supports the efficacy of inspiratory muscle training in improving strength of the inspiratory muscles and activity performance in a variety of patient populations. Essential to the utilization of this abundant body of evidence is knowledge translation, a concept that emphasizes the translation of global knowledge to application that can be effectively integrated into clinical practice. To this effect, this perspective paper aims to provide physical therapists with explicit ways to apply and integrate the evidence related to inspiratory muscle training into clinical practice by proposing a novel 7-step BREATHS framework. This framework discusses the Biomechanics of breathing, Resources and devices available for inspiratory muscle assessment and treatment, Examination of inspiratory muscle strength, Assessment of outcome measures, Treatment considerations in strengthening inspiratory muscles, Holistic health impact through inspiratory muscle training, and Safety considerations for clinicians to consider across the continuum of care. This framework is designed to upskill physical therapists and other health care providers with a contemporary model to deliver safe, effective, and evidence-informed inspiratory muscle training for various patients and clients. The paper elucidates the underpinnings of each aspect of the BREATHS framework and its application to practice, enabling clinicians to better appreciate the power of inspiratory muscle training in maximizing overall health and wellness in their patients and clients.

Keywords

Inspiratory muscle training, physical therapy, knowledge translation, BREATHS framework, patient care

Introduction

The vision statement of the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) defines the need for physical therapists to transform society by optimizing movement to improve the human experience. In order to optimize movement, the APTA has created and promoted the movement system which is defined as the collection of the nervous, endocrine, musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, pulmonary, and integumentary systems that interact as integral components that affect human movement. Optimal movement requires the inspiratory muscles to work effectively to bring in oxygen and sustain activity. A known but often underestimated reason for overall movement dysfunction is breathlessness and exercise intolerance that stems from inspiratory muscle weakness. To this effect, this review article delineates a novel 7-step BREATHS framework (Figure 1) or implementing inspiratory muscle assessment and training as a component of routine clinical practice. The BREATHS framework encapsulates an evidence-based review of the literature related to the Biomechanics of breathing, Resources available for strengthening inspiratory muscles, Examination of inspiratory muscle strength, Assessment of outcomes, Treatment considerations for training inspiratory muscles, Holistic health, and Safety considerations. It is essential for physical therapists to utilize best practice when caring for patients and clients that present with breathlessness and exercise intolerance. In several populations of patients, including patients with chronic non-communicable diseases such as heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease and others, respiratory muscle function is often compromised. The BREATHS framework has clinical utility in any setting within the continuum of care. It reviews key proficiencies related to the examination, assessment and treatment of inspiratory muscle function. An appreciation of each of the components of the BREATHS framework in clinical practice collectively sets the stage for a comprehensive approach to strengthening the inspiratory muscles. Several systematic reviews and metanalysis showcase the benefits of inspiratory muscle training (IMT) in improving function in a variety of patient populations. However, no manuscript or evidence-based resource currently exists that explicitly formulates a systematic approach on how physical therapists can translate this knowledge into practice in an effort to strengthen the inspiratory muscles. Therefore, the purpose of this perspective paper is to translate current empirical evidence into the BREATHS framework to support physical therapists in implementing inspiratory muscle strength training.

Methodology

In this review article, author commentary is based on selected articles that have been recently published that highlight considerations related to the biomechanics of breathing, assessment of inspiratory muscle strength, assessment of functional outcomes, and dosage of treatment interventions for strengthening inspiratory muscles. The search strategy focused on contemporary research related to IMT conducted in large groups of patient populations across a variety of age ranges and diagnoses. Additionally, articles that exclusively investigated inspiratory training and not expiratory muscle training were chosen for the purposes of this paper. Further, articles that incorporated various outcome measures that assessed holistic health improvements were selected to provide the reader with a comprehensive understanding of the value of strengthening inspiratory muscles. Finally, guidance for the examination of inspiratory muscle strength was sought from a scientific statement provided by the European Respiratory Society. Commentary within this paper focuses on the ways physical therapists can integrate the knowledge related to the examination and treatment of inspiratory muscles within clinical practice. Authors specifically identify areas of consideration and cite selected articles related to each aspect of the BREATHS framework. This article is not a systematic review or scoping review and so the authors make no claims that the selection of articles is free from bias. The authors simply put forward thoughts for reasonable consideration that can be used in clinical practice.

The Breaths Framework

Biomechanics of Breathing

In order to appreciate the importance of inspiratory muscle strength, clinicians must first consider the biomechanics involved in breathing. Ventilation or breathing combines the processes of inspiration and expiration. Inspiration, or the movement of air into the lungs, is an active process that requires muscles to contract to create changes in volume and pressure within the thorax. The muscles engaged in inspiration must contract with adequate force to enlarge the volume of the thoracic cavity and lungs. The increased volume created through contraction of the inspiratory muscles reduces intrathoracic and intrapulmonary pressures allowing gases to move from the atmosphere into the lungs. Additionally, the inspiratory muscles are required to contract adequately to overcome any resistance in the airways as well as external gravitational forces, both of which vary based on body position, and the elastic recoil forces of the lungs. Alternatively, expiration is primarily a passive process, driven by the elastic recoil of the lungs. During passive expiration, the inspiratory muscles relax and thoracic structures return to their resting position, reversing the pressure gradient and causing air to flow out of the lungs.

Two primary muscles of inspiration include the diaphragm and external intercostals. Additionally, inspiration is also supported by contraction of various accessory muscles, which include any muscle that attaches to the thoracic spine, sternum, ribs, or shoulder complex. All these muscles collectively work to increase the volume of the thoracic cavity. The muscles of inspiration are skeletal muscles and therefore are susceptible to weakness and dysfunction. In patients presenting with exercise intolerance, inspiratory muscle weakness may be a key contributor to dysfunction of the movement system and the associated symptoms of dyspnea that the patient experiences during exercise. For this reason, an evaluation of inspiratory muscle strength along with treatment of inspiratory muscle weakness are important considerations in the management of breathlessness related exercise intolerance.

Respiratory muscle weakness can be assessed, directly or indirectly, using a variety of techniques that measure respiratory pressures, volumes, flow rates, and excursion of the chest wall or diaphragm. The most commonly reported and straightforward measurement of inspiratory muscle strength uses a pressure manometer to gauge the amount of force generated during maximal effort inspiration, referred to as maximal inspiratory pressure (MIP) and typically expressed in units of centimetres of water pressure (cm H2O). Maximal inspiratory pressure is a static measurement of global inspiratory force that reflects the work of all inspiratory muscles. This measure provides an accurate assessment of the overall strength of the inspiratory muscles and is unable to isolate and differentiate strength between individual respiratory muscles.

When thinking about MIP, clinicians must recognize that the amount of inspiratory pressure required for normal quiet breathing represents only a small fraction of MIP. In other words, during quiet resting breathing healthy respiratory muscles work minimally to generate a pressure that triggers inspiration. This pressure generated by inspiratory muscle contraction is substantially less than the MIP. For this reason, healthy respiratory muscles are highly resistant to fatigue and can sustain a normal minute ventilation with minimal effort. However, in individuals with inspiratory muscle weakness, the inspiratory muscles exert a pressure that is relatively at a higher percentage of the MIP to facilitate breathing at rest. For this reason, clinicians will find that the weaker the inspiratory muscles, the higher the work of breathing and subjective effort. The work of breathing is compounded further by conditions where inspiratory muscles must overcome excessive airway resistance or poor compliance of the lungs or chest wall. In these situations, inspiratory muscles are forced to work at even higher proportions of their maximal force-generating capacity or MIP to facilitate breathing. Further, inspiratory muscles do not just contribute to the act of breathing, but are engaged in functions like speech, coughing, bowel and bladder control, postural control, and maintaining trunk stability during movements of the extremities. An individual who is contracting inspiratory muscles at near-maximal effort to maintain breathing at rest cannot rely on those same muscles to simultaneously support talking or maintain posture and balance. It is for this reason that the assessment and treatment of inspiratory muscle weakness should be routinely incorporated into clinical practice to improve overall activity and participation in patients and clients.

Resources and Available Devices

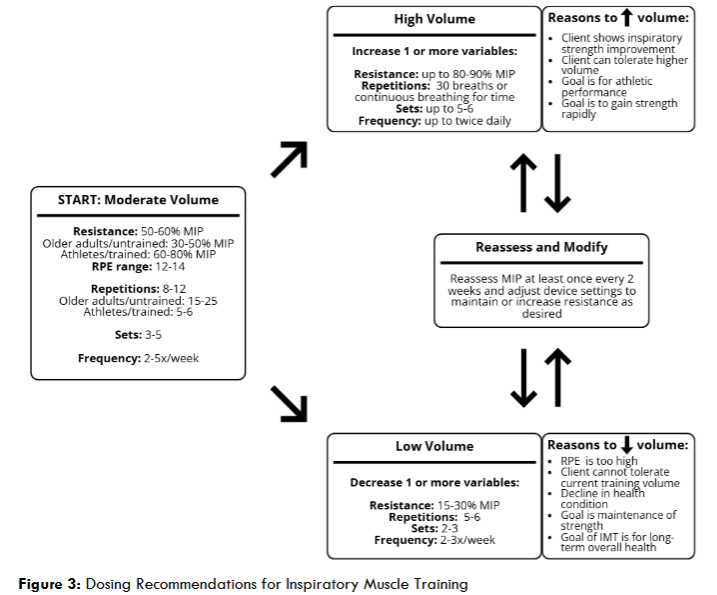

This section will review devices that are currently available for the examination of inspiratory muscle strength and treatment of inspiratory muscle weakness. Several different types of devices are currently available on the market. Some devices are designed to exclusively assess the strength of the inspiratory muscles, while others allow for an added benefit of strengthening inspiratory muscles in addition to the examination of strength. Further, some devices available on the market are manufactured for use by a single user, while others can be used by multiple clients within a clinical setting. Multi-user devices work either in conjunction with an added filter or require sanitization between users.

As indicated in the figure, the Contec RPM10 and MicroRPM are two multi-user devices that are primarily used for the assessment of inspiratory muscle strength. The Contec RPM10 does not require filters and can be used by multiple users with appropriate sanitization procedures employed between users. Alternatively, the MicroRPM inspiratory muscle strength assessment device is compatible with single use filters, thereby shortening the time for additional sanitization between users.

Several devices, as noted in the figure, provide users with the ability for both assessment and treatment of inspiratory muscle weakness. The PrO2Fit, and PowerBreathe KH2 are two devices that can be used in a clinical setting. These devices can be used by multiple patients and require disposable filters for each individual patient that uses the device. Other devices such as the PowerBreathe K3, K4, and K5 series are devices that allow for inspiratory muscle strength assessment and treatment by single patients. Additionally, the PrO2Fit and all PowerBreathe K series devices are examples of electronic devices which are relatively more expensive. Lastly, certain devices are made exclusively for the purpose of strengthening inspiratory muscles. Each of these devices are for single patient use and can be utilized by patients and clients across the continuum of care. These devices include Big Breathe, The Breather, PowerBreathe (Classic and Plus), Aspire EMST with the inspiratory adaptor, and PowerBreathe K1. The Big Breathe, Breather, PowerBreathe (Classic and Plus) and Aspire EMST with the inspiratory adaptor are all examples of manual inspiratory muscle trainers. A further discussion with more specifics on the differences between manual treatment devices and their clinical utility is delineated later in the manuscript.

Examination of Inspiratory Muscle Strength

The strength of the inspiratory muscles can be assessed by using multi-user manometers or single user devices. A feasible and accurate method for examining the strength of the inspiratory muscles in clinical practice involves measurement of the MIP by using a pressure manometer. Within any clinical setting, clinicians can use a multi-user device such as the Contec RPM10 or MicroRPM to easily measure the patient’s MIP. When using either of these devices, the clinician can obtain an objective value of the strength of the inspiratory muscles by recording the MIP during an inspiratory maneuver. This approach is analogous to a clinician using a handheld dynamometer to measure the strength of a peripheral skeletal muscle by recording the force produced during muscle contraction.

To assess MIP, the subject is instructed to complete a maximal inspiratory breath through the pressure manometer by beginning the inspiratory breath from residual volume or full expiration. Typically, the subject is first instructed to complete a full exhalation to get to their residual volume, after which the subject places a mouthpiece into their mouth and inhales as forcefully and quickly as possible until they reach full inspiration. The pressure manometer has an occluded airway, allowing the device to measure the maximal force the subject generates during the inspiratory maneuver. It is best practice to have the subject complete at least three repetitions of maximal inspiration through the device. The MIP is determined by averaging the results of three trials, when there is less than 20% difference in value between each of the trials. It is not uncommon for subjects to require an additional 1-2 preliminary trials using the device to enhance their understanding on how to properly perform the assessment. However, in instances where patients have significant inspiratory muscle weakness, additional trials may contribute to poorer performance that result from muscle fatigue. For this reason, clinicians must be vigilant in observing for reductions in scores and provide the patient with adequate rest and recovery between trials to ensure that the inspiratory muscles are not fatiguing with each subsequent trial.

The preferred testing protocol for assessment of the MIP is to have the subject seated in the upright position. It is important to note that ventilation or breathing, is a three-dimensional process with a variety of inspiratory muscles contracting to fulfill a maximal inspiratory maneuver. For this reason, the subject’s position is important to consider in inspiratory muscle strength assessment, as the position of the client will change the impact of gravity on the different muscles contracting during inspiration and there are times when it might be clinically important to assess MIP in an alternative position. Additionally, a nose clip is typically donned to ensure all inspiration occurs through the mouthpiece and against the occluded airway. For some patients, a flanged mouthpiece may be easier to use and can help to prevent air leaks. It is important to note that testing can be performed with or without a nose clip and with either a round or flanged mouthpiece, depending on the subject’s mouth control. The goal for assessment of the MIP is to ensure that the subject offers maximal inspiratory effort with all air moving through the mouth and not the nose.

When working with patients where a pressure manometer is unavailable, the clinician can seek to determine the patient’s MIP by using a variety of less expensive single user respiratory muscle trainers. The PowerBreathe K3, K4, K5, and PrO2Fit devices allow a single user to complete a maximal inspiratory breath to assess the MIP prior to beginning submaximal training with the same device. In order to approximate the MIP with a single user inspiratory muscle threshold training device, the subject is first positioned in sitting. The threshold device should be initially set at a low resistance setting. The subject is then instructed to complete a full exhalation to achieve residual volume, place the mouthpiece of the device into their mouth and inhale forcefully and quickly until they reach full inspiration. If the subject is able to obtain full inspiration with the device at the set resistance, then the resistance should be increased incrementally and the process repeated until the subject can no longer generate a breath against the device. The clinician records the resistance offered by the device immediately prior to the point of failure as an estimate of the MIP.

In addition to measuring or estimating MIP, clinicians also have the ability to predict a patient’s MIP based on reference equations. These reference equations provide a prediction of the MIP by using the age, sex, and body mass index (BMI) of the individual. Lista-Paz et al. has established the following equations to predict maximal inspiratory pressure in healthy adults.

- MIP (females) = 61.48+0.66*age+1.55*BMI-0.01*age2; R2 adjusted = 0.119

- MIP (males) = 98.60+1.18*age+0.76*BMI-0.02*age2; R2 adjusted = 0.148

Finally, utilization of normative data aids in the clinical interpretation of the individual’s inspiratory muscle strength results.

Table 1: Normative Inspiratory Strength Values and Threshold Values for Inspiratory Muscle Weakness

| Age | Mean MIP (cmH2O) Men | Mean MIP (cmH2O) Women | |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 40 | Normative Range 116 – 140 | 85 – 10 | |

| IM Weakness 63 | 58 | ||

| 40 – 60 | Normative Range 99 – 118 | 75 – 107 | |

| IM Weakness 55 | 50 | ||

| 60 – 80 | Normative Range 66 – 101 | 58 – 83 | |

| IM Weakness 47 | 43 | ||

| > 80 | Normative Range – – | IM Weakness 42 | 38 |

Assessment of Outcomes

A review of the literature related to IMT reveals widespread benefits of IMT spanning across diverse patient populations and over a wide range of outcome measures. As previously mentioned in the methodology section, this article does not serve as a scoping review or systematic review and therefore only showcases a small sampling of the research available on IMT. Table 2 highlights relevant research investigations that have explored the efficacy of IMT in various populations of individuals. Notably, the table portrays the dose of IMT used for each population and the positive effect of the intervention on various outcome measures for that population.

Across these different investigations, improvements were noted in all domains of the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning Health and Disability model. Within the domain of body structure and function, improvements were noted in measures of back pain in patients with chronic low back pain, forced vital capacity test measurements in several populations, and blood pressure measurements in people with elevated blood pressures. More specifically, with reference to improvements in MIP, the evidence supports the efficacy of IMT in improving MIP scores in women with stress incontinence, college runners, older adults with hypertension, adults with obstructive lung disease, heart failure, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, adults with cerebral palsy, adults post stroke, individuals with spinal cord injury, and adults with cancer. Additionally, improvements including six-minute walk distance, peak oxygen uptake results, and improved functional mobility in individuals post stroke were noted within the activity domain. Further, measures of participation including a variety of quality-of-life measures, depression scores, and stress urinary incontinence severity in women have been all shown to positively improve with IMT.

Table 2: Assessment of Outcomes with Inspiratory Muscle Training

| Authors | Patient Population | Setting | Intervention | Improved Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abidi et al (2024) | Women with stress urinary incontinence | Outpatient | 5 sets of 5 breaths; 3d/wk; 12wks; 30% MIP; progressive increase to 50% MIP | Stress UI severity; QOL; TUG; 6MWT; ISWT; MIP; MEP |

| Chang et al (2020)* | College 800m track runners | Outpatient | 30 breaths; 2x/day; 5d/wk; 4wks; 50% MIP; progressing by 10% weekly | 800m distance; Limb blood flow using impedance plethysmography; MIP |

| Ahmadnezhad, Yalfani, and Borujeni (2020) | Weightlifting athletes with chronic low back pain (>6 months) | Outpatient | 30 breaths; 2x/day; daily; 8wks; 50% MIP; progressing 5% per week up to 90% MIP | Pain; Transverse abdominus muscle activation; FVC; FEV1 |

| Abodonya et al (2021) | Adults with Covid-19 respiratory failure, weaned from MV | Acute/critical care | 5 min; 2x/day; 5d/wk; 2wks; 50% MIP | QOL; 6MWT; Dyspnea severity index; FVC; FEV1 |

| Palau et al (2022) | Individuals with post-covid | Outpatient | 20 mins; 2x/day; daily; 12wks; 25-30% MIP, adjusted weekly | QOL, particularly for anxiety and depression dimensions; peak VO2 |

| Craighead et al (2021)* | Adults aged 50-79 with hypertension (SBP >120) | Outpatient | 5 sets of 6 breaths; 6d/wk; 6wks; 55% MIP; progressive increase to 75% MIP | SBP; DBP (slight); BP changes sustained 6wks after treatment; MIP |

| Charususin et al (2018)* | Adults with COPD with inspiratory muscle weakness | Outpatient pulmonary rehab | 20 min; daily; 12wks; 50% MIP; increased load as able | Endurance cycling time; Dyspnea at isotime on cycle test; FVC; MIP |

| Bosnak-Guclu et al (2011) | Adults with stable HFrEF (NYHA Class II and III) | Outpatient | 30 min; daily; 6wks; 40% MIP; adjusted weekly to maintain MIP | BBS; 6MWT; Dyspnea (mMRC); Depression (MADRS); Quadriceps femoris isometric strength; MIP; MEP |

| Huang et al (2020) | Adults with multiple sclerosis (EDSS ≥ 6.5) | Long term care facility | 3 sets of 15 breaths; daily; 10wks; 30% MIP; adjusted weekly to maintain MIP | MIP; MEP; improvements after 5wks, additional improvements after 10wks |

| Martin-Sanchez et al (2024) | Adults with cerebral palsy | Institution | 10 sets of 1 min training, 1 min rest; 5d/wk; 8wks; 40% MIP | FEV1; PEF; MIP; MEP |

| Dogan et al (2024) | Adults with chronic stroke (≥ 3 months) | IRF | 15 min; 2x/day; 5d/wk; 4 or 8wks; 50% MIP; adjusted weekly to maintain MIP | NEADL; 6MWT; MIP; 8wks was better for those with weaker MIP at baseline |

| Inzelberg et al (2005) | Adults with Parkinson’s disease (Hoehn and Yahr stage II and III) | Outpatient | 30 min; 6d/wk; 12wks; 15% MIP; increased by 5-10% to 60% MIP at 4wk; adjusted monthly to maintain MIP | Perception of dyspnea; Inspiratory muscle endurance; MIP |

| Soumyashree and Kaur (2020) | Adults with paraplegia (T1-T12; >3 months) | IRF | 15 min; 5d/wk; 4wks; 40% MIP; progressed completing 50 breaths without difficulty for 3 days | 12MWAT; 6MPT; Dyspnea (modified BORG); MIP; MEP |

| Bargi et al (2016) | Oncology patients s/p allogeneic HSTC (>100 days post-transplant) | Outpatient | 30 min; daily; 6wks; 40% MIP | 6MWT; MSWT; Dyspnea (modified BORG); Depression; MIP; MEP |

| Dahhak, Devoogdt, and Langer (2022)* | Stable patients with breast cancer | Outpatient | 30 breaths; 2x/day; daily; 12 wks; 50% MIP | Endurance on cycling test; Dyspnea (modified BORG); Respiratory muscle endurance; MIP |

* training device used was an electronic flow resistive training device

Training Inspiratory Muscles

The primary objective of IMT is to provide load or resistance to the muscles of inspiration. This section will review the types of IMT devices, considerations for selecting an appropriate device to load the inspiratory muscles as well as dosing recommendations to help improve strength of the inspiratory muscles. As previously discussed, IMT effectively enhances respiratory muscle strength, and decreases the workload of breathing at rest which translates into a reduction of symptoms and improved function and movement.

Types of Inspiratory Muscle Training Devices

There are two categories of manual, handheld devices used to strengthen inspiratory muscles. The first involves loading inspiratory muscles based on flow resistance. This type of resistance is attained by incrementally narrowing the aperture through which air flows during inspiration, synonymous to sipping through a straw where more effort is required when the diameter of the straw is reduced. Flow resistance inspiratory muscle training devices offer varying levels of resistance to strengthen the inspiratory muscles. Unfortunately, the amount of load provided cannot be objectively measured as it depends on both the size of the opening and the flow rate of air through the device. When considering the example previously mentioned, sipping very slowly through a straw of narrow diameter triggers relatively less effort than sipping more rapidly through a straw of equivalent diameter.

Clinicians may be familiar with one specific airflow resistance device on the market named “The Breather” manufactured by PN Medical. The device can be adjusted to provide inspiratory and expiratory resistance during continuous breathing in a model described by the manufacturer as complete respiratory muscle training. The device has six levels of resistance, however the objective amount of resistance at each level is not standardized and varies based on flow rate that is directly impacted by the patient’s inspiratory and expiratory effort. As an example, resistance at a particular setting on the Breather ranges from 10-52 cm H2O at a low flow rate of 30L/min, with a much larger resistance range of 35-243 cm H2O provided at a higher flow rate of 60L/min at the same respective resistance settings.

The second category of inspiratory training devices that are widely used and extensively investigated are threshold pressure loading devices. With this device the patient breathes in through a mouthpiece and a loaded valve opens to allow airflow only when inspiratory force is adequate to overcome the set resistance. Threshold pressure loading devices offer specific and adjustable resistance that can be increased incrementally at every setting. Unlike the first category of inspiratory muscle training devices that load muscles based on flow, threshold pressure devices do not rely on the individual’s effort during inspiration and thereby allow the clinician to precisely measure the amount of resistance at each setting.

When comparing the two categories of devices, it is important to note that the threshold pressure devices are proliferating in the market as they do not rely on a patient’s inspiratory effort and are able to provide objective levels of resistance. A study by Dietsch et al. compared devices with expiratory resistance and reported that the minimum trigger pressure to generate a breath through The Breather was less than 6 cm H2O, even at the highest resistance setting. This finding highlights the significant difference in function between The Breather and threshold pressure devices. Most research investigating IMT typically uses a handheld threshold training device, where the patient inspires through a mouthpiece and a loaded valve opens to allow airflow only when inspiratory force is adequate to overcome the set resistance. Conversely, research on the Breather is relatively less and to our knowledge there is no investigation that compares outcomes of The Breather versus inspiratory training with threshold resistance. In light of the benefit of objectively quantifying the resistance offered with a pressure device along with the research supporting its efficacy, the subsequent narrative will focus on training inspiratory muscles using a handheld threshold pressure device.

Selection of an Inspiratory Muscle Training Device

The first consideration when choosing a certain handheld threshold pressure device involves choosing a device that is inclusive of the desired resistance range based on the client’s MIP. The device needs to offer adequate maximal resistance that can meet the client’s needs as inspiratory muscle strength improves. Studies investigating IMT have incorporated a broad range of training resistance, most commonly 30-80% MIP, with some specific protocols as low as 15% MIP and some as high as 90% MIP.

The second consideration is the adjustability of the handheld device, which encompasses both the number of discrete resistance settings and the increment of change when moving from one setting to the next. Devices with a high number of resistance settings and relatively small increment of change with each setting are desirable, as the client will have multiple options for setting the initial resistance and can feasibly move between settings to increase or decrease the resistance as desired. Consider, for example, a client whose baseline MIP is around 50 cm H2O. A device such as the PowerBreathe Classic (Light) has nine resistance settings but only four options in the appropriate resistance range: 10, 20, 30 or 40 cm H2O, representing 20%, 40%, 60% or 80% MIP respectively. Conversely, the Big Breathe V-PEP/EMT, a device that also has nine discrete settings, provides use of 7 of the 9 settings with resistance between 20 and 85% of MIP. In this device only the lowest setting and highest setting fall outside the appropriate resistance for this client, and it is likely that the highest setting of 46 cm H2O (92% of baseline MIP) could be used later as the client’s inspiratory strength improved with training. Another appropriate choice is the Aspire EMST 75 with inspiratory adaptor, which can be adjusted to a much greater range of values. Resistance on this device is set by first rotating the dial to bring the marker in line with the desired initial resistance. For our example patient with a MIP of 50 cm H2O, the starting point could be set at 15 cm H2O representing 30% of MIP. Once the marker has been set close to desired initial resistance, fine adjustments can be made to the training load where each quarter turn of the dial clockwise or counterclockwise yields an increase or decrease in resistance, in increments of 2.5-5 cm H2O (5-10% MIP for this example).

The final consideration when choosing a device involves an understanding of the pros and cons of each device based on the client’s unique priorities, including cost, insurance coverage, design, and various additional features. The Big Breathe V-PEP/IMT, for example, combines inspiratory training and vibratory positive expiratory pressure, a mechanism that aids in mobilizing secretions from the airways. This device would not provide adequate resistance for a client with a relatively higher MIP but could be invaluable for a client whose needs include inspiratory muscle training at a lower resistance as well as airway clearance techniques. Other devices, such as those manufactured by Aspire, can be used for both inspiratory and expiratory muscle training, which may be desirable for a client with expiratory muscle weakness and impairments in speech or swallowing. The PowerBreathe Plus IMT devices have an associated mobile application for patients to track their training and progress over time. This consideration can be vital in maximizing adherence as empirical evidence showcases that the benefits of IMT are diminished by limited adherence to the prescribed intervention. Device selection should be individualized with the goal of maximizing consistent use of the chosen device.

Dosing Recommendations

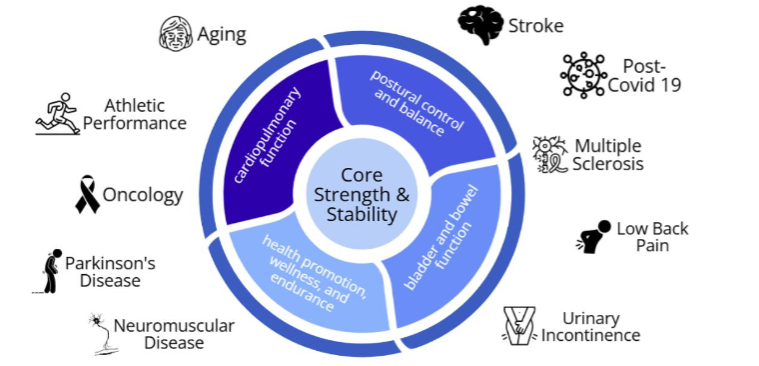

Published treatment protocols for IMT vary widely with respect to intensity, frequency, duration or repetitions, and overall length of the intervention. As IMT is a form of resistance training, it is prudent to follow similar principles as those used in resistance training of the peripheral muscles. In general, the total volume of work needs to be assessed when attempting to increase or decrease the dose of intervention. In order to quantify inspiratory training volume across varying IMT protocols, Palermo et al. defined the variable “Work-%” as the total number of weekly training breaths (repetitions x sets x sessions per week) multiplied by the resistance (expressed as %MIP). Our recommendations for dosing reflect adaptation of the American College of Sports Medicine guidelines for peripheral strength training. With guidelines for strengthening peripheral muscles in mind, complemented by a review of the literature that has investigated IMT, we propose using Work-% to create categories of low, moderate, or high inspiratory muscle training volume.

Our recommended initial dose for IMT prescription is the moderate training volume category. Clinicians and patients can work collaboratively to select the specific resistance, repetitions, sets, and treatment frequency alongside resistance dosed at a percentage of the MIP, that place the patient in a moderate level of IMT. As an example, all four of the following prescriptions result in a similar amount of weekly inspiratory work:

- 80% MIP x 5 repetitions x 5 sets x 2 sessions/week = 40 (equivalent full-capacity breaths per week)

- 50% MIP x 8 repetitions x 3 sets x 3 sessions/week = 45

- 30% MIP x 15 repetitions x 3 sets x 3 sessions/week = 40.5

- 30% MIP x 10 repetitions x 3 sets x 5 sessions/week = 45

These examples illustrate use of our guidelines to achieve moderate training volume in a variety of scenarios. A higher resistance, for example, can allow a client to reduce repetitions and treatment frequency. This approach is synonymous to short bouts of higher intensity aerobic exercise (running) achieving similar total aerobic exercise volume compared to longer bouts of moderate aerobic exercise (walking).

Figure 3 also provides considerations for titrating intensity to a higher or lower training volume. Lowering training volume may be necessary in scenarios where the load is inappropriately high. Conditions when training volume needs to be reduced include clients that have experienced a decline in overall health or an exacerbation of a chronic health condition, or when the clinician observes that the client is unable to tolerate the training as prescribed. Signs and symptoms of intolerance could include excessive use of the accessory muscles of breathing, moderate to severe dyspnea that does not resolve within a few minutes after stopping exercise, a rating of perceived exertion much higher than expected for a given exercise intensity, or symptoms of dizziness or lightheadedness. Training can be titrated to a lower volume by decreasing one or more of the variables included in Work-%, as appropriate for the patient. The ranges shown in figure 3 represent the lowest values for resistance, repetitions, sets and frequency that have been reported in various IMT protocols. It is important to note that each variable does not need to be reduced, but rather adjusted in a way that ensures the overall volume represented as Work-% is reduced.

Alternatively, there are indications to increase the volume of inspiratory training. A client who engages in IMT, tolerates the treatment well, and finds improvement may wish to increase the weekly training load with progressively greater resistance. For athletes seeking performance enhancement, Shei and colleagues suggest that the training principle of periodization, where purposeful variation of training load during defined time periods could be applied to IMT, just as periodization is used with other types of exercise interventions. High-volume IMT with moderate to high resistance and a frequency of up to twice daily has been shown to benefit individuals who are recovering after an abrupt change in inspiratory muscle strength due to a variety of medical conditions such as cardiothoracic surgery or acute respiratory failure. In each of these patient populations, utilizing a higher volume of training was shown to achieve more rapid gains in inspiratory muscle strength over a shorter time period.

Alternative Approaches

While the best evidence supports the use of an inspiratory muscle training device, not all clinicians may have access to these devices. For clinicians or patients who are unable to access an inspiratory muscle trainer, there may be value for achieving benefits of IMT with alternative methods of loading the respiratory muscles. The full scope of the options for inspiratory muscle training without a device is beyond the scope of this paper. Nevertheless, some examples include the use of weighted diaphragmatic breathing in supine or resisted chest expansion with a TheraBand in any position to add load on the muscles of respiration. Alternatively, a weighted vest can also add increased load to the respiratory muscles. It may be valuable to note that a weighted vest has the potential to not only load the inspiratory muscles but also increase cardiovascular intensity. In all these examples, it is important to be mindful that these alternative methods do not allow the clinician to objectively quantify the load provided to the inspiratory muscle.

Holistic Health Optimization

Physical therapists are challenged to move beyond disease-specific interventions for isolated conditions and consider utilizing interventions that are likely to improve holistic health and wellbeing in their patients and clients. Furthermore, physical therapists treat increasingly complex patients who present with impairments in multiple interconnected facets of the movement system. The American Geriatric Society defines multicomplexity as the intricate and interconnected health challenges often faced by older adults. Older adults are not only faced with their primary medical condition but also the combined and interactive effects of multiple other chronic diseases, functional limitations, and possible cognitive impairments. One such holistic intervention is IMT, which has shown to be beneficial in improving outcomes for a variety of patient populations. Figure 4 depicts the holistic impact of IMT. At the center, IMT contributes to core strength and stability. Strengthening inspiratory muscles not only assists with breathing but also plays key roles in postural control, maintaining trunk stability, improving speech, and bladder control. Figure 4 showcases the benefits of IMT across several populations, from athletes to older adults, individuals with post-covid syndrome, persons living with chronic conditions including heart failure, obstructive lung disease, neurodegenerative disorders, as well as improving outcomes in people with urinary incontinence and low back pain.

Safety Considerations

Inspiratory muscle training has been shown to be safe in a variety of patient populations and settings, including patients with critical illness. Nevertheless, it is prudent to consider situations that could be affected by the changes in force and pressure throughout the upper airways, thorax and abdomen during IMT. A review of the literature depicts a variety of precautions but no strict contraindications for using IMT in clinical practice. Following review of the literature, we recommend that clinicians carefully consider the appropriateness, expected benefits and potential risks of IMT for individuals with the following conditions: spontaneous pneumothorax; burst eardrum or other middle ear pathologies; large bullae in the lungs; severe osteoporosis with history of rib fractures; upper airway mass/stenosis; heart failure with significantly elevated left ventricular end diastolic pressure; hemodynamic instability; epistaxis; recent trauma to the mouth or face; unmanaged chronic cardiopulmonary conditions; and recent surgery to the abdomen, lungs, esophagus, head or neck. Further, it may be prudent to recommend clients who are experiencing an acute cold, sinusitis or respiratory tract infection pause their inspiratory training program until the condition has resolved. Additionally, it is imperative to routinely assess each client’s response to inspiratory training and modify or terminate the intervention when necessary. Clinicians must be particularly alert for worsening signs and symptoms of heart failure, oxygen desaturation, and declining performance of the inspiratory muscles, both during and after training. In order to maximize safety and efficacy, individuals should first perform IMT under the supervision of a skilled clinician and should not perform unsupervised IMT until they have received education on expected and unexpected responses to the intervention. Lastly, patients need to be educated on reviewing manufacturer recommendations for cleaning and sanitizing the devices to reduce the possibility of infections.

Conclusion

This perspective paper guides physical therapists on explicit ways to apply and integrate the evidence on IMT into daily patient care. Through discussion of the underpinnings of each aspect of the BREATHS framework and its application to practice, clinicians can appreciate the power of IMT in maximizing overall health and wellness. Our hope is that this novel BREATHS paradigm will challenge clinicians to think beyond routine treatment and be inspired to incorporate inspiratory muscle training in the holistic management of patients across the continuum of care.

References:

- American Physical Therapy Assoc. Vision Statement for the Physical Therapy Profession | APTA. Accessed April 27, 2025. https://www.apta.org/apta-and-you/leadership-and-governance/policies/vision-statement-for-the-physical-therapy-profession

- American Physical Therapy Association. Physical Therapist Practice and the Movement System | APTA.; 2015. Accessed May 8, 2025. https://www.apta.org/patient-care/interventions/movement-system-management/movement-system-white-paper#

- Poddighe D, Van Hollebeke M, Rodrigues A, et al. Respiratory muscle dysfunction in acute and chronic respiratory failure: how to diagnose and how to treat? European Respiratory Review. 2024;33(174):240150. doi:10.1183/16000617.0150-2024

- Smith JR, Taylor BJ. Inspiratory muscle weakness in cardiovascular diseases: Implications for cardiac rehabilitation. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2022;70:49-57. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2021.10.002

- Huang MH, Fry D, Doyle L, et al. Effects of inspiratory muscle training in advanced multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;37. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2019.101492

- Inzelberg R, Peleg N, Nisipeanu P, Magadle R, Carasso RL, Weiner P. Inspiratory muscle training and the perception of dyspnea in Parkinson’s disease. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 2005;32(2):213-217. doi:10.1017/S0317167100003991

- Martin-Sanchez C, Barbero-Iglesias FJ, Amor-Esteban V, Martin-Sanchez M, Martin-Nogueras AM. Benefits of inspiratory muscle training therapy in institutionalized adult people with cerebral palsy: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Brain Behav. 2024;14(9). doi:10.1002/BRB3.70044

- Beaumont M, Forget P, Couturaud F, Reychler G. Effects of inspiratory muscle training in COPD patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Respiratory Journal. 2018;12(7):2178-2188. doi:10.1111/CRJ.12905

- Azambuja ADCM, De Oliveira LZ, Sbruzzi G. Inspiratory Muscle Training in Patients with Heart Failure: What Is New? Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Phys Ther. 2020;100(12):2099-2109. doi:10.1093/PTJ/PZAA171

- Zhang X, Zheng Y, Dang Y, et al. Can inspiratory muscle training benefit patients after stroke? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Rehabil. 2020;34(7):866-876. doi:10.1177/0269215520926227

- Watson K, Egerton T, Sheers N, et al. Respiratory muscle training in neuromuscular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Respiratory Review. 2022;31(166). doi:10.1183/16000617.0065-2022

- Fabero-Garrido R, del Corral T, Angulo-Díaz-Parreño S, et al. Respiratory muscle training improves exercise tolerance and respiratory muscle function/structure post-stroke at short term: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2022;65(5). doi:10.1016/j.rehab.2021.101596

- Laveneziana P, Albuquerque A, Aliverti A, et al. ERS statement on respiratory muscle testing at rest and during exercise. European Respiratory Journal. 2019;53(6). doi:10.1183/13993003.01214-2018

- Adler D, Janssens JP. The pathophysiology of respiratory failure: Control of breathing, respiratory load, and muscle capacity. Respiration. 2019;97(2):93-104. doi:10.1159/000494063

- Severin R, Franz CK, Farr E, et al. The effects of COVID-19 on respiratory muscle performance: making the case for respiratory muscle testing and training. European Respiratory Review. 2022;31(166). doi:10.1183/16000617.0006-2022

- Huber JE, Chandrasekaran B, Wolstencroft JJ. Changes to Respiratory Mechanisms during Speech as a Result of Different Cues to Increase Loudness. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2005;98(6):2177. doi:10.1152/JAPPLPHYSIOL.01239.2004

- Janssens L, Brumagne S, Polspoel K, Troosters T, McConnell A. The effect of inspiratory muscles fatigue on postural control in people with and without recurrent low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35(10):1088-1094. doi:10.1097/BRS.0B013E3181BEE5C3

- Costa R, Almeida N, Ribeiro F. Body position influences the maximum inspiratory and expiratory mouth pressures of young healthy subjects. Physiotherapy. 2015;101(2):239-241. doi:10.1016/J.PHYSIO.2014.08.002

- Lista-Paz A, Langer D, Barral-Fernández M, et al. Maximal Respiratory Pressure Reference Equations in Healthy Adults and Cut-off Points for Defining Respiratory Muscle Weakness. Arch Bronconeumol. 2023;59(12):813-820. doi:10.1016/j.arbres.2023.08.016

- Vargus-Adams JN, Majnemer A. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) as a framework for change: Revolutionizing rehabilitation. J Child Neurol. 2014;29(8):1030-1035. doi:10.1177/0883073814533595

- Ahmadnezhad L, Yalfani A, Borujeni BG. Inspiratory muscle training in rehabilitation of low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. J Sport Rehabil. 2020;29(8):1151-1158. doi:10.1123/JSR.2019-0231

- Charususin N, Gosselink R, Decramer M, et al. Randomised controlled trial of adjunctive inspiratory muscle training for patients with COPD. Thorax. 2018;73(10):942-950. doi:10.1136/THORAXJNL-2017-211417

- Craighead DH, Heinbockel TC, Freeberg KA, et al. Time-efficient inspiratory muscle strength training lowers blood pressure and improves endothelial function, no bioavailability, and oxidative stress in midlife/older adults with above-normal blood pressure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(13). doi:10.1161/JAHA.121.020980

- Abidi S, Ghram A, Ahmaidi S, Ben Saad H, Chlif M. Effects of Inspiratory Muscle Training on Stress Urinary Incontinence in North African Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int Urogynecol J. 2024;35(10). doi:10.1007/S00192-024-05921-1

- Chang YC, Chang HY, Ho CC, et al. Effects of 4-week inspiratory muscle training on sport performance in college 800-meter track runners. Medicina (Lithuania). 2021;57(1):1-8. doi:10.3390/MEDICINA57010072

- Bosnak-Guclu M, Arikan H, Savci S, et al. Effects of inspiratory muscle training in patients with heart failure. Respir Med. 2011;105(11):1671-1681. doi:10.1016/J.RMED.2011.05.001

- Doğan YE, Yıldırım MA, Öneş K, Kütük B, Ata İ, Karacan İ. The optimal treatment duration for inspiratory muscle strengthening exercises in stroke patients: a double-blinded randomized controlled trial. Top Stroke Rehabil. Published online 2024. doi:10.1080/10749357.2024.2423591

- Soumyashree S, Kaur J. Effect of inspiratory muscle training (IMT) on aerobic capacity, respiratory muscle strength and rate of perceived exertion in paraplegics. Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine. 2020;43(1):53-59. doi:10.1080/10790268.2018.1462618

- Dahhak A, Devoogdt N, Langer D. Adjunctive Inspiratory Muscle Training During a Rehabilitation Program in Patients with Breast Cancer: An Exploratory Double-Blind, Randomized, Controlled Pilot Study. Arch Rehabil Res Clin Transl. 2022;4(2). doi:10.1016/j.arrct.2022.100196

- Barğı G, Güçlü MB, Arıbaş Z, Akı ŞZ, Sucak GT. Inspiratory muscle training in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients: a randomized controlled trial. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2016;24(2):647-659. doi:10.1007/S00520-015-2825-3

- Palau P, Domínguez E, Gonzalez C, et al. Effect of a home-based inspiratory muscle training programme on functional capacity in postdischarged patients with long COVID: The InsCOVID trial. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2022;9(1). doi:10.1136/BMJRESP-2022-001439

- Abodonya AM, Abdelbasset WK, Awad EA, Elalfy IE, Salem HA, Elsayed SH. Inspiratory muscle training for recovered COVID-19 patients after weaning from mechanical ventilation: A pilot control clinical study. Medicine. 2021;100(13):e25339. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000025339

- Palau P, Domínguez E, López L, et al. Inspiratory Muscle Training and Functional Electrical Stimulation for Treatment of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: The TRAINING-HF Trial. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2019;72(4):288-297. doi:10.1016/j.rec.2018.09.004

- Shoemaker MJ, Dias KJ, Lefebvre KM, Heick JD, Collins SM. Physical Therapist Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Individuals with Heart Failure. Phys Ther. Published online 2020. doi:10.1093/ptj/pzz127

- Dietsch AM, Krishnamurthy R, Young K, Barlow SM. Instrumental assessment of aero-resistive expiratory muscle strength rehabilitation devices. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2024;67(3):729-739. doi:10.1044/2023_JSLHR-23-00381

- Lee CT, Chien JY, Hsu MJ, Wu HD, Wang LY. Inspiratory muscle activation during inspiratory muscle training in patients with COPD. Respir Med. 2021;190. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2021.106676

- Kim SH, Shin MJ, Lee JM, Huh S, Shin YB. Effects of a new respiratory muscle training device in community-dwelling elderly men: an open-label, randomized, non-inferiority trial. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1). doi:10.1186/S12877-022-02828-8

- Sørensen D, Christensen ME. Behavioural modes of adherence to inspiratory muscle training in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a grounded theory study. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(9):1071-1078. doi:10.1080/09638288.2017.1422032

- Palermo AE, Butler JE, Boswell-Ruys CL. Comparison of two inspiratory muscle training protocols in people with spinal cord injury: a secondary analysis. Spinal Cord Ser Cases. 2023;9(1). doi:10.1038/S41394-023-00594-2

- Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, et al. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: Guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(7):1334-1359. doi:10.1249/MSS.0B013E318213FEFB

- Shei RJ, Paris HL, Sogard AS, Mickleborough TD. Time to Move Beyond a “One-Size Fits All” Approach to Inspiratory Muscle Training. Front Physiol. 2022;12. doi:10.3389/FPHYS.2021.766346

- Dsouza FV, Amaravadi SK, Samuel SR, Raghavan H, Ravishankar N. Effectiveness of Inspiratory Muscle Training on Respiratory Muscle Strength in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgeries: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis. Ann Rehabil Med. 2021;45(4):264-273. doi:10.5535/ARM.21027

- Bissett BM, Wang J, Neeman T, Leditschke IA, Boots R, Paratz J. Which ICU patients benefit most from inspiratory muscle training? Retrospective analysis of a randomized trial. Physiother Theory Pract. 2020;36(12):1316-1321. doi:10.1080/09593985.2019.1571144

- Tinetti M, Huang A, Molnar F. The Geriatrics 5M’s: A New Way of Communicating What We Do. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(9):2115-2115. doi:10.1111/JGS.14979

- Rozek-Piechura K, Kurzaj M, Okrzymowska P, Kucharski W, Stodółka J, Maćkała K. Influence of Inspiratory Muscle Training of Various Intensities on the Physical Performance of Long-Distance Runners. J Hum Kinet. 2020;75(1):127-137. doi:10.2478/HUKIN-2020-0031

- Fernández-Lázaro D, Gallego-Gallego D, Corchete LA, et al. Inspiratory muscle training program using the powerbreath®: Does it have ergogenic potential for respiratory and/or athletic performance? a systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(13). doi:10.3390/IJERPH18136703

- Nickels M, Erwin K, McMurray G, et al. Feasibility, safety, and patient acceptability of electronic inspiratory muscle training in patients who require prolonged mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit: A dual-centre observational study. Australian Critical Care. 2024;37(3):448-454. doi:10.1016/j.aucc.2023.04.008

- Luo Z, Qian H, Zhang X, Wang Y, Wang J, Yu P. Effectiveness and safety of inspiratory muscle training in patients with pulmonary hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9. doi:10.3389/FCVM.2022.999422

- McDonald T, Stiller K. Inspiratory muscle training is feasible and safe for patients with acute spinal cord injury. Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine. 2019;42(2):220-227. doi:10.1080/10790268.2018.1432307

- Cahalin LP, Arena R, Guazzi M, et al. Inspiratory muscle training in heart disease and heart failure: A review of the literature with a focus on method of training and outcomes. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2013;11(2):161-177. doi:10.1586/ERC.12.191

- Alpert MA. Beneficial Effects of Inspiratory Muscle Training in Patients With Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. American Journal of Cardiology. 2023;203:526-527. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2023.07.129