Organ Donation: Analyzing Presumed Consent Legalities

Does silence imply consent? Organ Donation and the Presumption of Informed Consent

Ronald Cárdenas Krenz1; Edwin Cordova Pérez2

- Law PHD from the Public University of Navarra and the University of Salamanca. Master in Bioethics and Biolegal. Master in Civil and Commercial Law. Dean of the Faculty of Law of the University of Lima. Co-founder of the UNESCO Chair of Bioethics and Biojuridics at the Women’s University of the Sacred Heart. Member of the Pontifical Academy for Life. Member of the Academy of Law and Social Sciences of Córdoba. Former National Superintendent of Public Registries of Peru.

- Lawyer from the University of Lima. Master in Governance & Human Rights from the Autonomous University of Madrid. Teaching assistant of the Civil Law I Course (General Principles and Natural Persons) of the Faculty of Law of the University of Lima.

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 December 2024

CITATION: KRENZ, Ronald Cárdenas; PÉREZ, Edwin Cordova. Does silence imply consent? Organ Donation and the Presumption of Informed Consent. Medical Research Archives, [S.l.], v. 12, n. 12, dec. 2024. Available at: <https://esmed.org/MRA/mra/article/view/6003>.

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v12i12.6003

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

In response to the global shortage of organ donation, each country has been applying different public policies to reduce the donor deficit. One of them has been to propose regulatory modifications to the presumed consent system, in order to establish a system in which a favorable will is presumed for post-mortem organ donation, unless the person has declared otherwise while alive.

Recently, the Peruvian law has established the presumed consent system for the donation of organs; it means that, in the absence of express will, the donor’s willingness to donate his or her organs at the time of death is now presumed. This regulatory modification follows a tendency established in other countries; however, others remain and respect the free and inform consent regards the willing of donating organs.

This article presents a critical vision of this legal presumption. Under analyzing others health legal systems, we deveal the risks of violation of people’s rights when applying a regulation in this sense, which establishes a kind of compelled solidarity, highlighting policies that promote organ donation without compromising fundamental rights.

Keywords

- Organ Donation

- Presumed Consent

- Informed Consent

- Legal Systems

- Human Rights

Introduction

The donation of certain organs, whether inter vivos or mortis causa, by a person to share them with their peers altruistically and within the legally defined margins, responds – as La Cruz said- to a valuable social interest, given its humanitarian inspiration, taking into account the voluntariness of the transfer and the principles that govern it (legality, altruism and clear benefit in favor of the recipient).

According to Kant, self-disposal is impermissible because we have no property rights over ourselves; we have ownership over things, not over people; furthermore, it would be incoherent for someone to be both owner and property of himself.

Thus, we can say that when referring to the disposition of an organ, we are not speaking about the disposition of a possession that belongs to us, as we might when exercising property rights, but rather about the disposition of a part of our very being. As Espinoza states, a person is empowered to dispose of themselves (within the category of being) and not of an entity separate from themselves (the body mistakenly understood as an object of rights, within the category of having). The prohibition made by legal systems on the sale of organs is inspired by the solidarity and humanitarian nature that such transfer must have, and must be absolutely unrelated to any lucrative purpose.

One of the most important problems in health is the lack of requirement for organs for transplantation. Many patients die around the world because they do not have a donor who can give them the organ they need. In fact, according to statistics from the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), 17 people die every day waiting for an organ transplant, which reflects a reality that hides behind prejudices, cultural issues, the fear of generating a market for organs or poorly understood religious ideas.

In order to obtain more organs, various alternatives have been proposed, such as the possibility of selling organs, using animal organs (xenotransplants) or the creation of artificial organs. The first measure is questionable for moral, legal and principled reasons, its discriminatory drift (it would be the poor who would end up donating their organs to the wealthiest), its reifying or commercializing nature of the human being, the impact on integrity and dignity of the person, and others consequences. As for the second, it seems interesting, but there are still serious doubts regarding its viability and side effects. And, regarding the third, being perhaps the most promising, in reality little progress has yet been made.

However, there is another alternative already applied today in various countries, which does not require further studies or economic investment for its implementation, and is simply applicable through a regulatory modification: the establishment of the presumed consent system, that is, the presumption that all people are willing to donate their organs, unless they have expressly declared otherwise.

In fact, countries such as Chile, Colombia, France and Switzerland have been applying this system. Brazil also had it at the time, but then backed down. This system is the opposite of the system of presumption of negative will, by which it is assumed that a person does not wish to donate their organs, unless they have expressly declared otherwise. This is what Germany, Mexico, the US and Italy have established.

Peru is one of the countries that has most recently opted for the presumed consent system. Thus, on May 30, 2023, it was published in the legal gazette official of the Peruvian state, Law No. 31756, through which this system for organ donation is established, through the following text:

“Article 3. Universal presumption of donation Authorization for the extraction and processing of organs or tissues from cadaveric donors is presumed, unless otherwise declared by the owner or exception established in this law. Every citizen can freely record in their national identity document (NID) the declaration of their will not to be an organ or tissue donor, in accordance with the provisions of article 32, literal k), of Law 26497, Organic Law. of the National Registry of Identification and Civil Status (Reniec), whose content guarantees the right to informed consent of the holders for the donation of organs or tissues. Likewise, you will have the simplified means to declare your desire not to be a donor that its available by the Ministry of Health, in accordance with the procedures established by the regulations of this law.”

The purpose of the rule, in essence, is that, if a person did not say in life that they wanted to donate their organs upon death, it is understood that they do wish to do so, without the possibility of their relatives opposing their decision.

It is worth noting that there are numerous cases in which the person declares while alive that he wanted to donate his organs upon death to save other lives, but this is not carried out due to opposition from family members, which – while still being important – is a problem different from the object of this work, which is why we will not have to develop it, although in any case we will see in due course how it can appear on the scene.

Spain is the country that has led the world in the number of organ donors for 32 years, with a deceased donor rate of 48.9 per million inhabitants, which represents more than double the European Union average, having been 2023 a record year with 5,861 transplants.

But Spain is the exception, not the rule. And so, around the world many patients wait anxiously for an organ that will restore their health and save their lives, waiting for a generous act of solidarity, which many times never arrives.

We can ask ourselves then: If life is priceless, at what cost should we save it? Could it be that sometimes the end does justify the means? Should the presumed consent system be promoted in order to have more bodies available taking into account its immediate applicability, practicality and legal viability, leaving aside other solutions that address the problem in a more structural way?

The matter may seem like a purely legal issue, but it is not. The doctors are the ones who must face the desperation and pain of patients who do not get the organs that their health requires. It’s them, not the legislators. And the doctors, as health professionals, also share the frustration from the patients that do not have organs available to save their lives and carry out their work.

On the other hand, in a system where the possibility of extracting organs without permission from relatives is established, who are the ones who would face the claim and accusations from them when they find out that the organs of their deceased relatives were extracted? These are also the doctors who would have to bear this and all the complaints that are generated, no matter how unfounded they may be, having to face legal processes, attacks on social networks and many other things, running the risk that when justice finally finds them right, their prestige will have been seriously dented and they will have had to allocate a whole series of resources to defend themselves not only legally, but also socially and professionally.

Methodology

To prepare this article, we have started from the recently legal changes regards donation organs in Peru in 2023, so that we elaborate this paper under a bibliographic methodology based in legal sources of different countries, analyzing the impacts of free and inform consent in several health legislation of principal’s donation organs systems in the world.

The fundamental objective of the research is to analyze whether the presumed consent system in terms of organ donation is, in general, the most ethically appropriate to address the medical and social problem of the shortage of organs for transplant, which affects many patients in different parts of the world.

Donation organs Models

The issue of organ disposal is inevitably delicate, sensitive and complex. As Aramini points out: “Even for moralists the positions are quite differentiated: for some, explicit consent to donation is essential; for others, society can dispose of, based on the principle of solidarity, the organs of those deceased people who have not expressed their willingness to donate while they were alive.”

The moral discussion, by the way, has permeated legal regulation. Before entering into it, it is necessary to make some preliminary considerations.

Organ transplant can be defined as “the replacement of a part of the human body with another extracted from another body or animal, and that fulfills the same functions as the replaced one.” For Porter et al, organ transplantation can be briefly defined as “the surgical replacement of tissues and organs,” having also been defined as “the transfer of cellular material or tissue, living or dead, from one part to another of the same living organism, or from one individual to another.” It is important to remember that, modernly, there are also some transplants that can be done using artificial organs, with plastic heart valves, pacemakers, ear implants, etc. having existed for some time.

Now, since an organ or tissue is not a patrimonial asset, it should be noted that, in the strict sense, one should not speak of “donation” of organs, since legally the concept refers to a contract that, as such, has patrimonial content (as indicated in article 1351 of the Peruvian Civil Code); hence the most appropriate term is “assignment” as Espinoza points out. However, since the term “organ donation” has permeated society and is widely accepted, we will use it throughout the work, leaving a record of what was noted.

a) Countries in favor of the presumed consent system

Among the legal systems that apply the legal universal presumption of donation, unless expressly stated otherwise, we have:

Argentina: Law No. 27447, Law on Transplantation of Organs, Tissues and Cells, after pointing out some requirements for organ donation, states that:

“Article 31.- (…) If the affirmative will to donate is not restricted or its purpose is not conditioned, all organs and tissues, and both purposes, are understood to be included.”

Chile: According to Law No. 20,673, which modifies Law No. 19,451 regarding the determination of who can be considered organ donors, it is established that:

“Article 2.- (…) Every person over eighteen years of age will be considered, by the sole operation of the law, as a donor of their organs once they have died, unless, until before the moment in which the extraction of the organ is decided, reliable documentation is presented, granted before public notary, in which it is stated that the donor during his lifetime expressed his will not to be one.”

As can be seen, the norm requires a notarial act for the declaration that a person wants to make of their refusal to be an organ donor.

Colombia: Law No. 1805 modified the provisions regarding the donation of anatomical components, leaving the legal presumption of donation as follows:

“Art. 2° It is presumed that one is a donor when a person during his or her life has refrained from exercising his or her right to oppose the removal of organs, tissues or anatomical components from his or her body after his or her death.”

Commenting on the topic, Carreño says that the fact of not expressing opposition to organ donation means, consequently, the legitimization of the donation of his organs by the interested party, “the presumption thus has a negative charge when not saying, that is, It is to affirm, to consent in perspective of a greater good. To oppose the donation, the person must expressly state that they do not wish to be a donor.”

It should be added that the same law adds that the revocation of being a donor can only be carried out by the interested party himself and cannot be replaced by his relatives or relatives.

Mexico: The criteria has recently been changed towards a presumed consent system, legislatively modifying articles 320° and 321° of the General Health Law, remaining in the following terms:

“Article 321.- Donation of organs, tissues, cells and corpses consists of the tacit or express consent of the person so that, during life or after death, their body or any of its components are used for transplants.”

(highlighting is ours) This recent regulatory modification legislating tacit consent reflects the legislator’s will to regulate a presumed consent system for organ donation.

b) Countries that assume the presumption of negative will

There is various comparative legislation in which, when a person dies without clearly stating his or her consent, his or her family members are called upon to do so.

Spain: It is relevant to highlight that; On the one hand, it does not expressly regulate the so-called “universal presumption of donation.” On the other hand, and according to Royal Decree 2070/1999, authorized health centers are required to corroborate, among other requirements, the following:

“Article 10. 1. Obtaining organs from deceased donors for therapeutic purposes may be carried out if the following conditions and requirements are met: (…): b) Whenever it is intended to proceed with the extraction of organs from deceased donors in an authorized center, the person who is responsible for giving consent for the extraction or who is delegated, as specified in article 11.3, must carry out the following relevant checks: 1. Information on whether the interested party made his or her wishes clear to any of his or her family members or the professionals who treated him or her at the health center, through the notes that they may have made in the Registration Book of Declarations of Will or in the medical history.”

This corroboration is not met if the donor expressed his will during his lifetime in an advance directive document; However, and according to Spanish medical sources, very few people do it.

It can be said that in Spain a soft voluntary exclusion system is applied, in the sense that everyone is presumed to be a donor by default, unless the family objects.

United States: Its legislation has been reinforcing the concept of the need for the donor’s will, so much so that in 2006 the Uniform Determination of Death Act was enacted. This Law prevents other people (whether family members or relatives) from revoking the consent given by the donor while alive. The focus is then on express consent to donate organs.

c) Others Europeans models

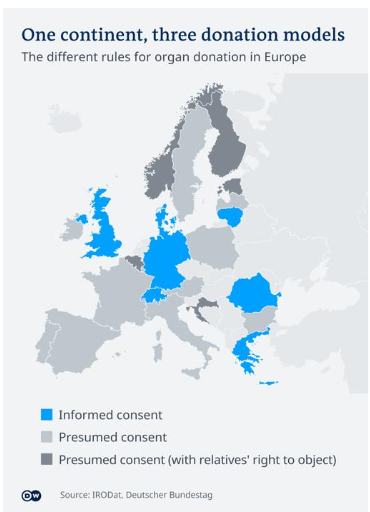

Beyond the Spanish case previously explained, there was a debate in Germany in 2019 about the new regulation of organ donation; By comparing the different regulatory models existing in European countries, we can determine the following:

- Informed consent: It is a kind of presumption of negative will under the premise that it is the State that must provide all possible information to the potential donor, so that there is no doubt about their will to donate when expressly expressed.

- Voluntary exclusion by the donor: This is what we would call a presumption of negative will per se, in which the person’s decision not to donate their organs will be always respected, without the State questioning their will to make the decision, even more so in contexts where there is a donor deficit.

- Voluntary exclusion due to objection from family members: This model has the particularity that it is the family members and/or relatives who can revoke the will regarding the organ donation of the deceased donor, in which the decision-making power of the donor can even be questioned. the family about the real will of the donor, beyond cases where there is duly declared inability to exercise or conscientious objections, as noted in a study by Perez Miras.

The following map shows the different regulation systems that we have previously explained:

Utilitarianism and organ donation: When the means does not justify the ends

Given the demand for organs, certain libertarian ideologies actively advocate for their sale. In fact, in his campaign for the presidential elections in Argentina, Javier Milei proposed this at some point.

From a strictly pragmatic perspective, this argument appears logical since it would allow obtaining a greater number of organs, it would avoid their informal trade, it would reduce the current costs (although illegal) to obtain them, etc.

However, it must be kept in mind that the human body is a res extracommercium, not susceptible to economic traffic; promoting the sale of organs would be an attack on human dignity, by objectifying the person, turning them from a subject into an object. However, “the transfer of blood, breast milk, hair, semen and other regenerable tissues is possible, but not their sale, since this distorts the value of solidarity in the community,” as Espinoza observes. As noted by Abellán and López, the body “makes” and “is” the person, it is the matter in which the person’s self is incarnated, singling out the personal being; thus, we do not “have” a body, but rather we are corporeal.

On the other hand, this alternative could generate new forms of discrimination, since there is no doubt that those who would enter the market to sell their organs would be the poorest, thus generating a new category of human beings: the complete and the incomplete.

To this would be added the possibility of abuse and intimidation so that a person sells their organs, without failing to mention the social problem in our countries where, in context of poverty, where many women do not work because they are taking care of their children, there would be a risk that they, in the absence or economic indifference of their partners, would be the ones who end up selling their blood today, a kidney tomorrow, and then who knows what.

It should be added that the fact that someone can buy an organ is so abhorrent that no country allows it, except Iran.

Additionally, it has been observed that by allowing the sale of organs, many people who today generously agree to do so would desist from doing so.

Thus, then, given the need for organs, the presumed consent system would seem to be a good alternative. Nevertheless, there are some issues that must be weighed:

- Could silence, in these cases, really be equated with assent?

- Would we really be talking about an altruistic act or would we be facing compelled solidarity imposed by the State?

- Is this a rule that facilitates the citizen’s desire to donate his organs, or would it rather mean taking advantage of the laziness, lack of economic resources or ignorance of the citizen who did not go to the respective State institution to express his refusal?

- Given an evident information asymmetry between the State and the administered regarding the issue, can we speak of tacit informed consent, or should this always be express, especially when dealing with such important issues, in which even (as we saw in some European countries) does the relatives’ objection weigh against revoking the donor’s will?

Positive will as presumption

Sunstein and Thaler say, “So far, implied consent seems like an excellent solution, but we have to point out that it cannot be considered a panacea either.”

In the countries of the region, with little knowledge of the laws by the majority of citizens, it could be argued that we are really dealing with tacit consent if the person did not express their refusal to donate their organs. These could simply be cases of ignorance of the law, in which the presumption of “positive will” would be the presumption of a non-existent will. In one case or another, the presumption of knowledge of the law could not be applied either, since- as we mentioned – little knowledge of the rules can prevent due analysis and reflection of the presumed consent system on the part of citizens, thus, there is a risk of potential violations of fundamental rights by violating the principle of informed consent, as contemplated by the World Medical Association when it requires States that any of the presumption models they adopt “must do everything possible to ensure that these policies have been adequately disclosed and do not affect the informed decision of the donor, including the patient’s right to refuse to donate.

On the other hand, the limitations in many countries for the State to have sufficient presence – making access to public records difficult – and the complexity of the geography in various latitudes, such as in Peru, could determine that many people, wanting to express their negative, they cannot do so, lacking a registry office nearby.

Additionally, having high poverty rates, there could also be the risk that a person, wanting to express their negative will and having a registry office at hand, will not do so due to lack of resources.

On the other hand, as Moreu Carbonell says: “in certain contexts “automatic accession” policies are counterproductive, especially when moral issues are involved, as occurs in organ donations.”

As we have said in another work, we reiterate that, in a presumed consent system, “there could be situations of taking advantage of the citizen’s apathy, his ignorance of the law or his lack of resources to process the manifestation of his “negative will, which can be particularly serious in countries where citizens have less access to state services.”

Final Reflexion

It is undoubtedly necessary to facilitate access to organs for patients who need it, fundamentally promoting voluntary donation, but also being able to resort to certain incentives such as nudges, a concept explained by Suntein and Thaler.

However, regarding the presumed consent system, we believe it can only be acceptable if there is sufficient assurance that the citizens of a country are aware that the State may use their organs upon their death, unless they have explicitly expressed otherwise during their lifetime. Otherwise, we would be taking advantage of their lack of knowledge, misinformation or ignorance. From a bioethical point of view, we would be going against the principle of informed consent; As the UNESCO International Bioethics Committee points out, “Consent must be express,” that is, it must leave no room for doubt as to what the will of the person involved is.

Donating organs may constitute a moral duty and a social duty, but not a legal one, since if we consider it this way we could run the risk of a nationalization of the organs that violates the altruistic and supportive nature that the transfer of organs should inspire.

The path of conviction and education is always longer, but it is the one we must follow to develop a culture of organ donation that is sustainable over time.

It would be preferable to require individuals to make an explicit decision on the matter, which they can do when requesting the issuance of their national identity document or driver’s license; In this way, it will be possible to have clear consents, that is, explicit, so that on that basis the pertinent provisions can be made at the time of the person’s death.

All of this, of course, along with the promotion of solidarity, of thinking about others; In short, to be consistent with our human condition.

Conclusions

- In the legal systems of societies with limited knowledge of the legal system and difficulties in accessing public services, the presumed consent system implies the risk of violating the rights of the person by assuming their desire to donate their organs upon death, ignoring their real willingness to donate their organs or not.

- The presumed consent system in matters of organ transfer can discourage the promotion of organ donation by the State, affecting the right to informed consent, resulting in a kind of compelled solidarity based on misinformation and ignorance of the subject on the part of citizens.

- Other alternatives can be proposed that promote organ transplantation and donation, through awareness and commitment campaigns, based on freedom and responsibility, that are more sustainable over time, based on a true spirit of solidarity, and without affecting fundamental rights, Spain and Italy being interesting cases that can serve as models.

Declaration of Conflict of Interest:

None

Financing Statement:

None

Declaration of Recognition:

None

References

- La Cruz Berdejo, José Luis; Sancho Rebullida, Francisco de Asís; Luna Serrano Agustín; Delgado Echeverría, Jesús; Rivero Hernández, Francisco; and Rams Albesa, Joaquín. Elements of Civil Law I. General Part Second Volume. 4th. Edition. Madrid: Dykinson, 2004:72-73.

- Espinoza, Juan. Right of the People. Volume I. 6ª. Edition. Lima: Grijley Legal Editor, 2012: 327.

- Fernández Sessarego, Carlos. Right of the People. Explanation of reasons and comments on the First Book of the Peruvian Civil Code. 10th. Edition. Lima: Grijley, 2007:59.

- US Government Health Resources and Services Administration Organ Donation Statistics. HRSA organ donation.gov. Published and Updated in March 2024. Accessed on July 22, 2024. https://donaciondeorganos.gov/conocer/2n8u/estadisticas-sobre-la-donacion-de-organos.

- “The donation of human organs is inserted within the beliefs and imaginaries that every society shares, which have been built as a culture, as a social fabric, strongly rooted as it wants (sic) that have to do with transcendental human aspects such as death, life, the body, the afterlife” (Carreño, 2016: 85).

- “Organ donation is not opposed even by faith in the resurrection, which according to Christian doctrine does not mean the material continuation of our earthly body, but rather the profound transformation of the entire man in a new reality that surpasses our capacity to understanding” (Aramini, 2007: 287).

- International Registry in Organ Donation and Transplantation (IRODaT). International Registry in Organ Donation and Transplantation, Preliminary numbers 2022. Published March 2023. Accessed July 22, 2024. https://www.irodat.org/img/database/pdf/IRODAT%20March%202023%20Preliminary%20report.pdf

- Agencies, Spain breaks the record for transplants with 5,861 in 2023 and has been the world leader for 32 years in a row. El País Newspaper. Published on January 17, 2024. Accessed on August 4, 2024. https://elpais.com/sociedad/2024-01-17/espana-bate-el-record-de-trasplantes-con-5861-en-2023-y-encadena-32-anos-seguidos-como-lider-mundial.html

- Aramini, Michele. Introduction to Bioethics. Bogotá: San Pablo, 2007: 284.

- Rubio Correa, Marcial. The human being as a natural person. 2a. edition. Lima, Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, 1995: 58.

- Porter K, Villalobos Pérez J, et al. Introduction to Bioethics. 3rd. Edition. Mexico, Méndez Editores, 2009: 183.

- Aramini, Michele. Introduction to Bioethics. Bogotá: San Pablo, 2007: 270.

- Espinoza, Juan. Right of the People. Volume I. 6ª. Edition. Lima: Editora Jurídica Grijley, 2012: 333.

- Congress of the Argentine Nation. Law No. 27447, Law on Transplantation of Organs, Tissues and Cells. Published in the Official Gazette of the Republic of Argentina on July 26, 2018. Accessed on July 23, 2024. https://www.boletinoficial.gob.ar/detalleAviso/primera/188857/20180726?busqueda=1

- Undersecretary of Public Health – Ministry of Health. Law No. 20,673, modifies Law No. 19,451 Regarding the Determination of Who Can Be Considered Organ Donors. Published in the Official Gazette of Chile on June 7, 2013. Accessed on August 4, 2024. https://www.diariooficial.interior.gob.cl/media/2013/06/07/do-20130607.pdf

- Congress of Colombia. Law No. No. 1805, by which law 73 of 1988 and law 919 of 2004 are modified on the donation of anatomical components and other provisions are issued. Published in the Official Gazette of Colombia on August 24, 2016. Accessed on August 4, 2024. https://svrpubindc.imprenta.gov.co/diario/view/diarioficial/consultarDiarios.xhtml

- Carreño Dueñas, Dalia; Restrepo Restrepo, José and Becerra, Jairo. “Socio-legal aspects of organ donation and transplantation in Colombia.” In: Various authors. Bioethics and teaching. Bogotá: University of Santo Tomás – Ibáñez Publishing Group, 2016: 81.

- Chamber of Senators, Draft decree that modifies articles 320, 321, 322, 324, 325, 326 and 329 of the General Health Law, approved on April 3, 2018. Available in http://www.senado.gob.mx/sgsp/gaceta/63/3/2018-04-03-1/assets/documentos/Dict_Salud_Donacion_de_Organos.pdf. Accessed June 2, 2018.

- Ministry of the Presidency. ROYAL DECREE 2070/1999, of December 30, which regulates the activities of obtaining and clinical use of human organs and the territorial coordination in matters of donation and transplantation of organs and tissues. Published in the Official State Gazette of Spain. Published on January 4, 2000. Accessed on July 31, 2024. https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2000/01/04/pdfs/A00179-00190.pdf

- For more information, access the information from the National Transplant Organization of Spain: https://www.ont.es/informacion-al-ciudadano-3/donacion-de-organos-3-4/#

- https://www.organdonor.gov/about-us/legislation-policy/history

- Perez Look. Conflicts of Conscience Faced with Organ Transplants. Law and Health Magazine, 2015; 25 (2): 81-97. https://www.ajs.es/es/index-revista-derecho-y-salud/volumen-25-numero-2-2015/conflictos-conciencia-los-trasplantes

- Prange De Oliveira, A and Hallan, M.. German lawmakers reject ‘opt-out’ organ donor bill. DW. Published January 16, 2020. Accessed July 22, 2022. https://www.dw.com/en/german-parliament-explicit-consent-still-necessary-from-organ-donors/a-52022245

- On the moral admissibility of the voluntary supply of organs, whether free or not, see Garzón Valdés, Ernesto. “Some ethical considerations about organ transplantation.” In: Vásquez, Rodolfo (compiler). Bioethics and law. Fundamentals and current problems. Mexico: Economic Culture Fund, 1999.

- Espinoza, Juan. Right of the People. Volume I. 6ª. Edition. Lima: Editora Jurídica Grijley, 2012: 328.

- Abellán, José Carlos and Lopez Barahona, Mónica. The codes of life. Madrid: Homolegens; 2009.

- Thaler, Richard. Everything I have learned with economic psychology. The encounter between economics and economic psychology. The meeting between economics and psychology and its implications for individuals. Barcelona: Deusto, 2016:197.

- Sunstein, Cass and Thaler, Richard. A little push (Nudge). 2a. reprint. Madrid: Penguim Random House Editorial Group. 2018: 207.

- World Medical Association (WMA). WMA Declaration on Organ and Tissue Donation. Published on July 20, 2022. Accessed August 16, 2024. https://www.wma.net/es/policies-post/declaracion-de-la-amm-sobre-la-donacion-de-organos-y-tejidos/

- Moreu Carbonell, Elisa. Nudges and public law. Opportunity and regulation. In: Ponce Solé, Julio (Coordinator). Nudges, good government and good administration. Contributions from behavioral sciences, nudging and the public and private sector. Madrid: Marcial Pons, Legal and Social Editions, 2022: 98.

- Cárdenas Krenz, R. “Individual freedom vs. the common good? Lessons from the pandemic and nudges as a vaccination strategy”. 1st Edition, Galicia: Editorial Colex, S.L. 2024: 146-147.

- Sunstein, Cass and Thaler, Richard. A little push (Nudge). 2a. reprint. Madrid: Penguim Random House Editorial Group. 2018: 203 et seq.

- Martínez Palomo, Adolfo (compiler). Bioethics: in search of consensus on consent. Mexico: El Colegio Nacional, 2009:15.