Sustainable Practices in Extracorporeal Organ Support

Extracorporeal Organ Support Sustainability: Greener as a Clinical Outcome

Maria-Jimena Muciño-Bermejo1,2

- International Renal Research Institute of Vicenza (IRRIV) Vicenza, Italy

- The American British Cowdray Medical Center. Mexico City, Mexico.

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: 31 May 2025

CITATION: Muciño-Bermejo, M., 2025. Extracorporeal organ support sustainability: Greener as a clinical outcome. Medical Research Archives, [online] 13(5). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i5.0000

COPYRIGHT © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i5.0000

ISSN 2375-1924

ABSTRACT

In the last 150 years, healthcare has become a large scale multidisciplinary human activity that involves the interaction of social, technological, legal, political, and economical issues. To be highlighted, healthcare may represent 4.6% to 8.5% of worldwide greenhouse gas emissions. Extracorporeal organ support, one of the most life-saving interventions in emergency and critical care medicine, represents a sustainability challenge because of the amount of resources needed for every single patient and the increasing number of expected cases in the years to come. Given that the conservation of essential resources for human life relies on the sustainability of each and all of the human activities, the development of greener healthcare policies regarding extracorporeal life support has been recognized to be of utmost importance. Systematic, organized research should be implemented in order to establish evidence based standardized, large scale guidelines and procedures aimed not only improve survival of patients, but to ensure sustainability. Of note, the place and window of opportunity that extracorporeal organ support represent towards a greener global healthcare remains to be fully described. Most probably, within the following years, extracorporeal organ support will represent an inflexion point into diminishing the use of further healthcare resources (i.e. early home-based ultrafiltration may preventing recurrent hospital admissions because of decompensated hearth failure). The present manuscript is aimed to summarize the importance, challenges and current perspectives on the way to achieve sustainability of extracorporeal organ support.

Keywords: Extracorporeal Organ support, multiorgan failure, sustainability, public healthcare, environmental ethics.

Introduction

Historically, medical interventions belonged to a private, personal space between the patient and their physician, with the rise in life expectancy and world population initiated in 1700 rather attributable to economic and social changes than medical advances itself, as stated by the Thomas McKeown analysis. However, it should be taken into account that such advances were given also because of the parallel existence of redistributive social philosophy and large scale public health policies. With the advent of industrial revolution, technological boost gave place to a giant step in medical knowledge, and a bidirectional effect of industrialization on human health was established:

- The development of new insights in chemistry and engineering led to the invention of machines, new energy sources, materials and factory systems allowing medical science to advance, developing medical instruments, biochemical markers of health, pharmacology and public health policies.

- At the same time, overcrowding, pollution, trauma and large scale healthcare policies creation delay gave place to an increase in mortality.

Within this framework, it is important to notice that increase in mortality associated with infectious disease, occupational hazards, poor housing and pollution were not inevitable consequences of large scale industrialization, but rather a reflect of the lacking of public health policies that regulates logical consequences of industrial development. Ever since the industrial revolution, every new medical advance has posed a special challenge regarding sustainability policies: from protective equipment after the discovery of X rays to reasonable antibiotic regimens to avoid widespread antibiotic resistance: from security measures after the invention of anesthetic gases to recycling policies after the invention of plastics. Being a complex, “high resource consumption” medical intervention, the diagnostic-therapeutic approach to the patient with extracorporeal organ support (ECOS), may include nearly every described medical maneuver, from medical-grade plastics use to bedside surgical procedures. Plus, the historical framework in which ECOS is involved, in which global warming is already a global emergency, makes the development of sustainable ECOS practices a multidimensional challenge and bioethical duty to be taken as a priority in terms of clinical medicine, public healthcare, economy and engineering.

Definition and Bioethics of Sustainability

Being the “do no harm” (nonmaleficence) principle a cornerstone in the medical practice, to ensure the conservation of the natural resources for human life should be one of the primary considerations in the everyday practice. For instance, ensuring preservation of natural resources has become an everyday ethical duty of healthcare personnel, from rationale use of water to avoiding medical futility and therapeutic obstinacy. When it comes to larger scale decision making, however, clinical guidelines and public health policy design implies special ethical considerations. Being access to healthcare an essential, universal human right, ensuring equitable access to healthcare to all of the present generation, as well as generational commitment to sustainability as per the Brundtland Report in 1987, essential questions must be considered regarding ECOS, an intense resource consuming therapeutic option, including, but not limited to:

- Which variables should be used as a surrogate marker of sustainability?

- Which variables should be chosen (or designed) to measure the ecological cost/effect?

- Which environmental/public health policies should be implemented to minimize/retribute the ecological cost?

- Which prospective economical measures should be used to ensure the access to ECOS in the context of a large scale increase in ECOS need (i.e. global pandemics)?

ECOS Sustainability within Healthcare.

In order to achieve ECOS sustainability, the abstract concept, operational definition and applicability of sustainability itself must be stated. Defined as the ability to maintain or support a process continuously over time, sustainability has 3 pillars: environmental, social and economic, and the internal structure of sustainability includes policies, procedures, and oversight structures that ensures sustainability goals. Thus, the core of sustainability of ECOS itself remains in the implementation of Evidence based interventions (EBIs) in every step related to it, from prevention of ECOS need to ensuring access to ECOS to the future generations. Of note, long term sustainability of ECOS should not be limited to medical/technical issues, such as diminishing waste generation or water usage, but ensuring a multidimensional perspective that includes the 4 P’s of sustainability: people (the impact on all of the persons involved) planet (the impact on ecology) profit (i.e. economic efficiency, quality-adjusted life years) and purpose. Just as any other human activity, healthcare has an important environmental impact, that paradoxically contribute to the adverse clinical consequences for human health; Climate change has been described to be responsible for 400,000 additional deaths yearly, and it is prospected to reach 700,000 deaths each year by 2030. Changes in climate patterns lead to more frequent and more extreme weather events, natural, and socioeconomic disasters that increase health care resources need, leading to health systems overload. Climate hazards, amplified by socioeconomic vulnerability can give place adverse public health scenarios.

In continuous with what it was noticed since the very beginning of the industrial revolution, the mechanisms by which climate change leads to adverse health outcomes include increased risk of metabolic, respiratory, endocrine, neurological and oncologic diseases related to air pollution, and increased risk of infectious disease due to changes in the environmental factors affecting biological vectors and microbial change. In order to objectively measure and compare the ecological impact of a given process, standardized methods have been developed, including life cycle assessment and carbon footprint. Life cycle assessment (LCA) measures the environmental impact of a product from production to waste or recycling (cradle-to-grave) across five phases: Raw material extraction, manufacturing/processing, transportation, usage/retail and waste/disposal. Carbon footprint is defined as the total amount of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions directly and indirectly caused by the activities of an entity, either human or organization, and its calculated as the sum of resources involved including:

- Transport

- Food and household

- Phone and internet

- Recycling

- Electricity

- Water

- Waste

- Gas: (H2O, CFCs, CO2, N2O, CH4)

Thus, carbon footprint has become an important issue to take into account when planning medical programs, as healthcare is described to contribute with 4-4.4% of worldwide GHG emissions and similar fractions of toxic air pollutants. Described strategies to reduce carbon footprint applicable to any human action include the well-known “reduce, reuse, recycle” formula that may include, when applied to healthcare:

| Strategies |

|---|

| Diminishing electricity usage, such as the air conditioner of rooms, unplugging electrical device non in usage and using as much as natural light as possible. |

| Reducing the need for transportation. |

| Reduce on-paper printing, as well as preferring automatic two sided printing. |

| Reducing the waste, including diminishing usage of single-use plastic use and single-use items. |

Within the frame of healthcare, sustainability can be defined as the practice of providing health care excellence while reducing its environmental impact, being its principles sustainable prevention and pathways (i.e. streamlining systems that avoid duplication of care), being community-focused, eco-friendly and cost-efficient.

Challenges Towards ECOS Sustainability

Being one of the most life-saving interventions in emergency and critical care, ECOS has developed rapidly in the last 100 years: Based on the theories from Graham, RRT has become available since the 1950’s, with intermittent modalities for chronic patients available from the 1960’s, the treatment of fluid overload via ultrafiltration and continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) from the 1970’s and slow extended daily dialysis (SLEDD) since the 1990’s. Gibbon used artificial oxygenation and perfusion support for the first successful open-heart surgery in 1953, and in the 1960’s, Kolobow designed an alveolar membrane artificial heart lung, settling the basis for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), first used by Hill in 1972. Based on the aforementioned technology, liver-support albumin-based dialysis was proposed, and CO2 removal devices employing membrane oxygenators and sorbent therapies became available. Even when designed in parallel, but not initially intended to work in a single patient at the same time, later on it became clearer that an organ failure is rarely a single organ failure. Considering multiple interactions between native organs (“crosstalk”), combined and/or integrated extracorporeal organ support (ECOS) devices were designed, with the concept of multiple organ support therapy (MOST) being described by Ronco and Bellomo. Being renal replacement therapy (RRT) principles the foundation of subsequent forms of ECOS, many of the challenges towards ECOS sustainability have already been approached within the frame of RRT and/or other critical care medicine scenarios.

The priority of reducing the incidence of organ failure cases needing ECOS, may be best understood in the scope of the epidemiological trends:

- Overt organ dysfunction affects up to 70% of patients during their ICU stay.

- As much as 50-60% of patients admitted to the ICU, will develop AKI, and among them 10-15% will require RRT. Moreover, about 30% of patients with AKI may require chronic dialysis after discharge.

- On the other hand, the difficulties developing a sustainable program were highlighted in the course of both 2009 influenza and 2019 COVID-19 pandemics, as stated by the American Hospital Associations.

- The expectable amount of human, economic and material resources expected to be needed can be understood when getting in perspective than, in less than 100 years, ECOS has evolved from anecdotal cases of a single kind of therapy to worldwide use of multiple techniques including ultrafiltration, extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, hemodialysis, albumin techniques, plasma exchange, hemoadsoption, plasma exchange and bioartificial systems. Moreover, in the years to come extended number of indications and worldwide peaks on its usage are expected in the years to come.

Efforts to assess and improve the ecological impact of ECOS already in progress include to find standardized methods to measure and compare the ecological impact of ECOS:

The carbon footprint of Hemodialysis per year is 3.8-10.2 tons CO2e; Recently, a metric called “Mortality Cost of Carbon” has been developed to measure the impact of carbon emissions in the form of excess deaths. In 2023 European Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care (ESAIC) adopted the Glasgow Declaration and stated forward recommendations in four main areas: direct emissions, energy, supply chain and waste management, as well as psychological and self-care of healthcare professionals. Recommendations included the use of very low fresh gas flow, choice of anaesthetic drug, energy and water saving. Even if when all of the different indications, scenarios and ECOS modalities belongs to very different clinical entities, when it comes to assessing sustainability, common strategies, perspectives, approaches and policies may be applied.

Optimizing waste management is one of the main areas of opportunity in the way to ECOS worldwide sustainability. Just as the Law of conservation of mass in the nature ensure circular cycles regarding organic matter, cradle-to-cradle design for technological assets must be rethought in the sight of developing easy to reuse, reduce and recycle equipment. In a yearly ICU material flow analysis (MFA) performed in 2019, it was reported the generation of a material mass inflow of 247,000 kg, out of which 50,000 kg were incinerated as hazardous hospital waste, with an environmental impact per patient of 17 kg of mass, 12 kg of CO2 equivalents 300 L of water usage and 4 meter2 of agricultural land occupation daily. Regarding waste production in the ICU, 5 hotspots have been identified: non sterile gloves, isolation gowns, bed liners, surgical mask and syringes, thus personal protective equipment, syringes with packaging, sterile water and bedliners are responsible for 20% of the ICU material use. Of interest, the packaging of tissues and compresses has a very high product/package relationship. From this data, one of the main factors to be taken home is that improving the human process linked to the generation of waste may be one of the keys to sustainable ECOS.

During each HD session, up to 1.5 to 8 Kg of mainly plastic waste, are generated, corresponding to an annual worldwide production of 1.2 million tons; For infectious waste, almost entirely managed by incineration, it is desirable for the use of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) to be replaced by chlorine-free polymers; this reduces the formation of dioxins and furans, which are generated at insufficiently high temperatures. Also, optimizing hemofilters by adding a coating agent to haemofilters may reduce the incidence of thrombosis of the haemofilter, subsequently reducing the number of filters wasted. Many manufacturers have optimized the device design to make it more eco-friendly. Modifications include reduction of disposable weight by implementing an all-in-one cassette system that unifies all the components of the extracorporeal circuit. The use of lighter material, such as polyolefines reduces the weight of the unused disposable. Performing on-line priming and rinsing in the set-up phase, and on-line infusions and reinfusion at the end of the session, instead of applying saline from an extra bag, reduces disposable weight generated at every session: this highlight the importance of optimizing human process in order to improve sustainability. Increasing the recyclability (defined as the ability of a material or product to be collected, processed, and reused) has also been studied as a mean to improve the sustainability of ECOS: from achieving the maximum catalytic efficiency to the employment of specific materials to the development of green functionalized nanomaterials, including bioplastics to green functionalized nanomaterials designed specially to be renewable, eco-friendly and energetically efficient. Expected benefits of green nanotechnology include increased energy efficiency, reduced waste and GHG, and minimized consumption of nonrenewable raw materials.

Very importantly, the definition and search for “best available technique” for a given episode (i.e. the one that gets the maximum clinical benefit at the lowest ecological cost), from choosing between two similar techniques (i.e. Mars vs. Prometheus) to combining different techniques in a single patient (i.e. Peritoneal dialysis and HD, as described for Japanese elderly people) to the development of bioartificial organs. Among the few described options for water saving in ECOS, water used for dialysis, pretreated with reverse osmosis, could be used for flushing toilets, washing or even soil fertilization, since nearly 100% of phosphate and 25% of ammonia can be recovered from this wastewater. Additionally, a reduction of Qd from 500 to 400 mL/min could save about 24 L of water during 4-h standard hemodialysis session, that implies the saving of 3744 liters yearly. On a world scale, it would mean conserving 24 billions liters of water daily. Even if this change cannot be made to a greater scale, but on a case-by-case decision making, in order to preserve KT/V, a Qd reduction to 400mL/min may not affect dialysis efficacy. Of note, among the three options for dialysate in the market (liquid concentrated delivered in plastic containers, and powder for dilution) significant differences in ecological exist, being the powder or semidry concentrate the most ecological option, as it implies less transportation cost, less plastic waste and less storage space needed. Ecological analysis of consumables option should be done on the everyday basis for ECO options.

Utilizing renewable energy sources including solar panels, geothermal energies and eolic energy, and diminishing as much as possible both thermal and electrical requirements of HD facilities. Described strategies for diminishing energy consumption include use of technologies to manage electrical loads (i.e. variable intensity drives), infrastructural measures such as thermal insulation and energy monitoring systems, and training both patients and medical personnel in energy-saving strategies.

Discussion

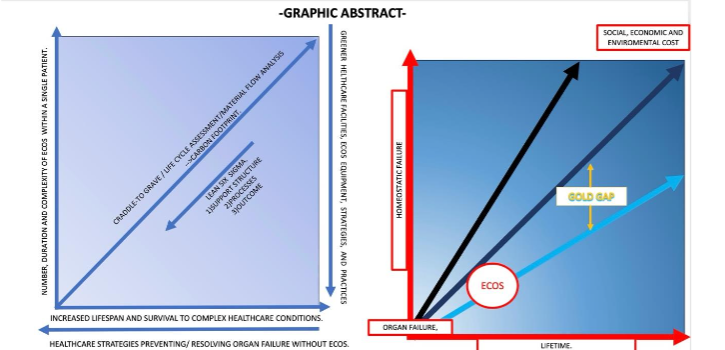

Global warming is an urgent reality nowadays, especially if the increase rate in human population is taken into account; in 1800, the world population was 1 billion people, and the global population today surpasses 8 billions. This increase is not only related to increase birth rate, both, from the 19th century, the infant mortality reduction and extended life spam. As worldwide population increases, the development of human activities without a sustainability perspective deteriorates the global environment by breaking the “circular economy” of natural ecosystems and, consequently, deteriorates human life. These phenomena have been already anticipated by academics focused on the process of evolution, species development, symbiosis and economic development, including Darwin, Spencer, Kropotkin and Malthus. From this perspective, any human activity could adversely affect the ecological balance. Healthcare has become a multidisciplinary system that involves technological, social, legal political, and economical interactions. Recently, it has been recognized that healthcare ecological and environmental interactions are also crucial, since the conservation of essential resources and adequate media for human life relies on the sustainability of each and all of the human activities, including healthcare itself. Furthermore, it has been proposed that “health is a state of complete physical, mental, social and ecological well-being and not merely the absence of disease—personal health involves planetary health”. As every large scale human activity, health care contributes to global warming, representing as much as 4-4.4% of worldwide GHG and toxic air pollutants. Among the different therapeutic interventions, ECOS deserve special attention because of its expected benefit as a therapeutic maneuver, high resource need and the expected increase in need for ECOS as human survival increases. On the way of reducing environmental impact, the use of standardized measures, including Life cycle assessment, Carbon footprint and Mortality Cost of Carbon may be useful to assess and compare the impact of different strategies aimed to improve sustainability of RRT. As carbon footprint of CKD care increases as GFR diminished, strategies aimed focused on primary, secondary and tertiary prevention may improve the RRT burden. Just as in any other process, modifications focused on sustainability are based on the “reduce, recycle, reuse” approach in order to attain a nearly perfect “circular economy” or a zero carbon print in the process of a given medical interventions. Most importantly, until now, sustainability approaches to ECOS have been based on a “damage limit/lesser harm” politics, but the main place of ECOS within global healthcare sustainability may be the creation of an inflexion point, preventing further health related resource consumption, creating a “golden gap” in terms of diminishing the prospected use of health resources within an individual lifespan. For doing so, a “greater good” bioethics approach must be added to the overall ECOS sustainability analysis, as it is not mutually excluding, but complementary with a “damage limiting” perspective. For doing so, important questions remains to be routinely made:

- Does a given ECOS option is significantly greener than other, for a given clinical benefit?

- Does ECOS may prevent for health related expenses (i.e. UF preventing hospital admission for decompensated heart failure)?

- Does ECOS as a bridge to transplant may prevent an individual to became chronically critically ill?

- Does early ECOS may prevent organ failure progress? Can it prevent a single organ failure progress to multiple organ failure?

Within the years to come, standardized clinical outcomes and trials may be designed to answer this questions. Additionally, the technological progress may allow not only greener, but also earlier approaches to organ failure support, making ECOS more of an organ preserving/ future resource saving therapy.

Conclusions

As the complexity of medical cases increases (along with the increased life expectancy and increased survival from previously considered lethal diseases), intensive care medicine, particularly ECOS has become a nearly everyday part of the medical practice in specialized medical facilities, making the creation of ECOS sustainability policies that involves social, economical, human and environmental issues a priority. Primary and secondary prevention of organ failure in the outpatient setting and medical algorithms for early detection of organic failure within the context of in-hospital care are key components for attaining long term sustainability of ECOS, as it decreases incidence of ECOS need. Until now, improving the everyday medical care practices, water reuse, efficient use of plastics and selection of the most cost/effective ECOS strategy within a single patient are the key components to reduce social, economic an environmental impact of ECOS therapy. Future directions towards ECOS sustainability includes the creation of new biomaterials, bioartificial organs, miniaturization and simplification of ECOS equipment in order to achieve easier, ambulatory supervised (and possibly artificial intelligence assisted) patient-operable long-term ECOS. Of note, the addition of a “greater good” bioethical approach to ECOS use may allow it to become a healthcare resource saving therapy.

References

- Colgrove J. The McKeown thesis: a historical controversy and its enduring influence. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(5):725-729. doi:10.2105/ajph.92.5.725.

- Szreter S. Rethinking McKeown: the relationship between public health and social change. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(5):722-725. doi:10.2105/ajph.92.5.722.

- Crane-Kramer G, Buckberry J. Changes in health with the rise of industry. Int J Paleopathol. 2023;40:99-102. doi:10.1016/j.ijpp.2022.12.005.

- Romanello M, McGushin A, Di Napoli C, et al. The 2021 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: code red for a healthy future [published correction appears in Lancet. 2021 Dec 11;398(10317):2148. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02429-6.]. Lancet. 2021;398(10311):1619-1662. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01787-6.

- Richie C. A brief history of environmental bioethics. Virtual Mentor. 2014;16(9):749-752. Published 2014 Sep 1. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2014.16.09.mhst2-1409.

- Calderon PEE, Tan MKM. Care for the Environment as a Consideration in Bioethics Discourse and Education. New Bioeth. 2023;29(4):352-362. doi:10.1080/20502877.2023.2219021

- Richie C. Guest Editorial: Sustainability and bioethics: where we have been, where we are, where we are going. New Bioeth. 2020;26(2):82-90. doi:10.1080/20502877.2020.1767920.

- Grinberg AR, Tripodoro VA. Futilidad médica y obstinación familiar en terapia intensiva. ¿Hasta cuándo seguir y cuándo parar? [Medical futility and family obstinacy in intensive therapy. When to stop and when to keep going?]. Medicina (B Aires). 2017;77(6):491-496.

- Rigaud JP, Giabicani M, Beuzelin M, Marchalot A, Ecarnot F, Quenot JP. Ethical aspects of admission or non-admission to the intensive care unit. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5(Suppl 4):S38. doi:10.21037/atm.2017.06.53.

- Takala T, Häyry M. Justainability. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. Published online June 27, 2023. doi:10.1017/S0963180123000361.

- Thomas J, Mantri P. Design for financial sustainability. Patterns (N Y). 2022;3(9):100585. Published 2022 Sep 9. doi:10.1016/j.patter.2022.100585.

- Shelton RC, Hailemariam M, Iwelunmor J. Making the connection between health equity and sustainability. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1226175. Published 2023 Sep 26. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1226175.

- Hailemariam M, Bustos T, Montgomery B, Barajas R, Evans LB, Drahota A. Evidence-based intervention sustainability strategies: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):57. Published 2019 Jun 6. doi:10.1186/s13012-019-0910-6

- Bodkin A, Hakimi S. Sustainable by design: a systematic review of factors for health promotion program sustainability. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):964. Published 2020 Jun 19. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09091-9.

- Gusmão Louredo FS, Raupp E, Araujo CAS. Meaning of sustainability of innovations in healthcare organizations: A systematic review. Health Serv Manage Res. 2024;37(1):16-28. doi:10.1177/09514848231154758.

- Chalil Madathil K, Greenstein JS. Designing comprehensible healthcare public reports: An investigation of the use of narratives and tests of quality metrics to support healthcare public report sensemaking. Appl Ergon. 2021;95:103452. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2021.103452

- Read J, Meath C. A Conceptual Framework for Sustainable Evidence-Based Design for Aligning Therapeutic and Sustainability Outcomes in Healthcare Facilities: A Systematic Literature Review. HERD. 2025;18(1):86-107. doi:10.1177/19375867241302793.

- Kim Y, Kim Y, Lee HJ, et al. The Primary Process and Key Concepts of Economic Evaluation in Healthcare. J Prev Med Public Health. 2022;55(5):415-423. doi:10.3961/jpmph.22.195.

- McKinnon M. Estudios Gráficos Europeos, SA; Spain: 2012. Climate Vulnerability Monitor: A Guide to the Cold Calculus of a Hot Planet; p. 331

- Zhao Q, Yu P, Mahendran R, et al. Global climate change and human health: Pathways and possible solutions. Eco Environ Health. 2022;1(2):53-62. Published 2022 May 7. doi:10.1016/j.eehl.2022.04.004.

- Semenza JC, Rocklöv J, Ebi KL. Climate Change and Cascading Risks from Infectious Disease. Infect Dis Ther. 2022;11(4):1371-1390. doi:10.1007/s40121-022-00647-3.

- Chen J, Hoek G. Long-term exposure to PM and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Int. 2020;143:105974. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2020.105974.

- Cavicchioli R, Ripple WJ, Timmis KN, et al. Scientists’ warning to humanity: microorganisms and climate change. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17(9):569-586. doi:10.1038/s41579-019-0222-5.

- McGain F, Muret J, Lawson C, Sherman JD. Environmental sustainability in anaesthesia and critical care. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125(5):680-692. doi:10.1016/j.bja.2020.06.055.

- Nagai K, Suzuki H, Ueda A, Agar JWM, Itsubo N. Assessment of environmental sustainability in renal healthcare. J Rural Med. 2021;16(3):132-138. doi:10.2185/jrm.2020-049.

- The Lancet Digital Health. Curbing the carbon footprint of health care. Lancet Digit Health. 2023;5(12):e848. doi:10.1016/S2589-7500(23)00229-7

- Lenzen M, Malik A, Li M, et al. The environmental footprint of health care: a global assessment. Lancet Planet Health. 2020;4(7):e271-e279. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30121-2.

- Monteiro S, Nuno Lopes MJ, Barata Coutinho AP. EcoHealth Center: reduce, reuse, recycle!. Rural Remote Health. 2023;23(1):8178. doi:10.22605/RRH8178.

- Ang TL, Choolani M, Poh KK. Healthcare and environmental sustainability. Singapore Med J. 2024;65(4):203. doi:10.4103/singaporemedj.SMJ-2024-068.

- Knagg R, Dorey J, Evans R, Hitchman J. Sustainability in healthcare: patient and public perspectives. Anaesthesia. 2024;79(3):278-283. doi:10.1111/anae.16159.

- Huber W, Ruiz de Garibay AP. Options in extracorporeal support of multiple organ failure. Optionen der extrakorporalen Unterstützung bei Multiorganversagen. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed. 2020;115(Suppl 1):28-36. doi:10.1007/s00063-020-00658-3.

- Ranieri VM, Brodie D, Vincent JL. Extracorporeal Organ Support: From Technological Tool to Clinical Strategy Supporting Severe Organ Failure. JAMA. 2017;318(12):1105-1106. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.10108.

- Ronco C. Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy: Forty-year Anniversary. Int J Artif Organs. 2017;40(6):257-264. doi:10.5301/ijao.5000610.

- Burchardi H. History and development of continuous renal replacement techniques. Kidney Int Suppl. 1998;66:S120-S124.

- Ronco C, Ricci Z, Husain-Syed F. From Multiple Organ Support Therapy to Extracorporeal Organ Support in Critically Ill Patients. Blood Purif. 2019;48(2):99-105. doi:10.1159/000490694.

- Papamichalis P, Oikonomou KG, Xanthoudaki M, et al. Extracorporeal organ support for critically ill patients: Overcoming the past, achieving the maximum at present, and redefining the future. World J Crit Care Med. 2024;13(2):92458. Published 2024 Jun 9. doi:10.5492/wjccm.v13.i2.92458.

- Stolldorf DP. Sustaining Health Care Interventions to Achieve Quality Care: What We Can Learn From Rapid Response Teams. J Nurs Care Qual. 2017;32(1):87-93. doi:10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000204.

- https://www.fda.gov/media/124716/download access April 1st, 2025.

- Perez Ruiz de Garibay A, Kortgen A, Leonhardt J, Zipprich A, Bauer M. Critical care hepatology: definitions, incidence, prognosis and role of liver failure in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2022;26(1):289. Published 2022 Sep 26. doi:10.1186/s13054-022-04163-1.

- Montini L, Antonelli M. Multiple organ failure: incidence and outcomes over time. Minerva Anestesiol. 2021;87(2):139-141. doi:10.23736/S0375-9393.21.15446-X.

- Jansson MM, Ohtonen PP, Syrjälä HP, Ala-Kokko TI. Changes in the incidence and outcome of multiple organ failure in emergency non-cardiac surgical admissions: a 10-year retrospective observational study. Minerva Anestesiol. 2021;87(2):174-183. doi:10.23736/S0375-9393.20.14374-8.

- Herrera-Gutiérrez ME, Seller-Pérez G, Sánchez-Izquierdo-Riera JA, Maynar-Moliner J; COFRADE investigators group. Prevalence of acute kidney injury in intensive care units: the “COrte de prevalencia de disFunción RenAl y DEpuración en críticos” point-prevalence multicenter study. J Crit Care. 2013;28(5):687-694. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.05.019.

- Wahrhaftig Kde M, Correia LC, de Souza CA. Classificação de RIFLE: análise prospectiva da associação com mortalidade em pacientes críticos [RIFLE Classification: prospective analysis of the association with mortality in critical ill patients] [published correction appears in J Bras Nefrol. 2013 Jan-Mar;35(1):77]. J Bras Nefrol. 2012;34(4):369-377. doi:10.5935/0101-2800.20120027.

- Hsu RK, McCulloch CE, Dudley RA, Lo LJ, Hsu CY. Temporal changes in incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(1):37-42. doi:10.1681/ASN.2012080800.

- Rewa OG, Ortiz-Soriano V, Lambert J, et al. Epidemiology and Outcomes of AKI Treated With Continuous Kidney Replacement Therapy: The Multicenter CRRTnet Study. Kidney Med. 2023;5(6):100641. Published 2023 Apr 15. doi:10.1016/j.xkme.2023.100641.

- Dahlerus, C., Segal, J. H., He, K., Wu, W., Chen, S., Shearon, T. H., Sun, Y., Dahlerus C, Segal JH, He K, et al. Acute Kidney Injury Requiring Dialysis and Incident Dialysis Patient Outcomes in US Outpatient Dialysis Facilities. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;16(6):853-861. doi:10.2215/CJN.18311120.

- Liyanage T, Ninomiya T, Jha V, et al. Worldwide access to treatment for end-stage kidney disease: a systematic review. Lancet. 2015;385(9981):1975-1982. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61601-9.

- https://www.aha.org/webinars/2020-03-26-ecmo-insights-strategies-and-key-considerations-developing-sustainable-program. Accessed April 1st, 2025.

- Gaetani M, Uleryk E, Halgren C, Maratta C. The carbon footprint of critical care: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2024;50(5):731-745. doi:10.1007/s00134-023-07307-1.

- Bhopal A, Sharma S, Norheim OF. Balancing the health benefits and climate mortality costs of haemodialysis. Future Healthc J. 2023;10(3):308-312. doi:10.7861/fhj.2022-0127.

- Gonzalez-Pizarro P, Brazzi L, Koch S, et al. European Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care consensus document on sustainability: 4 scopes to achieve a more sustainable practice. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2024;41(4):260-277. doi:10.1097/EJA.0000000000001942.

- Piccoli GB, Nazha M, Ferraresi M, Vigotti FN, Pereno A, Barbero S. Eco-dialysis: the financial and ecological costs of dialysis waste products: is a ‘cradle-to-cradle’ model feasible for planet-friendly haemodialysis waste management. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30(6):1018-1027. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfv031.

- Hunfeld N, Diehl JC, Timmermann M, et al. Circular material flow in the intensive care unit-environmental effects and identification of hotspots. Intensive Care Med. 2023;49(1):65-74. doi:10.1007/s00134-022-06940-6.

- James R. Incineration: why this may be the most environmentally sound method of renal healthcare waste disposal. J Ren Care. 2010;36(3):161-169. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6686.2010.00178.x.

- Tagaya M, Hara K, Takahashi S, et al. Antithrombotic properties of hemofilter coated with polymer having a hydrophilic blood-contacting layer. Int J Artif Organs. 2019;42(2):88-94. doi:10.1177/0391398818815480.

- Gauly A, Fleck N, Kircelli F. Advanced hemodialysis equipment for more eco-friendly dialysis. Int Urol Nephrol. 2022;54(5):1059-1065. doi:10.1007/s11255-021-02981-w.

- Wieliczko M, Zawierucha J, Covic A, Prystacki T, Marcinkowski W, Małyszko J. Eco-dialysis: fashion or necessity. Int Urol Nephrol. 2020;52(3):519-523. doi:10.1007/s11255-020-02393-2.

- Chaudhary RG, Desimone MF. Synthesis, Characterization, and Applications of Green Synthesized Nanomaterials (Part 1). Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2021;22(6):722-723. doi:10.2174/138920102206210521165455.

- Gadour E, Kaballo MA, Shrwani K, et al. Safety and efficacy of Single-Pass Albumin Dialysis (SPAD), Prometheus, and Molecular Adsorbent Recycling System (MARS) liver haemodialysis vs. Standard Medical Therapy (SMT): meta-analysis and systematic review. Prz Gastroenterol. 2024;19(2):101-111. doi:10.5114/pg.2024.139297

- Nagai K. Possible benefits for environmental sustainability of combined therapy with hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis in Japan. Front Nephrol. 2024;4:1394200. Published 2024 Nov 14. doi:10.3389/fneph.2024.1394200.

- De Bartolo L, Mantovani D. Bioartificial Organs: Ongoing Research and Future Trends. Cells Tissues Organs. 2022;211(4):365-367. doi:10.1159/000518251.

- Ekins P, Zenghelis D. The costs and benefits of environmental sustainability. Sustain Sci. 2021;16(3):949-965. doi:10.1007/s11625-021-00910-5.

- Tarrass F, Benjelloun H, Benjelloun M. Nitrogen and phosphorus recovery from hemodialysis wastewater to use as an agricultural fertilizer. Nefrologia (Engl Ed). 2023;43 Suppl 2:32-37. doi:10.1016/j.nefroe.2023.05.007.

- Alayoud A, Benyahia M, Montassir D, et al. A model to predict optimal dialysate flow. Ther Apher Dial. 2012;16(2):152-158. doi:10.1111/j.1744-9987.2011.01040.x.

- Molano-Triviño A, Wancjer B, Neri MM, Karopadi AN, Rosner M, Ronco C. Blue Planet dialysis: novel water-sparing strategies for reducing dialysate flow. Int J Artif Organs. Published online November 8, 2017. doi:10.5301/ijao.5000660.

- Zawierucha J, Marcinkowski W, Prystacki T, et al. Green Dialysis: Let Us Talk about Dialysis Fluid. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2023;48(1):385-391. doi:10.1159/000530439.

- Čongradac V, Prebiračević B, Jorgovanović N, Stanišić D. Assessing the energy consumption for heating and cooling in hospitals. Energy and Buildings 2012;48:146-154. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2012.01.022

- Piccoli GB, Cupisti A, Aucella F, et al. Green nephrology and eco-dialysis: a position statement by the Italian Society of Nephrology. J Nephrol. 2020;33(4):681-698. doi:10.1007/s40620-020-00734-z.

- Rathore SS, Nirja K, Choudhary S, Jeswani G. Green Dialysis From the Indian Perspective: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2024;16(6):e62876. Published 2024 Jun 21. doi:10.7759/cureus.62876.

- Eastwood MA. Global warming and the laws of nature. QJM. 2021;114(4):227-228. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcaa152.

- https://ourworldindata.org/population-growth, accessed September 29, 2024.

- Prescott, S.L.; Logan, A.C.; Albrecht, G.; Campbell, D.E.; Crane, J.; Cunsolo, A.; Holloway, J.W.; Kozyrskyj, A.; Lowry, C.A.; Penders, J.; et al. The Canmore Declaration: Statement of Principles for Planetary Health. Challenges 2018, 9, 31

- The Lancet Planetary Health. Education for planetary health. Lancet Planet Health. 2023;7(1):e1. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00338-2.

- Lenzen M, Malik A, Li M, et al. The environmental footprint of health care: a global assessment. Lancet Planet Health. 2020;4(7):e271-e279. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30121-2.

- De Bartolo L, Mantovani D. Bioartificial Organs: Ongoing Research and Future Trends. Cells Tissues Organs. 2022;211(4):365-367. doi:10.1159/000518251.

- Chen M, Decary M. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: An essential guide for health leaders. Healthc Manage Forum. 2020;33(1):10-18. doi:10.1177/0840470419873123.

- Rivara MB, Himmelfarb J. From Home to Wearable Hemodialysis: Barriers, Progress, and Opportunities. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2024;19(11):1488-1495. doi:10.2215/CJN.0000000000000424.

- Mleyhi S, Ziadi J, Ben Hmida Y, Ghédira F, Ben Mrad M, Denguir R. La télémédecine et les réseaux sociaux dans la gestion des ECMO à l’ère de COVID-19 : l’expérience Tunisienne [Telemedicine and social Media in the management of ECMOs in the era of COVID-19: The Tunisian experience]. Ann Cardiol Angeiol (Paris). 2021;70(2):125-128. doi:10.1016/j.ancard.2020.12.004.

- Brunet J, Billaquois C, Viellard H, Courari F. Eco-friendly hospital architecture. J Visc Surg. 2024;161(2S):54-62. doi:10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2023.11.008

- Sá AGA, Laurindo JB, Moreno YMF, Carciofi BAM. Influence of Emerging Technologies on the Utilization of Plant Proteins. Front Nutr. 2022;9:809058. Published 2022 Feb 11. doi:10.3389/fnut.2022.809058.

- Gibas-Dorna M, Żukiewicz-Sobczak W. Sustainable Nutrition and Human Health as Part of Sustainable Development. Nutrients. 2024;16(2):225. Published 2024 Jan 10. doi:10.3390/nu16020225.

- See KC. Improving environmental sustainability of intensive care units: A mini-review. World J Crit Care Med. 2023;12(4):217-225. Published 2023 Sep 9. doi:10.5492/wjccm.v12.i4.217.

- Shrank WH, Rogstad TL, Parekh N. Waste in the US Health Care System: Estimated Costs and Potential for Savings. JAMA. 2019;322(15):1501-1509. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.13978.

- Barratt A, McGain F. Overdiagnosis is increasing the carbon footprint of healthcare. BMJ. 2021;375:n2407. Published 2021 Oct 4. doi:10.1136/bmj.n2407

- McGain F, Burnham JP, Lau R, Aye L, Kollef MH, McAlister S. The carbon footprint of treating patients with septic shock in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Resusc. 2018;20(4):304-312.

- Masud FN, Sasangohar F, Ratnani I, et al. Past, present, and future of sustainable intensive care: narrative review and a large hospital system experience. Crit Care. 2024;28(1):154. Published 2024 May 9. doi:10.1186/s13054-024-04937-9.

- Huffling K, Schenk E. Environmental sustainability in the intensive care unit: challenges and solutions. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2014;37(3):235-250. doi:10.1097/CNQ.0000000000000028.

- Zimmermann GDS, Bohomol E. Lean Six Sigma methodology to improve the discharge process in a Brazilian intensive care unit. Rev Bras Enferm. 2023;76(3):e20220538. Published 2023 Jul 10. doi:10.1590/0034-7167-2022-0538

- https://anzics.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/A-beginners-guide-to-Sustainability-in-the-ICU.pdf accessed April 18th, 2025.

- Soreze Y, Piloquet JE, Amblard A, Constant I, Rambaud J, Leger PL. Sevoflurane Sedation with AnaConDa-S Device for a Child Undergoing Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2020;24(7):596-598. doi:10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23487.

- Romagnoli S, Chelazzi C, Villa G, et al. The New MIRUS System for Short-Term Sedation in Postsurgical ICU Patients. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(9):e925-e931. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000002465.

- McGain F et al. (2020) Environmental sustainability in anaesthesia and critical care,” British Journal of Anaesthesia.125(5):680-692.

- Karimi K, Rahsepar M. Optimization of the Urea Removal in a Wearable Dialysis Device Using Nitrogen-Doped and Phosphorus-Doped Graphene. ACS Omega. 2022;7(5):4083-4094. Published 2022 Jan 24. doi:10.1021/acsomega.1c05495

- Barraclough KA, Agar JWM. Green nephrology. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16(5):257-268. doi:10.1038/s41581-019-0245-1.