Vaccination and SIDS: Mucosal vs. Systemic Immunity Insights

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome in the Context of the Future of Vaccination, and the Question of Systemic or Mucosal Immunity

Paul N. Goldwater1, Reginald M. Gorczynski2, Robyn A. Lindley3,4, Edward J. Steele5

- Paul N. Goldwater Adelaide Medical School, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, Adelaide University, Adelaide, SA, Australia.

- Reginald M. Gorczynski Institute of Medical Science & Departments of Immunology and Surgery, University of Toronto, Canada.

- Robyn A. Lindley Department Clinical Pathology, Victorian Comprehensive Cancer Centre (VCCC), University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia; GMDxgenomics, Suite 201, 697 Burke Rd, Camberwell, Melbourne, Australia

- Edward J. Steele Melville Analytics Pty Ltd and Immunomics, Brisbane, Australia.

OPEN ACCESS

PUBLISHED: June 30, 2025

CITATION:GOLDWATER, Paul N. et al. Sudden Infant Death Syndrome in the Context of the Future of Vaccination, and the Question of Systemic or Mucosal Immunity. Medical Research Archives, [S.l.], v. 13, n. 6, june 2025. Available at: <https://esmed.org/MRA/mra/article/view/6667>.

COPYRIGHT: © 2025 European Society of Medicine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v13i6.6667

ISSN 2375-1924

Abstract

We review the current knowledge regarding how best to approach development of lasting immunity in infancy without inducing unwanted adverse vaccine effects among which could be sudden infant death syndrome and neurological developmental problems. The review also addresses current problems in vaccine development generally including formulating infant vaccination schedules based on knowledge obtained in trials conducted in adults, a process so fundamentally flawed to warrant intense review. We explain the two key mechanisms by which the infant and adult human protects itself from foreign pathogens these being the very complex but integrated immune systems the Th1-based Mucosal Immune System and the Th2-based Systemic Immune System. The potential issue of hyperimmunization is discussed and the review addresses the latest developments that could provide a useful path to safer immunisation in infancy.

Keywords

- Sudden Infant Death Syndrome

- Vaccination

- Systemic Immunity

- Mucosal Immunity

- Hyperimmunization

Introduction

This is a critical yet selective review of the literature on the putative vaccine associated-causes of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). While it is recognised that this is a sensitive, complex and controversial subject it is important to accept that current immunisation approaches are fundamentally flawed. Much of the background to the complexity and controversy of vaccine safety and links to mortality is well covered. We therefore provide a comparative review of the function of the mucosal immune system in contrast to the distinctive and separate systemic immune system. The former is a body-wide interconnected lymphatic migration defending against the entry of viral, bacterial, fungal and protozoan pathogens at all internal-external mucosal secretory interfaces; the latter is fully activated into play when pathogens or their processed antigenic fragments actually enter into the internal body via a complex antigen drainage system of lymphatic ducts, nodes comprising the blood to lymph circulatory system, whereupon systemic specific immune responses are mobilised and launched.

This is the immune system as both the mucosal first line defence system and the systemic internal system act to defend the integrity of the body. In this paper we hope to arrive at practical generalisations that may contribute to the improved health of newborn babies, both physical and mental, as they develop through the first year of life and beyond to maturity.

Discussion

In our earlier review in this journal we built on the body of paediatric research on SIDS by one of us on the Infection of SIDS causation and/or association. We also drew attention to the strong positive correlation (linear regression) between the number of systemic (or parenteral) immunisation vaccine doses (intramuscular, subcutaneous) delivered in the first year of life and the rising incidence of SIDS in the top 30 to 46 developed nations surveyed with the best (lowest) infant mortality rates (IMRs) in 2009 and again in 2019. Given the regression was apparently independent of the variety of specific antigens injected we identified the potent non-specific cytokine-inducing systemic stimulation by the vaccine adjuvants as the main suspect in any likely search for the toxic ingredient that may be common to all strong systemic immunisations of infants. Thus, when we use the term hyperimmunization in later sections that would also include referral to repeated doses of alum-based adjuvants irrespective of antigen-specificity in the vaccine doses.

Thus, by drawing attention to the possible underlying immunological-driven causes of SIDS we also draw attention to potential downstream consequences on normal childhood development (in those babies that survive the first year of the childhood vaccine schedule). Here we take this analysis further and focus on the mucosal immune system as the preferred target for all future vaccines given to children and adults via the intranasal inhalation or application route of immunisation.

However, first, we need to deal with the protective and curative features of systemic immune responses which has a much longer history of scientific research and manipulation, dating to the 19th and early 20th century. This body of knowledge far exceeds our understanding of the behaviour of the mucosal immune system, which in relative terms, has been neglected in both the mainstream clinic and at the bench. It is also fair to say, as we point out, that the public health vaccine during the COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2 pandemic have brought this issue into sharp focus.

Features of systemic induced immunity, genetic individuality and systemic immune responses to external infections and internally arising cancers.

Anyone familiar with experimental and clinical immunology is struck by the immense biological complexity of the discipline, it rivals and is on par with the higher order complexity of the brain and central nervous system.

How is this immense complexity to be handled and understood? Few immunologists apart from Peter A. Bretscher have taken on this gargantuan task. It should be acknowledged his earlier late colleagues at the Salk Institute also took on aspects of this challenge – Melvin Cohn and Rod Langman. However, Bretscher’s unique body of work is far more comprehensive and fundamental, and he is now the acknowledged leading immunologist for his range, depth and reach in a very complex discipline drowning in, what he calls information overload thus crying out for a degree of systematic and rational order.

Since the mid-1960s Bretscher, in both his theoretical and experimental studies, has devoted his scientific career to bringing a semblance of rational order to the foundations of immunology. His most important experimental and observational studies focussed on chronic infectious diseases (induced immunity to viral, bacterial and protozoan parasites) and acquired immunity to endogenously arising cancers. His extensive body of work can be found in two recent easy to read textbooks published these past 10 years. It is the latter 2024 book and some of his key experimental and observational papers we cite here.

In our previous paper on the likely causes of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and how the phenomenon can be naturally suppressed we addressed the important role of Mucosal Immunity both active and passively provided in colostrum and milk of a breast-feeding mother (both germline-encoded Innate and somatic Adaptive immunity). We particularly stressed the protective role of acquired and adaptive mucosal dimeric secretory IgA antibodies, including maternal IgG antibodies. In the normal course of neonatal development these antibodies are naturally delivered to neonates via immunity arising from natural infections in the mother or via a systemically vaccinated breast-feeding mother. Local non-specific Innate Immunity to respiratory and gastrointestinal infections may also be induced in neonates through mucosal antigen exposure via the oral-nasal portal of entry (reviewed in Goldwater et al, 2025). We stressed that a functional mucosal immune system and its role in SIDS avoidance to distinguish it from the more familiar systemic or parenteral immunity of circulating immunoglobulin-secreting B lymphocytes producing serum antibodies (IgM, IgG subclasses, IgE, IgG4 and cell mediated T lymphocyte immunity (CD4+ T helper cells, delayed type hypersensitivity CD4+ T cells, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells).

The set of principles on the regulation of self versus non-self discrimination (how immunological self-tolerance is acquired in development, and thus the avoidance of self-reactive autoimmunity) and the regulation of the class of the immune response assembled by Bretscher pertain mainly to the Systemic Immune System and not, as we can ascertain to the Mucosal Activated Immune System, which we discuss again shortly (e.g. the recent data of Lobaina et al, 2024). However, the principles we now discuss in relation to vaccination risks in general and the risk of SIDS almost certainly apply. Hence, we also address whether the same principles of regulation by antigen dose for the initiation of the main helper T lymphocyte subsets Th1 and Th2 apply also to mucosal immunity and antigens that enter via the oral-nasal route?

At the mucosal lumen surface is it just non-complement fixing dimeric secretory IgA that is all that is required in protective adaptive mucosal immunity? Or is cell mediated immunity (CMI) also harnessed on the non-lumen internal side? Can foreign antigens (whether non-replicating or replicating that arrive via the oral-nasal route passively or actively) transit the mucosal membranes and enter the parenteral system thus initiating also induction of systemic Th1/Th2 regulated immunity?

In addition, it is useful to keep in mind the following categories of typical infectious diseases of epidemiologic and immunologic parameters of selected human respiratory viruses and vaccines used to control them and grouped by incubation time as in Table 1 above (from Morens et al, 2023). Thus, those with long incubation time (~ 10-16 days) and a strong viremic phase such as Measles, Mumps, Rubella, Smallpox, varicella-zoster virus (VZV) are distinct from the short incubation time (~ 2-5 days) non viremic endemic coronaviruses, influenza viruses, parainfluenza viruses, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and SARS-CoV-2. (To date, there are no reports of the latter having been isolated from blood of human COVID-19 cases). The short incubation group are typically initially confined to the mucosal epithelium lumen zone by pre-existing neutralising secretory IgA antibodies, and optimum elevated Innate Immunity involving Interferon Gene Cascade (ISG) activation would likely offer the best immediate mucosal protection as we have discussed at length.

With these issues in mind, we now address the following questions arising from several sets of observations since the 1950s. These need consideration in weighing up the benefit-to-risk of immunological medical interventions. The experiences of the failed public health response during the Covid-19 pandemic are still fresh in our minds. In assessing the vaccination risks these are:

- The genetic uniqueness of every human being.

- The known factors of antigen dose and timing in regulating the class of the immune response – cell mediated immunity (CMI) versus humoral antibody immunity (Ab).

- How the class of the ensuing putative protective or curative immune response (Th1 or Th2) is regulated and can be imprinted on the patient following a vaccination schedule.

- What useful knowledge is possible in advance from neonatal vaccination studies in non-human primates?

The first point directly addresses a central problem of current and previously mandated requirements that random controlled clinical trials be performed on all aspects of any clinical procedure in the population which will be exposed to (any) risk before it is accepted into general practice. Such a requirement needs to be moderated and understood by the reality of the genetic uniqueness of every human being.

1. Genetic uniqueness of every human being

There exists a quantitative genetic measure of the uniqueness of every human being. Twins, apart from their different fingerprints, are genetically different at the somatic level when all pervasive and stochastic somatic genetic mosaicism in all individuals is considered. In addition, monozygotic twins exhibit significant differences in DNA methylation and histone acetylation, which can affect gene expression and function.

McLure et al (2013) estimate, based on random recombinational shuffling and reassortment of ancestral haplotypes at each meiosis, a probability of a repeat genetic complement in human beings of 10400. This is an astronomically large number meaning that no two human beings who have ever existed or are likely to exist in the future have any resemblance of complete genetic identity let alone close identity.

Thus One size does not fit all applies in any potential medical intervention particularly involving manipulation of the highly complex immune system. In our opinion the mandated childhood vaccine schedule violates all basic knowledge and first principles of protective immunity induction. It also violates this principle, as we will see, with standard adult vaccination directed against respiratory diseases such as influenza viruses or coronaviruses. A complete rethink in public health vaccination development, safety testing and efficacy is required, and we are not alone in making this call. As well as Russell and Mestecky (2022) the NIH group of Anthony Fauci now actually admits a rethink is required and necessary following the public health failures in the COVID-19 pandemic. This was well documented earlier for HepB vaccination.

2. Immune Class Regulation – Maturation Th1/Th2 Regulated Class of Immune Response

How is the class of the immune response humoral (or antibody) immunity (usually Th2 regulated) versus cell mediated immunity (CMI) usually Th1 regulated (involving induced curative delayed type hypersensitivity or CD4+ T cells and mature cytotoxic CD8+ T cells) regulated? The pro-inflammatory Th1 immune imprint is induced by low antigen doses early in a response and is a protective and curative response, particularly in the acquired immunity to intracellular infections and early cancer clonal emergence. The Th2 skewed imprint or the anti-inflammatory response (IgG1 response high, Tregs high) appears later as the concentration of a replicating antigen or non-replicating antigen increases (via hyperimmunization). These features depend on the dose of antigen and time during the subsequent immune response and are summarised in the simplified schematic in Figure 1.

Mosmann and Coffman (1989) formally defined the main T helper subsets: CD4+ helper T cells can be divided into two major subgroups based on their production of cytokines. CD4+ Th1 cells produce IL-2 and IFN-γ and mediate delayed hypersensitivity. CD4+ Th2 cells produce IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10 and provide help for B cell Ab responses. The Th1 -> Th2 transition response matures in this direction with time after first antigen exposure, and depending on genetic background and antigen dose, Low through to High (or in hyperimmunization).

3. Immune Class Regulation- The Th1:Th2 transition number, Nt (Figure 1).

The Nt or antigen dose transition number for an individual can be exemplified by the parasitic disease Leishmania major mouse model. It is a very useful principle to employ in environmentally chaotic, genetically diverse human populations, the rule of thumb … the lower the dose of the first immunisation the better the proinflammatory or protective immunity outcome. This cannot be applied in the case of unpredictable endogenous human cancers that have already advanced. However, body of work on lymphocyte collaboration implies possible immune cancer cell manipulations to restart the evolving Th1->Th2 imprint transition. One strategy may involve CD4+ T cell depletions in advanced patients coupled with a challenge with own advanced tumour clones displaying the mature cancer neo-antigens, suitably inactivated as a coupled-protective immunisation step to induce a Th1 imprint in recovering CD4+ cell depleted patients.

Bretscher and coworkers demonstrated this Nt principle for induced immunity to the protozoan Leishmania major in inbred strains of mice. The primary observation was first in BALB/c mice which are susceptible to a standard lethal challenge dose of a million living parasites, in which a rapid anti-parasite Th2 response is generated leading to uncontrolled parasitemia. However prior infection with 100-1000 parasites results in a sustained protective Th1 response whereby such mice resisted the pathogenetic challenge of 106 parasites. They then tested in principle this low dose vaccination strategy in a diverse set of inbred mouse strains. They established that resistance and progressive disease with a stable curative Th1 response or a predominant Th2 response reflective of ongoing Leishmania major parasitic disease. So, the transition number Nt was defined for each inbred mouse strain – the upper limit for that low dose first injection varied over a 100,000 fold dose range for different strains of mice. For slow growing pathogens causing potentially chronic diseases Bretscher and co-workers recommend a low vaccination dose, preferably using living attenuated pathogens, likely to be well below the Nt transition number. In veterinary medicine for domesticated cattle herds, this principle may be easier to apply than in human beings. The principle holds extremely well in that setting and is particularly relevant as it is applied to young calf calves with low dose BCG vaccination against cattle tuberculosis (Mycobacterium bovis).

4. Vaccination Studies in Neonates of Non-Human Primates?

How valuable are the conclusions from vaccination studies in neonates of Non-Human Primates? How relevant to SIDS or downstream developmental maladies that may arise in babies fully exposed to the childhood vaccination schedule? For SIDS the incident rate is ~ 1/170- 1/500 live human births per year depending on each developed country’s National Childhood Vaccine Schedule. However, a simple Google search on such experiments can lead to simplistic and misleading conclusions, when communicated by the mainstream medical media and popular press reports. For example, in a controlled vaccination schedule (MMR vaccine) in newborn Macaques on the incidence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in later development, the authors gave a very misleading conclusion and message. The study by necessity of restricted animal supply of Macaques was conducted in numerically small test and control groups (n ~ 12-15), in a closed colony with a controlled environment. Yet by comparison, in the real world of human existence there is extreme genetic heterogeneity and chaotic uncontrolled environments. Furthermore, the incidence rate for ASD is approximately 1 in 50 to 1 in 100 live births and would require very large study populations thus casting considerable doubt on negative results from small group studies. Yet the institutional media release on the Gadad et al, 2015 study was definitively negative. The study overlooked all these baseline population-wide statistical numbers as well as the reality of life in diverse human populations wherein very large numbers are normally required to establish the real incidence (per 1000 live births) of a condition following neonatal vaccine exposure.

Such a criticism does not negate the value of such findings as newborn Macaques in small groups are potentially useful in assessing mucosal and systemic responses induced by intranasal immunization (and safety issues).

Intranasal booster vaccinations in mice with SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid (N) protein Induction of systemic anti-N Th1 imprints and secretory IgA in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

In the light of the foregoing discussion, we focus on recent interesting findings in mice conducted by Lobaina et al, 2024. It begins to resolve nagging issues raised earlier, namely ….we also need to address whether the same principles of regulation by antigen dose to the initiation of Th1/Th2 responses apply to mucosal immunity and antigens that enter via the oral-nasal route? It needs noting that Bretscher’s latest textbook displays a relative absence of discussion or data for a role for mucosal immunity or mucosal route priming of systemic immunity. Such immunity would be induced by local application of antigen (replicating or non-replicating) to the mucosal epithelium of the nose, mouth and upper respiratory tract, including its impact on the lower gastrointestinal tract. Do the rules and principles developed by Bretscher for the regulation of Th1/Th2 in systemic immunity also hold for the local mucosal applications of vaccine antigens?

Some of Bretscher’s succinct comments on p.148 in his recent 2024 book (The Foundations of Immunology and their Pertinence to Medical Interventions) have prescience and are very relevant. In the light of the public health vaccine failure in the COVID-19 pandemic it is worth quoting him directly in relation to their work on developing Th1 imprinted immunity to tubercle bacilli in mice viz: We found infection of young mice with twenty mycobacteria could generate, in time, the most potent Th1 responses and Th1 imprints. It would be most interesting to see whether such Th1 imprinting can be also generated when immunisation is by mucosal routes, as many pathogens, such as that causing tuberculosis, primarily enter by such routes. The importance of route of sensitisation to the efficacy of protection has been insufficiently explored. Can Th1 imprinting, achieved by parenteral vaccination and tested by parenteral challenge, also protect against a pathogen given by a mucosal route? These are critical questions that have been insufficiently addressed.

Clearly, from the recent experiments by Lobaina et al this appears to be the case. In short, SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid subunit antigen (N, 10 µg) aggregated or not with the oligodeoxynucleotide adjuvant, ODN39M (a 39mer), was delivered by two routes, conventional systemic subcutaneous (s.c) of N with alum as adjuvant or N + ODN39M with alum as adjuvant; or intranasal (i.n) N alone or N + ODN39M, see Figures 1 and 2 in their paper which summarise the main message of their paper.

The data in Lobaina et al fits extremely well with the Th1/Th2 regulation paradigm dependent on Ag dose (a separate study in mice and rats reports Th1 imprints and Th1/Th2 mixed responses consistent with Lobaina et al but not as clean or obvious, in our opinion). It also fits with how the expected natural curative mucosal secretory IgA response and the systemic cell mediated (CMI) response. Th1 imprint is actually set up in nature by immunisation via the Oral-Nasal portal of entry for most inhaled and ingested pathogens bacterial or viral – whether long incubation (10-16 days, thus viremic or septicaemic phase pathogens) or short incubation (2-5 days) pathogens restricted to the mucosal epithelium and lumen of the downstream respiratory and gastrointestinal tract, (Morens et al, see Table 1 for these categories). There are obvious long incubation bacterial and protozoan categories which must also apply such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Bordetella pertussis and Leishmania major.

In Lobaina et al, broadly, with some slight variations, the immunisations were conducted in 6-8-week female BALB/c mice with 10 µg N per mouse on d0, d7, d21 and sacrificed on d33. Lobaina et al measured specific serum IgG, IgG1, IgG2a anti-N antibodies and in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) they measured specific IgA anti-N antibodies; and then in separate time sampling on d12 and d18 they measured in splenic lymphocyte stimulation assays for primed IFN-γ secreting cells by ELISPOT assays, a proxy for the CMI response.

When N+/- ODN34M is given systemically (s.c) with alum adjuvant – there are no mucosal Ab responses (whether IgG, IgG1, IgG2a, or IgA) in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), i.e. no impact on any type of mucosal immunity, an empirical fact evident in many experiments and in our textbooks for over 50 years. However, in serum there is a clear Th2 skewed imprint with the IgG1 to IgG2a ratio very high ~16:1 (and a very low IFN-γ CMI response relative to intranasal route down at least 5 fold). However, if N alone or N+ODN39M is given intranasally there is no serum IgG response of any type and no secretory IgA response evident in the BALF. When N + ODN39M aggregate was given intranasally interesting things happen, – there is a clear serum IgG antibody response but the IgG1: IgG2a ratio is now very low, close to 1. Furthermore, in the BALF IgA antibodies were induced by intranasal route only for the N + ODN39M aggregate.

Clearly, there is a secretory IgA (SIgA) response induced by the intranasal route as well as a Th1 imprint in the spleen. This is the type of result which Bretscher would anticipate if the theory of Th1/Th2 immune class regulation was general for all sensitization routes in the body indeed it exceeds Bretscher’s expectation in his long-sought search for the best way to deliver efficacious protective vaccinations.

This result thus fits a low dose induced Th1 imprint on the parenteral immune system (which is intuitive, in advance, as there is also a physical mucosal barrier to a full systemic 10 µg dose getting into systemic circulation as in the direct s.c. route (with alum) and necessary mucosal secretary IgA in mucosal secretions.

The Lobaina et al discovery re-emphasizes that a properly safety-tested intranasal route with non-alum adjuvants (like ODN39M) should be examined properly and then considered for future vaccinations in all public health programs in both children and adults. However, this particular regimen in mice represents almost adult vaccination and does not parallel infant human vaccination at 2, 4, 6 months which is more likely akin to >12-16 months. These issues must be sorted by extensive research programs which thus requires generously funded research and clinical development programs in all future vaccine development in human beings.

Childhood Vaccine Schedule and development of safe-effective vaccines in infants and adults

We now selectively review recent studies on intranasal versus systemic immunisation in humans and experimental animals in relation to use in a future Childhood Vaccine Schedule and the future development of safe-effective vaccines in infants, children and adults. In advance, the aim is to suggest avoiding schedules that hyper stimulate the neonatal immune system with multiple booster shots of potent adjuvanted (alum-based) systemic doses.

This strong recommendation comes despite one coauthor’s (EJS) active involvement over 35 years ago in the development and refinement of supposed safe alum-based adjuvants. These adjuvants, designed to be pro-inflammatory to initiate lymphocyte and accessory cell collaboration can stimulate potentially harmful systemic levels of circulating cytokines that can have potentially harmful effects on brain health.

The primary focus here needs to be on the induction of mucosal immunity (innate and adaptive) because the great bulk of pathogen infections, in the absence of overt cuts or wounds, initiate via inhalation or via the entry through the eyes and then lacrimal duct drainage to the nasal, oral and gastrointestinal mucosal epithelium.

The mucosal immune system

This is often summarised as the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT). It displays quantitative primacy and dominance in the adult human body. The production of SIgA far exceeds the production of all other Ig isotypes (IgM, IgG subclasses, IgE) in the total adult body, producing about 5-10 grams of SIgA per day, a dominance reflected in the quantitative cellular distribution of lymphocytes and immune accessory cells (dendritic cells and phagocytes). In mucosal tissues they exceed by about two-thirds of all other lymphoid cells (T, B, natural innate killer cells) throughout the body.

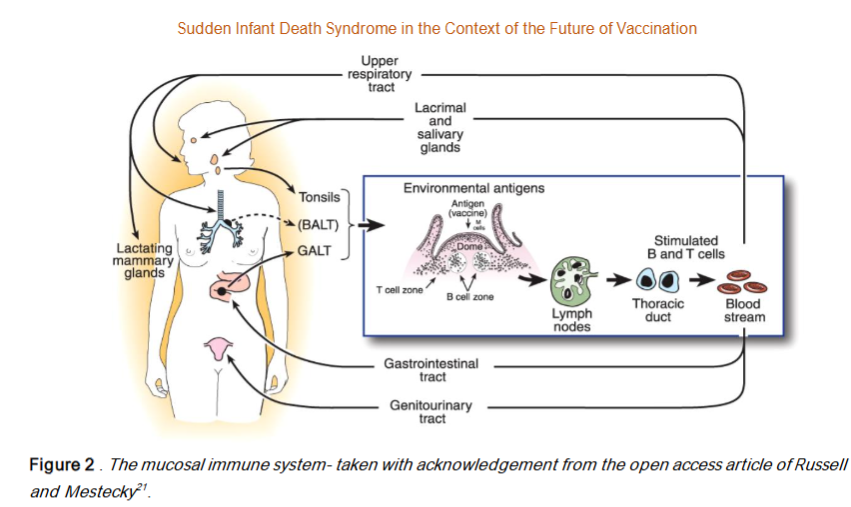

As Mestecky, Russell and other expert colleagues have established since the 1980s the mucosal immune system is not only dominant and physically separate from the systemic immune system it is also functionally separated and interconnected within itself – in an extended common mucosal immune system network generating mucosal tropism of activated B and T cells and activated lymphocyte migration (and recirculation) from (say) the nasal associated lymphoid tissues (NALT) to seed other lymphoid sites in the network viz. the lymphoid tissues of the oral cavity and saliva secretory IgA; the eye-associated mucosa and lacrimal drainage to the nose and mouth; the tonsil and adenoid associated immune system; the mucosal system of other upper respiratory tract and lungs (Bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT); and the lower lung associated mucosal epithelium and the primacy of the gut associated mucosal immune system (GALT) and the numerous Peyer’s Patches lining the gastrointestinal tract; including the MALT of the female and male genitourinary tracts). Russell and Mestecky published an excellent illustration of the mucosal immune system in their Figure 1.

It is indeed surprising to us that this primacy and dominance of mucosal immunity as the first line defence in healthy subjects is so poorly recognised and researched by the dominant mainstream of experimental, clinical and translational immunologists. The mainstream did not understand the so called breakthrough infections or global vaccine failures in prior vaccinated individuals during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. This was a failure to appreciate that systemic immunisation cannot prime and stimulate the mucosal immune system unlike a prior mucosal infection does (e.g the longitudinal population wide study in Denmark in 2020 prior to the mRNA expression vector vaccine rollout).

Indeed, this striking absence of operational knowledge on the primacy of the mucosal immune system prompted mucosal immunology expert Michael Russell to clearly point this public health anomaly out as the prime reason for the public health failure of the systemic vaccination program during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic viz. to partially re-quote Russell, (edited for clarity).

Conclusions The Take Home Message

For all the reasons advanced in this paper we advocate serious consideration of mucosal immune vaccination over the current fashion of systemic vaccination for many common diseases and the childhood vaccination schedule if that is to continue (as a very strong case can now be made for a serious review of efficacy and potential disadvantages to a baby’s health). It appears there is the basic premise that needs to be accepted. We strongly encourage appropriately designed studies in the infant population with inherent parental informed consent. Yet, no randomized control data exists concerning the efficacy and safety of vaccination in infants. The data used to guide decisions come from the easily accessible studies on the adult population. Few it seems advocate for infants, except their parents who adopt the only safe strategy they can use and arbitrarily decide to delay (best strategy) or avoid vaccination altogether.

The exploration of the intranasal mucosal immunization strategy, for all vaccinations, needs to be explored as fast and as thoroughly as possible. The goal is to induce, from the start of the likely infection, the Th1-based Mucosal Immune System rather than the Th2-based Systemic Immune System. The best argument indeed for this approach is that based on an evolutionary perspective – that the primary portal of entry for pathogens throughout human history, apart from overt wounds, cuts and arthropod bites, has been via the nose, the mouth and the eyes. So, a fully funded mucosal immunity research program focused on safe and effective vaccination schedules would seem to be a priority for childhood health and infectious disease research. This aligns with the IPA Congress 2025 Pediatrician Immunization Pledge to which one of us (PNG) has signed.

Such an approach may also reap benefits for teenage and adult vaccination, e.g. the annual Flu shot. Thus, for many years now there has been a search for the universal protective antigenic epitopes common to all known seasonal influenza strains in circulation both found in the past and likely to be a problem in the future. Even if that search for a common protective Flu antigen is successful in the laboratory it will fail in the field if the mucosal route, preferably intranasal application, is not applied. Needless to say, many of our conclusions and recommendations run counter to the ‘one size fits a gold-standard science (sic) approaches pursued with current systemic vaccination against short incubation respiratory pathogens such as SARS-CoV-2.

Acknowledgement

We thank Ben Bornstein for bringing the Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd 8 January 2021, Nonclinical Evaluation Report to the TGA to our attention.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement: None

References

- Fine PEM, Williams TN, Aaby P, Kallander K, Moulton LH, Flanagan KL et al. Epidemiological studies of the non-specific effects of vaccines: I data collection in observational studies. Trop Med Int Health.2009;14:969-976. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02301.x.

- Farrington CP, Firth MJ, Moulton LH, Ravn H, Andersen PK, Evans S et al. Epidemiological studies of the non specific effects of vaccines: II methodological issues in the design and analysis of cohort studies. Trop Med Int Health. 2009;14:977-985. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02302.x

- Goldwater PN, Gorczynski RM, Steele EJ.: Sudden infant death syndrome: a review and re-evaluation of vaccination risks. Medical Research Archives, 2025: 3(3). https://esmed.org/MRA/mra/article/view/6349

- Goldwater PN.: The science (or nonscience) of research into sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Front. Pediatr. 2022;10:865051. DOI:10.3389/fped.2022.865051.

- Miller NZ, Goldman S. :Infant mortality rates regressed against number of vaccine doses routinely given: Is there a biochemical or synergistic toxicity? Hum Exp Toxicol. 2011: 30:1420 1428. DOI: 10.1177/0960327111407644

- Goldman GS, Miller NZ.: Reaffirming a positive correlation between number of vaccine doses and infant mortality rates: a response to critics. Cureus 2023;15(2), e34566. DOI 10.7759/cureus.34566.

- Bretscher P.: What determines the class of immunity an antigen Induces? A foundational question whose rational consideration has been undermined by the information overload. Biology (Basel). 2023a;12:1253. doi: 10.3390/biology12091253.

- Bretscher P.: Rediscovering the Immune System as an Integrated Organ. Freisen Press. Victoria, BC, 2016.ISBN: 978-1-46027406-4.

- Bretscher P.: The Foundations of Immunology and their Pertinence to Medical Interventions. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon , Tyne , UK, 2024. ISBN: 978-1-0364-1257-9

- Lobaina Y, Chen R, Suzarte E, et al.: The nucleocapsid protein of SARS-CoV-2, combined with ODN-39M, Is a potential component for an intranasal bivalent vaccine with broader functionality. Viruses. 2024;16:418. https://doi.org/10.3390/v16030418.

- Mosmann TR, Coffman RL.:TH1 and TH2 cells: different patterns of lymphokine secretion lead to different functional properties. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:145 -173. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.001045.

- Morens DM, Taubenberger JK, Fauci AS.: Rethinking next-generation vaccines for coronaviruses, influenzaviruses, and other respiratory viruses. Cell Host & Microbe. 2023;31:146-157. DOI:10.1016/j.chom.2022.11.016.

- McLure CA, Hinchliffe P, Lester S, et al: Genomic evolution and polymorphism: segmental duplications and haplotypes at 108 regions on 21 chromosomes. Genomics 2013;103: 15-26 DOI:10.1016/j.ygeno.2013.02.011

- Hall NE, Mamrot J, Frampton C, et al. 2020 Blood and saliva-derived exomes from healthy Caucasian subjects do not display overt evidence of somatic mosaicism. Mut Res Fund Mech Mutagen 2020; 821 (2020) 111705 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2020.111705.

- Dou Y, Gold DHD, Luquette LJ, et al.: Detecting somatic mutations in normal cells. Trends Genet. 2018;34:545 557, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2018.04.003.

- Lodato MA, Rodin RE, Bohrson CL, et al.: Aging and neurodegeneration are associated with increased mutations in single human neurons. Science 2018;359:555 559, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao4426.

- Vattathil S, Scheet P.: Extensive hidden genomic mosaicism revealed in normal tissue, Amer. J. Hum. Genet 2016;98;571 578, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.02.003.

- Fraga MF, Ballestar E, Paz MF, et al.: Epigenetic differences arise during the lifetime of monozygotic twins. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:10604-9. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0500398102.

- Steele EJ.: Ancestral Haplotypes. Our genomes have been shaped in the deep past. Nearurban Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9864115-0-2. 2015. https://www.amazon.com.au/Ancestral-Haplotypes-Genomes-Have-Shaped/dp/0986411507. A copy is at https://www.academia.edu/128651012/Steele_EJ_2015_Ancestral_Haplotypes_2nd_Impression_email_ver_copy.

- Russell M. 2022. Review of A single dose of COVID-19 mRNA vaccine induces airway immunity in COVID-19 convalescent patients Qeios (2022), KOTETH. doi: 10.32388/K0TETH.

- Russell MW, Mestecky J.: Mucosal immunity: The missing link in comprehending SARS-CoV-2 infection and transmission. Front Immunol. 2022; 13:957107. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.957107.

- Desombere I, Willems A, Leroux-Roels G.: Response to hepatitis B vaccine: multiple HLA genes are involved. Tissue Antigens. 1998;5:593 604.

- Poland GA, Ovsyannikova IG, Jacobson RM, et al.: Identification of an association between HLA class II alleles and low antibody levels after measles immunization. Vaccine. 2001;20(34):430 438. DOI:10.1016/s0264-410x(01)00346-2.

- Wang C, Tang J, Song W, et al. : HLA and cytokine gene polymorphisms are independently associated with responses to hepatitis B vaccination. Hepatology. 2004;39(4):978 988. DOI:10.1002/hep.20142.

- Frafjord A, Buer L, Hammarstrom C, et al.: The immune landscape of human primary lung tumors is Th2 skewed. Front Immunol. 2021 Nov 18:12:764596.doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.764596. eCollection 2021.DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.764596.

- Corthay A.: How do regulatory T cells work? Scand J Immunol. 2009 :70:326-336. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2009.02308.x. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2009.02308.x.

- Menon JN, Bretscher PA.: Parasite dose determines the Th1/Th2 nature of the response to Leishmania major independently of infection route and strain of host or parasite. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28: 4020-4028. DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199812)28:12<4020::AID-IMMU4020>3.0.CO;2-3

- Bretscher PA.:The problem of host and pathogen genetic variability for developing strategies of universally efficacious vaccination against and personalised immunotherapy of tuberculosis: potential solutions? Int J Mol Sci. 2023b;24:1887. doi: 10.3390/ijms24031887.

- Kiros TG, Power CA, Wei G, et al.: 2010. Immunization of newborn and adult mice with low numbers of BCG leads to Th1 imprints and enhanced protection upon BCG challenge. Immunother. 2010;2: 25-35. DOI: 10.2217/imt.09.80

- Power CA, Wei G, Bretscher, PA.1998. Mycobacterial dose defines the Th1/Th2 nature of the immune response independently of whether immunisation is by intravenous, subcutaneous or intradermal route. Infect Immun. 1998;66: 57.43-5750. DOI:10.1128/IAI.66.12.5743-5750.1998.

- Mamrot J, Balachandran S, Steele E.J, et al.: Molecular model linking Th2 polarized M2 tumour-associated macrophages with deaminase-mediated cancer progression mutation signatures. Scand. J. Immunol. 2019; 89: e12760. DOI:10.1111/sji.12760.

- Jung SW, Jeon JJ, Kim YH, et al: Long-term risk of autoimmune diseases after mRNA-based SARS-CoV2 vaccination in a Korean, nationwide, population-based cohort study. Nat Comm. 2024;15(1):6181. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50656-8.

- Giannotta G, Murrone A, Giannotta N.: COVID-19 mRNA vaccines: the molecular basis of some adverse events. Vaccines. 2023;11(4):747. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11040747.

- Seneff S, Nigh G, Kyriakopoulos AM, et al.: Innate immune suppression by SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccinations: the role of G-quadruplexes, exosomes, and microRNAs. Food Chem Toxicol. 2022 ;164:113008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2022.113008.

- Pfizer Australia 8 January 2021, Nonclinical Evaluation Report BNT162b2 [mRNA] COVID-19 vaccine (COMIRNATYTM), Submission No: PM-2020-05461-1-2 to the Therapeutic Goods Administration, Australian Government, Department of Health, Table 4-2, page 45.

- Burcham P.: An injured toxicologist reflects on COVID mRNA vaccine (Part II). Quadrant.2025 Vol LXIX (No. 616): 26-29 https://quadrant.org.au/magazine/health/an-injured-toxicologist-on-covid-mrna-vaccines-part-ii/

- Bretscher PA, Wei G, Menon H, et al.: 1992. Establishment of stable, cell-mediated immunity that makes susceptible mice resistant to Leishmania major. Science. 1992;257: 539-542. DOI: 10.1126/science.1636090.

- Buddle BM, de Lisle GW, Pfeffer A, et al.: Immunological responses and protection against Mycobacterium bovis in calves vaccinated with a low dose of BCG. Vaccine 1995;13: 1123-1130. DOI: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)00055-r.

- Gadad BS, Li W, Yazdani U, et al.: Administration of thimerosal-containing vaccines to infant rhesus macaques does not result in autism-like behavior or neuropathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:12498-503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500968112.

- Center News. Washington National Primate Research Center 2015 No Evidence of Autism-Like Behavior after Vaccination of Infants- Infant Rhesus Macaques Show Normal Development after Receiving Pediatric Vaccines. https://wanprc.uw.edu/no-evidence-of-autism-like-behavior-after-vaccination-of-infants/.

- Lei H, Hong W, Yang J, et al.: Intranasal delivery of a subunit protein vaccine provides protective immunity against JN.1 and XBB-lineage variants. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):311. doi: 10.1038/s41392-024-02025-6.

- Cooper PD, McComb C, Steele EJ.: The adjuvanticity of Algammulin, a new vaccine adjuvant. Vaccine.1991;9(6):408-445. DOI: 10.1016/0264-410x(91)90127-r.

- Bullmore E. The Inflamed Mind. A radical new approach to depression. Simon & Schuster, London, New York, 2018.

- Pabst R, Russell MW, Brandtzaeg P.: Tissue distribution of lymphocytes and plasma cells and the role of the gut. Trends Immunol. 2008;29:206-208; doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.02.006.

- Mestecky J. The common mucosal immune system and current strategies for induction of immune response in external secretions. J Clin Immunol. 1987;7:265 276. doi: 10.1007/BF00915547.

- Russell MW, Moldoveanu Z, Ogra PL, et al.: Mucosal immunity in COVID-19: A neglected but critical aspect of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Front Immunol. 2020;11:611337. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.611337.

- Brandtzaeg P.: Potential of nasopharynx-associated lymphoid tissue for vaccine responses in the airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011:183:1595-604. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201011-1783OC.

- Gleeson M, Cripps AW.: Development of mucosal immunity in the first year of life and relationship to sudden infant death syndrome. FEMS Immuno Med Microbiol 2004;42 : 21 33. DOI: 10.1016/j.femsim.2004.06.012.

- Subramanian SV, Kumar A. Increases in COVID-19 are unrelated to levels of vaccination across 68 countries and 2947 counties in the United States. Eur. J. Epidemiol 2021;36(12):1237-40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-021-00808-7.

- Hansen CH, Michlmayr D, Gubbels SM, et al : Assessment of protection against reinfection with SARS-CoV-2 among 4 million PCR-tested individuals in Denmark in 2020: A population-level observational study. Lancet 2021;397:1204-1212. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00575-4.

- Martinuzzi E, Benzaquen J, Guerin O, et al.: A single dose of BNT162b2 messenger RNA vaccine induces airway immunity in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 naive and recovered coronavirus disease 2019 subjects. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;75(12):2053-2059.doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac378.

- Kitaura K, Yamashita H, Ayabe H, et al.: Different somatic hypermutation levels among antibody subclasses disclosed by a new Next-Generation Sequencing-Based antibody repertoire analysis. Front Immunol. 2017;8:389. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00389.