Critical Differences in the Treatment of Depressive Symptoms in Narcissistic and Depressive Personalities

Main Article Content

Abstract

In reviewing descriptions of depressive and vulnerably narcissistic personalities, it might appear as if the same condition is being described. The authors briefly review the depressive and narcissistic personality constructs, highlighting the similarities in the two, but also identifying critical differences in how the conditions are manifested. By illustration of two case vignettes and identifying primary symptomatic distinctions, the authors describe the differences in conceptualizing and treating depressive symptoms in depressive and narcissistic personalities. Important distinctions in the roles of perfectionism and living up to idealized expectations are explained, as well as how to understand the role of what appears to be grandiosity. We conclude that while depressive symptoms develop similarly in narcissistic and depressive personalities, the critical distinctions between these organizations outlined in this paper call for divergent treatment approaches. Specially, treatment of depressive symptoms in depressive personalities should involve exploring the client’s disavowed needs and offering appropriate encouragement, while treating narcissistic personalities should focus on the integration of split-off object representations through, in part, challenging their grandiose strivings. Failure to disentangle narcissistic from depressive personalities can lead to counterproductive client internalizations and therefore splitting the categories as we suggest may lead to enhanced clinical utility.

Introduction

Patients with personality disorders and personality pathology often present for treatment because of chronic symptoms of depression. Clinicians often readily identify, assess, and treat these symptoms, though outcomes for such treatment are mixed.1 In part, this can occur because the symptoms of the underlying personality pathology are not identified or targeted for treatment. Or, more problematically, ideas about the origins of this pathology and what are necessary components of treatment for these problems are misidentified or misunderstood. In this paper, we present two case studies of similar patients who present with chronic depressive symptoms. We discuss the management of their depression, but more so focus upon the underlying personality problems to demonstrate the value of differential diagnosis and subsequent treatment planning. We discuss potential pitfalls the clinician might encounter when treating these patients and how to possibly overcome them. Our focus is upon narcissistic personality disorder and upon the historical construct of depressive personality disorder. Both disorders have a rich history in the clinical and empirical literature; both are disorders prone toward chronic depression; and both can be understood as dimensional constructs [pathological narcissism2,3 and malignant self-regard4 respectively] instead of diagnostic categories, which is a diagnostic perspective that is advocated in Section III of DSM-5.5

1. Two Cases Studies1

1.1. Ethan.

Ethan is a 26-year-old Caucasian male who sought treatment because of lingering depression after a break-up with a girlfriend from three years ago. Ethan has a history of

1 These cases are derived from Voytenko and Huprich (in press)

antidepressant usage and psychotherapy. Before entering into his current treatment, he had seen a female therapist, but discontinued treatment after she “shamed” him for how he treated his previous girlfriend. Ethan also devalued the therapist because she was about his age and, in his perception, did not have enough experience to help him.

Ethan indicated that he has been depressed “on and off for years,” even prior to the break-up, thinking he would never get better. He reported some suicidal ideation, but no plan or intent. Most of his problems were attributed to the break-up, a woman whom he believed was perfect for him. Ethan was preoccupied with how his life seemed to have been ruined by this woman. Since then, he has dated intermittently, getting sexually involved with a few women early in the relationship, later deciding they were not good enough for him, did not measure up to his previous girlfriend, or that he was just too “messed up” to be in a relationship right now.

The therapist conceptualized Ethan as having a narcissistic personality that had a moderate level of severity in functioning. Relatively early in the treatment, the therapist identified the patient’s relational pattern as being marked by having an idealized sense of self and devaluation of women; however, this pattern could quickly change when Ethan felt threatened by another person’s abilities or his own guilt, in which he was more devalued and other were more competent or effective. Concomitantly, the therapist observed that Ethan appeared to idealize the therapist and devalue himself, noting how his inner world vacillated between idealization and devaluation.

The therapist utilized a transference-focused approach,6 which seeks to integrate the self and other representations that become split-off and lead to the depressive symptoms and overall dysfunction. For instance, one time, after a brief romantic relationship did not end well, then Ethan smoked marijuana and contacted his former girlfriend. This led him to become very depressed, feeling suicidal, and then smoking too much marijuana and drinking too much alcohol. He also missed work one day. These activities and events led to the therapist gently confronting Ethan about the ways in which he was self-destructive, both to his physical health and his work life. When presented with these issues, however, Ethan avoided discussion of his depressive affect; yet, the therapist would persist and address his resistance, with Ethan eventually talking about the loss he believed he could never overcome. Subsequent interpretations became useful to the patient. He began to find himself feeling more stable and resilient to events that would otherwise be distressing. Over time, he moved more toward a stance of greater curiosity about himself and began feeling less depressed.

Ethan encountered a number of setbacks in his treatment. These involved feelings of loss and a profound sense of vulnerability, usually when a relationship did not go the way he hoped. This included a crisis period lasting a few days after the therapist confronted the patient about coming to session moderately intoxicated. Ethan became very distressed and depressed, fearful of being asked to leave treatment, but also angry that he could not stay there as he was, since there were problems he wanted to discuss. The therapist and Ethan evaluated these events in the next session, with Ethan once again idealizing the work of the therapist in managing the situation as he began to feel better. He also minimized his behaviors by deflecting responsibility. However, the same events were repeated about two months later, this time with greater intensity in depression and substance abuse. Ethan found the experience to be very upsetting, as it led him to recognize how powerfully he medicated himself against his depression and how much his substance abuse hurt him. This led to Ethan sharing with the therapist for the first time a sense of existential distress that was evoked when he broke up with the girlfriend, saying that he struggled to see how life had meaning if he could not be with his “perfect” woman. This allowed the therapist and patient to move into more complex affects that went beyond the break-up that brought him into treatment in the first place.

1.2 Mark. Mark is a 27-year-old professional who entered psychotherapy due to chronic depression that seemed to wax and wane, but yet never went away. He had been in brief, cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy while studying at the university, which appeared to have minimal effectiveness, and was resistant to medication. Mark explained that he has had frequent suicidal ideation over the years, as well as having ambivalent feelings about his current girlfriend and his work.

Mark had many features of what the DSM-4 described as depressive personality disorder, but also qualities of a dimensional construct known as malignant self-regard.4 He was obviously depressed, dysphoric, and prone to periods of unhappiness. However, guilt was his primary affect—guilt about his life experiences negatively affecting others, not performing well at work, and seeking treatment. Not surprisingly, much of his guilt evoke powerful feelings of shame and inadequacy.

Mark also was hypersensitive to feedback from others. For example, at work, after being requested to make some changes to a product in ways he could not have foreseen, he condemned himself. In fact, Mark had strong beliefs about the need to perform at a very high level so as not to be criticized. He believed any mistake might lead to losing his job. Moreover, in his relationship, Mark believed he should comply with what his girlfriend asked, out of fear she might see him as selfish and uncaring. To avoid this, Mark did many things around the apartment to please her. He took pride in how much he did and what he contributed, but yet had fears that he might not be doing enough or that she would find fault in him as a partner because of how depressed he was. Thus, he was reluctant to talk about his sadness with her, thinking he would drive her away.

Early in treatment, the therapist and patient identified ways in which Mark did not recognize and appreciate his agency. He came to understand that stepping away from something unpleasant was not a sign of weakness, but instead an indicator of maintaining his self-esteem and focus on things that mattered to him, not so much to others. However, as the treatment continued, his masochistic attitudes intensified, and he increasingly believed that his problems were entirely of his making. When Mark’s condition worsened, he agreed to consult a psychiatrist for SSRI medications, all of which failed. Mark began to experience dissociative symptoms such as derealization.

As psychotherapy unfolded, Mark changed jobs after putting up with some very damaging conditions for a very long time. However, before that time, a very clear pattern of self and interpersonal relatedness was observed at the workplace. He saw himself as inadequate to manage the stressors that came his way, despite evidence of high effectiveness. Mark wanted to function at such a high level that he could be free of external criticism; yet, as work conditions continued to deteriorate, he drove himself even harder, all the while becoming more depressed and self-critical. Ultimately, he found that he could not adapt to the adversity of the conditions in which he found himself. While the decision to leave was healthy, it was long overdue, and Mark’s departure led him to see this situation as a personal failure. This pattern had clear associations to many events in his childhood and adolescence, in which he tolerated loss after loss, as a result of several family moves, with little attention or awareness of how painful such transitions were for him.

While Mark had spoken favorably about his girlfriend, who seemed to be supportive of him, it became clear as treatment progressed that their relationship was getting strained. As she became more distant, Mark seemed to find greater resiliency and an investment in his own needs, as he seemed to acknowledge the anger he felt toward her for not meeting his needs. In fact, he reported for the first time how much unfounded criticism she had of him throughout the relationship. He reported that she was regularly devaluing him and putting him down, while he masochistically tolerated her demands and expectations all the while being criticized for his depression. In this case, Mark fought for himself, his need for fair treatment and attention, and took a more proactive stance in pointing out the ways his girlfriend was being emotionally insensitive. This led to a reduction in his self-criticism and guilt and more investment in his needs. When they decided it would not work out, Mark was able to accept his disdain for her, given what was now a clear recognition that she had a significant role in the relationship strain.

2. Depressive Personality Disorder/ Malignant Self-Regard and Depression

Malignant self-regard (MSR) is the most recent and comprehensive installment in the lineage of depressive personality. One core aspect of MSR appears in Kernberg’s7-10 conceptualization of the depressive-masochistic personality. Kernberg marked the disorder as having primitive object relations and relying on defenses such as splitting and projective identification; a well-integrated but overly punitive superego; excessive dependency; and depressive proneness (when aggression may have been more appropriate). Similar concepts were observed in two related disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)—masochistic personality disorder (MPD), introduced in the “Other Personality Disorder” section of the DSM-311 (p. 330), and self-defeating personality disorder (SDPD) in the DSM-3-R.12 SDPD replaced MPD due to criticism that the term “masochism,” as understood through a psychoanalytic lens, might blame victims of abuse (especially females in domestically abusive relationships) for their suffering13 (p. 522). However, psychoanalysts, such as McWilliams,14 contend that the term “does not connote a love of pain and suffering” but rather describes a person who endures it “in the hope, conscious or unconscious, of some greater good” (p. 265). Thus, masochism could be viewed not from the vantage point of pleasure derived from pain but from self-sacrifice. Nevertheless, SDPD was subsequently replaced with a somewhat similar diagnostic construct, depressive personality disorder (DPD) in the DSM-4.15 What the depressive-masochistic construct and masochistic, self-defeating, and depressive PDs all have in common is a proneness towards depressive affect, pessimism, shame, an inward expression of aggression, and a cycle of self-defeating behaviors that arise from an unconscious need to suffer as punishment for feelings of guilt10 (p. 21).

Despite displaying satisfactory psychometric properties, clinical utility, and meeting validation criteria for inclusion in the DSM-5, 16,17 the DSM-5 Personality and Personality Disorders Workgroup choose to exclude DPD. Although they gave no official reason (and appeared to violate rules for the exclusion and inclusion of disorders in DSM-5), comorbidity with dysthymic disorders might have been the primary motivation not to include it. 18,19 Still, the overwhelming majority of studies on DPD provide no significant justification for dropping the diagnostic category entirely.17 Consequently, Huprich4 developed a dimensional construct about a self-structure (or representation) that encompasses the shared features of DPD, SDPD, MPD, depressive-masochistic personality, and elements of vulnerable narcissism (which will be elaborated in the following section) called malignant self-regard (MSR20-26). Huprich4 outlined nine primary MSR features as manifested in thought, affect, behavior, and relatedness. They are as follows: depressive proneness, feelings of shame/guilt/inadequacy, excessive self-criticism, hypersensitive self-focus, pessimism, perfectionistic grandiose fantasies, approval-seeking, masochism, and maladaptive anger management.

Analysis of MSR’s factor structure yielded a single latent factor that seems to reflect the internalizing expression of personality pathology, which covers not only MSR but also measures of depression, self-esteem, vulnerable narcissism, SDPD, avoidant, and depressive PD with moderate connections to borderline and dependent PD.21 Overall, these empirical investigations seem to lend credence to the clinically informed description of MSR above. As measured through self-reports, MSR appears to be internally consistent (Cronbach’s alpha between 0.93-0.94,20, 23,27) temporally stable over 2, 4, and 9-week intervals,21 and has evidence supporting its construct validity.20-22

3. Narcissistic Personality Disorder and Depression

Within the past 15 years, narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) has come to be understood via its underlying dimensional construct, pathological narcissism. Pincus and Roche28 introduce two phenotypic subtypes in their hierarchical organization of pathological narcissism: grandiose narcissism and vulnerable narcissism. Grandiose narcissism is colloquial narcissism. That is, it captures the pattern of self-aggrandizing, exploitative, and egotistical behavior people typically ascribe to those they label “narcissists.” 29 This, however, may not be the only manifestation of pathological narcissism. Vulnerable narcissism is a relatively newer conceptualization that describes the emotional vicissitudes that follow from unmet narcissistic needs. Among these are intense feelings of shame, rage, helplessness, worthlessness, and, at worst, suicidality.

Of relevant note, depression is also a major symptom of vulnerable narcissism. Unfortunately, depressive symptomatology is often not the focus of treatment in a number of patients who have vulnerably narcissistic personalities2,3,28 due to the debilitating effects of depression and the frequent life-threatening symptoms associated with vulnerable narcissism.1,23,30 Additionally, vulnerable narcissism’s striking resemblance to MSR is supported empirically.20,21,23,24,27 Specifically, both are associated with low levels of extraversion and self-esteem, high levels of neuroticism, and a proclivity to express anger and anxiety after receiving critical feedback internally.

Consequently, Huprich and colleauges25,26,30 advocated for abandoning the subtype classification within pathological narcissism. Instead, it has been argued that MSR embodies what has been known as vulnerable narcissism, DPD, and SDPD (much akin to Kernberg’s earlier description of depressive-masochistic personality7-10), which then can be meaningfully contrasted against a narcissistic personality defined singularly by the grandiose phenotype. Below we explore several significant differences in the depressive symptomatology of these personalities.

4. Critical Distinctions in Treating Depressive Symptoms in Narcissistic and Depressive Personalities

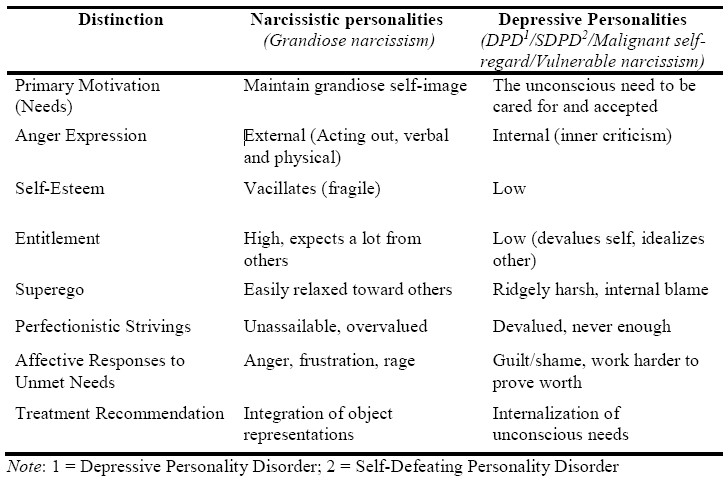

Although narcissistic and depressive personalities share similar features, there are several critical distinctions between them, leading to different treatment recommendations. In Table 1, we identify seven differences in primary motivations, anger expression, self-esteem, entitlement, the punitivity of the superego, perfectionistic strivings, and affective responses to unmet needs20,23 that all lead to alternative treatment recommendations.

4.1 Primary Motivations. Narcissistic personalities (i.e., grandiose narcissism) are defined by the centrality of a grandiose sense of self and are primarily concerned with maintaining that inflated yet fragile sense of self. Underlying the narcissistic personality’s egocentric interpersonal style is a series of grandiose fantasies that enhance the self and accentuate feelings of specialness and greatness, 20 which in turn protects against the crushing recognition of their conventionality or “normality.” To sustain these feelings of grandiosity, the narcissistic personality will overvalue, overestimate, and boast about their abilities to secure the external validation and attention they crave.8

Depressive personalities (i.e., MSR/DPD/SDPD/vulnerable narcissism), on the other hand, are usually compelled to act due to an unconscious or disavowed need for attention, recognition, and care. Early in development, the depressive personalities’ strivings for attention may have gone unrecognized or punished,20 leading to contempt for such needs expressed in the form of aggression directed at the self.31

Often manifested as self-hatred, this initiates an insidious cycle of deeply yearning for others’ attention and acceptance while concurrently rejecting these needs as the depressed personality expects to be disappointed interpersonally.

4.2 Anger Expression. Both narcissistic and depressive personalities tend to express anger problematically. However, narcissistic personalities tend to express their anger externally in verbal or physical outbursts,8 while depressive personalities typically hold anger within through self-criticism.14,20 When faced with recognizing one’s frailty, say in a cutting criticism levied by a loved one, the narcissistic personality may react with a disproportionate retort to harm their perceived attacker. Conversely, the depressive personality may instinctively agree with this insult and invoke other personal faults and weaknesses. Both maladaptive relational patterns stem from their respective primary motivations.

4.3 Self-Esteem. A clear difference between narcissistic and depressive personalities is the stability of their self-esteem. Narcissistic personalities tend to oscillate between feelings of superiority and worthlessness depending on external validation, while the depressive personality’s self-esteem remains consistently low regardless of external validation.8,23 Empirically, the relationship between narcissism (as measured by the Pathological Narcissism Inventory [PNI2,3] and the Narcissistic Personality Inventory [NPI32]) and self-esteem (as measured by the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale [RSES33]) is complex.

Table 1: Critical Distinctions Between Narcissistic and Depressive Personalities

On the one hand, higher levels of (NPI) narcissism tend to be associated positively with self-esteem.34 More specifically, the grandiosity component of narcissism seems to be associated with self-esteem to a larger degree than the vulnerable component.35 Further, Pincus et al.36 found that while the NPI was overall positively associated with self-esteem, the PNI was inconsistently related to self-esteem, reporting many of the subscales capturing vulnerable narcissism (contingent self-esteem, hiding the self, grandiose fantasy, devaluing, and entitlement rage) as negatively associated with self-esteem. These findings suggest that the narcissistic personality’s relationship with self-esteem is contingent on the relative prominence of the disorder's phenotypic expression (grandiose or vulnerable). If one is experiencing feelings of superiority, for example, an elevation in their self-esteem is likely. However, if one is consistently devaluing or hiding the self, a deflation in their self-esteem is expected. These vacillations in self-esteem mark a clear departure from the depressive personality, which is reliably negatively associated with self-esteem.20,23

4.4 Entitlement. Both personalities entail some level of strife in interpersonal relationships based on the severity of the disorder, but the narcissistic personality expects others to meet much higher standards than the depressive personality. One core factor of the narcissistic personality is a sense of entitlement, whether it be an entitlement to the attention, admiration, recognition, or simply the time of others. In this way, the narcissistic personality expects quite a lot out of those who surround them and are, to varying degrees, emotionally contingent on their validation. 8-10 Conversely, the depressive personality has comparatively low expectations of others. They often see others in idealized terms, allowing them to develop and maintain deep and meaningful bonds.20 However, due to their developmental history, expecting the least from others has been a useful strategy,31 even though it often leads to a pattern of devaluing their needs.20

4.5 Punitivity of the Superego. One of the core features of the depressive-masochistic construct (the predecessor of DPD/SDPD/MSR) described by Kernberg7-10 is an overly punitive superego. Depressive personalities are liable to succumb to overwhelming feelings of guilt, shame, and inadequacy expressed concisely in the form of inner-criticism. They readily capitalize on and emphasize situations where self-blame is specious. Even when others are admittedly at fault for an interpersonal disturbance, the rigid urge to rationalize why they are the root of the problem typifies the depressive personality’s relationship to their conscience. Additionally, speaking ill of others is likely to be interpreted as morally objectionable, and therefore the depressive personality is unlikely to criticize others in the way a narcissistic personality might. The narcissistic personality's superego is relatively dormant or pathological,10 allowing them to behave in more overly destructive and vindictive ways. In other words, the depressive personality has a greater capacity for moral functioning than the narcissistic personality.

4.6 Perfectionistic Strivings. Narcissistic and depressive personalities both strive for perfection. However, the fundamental motivation for perfection and their attitudes towards it differ significantly. Narcissistic personalities are motivated to maintain their sense of grandiosity. Perfectionist strivings then are manifestations of a need for their specialness to be externally validated.8 Therefore, their strivings are usually unassailable and overvalued in the hope that others will affirm them.30 For example, a narcissistic personality may inflate their occupational performance and brag to anyone in earshot to prove their greatness.

Conversely, the depressive personality has perfectionistic strivings that are often part of their personality. Despite their typically high accomplishments, they are often unsatisfied with their performance and routinely devalue their work's effort and merit.20 It is never enough, not good enough, or needs more perfecting before they can feel comfortable releasing it to others’ scrutiny. When complimented on their strivings, they may feel uncomfortable and either disregard it or balance it with inconsequential mistakes. Their strivings can also be placed so high that their attainment is virtually impossible, leading to masochistic self-standards that begets pessimism and self-doubt.14 Although having high self-standards is not necessarily pathological, depressive personalities tend to hold themselves to such a high standard that it almost guarantees disappointment and results in disavowed needs for affirmation.

4.7 Affective Responses to Unmet Needs. One of the most apparent differences between depressive and narcissistic personalities are their reactions to unmet needs or disappointments. Given the differences in entitlement, self-esteem, anger expression, and the punitivity of their superegos explained above, it is anticipated that narcissistic personalities will typically react to unmet needs with intense externalized expressions of anger directed at those who disappointed them.7-10 Depressive personalities, on the other hand, are likely to internalize their frustrations as inner criticism.14,20,23,30,31 For example, a patient with a narcissistic personality may berate their therapist for being unable to meet them sooner, while the depressive personality might apologize profusely and feel guilty for even asking in the first place. Both are affectively reactive but different in their expression.

5. Treatment Recommendations

Given these differences in motivation, behavior, affect, thinking, and relatedness, it follows that these personalities should be treated with a clear understanding of their personality dynamics. Very broadly speaking, the treatment goal for narcissistic personalities should be diminishing the grandiose self-representation through establishing a stable sense of self-esteem that allows them to internalize and accept their limitations, weaknesses, and faults, which then can be integrated with their strengths and other positive qualities. In contrast, treatment for the depressive personality should help the patient become aware of and tolerate their unconscious or disavowed desires for care, affirmation, and recognition.30

When treating individuals with a narcissistic personality, it is critical first to understand how the patient’s grandiose fantasies developed. Typically, these fantasies serve as a means of stabilizing the patient’s emotions. For example, a therapist may observe grandiose patterns of the self after a break-up with a romantic partner or after an interpersonal dispute. The therapist can observe this pattern in thinking, and assess how well the pattern is congruous with the patient’s self-representation at that moment. The therapist can then look at the realistic or functional use of this representation in the patient’s life. Consequently, the use of this representation could be associated with a need to protect oneself from upsetting affects and ideas about the other person. From there, the therapist can trace this pattern back into the patient’s relational history to find the origins of how this pattern of self and other representation came into being. One way to accomplish this is through transference-focused psychotherapy,37,38 where the therapist seeks to integrate split-off, self and other representations of grandiosity and vulnerability into a unitary and integrated understanding of one’s identity and knowledge of the other.6 After these patterns have been identified and recognized, the therapist can intervene and challenge them when they occur in the future. For example, pointing out occurrences where the patient begins complementing their abilities (idealizing self) and chastising their coworker (devaluing others) after being criticized by them may serve as an appropriate vehicle for self-observation. Over time, as they become more adept at anticipating and countering their patterns (e.g., idealization/devaluing, needs for external validation, externalizing behavior), the depressive symptoms that arise from splitting objects will diminish, leading to less overall dysfunction and more equitable relationships.

The depressive personality, on the other hand, requires a different approach. When a patient with a depressive personality experiences an accomplishment, it is often met with some ambivalence. For example, an individual graduates from a prestigious four-year institution with a challenging major and a high GPA; their peers subsequently complement them, but instead of accepting the praise with gratitude, they devalue this achievement by insisting on how much help they received, their luck, and their professors' leniency. For the depressive personality, this resistance to positive emotion is often deeply rooted in developmental challenges. For many depressive personalities, their strivings for attention and admiration in childhood often went unrecognized or even punished,20 leading to a disavowal of these needs later in adulthood. However, the need for achievement remains, thus perpetuating an unfulfilling search for recognition and appreciation for their accomplishments. Therefore, a primary treatment aim for depressive personalities should be helping them internalize their accomplishments and the accolades offered by others such that their fundamental self-regard can become more positive and relationships with others more benevolent and satisfying. Throughout the course of therapy, therapists should explore patients’ resistance to achievement of accomplishments, as well as their own self-denigration. Attention should be devoted to the fantasy about what would happen if the patient gave into his or her positive wishes or aspirations, as these will be defended against. In fact, it is possible that the patient might avoid acknowledging these more positive things about him or herself due to a fear of being perceived as arrogant. A consideration of these issues and resistances will likely lead to the resurfacing of childhood experiences in which the child was not recognized or appreciated. With this awareness now afforded to the patient, the therapist can help the patient internalize these more positive aspects of himself by way of observing the praise and accomplishments. Additionally, whenever the client inappropriately devalues the self, it can be met with empathetic challenges from the therapist. Through continual challenges and ongoing working through of more positive internalizations, the patient can become more comfortable with their needs for care and affirmation, feel more optimistic in interpersonal settings, and enjoy some increased level of self-confidence.

Based on these divergences in treatment, the therapist must have an accurate conceptualization of the patient. Given the current subtype model of narcissism (i.e., grandiose vs. vulnerable), some clinicians may erroneously cast a depressive personality as a (vulnerable) narcissistic personality when hearing about achievement strivings and sensing a need for recognition from the patient. The therapist may be focused on what they believe to be pathological grandiosity and be motivated to identify idealized strivings as pathological. A more egregious outcome is that therapists might mistakenly challenge rare self-complements from the depressive personality, virtually guaranteeing increased shame, guilt, inadequacy, and depression in the client. At worst, this can lead to elevated suicidality. Likewise, misidentifying a narcissistic personality as a depressive personality risks exacerbating narcissistic patients’ inflated self-image by offering inappropriate support and admiration while also failing to challenge their inflated strivings and self-assessments. This can encourage and even enlarge the patient’s grandiose fantasies—the opposite of what we recommend for treating the narcissistic personality.

6. Integrating Critical Differences with Case examples

We will conclude by integrating the critical distinctions between narcissistic and depressive personalities delineated in the aforementioned case studies to exemplify how these differences might manifest in clinical practice. In the first case study, Ethan illustrates the narcissistic personality, while in the second, Mark represents the depressive personality.

Ethan’s entitlement revealed itself in at least three manifest ways. First, he felt his previous younger, female therapist was too inexperienced to help him. He felt “shamed” by her when confronted about his behavior in the relationship and believed he deserved a mature and skilled therapist, thus seeking out an older and more experienced professional. Second, Ethan’s previous idealized relationship was used as a standard to compare all other romantic encounters; he felt entitled to a relationship of a similar caliber that resulted in him regarding potential partners not good enough for him, leading to a pattern of devaluing many women in his life. Third, Ethan felt that he had a right to his therapeutic services. For example, after a short crisis period, Ethan came to a session intoxicated. The therapist then ended the session, but instead of respecting the therapist's boundary, Ethan became upset as he felt entitled to his sessions regardless of his state of mind.

Further, Ethan's anger expressions and emotional reactions tended to be externalized in substance use and acting out as expected from a narcissistic personality. For example, in addition to feeling entitled, Ethan felt frustrated and angry with the therapist when he ended the session due to his intoxication, as he wanted to discuss his distress at the moment. Moreover, after the dissolution of a short-lived relationship, Ethan turned to drug abuse, missed a day of work, and then contacted his ex-girlfriend. In the following sessions, these events were discussed, with Ethan praising the therapist's handling of the situation (idealizing) while simultaneously deflecting blame from himself by shirking his behaviors (devaluing), perhaps resulting from a flexible or even disengaged superego.

Although Ethan's self-esteem was typically high, evidenced by his idealized sense of self, it was prone to crumble when he felt threatened or questioned about his skills or abilities. This was a pattern observed by the therapist and confirmed by Ethan when interpretations were presented to him. When dealing with women, Ethan would often idealize himself while devaluing them, including his previous therapist, though with his current male therapist, Ethan consistently idealized him by complementing his accomplishments while devaluing himself. And, at one point during treatment, Ethan decided not to pursue romantic relationships with women he knew because he felt too “messed up” to commit. These inner vacillations of self-esteem characterize Ethan's relationship to his self-worth and exemplify how narcissistic personalities normally relate to themselves.

For narcissistic personalities, perfectionistic strivings or superlative treatment are typically a requirement of both the self and of others. In Ethan's case, the very reason he began therapy was due to a depressive period caused by the loss of a “perfect” girlfriend. His depressive symptoms were supported by the ridged and idealized standard he placed on other women as he desired someone as perfect for him as his previous girlfriend. This went so far as to trigger an existential crisis; Ethan had lost the meaning in his life now that his perfect woman left him. A loss he convinced himself he was unable to overcome.

In line with our treatment recommendations for narcissistic personalities, the therapist attempted to integrate split-off self and other representations that were causing Ethan’s overall dysfunction and depression. As the therapist gently confronted and interpreted Ethan’s self-destructive relational style that mirrored fluctuations between grandiosity and vulnerability, he became less distressed and more curious about himself as he found these interpretations useful. Eventually, these discussions would focus on deeper issues that might have been the root of his narcissistic personality development.

In stark contrast to Ethan's externalizing behavior, Mark's characteristic expression of anger and emotional reactions were often directed inward, at the self. Although chronically depressed, Mark’s primary emotion in times of distress was guilt, which in turn fostered globalized feelings of shame and inadequacy in his work and relationships. Given this hypersensitive self-focus, Mark often internalized criticism as an amplified personal attack. For example, after he was asked to make adjustments to a work project, Mark chastised himself even though he had no way of anticipating the alterations. Any slip-ups were always and only his fault.

Moreover, Mark presented as a competent person; at times, he would even complete his work so efficiently that it would afford him some downtime. Nevertheless, instead of reflecting on his merit and enjoying the break, he would reprimand himself for his perceived laziness. Mark’s perfectionistic strivings were so high that even though they made him highly effective, they were often experienced with a sense of disappointment when his accomplishments really did not lead to the happiness he wanted. His great strivings were never enough in his eyes, leading to guilt and shame, which then required even greater strivings to rectify his deficiencies.

This maladaptive pattern of increasingly self-defeating strivings appeared in his romantic relationships as well. Although feeling positive about the relationship, there was always a nagging fear in the back of his mind that Mark’s depression would lead to its downfall. Mark eventually revealed that his girlfriend had been fairly critical of him and that he would typically behave in such a way as not to elicit her disapproval. However, in his eyes, he was never good enough in this regard. This would only exacerbate the punitivity of his superego in terms of his misbehaviors in the relationship. These strivings seem to be not only due to the rigidity and hyperactivity of Mark’s superego, but to his low sense of entitlement as well. Mark never wanted to hurt anyone and would take extreme measures to alleviate any adverse impact he thought he caused. Over-apologetic, self-sacrificing, and morally masochistic behaviors were regular components of Mark’s behavioral repertoire. He was so fearful of being perceived as selfish or incompetent that he overperformed at his job and often, without resistance, complied with all of his girlfriend's wishes. This did not leave much space for Mark to concern himself with his own needs, especially when they conflicted with others’. Even when Mark finally did leave his job due to worsening conditions, he did not celebrate this as a self-assertive accomplishment but rather blamed himself for not handling the work. All of these factors contributed to Mark’s low self-esteem. Despite his high level of competence at work and pride in his relationship, Mark’s self-esteem remained low. Unlike Ethan, whose self-assessments would at times elevate in concert with his high sense of self, Mark rarely felt these upticks, thus retaining his dysthymic demeanor.

The therapist noted that Mark’s low self-esteem, due in part to his overly critical superego, found its inception in many childhood and adolescent experiences. As Mark was developing, he suffered perpetual losses stemming from changing home and community environments, a series of events that would likely foster depressive, pessimistic, and masochistic tendencies in adulthood. Most importantly, Mark paid little awareness to just how devastating these experiences were for him, reflecting an unconscious disavowal of his pain and needs for care and acceptance. Early in treatment, Mark and the therapist identified ways he neglected his agency following personal and occupational accomplishments and emphasized it when criticized. Intellectually, Mark understood that removing himself from an unpleasant situation was not a sign of weakness but an indication of his self-respect. However, as his distress increased throughout treatment, Mark’s self-defeating behaviors and feelings persisted. At worst, Mark had elevated suicidal ideation and tried various pharmacological treatments in addition to psychotherapy. In turn, Mark’s fears of pushing away his girlfriend were beginning to materialize.

Surprisingly to Mark, however, he found that her growing absence resulted not in increased depression and self-criticism but greater awareness and appreciation of his needs. As his awareness increased, it became clearer how angry he felt not at himself but at her for failing to meet his needs. He also started to understand just how much she criticized and devalued him for his mistakes and depression. After realizing how much he was putting up with, Mark asserted himself in the relationship by drawing attention to how poorly he felt she was treating him. Although they would agree to part ways, Mark eventually accepted his contempt for her, ultimately resulting in less self-criticism, shame, guilt, and overall distress, as well as stronger boundaries around his needs.

Article Details

The Medical Research Archives grants authors the right to publish and reproduce the unrevised contribution in whole or in part at any time and in any form for any scholarly non-commercial purpose with the condition that all publications of the contribution include a full citation to the journal as published by the Medical Research Archives.

References

2. Pincus AL, Lukowitsky MR. Pathological narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6(1):421-446.

3. Pincus AL, Roche MJ, Good EW. Narcissistic personality disorder and pathological narcissism. In: Blaney PH, Krueger RF, Millon T, editors. Oxford Textbook of Psychopathology. New York: Oxford Press; 2013. p.791-813.

4. Huprich SK. Malignant self-regard: A self-structure enhancing the understanding of masochistic, depressive, and vulnerably narcissistic personalities. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2014;22(5):295-305.

5. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

6. Drozek, RP, Unruh BT. Mentalization-based treatment for pathological narcissism. J Pers Disord. 2015;34(Supplement):177-203.

7. Kernberg OF. Severe Personality Disorders: Psychotherapeutic Strategies. New Haven, (CT): Yale University Press; 1984.

8. Kernberg OF. Aggression in personality disorders and perversion. New Haven, (CT): Yale University Press; 1992

9. Kernberg OF. A psychoanalytic theory of personality disorders. In: Clarkin JF, Lenzenweger MF, editors. Major theories of personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1996. p.106–40.

10. Kernberg OF. Aggressivity, narcissism, and self-destructiveness in the psychotherapeutic relationship: New developments in the psychopathology and psychotherapy of severe personality disorders. New Haven (CT): Yale University Press; 2004.

11. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Publishing; 1980.

12. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed., rev. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Publishing; 1987.

13. Millon T, Grossman S, Millon C, Meagher S, Ramnath R. Personality disorders in modern life. 2nd ed. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2004.

14. McWilliams N. Psychoanalytic Diagnosis: Understanding Personality Structure in the Clinical Process. 2nd ed. New York (NY): Guilford Press; 2011.

15. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Publishing; 1994

16. Huprich SK. What should become of depressive personality disorder in the DSM-V? Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2009;17(1):41-59.

17. Huprich SK. Considering the evidence and making the most empirically-informed decision about depressive personality in the DSM-5. Personal Disord. 2012;3(4):470-82.

18. Huprich SK. The overlap between depressive personality disorder and dysthymia, revisited. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2001;9(4):158-68.

19. Ryder AG, Schuller DR, Bagby RM. Depressive personality and dysthymia: Evaluating symptom and syndrome overlap. J Affect Disord. 2006;91(2-3):217–27.

20. Huprich SK, Nelson S. Malignant self-regard: Accounting for common underpinnings among depressive, masochistic/self-defeating, and narcissistic personality disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(4),989-98.

21. Lengu KJ, Evich CD, Nelson SM, Huprich SK. Expanding the utility of the malignant self-regard construct. Psychiatry Res. 2015; 229(3):801–08.

22. Huprich SK, Lengu K, Evich C. Interpersonal problems and their relationship to depression, self-esteem, and malignant self-regard. J Pers Disord. 2016;30(6):742-61.

23. Huprich SK, Nelson S, Sohnleitner A, Lengu K, Shankar S, Rexer KG. Are malignant self-regard and vulnerable narcissism different constructs? J Clin Psychol. 2018;74(9):1556-69.

24. Pedone R, Huprich SK, Nelson SM, Cosenza M, Carcione A, Nicolò G, et al. Expanding the validity of the malignant self-regard construct in an Italian general population sample. Psychiatry Res. Dec 2018;270:688–97.

25. Huprich SK. Malignant self-regard: Finding a place for depressive, masochistic, and vulnerably narcissistic personalities in modern day classification. Persönlichkeitsstörungen: Theorie und Therapie. 2018;22:113-32. Invited paper for special series on masochism, Briken P, Kernberg OF, editors.

26. Huprich SK. Personality-driven depression: The case for malignant self-regard (and depressive personalities). J Clin Psychol. 2019;75(5):834-45. Invited paper for “Complex Depression,” Behn AL, editor.

27. Huprich SK, Macaluso M, Baade L, Zackula R, Jackson J, Kitchens R. Malignant self-regard in clinical outpatient samples. Psychiatry Res. Aug 2018;226:253-61.

28. Pincus AL, Roche MJ. Narcissistic grandiosity and narcissistic vulnerability. In: Campbell WK, Miller JD, editors. Handbook of Narcissism and Narcissistic Personality Disorder: Theoretical Approaches, Empirical Findings, and Treatments. 2011; Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley & Sons Inc, p.31-40.

29. Buss DM, Chiodo LM. Narcissistic Acts in Everyday Life. J Pers. 1991;59(2):179–215.

30. Huprich SK. Commentary: Critical distinctions between vulnerable narcissism and depressive personalities. J Pers Disord. 2020;34(Supplement):207-09.

31. Huprich SK. Depressive personality disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 1998;18(5):477–500.

32. Raskin RN, Hall CS. A narcissistic personality inventory. Psychol Rep. 1979;45(2):590.

33. Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press; 1965

34. Bosson JK, Lakey CE, Campbell WK, Zeigler-Hill V, Jordan CH, Kernis MH. Untangling the links between narcissism and self-esteem: A theoretical and empirical review. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2008;2(3):1415–39.

35. Dickinson KA, Pincus AL. Interpersonal analysis of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. J Pers Disord. 2013;17(3):188–207.

36. Pincus AL, Ansell EB, Pimentel CA, Cain NM, Wright AGC, Levy KN. Initial construction and validation of the Pathological Narcissism Inventory. Psychol Assess. 2009;21(3):365–379.

37. Clarkin JF, Yeomans F, Kernberg OF: Psychotherapy of Borderline Personality. New York, John Wiley and Sons, 1999

38. Clarkin JF, Levy KN, Lenzenweger MF, Kernberg OF. Evaluating three treatments for borderline personality disorder: a multiwave study. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):922-928.